E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 15

June 15, 2014

A Little Movie on the Virtues of Medieval Medicine (celebrating Elisha Barber in paperback, with a trailer!)

This week, Elisha Barber is available in paperback wherever books are sold–so if you’ve been waiting for the pocket-size version, now’s the time. It also includes a sample from the second book, Elisha Magus (you can read sample chapters from both on my website).

And to celebrate, I have created a little book trailer that I hope will amuse you–especially those of you with an interest in medieval medicine–in which I consider people’s concerns about Obamacare, also known as the Affordable Care Act, and give them something to take their minds off their health care woes–or at least,encourage them to be more grateful for what they have.

People who are enchanted with the pretty parts of the Middle Ages–chivalry, knights, princesses, tapestries of unicorns, flowing gowns and towering castles–often ask if I wouldn’t like to go back there. That, I can answer in one word: hygiene. Imagine a time in which many medical practitioners believed that water actually spread disease (which, to be fair, in some cases and places, it does) and thus that washing your hands, even, say, before or after surgery, was neither necessary, nor healthy. So if healthcare today worries you, click on the movie above, and think how different things could be. . .

June 4, 2014

The Uses of History: Inaccuracy and Injustice

One of my commenters on another post included the following: Kenneth Chase cites a book called “Teppo denrai” by Takehisa Udagawa who states: “If historical inaccuracy is ignored for the sake of the message then it is not clear what the message gains from being placed in an historical setting”

Which, as a historical fantasy author, has made me consider why I do what I do. I believe that my first duty is to the story–generally, the story of a character who faces great problems. History is an excellent resource for all kinds of problems. In the case of Elisha Barber, I wanted to examine a few problems–some on a personal level (what happens if your brother commits suicide, though his society believes he will go to Hell for it?), some on a more societal level (what happens when injustice is so endemic in a society that the lives of its lower-class soldiers don’t “count”?) How far is it right to go in service to a cause–would you die for it? kill for it? allow or encourage others to do so?

cover image for Elisha Barber, from DAW Books, cover by Cliff Nielsen

They cynics among us will have noted that these problems are still rampant today–especially those following the VA hospitals scandal and worried about how we are treating our soldiers right now. So why is the story set in a historical period?

First reason, history, like fantasy, is a sideways view of our own time. It’s been said that, no matter when and where a book is set, the author is always writing about his or her contemporary era. We can’t really help it–this time and place is, in spite of all research, what we know best. It is what has imprinted our psyche to form us as writers, and to suggest the things we are likely to be concerned about enough to write about them. So why not go into journalism to write about current events or ideas?

Here’s where the sideways comes in. People easily lose interest in the news. They feel a pang of righteous outrage when they hear or read about something bad happening to someone, somewhere–then it’s over and they click through on a link about easy weight loss. It is also easy to avoid difficult issues by simply avoiding following those news stories or reading the non-fiction produced about them (often while thinking, “well, that’s not *my* problem.”). A well-crafted novel, on the other hand, encourages sympathy with the protagonist(s) and draws the reader in through their adventure. The reader can feel close to the protagonist who is distant in time and place, without feeling pressured by what’s happening–after all, it’s only a novel.

Susan Sontag posited that the problem with over exposure to images of death, violence or degradation isn’t that people become insensitive to them, but rather that people become overwhelmed by helplessness about them. Why keep looking, why keep reading about a tragedy you can’t do anything about? In fiction, by way of that identification with the protagonist, you can. You can see that action can be taken, that it can be effective, at least in the world of the novel. If the world of the novel is Middle Earth, you might be inspired by the actions of the heroes, but not relate it to their own earth. A historical setting, on the other hand, still has real-world implications. It can be far enough from the reader’s experience to allow the reader to step away from today–but it is still connected, still suggestive of the substance of the world.

