Alex Roddie's Blog, page 5

December 24, 2014

Happy Christmas!

Published on December 24, 2014 03:07

December 21, 2014

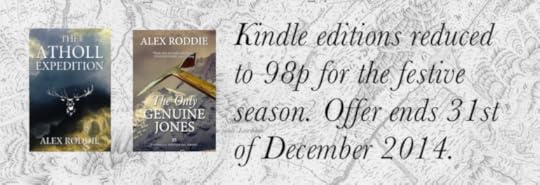

Kindle editions discounted for Christmas

As a Christmas gift to my readers, the Kindle editions of my two full-length novels, The Only Genuine Jones and The Atholl Expedition, have been reduced in price from £1.99 to 98p. This offer will run for ten days until New Year's Eve.

I'm afraid I don't have a new book to release this year, but if you have yet to read one of my existing titles — or if you are lucky enough to receive a shiny new Kindle for Christmas — then this is the best possible time to get involved.

If you'd like to help me out, please spread the word by sharing this blog post on social media or telling friends and family the old fashioned way, by word of mouth! Many thanks, and happy Christmas to all my readers.

The Only Genuine Jones

"A smooth read ... the author's passion for his subject matter is abundant on every page."TGO Magazine official review (April 2013)

"A smooth read ... the author's passion for his subject matter is abundant on every page."TGO Magazine official review (April 2013)"Read [it] as a novel and it's a real page turner, building up a flawed but believable hero in parallel with a villain that manages to elicit feelings of sympathy at times. Read it as a mountaineering book and you'll start questioning your own knowledge of history. Either way you'll be left wanting more."MyOutdoors official review

The Atholl Expedition

Shortlisted for the Outdoor Book of the Year Award 2014

"... an exciting and well-written adventure story but it also goes deeper into that, both into the history of the period and the psychology of the characters. It's one of the best works of mountaineering fiction I've read."TGO magazine official review

"... an exciting and well-written adventure story but it also goes deeper into that, both into the history of the period and the psychology of the characters. It's one of the best works of mountaineering fiction I've read."TGO magazine official review"A swashbuckling tale of outdoor adventure, bringing together some epic wild locations and great storytelling."TRAIL magazine official review

"A book for anyone who loves wild places and cracking good yarns ... I love the fictional/philosophical mix of Alex’s writing and he has a wonderful eye for the unseen."Review by outdoor blogger Alistair Young

Published on December 21, 2014 10:53

December 15, 2014

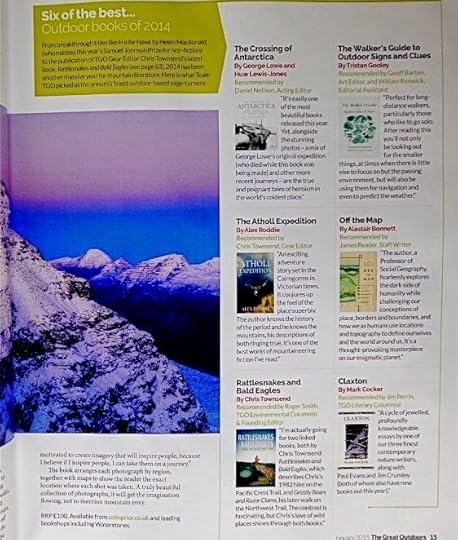

The Atholl Expedition listed in top outdoor literature of 2014

It's that time again when the outdoor industry looks back at the year past and reflects on the highs and lows. For the first time in my career I have been fortunate enough to feature in this great reckoning, not once but three times.

First I was nominated (and shortlisted) for the Outdoor Book of the Year prize at the TGO Awards in Kendal last month, and although I didn't come first it was great to meet a few people I'd chatted to online.

Second, the latest issue of TGO has mentioned The Atholl Expedition in an entirely distinct "Six of the best outdoor books of 2014" list. Unlike the Awards, this list was not compiled by a reader survey; titles were recommended by TGO writers and staff members. Chris Townsend, who is the Gear Editor of TGO (in addition to being a highly accomplished author in his own right), was kind enough to recommend Atholl for inclusion in the list.

Third, outdoor news website MyOutdoors today listed The Atholl Expedition in "Five of the best outdoor books of 2014". Other titles include Alpine Exposures by Jon Griffith, Banff Grand Prize winner One Day as a Tiger by John Porter, and Boardman Tasker winner Tears of the Dawn by Jules Lines.

