Lucinda Elliot's Blog, page 21

February 22, 2017

Review: ‘The Peterloo Massacre’ by Joyce Marlow

I hope I am joined by many writers – from the UK particularly – in aiming to write something to commemorate the bicentenury of Manchester’s Peterloo Massacre of 1819 coming up on 16 August, 2019 (if this post just happens to inspire any writers, there’s plenty of time; 18 months, in fact).

I began my researches by reading the 1969 book by Joyce Marlow on the historical background leading up to my events, and here’s my review of it.

‘This is an excellent depiction of the events and ideas leading to the tragedy of Peterloo. It centres on one of its most poignant victims, twenty-two year old John Lees, only the bare facts of whose life and death have come down to history.

We do know that he was, by a terrible irony, a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo. He is quoted as saying that he never felt so much in danger at Waterloo, as – to paraphrase – ‘Then it was one to one, but this was pure murder’.

While, through good luck more than anything, only fifteen at most people were killed, many more were seriously injured. The books of the relief commitees indicate perhaps as many as 500. Of these, many often horrifically injured by sabre and crushing wounds from being trampled on by horses many of whom, in those days before free medical treatment in the UK did not seek ‘official’ medical help.

John Lees himself, the son of a small cotton manufacturer in Oldham outside Manchester, for all his terrible injuries, did not see a doctor until the next day. He lingered, obviously developing terrible infection, for three weeks.

The coroner’s verdict over his death, and the attempts of local ‘justices’ to bring a verdict which vindicated the outrageous behaviour of the troops and the MYC (Manchester Yeomanry Cavalry) on that fateful day, underpinned the efforts of the establishment to quash radical dissent and outraged popular feeling. Locals agreed that John Lees had been sabered to death by troops during a peaceful protest. The magistrates who had sent in the troops so unadvisedly wished to prove that they had been dispersing a potentially dangerous mass uprising.[image error]

Sadly, the Radicals, too tame in their response to the outrage, did not take advantage of the mood of the times. The leaders were arrested, mostly on the day, and imprisoned for calling a meeting which, in demanding universal suffrage, supposedly attempted to overthrow the constitution. The government forced through ‘The Six Acts’ which effectively muzzled dissent and outlawed public meetings. It was decades before these were repealed.

The events of Peterloo led the poet Shelley to write these stirring lines in his ‘Masque of Anarchy’ (not in fact, published until the early 1830’s, ten years after his own death): [image error]

‘Rise like lions after slumber;

Rise in unvanquishable number;

Cast your chains to earth as dew,

Which on your sleep hath fallen on you,

Ye are many; they are few.’

A few days ago, an MP advised the British public (over a contentious speech by another MP) to ‘Rise up and switch off your television sets’. Always a good idea, that; but the bathos of the contrast struck me as grimly hilarious.

You can buy this book, among other places, on

February 10, 2017

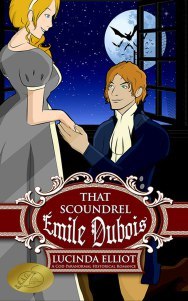

Conspiratorial Conversation Between That Scoundrel Émile Dubois and His Right Hand Man Georges

January 30, 2017

Mid Point Crisis in Novel Writing

[image error]Oh dear. It’s happened; I think I have come to the midpoint crisis in writing my latest.

This is the sequel to ‘That Scoundrel Émile Dubois’. I had already done the first quarter – about 40,000 before I broke off to write, ‘The Villainous Viscount Or the Curse of the Vennns’. As it combines and hopefully resolves many themes, it is epic length, about 120,000 words.

I have moved fairly smoothly through the next twelve thousand words, and now, I suddenly feel I am running out of steam.

Small wonder: I’m at approximately the mid point, and this is the point that so often causes much anguish. There are various pieces of advice available online.

Some of it is excellent, but I was a bit dismayed by the advice of one writer on these infamous mid point doldrums, basically, that you shouldn’t have them because you ought to have written a plan before you started writing.

I never write out a detailed plan. I know the beginning and the end, and I roughly know which way the story will go, but not in detail. Whether that is necessarily a bad thing I don’t know. I tend to think that it is.

Each time I swear that next time I will write out a plan. Each time I forget. That must say something about unconscious resistance to that highly sensible idea…

I certainly agree that the challenge of keeping the tension building, the conflicts increasing, and holding the reader’s interest until the end are of course, vital – and it is here that the novel cannot afford to be loosely structured.

[image error]One writer even stated that she usually abandons books at the mid point, rather than before. I find that interesting, as if I’ve read that far, a ridiculous sort of feeling that I mustn’t in some way ‘waste’ the effort that has gone before keeps me going. If I’m going to stop reading, it will be somewhere in the first quarter. I have, however, sometimes been guilty of stopping careful reading somewhere round this point, instead ‘skim reading’ either to a more interesting point, or if it doesn’t seem in my view to pick up again, to the end.

That is, of course, anyway a qualified success for the author, as I do want to know what happens in the end.

These ideas on avoiding the ‘sagging middle’ in a book by defining the turning point from this website are apposite:

http://www.writerstoauthors.com/story-structure-the-midpoint

‘What’s a midpoint?

A midpoint in the realm of story structure is the point where your character moves from reactionary to action. He makes the leap to start going after his problem instead of running from it.’

[image error]This information on the following link is a good reminder of the function of the middle of a novel:

http://www.aliciarasley.com/artmid.htm

‘Our openings and climaxes usually work pretty well because we know why we write them. The book’s opening has introduced the setting, the major characters, the themes, and the basic “problem” or premise of the plot. The climax brings all these elements together in an ending that explodes with released tension. But few of us know why we write the middle, except to join the beginning and the end.