Phillip Zimbardo (creator of the Stanford Prison Experiment) and Zeno Franco wrote an article called “The Banality of Heroism,” in which they conclude that one good way to nurture the heroic imagination (leading individuals to think of themselves as potential heroes) is to encourage the reading and sharing of heroic narratives. Today is the 25th anniversary of the Tienanmen Square massacre, with its iconic image of that single, unknown person facing down a row of tanks. If a story can inspire people with that kind of strength and courage, I’m all for it.

But the commentor’s quotation begins with the idea of historical accuracy. Basically, it asks, if you’re not going to be accurate, why write into history? My question in reply is, where does accuracy begin and end? We don’t know as much about history as we think we do. A manuscript can turn up in an unexpected place that turns our understanding of a critical event or person on its proverbial ear. The archaeological record can be tricky to interpret, and the written documents (which don’t even exist for many times and places, and are incomplete at best) make little attempt at accuracy themselves–exaggerating the size of the enemy force, misrepresenting leadership as stronger or weaker, incorporating only a particular point of view. It’s only in recent years that we’ve tried to look for and include a variety of perspectives on history, and to make history not merely the records of the victor.

So even if the author wishes to be as accurate as possible given current information, he or she is already at a disadvantage. Next, there is the hurdle of audience investment. If the reader wants a history book, he’ll go get one. If the reader wants entertainment (and doesn’t mind some history) then he’ll come to historical fiction. The expectation of the genre is to present a solid impression of the historical time and place being represented–in the way that a stage set is a representation of a real house. You include the pieces most relevant to the story, display them in a way the reader can understand, and try to suggest the greater breadth and depth of possibilities outside the stage. Most authors of historical fiction attempt to be accurate in the items and aspects that are portrayed, but they also know they cannot portray them all. Something will be lost in the translation of the historical reality to the page of a book.

However, something is gained as well. A well-written historical novel invites the reader to explore another time and place, to learn more about that setting through the vehicle of a narrative experience. The fusion of a strong historical setting, with a story the reader can enjoy produces a work capable of revealing both the past and the present–and, perhaps, illuminating something about the reader that could be seen in no other way, through the sidelong glance of the historical mirror.

#sfwa

May 28, 2014

The “Bloody” Blog

There is an urban legend that the British slang term “bloody” is derived from the phrase “by our Lady” which is blasphemous and therefore ought not to be said, or perhaps the oath “‘s Blood,” as being short for “God’s Blood”. However, Steven Pinker, in his book The Stuff of Thought, and others have made the point that, while blasphemy is certainly one potent source of cuss words, the real goal of a good swear is to transgress the boundaries of taboo–and one of those boundaries is at the edge of our skin.

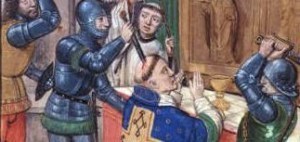

A medieval depiction of the martyrdom of St. Thomas a Becket in Canterbury–blood, and blasphemy.

“Bloody” is a strong word all by itself, referencing things that should go unseen, and the spilling of which suggest violence, danger, possibly disease. It holds the power to shock because it immediately heightens the tension about these possibilities–the piercing of the human body, the precious stuff within spilling, staining, and sickening those around. Other insults, such as Shakespeare’s “a plague on both your houses,” underscore a similar concern with that critical boundary of health, wholeness whose crossing may result in death.

However, the OED offers a different explanation for the word, and points to the transgression of a different boundary, in suggestion that the origin of its current use goes back to the 1750′s and the term “blood” as a short-hand for “blue-blood” meaning a member of the nobility. So, “bloody” would refer to doing something in the manner of an aristocrat–but its application as a derogatory word, as it is so clearly intended by those who employ it and treated by those who disdain it, represents the lower classes displaying a strong and negative opinion toward their theoretical betters.

The OED describes this word as “now constantly in the mouths of the lowest classes, but by respectable people considered ‘a horrid word’, on a par with obscene or profane language. . .” The entire purpose of words like this is to offend so-called “respectable people,” perhaps in this case, originally by claiming that the low-born had something in common with the high.

