Alex Roddie's Blog, page 6

November 16, 2014

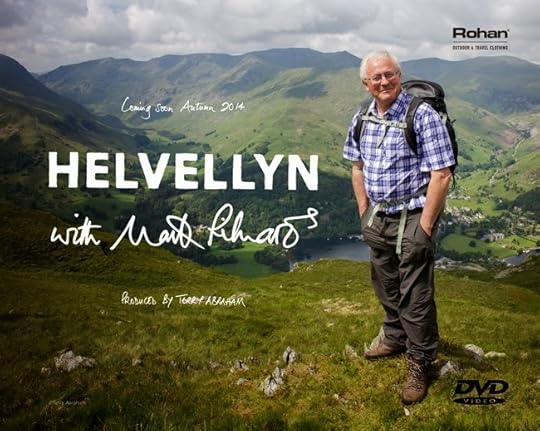

Helvellyn with Mark Richards — film review

HELVELLYN WITH MARK RICHARDS A film by Terry AbrahamWatch the trailer here

Terry Abraham has made his name by creating beautiful mountain films, usually doing all the hard work himself — and that means both the filming and the production. His Cairngorms in Winter with Chris Townsend was a visual feast with long, dramatic cut scenes that immersed the viewer in the spectacle of the winter mountains. I'm glad to say that Helvellyn with Mark Richards is a worthy addition to Terry's repertoire of mountain films, although it is a little different to his two previous titles.

The star of the piece is Lakeland guidebook writer Mark Richards, author of the Lakeland Fellranger series. Mark was a friend of the late Alfred Wainwright, and knows the fells perhaps as intimately as Wainwright did himself. The goal of this short film is simple: to introduce the viewer to the beautiful mountain of Helvellyn, showcasing three very different routes to the summit and talking a little about the human and natural history of the fells along the way. Mark states that he wants to "inspire the viewer to be more appreciative and inventive" in their hillwalking, and in that respect I think the film certainly makes the mark.

The musical scores for Terry's films are particularly distinctive. I'd say the soundtrack for "Helvellyn" is a little more modern, more upbeat, and perhaps a little less sentimental than the scores for his previous two films. It fits the subject matter perfectly and helps to reinforce the idea that this film is a little less heavyweight than his previous titles.

The first route is the east ridge of Nethermost Pike, named "Hard Edge". It's a misty ascent in early autumn and is, I'd say, fairly typical weather for a day out in the Lakeland hills. Mark's commentary on the various features of the route is casual and almost chatty, yet his enthusiasm is palpable — a long way from the dour attitude of Wainwright himself. There are many fascinating details on the etymology of the place names in the surrounding district, many of which stem from Viking words (although Helvellyn itself is more ancient, based on the Welsh language).

Mark Richards illustrates his books with line drawings and I loved how a drawing of a view, occupying the entire screen, would slowly morph into a photograph of the landscape. This was a very visual way of demonstrating how Mark's line drawings aim to interpret the landscape rather than depict it precisely, and I think these scenes add a lot to the film.

The cinematography is up to Terry's usual standards but the mixture of very ordinary weather in the various ascents makes it all a little less grandiose (but no less beautiful). In my opinion this is a good thing. The previous two films were of grander scale and ambition; this is a slightly more humble piece, and as such the cinematography is appropriate. The sweeping cut scenes were as excellent as I thought they would be and the addition of some spectacular drone footage over Striding Edge added an extra dimension.

The second route to be shown was the Brownrigg Well route. In this section Mark was joined by John Manning, editor of Lakeland Magazine. It must be said, some of their banter in the first part seemed a little forced and painful — but things soon settled down and the easygoing, conversational nature of this chapter worked very well in the end. The chief subject of conversation was the geology of the district, but there were also sections about the infamous aeroplane landing on the summit of Helvellyn in 1926 and the various memorials to people who have died on Striding Edge.

I like the way Striding Edge was alluded to — and viewpoints of it teased — before the subject of the famous ridge was directly tackled. Striding Edge is the star of the film's final chapter and, in my opinion, the best part. The views of the ridge are spectacular and a mixture of standard shots, drone footage, and close-up handheld camera work tell the story of the ascent very well. There is also a very interesting interview with personnel from Fix the Fells who are helping to stabilise paths in the area. Mountain conservation is an important theme in Terry's films so it was good to see this aspect addressed so well.

Overall, Helvellyn with Mark Richards is a splendid mountain film. It treads a confident line between the grand and impressive works Terry has produced in the past and the more standard genre of Lakeland hillwalking film we have seen become popular in recent years. Newcomers to the fells will find themselves energised by Mark's enthusiasm, and old hands may learn a thing or two as well — not to mention be enchanted by the beautiful views. Highly recommended.

