E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 18

October 4, 2013

The Colorful Dark Ages

One of the difficulties in writing historical fiction is to portray that time and place as it was, instead of relying on the images of things that remain, or, worse yet, catering to the expectations of those who think they know. We have an impression of the Middle Ages as dark, gloomy, shadowed. Certainly, it was all of those things, but it was also vivid, joyous and, quite simply, colorful.

Medieval architecture is an excellent case in point. The surviving examples of the period are primarily stone buildings (castles and churches) in shades of gray and occasional half-timbered houses, almost always white with dark timbers, with white plastered interiors. The reality of the time was quite different. We of the modern day must re-envision most of those plain white and gray surfaces being richly painted with bright hues that transformed every space into an artwork.

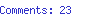

Saints and angels crowd Pope Clement VI’s chapel in the Papal Palace at Avignon.

House interiors featured wall paintings, often floor to ceiling, often even upon the roof beams. For modest homes, these paintings might consist of repeated patterns of lozenges (diamonds) or other simple geometric forms. As the homeowner grows in wealth and status, the murals featured coats-of-arms and heraldic devices, scenes of gardens, forests, tournaments and hunts.

And all of those stately churches, rife with sculpture and soaring arches? Painted. Almost every inch, even the sculptures. Nowadays, we view the sculpted elements as artworks unto themselves, the work of master carvers, which they certainly are–but to the viewer of the Middle Ages, the stone was just the beginning. To step inside a church, especially those of the twelfth century, after the advent of the flying buttress allowed for thin walls pierced by high stained glass windows, was to enter an artwork, a complete experience surrounding the viewer with the glory of God (or at least, with the wealth and power of the Medieval Church).

The idea startles our sensibilities, formed during the Victorian era of tourism and collection, which tend to favor the “purity” of marble, based on an ideal of sculpted houses of worship attributed to those refined and elegant taste-makers, the Greeks. Who, yes, indeed, painted everything. The Elgin marbles? painted. The Parthenon in glorious technicolor.

So far as we know, the great sculptors of the Renaissance–Michelangelo, DaVinci–did not paint their works, perhaps to create a break with the now denigrated past they were leaving behind. Perhaps in today’s world, when we are bombarded constantly with vivid images in advertising, billboards on the highways and even televisions at gas stations and dental offices, we need to imagine early architecture as a place of serene neutral tones, but to the citizen of Medieval England, the idea of confining art to a square upon the wall likely would feel just as unnatural.

September 26, 2013

Review: Hereward the Wake, ‘Last of the English’

Hereward the Wake, ‘Last of the English’ by Charles Kingsley

My rating: 5 of 5 stars

A marvelous adventure story with a medieval setting about the legendary hero of England.

I picked up the new Audible edition, read by the brilliant local storyteller Sebastian Lockwood, himself from the region where Hereward took action just after the Norman Conquest in 1066. Lockwood is a great narrator, who adds just enough vocal variation to the characters and uses his expressive voice to enhance the narrative.

Hereward is the son of the famous Lady Godiva (yes, that one) who is outlawed after he steals silver from a churchman, a deed which will come back to haunt him throughout his life. He goes from the home of one obscure relative to another, living for a time in Scotland, and having numerous adventures like slaying a polar bear (part of a lord’s menagerie) and rescuing a princess from a tyrannical suitor to send her to her betrothed.

Accompanied by the stalwart and somewhat insane Martin Lightfoot, he winds up in Flanders where he grows into a bold and revered captain of soldiers, and falls in love with the beautiful Tolfrida, who becomes his wife and companion through many later adventures. In 1070, they return to England to foment rebellion against the French invaders, on behalf of the Swedish king who has a claim to the English throne through King Canute (now there’s an alternate history it would be interesting to write).

This book is a delight of rich language, heroic deeds and tangled loyalties. It is written very much in the spirit of the legends of Arthur and other great heroes, mingling the historical truth of Hereward’s activities with smaller quests involving mysterious ladies, powerful giants, and saintly interventions.

However, this is the story of three clashing cultures. Three? Yes, because at the time, the north-central section of England where Hereward and his followers live and make their stand identified strongly with the Danes (this is the period of the Danelaw, a sort of culture-within-a-kingdom of former Vikings and their descendents). Many of their oaths and visions of the afterlife involve Odin and Valhalla, as often as they involve St. Peter or a Christian heaven. Their honor and morality is somewhat different to that of the Anglo-Saxon population.

