E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 14

September 23, 2014

Of Druids and Motorcycles

Today is the autumn equinox, when day and night are equal in length, at one time considered an event worthy of note. Certain groups still observe the occasion, notably, the druids of England. Their preferred venue is, of course, the grand-daddy of prehistoric observatories, Stonehenge.

Stonehenge, seen last Autumn.

These groups refer to themselves as Druids, and I did not realize until I read the Wall Street Journal’s coverage yesterday of a recent controversy (about which, more later) how many druid groups are active in England right now. The article mentions two (The Loyal Arthurian Warband Order, and the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids) along with an Archdruid of Stonehenge and Britain, and the Council of British Druid Orders. which lists sixteen member groups, and references a couple of others. These groups are seeking to reclaim a heritage of nature-based worship disrupted almost two millennia ago by the Roman invasion of England.

In general, so long as that worship does not impede the rights of others, I think people should be allowed to pursue whatever religion feels nearest their soul (or whatever conception thereof they might hold). I have a number of friends who are pagans of various ilks, but the one proclaimed druid I met locally did not leave a very positive impression as a spiritual person. Still, I was a bit surprised to find druid organizations proliferating to such a great degree. Perhaps the call to protect the environment in general has encouraged this growth, along with a feeling of connection to the land.

Most of the evidence we have for a history of druidism and the practices that might have been used comes from the Romans themselves, who were hardly an objective source (rather like citing inquisitorial documents to research the beliefs and practices of witches). During the 18th and 19th century, there was a vogue for revivals of old-time religion, and much of what is claimed on behalf of many neo-pagan religions is actually born from that enthusiasm, rather than from an earlier history of belief.

The other source we have, is, of course, the archaeological record. As you know, I’m very keen on material culture: the physical evidence of what people make and do, where they go, how they use what they had and the places they lived. Archaeologists are adding to our understanding of prehistoric Britain all the time. Both the English Heritage magazine and Smithsonian magazine included coverage this month of the recent ground-penetrating radar survey of the Stonehenge landscape.

Which brings me to the controversy mentioned earlier. It seems that Arthur Pendragon (yes, that’s his legal name) the leader of the Loyal Arthurian Warband, is aasserting the historical custom of his group to park their transportation on a dirt track near the Stonehenge circle itself when they visit or perform rituals there. In particular, Pendragon’s motorcyle. English Heritage has spent a good deal of time and money in the last few years building a new visitor’ center and car park, and getting a highway moved to better preserve the landscape, and the experience of the landscape for visitors. Pendragon accuses them of wanting the druids to use the carpark mainly so that English Heritage can get their five bob parking fee.

But if you look at the history of use, the archaeological evidence tells us that people using the circle did, in fact, park themselves (their houses and workshops) at a distance from the circle and walk there. So an argument can certainly be made that the present-day druids be willing to do the same thing. After all, it’s about the sacred landscape, right? The walk to the circle was likely part of the ritual for many years and some types of observances. But probably not for everything. Sometimes, in contemporary religious observance, you just want to pay a quick call and be on about your day. Still, as a non-religious visitor to Stonehenge, I certainly applaud the effort to restore the site to a more prehistoric impression, and allowing motorcycle parking adjacent to the circle would spoil it.

I propose that, just like many churches have special parking areas set aside for the celebrants, English Heritage should consider setting aside a few parking places for druids (possibly via a placard system, or simply by confirming plate numbers of registered celebrants) who would not have to pay the fee to visit their sacred space.

English Heritage makes money, sure. And what they do with that money is attempt to preserve the history of the nation for future generations, including the generations of druids that will hopefully follow upon this one. It seems to me that the preservation of the Stonehenge landscape is one goal that all of those groups could agree on.

September 12, 2014

40 Years of Rule-based Magic: Celebrating the Anniversary of Dungeons and Dragons

As many of you may know, this year we celebrate the 4oth anniversary of the Dungeons and Dragons Role-playing system. No doubt some of you readers have been players at one time or another, no doubt some of you have rolled your eyes at those who played, and maybe some of you still do.

Classic D&D roleplaying game

My father, who introduced me to The Lord of the Rings, and at whose door may be laid much of the blame for my becoming a fantasy novelist, also introduced the family to D&D. I quickly graduated to acting as the DM or Dungeon Master, devising wicked ways to torture my (player)characters, and the rest, as they say, is history–or maybe, historical fantasy.