Buy the film on DVD from Striding Edge here

Further reading

The Cairngorms in Winter with Chris Townsend — film reviewLife of a Mountain: Scafell Pike — film reviewAn interview with Terry Abraham, mountain film-maker

Published on November 16, 2014 06:06

November 15, 2014

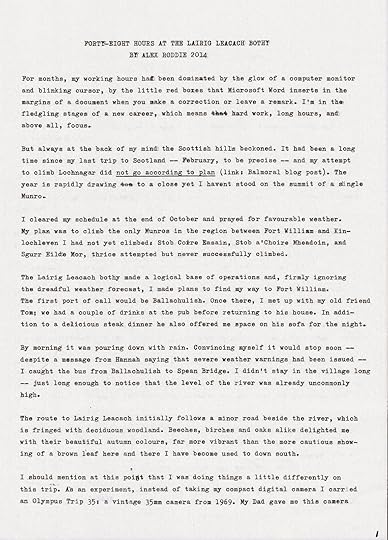

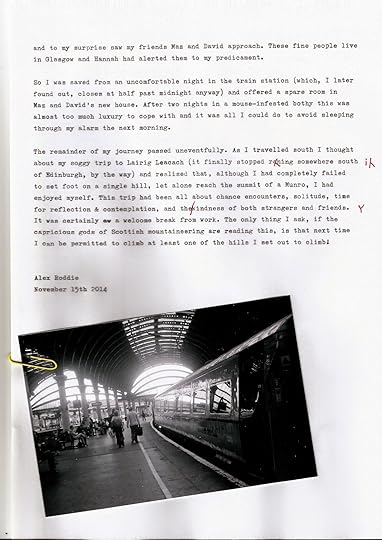

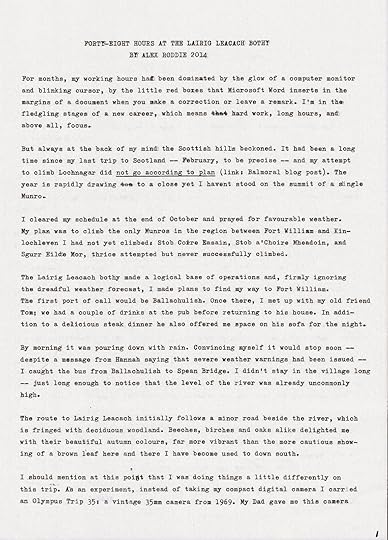

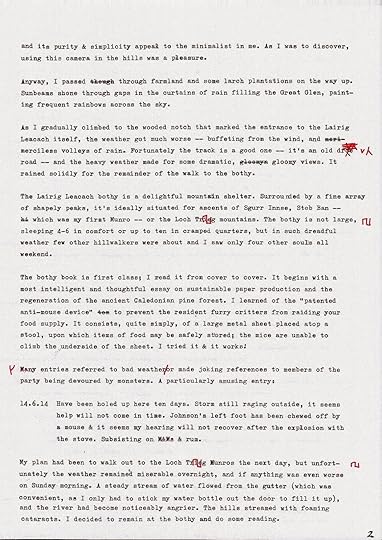

Forty-eight hours at the Lairig Leacach bothy — a typecast

In a departure from my usual form for trip reports, I'm writing this one up as a typecast — that is, scans of pages typed on a manual typewriter. I used an analogue camera to take all the photos on this trip so it feels appropriate. I hope you enjoy this (much-delayed) trip report of a soggy journey to Scotland. Note: you can click on the links below each page to display a full-size version.

Page 1 full sizeLink: Balmoral trip report (January, not February!)

Page 1 full sizeLink: Balmoral trip report (January, not February!)

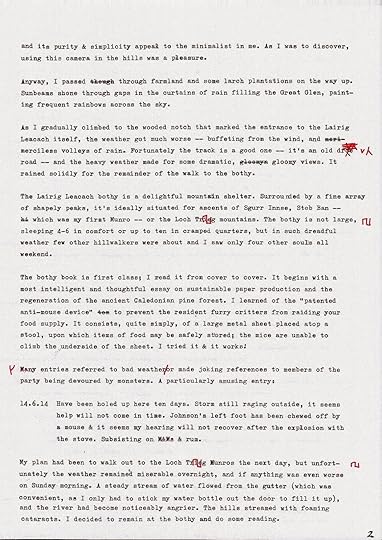

Page 2 full size

Page 2 full size

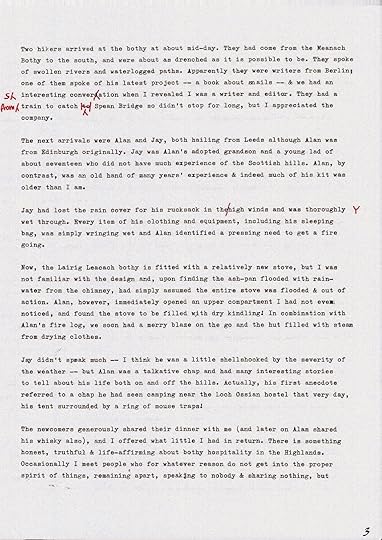

Page 3 full size

Page 3 full size

Page 4 full size

Page 4 full size

Page 5 full size

Page 5 full size

Page 1 full sizeLink: Balmoral trip report (January, not February!)

Page 1 full sizeLink: Balmoral trip report (January, not February!)

Page 2 full size

Page 2 full size

Page 3 full size

Page 3 full size

Page 4 full size

Page 4 full size

Page 5 full size

Page 5 full size

Published on November 15, 2014 04:55

November 10, 2014

Book review and interview: Defiance by Lucas Bale

Earlier in the year I reviewed the debut novel of science fiction writer Lucas Bale. The Heretic plunged the reader into a frightening and chaotic universe. In my original review I wrote:

“The author paints an uncomfortable and frequently bleak vision of a future in which humanity has spread beyond the ruins of an Earth destroyed by climate change and conflict.”Lucas Bale has been busy and has already made the second instalment in the series available for pre-order on Amazon. I was fortunate enough to be invited to read a pre-release version.

You can pre-order Defiance here: Amazon.com or Amazon UK.

