Alex Roddie's Blog, page 8

July 8, 2014

The Heretic by Lucas Bale - book review

The Heretic (Book One of the Beyond the Wall series)by Lucas Bale

This blog tends to have a fairly narrow focus — mountains, 19th century history, books about those subjects, and my own writing — but on special occasions I break the trend and write about something different. This is one of those occasions, and today I'd like to take the opportunity to review the debut novel of an up-and-coming science fiction author, Lucas Bale.

As a child, I was obsessed by science fiction. I devoured the works of Isaac Asimov, Aldous Huxley, Douglas Adams, and many other writers. I think what really attracted me to the genre was the sheer variety and originality of the stories: a kaleidoscope of worlds and characters. In recent years, however, mainstream science fiction seems to have become bogged down in a homogenised Hollywood of trite, predictable plots, packaged in bitesize chunks for the mass market.

I'm happy to report that this book is nothing of the kind.

The Heretic is the first novel in Bale's Beyond the Wall series. The author paints an uncomfortable and frequently bleak vision of a future in which humanity has spread beyond the ruins of an Earth destroyed by climate change and conflict. This is not an original idea, of course, but few ideas are original these days and what counts is how you deal with the idea.

Like all good science fiction, The Heretic focuses on the characters. Bale has chosen to depict only a few characters in his book, but they are masterfully drawn and succeed in paying homage to classic science fiction like Firefly and Star Wars while retaining a distinctive individuality of their own. The freighter captain Shepherd is especially memorable, and his vessel Soteria is very much a character in her own right with numerous surprises up her sleeve.

The Heretic is fast-paced, mysterious, frequently brutal, and like most of the best science fiction poses more questions than it answers. It's all too easy to slap the label "post-apocalyptic" on things these days but I think this book is bigger than that. I have a hunch that we have only been shown a glimpse through the door in this first volume of the series, but the world beyond it is big, frightening, and surprising. At its core is the grand mystery of exactly what happened to Earth and why humanity is now spread so thin.

Lucas Bale’s debut novel is gripping, suspenseful science fiction. It seizes you right from the first word, and the chase scene at the climax of the story is some of the finest writing I’ve seen in the genre — genuinely edge-of-seat stuff.

I look forward to future books in the series, and I suspect this new author will go far!

You can download The Heretic on Kindle from Amazon UK for 99p, or visit the author's website for other links.

Published on July 08, 2014 11:47

July 7, 2014

Aosta to Evolene - an Alpine journey in the footsteps of Professor Forbes

In 1842, Professor James Forbes undertook an epic voyage throughout the Alps. In 2014, I replicated a 40 mile portion of that voyage: the segment between Aosta in Italy and Evolene in the Valais. In this blog post I'd like to tell you about my adventure and what I have learned about the dramatic changes to the ice world in the last 162 years.

For those of you who might not be aware, Forbes is a main character in my Alpine Dawn series (beginning with book 1, The Atholl Expedition ). In real life he was a prolific mountaineer, explorer, and geologist. In his many visits to the Alps he conducted pioneering work on the physics of glaciers and also helped to explore and map the higher regions of the Alps, particularly in the old territory of Savoy.

One reason I wanted to replicate this particular section of the journey was that it crosses the Col Collon, a high glacial pass between Italy and Switzerland. The section in Forbes' book regarding this pass is one of the most memorable; at the time of his crossing he believed he was the first explorer to navigate it, although evidence suggests it had been in frequent use by locals for hundreds of years.

Here's an overview map of my route.

Valpelline

My journey began on the 29th of June in the Italian city of Aosta. I hiked uphill for a few hours to reach the village of Valpelline, my first campsite and the true beginning of my journey. In 1842 Forbes found it to be a tiny settlement with no prospect of accommodation, but managed to secure a room in a friendly household. At that time travellers visited the area extremely rarely and Forbes commented that most of the settlements in the valley were badly afflicted by goitre and cretinism (common afflictions in the high Alps at that time).

The next morning I began the long walk to Prarayer. Most of the route is actually road walking these days but the scenery was so spectacular I hardly minded. The total ascent on my first full day was about 1,200m, and I passed through a number of small villages including Oyace (at a steepening in the valley) and Bionaz. The weather was sunny and very hot, the scenery rather more Italian than quintessentially Alpine.

Typical Val Pelline terrain. The village centre frame is Oyace.At this point mountains of considerable height hugged the valley on both sides, but no glaciers were in evidence and little snow. Forests of larch and pine predominated, and the communities were generally agricultural and deeply traditional. In 1842 Italy as we know it today did not exist; this region belonged to the territory of Piedmont, part of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

Typical Val Pelline terrain. The village centre frame is Oyace.At this point mountains of considerable height hugged the valley on both sides, but no glaciers were in evidence and little snow. Forests of larch and pine predominated, and the communities were generally agricultural and deeply traditional. In 1842 Italy as we know it today did not exist; this region belonged to the territory of Piedmont, part of the Kingdom of Sardinia.Bionaz

Forbes writes:

The village of Biona is the last of any size in the valley,— the last, I think, which has a church. We halted there, and made a hearty meal in the open air upon fresh eggs and good Aostan wine. The village of Biona is 5315 feet above the sea, by M. Studer's observation.Bionaz remains a tiny hamlet clinging to the edge of a precipice, and indeed it hardly seems to have changed in the last 162 years. It had a peculiarity in the 19th century: virtually all of the male inhabitants were also named "Biona," and that was the name of the guide Forbes engaged there to take them over the Col Collon into Switzerland. They nicknamed him l'habit rouge due to his habit of wearing scarlet clothes at all times, which was apparently a common trait in the Pays d'Aoste at that time.

BionazPrarayer

BionazPrarayer

About an hour after Bionaz I reached the reservoir of the Lac des Places de Moulin, the waters of which are held back by an enormous dam. For the first time I gained a view of some of the 4000m mountains, notably Dent d'Herens, which rose as the highest point of a jagged chain above a glacier.

