E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 16

April 9, 2014

Deleted Settings: The Traitors’ Gate

The Tower of London, built by William the Conqueror to dominate his new capital, has a long and fascinating history well worth reading up on. As I approached The Dark Apostle series, and especially the second book, Elisha Magus, it dominated my research for a time as well, but the scenes twist and turn, the plot grows and changes, and some of the scenes I envisioned for the book are no longer there, including one featuring the Traitors’ Gate.

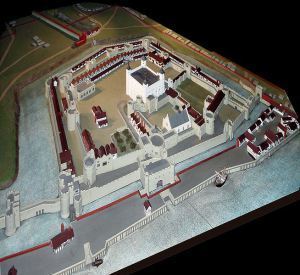

This model shows the Tower as it now stands, with the wharf extended down the river side, surrounding the rectangular St. Thomas’s Tower.

The Traitors’ Gate is a direct entrance from the river Thames into the the Tower grounds. This portcullis sits at the base of the large, rectangular St. Thomas’s Tower, and was built by Edward I in the 1290′s. St. Thomas’s Tower expanded the royal apartments, and provided a defensive bullwark at the riverside, as well as a protected basin for landing small boats on Tower business. Originally, St. Thomas’s Tower projected into the river, but by 1400, the Tower Wharf, which stuck out alongside the western end of the Tower by the city, had been extended the length of the river side to what is now Tower Bridge at the City Wall, thus completing the moat.

At some time, the water gate begins to be referred to as the Traitors’ Gate. I can date this usage to 1544, when the term appears on a panorama of London, drawn by Anthonis van den Wyngaerde (in the Sutherland Collection at the Ashmolean Library at Oxford). Likely, it was convenient to transport prisoners by barge along the river rather than bring them through the crowded city, especially for high-profile cases.

Perhaps, after the book is published, I can post my deleted scene(s) using the gate. Certainly, it’s murky and atmospheric enough to deserve notice, and the name alone inspires me.

April 3, 2014

A Brief History of “Romance”

I am putting the finishing touches on a novella set in the Dark Apostle world, around the time of the accession of King Hugh. I’m happy with the work, but also a little concerned that it might have too much romance. Definitely a lot of adventure, too, but are my fans okay with romance? Feel free to weigh in. . .

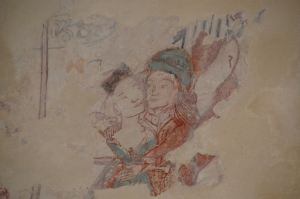

A medieval wall painting from St. Winifred’s Church, Branscombe, UK, depicting an embracing couple.

However, I should also note that this novella is based on some bits of Arthurian legend, and this lead me to remember the origins of “romance.” Nowadays, the word is so strongly associated with Harlequin novels and Valentine’s Day that we often assume there have always been hearts, flowers and scantily clad people involved. In fact, the origins of the term as applied to story are closer to the adventure side of narrative.

According to the OED:

“A tale in verse, embodying the adventures of some hero of chivalry, esp. of those great cycles of medieval legend, and belonging both in matter and form to the age of knighthood, also, in later use, a prose tale of similar character.”

The term is referenced here to the 14th century, and you’ll find works with titles like “The Romance of the Rose,” begun around 1230 BCE. These works are often compatible with the theme of Courtly Love, so prominent during the High Middle Ages. Some aspects of Courtly Love explored in the romances of the day include the idealized woman, the “lover” beneath her station, flowery declarations of love–and often tragedy. I used the word “lover” in quotes because, in modern parlance, it has the connotations of sexual love, but in the context of these works, it is more platonic. It likely includes lust, but that lust is rarely acted on. Indeed, the idea of distance from the beloved is another theme.

My novella is certainly all about chivalry and the idea of Courtly Love. It also agrees with the 16th century definition of “Romance” as a work remote in time or place from the present of the writer (though the OED says these works may include long digressions–I hope I manage to avoid those!).

