E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 17

January 8, 2014

Review: The Inner City

The Inner City by Karen Heuler

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I had the pleasure of meeting Karen at my reading in New York in July. As on many such occasions, we swapped postcards with our respective book covers on them. This cover is interesting, but the blurb on the back of the card got my attention, the same blurb on the back of the book:

an employee finds that her hair has been stolen. . .strange fish fall from trees. . .birds talk too much

Authors take note: this may be the first time I have purchase a book because I got the post card. Those things do work!

The Inner City is a collection of short stories from this award-winning author. The stories are odd, quirky, sometimes horror, sometimes merely supernatural or strange, and several of them are downright unforgettable. I’m thinking of asking Karen if I can use a couple as campfire stories, when I’m sitting in the dark with a group of teenagers and I want them to get all round-eyed with dismay. That would be “Creating Cow.” Other mind-stickers include “The Escape Artist,” and the title story, about an office worker at a very strange office–yet one that will seem, to most of us, very familiar.

These are not the kind of stories that I would write. They have an almost fairy-tale quality to them, and many are drawn from that kind of source. They don’t build scenes and settings, rather they build psyches, characters and emotional contexts that are at once believable and unsettling. Creepy good stuff!

January 1, 2014

Dear Writers, Welcome the New Year with Change

Hey, it’s 2014! I have a lot to look forward to, like a royalty statement that will definitively answer the question, “How’s Elisha Barber doing?” And the release of Elisha Magus in July, which I’ll be sure to talk lots more about later. Also a visit to London for Loncon 3, the World Science Fiction Convention in August (with a stay in a castle, ’cause, why not?).

I hope many of you have some good stuff to look forward to as well. For most folks, the start of a new year is a time for reflection and resolutions. And I’d like to encourage the authors of my acquaintance to take “Change” as a theme for their work in the months ahead.

You see, as a reader (often as a critiquer of the works of writing buddies)I am becoming increasingly frustrated with a lack of change. So many of the stories I’ve been reading have no change from the beginning to the end. The protagonist remains unaffected by the events of the tale, the world is fundamentally the same at the end as it was at the beginning, even the reader, who, in the literary world, is meant to feel the change in their own perspective or understanding of the situation, is left unmoved by whatever has just occurred.

In many cases in these stories (some of them published, some of them not), there is, in fact, no character who has the ability to change the direction of the plot. Stuff happens to them, and they react to it in some small or ineffectual way, and remain as they were, perhaps victims of events, perhaps merely observers of them. To me, this is the most egregious lack of change–that wherein the character never, in fact, had the power to change themselves or anything else. Why would I want to invest my time reading about such people? I certainly wouldn’t want to write them.

Fantasy is often a genre of transformation, and most of these transformations take the small, weak or powerless and give them access to the power to change their world–and themselves and the reader along with it. That’s a story readers return to over and over, whether it takes place in Middle Earth, or Panem, or platform 9 3/4. That’s the kind of thing we love. We want to worry and wonder if the character will succeed, if the powerless can take on that strength, if the power itself will become a problem.

But wait, aha, you say (especially those of you with a more literary or contrary bent) what if the story is *about* the inability to change? To that I say, “Waiting for Godot.” There is occasionally a work which explore themes of stagnation in a different, unique and exciting way. Very occasionally, and I’m not sure the market can sustain a whole lot of them. I think many authors (especially those who are more literary or contrary) think they will cleverly undermine the tenets of genre literature by crafting a tale in which–Ha, ha!–there is no change, no transformation, no development of swineherd into king, no magic which can save them, no planet safe to settle on. Ooh. Big twist–nothing changes!

Yawn. Get over it. It’s not clever any more. This is where the idea of change for the reader is key. If you are desperate to explore a world in which change is not possible and characters will not progress to a new place, then ask what effect you want to create for the reader. Take Fahrenheit 451 versus 1984 Each is based in a totalitarian society that thrives by controlling information. Each features a protagonist who is sparked to consider change. In the first, he succeeds by becoming part of a movement, a group that may be able to change the world. In the second, he fails, smothered by the system. Y’all probably remember which one you preferred to read in school, am I right? But they’re both great books, and 1984 succeeds because the author wants the reader to be the carrier of change, to root for his characters, to fear for them, to feel frightened and wary when they fail–and thus to be more vigilant in his or her own life.

So, if you can, be the change–embody the values you want to inspire in others. If you’re a writer, write about that. And if you’ve just got to write the story of the status quo, then make it stick to the reader like a burr he can’t shake, so that it’s the reader who is inspired to make the change.