Speaking of blame. . .D&D itself has been blamed for one of the facets of fantasy fiction, the idea of rule-based magic. Through the system of game, magic-user players could gain experience, rise in levels, and gain access to new spells, which would have certain effects based on the roll of the dice. D&D created a structure in which fantasy adventures could take place and the participants had an understanding of what to expect–the sphere of possibilities in the game, similar to establishing the contract with the reader at the start of a novel.

The contract with the reader basically draws some boundaries around the imaginary realm of the book by which some things are included and others are excluded. It can include the physical contents of the world (dragons or vampires) and the intent of the author (this is a book where blood and sex are present on the page–or not). It helps to ease the reader into that imaginary realm and allow him or her to experience the book at its best. If anything could happen–anything at all–it’s hard to know what to worry about or what to be excited about. Any new, random event is simply the next in a catalog of miracles without cause/effect, without influence by the characters, and beyond their ability to change.

Many of the early great works of fantasy do not appear to have rules for magic–the contract with the reader suggests that magic is mysterious, numinous, rare and valuable. Characters like Gandalf and Schmendrick–radically different in their nature–have access to a great and dangerous power, but use that power so sparingly that the characters must rely upon a variety of approaches to solving their fictional problems. The Wizard of Earthsea must learn and cultivate his magic–and discover that not all magic is to be deliberately taught.

Fast forward to the contemporary greats. One of the attractions of authors like Brandon Sanderson is his generation of a new system of magic for each of a dozen series. I’m not sure Tolkien would even have thought of magic as a “system,” yet that term is part of our writing lexicon, a thing that can be discussed as separate from worldbuilding or theme or character, elements that magic was once inextricably bound to. And it has been said that the influence of Dungeons and Dragons is a large part of the reason this is so.

Many current authors of fantasy, like myself, were players of D&D. I like to think being a game master helped me to develop plots and to tailor events to characters (in the form of my hapless friends). However, many of the readers of fantasy also began as players first of D&D, then of its many successor adventure games, all the way through Magic: The Gathering, which is fundamentally *about* the rules for magic. I’ve heard some authors and publishers sniff that gamers don’t read, which has not been my experience locally where many of my fans are both readers and gamers. Even if that were true, that doesn’t mean that readers don’t game–or that they never have.

I suspect that those experiences as gamers influence the reader’s side of the contract of a novel. Many readers now approach a fantasy world expecting that magic has a structure which can be discerned from viewing its influence on the narrative. Some authors make the system more explicit, as when Elisha, in my novel Elisha Barber, learns the confines of the application of magical power.

It can be argued that such constraints force the writer to be more creative, because he or she is constantly looking for startling ways to apply or defy them, and that they allow the reader greater enjoyment because they know exactly what to worry about, what to hope for, what to look for–like mystery readers seeking the clues in the race to find a killer, they enjoy trying to work through the puzzles of plot constraints.

What do you think? If a writer, were you a player? How has it influenced your approach to writing? If a reader, has gaming influenced your approach to reading?

#SFWA

August 12, 2014

Find me at Worldcon

This week, I’m in London to enjoy the annual World Science Fiction Convention (and to pay a visit to a working model of Su Sung’s astronomical clock, which happens to belong to the Museum of Science, London, but I digress).

If you’ve never been, you should know that Worldcon is a fabulous gathering of geeks from all over. Primarily, we are literary geeks, but there will also be film, video, anime, masquerade, art show, and a bunch of other nifty things.

If, on the other hand, you are already planning to attend, I’d love to meet you at my Kaffeeklatsch on Friday, August 15th at 6 pm. You will need to sign up in advance as specified.

I will also be part of a panel entitled “Doctors in Space” on Saturday from 1:30 to 3 pm, where we’ll be talking about the role of medical professionals in fantasy and science fiction.

I’ll also be riding the Eye, paying a call to Diagon Alley, then heading to the coast for some fossil hunting. Hope to see some of you there!

August 7, 2014

Frozen: World-building on Ice

I’m starting to see a series here on the blog about my thoughts on the world-building of various new films. Today’s subject is “Frozen,” a fun and surprisingly anti-Disney-trope Disney film. Not being real big on princesses, I wasn’t sure how I’d feel about this one, but it undermines a lot of the stuff that Disney Princess films are supposed to be all about, mainly that the love of a man and a woman is the only thing that makes the world go ’round.