It’s not until the 1830′s that the term “Romance” is applied specifically to “romantic tales.” We also use related terms like “Romanticize,” which relates to that 16th century literature remote in time and place–adding a dream-like quality to the work, or to the beloved, seen from such a distance.

I am certainly all in favor of history being messy, and of medieval fantasy in particular being more true to the reality of the Middle Ages. However, their reality of brutal warfare, loveless marriage and dangerous medicine also included this, well, romanticized overlay of chivalry: a Golden Age to look back to, when men like Arthur and Roland still walked, a noble ideal to live up to, a devotion to beauty and poetry which might have carried them through some very difficult times. And so, I must conclude that, even in my usually gritty and grim fantasy realm, there must be space for some old-fashioned “Romance.”

March 26, 2014

Longing for Spring: researching a historical garden

In just a few months, on July 1, Elisha Magus, book 2 in my Dark Apostle series, will hit the bookstores. Needless to say, I am thrilled. But when my window shows a snowy landscape, and my radio suggests that there is, in spite of having passed the official start date of spring, more snow in the air, thinking of summer seems a long way off.

And so, I am digging back into my research archives for a bit of research I did for Elisha Magus years ago, in the first draft. At the time, I was deep in the throes of Research Rapture, or how else would you explain a sudden obsession with English gardens? I was creating a little royal lodge in the New Forest, and I wanted to give it a more feminine touch to suggest the princesses who also visited there, so I had written in a flower garden, indulgent and frivolous.

A frosty rose in Cambridge, UK

But, being me, I couldn’t just throw in some descriptions of flowers and keep on writing. What would grow in the garden? What would be flowering at the time of the book? Internet, to the rescue! Thankfully, there are numerous specialists even more obsessive than I, like the good people at the Cowper and Newton Museum, who have graciously posted a list of all the flowers in their restored historical garden. This is a start, as they only use plants definitively known to have come to England prior to 1800, the time of William Cowper’s death. I, of course, am writing about 450 years prior to that. . .

So the list needs annotating. I have my version of the list in front of me, still residing in my research notebook. It took some doing to track down the flowers mentioned, to cross off those I couldn’t date to prior to 1350, and to make note of the appearance of the others. Some of these have medicinal uses (“Ox-eye Daisy, good for chest complaints”) or symbolic and ritual uses that sparked other ideas, like the fact that Periwinkle is said to be proof against witchcraft. A few flowers make specific appearances in the book as a result.

I also learned about the Devil’s Bit Scabious, a plant said to be so useful for so many cures, that the devil bit off its root in annoyance, leaving the plant to stay very short. Naturally, most of this is completely irrelevant, and the ultimate description of the garden remains brief and decorative, aside from mentions of a few plants Elisha can recognize–as it should be. But I enjoyed planting my little garden. Knowing just a bit more about Elisha’s world made it possible for me to visualize the scenes in that setting, the smells he would experience, the cetewall attracting butterflies, the foxgloves both useful and dangerous. Any detail that can bring me, and my reader, inside the story is a detail worth learning about.

March 13, 2014

Aliens Among Us

On my recent vacation, I had the opportunity to encounter some delightful earthbound aliens. We entered a long barn-like structure to view hundreds of plastic tubs in rows, full of water. The babies, so small and numerous, were simply called “fry,” like the young of any other aquatic species. I suppose you might call them cute–if you’re into tiny, wriggling worms.

In the “paternity suite” close by, we experienced their true nature. As we approached the tanks, they rose to the surface in small groups–six or eight occupy each tank, but they often travel in pairs. They’re monogamous, you see. At the surface of the water, they stared up with dark, shining eyes as if eager to see us, their mouths opening and closing in a silent song of welcome, their tiny head-mounted fins waving to keep them in place or move them about. Seahorses.

Hippocampus, or seahorse, photographed by Andrepiazza during a dive in East Timor (used under Creative Commons license via Wikimedia–thanks, Andrepiazza!).