When William the Conqueror comes from Normandy to press his claim to the throne, the divisions between these cultures of Britain must be erased in order to present a united defense. And we all know what happened there. Hastings, anyone? Hence the residents of the Danelaw supporting a Scandinavian king while those in Northumbria have already put forward a different candidate. Three kings, of three cultures, each trying to win over a people as yet uncertain of their shared identity.

And so, Hereward the Wake is at once a thrilling Chanson de Geste, or song of deeds, which even makes reference to the “Song of Roland” and those of other great knights, and an exploration of the uneasy blending of the occupants of a place before it truly becomes a single nation.

September 18, 2013

Brain-biter and Bansh: On the Naming of Things

I’m currently listening to Hereward the Wake, a historical novel twice over (one set in a historical period, and written, from our perspective, in a different one). Our hero has just won his sword, in grand Viking tradition, by slaying its former owner after the disputed princess has hidden the sword, a famous blade said never to miss, called “Brain-biter.” There’s a nice image for you. And it got me thinking about how we signal priority by what we name.

A noble steed named Aramis, after a character in The Three Musketeers.

The naming of things accords them a sort of respect not always due to the unnamed equivalents. Names indicate the dignity of the individual, and, in many cultures, are accorded power in and of themselves. Hence stories in which the hero will not reveal his name for fear it be used against him, and those in which people are stripped of their names as a way to prove power over them. The giving of names is an important ritual of birth or coming-of-age, and entry into religious orders, or the conferring of knighthood or a royal crown may be sealed by the addition of a name, or the use of new name entirely. So to name a thing is to give it honor and to welcome it into the life of the clan, the party, the history of man.

The concept of the famous sword goes back centuries. Possibly the most famous of named swords is Excalibur, the legendary blade of King Arthur of Britain. The northern epic tradition includes a number of such swords, partnered with great warriors–a tradition carried on in many fantasy novels that arise from that root. In The Hobbit, Gandalf and Thorin adopt swords from Gondolin, which come with names of their own (“Foe-hammer” and “Goblin-cleaver”), and Bilbo imitates this grand legacy by dubbing his own short blade, “Sting.” Sting goes on to carry out the duties of a warrior’s weapon, smiting great foes and referred to thereafter by its name, as if it were a character in its own right. Samurai narratives also include such famous blades, entitled to their own name and history. The names are often, like “Brain-biter,” intended to suggest the might of the bearer, but a named weapon also carries its own set of stories, which may, in fact, be separate from the life of any one bearer.

The other example in my title is the name of a horse, from Elizabeth Bear’s Range of Ghosts, an epic fantasy in the Mongolian tradition. In that realm of steppes warfare and hard winters, a man’s horse is often his closest companion, and horses serve as the second lead in many a tale of Mongolian exploits, so I was pleased to see Bear paying homage in this particular way. However, the translation of the horse’s name, Bansh, is “dumpling,” hardly the moniker of a noble steed. The more the horse proves herself in various adventures, the more those around them question this unusual and somewhat undignified name. Bear both honors the tradition of the named steed and pokes fun at the same time.

The authors out there will know, and the readers will understand, that to name a character in a book is to endow that person with a life beyond obscurity. The individual is thus distinguished from a crowd, whether it is a crowd of unwashed masses, an armory of ordinary weapons, or a herd of horses. Names are powerful, especially when we gift them to those who lack the voice to claim their own.

September 5, 2013

You’re in the Army Now

On my drive from New Hampshire to Atlanta for Dragon*Con, I had the opportunity to stop off in Carlisle, Pennsylvania to visit the Army Heritage Education Center, or AHEC. The AHEC has a very nicely designed museum indoors, and a fascinating heritage trail outdoors, featuring a number of restored tanks and armaments, a few helicopters, and some useful informational signs.

Being a history buff, my favorite is Redoubt #10, a reproduction of a defensive installation from the British side, during the Battle of Yorktown during the Revolutionary War.

A reproduction British bronze mortar of the Revolutionary War period.

However, I think the primary value of the site is to enable the visitor to try to enter into the circumstances of the average soldier. The AHEC does a good job, in my opinion, of honoring the soldiers as the people who are charged with carrying out the needs of their government, without glorifying warfare in general. A highlight of the museum portion is the Viet Nam nightwatch hut, where you sit in the dark, watching through a narrow window, and listening to a surround-sound recording of a few guys on watch, complaining about the crackers, wondering about what might happen–and responding with fear and courage as the enemy pours over the ridge nearby.