A reflection on where I've come from and where I'm going

I still can't quite get used to my humble little book being mentioned in the same breath as these towering accomplishments of mountain literature. I spent much of 2012 struggling to believe my writing was anything but terrible, and much of 2013 surprised that a few people, gradually increasing in number, wanted to read it. 2014 has been a year of coming to terms with the fact that people actually think it's good.

I still can't quite get used to my humble little book being mentioned in the same breath as these towering accomplishments of mountain literature. I spent much of 2012 struggling to believe my writing was anything but terrible, and much of 2013 surprised that a few people, gradually increasing in number, wanted to read it. 2014 has been a year of coming to terms with the fact that people actually think it's good.I wonder what next year will bring?

I have long avoided the superlatives other indie authors sometimes apply to themselves, because I think understatement and humility can be more effective in the long run. I have seen the term "bestseller" bandied about recently but have resisted the temptation to use it myself. If a book has dipped into the top #100 cozy mysteries for five minutes, does that make it a bestseller — and does that make the author a bestselling author? Of course not. Yet I have seen "bestselling" books with shakier credentials than these.

I've seen some highly dubious interpretations of the term "award-winning" recently, too.

But you know what? Maybe I ought to start blowing my own trumpet just a little bit more. The Atholl Expedition has been in and out of the top ten bestselling mountaineering titles in the UK so often that I've stopped counting, and as I type this it's sitting at #11. It has occupied the #1 spot five times, for nearly a week on one occasion. The book has been reviewed in numerous mainstream publications and has not received a single bad comment from any quarter. I have come a hair's breadth from winning a competitive outdoor literature prize.

My first book came out a little more than two years ago, and my career is only just starting. I feel that I have made significant progress, particularly this year thanks to a good book which resonated with a lot of people — but I've been distracted by other projects and haven't capitalised on my successes.

In 2015 I'm going to hold my head a little higher and acknowledge my victories with a little more fanfare. Don't worry, I'm not going to start spamming my Twitter feed with relentless self-promotion or anything like that — but it's time I started putting more focus back into being an author rather than being an editor all the time. I'm confident you'll be hearing more good things from me in the New Year.

Published on December 15, 2014 09:01

December 12, 2014

The camera of the Abraham brothers returns to the Lakeland crags

Readers of my historical novel The Only Genuine Jones will be familiar with the brothers George and Ashley Abraham: climbing photographers from Keswick in the Lake District who teamed up with O.G. Jones to document many of his pioneering first ascents in the late 19th century. In my short story Crowley's Rival , Jones borrows a camera from the Abrahams' photographic studio and gets into difficulties while trying to descend a gully on Great Gable in the company of a young Aleister Crowley. This was a true incident documented from both sides of the dispute. In fact, it's arguable that the bulky camera tripod that made Jones so clumsy on the descent was partially responsible for the rivalry between Jones and Crowley, both in reality and my fictional narrative.

I was delighted to find out that one of the cameras formerly owned by the Abraham brothers has been loaned to the Mountain Heritage Trust, and currently resides in the Keswick Museum along with selected images from the Abrahams' collection.

This particular camera is an Underwood Instanto, manufactured by the E & T Underwood Company in Birmingham. This model was produced from around 1886 to 1905 and is made from mahogany and brass, with leather bellows. Although the Instanto was made in quarter plate, half plate and whole plate sizes, this specimen takes 10x12 inch plates. It's a gorgeous machine — but extremely bulky, which as we shall see is an important consideration for mountain use. The Instanto camera was sold for between £2 4s 6d and £6 2s when new.

The owner of the camera, who has loaned it to the MHT, is keen for it to be used once again in a mountain environment. On the 20th of April 2014 it returned to the crags of Scafell to take part in the centenary anniversary of the first ascent of The Great Flake climb on Central Buttress, which was one of the greatest pre-war rock climbs of the Lake District.

Professional photographer Henry Iddon is currently working on a fascinating project involving this camera. He intends to use the Instanto to record contemporary rock climbing images, in much the same way that the Abraham brothers used it to document the leading climbers of their era. I think anyone with an interest in either photography or mountaineering will agree that this is remarkable. Will a modern digital camera from the year 2014 still be operational a century from now? I very much doubt it.