But the middle is more than a transition from point C to point W. The important middle scenes develop conflict and explore the setting, characters, and theme, while moving the plot forward.

The plot purpose is the most obvious– the middle scenes present most of the events of the story , showing how each leads into the next. The cause-effect chain of the story events must be strongest here in the middle. At the end of the first few chapters, the protagonist has embarked on a journey, and every event marks an advance towards the destination. But we have to be ruthless here so that the journey isn’t a meandering one with too many blind alleys– every scene should be centered on an irrevocable event that changes the course of the plot.

The middle is the time of

rising conflict

, where the “on-the-brink” situation in the opening chapters gets more and more intense…

[image error] Another fundamental purpose is to develop the characters , especially the protagonist(s), so that their motivations are understandable and their actions clearly further the plot. These middle scenes also hint at and then gradually reveal any hidden issues or secrets within the major characters.

This is also where we develop the relationships between the protagonist and others. Their interactions, of course, will cause many of the important events– the conflicts, the alliances, the rivalries– that move the plot along.

The middle also has the purpose of deepening the “world” of the novel . Here you can explore the setting and its effect on the characters and events, examine the protagonist’s relationship to the society, and develop the themes or values that drive the protagonist and the society.

Most important, perhaps, is the evolving of the problem or question which drives the plot . If you’re writing a mystery, the problem is “whodunnit?” The question in a romance is “Why do they come to love each other, and how does this change them?” The middle of the book assembles the “evidence” that will eventually solve the problem or answer the question.

Finally, of course, the middle builds towards the climax , setting up the elements necessary for resolutions of the conflicts and the central problem or question…

The middle sags when some of the above purposes are unfulfilled, or fulfilled in a dreary way, or fulfilled not simultaneously but one by one. Experienced readers can identify these single-purpose scenes…

The middle can, however, be deepened and strengthened by following this advice: Have three purposes at least for each scene. One should be “advance the external plot”. For the others, consider these:

Develop character.

Show character interaction.

Explore setting or culture and values.

Introduce new character or subplot.

Forward subplot.

Increase tension and suspense.

Increase reader identification.

Anticipate solution to problem.

Divert attention from solution (but still show it).

Show how character reacts to events or causes events.

Show event from new point of view.

Foreshadow some climactic event.

Flashback or tell some mysterious past event that has consequences now.

Reveal something the protagonist has kept hidden.

Reveal something crucial to protagonist and/or reader.

Advance or hinder protagonist’s “quest”.

Obviously you won’t usually pick out three of these purposes and deliberately insert them into a scene. Rather, realize that action, dialogue, narration, description, and internalization can all be used in the same scene to add greater depth.’

So, taking all this fine advice into account, I hope I will yet survive not having a detailed plan (returns, sourly, to the keyboard, glaring at it as if it were an enemy)…

January 17, 2017

Originality and Breaking the Rules in Wrting

[image error]When I first started writing, it was in the days before the internet. The aspiring writer had to seek out and buy a ‘How To’ book, or borrow it from the library.

The first of these that I read contained this helpful piece of advice from the male author, very successful, but you might say, ‘one of the old school’. I have never forgotten his words, either: ‘If you can’t think of anything else to write about, write about your dog, or your wife.’ Seriously, in that order.

But I digress…

For many years now, for excellent writing advice, you can go online and in a few keystrokes, locate many websites full of suggestions and guidance for aspiring and already published (self and traditional) writers about the technical issues of writing and the latest market trends in publishing.

It invaluable to have so many sources giving varied advice regarding such key matters as the issues surrounding the need to have a clearly defined protagonist, point of view, how to create believable and interesting characters, the perils of having a Mary Sue or Marty Stu main character, and all the rest of it.

[image error]If one is interested in following market trends in publishing, and the latest rumoured top hates of agents, then one can find all sorts of discussions about those.

Writing from the second person point of view is, I think, the only one that strikes a chord with me.

It seems that the current pet hates among literary agents and publishers also include a prologue, a story starting with the main character starting awake from a dream which indicates psychic communication, plus – bizarrely – large blocks of italics. I must say that I consider that last to be unreasonable, as it is a convention that letters etc should be depicted in italics. If we have a long letter in the story, are we then supposed not to put it in italic form?

And finally on these hates of agents and publishers, it seems that they hate brackets, too.

And that isn’t even starting on the ways they hate various themes, ie, hate children’s stories about discovering hidden treasure in a sinister secret passage in a castle (rather strange: I never met a child under nine who didn’t emjoy a story about that).

[image error]Quite honestly, it does seem to be getting to the point where agents should state what they don’t hate, rather than what they do, because it would surely be briefer.

But it also seems to me, with all this talk and advice about writing styles and what agents and publishers find desirable, what is currently fashionable among readers, and all the rest of it, that something important is being neglected.

Originality in writing means breaking the rules.

Originality means thinking outside the box, and writing the story the way it flowed from your fingers during one of those wonderful times when the story seems to write itself.

We all are all – hopefully- inspired by great writers. To name just a few who have personally inspired me, Shakespeare, Mary Shelley, Jane Austen, Alexander Pushkin, Turgenev, Elizabeth Gaskell, all the Bronte sisters, George Elliot, Balzac, Zola, Joseph Conrad, Bram Stoker, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, H G Wells, George Orwell, Irwin Shaw, Patrick Hamilton, Harlan Ellison, Susan Hill, Stephen King and Margaret Attwood…

Of course, that’s failing to mention of my many talented indie author associates. I’ll spare their blushes, but several have inspired me.