Part of the writer’s job is to convey experiences like this to those who have never had them: to create or re-create the moment. We seek to build the layers of sensory input–the hard seats, the darkness, the voices, the occasional spit of light–to bring the reader into a scene. Then we use those layers to build tension. Those lights–are they the enemy? No, false alarm–wait! Did you see that? We use our words to surround the reader and entice him or her to imagine the scene so fully that he or she is inhabiting it.

If we do our job well, the reader gains an understanding of what it would be like to be there, sharing that experience with worthy comrades, regardless of whether the enemy they confront is zombie, orc or human. We look for the universal elements of the situations we portray that our readers can relate to, then we add the more striking or unique elements to make the literary world complete. Because one of the underlying themes of the AHEC is that the soldier is still–from the Revolution to Iraq–at the heart of the army, and as one who writes about war, I hope that I, too, can honor that commitment and convey it to a new audience.

August 28, 2013

The Tangle of Medieval Medical Thought

Now that Elisha Barber is out in the open, available in a bookstore near you, one of the questions I’m frequently asked is whether I have a medical background. The short answer is, alas, no–though I am fortunate to have two editors with medical families, and the services of medical adviser, D. T. Friedman, to check out my surgical scenes.

A view of a reproduction Barber-surgeon’s chest shows tools both practical and not.

So, the follow-up goes, how did you become interested in medieval medicine? I’ve spoken before about the research rabbit-hole–this blog is primarily an ode to the research rabbit-hole, in fact: an opportunity to learn more about strange and interesting history, and to share the bits of research that excite me. In fact, after reading a little about historical medicine, my question is usually how anyone could *not* be fascinated by this stuff.

Science has changed a lot in the last several hundred years. Politics have changed (not as much as we’d like, sometimes). Nations have changed–often changed hands, changed religions, changed sides as well. Our lifestyles have certainly changed since the Middle Ages. But our bodies remain the same. They form a point of sympathy with people throughout known history, and even beyond. When we view a mummy with a wooden replacement toe, we can wince in sympathy at the idea of losing a toe and we can imagine the pain and the awkwardness of the prosthetic. Perhaps we can also imagine the utility of it–how this innovation made walking, wearing sandals–dare I suggest dancing?–that much easier.

The human body, the pain and problems it undergoes, and the desire to alleviate those pains form a parallax of understanding. They are also, from a literary perspective, a rich ground for stories. A story involving bodily trauma can create sympathetic winces in the reader (a power to be used carefully). One in which the stakes are high, vivid, and instantly relatable can draw the reader in and give him or her a strong rooting interest for the character.

And the desire to help, to fix, to cure–that urge toward healing others that underlies the medical profession remains a constant. At times, it moves more toward religion with the idea that cures come from a deity whose intervention must be sought. It moves toward superstition with the idea that illness is caused by outside, malevolent forces which might be manipulated by one’s enemies. And it manifests in a drive to truly understand the body, to pass on knowledge through books and universities, through apprenticeships and deliberate experimentation.

The medieval period covers an interesting, and often disturbing, conjunction of these manifestations of the healing urge. The Catholic Church preached for prayer and the intervention of saints related to the cause of the suffering. At the same time, it often forbade anatomical study as a violation of God’s creation. And yet, universities–many of them Church-sponsored–sprang up across Europe, offering medical instruction that was well-meaning, if often (to our eyes) bizarre. Hospitals were founded, and healthcare offered through charity, and medical treatises spread from hand to hand as practitioners developed new treatments and theories. Witches were accused of bringing illness upon their neighbors–while scholars and physicians blamed the plague upon the interactions of stars and planets, as observed by the science of the day.

This web of tensions strains and snaps and pushes medical practice from then to now. And it makes for powerful stories.

August 22, 2013

Meanwhile, Back in 14th Century Egypt

Like many American and European historical enthusiasts, especially those brought into the Medieval fold by way of fantasy literature, my immediate focus tends to be on the history of Europe. We love the castles, the kings, the knights, the tales of Robin Hood and Arthur. As a research area, this Eurocentric approach also makes things much easier because I can always find books about the stuff I need to know. (Even within the Euro-centric universe, there are blind spots: like the impression you’d get from looking at bookshelves that Rome and Naples virtually didn’t exist during the Middle Ages, ’cause they’re apparently much less interesting than Florence and Venice–Ha! But that’s another blog for another day.)