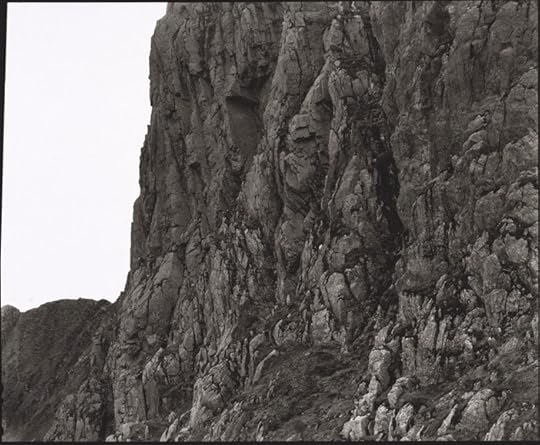

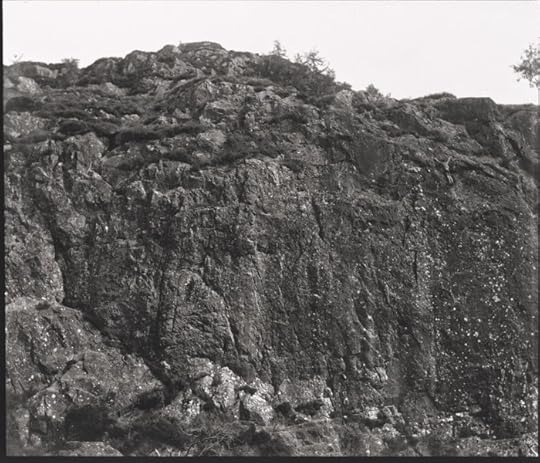

Central Buttress, Scafell. This is a contemporary image captured

Central Buttress, Scafell. This is a contemporary image capturedwith the Instanto camera.On a personal level, I find it extraordinary that a camera used by characters who feature in my works of fiction — and, indeed, it may even be the camera from Crowley's Rival — is still being used today. Projects like this make me very aware of both my privilege and responsibility in writing about these people and events.

I got in touch with Henry Iddon and asked him a few questions about the Instanto project.

1. Using a 19th century camera in the mountains must be dramatically different to using a modern DSLR, or even a more traditional film camera. What has the experience taught you about the skills and techniques of the pioneering mountain photographers?

Using the 10x12 is similar to using my 5x4 which I've been shooting "A Place to Go" on. Obviously the size makes it very cumbersome and you need a lot of space to operate it — loading a film into the dark slides is a performance as it needs a room, not a changing bag!

Everything has to be planned and worked through a process. Back then they used pre-prepared glass plates — we're using custom-made Ilford FP4 film which I source when Ilford do a bespoke service for unusual film sizes once a year, usually in August. Twenty-five sheets cost in the region of £160. We've also worked closely with Pete Guest at Image Darkroom in London.

After some trial and error we now know the process time for the film that gives a good negative. Because the camera has no shutter — exposure is by taking the lens cap on and off — and as we're using modern emulsion we're relying on processing and the exposure latitude of the emulsion to get a good exposure.

The Fell & Rock Climbing Club2. What are the main challenges in using such a bulky camera in the mountain environment?

The Fell & Rock Climbing Club2. What are the main challenges in using such a bulky camera in the mountain environment?As with any large format camera in an outdoor environment the big issue is wind. The camera, and particularly the bellows, act like a sail — and movement or vibration would result in a blurred image — so it is only feasible to use it on still days. It also takes a while to set up. Being literally a museum piece we have to handle it with care.

As there is no tripod fitting we've had a table made for it to sit in with straps across. This table has a film camera tripod bracket attached to it so we can use a hefty tripod designed for a pro video camera. It's remarkable to think that the American photographer Carleton Watkins shot the US landscape, including Yosemite, in the 1860s using a camera taking 18x22-inch plates. And in 1875 another American photographer, William Henry Jackson, astounded the photography world by packing a 20x24-inch plate camera into the Rocky Mountains.