When I’m creating fantasy realms, the consideration of language, especially that employed by my characters, is significant. What words do they choose and why? Which characters would use a certain word or kind of word, and which would not? In a fantasy novel centered on medieval surgery, “bloody” as an adjective is highly functional. “Bloody” as a modifier suggesting the significance of the statement is handy as well, and “bloody” as a word that implicates the boundary between the healthy self and the chance of disease or injury, as well as one that points to class conflict between lowborn individuals like my protagonist, Elisha, and the nobles he finds himself confronting is excellent. To be able to suggest all of these meanings in a single adjective? Bloody astounding!

May 21, 2014

The Ancient Dead: A Brief History of Barrows in England

One of the things I love about Ordnance Survey Maps is all the little details of history that pop out when you examine them. England features a high concentration of man-made structures, spanning thousands of years, and Ordnance Survey strives to note them all (as part of their founding quest to seek out unexploded bombs after WWII). In particular, the land is riddled with barrows, mounds of land, generally over a stone core, commonly used as graves starting in the Neolithic period (3700-3500 BCE, in this case).

an exterior view of the chambered West Kennet Long Barrow

My recent visit to Stonehenge included a walkabout with two archaeologists specializing in this early history, and showed me all sorts of things about the landscape, some of which I noted in an earlier blog. Today, I’m focusing on the barrows. In America, I think most readers know about them mainly from Tolkien’s barrow wights, the ghosts inhabiting their tombs and enticing others to join them, notably, Frodo and his friends after they make it through the Old Forest in the Fellowship of the Ring. That barrow is clearly a long barrow, of a particular sort: not merely a pile of rocks over bones, it contains chambers, like the West Kennet Long Barrow pictured above.

Chambered barrows were more of a construction project than a landscaping one, because they feature linteled entrances and rooms inside for the placement of the dead over a period of time. The West Kennet Long Barrow was built around 3600 (400 years before Stonehenge) and used until 2500 BCE, during which time it remained open for the burial of about 46 people, and folks apparently went in and out, sometimes taking bones away for unknown purposes (have any of these bones been found elsewhere? I’m very curious).

The King Barrow near Stonehenge, by contrast, did not contain human remains at all, although secondary burials have been found in the upper layers–meaning that later peoples, seeing the site as spiritually significant, buried their own dead in the mound. Instead of human remains, this barrow contained cattle skulls. Apparently, such burials are common–often including hooves, and sometimes “head and hood burials” in which the cattle were skinned with their heads and hooves left intact, and these skins were they interred.

But getting back to those later peoples. . . the common round barrows, which often appear in groups or lines in the English countryside, date from the Bronze Age, around 2200 BCE. They are frequently placed in relationship to the existing long barrows from the earlier time, perhaps in the way that we think of the family plot or family graveyard. But then, how much did these later peoples know about the long barrows and their builders?

Whenever I read of assumptions about what early peoples were thinking, I remember an article about the excavation of a barrow in Northern England, which featured a variety of small animal skulls inserted among the stones. The researchers were fascinated as they came across and carefully documented them for later study. When were the bones left? Were they offerings? “Food” for the dead? Or sacrifices of some kind? Then, during a lunch break where they sat nearby eating and looking at the subject of their work, they saw a local cat trot up to the mound with a rabbit in its mouth, and stuff the rabbit in among the rocks for later eating.

Speculation is both fascinating, and dangerous. . .like Tolkien’s barrow downs, a constant draw for the curious and unwary.

May 14, 2014

Little House in the City–London, that is

One of the best parts of my job is claiming tax deductions on trips to England for research. The first time I went, I specifically needed to know what it felt like in a 14th century house. I wanted to have a strong impression of the sorts of buildings typical in Medieval London, in particular, in order to capture them in words for Elisha Barber.

This narrow Medieval street from a town in Dorset gives a sense for the architecture and feel of 14th century London.

There’s not many buildings of that era left in London itself, but there are lots of wonderful antique houses to see and visit around the countryside–several of which have names like “King John’s Hunting Lodge,” regardless of their location in the middle of a town far from any royal forest–and the fact that they all date from a couple centuries after the unloved King John himself.