I am always intrigued, however, when I stumble upon a reference to my period in a different part of the world. I’m fascinated by the Anasazi ruins of the Southwest that are contemporaneous with the great Cathedrals of Europe, for instance. Today, it was a reference in a Wall Street Journal article about the destruction of the ancient Virgin Mary Church in Egypt. This is a moment linking the events of today–political upheaval–with those of history, and the kind of tragedy I find rather chilling because it proves the historian’s maxim about being condemned to repeat the history we forget.

So, the WSJ tells us this was part of “the largest attack on Coptic houses of worship since 1321.” And immediately, I want to know, what happened in 1321?

You’ll notice if you followed the traditional course of social studies classes in the American public school system that certain places are associated almost exclusively with certain times. So children study the Egypt of a few thousand years ago–and know practically nothing about what’s happened since. We’re left with an impression of people in skirts, with the heads of animals, writing on papyrus while the rest of the world has moved on to ipads. Of course, this is nonsense, but it takes an Arab Spring to pierce the average American’s obliviousness to the rest of the world. Even then, they are probably picturing Horus learning to tweet.

Back in 642, the Arabs completed a conquest of Egypt, but were content to rule from their own power bases, strongly suggesting conversion of the local Coptic Christians to Islam, but not pushing too hard (as long as taxes were paid on time, of course). This paper suggests that the monasteries became suspect because many poor farmers, trying to flee taxation, ran to the monasteries–already wealthy because of their own land ownership. The author gives a nice description of the relationships between various factions in Egypt for the next few centuries, including a period of rising persecution around the turn of the first millennium in which Christians were forced to wear distinguishing clothing and overt religious symbols (sound familiar? Yeah.)

In the 13th century, the region was also dealing with the external forces of the Crusades, and became increasingly drawn into line, with the Copts more fully embracing the Arabic language, even for Christian writings. By this time, the Copts are an affluent class of middlemen, undertaking the administration (including those pesky taxes), and succeeding waves of Islamic rulers, along with the growing Muslim population at the bottom became increasingly unhappy–as we so often do with those who seem to have privilege we’d like to claim, or those who seem to rise at the expense of others.

This growing unrest on behalf of the lower classes pressured the rulers to order the closure of churches, but it wasn’t enough, and the pressure exploded in 1321 into a rash of mob attacks against the Coptic churches leading to the destruction of up to 60 churches.

And now, the modern-day counterparts of those angry medieval mobs have destroyed some of the few remaining Coptic structures, including the Virgin Mary Church, which was estimated to be 1600 years old. I have no problem with people desiring self-determination–but I wish the transition could be peaceful, both for the sake of those people–dissenters and agitators alike–and for the sake of their irreplaceable shared heritage, a heritage the rest of the world often discovers only when it is forever lost.

August 9, 2013

Review: Sword of the Ronin

Sword of the Ronin by Travis Heermann

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

A rich, engaging, morally complex historical fantasy, deeply embedded in Japanese culture.

This is the second novel in a series, but I must tell you up front that I had not read the first. I supported the kickstarter project that launched the book, and recieved the ebook as a reward.

At first, it took me a little while to sink into this book. Something about the style was unsettling. . .and it occurred to me that the book reads like a translation from the Japanese. The syntax is just a little different, the passages of poetry or other Japanese works that open each chapter often flow naturally into the style of the narrative itself, a fascinating phenomenon, and one that speaks well for Heermann’s linguistic ear. The author lived in Japan for several years.

So, on to the story. We meet young ronin Ken’ishi working as a constable in a small fishing village, defending the week, denying the child of the former prostitute whom he saved from the life, even as he enjoys the company of both mother and child.

Ken’ishi’s choices–including how he treats this family that might or might not be his–were often unsettling as well. Once, I nearly set it down again, but when I read on past the moment that rankled, I found Ken’ishi the stronger for it.

His mindset and the world he lives in are decidedly non-Western, and the reader expecting a more straightforward fantasy narrative might be surprised by some of the turns, but the book rewards the curious reader with moving relationships, visceral battle scenes, and all the marvels of Japanese mythology.

Not for the faint of heart, Sword of the Ronin balances action with more intimate drama as both reader and hero question the way forward, and move through a landscape of war and legends to just the right moment of balance before the third volume. I, for one, will be looking forward to it.