These curious creatures of the sea are rarely seen in the wild, thanks to massive overfishing to supply household and commercial aquariums, and to use in traditional Chinese medicine (where, like so many other endangered species, they are said to be an aphrodisiac). The Ocean Rider Seahorse Farm is breeding domestic seahorses to try to fill the demands of the trade, and return many of them to their wilderness habitat. Yep, didn’t know anything about this until we visited their facility in Kona, Hawaii.

For some odd reason, my dad had a little collection of dried sea creatures that fascinated me as a child–among them a yellow box fish and a tiny seahorse. So the opportunity to see them up close made the rather expensive tour seem worth it. I did not know when I signed on that it would be one of the most moving alien encounters I would ever experience.

When an author is creating alien or fantasy creatures, there is a constant balancing act between making them engaging to the reader, and making them still feel alien. The seahorses manage this beautifully. With their bizarre appearance, prehensile tails, wavering head-fins and pouch-fitted fathers, they definitely look like creatures from the great beyond. They are predators (one of the things that makes them hard to keep in captivity) stalking the sea grass for tiny shrimp to devour. But they also pair-bond, and will pine away if separated from their mate.

As they bob about in their tanks, they often run into one another, sometimes by direction, sometimes apparently by accident, and seize each other with their curling tails. They then move together, inseparable, sometimes in clumps of a half-dozen at a time–an act hard not to take as affection, especially in light of their monogamous nature. When one of them decides it’s time to leave the party, he must struggle mightily to shake free of the others’ embrace.

If you experience any sort of sympathy with others, and are, like most people, the sort to project even onto the animal kingdom, it’s very hard not to read yourself into the lives of the seahorses, strange as they are. I think one of the reasons we keep pets is to have this kind of experience–the recognition of sentience–feeling–in a creature so clearly different from oneself. We enjoy learning to understand and communicate with these other species, and, once in a while, have that sudden warping of the mind in which we can envision what life is like for the other: how are we alike? how are we different? An experience that enriches both life, and fiction.

February 28, 2014

Bilbo Baggins’ Bathrobe, revisited, with special guest, Lisa Evans

Back at Arisia in January, I had the pleasure of sharing a panel on historical research with Lisa Evans. When I found out her specialty is European patchwork, I asked if she would write me a guest blog with her thoughts about my most controversial topic, Bilbo Baggins’ Bathrobe. I am delighted to present her findings below. I will add her bio and some comments at the bottom.

Film costumes are not like ordinary clothing, as fabric choice, cut, and color are crucial to creating the illusion of being in another time or place. This has largely been true of the costumes for Peter Jackson’s movies set in Middle-Earth, almost all of which are carefully designed to ensure that the characters wear clothing that looks right for their culture and social class.

The patchwork bathrobe worn by Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey is a notable exception. The problem isn’t so much with the robe itself; its rich colors, mix of printed and woven textiles, and velvet lining look wonderfully cozy and warm. The problem is that the bathrobe is about as close to what a gentlehobbit would have worn as a polyester disco suit.

Remember, the Shire is supposed to be a pre-industrial backwater with very little industry. Who brought such exotic textiles to Hobbiton? A wandering trader? Bilbo’s mother after a shopping trip to Bree? Where were they made, Minas Tirith? The Grey Havens? Harad? The other hobbits wear practical homemade wools and linens, so just where did Bilbo get his velvets and silks and damasks?

Equally problematic is how Bilbo could afford such fabrics. Even if they weren’t imported, brocades and silks are neither easy nor cheap to make, especially in a farming community. Bilbo may be well off compared to his neighbors, but a yard of silk velvet would be beyond the reach of almost anyone in the Shire. The only exceptions might be the heads of the powerful Took and Brandybuck families, not a bachelor from a respectable but not rich family.

Then there’s the patchwork itself. Patchwork today may be associated with thrifty housewives saving their scraps, but this became common only in the 18th century. Prior to that, the sole evidence that scraps were saved to create household items is a pillow made around 1450. Patchwork as we know it seems to have arisen around 1700, when fancy fabrics became cheap enough that a middle class woman could afford enough to piece a quilt top.