#SFWApro

December 23, 2013

Religious Influence on Medical Care, A Historical Perspective

A couple of recent court cases and the advent of recent changes to health insurance law have brought the issue of who controls the patient’s access to health care into the public mind, particularly in relation to religious freedom. Should religious organizations have to provide access to treatments of which they disapprove? How about businesses which happen to be owned by religious persons? Should religious pharmacists have to fill prescriptions for such treatments? Are Catholic hospitals bound to follow the Do No Resuscitate directives of patients who do not have access to other hospitals?

From the fourteenth century perspective, it says a great deal for the attitudes and values of our society that we can even have this conversation. Back then, Catholicism was more or less the official religion for most nations of Europe–so taken for granted that nobody had to write a document to say so. Minority religions were ignored, persecuted, despised or accepted depending on the regime in charge at any given time, and what they had to offer to that regime. And medical care was closely linked to religion, with treatments options often circumscribed by some interpretation of the Bible.

For instance, the idea that women should not be given access to pain-management drugs during childbirth because the Bible says they should give birth “in sorrow.” So if it doesn’t hurt, that’s in defiance of God. Yikes! At various times, opium for the control of pain was banned by order of the Pope, only to have the ban lifted by a later patriarch. That suggests some level of discomfort with the idea of encouraging suffering, yet at the same time, many future saints and beatified persons displayed great fortitude in the face of painful or disfiguring illness in a celebration of such holy suffering.

Illnesses were often taken as a sign of God’s disapproval, and treatments might be literally religious: patients often went on pilgrimage, made offerings at churches, hired priests to say masses or paid abbeys to pray. Bits of saints perceived as related to the ailment might be brought to effect a cure, the equivalent of “Say two ‘Hail Mary’s’ and call me in the morning.”

The physicians of the time were, in fact, often minor clergy, trained at medical schools established or managed by the Church itself and expected to comport themselves with that sort of decorum. How would you feel now if your doctor were not only affiliated with a Catholic hospital, but were actually a cleric himself who might well prescribe penance for your spiritual failings alongside a nice, healthy bleeding every couple of months?

Okay, that’s probably overstating my case. The physicians were, in some way, participants in the miracle of God’s creation, trained to understand certain aspects of His work and thus to look for the signs that God would allow a cure to take place. Or, as Ambroise Pare put it, “I stitched him, and God healed him,” suggesting that medicine and religion went together. Even if the doctor didn’t call upon a saint’s intervention, he still anticipated that God’s approval was the final ingredient to any cure.

At the same time, especially among practitioners who learned their trade through non-religious means, there was an increasing awareness of and interest in methods that really worked. Surgeons wrote manuals for one another, swapped recipes and cures and worked constantly in their own practice to improve technique and technology, without any apparent qualm that God disapproved of such efforts. Medicine finally shook off most of its religious influence after the Renaissance, especially with the advent of the Germ Theory, which found a direct cause for many previously mystifying (therefore likely heaven-imposed) illnesses.

There are still sects who believe that prayer alone is the cure–God will either heal you or not, it’s up to Him–but many more people who take a more practical approach. Given all the advances in medical science, maybe God, in fact, wants us to be healthy and pain-free. If you’re inclined to believe that God is at the root of everything, than that means he gave man not only the natural treatments that can be derived from the world around us (willowbark tea, anyone?) but also the intellect to devise even more.

Alas for the suffering people, so often, we turn that intellect to arguing against advances in medicine, to making complex systems that prevent access to healthcare, to generating labyrinthine billing methods that result in huge debt loads for patients, creating the impression that many are still advocating a right (if not a duty) to suffer. A fact that seems, well, positively medieval.

December 4, 2013

Why Things Sound Better in French

I was strolling through a gourmet food display recently, when a young companion asked why you don’t pronounce the “-t” at the end of the word, then observed that it must be French. She then went on to wonder why everything in French sounds fancier, and I realized that I might know the answer: William the Conquerer.

The gatehouse at Battle Abbey, built by William I of England to commemorate the dead of his victorious conquest.

William, the Norman duke (“Norman” is originally a contraction of “North man”, so we’re talking about transplanted Vikings at a great remove) came over to claim the crown of England from Harold in 1066. I’ve most recently talked about this in my review of Hereward the Wake, who was one of the rebels resisting the Normans–and supporting a Danish claimant, but that’s another story.