Forbes and his companions stayed at the "Chalets of Prarayon," today a hut known as the Rifugio Prarayer. However, since the formation of the reservoir has obliterated the old road, necessitating a path slightly higher up the hill, I selected a campsite at a flat alp above a larch wood. It had excellent views of the nearby mountains and was a peaceful place to stop for the night.

Camp one. Quite a view!

Camp one. Quite a view!

Alpenglow on the Dent d'Herens and satellite peaksThe Comba d'Oren

Alpenglow on the Dent d'Herens and satellite peaksThe Comba d'Oren

My third day was rather short as I wanted to spend as much time as possible exploring the Comba d'Oren. This is a deep valley leading from Italy to the Col Collon and the border of Switzerland. In 1842 it was reported to be substantially occupied by a glacier:

It was an hour's walk to the commencement of the glacier, which fills the top of the valley, and which descends directly from the great chain. Having gained an eminence on the south-east side of the valley which commanded the glacier, I saw that the ascent of it must be in some places very steep, though, I should think, not wholly impracticable.And:

We there find a deep gorge, completely glacier-bound at its upper end...It's also interesting to note that, although the Comba d' Oren is only a few hours' walk from Valpelline and a day's ride from the city of Aosta (in 19th century terms), the region was almost completely unknown to explorers:

All our maps were here at fault ... no kind of resemblance to the outlines even of the great chain, and the passage must have been put down at random.

The Comba d'OrenToday the Glacier d'Oren, which Forbes and his companions followed to the Col Collon, is dead. Only semi-permanent snow patches remain, and the other two glaciers in the valley have dramatically retreated. I think it very probable that in 1842 there was only one much greater glacier here.

The Comba d'OrenToday the Glacier d'Oren, which Forbes and his companions followed to the Col Collon, is dead. Only semi-permanent snow patches remain, and the other two glaciers in the valley have dramatically retreated. I think it very probable that in 1842 there was only one much greater glacier here.In 2014 the ascent to the Col Collon travels over a variety of scree slopes and small snow fields. It's astonishing to think that in a mere 162 years what was once a large glacier has completely disappeared.

The dead Glacier d'Oren. You can see the stubs of the Glaciers d'Oren Sud (left) and Nord (right) in the background.A night on the glacier

The dead Glacier d'Oren. You can see the stubs of the Glaciers d'Oren Sud (left) and Nord (right) in the background.A night on the glacierI reached the Col Collon (3069m) early in the afternoon and made my camp. The snow was fairly soft so I took my time digging out and consolidating a tent platform. This was actually my first experience of camping on snow with a tent!

Camp Two, beneath the desolate cliffs of La Vierge.It was a wild location. L'Eveque (3716m) towers above, spitting rocks down its central colour every now and again. The Cairngorm-like expanse of Mont Brule (3578m) looked a bit more friendly, and my original plan was to get up before dawn the next morning and make an attempt on that mountain.

Camp Two, beneath the desolate cliffs of La Vierge.It was a wild location. L'Eveque (3716m) towers above, spitting rocks down its central colour every now and again. The Cairngorm-like expanse of Mont Brule (3578m) looked a bit more friendly, and my original plan was to get up before dawn the next morning and make an attempt on that mountain. Mont BruleHowever, the weather soon took a bad turn, and by late afternoon I was starting to wonder if camping on the col had been a wise idea after all.

Mont BruleHowever, the weather soon took a bad turn, and by late afternoon I was starting to wonder if camping on the col had been a wise idea after all. Bad weather coming in from ItalyI made the decision to stay the night. The only reasonable alternative would have been to descend towards Arolla, but with an entire glacier to traverse I didn't fancy my chances of finding a better campsite before dark.

Bad weather coming in from ItalyI made the decision to stay the night. The only reasonable alternative would have been to descend towards Arolla, but with an entire glacier to traverse I didn't fancy my chances of finding a better campsite before dark.A spooky descent of the Haut Glacier d'Arolla

When I woke at 3am, I looked out of the tent and saw that the clag had come in fast, so I went straight back to sleep, not waking again until 7. However, between 3 and 7 quite a lot of snow fell (about 6 inches altogether) and when I awoke the second time my tent was almost buried in it. Visibility had reduced to about twenty feet.

After digging the tent outAlone on a glacier at over 3000m and in dreadful conditions, I knew I had to get out of there pretty quickly! I struck camp in ten minutes flat and began the descent to the Haut Glacier d'Arolla in poor visibility. The fresh snow also made the going treacherous, balling up under my feet, but crampons were necessary due to the patches of bare ice on the slope.

After digging the tent outAlone on a glacier at over 3000m and in dreadful conditions, I knew I had to get out of there pretty quickly! I struck camp in ten minutes flat and began the descent to the Haut Glacier d'Arolla in poor visibility. The fresh snow also made the going treacherous, balling up under my feet, but crampons were necessary due to the patches of bare ice on the slope. A rare view through a break in the cloudFortunately, the Haut Glacier d'Arolla is an easy glacier, relatively flat for the most part and with no real crevasses to worry about. The navigation was no more challenging than a day out in the Cairngorms, and once I focused on my situation and started using the map and compass, the descent proved to be straightforward.

A rare view through a break in the cloudFortunately, the Haut Glacier d'Arolla is an easy glacier, relatively flat for the most part and with no real crevasses to worry about. The navigation was no more challenging than a day out in the Cairngorms, and once I focused on my situation and started using the map and compass, the descent proved to be straightforward. The upper basin

The upper basinIn 1842, Forbes and his companions found the corpses of no less than three people on or near the Col Collon, attesting to its popularity at the time amongst traders and (often) smugglers. The sight of the second skeleton particularly affected the guide Biona, who refused to return that way home by himself after that leg of the voyage:

The effect upon us all was electric ; and had not the sun shone forth in its full glory, and the very wilderness of eternal snow seemed gladdened under the serenity of such a summer's day as is rare at these heights, we should certainly have felt a deeper thrill, arising from the sense of personal danger. As it was, when we had recovered our first surprise ... we turned and surveyed, with a stronger sense of sublimity than before, the desolation by which we were surrounded, and became still more sensible of our isolation from human dwellings, human help, and human sympathy, — our loneliness with nature, and as it were, the more immediate presence of God. Our guide and attendants felt it as deeply as we. At such moments all refinements of sentiment are forgotten, religion or superstition may tinge the reflections of one or another, but, at the bottom, all think and feel alike. We are men, and we stand in the chamber of death.Philosophising aside, the thing that truly struck me was the contemporary description of the Arolla glacier:

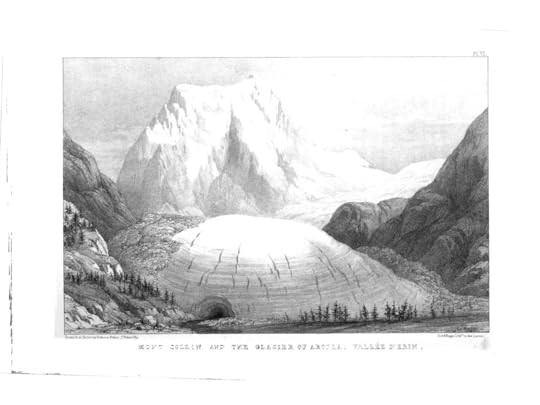

The glacier on which we now were stood is the Glacier of Arolla, that which occupies the head of the western branch of the Valleé d'Erin. It is very long ... The lower extremity is very clean, little fissured, and has from below a most commanding appearance, with the majestic summit of Mont Collon towering up behind.Nowadays the "Glacier of Arolla" is no longer one single stream, but broken into two: "Haut" and "Bas," both of which are rather small by the standards of Alpine glaciers. I calculate that the snout of the upper mass is at least two miles further uphill compared to its location 162 years ago, and moreover, the level of the ice has dropped significantly, leaving vast fields of scree and waste. This illustration from 1842 demonstrates what I mean very well, I think.

The Arolla glacier in 1842. Note the enormous convex snout,

The Arolla glacier in 1842. Note the enormous convex snout,evidence of a glacier until recently in advance; although Forbes noted

that it had already retreated from its recent maximum.

From an almost identical viewpoint today. The upper glacier is out of view

From an almost identical viewpoint today. The upper glacier is out of viewin the left branch of the valley; only the dregs of the lower glacier is still

visible at all, and that is in full retreatIt really is astounding to see direct evidence of glacial retreat on such a scale. The same story is being played out all over the Alps, and it just goes to show what a completely different world it was for the early Alpine explorers. They climbed in a time when the ice was much more extensive than it was today ... and yet even by the 1840s the glaciers were in retreat. The damage was being done two centuries ago.

The ruins of the Bas Glacier d'ArollaEvolene

The ruins of the Bas Glacier d'ArollaEvoleneI reached Arolla fairly early in the afternoon so decided to keep walking. The weather remained misty and rather cold, and I followed the old road through the forest to Les Hauderes, and finally to Evolene, the ancient capital of Val d'Herens.

I first visited Evolene in 2010. It's something of a place of pilgrimage for me. In 1899, Owen Glynne Jones (the main character of my novel The Only Genuine Jones ) stayed at Evolene for an Alpine climbing holiday. He and three of his guides perished on the Dent Blanche during an attempt on the Ferpecle Arete. It was one of the worst climbing accidents of the 1890s and his remains were interred in the cemetery in Evolene, but certain relics, including his hat and ice axe, eventually found their way to the Alpine museum in Zermatt, where they can be viewed today.

Forbes, Studer and co also stayed at Evolene during their voyage. They found it to be an unwelcoming place:

We knew too well what accommodation might be expected even in the capital of a remote Valaisan valley to anticipate any luxuries at Evolena. Indeed, M. Studer had already been there the previous year, and having lodged with the Curé, forewarned me that our accommodation would not be splendid. The Curé, a timid worldly man, gave us no comfort, and exercised no hospitality, evidently regarding our visit as an intrusion.They eventually managed to haggle a single bed, for which the travellers were obliged to draw lots; Forbes won, and poor Studer wouldn't admit where he had been forced to spend the night (probably in a hay barn). He was so traumatised by the experience that he cut his trip short and refused to accompany Forbes any further!

Fortunately my welcome in Evolene was somewhat warmer and I pitched my tent in exactly the same spot I found in 2010, at the campsite in the village. I spent a rest day wandering around the town and making notes — it hasn't changed much since the 19th century, after all — and reflecting on how lucky I had been to repeat this small fragment of Forbes' epic journey, to witness for myself how things had changed in the last 162 years, and enjoy three days of beautiful mountain scenery in the Alps.

Altogether, the route I took was about 40 miles. Strong walkers could easily do it in two days, particularly by taking the bus or driving to Valpelline itself instead of starting from Aosta on foot.

In a future blog post I will write up a trip report of the mountain I climbed from Evolene: Sasseneire, 3254.

Published on July 07, 2014 13:32

June 26, 2014

Three years of work on Alpine Dawn

In summer 2011, I read a book that would change my life.

That book was Travels Through the Alps of Savoy by James Forbes. I've already discussed it many times on this blog, so I won't go into it again now, but it is sufficient to say that it introduced me to a new period of Alpine history and a remarkable character who achieved more over the span of a single summer than most scientists achieve in their entire lives.

In 2011, I was working on The Only Genuine Jones and planning a sequel set in the Zermatt and Evolene area. However, after reading Travels I was seized by a grand new idea and abandoned all plans for a Jones sequel.

Early stages

At first my new project was simply called 1848 and it took me nearly a year to do the preliminary round of research and reading I needed to do in order to get up to speed on the era and the history. By 2012 it had a new name: Alpine Dawn, a phrase taken from the works of James Forbes (who speaks of "standing on the threshold of an Alpine dawn" in 1842, which is remarkably prophetic considering the golden age of Alpinism began not much more than a decade afterwards).

I started working on a first draft in 2012, and by the end of the year I had four chapters written ... but it was hard work, harder by far than anything I had written before. On New Year's Eve I wrote:

Alpine Dawn is not easy to write. It haunts me, challenges me, defies easy classification or comfort. I suspect it has the potential to hold more truth than anything I have written before, but it will have to be wrenched from me, and it won't be ready for a long time.In early 2013 I got bogged down, decided the tone was too bleak and that my main character, Thomas Kingsley, wasn't sympathetic enough. I archived everything I had written and started work on a sideline project which later became The Atholl Expedition.