Worse, the actual fabrics used to construct Bilbo’s robe – brocades, velvets, silks – bear little resemblance to those used in early patchwork. These were usually light fabrics like dress silks, printed cottons, or imported calicoes that were basted over pieces of stiff paper, then whip stitched together in geometric patterns. Heavy cloth rarely appears in patchwork prior to the late 19th century.

This actually may be where the costume designers got the idea for Bilbo’s robe, which resembles Japanese yosegire patchwork. This style of piecing, which preserves small bits of fabric in accordance with Buddhist teachings against waste, inspired the crazy quilt fad after American needleworkers saw yosegire work at the Centennial Exposition in 1876. The results were striking and often beautiful, but they have no place in a rural, pre-industrial culture like the Shire.

Ironically, there is an existing patchwork bathrobe that would be perfect for Bilbo. This robe, pieced entirely of chintz diamonds, was made around 1820. Such a robe, known as a banyan, was a common at-home garment for middle and upper class men from the 17th through early 19th centuries. It’s a real shame the costumers didn’t give Bilbo such a robe, for he would have been not only cozy and comfortable, but appropriate to his time, place, and social class.

Lisa Evans is a textile researcher and historic reenactor based in western Massachusetts. She first became interested in quilt history in the early 1990′s, when she realized that there was almost nothing in print about medieval quilting and patchwork has devoted the last twenty years to researching, teaching, and writing about this fascinating subject. Her publications include a monograph on the wedding quilt of Catherine of Aragon and Henry VIII, an article on medieval European patchwork, and a paper on the relationship between historic reenactment and academic research.

I noted that Lisa’s research corrects my perception of the origins of patchwork as lower class. If, indeed, it began in the upper class, then perhaps, as one earlier commenter suggested, this robe is a mathom, a special gift passed down through the generations, possibly through the wealthy and adventurous Took line. (though I still question the types and varieties of fabrics it includes without the presence of a Middle Earth Silk Route).

I was struck by the image of the banyan robe–I recall seeing portraits of men wearing these, and I can readily imagine Bilbo settling back with his pipe in this style of robe. Thank you, Lisa!

February 20, 2014

The Seasons of War

As I set out from my home to do battle, once again, with the forces of Winter, I mused upon my recent reading, a historical novel, which, in part, depicted battles between Mongols and the knights of the European High Middle Ages, in the 1240′s.

There’s that bit in the Bible about a time to do this or that–and you can see it illustrated beautifully in various books of hours made for the nobility.

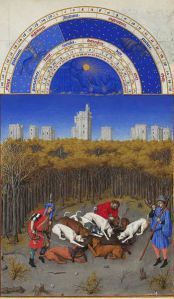

“December” from the Book of Hours of the Duke de Berry

Here is one example, a hunting scene representing December.Because only a fool would do out on military campaign during the winter. There is little fodder for men or horses, and one can run short of fuel for fires, not to mention becoming cold and uncomfortable. On top of that, there were no standing armies. Armies were made up of the men-at-arms and soldiers of each noble, summoned to fight in the cause of their higher lord, straight up to the king, and under obligation do do so for only a set period, to make sure that the men and their leaders could return home to tend their own lands and families.

And so, when we read accounts of medieval warfare, including the Hundred Years War between England and France, they are accounts that begin in the spring and wind up in the fall, either with the entire ad hoc army dispersing to their various homes, their time of service having ended, or with an army in a distant land considering where to camp or lodge for the winter, so they would be in a good position to start up again in the spring. A notably civilized way to organize the slaughter.

The Mongols were something else entirely, and their attitude about warfare is one large reason they were so successful, even against the famous Teutonic and Templar knights of this period. When the Great Khan set his tumons (groups of 10,000 soldiers) on a course of conquest, they just kept going. They scouted ahead for areas most suitable to feed men and horses, but they didn’t let little things like mountain ranges or bad weather get in their way, and they certainly didn’t turn back in winter. On the contrary, they turned winter to their advantage, once they realized that the Europeans expected the invasion to wait. The Mongols took advantage, not only of this expectation, but also of the frozen rivers that bordered and sometimes cut through the cities of Russia and Eastern Europe, riding their horses straight across, and right into the lightly defended riverbank opposite.