In this case, the characters’ problems, and their solutions, come from within. It’s not the fear of some faceless mob that threatens Elsa–it is her own fear of herself. Likewise, it’s not the sacrifice of some other person that saves Anna, it is her willingness to sacrifice herself.

Okay, E. C., you liked the movie, so why are we here? We’re here for Kristoff. Kristoff, the reindeer-loving local boy, gets kinda short shrift in this film. Yes, he’s helpful in getting to the mountain to find Elsa, and yes, he brings Anna to the right people to help her out, then hurries her all the way home to her (presumed) savior. It’s a noble and a beautiful thing–though he doesn’t even get to be the one who saves the day. But there’s one aspect of Kristoff that gets neglected. He’s an ice merchant.

We first meet him as a small child at the feet of a group of men who are harvesting ice from mountain ponds to deliver to those in warmer climes. (As an aside, I am still fascinated by the idea that the same thing was done here in New England, where ice was harvested from local ponds and shipped, packed in straw to insulate it, all the way to India so the British could have cold drinks. But that’s another blog for another day.) Kristoff grows up surrounded by snow and ice, learning about it from his culture and from his labor, gaining the knowledge to work with it safely.

When he arrives at Elsa’s ice palace, he’s clearly impressed. So are we, but for the non-ice-initiated, it’s basically just a pretty (and cold) piece of architecture. At this point, Kristoff even tells us, “I know ice.” But what, exactly, does he know about it? We already know that his livelihood is in the tank–he’s an ice merchant during an eternal winter–so the conflict in the film is personal. From a narrative perspective, that’s great. It raises the stakes and gives him a personal investment in the solution, and it gives the viewer a rooting interest in him. Woo-hoo.

Unfortunately, that’s the last we ever hear of Kristoff’s ice-knowledge. Given the advertising images of the film which clearly suggest a relationship between Kristoff (ice merchant!) and Elsa (ice maker!) I suspect that his attachment to ice is there mainly as a red herring to throw the viewer off about where the story is going, and who will turn out to be a hero in the end.

Perhaps they wanted to throw in that little twist, making us believe that Kristoff and Elsa were perfect for each other until we find out the truth, but I am still a bit disappointed that Kristoff’s skill with ice is never plot-relevant. They’re living, for a while, in a world dominated by ice, yet he never comes through with any special insight. A way to attack the ice and snow beast? A safe route across the broken ice flows? A glimpse into the ice of Anna’s heart that helps him know what to do? Given how tightly crafted the rest of the film is (check out the timing of Hans’ glove removal) I wish they had taken just a little more time to bring out Kristoff’s knowledge of this world. That would have been (sorry, can’t help it) totally cool.

July 30, 2014

Guest Blog: The Love of a Dwarf

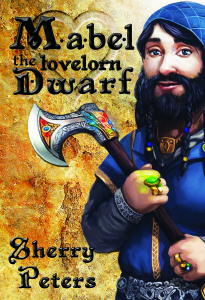

Today, I am hosting amazing Life Coach and fantasy author Sherry Peters, whose book, Mabel the Lovelorn Dwarf is about to publish in a e-format near you (check out the links at the end to read more). I asked her to share her take on the Dwarf/Elf romance angle of the recent Hobbit films. . .

Mabel the Lovelorn Dwarf proudly displays her courtship braids. . .

The Love of a Dwarf

When “The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug” hit theaters, many raved about Tauriel, the female elf warrior. Finally there was a female character who was a warrior. She’s strong, she goes after what she wants, she fights evil, and she’s true to herself.

Sadly, Tauriel couldn’t overcome the curse that is being a female elf. Which is to say, her stunning beauty meant everyone fell in love with her. We saw this in the Lord of the Rings when Gimli was mesmerized, infatuated even, with Galadriel. Arwen had the love of Aragorn, who, even when he thought Arwen had gone to the Grey Havens, couldn’t be swayed away from his love for her by the beauty and strength of Eowyn. Eowyn had all the strength and amazing character of Tauriel, so one would think she would be the obvious replacement for Arwen, but Eowyn wasn’t an elf. Had she been an elf, Aragorn would have at least had a difficult time deciding between the two.