After his conquest, William set about to replace the remaining native nobility with his friends, leading to a whole variety of interesting complications for land ownership in both England and France, and the problem of a king of England who was technically a vassal of the king of France as well. Most of these new nobles and their households spoke primarily or exclusively French, and French remained the language of court for a couple hundred years. The Canterbury Tales (c. 1386) were in part remarkable because they were written in the vernacular–neither in Latin, the language of tradition and the church, nor in French, the language of court.

As a result, the English language expanded to include a wide variety of words borrowed from the French. French was the language of the upper class, a status to be coveted. Many of the words in common use are about food. If you’ve ever wondered why the animal is a pig in the yard, and pork on the table, this is the answer: pigs are raised by the lower classes, while pork is eaten by their betters. (likewise with beef, even leading to the term “beefeaters” to refer to those spiffy red-clad guards at the Tower of London–a term of derision and envy for an elevated place and the diet that came with it.)

It’s interesting that, while many words grow divorced from their origins in fairly short order, never mind the impression of a language in the mind, we in America, hundreds of years separated from our English origins and hundreds more from the initial infusion of French into the language, still perceive French as being somehow superior, to the point of devising faux-French names (and using the word “faux”), especially for restaurants. My personal favorite remains, from “L. A. Story,” the exorbitantly snobbish restaurant, “L’idiot,” pronounced, of course, with a silent “-t”.

November 20, 2013

Like you Need a Hole in the Head! a Defense of Trepanation

I recently wrote an article for Renaissance Magazine about the Brighter Side of Medieval Surgery, because, yes, there is one. If you’re not a subscriber, you can find the ‘zine at many bookstores, or on their website at http://www.renaissancemagazine.com/ But here, I’d like to take a closer look at one of the topics covered in more detail, that of trepanation, the practice of cutting a hole in the skull of the patient.

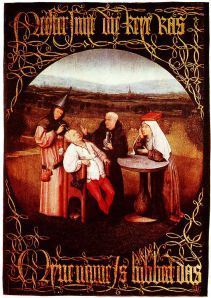

An illustration of a trepanation in progress, from Hieronymous Bosch (1450-1516)

One of the misconceptions that moderns have about this surgery is that the primary use was to “let out evil spirits,” that it was a misguided and dangerous act, likely perpetrated against persons with mental illness or migraine headaches. Here is another example of the failure to recognize the granularity of history. There are suggestions from ancient artworks that such a goal might have been behind some number of prehistoric trepanations. Interestingly, evidence from graveyards suggests that about 75% of persons who underwent the surgery in prehistoric Mesoamerica survived (the bone has had a chance to heal).

Statistics from 14th century cemeteries have similar results. But were they performing the surgery for the same reason? Both Mesoamerican combat, featuring cudgels, and medieval combat, featuring flails, hammers, axes and falls from horses, have a pretty high level of cranial injuries. The one area where modern practice for a long time encouraged trepanation (and depending on the injury still does) is that of compressed skull fracture, where the skull is pierced and instruments use to elevate the broken bone to relieve pressure on the brain. Ambriose Pare, in his Apologie and Treatise, describes just such a recovery when he treated a knight struck by cannon shot who lay for 14 days “without saying a word” after vomiting and convulsions, until the trepanation was performed. As to the frequency of the operation, Pare says that, after the assault of Rouen, 1562, he performed eight or nine to relieve those who had been struck by stones during the siege.

And in the earlier Chirurgia Magna, Guy de Chauliac presents several pages of descriptions of head injuries, with reference to similar lists by earlier surgeons, and discusses how to treat them, including admonitions against cutting if it’s not necessary, and reference to the caution required to interact with the dura mater protecting the brain. He does caution against performing the operation at the full moon, interestingly because “the brain is puffed up against the dura mater.” So he gives an astrological explanation to the underlying concern about swelling which requires this level of intervention to begin with.

Most of the historical medical texts I have here in my office cite trepanation only in regards to the treatment of head injuries. There are numerous references on-line to the idea that it was used to treat mental illness, but the citations for these lack documentary evidence and are based on theories applied when the skulls do not appear to have suffered trauma as from an injury. (here is one nice article describing the history of research on trepaned skulls from archaeological sites) So I’m starting to wonder about the persistence of the notion among laymen that the primary use of trepanation was for non-medical purposes. If you know of articles or evidence relating to such uses, please pass them along!

Certainly, there are people today who believe that trepanation could open new levels of consciousness, including those who go so far as to advocate or attempt self-trepanation. I will not give them the authority of linking to their material, but if you are curious, a simple google search will suffice.

