E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 19

July 2, 2013

Elisha Barber Book Launch–today!

Today’s the day I’ve been waiting for for almost twelve years: Elisha Barber hits the bookshelves!

cover image for Elisha Barber, from DAW Books, cover by Cliff Nielsen

Thanks to all of you who have pre-ordered the book already, and to those who plan to pick it up today. If you’d like to help me spread the word, here’s a handy tweet you can use or convert for other networks:

@ECAmbrose launches novel #ElishaBarber fantasy, intrigue, medieval surgery! sample at: http://www.TheDarkApostle.com

I would also appreciate your reviews and ratings on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Goodreads, or anyplace you feel it’s appropriate to share.

I am grateful for all the support I have received from my friends and family, my commentators and followers here on the blog and on other sites.

I hope to see some of you in New York tonight at the New York Review of Science Fiction Reading series, featuring myself and Kate Elliott! Reading starts at 7 pm at the SoHo Gallery of Digital Art.

Looking for other readings and events? Consider becoming a Disciple of the Dark Apostle–you’ll get a free short story download, and an occasional newsletter with more information about appearances, freebies and fiction online and off.

June 26, 2013

To Know the Future

As you know, next week will see the launch of Elisha Barber, and with it, the culmination of a dream which will hopefully lead to many more. Will it be a success? The suspense is killing me! And it makes me wonder if this is one of those times that I already knew the ending.

In my article, “Spoiler Alert!” for Clarkesworld magazine, I used some recent research into how people enjoy stories, and some examples from Tolkien, to argue that readers often prefer to know the ending of a work–it’s been shown to enhance their enjoyment of reading. Prophecies, time machines, and prognosticators of various sorts are popular elements of speculative fiction. We want the stories to be twisty and unexpected, but we want the surprises to fall within a certain range or comfort. Would I rather know now if my book will hit one of the bestseller lists? What if it merely rests in the mid-list, or sinks to oblivion?

In some ways, it would be a comfort to know. Like the readers in those studies, it would take some of the pressure off, and, perhaps, allow me to enjoy the journey of arriving at that known end point. In fact, this desire to be certain of the end has been a driver of many aspects of human culture, perhaps from the start. (and you thought E. C. was giving up history in favor of blogging about writing–ha!)

Stonehenge at Dawn

Stonehenge is only one of many ritual centers constructed by early peoples around the world which contains built-in predictive inclinations based on the rising of certain stars at certain times of year. Imagine, if you will, the dark and worrisome days–and the great peace there must have been in knowing that the pattern of the stars themselves would return, that the sky, while it seemed to be changing, was, in fact, a constant. No wonder people began to name the patterns they saw and to shape stories for them, as if the stars (or, as in Peru, the dark spaces between them) were familiar creatures and old friends.

From there, it’s an easy step to imagine that these stars were placed by one or more great deities, for the deliberate use of his/her/its/their creation. We like to believe there is an order to the world around us, that, even if we don’t understand it all, there is structure and direction. Just as in my entry about finding the right ending, there is deep satisfaction in seeing the pattern we have begun fulfilled in a way that seems appropriate. It seems natural that we would postulate a writer–a creator–who has envisioned such a structure, and thus, such an end. In our holy books and stories, we imagine what the world after death is like, and are soothed by the vision, by knowing what will come.

Then we take a few steps closer, we make that ending personal. It’s no longer enough to gather at a ritual center to greet that returning star, we want to know how the star affects us, and we look for the pattern that will lead from the particular place we are, to the place we’d like–or fear–to go. Hence the medieval popes and monarchs who consulted astrologers, and the medieval physicians who explained the plague as caused by a conjunction of the planets which affected the air. Back around the turn of the first millennium CE, the Chinese created highly sophisticated astrological clocks, in large part to be able to write down the exact moment of the birth of an imperial heir, and use that information to predict his future. What would he be like? What sort of reign could he expect to face?