The world of Beyond the Wall comes of ageWhile The Heretic was an excellent introduction to the fictional universe of Lucas Bale, Defiance goes deeper. The first volume felt like a prelude to a series of grand scope and in the second we see that series flower and unfold. The pervading sense of danger and chaos is communicated very well and the tone is unrelentingly dark, gritty, and realistic.

This is not an optimistic science fiction future in which all of our problems are solved — if anything, humanity faces more and bigger problems than at any other point in history, with a deeply stratified society causing misery and poverty for millions. There’s a notion that the elite have a conscious plan of allowing the worst of humanity to die out in the name of civilisation. Attempts to terraform planets are sometimes abandoned halfway through, leaving unstable climates and settlements exposed to the ravages of space. Interstellar travel is an arcane art and only vaguely understood.

This sense of realism and detail permeates every page, and the descriptive writing is really rather excellent. The overall result is majestic.

New charactersThe story of Defiance is told from the viewpoints of three new characters. All are complex and driven by a potent cocktail of fears, hopes and neuroses. I found the story arc of Natasha particularly intriguing. A tunnel navigator, she is one of the misunderstood few who can use their senses to feel their way through hyperspace. It’s a novel take on interstallar travel and tunnel navigators are shunned by those around them. Weaver, another primary character, is a Caestor investigating a murder.

Both end up at the dilapidated colony of Jieshou — a forlorn but vividly depicted location. Events later move to an abandoned spaceship and this is the best section of the book, utterly chilling and almost unbearably tense.

Defiance is an excellent book. It’s classic science fiction, written with skill and panache. Good as it is, I think that Lucas Bale is only just getting into his stride, and that the best of this series is still to come.

Interview with Lucas BaleI got in touch with the author to ask him about his work, and he has kindly provided these fascinating insights into his writing.

In The Heretic we catch a glimpse of the world you’re creating in Beyond the Wall, but in Defiance that world unfolds and we see a cruel universe of majestic scale. How do you approach your world-building?

I have always preferred ‘hard science-fiction’. My natural inspiration seems to derive from stories which appear to me to be theoretically possible – they are more compelling to me. Perhaps the simple fact I can relate it to something real makes it more chilling, more believable. The crux of hard science-fiction is the relationship between the accuracy, and amount, of the scientific detail in the story and the rest of the narrative. In 1993, Gary Westfahl suggested that one requirement for hard science-fiction is that a story “should try to be accurate, logical, credible and rigorous in its use of current scientific and technical knowledge about which technology, phenomena, scenarios and situations that are practically and/or theoretically possible.” So, I look to our own world and ask how things might develop if the events which I know have taken place, or are taking place, in the Beyond the Wall series had actually occurred.

When actually world-building, I use two intertwined approaches – macro and micro. When planning the setting for Beyond the Wall, I began with macro. I had an idea for a setting – a time and place, and themes and atmospheres, I wanted to explore. I created a chronology and history, which led to mapping, planet names, ideology, cultural influences, dramatis personae, technology, crime and law enforcement and so on – but these all came from that starting point. I brainstormed from that vision and asked questions – if a given event occurred, what would it lead to? If a character sought a particular outcome, how would they achieve it and what would they need to sacrifice in order to bring about that outcome? How would others react? What is humanity like in my setting? What is important to them, as compared to the issues the world faces now?

Curiously, that meant I moved quite swiftly to micro. I had characters growing in my head and began to ask questions about those characters and how they fit into the general theme of my setting. That process informed me about what the setting required in order to make it sing. Using that new information, I moved back to macro. Political ideology among the characters I was creating, and how that fit into the wider scheme of my setting. Desires and wants and needs – that staple of any character sketching process – has a macro application as much as it does a micro.

The setting for Beyond the Wall is a dystopia centuries into the future and on other worlds as yet unexplored by man in 2014 – but why is it a dystopia? What makes it a dystopia? What makes living in the setting so unpleasant? Why would any system of government allow a dystopia to exist, given the risks of revolution and the cost in maintaining, usually by force, such a system? How, historically, have equivalent political systems operated? What have been their successes and failures, and how have those manifested (and why)?

What does daily life consist of? How do people exist from day to day? Technology, currency, utilities, crime and punishment, transport, a working life — all are issues to be resolved before a setting has muscles over the skeleton. It might be referred to as the infrastructure of the setting. Then you need the flesh and skin – the fine details which make things ultra-real. The way the characters interact with the setting, the changes the setting experiences as the events the characters are players in unfold – all add texture and colour to your creation. Micro and Macro intertwine.

History teaches us about humanity and the way it evolves and history can be a tremendous source of inspiration. For many story reasons, Beyond the Wall mirrors certain elements of the Roman Empire. I have drawn a great deal of inspiration from that period, but so have the characters in Beyond the Wall itself. For reasons which the books will explain, a great deal of my setting draws on historical fact. Twisting it, shaping it differently and interpreting is all part of the challenge of creating an epic setting. But it has to feel ‘real’.

Your viewpoint characters are complex and dark, particularly the navigator Natasha. How did you choose these characters for the story you wanted to tell — or did they choose the story?

A mixture of both. Stories are more compelling if we believe the person telling us that story, and we will only believe them if they are real to us. That means they must be as complex as we are. I have a story I want to tell, but how I tell that story comes from the characters who tell it for me. What they learn (their character arcs) shapes the way in which my themes come across. Also, the story almost always changes as they grow as characters. Lots of authors talk about characters who tell the story for them and are surprised when events in their story change before their eyes because the characters take over. In an epic story, that’s very difficult to permit, but weak characters who act irrationally cannot exist in a good story, so I am forced to listen to them as my story unfolds. Usually, what I thought was a good story arc is far better when the characters tell me where I should be going.