3. What can you tell me about your future plans for this project?

The camera is now in the Keswick Museum until May 2015 as part of the Mountain Heritage Trust exhibition. The plan is to use the camera to photograph some notable climbing achievements of the present day along with some contemporary mountain landscapes. So a camera owned by those who were, in many ways, the first action sports photographers and used 100 years ago will be returning to active service and record the leading lights of now. At the same time we'll be contrasting it with the latest technologies such as the DJI Phantom drones.

James McHaffie climbing on Reecastle CragMany thanks to Henry for these fascinating details of the photographic project — and don't forget, if you want to see the Instanto camera yourself it is on display at the Keswick Museum until May.

James McHaffie climbing on Reecastle CragMany thanks to Henry for these fascinating details of the photographic project — and don't forget, if you want to see the Instanto camera yourself it is on display at the Keswick Museum until May.All images © Henry Iddon — All Rights Reserved.

Further reading

Visit Henry Iddon's websiteRead about the MHT Residency at the Keswick Museum"Climbing into War, a Justified Art" by Claire Carter: article on Siegried Herford and the first ascent of the Central Buttress

Published on December 12, 2014 03:42

December 11, 2014

Christmas paperback stock update

It's that time of year again! Paperback copies of my novels have been flying off the virtual shelves over the last couple of weeks, and I have received several queries about stock levels, so I thought I'd make an official update.

As of this morning, The Atholl Expedition is sold out on Amazon UK, and there is only one copy of The Only Genuine Jones left in stock.

My own personal stocks are also running very low. I have one signed copy of The Atholl Expedition available, and The Only Genuine Jones is sold out.

Other sources for my books

All is not lost — you can still order my books from Waterstones, direct from the printing firm, or (at a significant price premium) even from Ebay. Please note that most of these sources specify a longer delivery time, so you should order immediately to be sure of getting your copy before Christmas.

For full listings of sources for my books, including the eBook versions which are always available, see the book pages on my website:

The Only Genuine Jones

The Atholl Expedition

Published on December 11, 2014 03:27

December 1, 2014

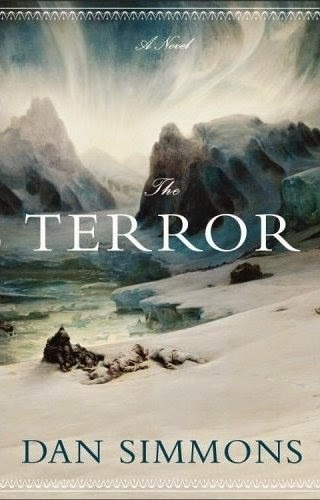

The Terror by Dan Simmons — Book Review

The Terror by Dan Simmons Book review by Alex Roddie

I discovered this book purely by chance. Someone on Twitter recommended I read The Abominable by Dan Simmons, but after reading the sample I found myself downloading The Terror instead. (The Abominable remains on my reading list.)

This is a very good book, but not quite as good as I hoped it would be.

This is a very good book, but not quite as good as I hoped it would be.The Terror tells the story of the John Franklin Arctic expedition, which took place in the mid–1840s with the objective of finding the Northwest Passage. Both ships, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, were lost with all hands (a total of 129 casualties). Little is known about the last days of the sailors and officers of these vessels, although evidence points towards a lingering end from starvation, scurvy and cannibalism.

This is very much a book of two halves. As an historical novel, The Terror is masterful. Simmons chooses a variety of characters to tell a story of an incompetent Royal Navy, numerous bad decisions, failure for the Victorian explorers to work with the native Inuit people or understand the Arctic environment, finally leading to the abandonment of both ships and an attempt to haul boats over the frozen sea. The result is the grim death of almost every single character.

This section contains spoilers!

Two of the main characters are Francis Crozier, captain of HMS Terror, and Harry Goodsir, surgeon aboard HMS Erebus. These two are deeply flawed — particularly the alcoholic Crozier — yet are, in my opinion, the most likeable and interesting characters in the story. They also perhaps have more common sense than the rest of the officers put together. Sir John Franklin himself is portrayed as a bigoted buffoon with a tendency to make poor choices as leader of the expedition, including the choice that led to both ships becoming stuck fast in the pack ice.

The story is initially slow-moving, with many scenes heavy on exposition and detail. There is also a great deal of jumping back and forth in time. If you can put up with these foibles, however, the gradually unfolding story of disaster is extremely rewarding.