The desire to know the future has driven the creation of great works of architecture and engineering, the development of religions, the invention of new technologies. In fiction, it leads to the use of prophecy, the delivery of teaser readings or excerpts by the author, the creation of fan-fiction and whole websites devoted to speculating about what will come next in the series.

For millennia, humans have sought comfort in creating certainty about the future, whether it is for ourselves, our children, or our fiction. And yet, if we knew, truly knew, might we then stop searching the stars? If we knew how our dreams would end, might we not stop dreaming them?

#SFWApro

June 22, 2013

Guest Interview: Gail Z. Martin, author of Ice Forged

It’s been a while since I had a guest on the blog, so I’m excited to host Gail Z. Martin, author of Ice Forged, to tell us a bit more about her work. If you’re into action, character, and rich world-building, you’ll love Gail’s work. If you ever have the chance, go to one of Gail’s readings and let her bring her words to life. But I’ll let her tell you more. . .

Cover of Gail Z. Martin’s latest, Ice Forged

Q: Ice Forged is the first book in your new Ascendant Kingdoms’ Saga series. What comes next?

A: Ice Forged introduces readers to the kingdoms of Donderath and Meroven, and to the disastrous war that destroys both kingdoms and makes magic fail. Readers also meet Blaine McFadden, a disgraced lord, convict and exile who just might be the only one who can put things right.

The story will continue in early 2014 with Reign of Ash, and we’ll see more of Blaine and his convict friends as they deal with their post-apocalyptic world. The bad guys are back, too, with even bigger plans to use the chaos for their own ends, and there’s plenty of action, betrayal and surprises.

Q: Why a post-apocalyptic medieval setting?

A: Why not? After all, the real Middle Ages were no stranger to devastating natural disasters like famine, plague, and even volcanic eruptions and severe climate swings. For the people who lived through those hard times, I’m sure it felt like the end of the world. I’ve always been fascinated with those periods in history, so I decided to create my own!

Q: Why is the failure of magic so important?

A: In Blaine McFadden’s world, magic is the convenient short-cut. It’s like our power grid. Sure, you can wash clothes without electric appliances, but it takes more work and nowadays, does anyone remember how? It’s the same way in Blaine’s world. The old ways of doing things without magic have been forgotten, and people have come to rely on magic for as a quick fix. Imagine what a shoddy workman could do with a little bit of magic, things like propping up a poorly built wall or shoring up a sagging fence. When the magic fails, so do those fixes, and things literally begin to fall apart. Then there are the bigger magics, like keeping the sea from flooding the shoreline or using magic to heal. When magic doesn’t work anymore, how do you heal the sick or keep back the tide? Donderath has a really big problem on its hands.

Q: How did you decide to make your main character a convicted murderer?

A: Blaine’s not just a convicted murderer, he’s completely unrepentant about killing the man who molested his sister. He did what he felt he had to do, and was willing to accept the consequences, whether that meant death or exile. I wanted to create a situation which put Blaine into exile, but at the same time, I wanted readers to identify with him and think, “yeah, I would have done the same thing.” He’s not a squeaky-clean hero!

Q: Where can readers find your books?

A: My Chronicles of the Necromancer series, Fallen Kings Cycle books and Ascendant Kingdoms Saga books can be found in bookstores everywhere. I also write two series of short stories, the Jonmarc Vahanian Adventures and the Deadly Curiosities Adventures, which are available on Kindle, Kobo and Nook.

The Hawthorn Moon Sneak Peek Event includes book giveaways, free excerpts and readings, all-new guest blog posts and author Q&A on 21 awesome partner sites around the globe. For a full list of where to go to get the goodies, visit http://www.AscendantKingdoms.com.

@GailZMartin Book Giveaway on Twitter—Every day from June 21 – June 28 I’ll be choosing someone at random from my Twitter followers to win a free signed book. Invite your friends to follow me—for every new 200 followers I gain between 6/21 – 6/28, I’ll give away an additional book, up to 20 books!