While Galadriel and Arwen only had one guy hopelessly attracted to them (that we could see), Tauriel was doubly cursed: she had to contend with the love of both Legolas and Kili. In fairness, she did return Kili’s affection. And why wouldn’t she? Kili was the best looking of the party heading out to the Lonely Mountain. But what I want to know is why Kili is only interested in Tauriel? What about Legolas? He’s just as pretty, if not prettier, than Tauriel. As graceful, strong, and self-assured too. Or is he?

It seemed to me that Legolas was a little too eager to insult dwarves. He admited to Tauriel that Kili is taller than the others, but is “no less ugly.” He also called Gimli a horrid goblin mutant and suggested Gloin’s wife was a male. It wasn’t because he was confused by her beard, he was over-compensating, mesmerized by her, covering for the prolonged moment of looking, soaking in her attractiveness. His attraction to dwarves confused him and he didn’t know what to do with it so Legolas did what we all do when we’re too embarrassed to admit we like someone, we insult them. After all, it was only after he suggested Gloin’s was a male that his insults grew in offensiveness. Legolas joined Tauriel in fighting the orcs to save the dwarves because he wanted time to understand his attraction to them.

Here’s what I think: Legolas fell in love with Gloin’s wife. He had to hide it because as the son of the elven king, he could not love a dwarf. By the time of The Lord of the Rings, Legolas had years to grow into himself and understand his feelings for dwarves. Perhaps his father and his rank as elven prince had less control over him. Perhaps Legolas befriended Gimli because he wanted to use Gimli to get to his mother. It could have been that Gimli’s mother passed on so Legolas felt it was now safe to befriend her son. Regardless, Legolas now knew that dwarves were attractive and worthy of his love.

So where does this leave dwarf/elf relations? Are female elves going to have to relinquish their place as the inevitable love interest for all males, elf and dwarf alike? Somehow, I don’t think they’ll mind if they do. I’m sure most female elves, including Tauriel, want to be loved for their strength of character, not just their immortal beauty.

What about female dwarves? Will they now have a chance at being seen as attractive? Legolas took a brave first step in leading us all to the realization that while female elves are gorgeous and powerful, they aren’t the only ones who are loveable.

I, for one, look forward to the day when male elves and female dwarves are openly mesmerized and attracted to each other.

About Sherry Peters:

Sherry Peters attended the Odyssey Writing Workshop and holds an M.A. in Writing Popular Fiction from Seton Hill University. When she isn’t writing, she loves to have adventures of her own including spending a year working in Northern Ireland. Mabel the Lovelorn Dwarf is her first novel. For more information on Sherry, visit her website at http://www.dwarvenamazon.com.

Sherry on Facebook

Sherry on Twitter

Mabel the Lovelorn Dwarf on Amazon

Mabel on Barnes & Noble

Mabel on Kobo

Smashwords: http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/457271

July 17, 2014

Automata of the Middle Ages

This topic is one of the interesting intersections between my medieval research and my current research into Chinese technology. Some of the earliest known automated figures are clock jacks–figures that come out and do something when a clock strikes a certain hour. On Su Sung’s astronomical clock (c. 1070 CE) ranks of figures perform various actions at different times, including playing music. Designs for similar figures exist in The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices, produced c. 850 CE by a trio of Iranian brothers.

the bell-striking “Jacks” at Wells Cathedral clock dating to the late 14th century

These figures move by a series of gearworks tied to the mechanism of the clock, which might be driven by weights or by water (Su Sung). The handy thing about a water-driven mechanism is that the water can be made to do many other things, like fill or empty from a chamber resulting in slower or more complex movements, like the playing of music which often consisted of either percussion (made by the dropping of objects or lowering of an arm) or flute music, made by using water pressure to force air out of a narrowed opening creating whistles of different tones.

In England, in the 15th century, the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths organized a revel to honor the king which included a statue of a golden angel who turned and raised a trumpet. I have been trying to find my notes about this celebration without success–perhaps one of the scholars out there has the specifics? Automata of various sorts appear in the literature of the time, sometimes as mechanical arbiters of justice. Apparently, they begin to appear in the mid-12th century, suggesting that the European image of automata may have been influenced by real examples seen during the crusades as a result of the Islamic interest in such devices.