But the main thing is, we mustn’t write like those writers we admire.

We can hopefully learn many things from them about structure, plot, characters, and all the rest of it. To name just one instance, when I read Harlan Ellison’s ‘Repent Harlequin Said The Ticktockman’ at fourteen, I saw a demonstration of how writing about a dystopia doesn’t have to mean writing a story without absurdity. Absurdity and horror so often go hand in hand.

But finally, if we want to try and write something original, something memorable, we must strike out on our own, like youngsters breaking away from parental control. That is what the writers we admire did. Their writing would not stand out if they hadn’t. We don’t want to write a second rate version of what someone has already done.

That – and I know I have said it before – is why finally we should go with our instincts about writing, even if it sometimes means going against the flow.

Because – and again, I know I have said much the same in a previous post – we may shelve an idea we love, because it breaks some rule or other. And who knows but some other writer may not produce a book which becomes all the rage, and which breaks exactly those rules to which we kowtowed.

[image error]I’m not saying that it’s a good idea to send out manuscripts which, just for the sake of it, begin with a prologue in dream form, are written from the second person point of view, crammed full of italics and brackets, and feature treasure hidden in secret passages.

Well, come to think of it, maybe it is. It would be funny to see those agents and publishers’ faces…

Leaving that wonderful vision aside, I do think if we keep too closely to the rules, we risk sacrificing our own individual style.

January 1, 2017

Writing Resolutions for the New Year: Why Writers Might Take a Look at That Unfinished Manuscript in the Drawer

[image error]I wonder what people’s writing resolutions for 2017 are?

My personal writing resolution is to finish the sequel to ‘That Scoundrel Émile Dubois’ and then, if there is time, to get a novella out which commemorates the St Peter’s Field Massacre of 1818.

I had already written the first third of that sequel in the first six months after publishing ‘Ravensdale’ back in 2014. But then I allowed myself to be distracted by other projects – including the one that ended up as ‘The Villainous Viscount Or the Curse of the Venns’.

I had all sorts of difficulties with that one. At one point, I had weeks of writer’s block – really dismal – I did a post about that on this blog.

I wrote 50,000 words of a serious version, and 22,000 words of a frivolous version, and I worried over a conflict between the strain of the comic mode of presentation and the tragic back story –but in the end I thought that I had found a way round that – and I hope that readers agree. The result is dark comedy, and perhaps that is the approach that suits me best. Well, there is one chapter which is not comic at all – and that’s the tragic backstory involving a forced abduction.

Anyway, all that took ages to resolve.

But back to the present. Now, I resolve not to let anything in the writing line distract me for too long from that sequel – not even the novella I have been musing over these past few months on the St Peter’s Fields, the horrible ‘Peterloo’ Massacre of 1818 – though I do want to publish a novella in time to commemorate the bicentenary of that event.

I must admit that getting the B.R.A.G award for ‘That Scoundrel Émile Dubois’ did encourage me to get back to working on more of the eponymous scoundrel and Sophie’s adventures (not to mention those of Ravensdale and the one-time-highwaywoman Isabella) – and I’ve been working on it since November.

I hope that a lot of writers are making similar New Year’s resolutions about that Project in Abeyance. There’s so much promising writing, so many projects started out full of hope that end up that way, so it would be good if we all unearthed the good ones.

The awful thing is, if it is left too long, that Project In Abeyance threatens to become The Manuscript in the Drawer, and for manuscripts, that’s like being in cast into a dungeon and forgotten.

After all, as I have commented on this blog before, one of my favourite novellas, Alexander Pushkin’s ‘Dubrovsky’ ended up as incomplete because he put it to one side, and never got back to it.

This, one of the first ‘robber novels’ was an attempt to combine genre writing with literary merit. He hoped to extend the borders of genre fiction (sound familiar on this blog?)

As such, ‘Dubrovsky’ was a source of inspiration for me to write ‘Ravensdale’, particularly in the comic scenes where the outlaw hero shakes with passion when he disguises himself as a librarian in the house of his true love Isabella, and comes upon his true love.

In the manner of a true late Regency hero, that is exactly what Dubrovsky does when he enters the house of his own true love, Aurelia, disguised as a humble tutor.

Pushkin, after working steadily on ‘Dubrovsky’ for about 33,000 words in 1832, put it aside – perhaps through problems with the structure and possibly, waning interest after that first rush of enthusiasm – never to return to it.

Unfortunately, the remaining years left to him were few. He was mortally wounded in a duel over his wife only five years later. ‘Dubrovsky’ was only published posthumously in 1842.

That is the problem with laying things aside, though it is unlikely that many writers will be killed in duels in the coming five years. But it is so easy for a writer to adopt the ‘out of sight, out of mind’ attitude to what was possibly something really promising, and to be distracted by other projects to the point that s/he or he never returns to it.

[image error]I hope that I have made the case for those sad, neglected, lonely Manuscripts in the Drawer being worth a second glance. Some have been left incarcerated for so long that they may have been stored on the memory of BBC micras (in the UK, that is, or on Smart). They are suffering like the Counts of Monte Christo and their plight should arouse compassion.

There are, admittedly, if my own early writings are anything to go by, some of these which were abandoned with good reason, which certainly will never deserve to see the light of day again. There was one of mine, written when I was perhaps thirteen and clearly inspired by Norah Lofts’ ‘Madselin’ (Marcher Baron, anyone?) that literally made me cringe.