Jordi began life as an intriguing point of view to tell an epic story through, a naive fourteen-year-old from a rural backwater, but who he was going to become was largely a function of me living the story as it unfolded. Natasha came to me as I was walking in Pimlico and saw someone who looked vaguely similar to the way she looks in Defiance; I thought “she’d be fantastic on Jieshou.” With Weaver, I wanted an old, jaded cop, but someone who had voices in the back of his head which inferred a level of entrenched thinking – almost brainwashing – through years of having carte blanche to wield power with impunity. I asked myself, “how would such a man react to given situations?” and also, I wanted him to change his perceptions and attitudes as the story progressed, hence his disillusionment with the Magistratus. Also, I don’t want superhero characters. I want flawed, human characters who have to struggle internally and externally. An epic story is far more compelling if we can identify with the characters as they learn and change. Also, the main theme of Beyond the Wall – what is humanity and what are we permitted to do to protect it – can only come through via “ordinary” people. Of course, in a thrilling space opera, I need to have some reasonably powerful people fighting in these conflicts, but they don’t need to be super-soldiers. Internal conflicts are just as powerful as external ones.

Do you believe that humanity can break free from the shackles of Earth and head for the stars?

I think it’s inevitable. Too many scientific discoveries are being made, or close to being made, currently (LHC, Warp Travel and the Alcubierre Drive, Hypersonic and Scramjet propulsion, and so on); too much enthusiasm exists for space and what lies out there. We are naturally an exploratory species – our history shows us that – I think we’ll eventually realise that we are actually all the same, just a little different in our outlooks and skin colour. The vastness of space may well one day make our international conflicts seem rather petty. Alternatively, we might be forced into heading for the stars if we don’t do something about the problems our own planet faces. It’s a bit of a speculative fiction trope now, but it may well have some basis in reality for our future.

~~~

You can pre-order Defiance here: Amazon.com or Amazon UK.

Postscript: What it Means to Survive

Lucas Bale has just released a short story, also science fiction — and it’s another cracker. Here’s the blurb.

“McArthur’s World is a frozen planet which has been bled dry by mineral mining corporations for three decades. When there is nothing left but ice and snow, the last freighter lifts off carrying away every remaining human being. When it crashes in a wilderness no one has ever returned from, there are only two survivors: a miner who wants to get back to the children he has not seen for two years, and the woman who forced him to come to McArthur’s World in the first place.

“They think they’re alone, until the shrieks in the darkness come.”

Amazon links:

Amazon.com

Amazon.co.uk

Find out moreCheck out the author’s website here. You can follow him on Twitter @balespen.

Published on November 10, 2014 03:05

October 15, 2014

Book review and interview: Low Fidelity by Riccardo Mori

I have published a book review of the serialised science fiction novel Low Fidelity over on my work site, Pinnacle Editorial. It also includes a mini-interview with the author, Riccardo Mori.

There are days in which Internet and what’s happening online dishearten me so much I would like for that to happen — the collapse, I mean. I don’t know whether such a collapse might happen in the real world. In the novel, it happens around 2050, when a lot of different things have reached a saturation point. I believe we’re bound to reach a saturation point in the real world as well. What’s interesting is seeing the real-world outcome of such saturation point, and what it will bring: a fracture? A transformation? A reckoning? Who knows.You can read the rest of the article here. If you enjoy science fiction then I'd highly recommend you subscribe to the author's publication — it's worth every penny!

Published on October 15, 2014 04:29

October 14, 2014

Ditching the Infinity Machine — going smartphone-free in the hills

It seems that outdoor folk have been discussing the use of smartphones in the hills forever, but it’s easy to forget that they have in fact only been around for a few years. In this post I ponder my own use of smartphones in the British mountains and how I’m going to change it.

Mobile phones have been around for as long as I’ve been going into the mountains. I’m in my late twenties. I got my first mobile phone about fifteen years ago and didn’t start venturing into the mountains alone until 2004, so mobile devices in various forms have simply been a fact of life in the hills for as long as I can remember.

However, there is an absolutely fundamental difference between an ordinary mobile phone and a smartphone in the modern sense of the world.

Before the iPhone

Before the iPhone changed the world in 2007, most people used extremely basic mobile phones. They were capable of calling and texting, storing phone numbers, maybe setting alarms and keeping a calendar. Most people didn’t even have camera phones in those days. As I recall, it was actually quite rare to see people using mobile phones in the British hills at all in the first few years of the 21st century, and the popular advice of the time was to keep your mobile switched off in your rucksack in case of emergency.

This was exactly what I did for the first five or six years of my hillwalking career. The mobile phone was, essentially, a single-purpose device — and in the mountains that purpose was to provide a point of contact if something went wrong.

In combination with my mobile phone I carried a PDA (remember those?) in my day to day life. This was for arranging my calendar, contacts and to do lists, but I rarely took it into the mountains unless I wanted to use it as an eBook reader. Between 2008 and 2011 I had an iPod Touch (essentially a glorified Web-capable PDA) which I used as a Kindle on longer backpacking trips, and I can honestly say it revolutionised the way I lived: no longer did I have to consider pack space and weight when considering which books I wanted to take with me. I replaced it with a real Kindle in 2012.

The digital Swiss army knife

I got my first smartphone on contract in 2010.