A bigger picture emerges

I picked up my old Alpine Dawn manuscript and realised that what made the story great was not the details, but the bigger picture. I scrapped the character of Thomas Kingsley, abandoned the dismal Victorian London setting, and focused on my key characters: James Forbes, Albert Smith, and the shadowy legacy of Horace Benedict de Saussure. I wanted to create a grand vision of hope and enlightenment, not financial ruin and despair.

Echoes of my story can be seen everywhere in The Atholl Expedition and it soon occurred to me that this book was, in truth, a prologue to the tale I really wanted to tell. So that decision was easy. The Atholl Expedition became Alpine Dawn Book I. It's a very optimistic novel and it reflects my vision perfectly.

Instead of being hopelessly overwhelmed by a huge plot far too big to be contained in a single novel, I decided to split it into more manageable parts and focus on each at once. The tactic worked. The Atholl Expedition was completed in a timely fashion and published at Christmas 2013.

A Year of Revolution

I am currently working on Book II, which originally had the (rather boring) working title of The Solomon Gordon Papers. I'm now using the title A Year of Revolution instead, which reflects the fact that 1848 is the year everything changes — the tipping point beyond which the actions of my characters begin to have consequences on a European scale.

A Year of Revolution focuses initially on Albert Smith, the London journalist, showman and mountaineer who seeks the answer to the legend of the Pegremont — a mountain of ice discovered by the great explorer Saussure in the 18th century, but lost ever since. The book opens with the June revolution in Paris and Smith finds himself on the barricades, desperate to make his rendezvous with Doctor Barbier of the Hotel Dieu, his old tutor — and an amateur Alpine historian who Smith believes knows the truth behind the Pegremont. He is helped by a savage young woman called Josette who organises the defence against General Cavaignac's National Guard.

It's the beginning of a series of events that will lead to Balmoral, and the hunt for Solomon Gordon's papers — the documents that hold the key that will unlock the mystery of the Alps.

The future

I foresee no end to this series as of yet. After three years of work I have completed one novel, am a good way into a second, and have a third (The Ice World) partially planned. The opportunities for the future are virtually limitless. The Alpine golden age is filled with drama and romance, larger-than-life characters and legends, and it remains an untapped gold mine for the writer of mountain fiction.

People have asked me How many books will there be in the Alpine Dawn series? but the truth is that I simply don't know!

Published on June 26, 2014 03:37

June 14, 2014

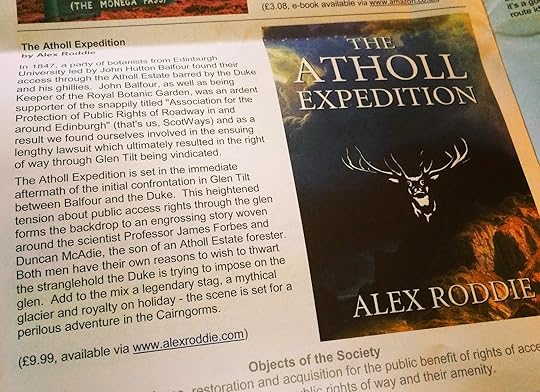

The Atholl Expedition reviewed in ScotWays newsletter

The Scottish Rights of Way and Access Society (ScotWays) is an organisation that fights for public access to the Scottish landscape — not just the mountains, but the lowlands as well. It can trace its origins back to 1845 but one of its first real tests came in 1847 during the infamous Glen Tilt access dispute. A confrontation between Professor Balfour and the Duke of Atholl caused the Duke to declare his game reserve closed to foot traffic. Public access was eventually secured after a lengthy legal battle.

My second novel, The Atholl Expedition, is set in the periphery of this momentous event. The original "Battle of Glen Tilt" is mentioned, and a second similar conflict forms part of the backbone of the story. Professor Balfour makes an appearance as a minor character (and thorn in the side of the dastardly Duke of Atholl!)

I'm very pleased that Scotways has chosen to review Atholl in their latest newsletter, and they have summed up the connection to real events far more succinctly than I ever could! Here is the full text of the review.

In 1847, a party of botanists from Edinburgh University led by John Hutton Balfour found their access through the Atholl Estate barred by the Duke and his ghillies. John Balfour, as well as being Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden, was an ardent supporter of the snappily titled "Association for the Protection of Public Rights of Roadway in and around Edinburgh" (that's us, ScotWays) and as a result we found ourselves involved in the ensuing lengthy lawsuit which ultimately resulted in the right of way through Glen Tilt being vindicated.

The Atholl Expedition is set in the immediate aftermath of the initial confrontation in Glen Tilt between Balfour and the Duke. This heightened tension about public access rights through the glen forms the backdrop to an engrossing story woven around the scientist Professor James Forbes and Duncan McAdie, the son of an Atholl Estate forester. Both men have their own reasons to thwart the stranglehold the Duke is trying to impose on the glen. Add to the mix a legendary stag, a mythical glacier and royalty on holiday — the scene is set for a perilous adventure in the Cairngorms.I would urge all my readers to consider supporting ScotWays. As can be plainly seen, the principles they stand for are key themes in my books, and they do vital work in keeping Scotland's landscape open for all.

Published on June 14, 2014 11:16

June 8, 2014

A return to the Western Alps

My blog has been far too quiet this year, and that's a reflection on the fact that the day job has been occupying more of my time, and (as I recently lamented) I have been able to enjoy fewer trips to the mountains.

However, that is about to change.

Between 2007 and 2010 I visited the Alps three times. It was a natural progression from my mountaineering in Scotland, and my trips (usually accompanied by James) had a focus on getting to the top of big peaks. We had some stunning days out — quite literally high points in my life, the most notable being the moment we stood on the west summit of Lyskamm at 4,479m above sea level.

The ice world is completely unlike anywhere else I've ever been. It's a place of ferocious heat and cold, low oxygen levels, harsh light, and skies a far deeper shade of blue than anything experienced on the surface of the earth. Everything is exaggerated. Timekeeping and a lightweight pack are critical to the preservation of life.