Gail Z. Martin, author of Ice Forged

Gail Z. Martin is the author of Ice Forged in her new The Ascendant Kingdoms Saga (Orbit Books), plus The Chronicles of The Necromancer series (The Summoner, The Blood King, Dark Haven & Dark Lady’s Chosen ) and The Fallen Kings Cycle (The Sworn and The Dread). She is also the author of two series on ebook short stories: The Jonmarc Vahanian Adventures and the Deadly Curiosities Series. Find her online at http://www.AscendantKingdoms.com.

June 19, 2013

Sowing the Seeds of the Perfect End

I recently submitted a story to an online journal, and received some feedback from the editor, a couple of changes she wanted to see: first, the character’s motivation was unclear, second, the ending didn’t work. Well, motivation’s not too hard, a line here and a line there–but the ending? I wasn’t sure how to end the story any differently, without it suddenly becoming either a different story altogether, or simply much, much longer. The ending issue had me stumped.

So I worked on the motivation. I layered in some back story, changed the tone of a few lines of dialog, tweaked up a few images to draw out the symbolism and enhance the character’s concerns. Added maybe a hundred words overall as I worked through the piece from beginning to end. And you know what? By the time I got to the end, it was perfect. It didn’t need to be changed at all–because the newly sharpened motivation had made clear exactly why that was the right ending.

The seeds of a good ending are sown long before the ending arrives, and often before you even know what the ending will be. The ideal ending for a work is both surprising and inevitable. Surprising, in that you don’t guess chapters in advance what the end will be and how it will come about. Ever read a mystery where you know who the killer is the moment he walks on the page, then you read the whole book, hoping you’ll be wrong but you aren’t? Yeah. Chances are, you’re not reading that author again.

Inevitable, in that when you arrive at the ending, you smack your forehead and think, “Of course! It could have happened in no other way!” An ending that is inevitable, but not surprising, like the mystery where you already have the killer pegged, is boring. And one that is surprising, but not inevitable feels like a shock. It can provoke outrage and irritation–that’s not what was supposed to happen. It feels like the author simply tacked something on, or formed some pretentious notion that she would defy narrative convention with this abrupt change of direction.

Notice, I’m not saying what the ending should be. Happily ever after? Everybody’s dead? a great revelation, a return to balance, or a brave new world–the right ending depends entirely on the individual work to feel appropriate, and, to be exact, it depends on the beginning. That’s when you set the expectations for the range of endings the reader will feel are appropriate (potentially inevitable). The author defines the parameters of the world–dragons, space ships, interfering deities. Note that these things might be obvious or they might be subtle–a word, a reference that the reader will later recall with amazement when they see what a genius you’ve been. But if you produce a dragon at the end of a book that had no prior inference of the existence of dragons, readers will be angry rather than amazed.

Which brings me back to the ending of my story, and how it linked to the character’s motivation. The ending needs to not only cap off the action of the story in a plot-sense, it also needs to feel natural for that character. It should relate to the character’s needs, whether by fulfilling or thwarting them–hopefully in a way that is unexpected, yet consistent with the character you have established. My ending, as set up by the beginning, didn’t fit. Why was that the right ending for this character? I hadn’t shown the connection. By working harder to develop the character’s motivation, I revealed what kind of ending he needed, then delivered it.

Think about the last story you encountered or wrote with an unsatisfying ending. It’s entirely possible that it had the right ending. . . but the wrong beginning.

#SFWApro

June 13, 2013

Galen: the father of medieval medicine

I touched briefly on Galen in my article “Skinning your Own Apes,” because the title of that piece was inspired by an odd detail I noted in one of his works. But the man himself deserves greater length. The theories of medicine and anatomy he advanced influenced the foundations of medical practice for centuries.