But, if anyone reading this were to take a moment to glance through his or her own manuscripts in a drawer, it might lead to something really worthwhile being hauled out from the dismal company of (I hope the contents of this drawer of mine was more rebarbative than average) a dead spider, a sweet wrapper, a battered how to booklet on Making Money From Your Writing and a grubby pound coin (was that all the money I managed to accumulate from the said booklet?)

Anyway, Happy New Year, everyone.

December 21, 2016

Christmas Reading and Enjoyable Escapism

[image error]Sometimes I can be sceptical about people going in for a massive amount of escapist reading. For instance, I’ve met people who read an average of five male adventure stories or fantasies or romances a week, fifty-two weeks a year. That – even with my just-prior-to-Christmas just ticking over brain – amounts to 260 a year, and when someone is doing that amount of escapist reading, that might indicate avoiding some serious problem in real life that needs urgent attention.

But perhaps that problem is insoluble – or one that will resolve itself in a few years but currently must be endured – in which case, a retreat into escapism is surely sensible.

And I have to admit, if I’d written 260 books I would find it hard to criticise anyone who spent every evening with his or her nose buried in them…

And I have to admit, too, that there is some justice in the argument that authors spend too much time immersed in our fantasy worlds.

But a bit of escapism is refreshing. It’s nice, sometimes, to be completely uncritical and self-indulgent, particularly at this time of year. In the New Year, we can leap up to tackle the world’s problems with new enthusiasm. Well, possibly we will waddle along to confront them, given that we will have gained on average three pounds.

I like settling down with a book and a mince pie and either a cup of tea or a glass of sherry, or even of mulled wine, while the wind howls outside. I no longer live in the isolated old houses in which I grew up, but I do live on a hill, anyway, where it’s often windy. I don’t have a real log fire these days – but a radiator will do as well (and having been brought up with open fires, while I miss them I know all too well how tiresome they are to light and clean up after day after day).

I was reading Mari Biella’s excellent recommendations for Christmas reading. She’s beaten me to it with ‘A Christmas Carol’.

Christmas Crackers: The Best Festive Reads

Well, as I have often jeered at the insipid nature of Dickens’ heroes and heroines, and commented with disgust besides on his treatment of his wife, it seems only fair to show a flash of Christmas charity and recommend one of his books; besides, sentimental as it is, I do like that one.

[image error]

For sheer escapist fun, I don’t think you can beat Sherlock Holmes short stories at Christmas. For instance, there is the first collection I ever read, ‘The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes’. My favourite is ‘The Speckled Band’. There’s a Christmas story in it too, ‘The Blue Carbuncle’. That one is also interesting as a reminder that in the UK, goose was traditionally the fowl eaten at Christmas – by those who could afford it, anyway.

Then, for short ghost stories, I highly recommend ‘The Old Nurse’s Tale’ by Elizabeth Gaskell.[image error]

That one is truly alarming. Then, ‘Mr Jones’ by Edith Wharton is another fine spine chiller.

For something both fun and spooky – with the borderline between the psychological and the supernatural there, but only just –last year I read the fine novella by the above quoted Mari Biella: ‘Wintergreen’.

[image error]I recommend it for seasonal enjoyment, and for another atmospheric winter read, her vampire story, ‘Pietra’.[image error]

Or, for a full length tale of terror, there is, of course, Susan Hill’s ‘The Woman in Black’.

Seasons Greetings to everyone. Now, where is that heated mince pie and that glass of sherry?

December 8, 2016

Book Titles: Choosing a Title and some Good, Bad, and Indifferent Titles from Classic Novels

Titles are always difficult to decide on. This is all the more of a challenge, as the conventional wisdom of innumerable writers websites says you have to have an outstanding one that will make your readers want to start reading at once: – not an easy task.

Titles are always difficult to decide on. This is all the more of a challenge, as the conventional wisdom of innumerable writers websites says you have to have an outstanding one that will make your readers want to start reading at once: – not an easy task.

Well, I find them difficult, anyway. I was stumped as to what to call the Sophie de Courcy and Émile Dubois story, until I realised that I had the title in the text in the quote from Lord Dale in Émile’s days as a highwayman: – ‘You’re that scoundrel, Émile Dubois: i can tell by your eyes!

I believe this is often true (having difficulty in finding a good title, I mean, and then finding it in a line in the story, not identifying highwaymen by their eyes). That’s handy, given the sickening number of times an author must edit, re-write, and edit again. You can read through looking for a possible title, and the great thing is, these days, it doesn’t have to be conventional; it can be a question, or a threat, as in Harlan Ellison’s classic dystopian fantasy, of which more below…

I am never sure how far titles influence me as a reader. I would say only occasionally when I was younger, and perhaps more often now. Covers often interest me more. Perhaps I have become less visual?

I was pulled in by a several titles, though, even then. For instance, when I saw that one of the late Philip K Dick’s: ‘Flow My Tears,’ The Policeman Said that acted as a hook at once (I would dispute that his surname had a Freudian effect on me, though!) .

‘Repent Harlequin!’ Said The Ticktockman by Harlan Ellison was another. I knew I’d have to read that or burst, though I was fourteen at the time, and cynical about almost everything.

The Philip K Dick novel disappointed me slightly, though at the end the meaning of the title, elusive throughout , was finally illuminated.

‘Repent Harlequin!’ Said The Ticktockman is surely a work of genius. I gather that it has won classic status, and deservedly.