My climbs in the Alps changed my thinking forever and directly spawned the books I continue to work on to this day. Unfortunately, since 2010 I have been unable to return due to work commitments.

I booked a week of holiday at the end of June, and my original plan was to return to the Cairngorms and do a bit of backpacking. However, something made me change my mind and look a bit further afield for my adventure.

The Voyage of Professor Forbes

In 1842, Professor James Forbes (a main character in The Atholl Expedition) conducted a grand voyage throughout the Western Alps. One of the earliest British explorers to turn a critical and scientific eye on the ice world, his achievements that year included laying the foundation of modern glaciology and a pioneering survey that rewrote the map of Savoy (now part of Switzerland, Italy, and France). His writeup of that momentous summer can be read today in the form of Travels Through the Alps of Savoy and Other Parts of the Pennine Chain.

Travels is one of the first pieces of truly engaging British literature from the dawn of the Alpine golden age. Its tone, which reads more like a story than a travel narrative (although it has been compared with an epic poem) was widely imitated by other Alpine classics and echoes of Forbes' voice can be detected in the works of Whymper, Mummery, and Stephen.

I have wanted to follow his grand journey for years, and now I have found the opportunity to replicate a small portion of his route.

My route of choice

On the 29th of June I will fly from Heathrow to Geneva, travel to Aosta, and begin my backpacking route. I plan to walk the length of the Valpelline, cross the Col Collon and descend the Haute Glacier d'Arolla to Arolla itself. My journey will end at Evolene, the ancient capital of the Val d'Herens. The total length is about 40 miles, and I've allowed myself five days to do it, which should permit a leisurely pace with plenty of time to take in the scenery and climb a mountain or two on the way.

This section of Travels Through the Alps is one of the most memorable, in my opinion. When Forbes stood on the Col Collon with his companions he discovered the skeleton of a traveller in the snow. Surrounded by such remote grandeur, he was moved to write a few lines on the awesome nature of the landscape.

"... we turned and surveyed, with a stronger sense of sublimity than before, the desolation by which we were surrounded, and became still more sensible of our isolation from human dwellings, human help, and human sympathy — our loneliness with nature, and, as it were, the more immediate presence of God. At such moments all refinements of sentiment are forgotten; religion or superstition may tinge the reflections of one or another, but, at the bottom, all think and feel alike. We are men, and we stand in the chamber of death."I think this passage reflects the views of a vanishing age in the history of Alpinism. By 1842 the golden age of mountaineering was only a decade away, modern maps were being drawn, travellers were starting to penetrate the deeper valleys, and the Alps would not remain a fearful realm of ghosts and demons for much longer. Today there is a C.A.I hut just beneath the Col Collon and it is a popular route with hikers, but I shall try to see an echo of the old Alps as I follow in the footsteps of James Forbes.

Published on June 08, 2014 09:06

May 28, 2014

The Great Ridge of Edale

I try to balance three driving forces in my life: writing, work (the "day job that pays the bills" kind), and the outdoors. Unfortunately, 2014 has been unbalanced so far, with the day job gobbling up far too much of my time. I've tried my best to keep writing, but my precious moments in the mountains have been severely curtailed. Since my aborted January trip to the Balmoral area I haven't had time to organise another trip to the mountains.

This week my partner Hannah and I decided to head to the Peak District to work on getting the balance right.

Out of all the mountainous areas of the British Isles, the Peak is the one closest to where I live — and yet the one I have visited the least. My only other visit to date was all the way back in 2007, when I attended a navigation course on Kinder Scout with the UEA Fell Club. It was a brief trip but I have fond memories of drinking in the Old Nag's Head (which I tend to think of as the English version of the Clachaig) and challenging compass work on the Kinder plateau.

A snap from the October 2007 tripIt was interesting to revisit Edale after an absence of seven years. I've spent a lot of time in Scotland since then, and the hills don't look as big as they did the first time I was here ... but the point of this trip wasn't to tick off major peaks or do something heroic — it was simply to have a good time in a gorgeous natural setting.

A snap from the October 2007 tripIt was interesting to revisit Edale after an absence of seven years. I've spent a lot of time in Scotland since then, and the hills don't look as big as they did the first time I was here ... but the point of this trip wasn't to tick off major peaks or do something heroic — it was simply to have a good time in a gorgeous natural setting. The Edale camping experienceOn Monday, Hannah and I met up with my brother James, and his girlfriend Nicole, to do a walk over the Great Ridge of Edale. This fine ridge is not quite of the same stature as similarly-named features in Scotland, but the individual summits are beautifully defined and the views are extensive.

The Edale camping experienceOn Monday, Hannah and I met up with my brother James, and his girlfriend Nicole, to do a walk over the Great Ridge of Edale. This fine ridge is not quite of the same stature as similarly-named features in Scotland, but the individual summits are beautifully defined and the views are extensive.We began by walking up the grassy slopes SE of Backtor Farm. This is a lovely walk, made special by its relatively unfrequented nature and the beauty of the scenery both distant and close at hand. We reached the ridge itself after a stroll of about forty five minutes.

Views revealed on the ascent

Views revealed on the ascent The scenic corrie beneath Back TorBeing Bank Holiday Monday, the ridge was packed with walkers, runners, mountain bikers — a mass of people of all kinds. I often find this objectionable on a hill but it seemed somehow appropriate that so many others were up there enjoying the views with us.

The scenic corrie beneath Back TorBeing Bank Holiday Monday, the ridge was packed with walkers, runners, mountain bikers — a mass of people of all kinds. I often find this objectionable on a hill but it seemed somehow appropriate that so many others were up there enjoying the views with us.We nipped up Back Tor for the view from the top before striding the long whaleback form of the ridge towards Mam Tor.

Mam Tor is the highlight of the Great Ridge and has been used as an ancient settlement, hill fort, and more recently as a quarry. We reached the summit easily enough and spent a little while on the summit, taking in the views and watching the paragliders sailing overhead.