Even visiting authentic dwellings furnished with original or reproduction items can be a bit misleading however, because I need to keep in mind two key things: these houses are now centuries old–and I need to picture them new or nearly so; and they were thoroughly occupied. The residents cooked over wood or coal fires, adding a particular atmosphere of light, scent and smoky air. They needed to store and prepare food, to wash and dry clothing, care for children, and, often, perform their occupations inside the house or in an attached building or yard.

My quest started, naturally enough, with books, including the Landmark Trust Handbook. I love these guys! They not only preserve old buildings and open them as holiday cottages, they publish this handbook with photos and floorplans of the houses themselves. I found my first copy, used, before I understood I could actually go and stay in the places it described. I’ve now stayed in several (including the standing Great Hall of a 15th century manor, and a thatched cottage in a seaside village) and I’m looking forward to staying in a castle when I go over for Worldcon. The chill of the thick stone walls, the lighting consoles high above, the narrow stairs tucked into odd corners all helped me create a clear vision of what medieval houses are like.

In order to envision them new, it helps to visit places like Dover Castle, which have been staged as if occupied, or some of the live medieval recreations–often feasts or special events. Fortunately, many of these events have been recorded and are also available online, including a Christmas celebration at the Tower of London. Filling in the smells based on reading period recipes–or better yet, eating them!–can help as well.

To transport these houses to London required the aid of archaeology, especially The Archaeology of Medieval London, and the Museum of the City of London, which has an excellent display of recreated homes from different periods. These resources provided a sense of the streets themselves, with their sewage ditches and twisting mews. All of which, I hope, have created an image in the reader’s mind such that, when Elisha goes home, his home feels as solid and believable as the home of a distant friend–a friend distant not in space, but in time.

May 9, 2014

Elisha Magus Cover Reveal!

Hey, Everyone!

This was meant to happen on Goodreads, which is not allowing me to change the cover image for the book today–not to worry, we’ll get it straightened out. In the meantime–Ta-da!

Cover of Elisha Magus, by amazing artist, Cliff Nielsen

In Elisha Magus, the barber-surgeon, feared and hunted for his spectacular regicide, finds himself under the protection of a duke, and offered the duke’s daughter, Rosalynn, in marriage. When Elisha escorts Rosalynn to a retreat in the New Forest, he hopes to recover the dread talisman stolen by his lover and teacher, Brigit, after the battle. Elisha learns more about the shadowy nature of witches and the truth of his own power: that he has become so close to Death that he is indivisible from it—a power that Brigit is desperate to learn. Does his knowledge make him a necromancer, feeding on the fear and pain of others?

When he befriends the discredited Prince Thomas, Elisha has the chance to forge a more just nation, but his enemies grow stronger and more vicious, wielding the power of death to craft a reign of horrors that will blacken the future of England—and maybe the world.

April 30, 2014

Of Popes and Saints

This week, in Catholic news, two former popes will be declared saints, after (mostly) passing through the canonization process. I say “mostly” because Pope John XXIII is being hustled through with only a single miracle to his name, when he should rightly have two certified miracles in order to pass muster. Saints are great publicity for the Church–they remind common folks of how to behave, and they frame the Church in terms of goodness (in order to be sainted, or even Venerable, the candidate must live an exemplary life.)

These fishermen are part of the elaborate wall paintings in Clement VI’s bedroom at the papal palace in Avignon.

There is not always a big overlap between Popes and Saints, and some Popes were notoriously more secular than holy, including Pope Clement VI, who presides over the Church during the 1340′s, the period of my Dark Apostle books. I’m sure I’ll have lots more to say about Clement later on in my series, but for now, let me just note that he was famed for the parties he threw at the papal palace, with its star-strewn ceilings, and hunt scenes on the walls.

The term “Princes of the Church” refers to the Cardinals, the highest order of clerics beneath the Pope himself, but it seems most appropriate for the cardinals of the medieval period, who maintained palaces near the Pope at Avignon, and also back at home, who dressed and ate lavishly, had many servants and retainers, and often carried on like the nobility of any secular country. There were notable exceptions, and every so often, the College of Cardinals, in a desire to refute charges of decadence, would elect a pope more given to prayer and contemplation. They would then often be infuriated by that individual’s desire for strict reforms, and for generally setting an example of piety that they might be expected to imitate.