For anyone reading this blog who hasn’t read that story, I would urge, do, even if it’s the only piece of fantasy you ever read. It is horribly prescient. Written circa 1967, it prefigures our present day Culture of Hurry in a hideous but comical dystopia of a world governed by clocks. The very rhythm of the story is reminiscent of the ticking of a clock out of synch.

It is grotesquely comic, and highly tragic. It’s wonderfully constructed, though this is done with such mastery that it seems almost by the style that it was slapped together accidentally.

Oddly enough, I have never read a review on it, so these opinions are just ‘off the top of my head’.

Oddly enough, I have never read a review on it, so these opinions are just ‘off the top of my head’.

But some other classic best sellers have, to say the least, lacklustre titles. It would seem that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, for instance, nobody was that bothered about a title as a form of advertisement. A title seems to have been used as a means of summarising the book, rather than that of selling it.

Samuel Richardson’s Pamela anybody? Well, that does have the subtitle, Or Virtue Rewarded. I am sure that those who have borne with me through many blog posts know at once what my take on that is: ‘Moral and religious hypocrisy and toadying to your would-be rapist rewarded, more like!’

For sheer yawn inducing, try the title of the today little known sequel: Pamela in Her Exulted Condition. Yes, and the story isn’t much more exciting.

Richardson’s Clarissa has a dull enough sub-title: The History of a Young Lady. Maybe that was too put off those readers with perverted tastes who might plough through six of the seven volumes for the fun of the rape (which anyway, takes place offstage to maintain propriety).

Then there is Fanny Burney’s Evelina. That’s a nice name, and unusual, but not exactly a descriptive title. Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones and Joseph Andrews are even less titles that are likely enthral: unlike Richardson and Burney’s, they don’t even have unusual names.

In fact, I have been guilty of calling a novel simply after the name of a main character myself – in ‘Ravensdale’. I liked title, as both the protagonist Reynaud and the antagonist Edmund share that surname, and it is the name of the earldom which Edmund covets; besides which, ravens are seen as birds of ill omen and they circle about at the climatic points of the story. Still, potential readers don’t know that.

Another early novel is a favourite mine of the so-bad-it’s-good category Rinaldo Rinaldini, Captain of Banditti. That is probably a title that promises much blood and thunder in the original German. I don’t speak or read, any German, so I couldn’t say. In that English one, it sounds like a take off of some school story of the mid twentieth century: Renny Reynolds, Captain of the First Eleven, or some such.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a name difficult to detach from its lurid reputation, but removed from that, it isn’t much of an advertisement for the excitement of that truly terrifying story.

Then we go on to the more intriguing, but sedate, titles from Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Mansfield Park etc.

Jane Eyre and Agnes Grey are again far from riveting titles; Wuthering Heights and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall are a bit more likely to stimulate interest.

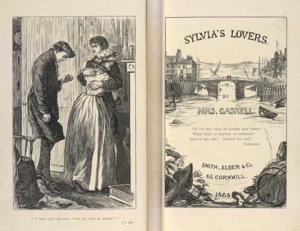

Elizabeth Gaskell was another person who went in for sedate titles. Mary Barton, Ruth and North and South etc. Sylvia’s Lovers might be considered to be shockingly risqué for this most Christian of authors –except for the fact that ‘lovers’ had a completely respectable meaning in mid nineteenth century UK…

Elizabeth Gaskell was another person who went in for sedate titles. Mary Barton, Ruth and North and South etc. Sylvia’s Lovers might be considered to be shockingly risqué for this most Christian of authors –except for the fact that ‘lovers’ had a completely respectable meaning in mid nineteenth century UK…

Her one time editor Charles Dickens knew how to market writing – how to end his serial pieces for his magazine on a cliff hanger, and how to appeal to his audience – and yet, his titles were hardly of the sort likely to send rushing to buy a copy – A Tale of Two Cities, Domby and Son, Hard Times etc. For all that, he was of course, the most successful author of his age. He did seem be fascinated by bizarre surnames and of course, these often feature as titles, ie, Martin Chuzzlewit.

Then, at the beginning of the twentieth century, we have one of the most famous novels ever to be published in the UK – so famous that it is hard to detach the name from its reputation – Dracula. That name is taken from the title of the sinister ‘Vlad the Impaler’ of fifteenth century Transylvania, Vlad Tepes. It seems that nearly until publication, Bram Stoker was going to call the book, The Dead Un-Dead.

Then, at the beginning of the twentieth century, we have one of the most famous novels ever to be published in the UK – so famous that it is hard to detach the name from its reputation – Dracula. That name is taken from the title of the sinister ‘Vlad the Impaler’ of fifteenth century Transylvania, Vlad Tepes. It seems that nearly until publication, Bram Stoker was going to call the book, The Dead Un-Dead.

Bland as many of those nineteenth century titles are, it is interesting how a slight alternation would make them either ludicrous or totally boring.

Balmy Valleys by Emily Bronte.

The Tenant of Mellow Meadow Bungalow by Anne Bronte.

A Saga of Two Suburbs by Charles Dickens.

Sylvia’s Acquaintances by Elizabeth Gaskell.

Flat 2B, Mansfield House, Mansfield Road by Jane Austen.

Humility and Open Mindedness by Jane Austen.

They do certainly lose an allure, so there must have been some thought given to those original titles, sedate or not…And on Dickens, how come I forgot last week to include the supremely dull hero of A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Darnay as a Marty Stu hero from a classic novel, and Lucie Manette as an example as a true Mary Sue in my post of the week before?

November 24, 2016

The Marty Stu or Gary Stu – Neglected Compared to the Mary Sue

I’ve been looking for discussions about the male equivalent of characters defined as Mary Sue’s online, and what interests me is how few posts there are about Gary Stus and Marty Stus,and how few male characters are defined in this way.