On the summit of Mam Tor with three of my favourite people:

On the summit of Mam Tor with three of my favourite people:James Roddie, Nicole Dunn, and Hannah SmeltIt may be a diminutive top by my usual standards, at a mere 517m (less than half the height of some Glencoe summits) but getting to the top of Mam Tor meant something to me. Why? It's the first hill I've climbed this year, and in the drop down to Edale I saw an echo of the wilder, more fearsome summit views I know and love in the Highlands. More importantly, this is actually the first proper hill I've climbed with Hannah, who is a strong walker but doesn't get the opportunity to visit the hills as often as I do. And to enjoy the day with James and Nicole as well was doubly rewarding. We don't get the chance to see them anywhere near as often as I would like.

I've been hillwalking and climbing for a decade now. I've come to realise that the less frequently I get the chance to stand on the summit of a mountain, the more precious each moment becomes.

Getting bogged down on the descent

Getting bogged down on the descent

Journey's end

Journey's end

Published on May 28, 2014 10:46

May 10, 2014

Last Hours on Everest by Graham Hoyland: book review

Last Hours on Everest: The Gripping Story of Mallory & Irvine's Fatal Ascent by Graham Hoyland

It's customary to begin reviews of Everest books with the phrase "Much has been written on this subject." Well, much has indeed been written regarding George Mallory and Mount Everest, but as I hope to demonstrate in this review, I believe Graham Hoyland has a great deal of value to say on the subject — and might even have done more to solve the mystery of George Mallory and Sandy Irvine than any other individual to date.

In 1924, George Mallory and his companion Sandy Irvine perished near the summit of Everest, but nobody has ever been able to establish whether or not the pair actually made it to the top. Graham Hoyland has made it his life's work to find out the truth. He first heard about the mystery from his relative, Howard Somervell, who had been a member of the fateful 1924 expedition. Obsessed by the question since boyhood, he became a mountaineer so that he could climb Everest himself and search for the camera of George Mallory, long believed to be the most reliable piece of evidence that might help to prove or disprove Hoyland's theory that Mallory got to the summit.

The Mallory legend is a romantic one, which helps to explain why it has endured for so long. Mallory was talented, attractive, and had an obsessive relationship with the mountain he both hated and felt compelled to return to again and again. The notion that he may have reached the summit almost thirty years before the first recorded ascent, in 1953 — and with drastically more primitive equipment — is a romantic legend, and it's one that I have wanted to believe for a long time. Everyone seems to have a theory but the truth remains obscure.

Where Last Hours on Everest differs from all the other books on the subject is the fact that the author is a genuine expert on the subject. He has gone far, far beyond most other Mallory researchers, and his expertise — not to mention his obvious passion — helps to bring this story to life more convincingly than ever before.

Graham Hoyland has been to Everest many times, achieved the summit, searched the icy slopes for relics of 1924. The idea of recovering Mallory's body and finding evidence was originally his, and I was interested to read how control of the 1999 expedition was taken from him. Eventually Mallory's body was found by Conrad Anker and, although much valuable evidence was discovered, the way pictures of the corpse were distributed by the media caused considerable pain to Mallory's living relatives. Hoyland, who had planned to handle the matter far more sensitively, was also very upset and the entire episode damaged his reputation.

The author has actually climbed on Everest using exact replicas of the clothing and gear Mallory wore in the 1920s. This is a key piece of evidence, and the book explains how scientific testing (in addition to Hoyland's first hand experience of using the gear) strongly indicated that the gear would have been more than capable of keeping Mallory safe — provided he kept moving. In some respects it's superior to a modern down suit, and the idea that the pioneers wore "lounge suits" or rough tweeds is blown out of the water.

The question of how climbing on Everest has changed over the years is an important theme in this book. The early years of Himalayan exploration are portrayed as intrinsically heroic, but the author chronicles a process of slow change ending in the present era: an age of massive commercial expeditions and the reduction of risk and uncertainty.

The character study of Mallory is relatively brief, but insightful — and does not resort to hero-worship, like some other works. In fact I think Hoyland's ability to be objective and analytical is one of the best things about this book. He portrays Mallory as a talented climber, an intelligent man with a poetic mind, but also shows how he tended to drift through life without much drive or purpose, how he was absent-minded and forgetful, how he took unnecessary risks and put the lives of others in danger. His motivations are probed in detail; like other writers, Hoyland concludes that Mallory's experiences in World War I, coupled with an increasing need to distinguish himself and find something worthwhile to do with his life, contributed to his obsession with Everest.

This book is not just about long-dead climbers and whether or not they were the first to climb the world's highest peak. It's also the story of the author himself and how his life has been shaped by the mystery (and by the mountain). I admired his honesty in discussing how mistakes were made in the search for Mallory's camera, and the recovery of his corpse. It's clear that he was not to blame for the media calamity that followed, but the author is humble enough to acknowledge where he was naive or made mistakes.

The meaning of Everest itself, and climbing in general, is discussed in some depth. No two readers will come to the same conclusion on this but I think the author is more qualified than most to speak about what Everest really means to human beings. He has this to say on the issue of Himalayan tragedies:

"So my answer is, no, Mount Everest is not worth dying for, but I had to risk my life to understand the question."After years of believing that Mallory reached the summit, he describes the legend as "a dangerous and seductive fable" that has indirectly resulted in more deaths on the mountain.

So, did Mallory and Irvine get to the summit of Everest? The answer is that we still don't have enough information. The author evaluates each piece of evidence carefully, placing great importance on some but dismissing others. Ultimately the most important relic — Mallory's camera, which may contain undeveloped film of a summit photo — remains hidden, and until it's found I don't think we will have an answer. As Hoyland says, however, it's very difficult to prove that they didn't reach the summit.

I admire the way the author's views changed from unwavering belief in the Mallory legend to a more more objective point of view. His analysis is sound. He favours simple theories over complex ones, looks critically at the evidence, and is not afraid to change his ideas to fit the science or the facts.

Some reviewers have complained that the book contains "too much Hoyland" and not enough Mallory. I'm afraid I simply don't agree. Mallory's side of the story has been told numerous times by numerous writers, but what makes this book compelling is that it's more than just Mallory-and-Irvine-did-they-or-didn't-they? For me what makes this book stand out is Hoyland's own story, which is full of both triumph and disappointment in equal measure. It's honest and unflinching in describing both.