Galen (129 CE- c. 216) was a Greek philosopher and physician who left a variety of treatises covering internal medicine, surgery and anatomy. Although it was Hippocrates who began the theory of the four humors that governed the moods of man and were related to four liquids in the human body, it was Galen who promoted controlling these imbalances as a pathway to health, and took up Hippocrates’ ideas about bloodletting to correct the humors, an idea that persisted for more than a thousand years.

In an era when human dissections were illegal, Galen’s use of animal dissections analogous to humans is worthy of praise. However, this did allow for certain misconceptions about things like, oh, say, the placement of the liver, and flaws in his anatomical charts for women which were based on pigs. Still, it made for a good base of knowledge for most purposes.

He also performed a variety of daring surgeries, including cataract surgery, and the use of ligature to control bleeding. While medieval physicians embraced most of Galen with perhaps too much enthusiasm, they did not subscribe to all of his techniques. Galen may have written as many as 600 treatises, of which only about three million words survive, thanks to their transmission and translation by Byzantine and Muslim scholars.

Galen was the acknowledged master by the university-educated physicians, so influential that any actual human whose anatomy defied Galen’s drawings was said to be the anomaly: it was Galen who was the authority, not the evidence plainly seen by the surgeon on the spot. Strange, to think that your own body would be taken for an aberration if found to be in opposition to the text.

During my period of study, the writing of medical texts always included a large number of shout-outs to those who went before, even if the author was planning to refute or ignore them. In the works of medieval medical authors like Guy de Chauliac, each description of a procedure begins with noting how the same procedure was handled by Avicenna and Galen (sometimes others as well), citing the work where the master had described his work, then elaborating, but rarely daring to defy his example.

Nowadays, especially in the medical realm, we prize the new. We assume that the latest science, the newest technique, the test or medicine just approved by the FDA is clearly the best. We seem to have swung to the opposite pole, always looking ahead for the answers, just as the doctors of the Middle Ages were always looking behind. Our technology and techniques affords a much more clear understanding of physiology, though in many areas of practice and daily medical care, it still requires courage to suggest the authority may be mistaken.

Flawed as he was, Galen stood as a medical pioneer, not only for his own era, but for centuries to come.

June 5, 2013

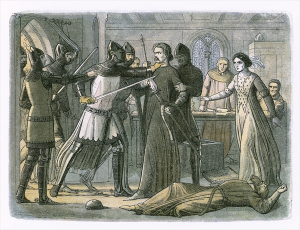

More on the Scandalous 14th Century

In our last entry, I was summarizing the fascinating story of King Edward II of England. We’d just reached the point where his estranged wife, Isabelle, returns from a visit home to France, in the company of exiled traitor Roger Mortimer–and a number of soldiers. Edward, seeing the small size of the invading force, assumed he could simply summon up his own army to defeat them, but he underestimated the extent to which he had antagonized his barons, and some simply refused their aid.

an illustration from an 1864 history of England showing Mortimer’s arrest by Edward III

After a brief campaign, King Edward II was imprisoned by his own wife, and his new favorite, Hugh deSpenser the Younger was castrated, hung, drawn and quartered. But the new regime was unstable, as you might imagine. What to do with a captive king? Unpopular as he was, Edward II was the anointed monarch of England, and many were reluctant to truly accept Isabella’s regency on behalf of their son, Edward III. What to do, what to do?

Here is where the chronicles differ. Most have Edward II mysteriously found dead in his cell at Berkeley Castle in 1327, presumably murdered by an agent of Isabella and Mortimer. Some even describe a particularly nasty method of execution involving a hot poker inserted in the king’s “nether region.” However, there are rumors of his escape–of a tall, handsome rider seen leaving the area, of an exiled king living in Italy, sending a letter via an Italian monk to his son. There is even a story about a tall, cloaked stranger coming to call upon the young King Edward III during a campaign in France–being allowed entrance to the king’s pavilion and staying for hours. Some intriguing possibilities.