As an aside, you will also see the term “trephination” used to describe this operation. The trephine was a specific tool for cranial surgery developed during the middle 1500′s to reduce the likelihood of accidental penetration of the brain by allowing a one-handed use, and by introducing a sort of truncated cone-shaped circular drill so that the opening in the bone widened outward.

November 14, 2013

Clarity of Writing, Thanks to Charlemagne

When I’m writing for the web, one of the things I keep in mind is to note the length of my paragraphs. Too long, and readers’ eyes will simply glaze over. We seem willing to focus a little longer on the printed page, but even then, if I see a paragraph that takes up most of a page or slops over to fill up the next one, I kind of assume that nothing is happening–action tends to occur in smaller bursts, dialog in a particular format, and both of those are more likely to advance the plot and develop the characters than a long passage of introspection, description or exposition. Certainly, a skilled author can make those long paragraphs just as compelling, but, visually speaking, they send up a warning. A warning for which, we may have the Emperor Charlemagne to thank.

In most cases, our eyes fall upon a block of text and automatically begin to read. For just a moment, though, I’d like to squint a little bit, and think not about what is being said, but about the visual aspect of the process that conveys information from the author to the reader, much of which began around the time of Charlemagne (c. 742- 814 CE), and possibly at the palace school and scriptorium he founded. Several of the vital elements of clear writing began at this time–exciting innovations like: space between words! initial capital letters! (and, the biggie) the paragraph!

yesitstruebeforethatmanydocumentswouldsimplyhavethewordsallcrammedtogetherwithlittledivisionbetweenonewordandthenextonesentenceandthenextonethoughtandthenextWiththeoccasionalCapitollettertoemphasizeanImportantword

Gah! I”m exhausted already–give that a try yourself (it’s okay, I’ll wait). It was almost impossible not to hit the space bar, wasn’t it? But during the early middle ages, niceties of punctuation, standardized spelling and spacing were rare. Fortunately for those scribes, literacy was rare as well, so most ordinary folks didn’t have to wade through texts like the one above. The writing of the time is also rife with idiosyncratic abbreviations to save time and ink, combined letters or letters left out (as in the habit, in Hebrew, of leaving out the vowels entirely, leading to much consternation as future scholars attempt to interpret what word is meant by a short string of consonants).

A discovery announced just in January of this year suggests that the script associated with Charlemagne, the Carolingian Miniscule, was already in development prior to the great king. There were attempts made in various times and places to clarify text visually, including the use of small symbols to designate paragraph breaks, including the Pilcrow (that little double-lined “P” symbol used in word processing programs for the same function) which may have developed from a Greek approach to paragraphing.

However, it’s under Charlemagne, with his school training students in a more uniform fashion, and his expanding administration, that the structure of writing begins to be codified. Nowadays, with the advent of texting, the habit of leaving out vowels, creating new abbreviations and using obscure symbols to convey a more complete message is returning. Still, as you write your next memo, email, or chapter, take a moment to squint at the text through the lens of history,and give thanks to Charlemagne and those who made our words–a thousand years later–so much more clear.

November 5, 2013

Henges and the Barber Surgeon

I recently had the opportunity to visit Stonehenge from the inside, on an English Heritage members’ tour that included a walk around a few of the many other sites in the area (Woodhenge, Durrington Walls, King’s Barrow and some Bronze-age round barrows as well). One of the reasons I love writing into British history is the sense of that layering of the past. Even here in New England where we had Native Americans moving through and some of the first settlers from Europe, there is little real depth to the history of human interaction with the landscape.

One of the outer ring at Stonehenge.

Nowadays, we view henges and other pre-historic sites with fascination, sometimes awe, curiosity at the very least. But, continuing in that vein of human interactions, this was not always the case. I give you the Barber Surgeon.

As you might imagine, my heart leapt at the name of the Barber Surgeon stone at Avebury, a stone circle not far from the iconic Stonehenge, and I only became more intrigued when I learned where the name came from. During the Victorian period and early twentieth century, much “archaeological” work was done (I use quotes because the early participants in this pursuit rarely attempted anything like academic or scientific rigor, resulting in many finds without provenance, certainly without detailed maps of the location of artifacts or any sense of their context—they had vastly different ends in mind, not always associated with the open-minded understanding of the cultures and histories they explore.) This enthusiasm included efforts to reconstruct some of the monuments brought low by time, including the Avebury stones, many of which had fallen.