Now, as I lift and fling another shovelful of snow, I picture a rider emerging from the swirling flakes, his furred hat and his sturdy horse rimmed in white, his eyes gleaming and his bow at the ready. . .

February 12, 2014

Sad Tales of the Death of Kings: William II and the Rufus Stones

One of the curious features, to Americans, of the south coast of England is a area called “The New Forest,” which is, of course, many years older than most of the forests remaining to us in the states, and yet, has been carefully managed for a thousand years or so. It was founded, along with several other forests in England, by William the Conqueror as his private hunting grounds, where those without permission could be fined or mutilated for poaching the king’s deer.

Fallow Deer resting in the New Forest

Interestingly, legal records of the time suggest that, although harsh punishments such as the taking of an eye or even castration are on the books, fines were actually much more prevalent and the Conqueror and his heirs probably used such fines as an important source of revenue. Nevertheless, the founding of the Royal Forests was said to be cruel, casting out the villagers who once lived there and depended on the woods for their livelihood, and, perhaps, bringing down their curse upon the new king, who lost two sons in hunting “accidents.”

William Rufus, so-called because of his ruddy complexion, was the Conqueror’s eldest son, and became William II of England on the death of his father (1087). In August 1100 at the height of deer season, William Rufus rode out with a hunting party which divided so that some members served as beaters, sending game toward the archers. During this division, William Rufus was struck with an arrow through the lung. The nobles with him, perhaps justly fearing the consequences of the shot, fled and abandoned the body, which was subsequently found by a charcoal burner who loaded it in his cart to tend it.

The archer fled all the way to France, while Henry, the king’s brother and fellow huntsman that day, somewhat nonchalantly assumed the throne, leading many to speculate that the “accident” was, in fact, murder by collusion with the king’s younger brother. Hunting accidents were relatively common, but the hasty departure of the scene and the ignominy of the king’s retrieval suggest something else was going on.

Signage in the New Forest will direct the visitor toward the Rufus Stone, which allegedly marks the location of William II’s death. You can see it, and read more, at the New Forest National Park’s site. The entry on wikipedia is incomplete–it does not tell you there are, in fact, two Rufus Stones. One, as shown on both Wikipedia and the New Forest site, near Canterton, was erected in the 1750′s, and clad in iron in 1841 for greater durability.

The other is near the town of Beaulieu, home to the former abbey of the same name, and a good deal further south. Even the early chroniclers show some confusion about where, exactly, the king died, but recent study of the evidence available suggests the Beaulieu location is more likely. This stone is, well, a heap of stones, with a small, unassuming plaque about the king’s death.

The New Forest today still harbors several herds of deer–five varieties live there, including the lovely, spotted Fallow deer–though the wild boar also hunted there are gone. Herds of pigs and ponies graze among the widely-spaced trees, as they have done for centuries, limiting undergrowth in many areas. The copses, tracks, and tumuli remind us that this “New” forest, has been occupied and transformed by many generations of occupation, both before and after William the Conqueror claimed it for himself and for his ill-fated descendents.

February 9, 2014

The Lego Movie and World Building

I know, I know, I’ve promised to get back to historical blogging, and I promise I’ll blog later on this week about some nasty historical detail, really! So this will be a quick one.

Lego is about the most literal world building non-writers get to do on a regular basis. And if, like me, you have a hoard of these magic bricks, you know they have a universe of potential. So I was very pleased to see the Lego movie making use of so much of that potential. I applaud the film for surrendering to the Lego-ness of its medium. The laser shots were Legos. The steam from the steam engine–Legos! The water, the bubbles, the clouds of dust raised from the horses’ hooves–all Legos!