After Edward’s presumed dispatch, the turmoil in the realm grows ever greater, with the barons expected to submit to a strong-willed queen, with her lover at her right hand. When Edward III came of age in 1330, he promptly had Mortimer arrested and executed on charges of treason, not least for regicide. Edward III tried to track down those responsible for killing his father to mete out justice, and even had his mother removed from public life, effectively under house arrest for the remainder of her days.

Edward III, much to the barons’ relief, proved to be a closer to his grandfather’s stock: a powerful warrior and savvy ruler who would lead them to some spectacular victories during the Hundred Years’ War. His own reign was blessedly much less scandal-prone.

May 29, 2013

Scandal, 14th Century Style

Scandals are all over the news these days, dominating the headlines and the op-ed pages, making some grumble that not enough is being done, others grumble that we’re getting distracted from more important issues. Let me tell you, as juicy or disturbing as you find the current scandals of the day, they can’t hold a candle to the scandals of the brief and turbulent reign of Edward II (b.1284 d. 1327).

Portrait of Edward II of England, from the Bodleian Library

I feel kinda bad for Edward, and in retrospect, a little sorry that my version allows him to be, ahem, displaced a little earlier than history, but I’m getting ahead of myself, and my hapless protagonist. Edward II came from great stock, the renowned warrior-king, Edward I, Hammer of the Scots. I don’t suppose they have such a great opinion of him in Scotland, but from the perspective of historians seeking examples of strong kings, he’s pretty impressive.

However, Edward II never got on well with his father. He’s notorious for having a variety of interests considered un-lord-like, and decidedly un-king-like: swimming, rowing, gardening. . . you can see how these interests, coupled with his extreme attachment to Piers Gaveston, a young man of his court, gave him a reputation, even in his own day, as a homosexual. Whatever the truth of their relationship, they were clearly devoted companions and rarely parted–except when Piers was repeatedly exiled by the king and forced away by angry barons who felt their own influence should be more than that of this Gascon transplant. Kings had favorites before, and after, and some may have been intimate–but Edward’s obsession with Gaveston went to extremes that could not be ignored by his nobles.

At Edward II’s coronation, Gaveston was crowned and feted almost as if he were the queen–much to the dismay of Edward’s wife, Isabella. Needless to say, Isabella and Edward had a troubled marriage almost from the start–including her near-abduction while supposedly being defended by his men after yet another failed battle in Scotland. Edward rightly feared for Gaveston’s safey, but was unable to prevent his capture and execution by a couple of the angry barons. He grieved deeply, but eventually replaced Gaveston with the powerful and unpopular Hugh Despenser the Younger, even illegally seizing lands from others to bestow upon the new favorite. I’m not even sure how many scandals that is so far: at least 8.

Naturally, as king of England, Edward II was already in trouble with France because he owed fealty for his lands there. He sent his (embittered) wife home to France to negotiate with her brother the king of France, taking their young son and presumptive heir with her. By the time she sent Edward’s men packing, she was already involved with the exiled Roger Mortimer, and the prince decided he’d rather stay there with Mom than go home to his father. By the time Mortimer and Isabella invaded, nobody was really surprised. . .

and that’s not even the end of the story! When people say that fantasy literature is byzantine, I point to this history. Truth stranger than fiction? I don’t know–but its definitely at least that scandalous!

May 22, 2013

Fantastic Beginnings: taking it slow, with Carol Berg

I have recently started reading Transformation, the first of the Book of Rai-kirah, by Carol Berg. I met the author on a panel about torturing your characters and recognized each other as kindred spirits. She’s actually the first person both my editor and I thought of to blurb Elisha Barber, but the bad and good news is that she’s been too busy with her own work. As a fan, I certainly don’t want to slow her down.

But it’s actually taking it slow that I wanted to talk about. From the first few pages of Transformation, I was already hooked, and now, as an author who’d like to learn from her, I’m trying to figure out what Carol has done to get me invested so quickly. As I’m considering her approach, I realized that one of the things she does is take it slow.