For a few months, I didn’t do things any differently. My mobile remained switched off in a drybag. I can’t remember exactly when things started to change, but I do know that by November 2010 I had started to use the camera on my phone much more. I’d figured out that a smartphone was lighter and easier to carry than my compact digital camera, and it also provided the opportunity to share photos on Facebook as soon as I got 3G signal.

And the rot set in.

At first I used only the camera function, but soon I began exploring the other possibilities of my device. I discovered Viewranger in 2011: a miraculous app that allowed me to carry detailed, accurate OS maps for any part of the UK on my phone. It had integrated GPS and suddenly navigation was far, far easier than it had ever been. I still carried map and compass, of course, but I didn’t use them much. Eventually Viewranger became my primary navigation tool.

It wasn’t long before I was taking advantage of online weather forecasts, remote access to the UKC climbing logbooks, and even checking blogs when out and about for up to date information on winter conditions. Social media turned mobile and all of a sudden I could post updates from a summit, which was a real novelty. My smartphone also revolutionised travel, allowing me to plan rail and bus journeys, purchase tickets, and track travel disruption from the convenience of a pocket device. I stopped wearing a watch, too.

My smartphone was a digital Swiss army knife. It could do most things reasonably well, and it added a huge amount of convenience to my trips. I convinced myself it was indispensable. It had replaced my watch, my mobile phone, and (to an extent) my map and compass. But there are two glaring problems with using a smartphone in the British hills: signal strength and battery life.

Over-reliance, or simply laziness?

Fast forward to 2013. Last September my smartphone of choice was a Google Nexus 4, and I was halfway through a hillwalking holiday in Glen Shiel. As usual, my smartphone was always on me. It did all my navigating for me. I was posting photos on social media multiple times a day and browsing the Web whenever I could find 3G signal. I tweeted from mountain tops and kept up to date on current affairs from remote glens.

Everything was fine until two problems hit at once: I lost mobile signal in the campsite for a few hours, and my backup battery pack ran out of juice.

The Nexus 4 had terrible battery life. Web browsing on a weak 3G signal could kill the battery in less than two hours, and on my rest day I had found myself mindlessly browsing the Web instead of reading my Kindle. I went to plug the phone into my power brick and found it empty. Surely not, I thought — it usually has enough juice to charge my phone about six times over! But I had somehow been able to drain the 12,000mAh brick in less than four days. I must have been using the phone much more than I had realised.

The Google Nexus 4At the time it was deeply frustrating, and I remember coming back from the trip with a vague sense of dissatisfaction — even though I had to all intents and purposes had a brilliant time and climbed several new Munros. I found it deeply worrying that I could remember hunting for phone signal virtually every day almost as much as I could remember moments of beauty and silence far from the nearest road.

The Google Nexus 4At the time it was deeply frustrating, and I remember coming back from the trip with a vague sense of dissatisfaction — even though I had to all intents and purposes had a brilliant time and climbed several new Munros. I found it deeply worrying that I could remember hunting for phone signal virtually every day almost as much as I could remember moments of beauty and silence far from the nearest road.I thought about it a lot over the following months. Smartphones are so convenient and easy to use that I had gradually slipped into the habit of using mine for everything in the hills, and it had taken over to the extent that the wild no longer felt wild anymore. Losing signal and battery life only served to highlight that point for me.

In July this year, when I went to the Alps, I also took my phone with me (this time an iPhone with dramatically better battery life). Signal strength was never a problem and I moderated my usage a little more, so there were no issues with battery life this time — but I still found myself posting to Twitter and Instagram when I had the chance. And I didn’t really know whether or not that was a good thing for me. I enjoyed the feeling of being in touch and able to chronicle my voyage in real time, but somewhere at the back of my mind was the nagging feeling that things had changed, and that being constantly connected was affecting my relationship with the outdoors.

Change

Since my change of career I have found myself in an environment where the rapid pace of technological development is no longer a factor in my life. I am no longer surrounded by people whose job is to sell the latest and greatest to everyone who walks through the door, and I no longer keep up to date with all the latest tech blogs (which I used to do, because it was part of my job). I find myself re-assessing the role of technology in my life, and in many respects I find myself reverting to the habits and conventions I had before 2011.

I have slowly come to realise that, convenient as a smartphone is for mountain use, it’s not at all as necessary as I once thought it was — and it may actually be damaging my enjoyment of the hills.

Where I had once planned ahead, I now simply open an app and it plans journeys for me. Where once I had kept a detailed journal, now I Tweet and Instagram in the hope of instant validation from my followers — and these posts will soon be lost in the aether and never read by anyone again. Where once I had relished the challenge of navigating by map and compass, now I simply look at my screen and it tells me where to go. Where once I had been self-reliant enough to study the sky and the snowpack for signs of what conditions would be like, now I would simply load MWIS and SAIS on my phone. It has all become a little too easy for comfort.

And when the signal or the battery goes dead, I find myself suddenly plunged back into a disconnected, uncertain world that I have gradually drifted away from over the years.

This decision has been a long time coming, but I have come to the conclusion that I need to stop taking my smartphone into the mountains. I miss the feeling of stepping off the grid that I once enjoyed. For all a smartphone’s talents it isn’t as good as a map for navigation, it isn’t as good as a real camera for photography, and the humming connectedness of the Web is no substitute for being alone in nature, accompanied by my thoughts. Ideas come to me when I’m on my own so this is a big deal for me. If I never have time and space to think for days on end, where are the ideas for future stories going to come from?