I’ve been looking for discussions about the male equivalent of characters defined as Mary Sue’s online, and what interests me is how few posts there are about Gary Stus and Marty Stus,and how few male characters are defined in this way.

In fact, I read a blog which, while admitting that there are few Gary Stu discussions compared to all those Mary Sue accusations flying about, didn’t explore this, going on instead to list various heroines perceived by the author as Mary Sues. I was surprised to find Elizabeth Bennet on this blogger’s list; but more on that later.

Goodreads has a ‘Listopia’ list of Gary Stus. As I am not a great reader of current fantasy, and most of the male leads named came from this genre, I didn’t know enough about the characters to comment. Even I, however, knew the male leads from the top two. First on the list was Edward Cullen from ‘Twilight’ by Stephanie Myer, and second was Jace from ‘City of Bones’ by Cassandra Clare.

Well, I think I said in my last post that the fact that many readers define the heroes and heroines of these books as Marty Stus or Gary Stus seems to have done little to detract from their bestselling status and continuing popularity.

I did let out a hoot of laughter at seeing that the tiresome ‘Little Lord Fauntleroy’ featured on this list, that infamous young Cecil of the sailor suits and suave compliments.

I added the hero of Fanny Burney’s ‘Evelina’ to this list. Lord Orville is, surely, the original Marty Stu, perfectly matched to the heroine who competes with Pamela for the title of the original Mary Sue.

I added the hero of Fanny Burney’s ‘Evelina’ to this list. Lord Orville is, surely, the original Marty Stu, perfectly matched to the heroine who competes with Pamela for the title of the original Mary Sue.

Lord Orville is handsome, witty, suave, gallant, and unlike his roguish rival, Sir Clement Willoughby, tenderly respectful of the heroine’s innocence (this is off topic; but did Jane Austen borrow Clement Willoughby’s name for her own rogue in ‘Sense and Sensibility’?).

I also added the secondary hero of Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ to the list. Charley Kinraid ‘the boldest Specksioneeer on the Greenland Seas’ is handsome, fearless, irresistible to women, can drink endlessly and never fall down, is a brilliant raconteur, beguiling and the life and soul of the party. Just about the only person who doesn’t admire him in the book is his jealous rival Phillip Hepburn.

Not only that, but he has so much good luck that he is virtually indestructable. He survives two serious gunshot attacks without seemingly lasting ill effects. A woman is rumoured to have died of a broken heart after he finished with her.

The only bad luck he has is falling victim to a press gang, and the Royal Navy officers quickly take to him and realizing his exceptional abilities, promote him so that within a few years, he is able to marry an heiress. Then, further promoted to Captain, he is able to send out press gangs of his own…

As the term ‘Mary Sue’ (later mutated to ‘Marty Stu’ or ‘Gary Sue’ to accommodate male characters) originated in fantasy fan fiction, I suppose it isn’t surprising that most of these online discussions are about this genre.

I did find a very witty catalogue of types of Marty Stu on this link. Unfortunately, it’s about those on television rather than in books. It is excellent, and the types are easily recognizable in novels as well as television series and films:

http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/MartyStu

This biting paragraph is particularly apt:

‘Dark Hole Stu: His gravity is so great, he draws all the attention and causes other characters (and, often, reality itself) to bend and contort in order to accommodate him and elevate him above all other characters. Characters don’t act naturally around him – guys wish to emulate him and all the girls flock to him regardless of circumstances. They serve as plot enablers for him to display his powers or abilities, with dialogue that only acts as set-ups for his response. He dominates every scene he is in, with most scenes without him serving only to give the characters a chance to “talk freely” about him – this usually translates to unambiguous praise and exposition about how great he is. Most people don’t oppose him and anybody who does will quickly realise their fault in doing so or just prove easy to overcome. Often a combination of the above Stu archetypes…’

Nevertheless, looking about for Marty Stu or Gary Stu discussions, I am a bit perturbed. There was seemingly so much more talk of Mary Sues on the web compared to that centering on their male equivalents.

This seems accurately to reflect the different standards and expectations applied to male and female characters. There does appear to be a good deal less resentment of male characters presented as admirable, handsome, unflappable, invincible in fights, and invariably attractive to most women.

A male character is permitted to have glaring character flaws and still be presented as generally heroic. He is also allowed to be sexually adventurous and even promiscuous; a female character so free with her favours would be defined as ‘slutty’ and lose the sympathy of many female, as well as male, readers.

In fact, being emotionally challenged is often seen as a desirable attribute in these stereoptypical male leads. It is only rarely one with female leads. This has led me to wonder how readers would react, say, to a female version of the Byronic male?

This strikes me at least as being unfair.

I also note, that for some reviewers, the term ‘Mary Sue’ is applied rather loosely, being leveled at almost any female character whom they for whatever reason, resent.

This leads me back to the term being applied by one blogger to Elizabeth Bennett. She doesn’t seem to me at all to qualify.

Yes, she is lucky to attract the hero’s admiration, but she does that through wit rather than her looks, which as everyone knows, originally elicited that ‘not handsome enough to tempt me’ remark from him. It is true that her mother doesn’t appreciate her, and a virtual requirement for Mary Sues is not to be appreciated by her family – but she is her father’s favourite daughter.

Apart from wit and dancing, she has no particular skills apart from perception. In the book (as distinct from the film versions) she is depicted as a mediocre singer and pianist; her sister Mary in fact described as more skilled, but with an affected style, so that people find her performances tiresome.