July 31, 2013

What’s it Worth to You? How Comic-con Reaffirmed my Priorities

Comic-Con was a blast–full of all the wonder, insanity and delight of fandom everywhere–and it gave me an unexpected chance to consider my time.

Me, in barber-surgeon regalia, with a Viking, courtesy of the History Channel Vikings display at San Diego Comic-Con

Before I went to San Diego last week for Comic-con (my first ever), I had been warned about the lines. Still, it wasn’t until I was actually there, with about a hundred and thirty thousand of my closest friends, that I really grasped the reality of the lines. There are lines at SDCC to get free things from vendors, and lines to get into certain popular panels. There are lines to get a bracelet which will let you stand in line again in order to get an autograph from George R. R. Martin, a thing I accomplished at a local convention with hardly any line at all.

I did admire how they managed the lines: volunteers with signs not only help you work out where to stand, but also find the end of the line, while others will hold back the traffic in the hall so that your line can move through in an orderly fashion. The good people of SDCC know about lines, and they handle them with all the grace possible.

But it made me wonder. . .I think a number of people stood in line simply because there *was* a line–especially in the dealers’ room–even if they didn’t know what the line would lead to. Surely there was something good at the end! But what, exactly, constitutes “good”? How much of your time is that inexpensive, disposable item really worth? I’m willing to bet most of the folks in the lines never really thought about it.

I went to SDCC intending to wait for access to one of the big panels in Hall H, which seats 6500 people. I thought I might wait a couple of hours for that–it would be fun to be present, it would make my SDCC experience complete. I do, in general, feel that experiences are worth paying for, and that shared experiences are one of the things that make conventions fun. But when I got out of my previous panel, and looked at the reality of the line, I decided not to join it. Instead, I had some fabulous crab cakes, saw a 3-D movie preview, and chatted with a family of cosplayers. I later met a couple who had waited in that very line, for that very panel, for six hours. They got to the front of the line, but they never got in.

Six hours. . .

I could read a pretty long book in that time. I could draft a short story, or a couple of chapters of a novel. I could watch three movies, hike twelve miles (more or less, depending on the rate of ascent and the altitude), write a few blog entries (more or less, depending on research), write a couple of articles likely to pay a couple hundred dollars. . .

Six hours is a treasure. I’d love to have six spare hours to spend any way I’d like. Would that couple have felt good about the trade-off if they had made it inside the sacred chamber? How much of their life would it be worth? What would you do, if someone gave you that gift of time?

Time is one of the most precious things we have, and it’s a thing we can never get back. I’m glad I took the time to go to Comic-Con. . . and very glad I didn’t spend my limited time there waiting in line.

July 18, 2013

Healing Blood in the Middle Ages

So yesterday morning I was lounging around, watching my blood come and go, and wondering what to blog about. . . I was visiting my favorite vampires down at the Red Cross Donation Center, where I donate platelets and plasma about once a month (my vampires are very particular).

One of the taglines I use for Elisha Barber is: When bleeding was a way to heal, and magic, a way to die. But of course, bleeding is still a way to heal, hundreds of years later–except that, instead of removing the blood from the patient and discarding it, we remove it from a well person and transfer it to someone in need.

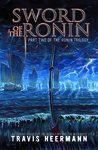

A bloodletting chart from 1493

The idea of bleeding patients began even before Galen, with the idea that health and personality were ruled by the four humors (Blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile), and that an imbalance–usually an excess of one humor over the others–resulted in a wide variety of maladies. Such an imbalance was corrected by bleeding the patient to draw off the surfeit by carrying it away with the blood (if the blood itself were not the problem). Elaborate charts and diagrams showed which body part to bleed from, depending upon the diagnosis, the astrological sign of the patient and the current astrological interpretation, as well as how much blood to draw. This chart is a bit later than my period, but it’s so pleasantly grotesque.

But this was not the only way that blood could heal. My local Red Cross Center is quite close to the Precious Blood Monastery. It’s worth clicking that link just to see the animated fountain of blood at the top. The Sisters use as their symbol of devotion the blood of Christ, as in the Eucharist. Interestingly, during my period, while the Host and the communion wine were both elevated during the Mass, it was only the priest, because of his particular status, who partook of the wine.