What I’m going to do

My strategy is obvious: I’m going to buy a basic phone, stick a pay as you go SIM card into it, and use that instead. It will remain switched off in my rucksack unless I need to use it. Simple.

I’m also going to start wearing a watch again.

My Kindle will continue to come with me for reading material (you’ll pry that from my cold, dead fingers!) but I will stop relying on a machine to do my thinking for me. Smartphones aren’t that reliable in winter conditions anyway.

Now, before anyone jumps to the conclusion that I’m telling everyone they should go back to a basic mobile, I must stress that this is only my experience. I also completely get that some people need constant connection at all times for their jobs, but I am fortunate enough not to need that now. If I’m going away for a week, I’ll tell my clients before I go. I’m my own boss so I have that luxury.

I’d be interested in hearing the views of my readers. Do you take a smartphone into the hills, and how has your approach changed over time? Do you use it just for calls, texts and maybe getting weather forecasts, or do you use it as a navigation and social media tool as well?

Further reading

Thought processing: analogue vs. digital

How to turn an Android phone into a dedicated GPS device

Published on October 14, 2014 04:19

October 7, 2014

The gift of impermanent permanence

In early 2002 the Roddie family moved to a small village on the Suffolk coast. At the time I was sixteen years old and I didn't appreciate the move. I felt that I was being taken away from my friends, and I didn't really apply myself to making new ones during my two year stint at Sixth Form College.

At first I merely saw Suffolk as a stop-off point before University and freedom. But in summer 2002 something changed.

On the 1st of August that year I went on a hike through the forest. Sudbourne is surrounded by woodland on three sides, cut off from the rest of the world, but until that point I hadn't really ventured into the forest by myself. I planned a ten mile route from our house in Sudbourne to Blaxhall Heath and back. The walk wasn't anything special in the grand scheme of things — although according to my journal I saw a wild boar — but it had the effect of unlocking something in my mind. I found it astonishing that I had been able to walk ten miles without setting foot outside Tunstall Forest. It occurred to me that on my doorstep awaited a magical land ready for exploration and adventure.

Thus began a period of personal growth. I had always been introverted, quiet, and imaginative. While many young people in their late teens are discovering loud music and girls, I started a process of outdoor awakening that would eventually lead to my passion for mountaineering. (The loud music and the girls came in due course, a few years later.)

Memorable days and nights in the Suffolk Sandlings

The coastline, forests and heaths of the Sandlings form a unique landscape. Its beauty is obvious but its wildness is extremely subtle. There are no mountains here, no vast stretches of pristine wildwood or empty glens. The forests of Tunstall and Rendlesham are owned by the Forestry Commission, and largely consist of managed conifer plantation, thinned and felled on a rotation basis. The scraps of wilder forest that fill the gaps are vanishingly small. A larger collar of untamed birch woodland surrounded my home village of Sudbourne, and it was in "The Birches" that I spent many afternoons, building dens amongst the trees or fashioning stone age weaponry. This is where I developed my love of bushcraft that continues to this day (although nowadays my tool of choice is an Opinel or Mora knife rather than something fashioned out of flint!)

Even amongst the ordered rows of Sitka Spruce, planted for paper, I found many surprising fragments of wildness.

Beautiful trees are hidden in these woods. Many of them became significant landmarks, and I even gave a few of the grandest trees names. An ancient oak stands at the border of the forest, and I named him the Goblin Oak many years ago for reasons I have now forgotten.

The Goblin Oak in winter

The Goblin Oak in winter

... and in JuneI came to understand and appreciate the turning of the seasons, how the rhythm of sunlight and time turns the lime green of June into the burnt shades of August and finally the mellow, bountiful golds that begin to show in October. I learned the secret routes away from the main thoroughfares and discovered hollowed clearings far from any path where I would bivouac for the night with the warmth of an open fire for company.

... and in JuneI came to understand and appreciate the turning of the seasons, how the rhythm of sunlight and time turns the lime green of June into the burnt shades of August and finally the mellow, bountiful golds that begin to show in October. I learned the secret routes away from the main thoroughfares and discovered hollowed clearings far from any path where I would bivouac for the night with the warmth of an open fire for company. The author playing with fire

The author playing with fire

An impromptu bivouac in June 2006It was a time of deep thought and observation. I went walking and bivouacking most weekends, and I spent the remainder of my free time writing.

An impromptu bivouac in June 2006It was a time of deep thought and observation. I went walking and bivouacking most weekends, and I spent the remainder of my free time writing.Away from the forests themselves, I planned huge stomps around the coastline. The estuaries are guarded by riverwalls that generally carry public footpaths, so it's possible to walk any distance you like along the coast. My favourite route became known as the Orford Coastal Route and I must have walked it well over a hundred times, but others (the South Coastal Route and the North Coastal Route) I trod more rarely due to the starting or ending points being far from my house.

Most of my big walks were conducted in 2003. My longest one clocked in at about 28 miles. I often thought about a big link-up of several of the coastal paths strung together over a long weekend, but never quite got round to doing it.

One of my favourite views: the estuary at Iken. This shot was taken

One of my favourite views: the estuary at Iken. This shot was takenin 2004.I move away

This period came to an end in 2005. By that point I had discovered hillwalking and backpacking, both of which were a direct continuation of my lowland ramblings. My first Lakeland backpacking trip in May 2005 changed my perspective and, when I returned, the Sandlings just weren't the same anymore. I had started to get restless.