The issue I have with this book concerns the supernatural / mythological aspect. Shipmates aboard the beset vessels are gradually picked off by a sort of demonic creature of the Arctic. At first it seems it may be no more than an uncommonly large polar bear, but as the narrative develops it becomes clear that the creature is a supernatural being. It’s cunning, patient, and has a macabre sense of humour.

Throughout the course of the novel, the “Terror on the Ice” devours a sizeable proportion of the crew. The creature is associated with a mysterious Inuit woman who has a habit of hanging around the ships and is nicknamed Lady Silence by the crew due to the fact that she has no tongue. Silence is feared but reluctantly tolerated by the explorers.

My problem with this subplot stems from the fact that it’s completely unnecessary. During most of the book, the Terror on the Ice acts as an uncomplicated bogeyman — a way of increasing external conflict in a narrative already charged with it. There is no need to make the harsh Arctic winter more terrifying by adding a monster as well. The characters dismembered by the monster would have died from starvation, scurvy, disease or mutiny anyway — which is exactly what actually happens to most of them. There is no need to add another way of killing off the characters. The hostile environment and the lack of knowledge of the explorers are quite capable of doing that alone.

Some of the main characters, pictured here a few

Some of the main characters, pictured here a fewdecades after the events of the story.In the climax of the story, Captain Crozier survives a mutinous assault in a manner that would make Rasputin shake his head in disbelief. There is then a frankly bizarre section in which Crozier becomes an Inuit shaman acting to help preserve the balance of the Arctic, of which the Terror on the Ice (or Tuunbaq) is a vital part. The Tuunbaq is, essentially, an Inuit god. Crozier is the only survivor of the John Franklin expedition.

I understand what the author tried to achieve here, and to an extent it does work. This subplot provides a satisfying conclusion to Crozier’s character arc and demonstrates how little the explorers were willing to learn from the environment around them. It also added an intriguing environmental angle. But, for me, the novel would have worked just as well without the supernatural elements, and may well have ended up more focused. There is a great deal of Western / American guilt behind this subplot, I think. The Inuit are portrayed as alien, but far more inherently virtuous and environmentally-friendly than the blundering explorers, all of whom die — except Crozier — as punishment for their ignorance. Reality is rarely so black-and-white, and I don’t think good fiction should be either.

Ultimately I enjoyed this novel for its rich depiction of a doomed Arctic expedition, but I felt that the mythological and supernatural elements served only to dilute the power of Dan Simmons’ otherwise masterful story.

Buy the book on Amazon UK

Further reading

Uncovering the secrets of John Franklin's doomed voyage

HMS Erebus found

Published on December 01, 2014 12:40

November 25, 2014

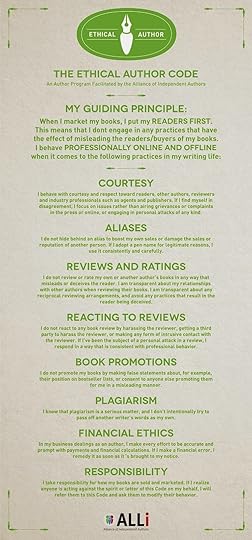

I Adhere to the Ethical Author Code

A new set of voluntary guidelines has been published to help keep writers on the straight and narrow. Most authors are honest in their dealings, but unfortunately there have been incidents where writers have falsified reviews, reacted poorly to bad reviews, copied the work of other people, or otherwise acted in an unethical way.

This is my declaration that I adhere to the Ethical Author Code.

Published on November 25, 2014 08:36

November 24, 2014

Alpine Dawn II progress report

"I lifted my eyes up to the heavens, and saw above me the eternal snowsof the Monarch herself, Mont Blanc."— James Forbes

Most of my progress reports on Alpine Dawn II so far this year have been heavy on excuses and light on progress, but I'm glad to say that work has resumed on this novel in a meaningful way. It won't be out in time for the end of this year, but a summer 2015 release is starting to look likely — and I believe a longer gestation time is creating a better book.

Working titles

Firstly there's the issue of what this book is going to be called. At this stage I really can't tell you. Working titles have included The Solomon Gordon Papers, Kingsley's Challenge, A Year of Revolution, and (most recently) The Invisible Path. The problem is that this novel is a window into a huge story played out by a large cast of characters over nearly seventy years, and over the last thirty-odd months my focus has changed more than once as I find the right viewpoints (in both time and space) for the story I really want to tell.