Clement VI’s immediate predecessor, Pope Benedict XII, was one of these. John XXII before him had routed the Spiritual Franciscans, who notoriously lived in poverty and claimed that Christ and his disciples owned nothing at all–not the sort of lifestyle the Princes of the Church wished to be compared with. Benedict XII was a reformer who reconciled with the Spirituals, and tried to combat the growing excesses of monastic life (there’s an irony for you, the “excesses of monastic life”), but made little headway. The Cardinals likely elected the large-living Clement VI in great relief after Benedict XII’s passing in 1342.

Saints are meant to be examples for the ordinary believer, and intercessors with God, and the faithful are always excited to welcome new saints into the pantheon (er, if one can use that term :-) Will they have staying power and accrue devotees who seek their aid in need? Who knows. Interestingly, the retired pope Benedict XVI will also has been invited to attend the ceremony, for these two men-turned-saints whom he personally knew. I wonder if, under those circumstances, he will think of their saintly virtues, or remember their human moments–in recognition of the popes who were sometimes, all too human themselves.

April 27, 2014

Elisha Magus cover reveal will be on Goo

April 25, 2014

Take me to Your Readers

Tonight, I’ll attend my monthly session with my in-person writing group. This group has met for many years, with varying membership, and produced a number of novels and award-winning stories, and all of that good stuff. These are very smart, competent critiquers who often give me great ideas to use in revising my work. And yet, at the end of a meeting where we’ve been discussing my work, I often feel dissatisfied, and wonder if it is the right group for me. Should I have a group of more fantasy writers (this one is mostly SF)? I doubt I could find a more professional or committed group. . .

I love this book fountain in Budapest.

Then I had a chat with a writer-friend about the local, open-to-the-public writer’s group she’s been attending. I was a bit surprised by this. Didn’t she want a genre-specific group, rather than an ad hoc membership, mainly poets and memoirists, who happened to show up that night? Then she revealed her treasure. Instead of sending manuscripts around in advance for detailed reading and commenting, in this group, they simply show up and read a few pages aloud. And she can see in their faces if they’re enjoying the work. She gets the one thing from her group that I often feel is missing from mine: reader reaction.

You can’t beat a cold reading for testing the impact of a work. Do their eyes widen? Do they catch their breath? Are they glancing at watches or making little doodles on their own pages? I realized I’d actually done this with my Dark Crystal novel, The Darkseeing Stars (which you can download for free from my website). I brought it to a local group and read the first five pages out lout–and I could tell they were with me. They were excited by what they heard and they wanted more.

My writer’s group consists of these highly educated, widely published professional WRITERS. Sometimes, they have forgotten they are readers. They are the sort of people who will look up obscure points of Scottish history in order to comment on my work (if they don’t already know the history off the top of their heads, which they often do). They will take apart minute details of plot or character to show exactly why something is confusing or lacks tension. But what they rarely do is simply enjoy. They rarely sit back with the work and just *read* it, and tell me how it made them feel.

We are so well-trained as critiquers of each other’s manuscripts that it’s easy to fall into critical mode and start dissecting. We have, for years, been told we need to come up with evidence from the text, to be able to quote chapter and verse, as it were, to justify a response. So now, we’ve streamlined the process to simply eliminate the response altogether, and present the evidence.

You remember all those English classes where you weren’t allowed to state, “I liked it,” or “I hated it”? Certainly it’s useful to be able to state why, to find some reasons in the text to support the response–almost more helpful for the critic, because that’s how we train our own editorial eye to notice that stuff and do a better job in our own work. When I see or hear a long list of critical remarks about my work, I often am left feeling that it may not be worth revising because the critic didn’t actually like it, and that, really, is the bottom line with commercial fiction.