This is not a book that aims to put Mallory on a pedestal, and it certainly doesn't pretend to have all the answers, but what it does offer is truth, sound reasoning, and a damned good tale told by a confident writer. It's a worthy addition to the canon of books on the subject of Everest and Mallory and I finished the book with a deep sense of respect for Graham Hoyland and his dedication to solving the Everest 1924 mystery.

Last Hours on Everest is available to purchase in hardback, Kindle, or paperback. The paperback edition was launched on the 8th of May. You can purchase a copy from Amazon here.

Full disclosure: I received a review copy of this book from the publisher. However, like all my reviews, it is written independently and without bias.

Published on May 10, 2014 12:37

April 29, 2014

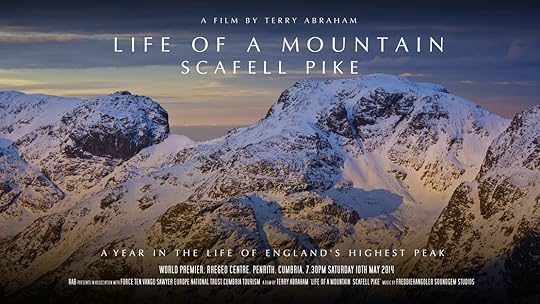

Life of a Mountain - Scafell Pike: film review

LIFE OF A MOUNTAIN — SCAFELL PIKEA film by Terry Abraham

Terry Abraham's mountain films have a certain signature style. Sweeping, panoramic shots of mountain grandeur are accompanied by stirring orchestral music. The pace tends to be slow, contemplative, almost lost in the wonder of the mountains. This formula worked incredibly well in his first film, The Cairngorms in Winter with Chris Townsend, but when I first heard that Terry was creating a longer film about the Lake District I wondered how his style would adapt.

The clue is in the title; or, to be specific, one word of the title: life.

This is a film about more than just one mountain, although Scafell Pike is certainly prominent throughout. It's about the life of Wasdale and the Western Lakes, of the people who work the land and who come to climb the mountains; it's about the inherent life and vivacity of the landscape itself, seen through the eyes of many characters. The theme of life underpins everything in this remarkable film.

The opening titles and cinematography are absolutely spectacular. These cut scenes, each lasting a minute or two and featuring dramatic shots of mountain scenery (frequently sunrises, sunsets, or timelapse shots of cloud spilling over the hills), act as interludes between the main sections of the film but they are in reality so much more. Terry has a unique skill in capturing the true beauty of the mountains and communicating it in a way that makes the viewer feel immersed in the landscape. It's more than just technical skill or artistry, although both are present in abundance; it's about the remarkable lengths he has gone to in order to get some of these shots. After all, he did most of this work alone and unaided.

Like Cairngorms, this film is clearly a labour of love and I am in awe of some of these slow, immersive scenes. I think the timelapse sections shot at night affected me the most, but there's beauty in every section.

Amazing as the landscape interludes are, the meat of the film centres on the human beings (and animals!) who live, work and play around the mountain. A number of characters take the stage. The first is a shepherdess, speaking passionately about the heritage and traditions of the Cumbrian way of life, and this section did a good job of setting the scene for the rest of the film.

The start was slow paced, but it soon gathered momentum. After an ascent of the Piers Ghyll route, we see the summit of Scafell Pike itself about twenty minutes in and I loved the impromptu interviews with happy walkers on the top. Carey Davies from the British Mountaineering Council discussed the ethical consideration of the Three Peaks Challenge and I thought the role of the BMC in protecting the mountains, and our access to them, came across extremely well.

Scafell Pike, viewed from Three Tarns (photo by Alex Roddie)Conservation is an important theme. We see a day in the life of the volunteers who mend paths up the fells, fix drains, and dismantle unnecessary cairns. Nowhere else in England is the impact of humanity on the mountains felt as keenly as Scafell Pike, the highest peak of all, and I think the film does a good job of both explaining the impact itself and how conservation groups are helping to protect the landscape.

Scafell Pike, viewed from Three Tarns (photo by Alex Roddie)Conservation is an important theme. We see a day in the life of the volunteers who mend paths up the fells, fix drains, and dismantle unnecessary cairns. Nowhere else in England is the impact of humanity on the mountains felt as keenly as Scafell Pike, the highest peak of all, and I think the film does a good job of both explaining the impact itself and how conservation groups are helping to protect the landscape.Other characters of note include Joss Naylor, the celebrated fell runner; Mark Gilligan, mountain photographer; Chris Townsend, backpacker and author; and Alan Hinkes, veteran Himalayan mountaineer. Hinkes brings the climbing heritage of Wasdale to life with energy and humour, and even backs off Broad Stand in slimy conditions!

There's so much going on here and the film is really about far more than a single mountain. The pace is brisker than I expected and I learned a huge amount about Wasdale and Scafell Pike that I didn't know before (and I have been visiting the area for years). The overall theme of life and vivacity inspires enthusiasm and fires up the senses.

It isn't perfect, of course. The musical score, while very well judged in most places, is a little sentimental in others. Some of the monologues felt natural and unaffected, while others were more obviously scripted — not necessarily a bad thing, but it broke the sense of immersion a little. I also felt that the film could have been a little shorter without losing any of its substance. However, these are minor quibbles and the overall result is both polished and profound.

I think it's important to remember that this creation was filmed and produced by a team of one. By any standards that's a staggering achievement, doubly so when you consider the scale, charm, and energy of Life of a Mountain. Terry Abraham continues to go from strength to strength and I look forward to his future mountain films.

Life of a Mountain - Scafell Pike premieres on the 10th of May at the Rheged Centre, Cumbria. It is available to pre-order on Stridingedge.com right now and will be released on DVD in mid May.