I started my three year course at UEA in September, and my focus changed firmly to mountains and mountaineering.

The gift of impermanent permanence

The Sandlings remained an anchor in the rapidly changing ebb and flow of life. I returned infrequently — at first during holidays between semesters, and later, after I moved to Scotland, I made the journey South several times a year to visit my parents and tread the old paths again.

When one sees a place every day for a year, change often gets overlooked. The Goblin Oak might have been a little fatter, a little hoarier, but I didn't notice because the change had been gradual.

But I was surprised at the changes both large and subtle that I noticed after long absences from the places I knew so well.

Trees lurched upwards. Entire plantations grew from thickets of saplings to swaying cathedrals of pinewood and dappled shadow — only to be felled and gone on my next visit, reduced to a field of stumps and encroaching bracken. I saw trees grow, fall in an October storm, then wither and decay to a mossy bump in the ground. The forest hut I built in 2002 was a wreck by 2006 and was completely absorbed by 2010.

I became fascinated by the morphing, pulsing life of the forest and how it was at once a permanent feature in my life and yet every time I visited I saw more change occurring all around me. On one level it was a great balm for the soul to be able to return to places I had enjoyed and explored as a younger version of myself, and yet on another level the changes I perceived were not all good. Beautiful glades of larch became choked with bramble, and grand trees I had known disappeared into the leaf litter.

A final farewell

My parents have been trying to sell their house for over two years. They want to move closer to my brother and I, but the sluggish housing market denied all attempts to move until very recently.

They have finally sold their house. I'm here in Suffolk right now, helping them make the final preparations. Tomorrow I accompany my elderly Grandmother to the new address in an ambulance (as she is unable to stand by herself and does not travel well), and on Thursday my parents exchange keys for the new house.

Today was my very last day alone with the landscape I have known for so long.

I chose to recreate a route I first walked in October 2003. From Sudbourne I walked down to the outskirts of Orford, then struck inland along the public footpath through the old estate of Sudbourne Hall (now largely farmland). It's a beautiful walk at this time of year when the trees are starting to turn, and there are several sweet chestnuts that give reliable crops of fat and juicy nuts. I picked up a pocketful of them as I walked.

The last time I did this route was several years ago and I couldn't help comparing today to my first visit. The avenue of horse chestnuts hadn't changed much, but there's a spinney of grand old beech trees a little further along, many of which are host to ancient carved graffiti. The giant beeches of the Sandlings are starting to succumb to fungus infections and, sadly, these are no different. Two of the biggest are gone entirely; another now exists only as a stack of mossed-over logs.

The beech spinney in October 2003

The beech spinney in October 2003

The same trees today. The central two beeches correspond with the trees in shadow

The same trees today. The central two beeches correspond with the trees in shadowon the centre right of the previous image.My route finished at the prow of grassland overlooking the Butley Creek. I've enjoyed many sunsets here and it's a place of extraordinary calm, miles from the nearest road and disturbed only by the warbling of wading birds. Walkers rarely visit; I've never seen anyone there but me. This is a beautiful hidden pocket of wildness and I've never found anywhere quite like it.

Butley Creek in 2005It feels incredibly strange to know that, in all likelihood, I won't return to these places — but I've actually been very fortunate. As I mentioned earlier, my parents have been trying to move for a long while and every time I came to visit I wondered if it would be for the last time. So I have said my goodbyes gradually ... and every renewed visit has been a gift.

Butley Creek in 2005It feels incredibly strange to know that, in all likelihood, I won't return to these places — but I've actually been very fortunate. As I mentioned earlier, my parents have been trying to move for a long while and every time I came to visit I wondered if it would be for the last time. So I have said my goodbyes gradually ... and every renewed visit has been a gift.I have been blessed with two extra years I didn't think I'd have: two years to wander around my favourite places with a renewed appreciation, fuelled by the knowledge that these visits couldn't continue forever. That's a precious thing.

Published on October 07, 2014 15:19

October 6, 2014

The Atholl Expedition featured in Mountain Pro Magazine

An extract from my second novel, The Atholl Expedition, has been published in this month's issue of Mountain Pro Magazine. It's a double page feature and the illustration of Forbes taking measurements at the Braeriach bergschrund looks particularly striking.

There's plenty of other good stuff in the magazine as well, including winter gear reviews and an extract from Guy Robertson's new guidebook, The Great Mountain Crags of Scotland.

You can read the magazine online for free here. A PDF version is available to download.

A reminder

The Atholl Expedition has been shortlisted for the Outdoor Book of the Year Award, but to win the title I need all of my readers to vote for me! You can vote here in category seven. I'd like to thank all of you who have voted so far and shared the link — it really means a lot. Support on Twitter in particular has been overwhelming.

There's plenty of other good stuff in the magazine as well, including winter gear reviews and an extract from Guy Robertson's new guidebook, The Great Mountain Crags of Scotland.

You can read the magazine online for free here. A PDF version is available to download.

A reminder

The Atholl Expedition has been shortlisted for the Outdoor Book of the Year Award, but to win the title I need all of my readers to vote for me! You can vote here in category seven. I'd like to thank all of you who have voted so far and shared the link — it really means a lot. Support on Twitter in particular has been overwhelming.

Published on October 06, 2014 04:57

October 2, 2014

Thought processing — analogue vs. digital

I've created a new blog post over on the Pinnacle Blog about how note-taking with pen and paper is completely different to digital note-taking ... and how going 100% digital appears to have eroded my biological memory.