Automata had a darker role as well, however, one that suggests not their “ingenious” nature as created by man, but their unnatural aspect. The 13th century friar Roger Bacon, regarded nowadays as an early chemist and precursor to today’s scientists, is said to have possessed a brazen head that could speak prophecies–and which was presumed to be of demonic origin. He was imprisoned as a heretic, but eventually freed to die in obscurity and spawn much later speculation about the true nature of his talents.

For myself, I prophesy that I shall much more to say on this topic at a later date.

July 15, 2014

The Fiction Reboot Presents: “Striking Research Gold” by D.B. Jackson

[image error]E. C. Ambrose:

Here’s fellow historical fiction author D. B. Jackson talking about his research, in this case, into a smallpox outbreak in Colonial Boston. Seemed like just the kind of thing I should pass along. Enjoy!

[image error]Originally posted on Fiction Reboot | Daily Dose:

[image error]Welcome back to the Fiction Reboot and the Daily Dose! Today, we are pleased to present the work of D.B. Jackson/David Coe–the Thieftaker Chronicles. One of my favorite things about this series, aside from the brilliant characters, is Jackson’s use of history. I am a historian myself, and work at a medical museum–disease stalks our past like no other villain.[image error] (Of course, disease isn’t the only villain in the Thieftaker’s Boston!) Let’s hear about striking “research gold”–Welcome D.B.!

___________________________

[image error]My newest novel, A Plunder of Souls, is the third installment in my Thieftaker Chronicles, a series of historical urban fantasies. It should come as no surprise to anyone that the writing of these books, all of them set in pre-Revolutionary Boston, has required extensive research. I have consulted historical monographs and biographies, old newspaper articles and a host of other sources, some of them utterly predictable, and others…

View original 1,462 more words

[image error] [image error]

July 9, 2014

King Edward and the Jews

One of the characters in my books who has been very well-received is Mordecai, a surgeon who begins as an antagonist and turns into Elisha’s mentor. But his presence in this world at all needs a little explanation. . .you see, the books are set in 1347, but Edward Longshanks expelled the Jews from England in 1290.

Edward I is known, even renowned, for his prowess as a warrior and war-leader, a proper king in the medieval tradition. Then, as now, war was an expensive proposition, especially if you wanted to wage it on several fronts, say, in Scotland as well as pressing your claims against France. Where to get that money? Taxes are nice, but not always sufficient, and there is the bother of collecting them. How about a loan instead? During the Middle Ages, Christians were not allowed, by Church law, to collect interest on loans to other Christians, so this dubious role fell upon the Jews. Frequently merchants and skilled craftsmen, the Jews thus also became bankers for a large number of Christians, and, in a roundabout way, Christian monarchs.

Clifford’s Tower in York, site of a notorious massacre of Jews in 1190

William the Conqueror had established the feudal system of allegiances when he took over England, but the Jews were exempted, owing their allegiance directly to the crown. This was a relatively common arrangement and sometimes served to protect Jews from the anger of Christians because attacking them meant attacking the king. In Avignon, the popes served in a similar function, and sometimes used it to defend the Jews against the outlandish accusations that arose during difficult times, like the Great Mortality (the Black Death, as we know it). However, the Jews received interest from their Christian clients, and the king could selectively tax the Jews at a higher rate to seize that money for his own needs.

And here is the tragic heart of so much of that anger against the Jews. . .nobody likes the guy who holds the purse strings. Jews were decried for the very role that Church law pushed them into, that of usury. Among the many deep and deadly roots of antisemitism is simple economics. Medieval attitudes toward Jews still persist today–I’m not going to dignify them with enumeration.

In the case of King Edward I of England, his wars began to strain his finances. He wanted to raise taxes from his nobles, and essentially bargained away the Jews–expelling them from England, as he had during his earlier conquest of Gascony, and seizing their property–gaining wealth and gaining the favor of his subjects who resented the Jewish community.

While the Jews were not officially permitted to return to England until 1657, there is some evidence that they had begun filtering back. I imagine Mordecai to be one of these quiet, individual migrants. Under the burden of his own grief, Mordecai has ceased to be concerned about what happens to him–until Elisha’s example shows him another way to cope.

One of the reasons I wanted to write these books was the number of times, in my historical research, that I read of witches, Jews and homosexuals being treated together with heretics, and subjected to any number of injustices as a result. I wanted to look at the layers of prejudice built up in the society at the time–and perhaps to consider how those prejudices remain, even today. I am disturbed by the apparent rise in anti-Semitic crime and commentary–and by the fact that its roots lie in weary rumor and in doctrines laid out centuries before. Some parts of history are meant to be relegated to the scrap heap of time.