This seems counter-intuitive. The author wants to grab the reader as soon as possible, and it’s hard to even make it to the bookshelf through trad-publishing if you can’t excite the reader from page one. As a result, many authors bend over backwards to make something big, important and gripping happen in the opening line. This is one reason so many novels have prologues: you can use that big, impressive moment from the past or future, make it a vivid scene, then step back and introduce your world and protagonist at a slower pace. These prologues are often disguising flaws in the work. If the story you want to tell and the characters who will convey it are not interesting enough to be on page one, that might be a red flag.

So we find a way to start with action and conflict. There are other ways to hook. Some authors will go for a world-building hook, placing the coolness factor up front with a dragon, a beautiful landscape, a description of the cultivation of pipeweed. . . but still, one frets that it will be too slow for the modern reader.

Here, I’d like to digress for a moment to talk about rock climbing. As you may know, I also work as an adventure guide. When I’m working with new climbers, I often find them desperate to scrabble up the wall as fast as possible, flailing, hanging, missing better routes in the effort to get to the top. Sometimes, I quote them an old military mantra: Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast. Think about that. Absorb it. Because I’ve recently realized that the same can be true of writing.

The opening of Transformation is a first-person narrator being purchased at a slave market. We know almost nothing about this guy, except that he’s been a slave for 16 years, and was a warrior of a conquered people. That’s a nice set-up, sure, and the scene builds in some tension about the fact that the prince who buys him is capricious and without mercy, though the action here is pretty subtle and involves local politics and culture. What makes it work is that Berg is taking it slow, and making it smooth. It has a beautiful, organic movement. It builds the two protagonists and the world they occupy with deliberate care, like an expert climber on impossible rock, stringing together just the right moves for a thrilling ascent. Slow, smooth, and, in the speed with which she draws in the reader, startlingly fast as a result.

Rather than lunge quickly for a big, obvious hook, the reader is tantalized by this marvelous lure. Yes, I’m curious, show me more. As the chapters unfold, every tiny element of that careful first scene becomes freighted with meaning, and the apparently minor action of the opening leads to enormous consequences. Berg’s work is breathtaking.

Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast. I’m reading this book nice and slow, hoping to grasp even an ounce of what it can teach me.

May 16, 2013

Respecting Dan Brown

If you read Elisha Barber all the way to the end, you’ll find an Acknowledgements page. One of the first names on that page is Dan Brown. Yep, the same author everyone’s talking about this week, with the release of his latest title Inferno. Everyone’s talking, and many of the voices are loudly disparaging of Dan’s work.

I had the opportunity to meet Mr. Brown for the first time at the Seacoast Writers’ Conference in New Hampshire a few years ago. Right before The DaVinci Code came out. He taught a workshop on writing the series character, and I found him to be an excellent teacher whose workshop helped me to craft the character and concept that became The Dark Apostle. In fact, when Davinci Code broke not only big, but enormous, complete with death threats, one of my regrets was that Dan retreated from much of public life, including his teaching career. That was a loss for his potential students.

Some of you who have suffered my critiques or reviews have noted that I sometimes refer to an author as being a great writer “on a word and sentence level.” What I mean is that the prose is well-crafted, beautiful and smooth. The grammar is excellent, the style is strong without interfering with my enjoyment of the story it’s trying to tell. Not all writers are great on that level–and not all of those who excel at style and grammar can actually write a great book.

Dan Brown has written books devoured by millions of readers. Every time I see a critic jump on his stylistic quirks and flaws, I wonder if they realize they are not only trashing the author, but also proclaiming that yes, millions of readers *can* be wrong. I’ve found my own share of fault with some aspects of Dan’s work, but one of my touchstone sayings, from the lips of Tor editor and Making Light blogger Teresa Nielsen Hayden, is “What is important about a book is what happens in the mind of the reader.” Repeat that to yourself, authors (and critics). It’s important. Dan Brown makes extraordinary things happen in the mind of the reader. He takes them to distant, exciting places where they witness bizarre events, race to solve puzzles, and to stop crimes alongside a striking and unusual investigator. And 99% of his readers couldn’t care less about his style, as long as he delivers a ripping good yarn.