It’s really surprising that I can still remember a lot of the stuff I wrote down in those old paper notebooks, but I have absolutely no memory of information recorded in digital files in the same year. That’s a wakeup call. I don’t like the idea of trading my own memory for convenience.You can read the full post here.

Published on October 02, 2014 08:04

October 1, 2014

The Atholl Expedition shortlisted for Outdoor Book of the Year Award 2014 — Please Vote!

Nominations have now closed for The Great Outdoors Awards 2014, and I'm delighted to announce that The Atholl Expedition made the short list for the Outdoor Book of the Year Award.

There are nine categories in the awards, and the books section is number 7. Other categories include Independent Retailer of the Year and Outdoor Personality of the Year. If you'd like to participate then you have to vote in every category. Polls close on the 10th of November.

Please vote for my book in the awards! I'm up against some stiff competition, including a book shortlisted for this year's Boardman Tasker Prize. I'd be very grateful if you could all vote for me and pass on the message.

Here is the link, and thank you all!

Published on October 01, 2014 08:24

September 25, 2014

When's the next book coming out, Alex?

2014 has whooshed past in something of a blur. My plan at the start of the year was to release three titles: one major novel, plus two shorter companion pieces. I’m sorry to say that I’m on track for releasing precisely nothing.

Work continues on A Year of Revolution — the sequel to The Atholl Expedition and the next volume in the Alpine Dawn cycle — but it’s nowhere near ready and I only have a few chapters completed. A Christmas release just isn’t going to happen, and at the rate I’m going it will take another six months. As for other titles, I have made progress on a science fiction short story for an anthology project, but that’s about it.

Worse still, 2014 has been a year decidedly light on mountains. I managed three trips. The first, in January, had to be called off due to terrible weather. In May we went to Edale for a few days, which was enjoyable, and in July I went to the Alps, which was a significant and worthwhile expedition. However, I’ve only stood on two summits all year and it’s starting to feel like a really long time since my last adventure in the Scottish hills.

Last year I was productive, discliplined, and made short work of Atholl’s first draft. I also managed to fit in several excellent trips to the mountains. So what happened this year?

Real life intervenes

Until recently I worked part time as a consultant at the Carphone Warehouse. This job worked reasonably well for me last year and I managed to fit both writing and mountaineering trips around my shifts (which generally didn’t exceed four days a week). The balance worked.

However, our manager left late in the year to help a struggling store and that’s when things unravelled. As a small team of four, we worked well together — but removing a key component changed the dynamics. Another member of staff left shortly afterwards, leaving just me and the new manager. We entered crisis mode. As far as I can tell, the store remains in crisis mode nearly a year later.

Early this year I was working 6–7 days a week. At first I thought this would just be for a month or so, until we found new members of staff, but somehow we failed to hire anyone for months. Few people applied for the job, and the candidates we called in for interview were astoundingly bad. Eventually we hired someone, but they only lasted two shifts.

After months of burning the candle at both ends, we finally hired someone who was actually suitable for the role. By this point I already knew that Carphone wasn’t working out, but it wasn’t until July that I made the decision to go freelance and establish Pinnacle Editorial. I owed it to my colleagues to wait until a reliable new member of staff was on board before I could leave.

Of course, from that point on I have been dedicating every working hour to getting my new business off the ground and establishing a client base. I’m glad to say that things are going well in that regard, and my working week is full of varied and interesting work, but I am not yet at the stage where I can relax and focus on other things. New ventures — particularly freelance ones — require time to nurture and grow.

Excuses, excuses

I know, I know. If I was a real writer I would have found time — etcetera etcetera. I’m aware of all the motivational ephemera floating around the Web that exists to make writers believe that if the words aren’t flowing out of them in a torrent at all times then they shouldn’t be doing it. The fact is that not all writers are alike, and for me much of the work of writing is an unconscious process that does not involve putting words down on the page. I can be sat staring into space and still writing. Most of the work is done by my characters, anyway … all I have to do is record what they are up to.

Being serious for a moment, there are also priorities to consider. Writing is not my main source of income. For most of this year I have had to prioritise the things that pay the rent.

Balance

It’s all about balance.

For me, the ideal balance allows me to dedicate several hours every week to writing — not necessarily every day, because I don’t have to write every single day to be productive. This balance would allow me to conduct my editorial work from 10–6 every day (my preferred working hours). It would also allow me to read for an hour or two in the evening, and give me the time and money to escape to the hills for a few days every couple of months. A day off every week for a long bike ride or hike through the Wolds is also an important ingredient.

This is the balance I am trying to build in my life. I very nearly hit it last year for a few months; the only sour note was the uncertainty and stress of a day job that I was never particularly good at.

In 2015 I will have more control over my life than ever before. I am master of my own time and can assign it as I see fit. The ideal balance will take a little while to achieve, and I have no doubt that I’ll have to continue prioritising my editorial work for much of 2015 … but I also know that I’ll only have myself to blame if I don’t find the time to write as well.

Thanks for reading, and if you’re one of my readers then thanks also for your patience. The new book is going to be worth the wait.

Published on September 25, 2014 05:36

Alex Roddie's Blog

- Alex Roddie's profile

- 27 followers

Alex Roddie isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.