Next steps

Watch the teaser trailer

Visit Terry Abraham's website

Read my interview with Terry Abraham

Published on April 29, 2014 09:15

April 12, 2014

Returning to places of inspiration

This picture was taken exactly eleven years ago, on Saturday the 12th of April 2003. It's one of my favourite images from my first few years living on the Suffolk coast and also part of my collection of early digital images. In this blog post I'd like to ponder what it means to return to places that have significance for us, and how our own minds influence our perceived reality.

As a family, we first got a digital camera in 2002: a two megapixel beast that ran on 4xAA cells. Despite its woeful limitations by modern standards, this camera had a positive effect on both me and my brother James. Until then we had used traditional film SLRs: capable of taking brilliant photos, but cumbersome, limited, and relatively arcane to operate. James was always much better at the technical side of photography; I was only interested in recording moments in time.

And we recorded many of those moments. In 2002 and 2003 I hiked extensively in the Suffolk sandlings, always accompanied by the digital camera. I took thousands of photos, rapidly filling up the hard drive of our home computer.

It's no coincidence that I look back on 2002 - 2003 as landmark years for both my creativity and my personal development in general.

The link between countryside and creativity

Hiking — or simply being immersed, alone, in nature — has always fuelled my creativity, but in those early years I first consciously identified this phenomenon and learned to harness it.

I walked hundreds of miles through the Suffolk forests, discovering secret places and interesting viewpoints. I followed the coastal defences, sometimes walking 25 miles in a day along the coast. I saw many beautiful sunsets over the marshes. Often walking at night, I found that the thoughts and dreams that bubbled up from my unconscious mind were amplified by the solitude and the silence. During this period, my writing was prolific and I sometimes wrote 30,000 words a week, although I was also unskilled and started more projects than I finished.

The Staverton daffodil field

On the 12th of April 2003 I visited Staverton Thicks, a small wood of ancient oak pollards near Rendlesham. I had walked in Staverton before, but never all the way through to the other side and back through Tunstall Forest. This time I extended my walk.

I found a beautiful view, looking across a slope of daffodils to some birches. I took out my digital camera, recorded the image, and carried on with my walk without giving the scene a second glance.

Somehow, that image — which is a pleasing scene, but objectively nothing special — has taken on a deeper significance for me. That hike was one of many that year, but when I look back over the past decade that day is the one I remember above all others spent outside and alone in the Suffolk countryside. I couldn't tell you why, except that I associate it with all the positive things the outdoors has given me during my life.

But I have returned to that place many times since, and it has never been the same again.

Changing realities

This photo was taken on the 11th of October 2011. On that day I walked the route through Staverton more out of habit than anything else. I was living in Suffolk but my heart was elsewhere. I wanted to move to Lincolnshire and was looking for a job, but the process had dragged out far longer than I had expected and Suffolk was starting to feel like a prison.

I was writing intensively, but I felt at my least creative. I was editing The Only Genuine Jones and made no time for nurturing new ideas. Somehow my daily walks through the forest had lost their ability to inspire me to new creative efforts.

On that day, the daffodil field could not have looked more different. The trees had grown, overshadowing the path and enclosing the meadow on all sides. The sky was thick with rain and the atmosphere was oppressive, silent. No birds sang from the boughs of the ancient oaks.

I looked across the daffodil field and I saw no trace of my moment of inspiration from eight years before.

I wondered why places are never the same when we return. Does the wonder of discovery wear off? Do we walk the same well-worn paths to try and catch that spark we felt at first, only to reduce the power with each subsequent visit?

Perhaps it's significant that I no longer feel this way. When I return to places that have special meaning for me, I now feel the welcome embrace of old friends. When I go back to Great Langdale, or to Glencoe, or to my clearing amongst the birches in Tunstall Forest, I think back to past visits and I feel my batteries recharging. I come back from trips to the mountains brimming with fresh ideas and impatient to start writing something new.

Since those early years of hiking and digital photography I've learned that contrast is actually what feeds my creativity rather than nature alone. Too much of a good thing can dull my senses and take away the magic just as surely as too much time spent at the office.

The landscape changes but little; it is we who change.

Published on April 12, 2014 12:04

April 8, 2014

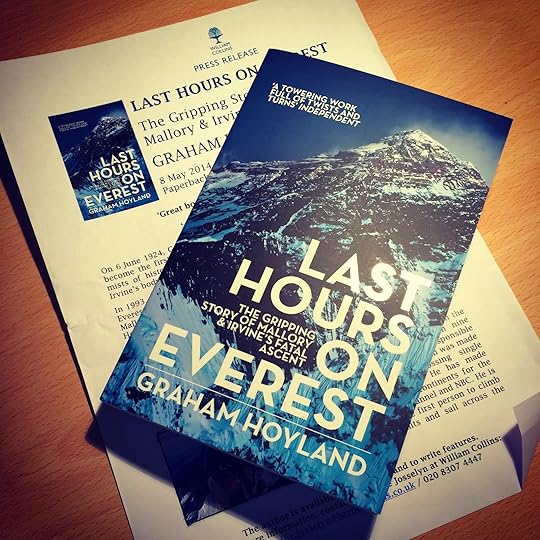

Book Spotlight - Last Hours on Everest by Graham Hoyland

Last Hours on Everest: The Gripping Story of Mallory & Irvine's Fatal Ascent by Graham Hoyland

I came home from work to an eagerly anticipated package today. It contained an advance copy of Graham Hoyland's new book, Last Hours on Everest, which has been available in hardback for a while but will be released as a paperback next month.

Like many recent books, this title concerns the history of Everest — specifically, the final climb of George Mallory. Graham Hoyland aims to reconstruct that final climb and provide the most complete picture yet of what really happened.

At first glance it might be easy to dismiss yet another speculative book about George Mallory and Everest, but what I think will set this one apart is the author's unique insight. Hoyland has climbed on Everest using clothing and equipment almost identical to the gear used by Mallory in the '20s, and he has studied the mystery for many years.

I'm really looking forward to reading this book, which I shall of course review in full on this website when I'm finished!

This title will be released in paperback on the 8th of May 2014. It is currently available to purchase in hardback and Kindle format.

Published on April 08, 2014 11:34

Alex Roddie's Blog

- Alex Roddie's profile

- 27 followers

Alex Roddie isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.