From the perspective of an author who aspires to the bestseller list (if not quite at the death threats and high fences level), rather than nit-pick the work of a popular author, I find it much more productive to ask what is he doing right? What does he create in these books, in this character, that makes readers return over and over? What elements are his readers thrilled by every time? In short, how can I once more be the student to this instructor?

If you want a start at discovering what Dan Brown, and many other big authors are achieving in their work, you might pick up a copy of Hit Lit” target=”_blank”>Hit Lit, by James W. Hall, a recent work analyzing a group of best-sellers.

In the meantime, Dan and I have clearly been reading some of the same books–he typically spends at least a year researching his work–and I, for one, am curious to see what he’s made of them.

May 8, 2013

Skinning your Own Apes: Researching from Primary Sources

An article in the Stanford magazine this month talks about a new method of teaching history to high schoolers using primary source material, having the teens read several documents about an incident and draw their own conclusions based on the information people had or understood at the time, and building critical thinking skills. Good stuff! This turns out to be a very effective way to get students involved in history–and also helps to bring the people of the past to life.

Many authors of historical fiction, or historically-based fantasy don’t do this. They read some basic history texts, secondary sources of the kind where a historian or general non-fiction author has assimilated and rearranged some information and presented it in a pleasing and intelligible form. Those sources can be a great place to start. They give you a solid grounding in the place or time you’re interested in, and can direct your interest to areas where you’d like to learn more.

But the real gold for understanding history is in the primary sources. One author suggested reading the books your characters would be familiar with, and that opens up some interesting avenues. For me, it meant rereading the Bible. Most of my characters wouldn’t have read it (they were illiterate, or were not allowed direct access) but the stories the Bible contains inform every level of Medieval life, including the art they would see in the churches they attended, not to mention the attitudes formed about everything they experienced. That’s an obvious example, but there are many more where this came from.

How about reading legal records? Laws and their consequences give us a good idea of the real priorities of the society. Nobody makes a law stating that you can’t hold a tournament inside a church unless someone’s been doing so–much less has to re-issue that law over a period of years. Repeated prosecutions of individuals for the same crime, say, homosexual prostitution, suggests that punishment was light, and social stigma did not deter the criminal: pointing out areas where the high-minded morality of the culture–the literature or sermons–might say one thing, but on the street, matters were much more open.

For my own work, I also examined medical texts. Guy de Chauliac, surgeon to Pope Clement VI, wrote a compendium of surgical techniques–how and why surgeons did what they did, the kind of things my protagonist, Elisha Barber, likely knew how to do. All the way back to the infamous Galen, the first century Greek physician responsible for all kinds of strange notions that persisted in medicine for centuries. Yes, these sources are crammed with useful information, but they can also provide the details that spark a scene or deepen the experience of a critical moment. Galen, for instance, highly recommends that students should skin their own apes rather than allow an assistant to do so. Why? Because, in getting that close to the subject, the student can examine and understand the connections between the surface and the substance of the matter.

Primary sources can be harder to use. They are sometimes abstruse, sometimes hard to find, sometimes written in a language you don’t read (I still lament and suffer for the fact that I don’t know Latin). They often strike the modern reader as boring. But they also represent the direct experience and understanding of people in times and places different from our own. They may serve to craft the fabric of that character’s society, like the Bible, or give you an idea of the actual labor and techniques he might employ, like Guy de Chauliac, but they provide layers of insight that a mere gloss of history cannot.

And so, my advice to you, if you would write fiction inspired by history: don’t just watch the History Channel, roll up your sleeves and skin your own apes!