However, when this particular stone was raised in the 1930′s, the re-constructors were startled to find a medieval body squashed underneath. You see, far from the reverence in which we now hold neolithic monuments, the folk of the Middle Ages had quite a different view. To them, these things were unholy evidence of a pagan past, possibly demonic in origin, certainly not a thing to appreciate or celebrate. Hence the hobby of coming out in groups to pull down the stones.

The fellow beneath the Barber Surgeon stone was, therefore, a victim of his own prejudice, apparently crushed in the act of tearing down a stone which had stood for thousands of years after its erection by those ancient peoples. The remains have been identified as a barber surgeon of the 14th century, based upon the belongings recovered with him: silver coins of Edward I or II, a pair of scissors, and a slender metal probe, likely of medical use.

His interaction with the landscape resulted in even greater evidence of human behavior, another intriguing mark upon the timeline of the place.

October 30, 2013

Pole Vaulting in the Middle Ages

While we associate Pole Vaulting today with the Olympic track and field competitions, the sport actually has an interesting history as a means of practical transportation. Practical? Transportation? Yep. I just learned about this myself, while I was listening to Hereward the Wake. Immediately, I wanted to know why I hadn’t hear of it before, though it did bring to mind one of my childhood favorites, The King’s Stilts, by Dr. Seuss.

the “lantern” of Ely Cathedral rising above the fens

Hereward’s region of north-central England is riddled with fens, swampy areas of deep water with occasional islands of ground solid enough to build bridges, houses, or Ely Cathedral. . . “Ely” actually takes its name from a contraction of “Eel Island,” ie, an island from which the eel fishery was especially strong, and the famous lantern (that octagonal cupola on top of the church) contained a light to help guide people across the dangerous fenland to the safety of solid ground. Fighting in this area gave William the Conqueror no end of grief, and some stories say that he drained the fens to make troop movement easier and give rebels like Hereward no place to hide.

In fact, the fens had been channeled, dammed and guided for centuries, for the ease of those already living there, who depended on small boats to get around, or on their trusty poles. A long, sturdy pole could aid the experience fenlander to leap these channels and pools on their way to check their fishtraps, bring in their eels, or perhaps attend service at the church. So the original pole vaulting competitions were not about height (which serves little use in progressing across the wetlands) but rather about distance–making sure you didn’t land with your feet in the muck.

There’s even a town in the area called “Hop Pole,” a name shared by a number of pubs, and attributed to the poles used to train hops plants for brewing. But if I get a chance to hoist a pint at the Hop Pole in Brighton during this week’s World Fantasy Convention, I’ll be thinking not of the brew, but of Hereward and his companions, vaulting the fens with easy, athletic grace while William and his French knights flounder in the mud.

October 23, 2013

Medieval Apps: There’s a Saint for That!

One of the aspects of the medieval Church which causes much consternation among theologians is the presence of and reliance on the various saints. Theoretically, the Catholic Church is monotheistic, that is, it worships only one god. First, they muddy the waters with the Holy Trinity–a feature that started a lot of arguments and some interesting heresies in period with the question of what the flesh vs. god ratio was for Jesus, and whether the Holy Spirit took precedence over both Father and Son. It can be pretty complicated for the modern researcher to follow some of those arguments–yikes!

Saints Cosmas and Damian, twin brothers and future martyrs, perform a leg transplant.

The saints seem a little more straightforward. Saints are, in essence, God’s posse, lead by Mary, providing intermediary services between sinners and the Big Guy. Generally person who showed signs of great religious devotion during life, or those who died as a result of their religious faith (martyrs), saints begin as ordinary people. This makes them seem accessible to the masses, especially when this new religion expands throughout the European continent and beyond in the early Middle Ages, when monotheism had a lot of competition from other religions which often featured an entire pantheon available for a variety of purposes.

So the idea of saints came quite naturally to the new believers, though the distinction between “worship,” which was reserved for God, and “veneration” which might be performed for a variety of holy figures was frequently lost. But, in reading some Church history, one gets the impression of bishops and other higher clergy running about trying to manage the increasingly unruly Cult of Saints. The process of attaining actual sainthood is complicated and lengthy–too long to satisfy local clergy confronted with miracle claims of their parishioners or with extremely devout behaviors on the part of some recently deceased person.

Saints, quite aside from their religious value, also meant profits–new chapels, expanded abbeys as people came to experience the sanctity of a local holy hero, giving gifts, needing services like meals and rooms, and perhaps dedicating children to service in the area.