I have already written and discarded over sixty thousand words. This story matters to me, and it needs to be told in the right way. In some respects the birth of Alpinism is the greatest story ever told, and while I don't hold my own fictional take on these events to such an impossibly high standard, I am determined that it shall be the best it can possibly be.

At the time of writing I have thirty thousand words that will make it into the final version, but much remains to be done.

This is the first time I have worked on anything of this scale before. It's like an iceberg. The submerged portion is bewilderingly huge and it has taken me years to make sense of it, but I won't inflict all this backstory on my poor readers. The end result is being neatly packaged into the series of novels I call Alpine Dawn. I will have failed in my job if I can't tell this tale in less than two hundred thousand words, all said.

The beginning

It all began in 1784 in the remote village of Savoy known as Chamouni. A Genevan scientist and explorer, H.B. de Saussure, offered a cash prize to the first man who could stand on the summit of what was believed to be the highest mountain in the world: Mont Blanc.

Two friends, Jean-Marie Couttet and Jaques Balmat, searched for the route together. They were crystal collectors and chamois hunters by profession although both had started to earn a supplementary wage by guiding travellers over high passes.

On the 8th of August, 1786, the world changed. Balmat made it to the summit of Mont Blanc, but his companion was the physician Michel-Gabriel Paccard — not his friend Couttet. Couttet was bitterly disappointed that his name would be forgotten while Balmat's would live forever. He finally made it to the summit the next year, but it was the beginning of a feud that, in my fictional storyline, came to shape the 19th century and — ultimately — the destiny of the present day.

The actual narrative of Alpine Dawn II largely takes place in the years 1848-9, but I hope this taster has demonstrated that I am working with a story that goes far beyond the desires and fears of the characters I introduced to my readers in The Atholl Expedition. The book will be ready when it's ready, but I am confident that it will be worth the wait.

Published on November 24, 2014 05:14

November 22, 2014

Your story already exists

The story you want to tell already exists. As a writer, your job is not to make it up — it’s to illuminate the truth that’s already there.

One of the questions I’m asked most frequently about my books goes something like this: “How do you make your writing so detailed and believable?” I have given a variety of answers to this question in the past, and here are the usual explanations:

I do a huge amount of literary research, and have spent many years ensuring I’m as close to an expert on my subject as it is possible to be.I focus on creating believable characters who can take over the hard work of writing the plot for me (seriously — every novelist will tell you that this is a thing).I strongly believe in immersing myself in the world of my characters, and I have suffered to achieve that ideal. I have climbed Scottish mountains in winter conditions using Victorian climbing equipment, trekked Alpine passes discovered by my characters, slept rough on glaciers, been avalanched, climbed rock pitches in hobnailed boots without a rope, chipped steps up fifty-degree ice with an Alpenstock. I cannot write my books if I am not willing to suffer as my characters suffered.All of these answers are true, but they skirt around the truth.

The truth is that writers need to believe in their work. I don’t mean that in an abstract, motivational-slogan kind of way — I mean that in a very concrete sense. If you do not believe absolutely in the truth of what you’re writing, give up and go home. It doesn’t matter if what you are writing is a fictional interpretation of real events, or indeed something entirely imaginary; to you, the writer, your story must be true and you must believe in it without question.

So here’s the secret. For every book I write, I start with the assumption that my story already exists somewhere, and my job is merely to illuminate it — to shine a light on a truth that is as firm and solid as the mountains about which I write. Whenever I have tried to write a book from a different point of view, I have failed. If I find myself dwelling on issues like I need to figure out what happens next or how can I resolve the conflicts in this section? then I’m doing a bad job and the idea is probably a rotten one. The real questions are how can I find out what happens next? and how do the characters resolve their conflicts in this section?

The distinction is extremely subtle, and all in my head, but it makes an enormous difference to me.

Obviously planning and plotting still need to be done. The difference is in the approach. Rather than believing that it is up to me to come up with the answers, it feels more like a process of research. My job is not to decide what happens in the story; my job is to find out what happened, and then record it.

With my particular brand of historical fiction that isn’t such a difficult leap to make, because 70% of what I write about actually happened in some form or another — the fictional component is merely the glue that fills in the gaps. But it’s absolutely critical that the fiction is as real as the historical component, and I believe that writers in any genre can benefit from that philosophy.