I suspect that the blogger disliked the character of Elizabeth Bennett, but not because she is a Mary Sue. Possibly, the blogger disliked her because she is generally such a favourite among Jane Austen lovers that the chorus of praise from them becomes boring.

Therefore, it would be good if readers applied that suggestion I found on a fan fiction website about Mary Sue’s: ‘Would I find these characteristics so annoying if she was male?’

Finally, a highly perceptive remark from a male poster called Tim Kitchin on Gary Stu’s:

https://www.quora.com/Who-are-the-most-notable-Mary-Sue-characters-in-books-and-literature

‘Jason Bourne, Tintin, James Bond, Ethan Hunt would all ‘fit the description’. The absurdity of these Gary Stus doesn’t go unremarked by fans, but it doesn’t seem to evoke the same cultural baggage and resentment as many Mary Sue characters – for one thing because the intrinsic role-conflict (for which read ‘socially conditioned expectation’) inside male character leads is less complex…and for another because we are so used to them..’

November 15, 2016

That Scoundrel Émile Dubois’ is a Winner of the B.R.A.G Medallion for Outstanding Fiction

‘That Scoundrel Émile Dubois’ is a Winner of the B.R.A.G Medallion for Outstanding Fiction.

Winning this award really made my day. I had entered my first book, the paranormal –historical- romance satire of Gothic, ‘That Scoundrel

Émile Dubois’ just hoping that I might be one of those whose books are considered to be of a high enough literary standard to be awarded that medallion. Still, I wasn’t unduly optimistic – for who doesn’t consider their own work to be good? We wouldn’t carry on writing in the face of all discouragement if we didn’t . There are far easier ways to make money. – So, when I opened the email, informing me that I had won the award, I did a dance!

I would like to publicize this opportunity for the benefit of other Indie writers.

For those followers of my blog who are self-published authors, and interested in entering, the B.R.A.G website was set up by a group of experts connected with writing who saw the main problem for Indie authors: – that because there is no quality control, all self-published works are often dismissed wholesale as being by definition poorly written and badly edited.

To quote from the website:

According to publishing industry surveys, 8 out of 10 adults feel they have a book in them. But traditional or mainstream publishers reject all but a tiny percentage of manuscripts. Historically, this has presented a classic catch-22, in that you had to be a published author in order to get a publisher.

The advent of self-publishing companies and print-on-demand technology has changed this. Now anyone can publish a book and the number of books being self-published is exploding, reaching into the hundreds of thousands annually. However, there is virtually no control over what is published or by whom, and industry experts believe that up to 95% of indie books are poorly written and edited.

Compounding this problem, these books are rarely reviewed in The New York Times Book Review or by other leading sources. Additionally, the reviews and ratings at online booksellers are often provided by the author’s friends and family, and are therefore unreliable.

There are professional book review services and writing competitions within the self-publishing industry that help address this problem. However, none provide an independent, broad-based and reader-centric source to advise the public which indie books merit the investment of their time and money.

This is precisely the reason that indieBRAG and the B.R.A.G. Medallion exist. We have brought together a global group of readers who are passionate about reading, and who love to help us discover talented self-published authors.

There is a fairly long wait – four months or so. I gather that the B.R.A.G website is always on the look out for readers, too.

There is a fairly long wait – four months or so. I gather that the B.R.A.G website is always on the look out for readers, too.

Here’s the link.Here’s the link

I was particularly pleased that ‘Émile won this award, because he and Sophie have always been my favourites out of all my characters and are the lovers whom I love best to write about.

I am very fond of the romantic Reynaud Ravensdale and his amazonian lady love Isabella in ‘Ravensdale’, and I have become equally fond of that pugilistic, caddish musical virtuoso Harley Venn and the down-to-earth Clarinda in ‘The Villainous Viscount Or the Curse of the Venns’. In ‘Alex Sager’s Demon’ I was also particularly fond of the haughty Ivan Ostrowski, and I had a lot of sympathy for Natalie Nicholson, who wanted to be a successful modern model, not the love object of a man from Tsarist Russia.

Still, writing of those absurdly over-the-top goings on in the North Wales of the time of the French Revolutionary Wars was the greatest fun of all, maybe because then I was a novice author, and those characters were so vivid to me, they at times almost took over the writing.

There was the pure incongruity of those two eighteenth century scoundrels caught up in occult happenings. Then there was their larger than life aspect: many historical romances feature a hero who is a highwayman, or a smuggler. I decided to go for the full hit and put both on Émile and Georges’s CV. That was besides their experience as the eighteenth-century equivalent of protection racketeers in Paris: and it is when he is in this guise that Sophie meets ‘Monsieur Gilles’.

And then, I loved writing about the creepy (in all senses of the word) dirty minded, gossiping, giggling Goronwy Kenrick, who somehow manages to be self-righteous about ‘that French ruffian’s’ criminal history.

Yet, the unlovable Kenrick has his tragic element; just as Émile longs for reunion with his dead siblings, so does Kenrick yearn for reunion with the one human being he has ever loved – his late wife. That is why it was finally written as dark comedy.

The original winning this award inspires me to return to writing the sequel with renewed vigour.

‘That Scoundrel Emile Dubois’ is available on

November 3, 2016

The Mary Sue: What Exactly Makes a Female Character a Mary Sue?

‘Which of you dared to call me a Mary Sue?’

‘Which of you dared to call me a Mary Sue?’

A couple of years ago I read a story by an author (traditionally published) whom I generally admire.