The locals lobbied for their proclaimed saints to be granted official status, while the Church hierarchy struggled with the official process, managing investigations of alleged miracles and proliferation of local cults that often branched far from doctrine. Many of these local cults sprang up around the pagan centers of worship already in use, like sacred wells and trees, which might then be incorporated into a Catholic church–or might be roundly rejected by the more orthodox.

Some saints are associated with particular types of work very early on, while others are attributed to an area of patronage based on their own lives or martyrdom, including some who are co-opted for new purposes further down the road, like St. Roch, who is always depicted revealing a sore on his thigh, becoming the patron saint of plague victims after the advent of the Great Mortality (the Black Death, as we know it). Saints Cosmas and Damian, patrons of doctors, were famed for having transplanted a leg from one person to heal another–especially striking because the substitute limb is of a different skin tone.

Catholic online hosts a list of patron saints from Aloysius Gonzaga, patron of AIDS caregivers (and patients) to Francis of Assisi, appearing here as the patron saint of zoos. In between, you will find all manner of other saints, including two for marriage (one just for unhappy marriages!).

No matter your need, spiritual or secular, you’ll likely find there is a saint for that.

October 16, 2013

The World’s Second or Third Oldest Profession?: Storytelling

Last night, on the way to a book launch for an author friend (Justine Graykin’s release of Archimedes Nesselrode, which she describes as a “palate cleanser” for grittier works of fiction–so it’s a handy thing to read if Elisha Barber left you feeling a little unsettled), I had a nice chat with my carpool partner about storytelling. He advanced the claim that storytelling, so vital to the human psyche, was likely one of the oldest professions.

The list of early occupations, when people started to specialize, likely includes hunter, gatherer, shaman (in a dual role as both healer and priest). After this comes farmer, warrior (who might also be a hunter), administrative professional, potter, basket-maker, tanner. . .The question in my mind is, who, at the start, were the storytellers? Was it, in fact, a specialized occupation in the paleolithic, or rather, was it a facet of everyone’s life?

Before that question, though, I should note that there are numerous psychological studies about the utility of stories and how strongly we are drawn to them. I think this relates to the biological principle of the Theory of Mind. All animals develop some sense of the flow of their world–where and when they are likely in danger. Higher predators take this sense further, constructing an internal narrative predicting what other animals will do. Hence the cat who, seeing another cat heading for a door, sneaks around a piece of furniture to pounce on it, correctly predicting the cat’s arrival there. Storytelling is an especially elaborate Theory of Mind, one that has often become completely detached from its usefulness as an evolutionary mechanism (although there are also those who argue that hearing the right kinds of stories still prepares people for action).

We often envision an early man (yes, most likely a man, though it’s now believed that women also took part in group hunting activities), returning after a successful hunt and telling those who remained behind all about it. Gary Paulsen said in an interview, “When I write a story, the hair goes up on my neck. I taste blood. I put bloody skins on my back and dance around the fire and tell what the hunt was like.” In spite of that vivid description, then, the earliest stories might well have been the ancient equivalent of answering the question, “How was your day, dear?”

At some point, before or after this, comes the stage of explanation, of what has been handed down to us as myth. That same hunter, now unsuccessful for many days, comes to the shaman to ask what’s happened to the animals. And the shaman will tell him a story, probably involving Platonic models of the animals, who exist beyond this realm, or other beings inherent in the land and in the life they live, who must be approached in certain ways–worshiped, sacrificed to, honored in the hunt.

But neither of these tellers of tales is a professional, dedicated to that line above all others. The figure of a lore-keeper, a scroll-keeper, one who holds the memory of the clan, appears often in fiction–when might such a person have developed in the real world? It’s hard to say–but I suspect their prevalence in fiction has much more to do with authors than with anthropology: because we love what we do, we incorporate it into our work–less out of hubris than out of the belief (real or imagined) that it is just as exciting to others. Hence the large number of authors as protagonists for stories.

Another writer friend once imagined us back at that campfire by the cave, assuming that our drive to tell stories was so strong that we would have been tale-tellers even then. I remarked that, given the age and health of many members of the group, chances were that most of us would be dead. Yeah, I know, way to spoil a pretty vision, E. C., just had to bring the historical perspective into it.

I am delighted to live in an era where story-telling is so highly prized that people like me (as well as scriptwriters, game developers, playwrights, comic artists and other narrative professionals) can be paid for what we do. I am also amused to live in a time where our profession is, in some sense, returning to its roots–the idea that any member of the tribe has a forum in which to tell his or her tale. That forum, that world-wide campfire, is right here, on-line. And you don’t even have to don your bloody skins to participate!