We need to keep in mind that the key is not to please English teachers with an essay about the themes in the work–the goal is to please a reader who will pick up the book and, if they hate it, put it back down and likely not pick up another one by that author. The people I want to please are not my professional writer-buddies, but my fans and readers. They want a well-written book, sure, but first, they want it exciting, active, engaging, they want a book they won’t want to put down.

Loved it? Hated it? let me know!

#SFWA

April 18, 2014

Consciousness, the Grail, and the Writing Process

On Monday evening, I had the chance to attend a presentation entitled “Grail Mania,” by Diana Durham, which included a scene from her play about Perceval’s meeting with the Fisher King and his vision of the grail. Maybe you’re a bit familiar with the tale from your own readings in Arthuriana, or from the film, “The Fisher King,” one of my favorites (which was, incidentally, brought to us by one of the Monty Python gang, well-known for their own interpretation of the Holy Grail.)

Glastonbury Tor, UK. The nearby Chalice Garden is one of the possible hiding places of the Holy Grail.

Durham’s presentation included her Jungian analysis of the palace of the Fisher King as an intersection between the outer world and the inner world of the authentic person, with Perseval (whose name may be interpreted as “pierce the veil”) serving as the link between the two. She spoke of the story in symbolic terms, attaching psychological significance to the various elements. There used to be a local conference, The Joseph Campbell Folk Festival, devoted to a similar thing: how do myths interact with our lives, how do they reveal personal meaning, why do they have so many things in common?

I don’t mean to sound cynical–far from it. It’s just that the researchers, and the audiences, often speak as if there is either some great spiritual significance or perhaps a deliberate act on the part of the story-maker to portray the human inner life through the tale. From the author’s perspective, the experience of story is rather different. I have often found this type of mythic resonance arising spontaneously within my work. It could be argued that, as an author, I’ve been exposed to more of this material, so I tend to mimic it. Or that, as a student of structure, I tend to adopt it, even subconsciously. Or perhaps that the reason I became a writer, is that I am already attuned to the deeper levels of the psyche.

I think the truth is both more, and less, than that. I tend to subscribe to recent thinking about the brain suggesting that humanity is wired for story. We are story-seeking, story-creating creatures because the ability to speculate and project what might happen was an adaptive skill for a naked ape in a dangerous world. We have now adapted this biological utility to serve the function of deliberate entertainment and teaching, often at the same time.

So when I write about a character who initially “refuses the call” as in Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, on one level, I’m just writing about a guy who, like any of us, is fearful about change in his environment. Like any of us, he resists it and has to be seduced into accepting in. If this guy has to take a journey through the darkness, maybe a cave, for example, I am playing upon our innate fear of the dark and the dangers it holds. I am tweaking my social-ape reader’s desire to be with others, not alone, to be safe. And when he emerges wiser and stronger, that’s because all of us want to believe that we will learn from our experiences, that we are capable of greatness, and that, if we achieved this new knowledge, we would share it with the world.

Piercing the veil? Why not? Who wouldn’t like to be the one who stands between, who discovers something amazing and is able to share that with the outside world? One of the reasons speculative fiction writers write this kind of material is to interact on the page with the notion of secret or forbidden knowledge, sudden insight, and leaps of faith or intuition. I don’t think most of the authors I know are thinking about the role of the sub-conscious in mediating between the outer world and the inner, authentic self, however.

And yet. . .all that I’ve said, and my experience with developing story, suggests that my subconscious is mediating something deeper. . . that, when I write, I am excited about the adventure, caught up in the character, hoping to pierce whatever veil lies between truth and fiction and show something more beyond it. And my subconscious is doing the work. It is providing me with plot turns, character traits and symbols that, when examined years later by myself or some inspired reader, will map beautifully onto exactly the kind of structure that Diana Durham spoke of.

Because, after all, while they pick up my book for the action and the character, it is that deeper layer that will keep readers returning to my work over and over again; startling resonance and a sense of discovery will encourage them to recommend the books, and to eagerly await the next one.. And that, to any writer, is indeed, the Holy Grail.

#SFWA