If I can believe in a story so powerfully that it seems to exist with a truth beyond and outside my own mind, then the reader will believe in it too.

One of the questions I’m asked most frequently about my books goes something like this: “How do you make your writing so detailed and believable?” I have given a variety of answers to this question in the past, and here are the usual explanations:

I do a huge amount of literary research, and have spent many years ensuring I’m as close to an expert on my subject as it is possible to be.I focus on creating believable characters who can take over the hard work of writing the plot for me (seriously — every novelist will tell you that this is a thing).I strongly believe in immersing myself in the world of my characters, and I have suffered to achieve that ideal. I have climbed Scottish mountains in winter conditions using Victorian climbing equipment, trekked Alpine passes discovered by my characters, slept rough on glaciers, been avalanched, climbed rock pitches in hobnailed boots without a rope, chipped steps up fifty-degree ice with an Alpenstock. I cannot write my books if I am not willing to suffer as my characters suffered.All of these answers are true, but they skirt around the truth.

The truth is that writers need to believe in their work. I don’t mean that in an abstract, motivational-slogan kind of way — I mean that in a very concrete sense. If you do not believe absolutely in the truth of what you’re writing, give up and go home. It doesn’t matter if what you are writing is a fictional interpretation of real events, or indeed something entirely imaginary; to you, the writer, your story must be true and you must believe in it without question.

So here’s the secret. For every book I write, I start with the assumption that my story already exists somewhere, and my job is merely to illuminate it — to shine a light on a truth that is as firm and solid as the mountains about which I write. Whenever I have tried to write a book from a different point of view, I have failed. If I find myself dwelling on issues like I need to figure out what happens next or how can I resolve the conflicts in this section? then I’m doing a bad job and the idea is probably a rotten one. The real questions are how can I find out what happens next? and how do the characters resolve their conflicts in this section?

The distinction is extremely subtle, and all in my head, but it makes an enormous difference to me.

Obviously planning and plotting still need to be done. The difference is in the approach. Rather than believing that it is up to me to come up with the answers, it feels more like a process of research. My job is not to decide what happens in the story; my job is to find out what happened, and then record it.

With my particular brand of historical fiction that isn’t such a difficult leap to make, because 70% of what I write about actually happened in some form or another — the fictional component is merely the glue that fills in the gaps. But it’s absolutely critical that the fiction is as real as the historical component, and I believe that writers in any genre can benefit from that philosophy.

If I can believe in a story so powerfully that it seems to exist with a truth beyond and outside my own mind, then the reader will believe in it too.

Published on November 22, 2014 02:31

November 19, 2014

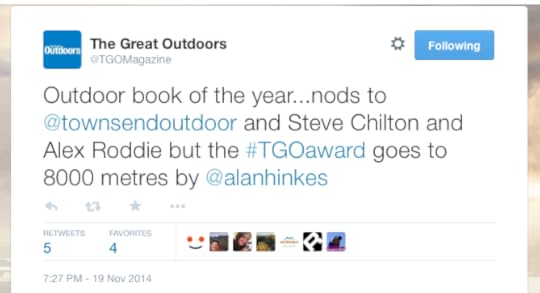

The TGO Awards 2014

Tonight I have been at the TGO awards event in Kendal. You may remember that my second novel, The Atholl Expedition , was shortlisted for the Outdoor Book of the Year category. I was invited to attend the event in which winners were announced.

Outdoor Book of the Year went to Alan Hinkes, Himalayan veteran and author of 8000m: Climbing the World's Highest Mountains. However, you'll notice in the Twitter screenshot above that I was given an honourable mention, along with Chris Townsend and Steve Chilton (both of whom I had the pleasure of meeting and chatting to tonight).

Obviously I would have preferred to have won, but to be honest I'm simply astounded that I got this far in a category dominated by towering figures in the outdoor industry. I must thank all of you for both nominating and voting for the book. I'm assured that a great many books were originally nominated, so the fact that I got so far towards the top says a great deal about the loyalty of my readers.

Lastly, here's a snap I took of Sir Chris Bonington accepting Outdoor Personality of the Year to an enormous round of applause.

Published on November 19, 2014 14:00

Alex Roddie's Blog

- Alex Roddie's profile

- 27 followers

Alex Roddie isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.