This story was fast moving, with a well thought out, tightly constructed plot; the heroine was independent minded, and never relied on a man to sort out her problems; the characters were vivid; the writing was strong; the background research was admirable but not obtrusive; there was humour; the grammar was excellent –and I ploughed through it.

What was wrong?

It did in fact, take me two days to work it out (quick on the uptake, or what?)

I thought then that the heroine was probably a Mary Sue, according to the definition of it that I had read- ie, that everyone admired her looks, character, moral stance, wit, etc.

But thinking about it recently, I am not even sure of that – because there seems to be some disagreement about what exactly a real Mary Sue is. A real Mary Sue has traits that seem to go beyond being accompanied everywhere by this chorus of admiration.

This is the Wickipedia definition:

A Mary Sue is an idealized and seemingly perfect character, a young or low-rank person who saves the day through unrealistic abilities. Often this character is recognized as an insert or wish-fulfillment.[] Sometimes the name is reserved only for women, and male Sues are called “Gary Stus” or “Marty Stus”; but more often the name is used for both sexes of offenders.

It seems it isn’t just that an unending chorus of admiration and too easily won devotion that makes for a Mary Sue, but fate working to clear her path miraculously of obstacles. I can’t say that was true of this particular female lead.

According to this definition, Fanny Burney’s Evelina and Samuel Richardson’s Pamela seem to me more like stereotypical Mary Sue’s.

While they do make ineffectual efforts to sort out their problems, they are too timid and feminine to do so properly, and these problems miraculously disappear when the hero proposes and so raises their social status.

While they do make ineffectual efforts to sort out their problems, they are too timid and feminine to do so properly, and these problems miraculously disappear when the hero proposes and so raises their social status.

Also, both heroines are singled out originally for special treatment by other characters so that they are placed to meet the male leads. Orville and the anti-hero Mr B do at quickly single out the heroine for special treatment too, and continue to pursue her determindly in the face of discouragement in a decidedly unrealistic way, indicating that the author is removing normal obstacles from the character’s path to social recognition.

In this, they are far more passive than the strong female lead in that other book. Though she had some special abilities given to her, she did have plenty of obstacles put in her way, and she tackled them bravely. She had none of the timidity of Pamela and Evelina. That was not a fault in the structure of the story.

So why did I feel so indifferent to the fate of this heroine, who if she did have a fault, was too impulsively brave and independent minded?

I think it comes back to that admiration from the other characters. I find too much of that can even make you feel that with all that admiration going about, the protagonist doesn’t need any from the reader. .

Whereas, if that recent heroine had shown exactly the same characteristics, and not received a fair amount of acknowledgement for them, that would have brought me determinedly in on to her side.

I did wonder, given that this was a well known writer, why there no editors or Beta readers to point out that a character who makes a fool of herself now and then, and who looks less than her best occasionally and who fails to impress someone or other now and then, is likely to be that much more sympathetic?

I did ask myself too, the Influenced By Sexism question – whether I would have found this female lead so tiresome if she had been a male character – and the answer was that I would probably have found her even more annoying.

Wickipedia also gives a definition of the male Mary Sue, and I think I have come across him rather more often:

Marty Stu or Gary Stu is a male variant on this trope, which shares the same wish-fulfillment aspect but tends to describe a character with traits identified as stereotypically male.

But this post is long enough already. I’ll do some research on male ‘Mary Sues’ or Marty Stus next.

However, this definition still seems a rather unsatisfactory one of a trope that authors go in such dread of following, that they feel actual horror at the thought of it being applied to their own heroine. Besides, the Wickipedia article concentrates largely on a discussion of fan fiction and Star Trek, I assume because it was through a spoof on this that the term originally came into being.

So, I went looking for other, more detailed definitions of the Mary Sue, confining this at the moment to female characters.

This blog gave an excellent analysis of the way that the Mary Sue permeates all our consciousness, and how to avoid her warping our works:

fmwriters.com/Visionback/Issue30/mary...

A Mary Sue is a character that the author identifies with so strongly that the story is warped by it. Sometimes male Sues are called “Gary Stus,” but more often the name is used for both sexes of offenders. The term was coined in fanfiction, made its way from there into the publishing world, and has slowly been filtering into the writing community as a useful shorthand for a frighteningly common error in characterization.

Along the way the definition of a Mary Sue has become muddied. For some, it is any self-insertion of the writer; for others it is when the character is obviously acting as wish-fulfillment for the writer. Sometimes it is a character who is excessively stylish or romantic or over-traumatized, or who never does anything wrong.

But these are all symptoms of the same literary crime: a character who, by the writer’s obsession with her, subverts the truth and power of the story. Mary Sue fights to appear in all our stories. She is the story equivalent of the spoilt brat who always gets her way, with the writer-parent running before her anxiously smoothing her path; she is lovable to no one but that parent. Mary Sues sometimes appear in valid works of fiction, but more often they render the story unreadable, a source of satisfaction to the writer alone. Spotting her and learning to discipline her is as important for writers as it is for parents.

Then, this blog, while it is largely about writing fan fiction, is useful for all writers on the topic of Mary Sues:

www.springhole.net/writing/mary-sue-subtypes.htm#fbnr-sue

Interestingly, a character being a Mary Sue does not mean that book will be a failure. After all, Bella Swan of ‘Twilight’ is very often defined as the archtypical Mary Sue. And who wouldn’t be happy with that level of success and public recognition?

Here is a very funny blog, the hall of ‘The Mary Sue Hall of Fame’

http://themostperfectblogever.tumblr.com/search/Bella+Swan