July 1, 2014

Elisha Magus Book Day! With footnotes. . .

Hello, all,

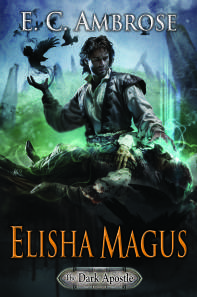

it’s the day I’ve been anticipating for at least a year–the release day for Elisha Magus, book 2 in my Dark Apostle series.

Cover of Elisha Magus, by amazing artist, Cliff Nielsen

In the past year, some of my blog entries have been of the sort I consider footnotes to the text–they talk about historical details or choices related to the book itself. For those of you who’d like to follow along, here are some of those links, so that you can insert these tidbits as you enjoy the text, or return here afterward to learn more about some of the settings in Elisha Magus. As you know, research is a large part of the fun for me–I can’t use everything I learn, but I’m often informed by it as I write.

The two death markers of William Rufus

Researching what blooms in an English medieval garden

The Traitor’s Gate (file this under “sirs not appearing in this book”)

Enjoy!

Myself, I will be sharing the book with my local audience at the Farmer’s Market here in town (dressed in my barber-surgeon outfit, complete with tools and bloody handprints–should be fun!).

You can also find me celebrating the book at the Toadstool Bookshop in Milford, NH on July 10 from 6 to 8 pm

and sharing the stage with the amazing Carol Berg at the Old Firehouse Bookshop in Fort Collins, CO on July 25th at 7 pm.

June 28, 2014

Stretching things out: Hanged, Drawn and Quartered

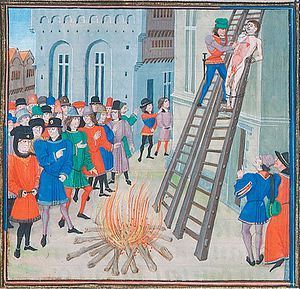

During the Middle Ages, execution was a big deal–usually a very public big deal, with citizens gathering from all around to witness the event, both as a celebration of justice (the king’s and therefore, the Lord’s) and a warning to others, as well as a social occasion, in the way that following an important trial might be today. The details of the crime may be horrifying, the “common interest” in the preservation of law and order is emphasized, and, well, it was a bloody good show. Tension, drama, high stakes. . .sometimes literally.

One artist’s conception of the execution of Hugh Despenser the Younger.

In England for many centuries, the official punishment for traitors was to be Hanged, Drawn and Quartered (sometimes with disemboweling thrown in for good measure, as in the executions of William Wallace or Hugh Despenser the Younger during the 14th century). It’s important to make a distinction between your ordinary hanging, and the sort practiced as part of a larger punishment scenario. Most hangings were meant to occur on a scaffold in which the victim would receive a large “drop”, often by pushing the individual over the edge of the platform. Done properly, and with a well-placed knot, this results in the neck breaking, with death following soon after. If the unfortunate soul did not break his neck right away, friends of family members might be permitted to rush forward and give a tug on his legs to ensure a quick death. Hence, “hanged by the neck until dead.”

In the longer version, the criminal would be lifted from the ground by the rope and suffer strangulation (more similar to what happens to Elisha in Elisha Barber), a more protracted death. If the victim is to undergo additional penalties, he would be cut down after a brief and terrifying interval, to await the next stage. In this case, either the disemboweling, or straight to to being drawn–limbs bound to four separate large animals who are driven in separate directions until the victim is torn, well, limb from limb, and thus, “quartered.”

For the traitor, the quarters are then sent to the four corners of the kingdom to serve as notice to any who might consider the same crime. The head is typically removed and retained separately, often for display on a spike on the Tower Bridge, if the execution has taken place in London proper. The heads could remain for a long time before disintegrating, or, occasionally, being smuggled down for burial by the supporters of the deceased.

When I’m reading or writing about stuff like this, after overcoming the initial impact, I start to wonder about the details, like who is responsible for dragging the quarters to their distant resting places? It is events like this, after all, which result in our fore-fathers banning of any “cruel and unusual punishments.” Cruel? Definitely. Sadly, not so unusual in the history of the world. Something to think about as we head into July 4th week. It’s clauses like that which make our nation worth celebrating.