Those of us further removed from the Catholic faith are often a bit disturbed by such graphic images and references to the bodily fluids and remains of the revered dead. The Church maintains an uneasy relationship with relics today, and must go to some lengths to remind worshipers that the relic is only the symbol, and not in itself an object of worship. Shortly after the murder of Thomas a Beckett in Canterbury Cathedral, people were already dipping cloths (some torn from the Archbishop’s own clothing) in the pool of blood, preserving for themselves a bit of the holy man’s influence. Water said to contain a diluted bit of this blood was often taken in small lead phials for luck and blessing after a pilgrimage to Canterbury.

One of my favorite blood-related reverences occurs at the church of San Gennaro, patron saint of Naples. A miraculous bottle of the saint’s blood turns liquid three times a year, including on the anniversary of his martyrdom–back in the reign of Diocletian (maybe around 305 CE). This celebration has drawn pilgrims since 1389. According to local legend, great woe shall befall the city if the blood remains solid. A sort of spiritual prophylactic. Interestingly, there are a number of other saints–all local to that area of Italy–whose blood relics have the same property.

So really, with my personal bloodletting, I was participating in rite with a long, curious history–only the latest in the uses of blood to heal.

July 10, 2013

Studying Magic in the Middle Ages

One of the frustrations of being a fantasy writer is confronting the accusation that one can simply make it all up. The best authors, IMHO, use a combination of reality and imagination to bring a new world to life. To me, part of the fun in fiction is to blend invention and reality into an engaging and realistic experience for the reader.

My adventures in writing Elisha Barber began with research. Researching medieval medicine, and surgery in particular; researching 14th century England; and researching medieval magic. That’s the one that gets me the strangest looks, especially in bookstores. I’m not looking for books about Wicca or magical thinking, I’d have to explain, I’m looking for books on the history and study of magic.

Writing historical fantasy has its own attractions and difficulties, and this, it turns out, was one of them. As I became invested in the historical setting, I wanted to learn more about how my characters would have thought and reacted. What did they expect of magic? What role did it play for them, individually and in society?

One of the biggest surprises was the relationship of magic and the Catholic church. Many people believe the church always condemned magical practice and persecuted those accused of it. As I often discovered when I drilled deeper into history, the situation was more complicated than that. Many clerics, including popes, worked with sanctioned magical practitioners and consulted astrologers on a regular basis—the understanding of God’s creation and his plan through the stars fell in and out of favor over the centuries.

The Holy Office of the Inquisition was founded to investigate claims of miracles, including the related questions of heresy and eventually witchcraft. In many cases early on, no torture or execution was necessary, just an admission that the accused had misunderstood church doctrine and a promise to do better. In 1258, Pope Alexander denied the request of some inquisitors to investigate sorcery unless there was also clear evidence of heresy.

Later in the Middle Ages, when concerns about heresy verged upon civil war based in religious disagreement (Cathars in France, Protestants vs. Catholics)–this investigatory function expanded and allowed for abuse, bequeathing us the image of the all-powerful church trying to crush all manner of folk beliefs and unholy influences.

In fact, the greatest persecutions—like the infamous Salem Witch Trials in the Massachusetts Bay Colony–often had less to do with a fear of magic or even with religious disputes than with political pressures about land ownership. For much of our history, land meant wealth, and the church, as custodian not only of the souls of men, but also as a landlord, and as an intermediary for other leaders, could not help but be involved.

A couple of interesting sources for studying the relationship between magic and the church are The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe by Valerie Flint and Antoinette Marie Pratt’s Attitude of the Catholic Church Toward Witchcraft and the Allied Practices of Sorcery and Magic, in which the author herself frets about the early and medieval church’s lack of condemnation toward magic as a whole, though she ultimately concludes that such practice should be avoided. Actual transcriptions of church and other writings pertaining to witchcraft are also available in compendia like Kors and Peters’ documentary history Witchcraft in Europe, 400-1700.

But religion isn’t the only source of information. The magical practitioners of the Middle Ages left us a wealth of detail about rituals, beliefs and practices, often in the form of treatises bound together with unrelated texts into the codexes which served as personal libraries at the time.

At the International Congress on Medieval Studies, I discovered Societas Magica—an academic organization for the study of magic during the Middle Ages—and its associated newsletter and publication series Magic in History, include translations of actual texts, discussions and comparisons by scholars working in the field. Every year, new texts come to light, offering further insight into how magic was approached by contemporaries, and a chance for the accidental scholar like myself to be inspired.