To those of you not indoctrinated into the realm of Lego, this probably sounds completely bizarre. But for me, as an obsessive world-builder, it’s perfect. I am so often frustrated when books or movies violate the culture and structure of the world they are trying to create and convince the viewer/reader is real. A recent example threw me out of a book set in Mongolia just after the death of Genghis Khan, featuring a teen on the steppes of the Mongolian plain comparing his view of the ger camp to seashells scattered on a shore. . .a thing he could not possibly have seen.

Mongolia then, as now, was landlocked, and this kid was, probably literally, a thousand miles from the ocean. Seashells in Mongolia were considered a striking and wonderful thing–and perhaps he might have seen one reverently kept by one of his elders who had traded for it along a line of strangers who may have been to the beach. He might have seen the image of one in Buddhist design. But a scattering of them? That would be a vision of remarkable treasures, not a glib comparison to the everyday sight of his home.

So to watch a film so true to its invented land was a pure delight. And the Lego movie was not afraid to be meta-fictional, calling on the tropes of the genre of Youtube Lego videos made by fans, using fishing line to make things fly and speaking in falsetto to voice characters who can’t bend in the usual ways of people. I don’t want to spoil it for those of you who have yet to go. Suffice it to say, this is a closely observed and remarkable work, one that manages to be both hilarious and moving. Bravo!

February 1, 2014

A Hobbit Fan’s Ire, More Fierce than Fire

Let me begin by saying that I think films and books are two quite different media, and they are good at different things, so it makes sense that a film of a book will be different from that book. I am also not a Tolkein purist. I really enjoyed “The Lord of the Rings” films, and I understood some of the changes that Peter Jackson made in order to make them more effective on film–like underscoring minor antagonists and enhancing smaller conflicts to carry on the tension when the major antagonist was mostly working at a great distance. He had a hard task in compressing three dense and detailed books into exciting action films, and some amount of elvish poetry and fun characters who did not advance the plot had to go.

So perhaps my fury with Jackson’s approach to The Hobbit is all the greater, because I formerly had great respect for his work. And now he’s gone and created the monstrosity that is “The Desolation of Smaug.” Those of you who have read my entry on Bilbo Baggins’ Bathrobe will know that I went into these films with some trepidation as the signs suggested his handling of the film would not be as deft and detail-oriented as it was with LOTR. When the rumor first surfaced that he would make 3 films, I thought the plan was to make two from The Hobbit, and another that bridged the gap. So the way the current film ends was, to say the least, a disappointment. But the ending was a blessed relief compared with what came before it.

Instead of a delightful journey through the countryside featuring dour dwarves and a plucky hobbit, we are given orcish raids and elves kicking butt. We are given ridiculous chase scenes and unbelievable dwarven mines. We are given romance, bird shit, and Gandalf behaving foolishly. We are given noble reasons to deflect the greed that underlies the story, and exposition from the mouth of Smaug himself. We are given an enormous amount of screen-time devoted to things far outside the sphere of the book. At least the alterations to LOTR mostly came from material already present. “Desolation” throws in so much crap that it starts to resemble Radagast’s hat. At one point during the dreadful inanity of the barrel-riding scene, the action so looked like a video game that I found myself thinking we’d unlocked another level–and should it be an ape throwing those barrels? Gaah!

But what makes me both furious and sad are all of the wonderful and thought-provoking things in Tolkein’s work that Jackson left behind. Gandalf’s faith in the dwarves and the hobbit. Instead of wishing them well at the edge of Mirkwood, he is called away on an urgent mission. Bilbo’s clever use of taunting and the ring to get his chance to free the dwarves, not to mention his leadership while they are still woozy–and the fact that they knowingly sought the elf fires, sending themselves into danger to escape the danger they were already in. His lonely search in the Elf-king’s halls to find a way to free his friends. The fact that he chooses the Arkenstone, knowing that it’s not something Thorin would give up, and ruining their friendship at the cost of greed, despite the fact that he later uses it to the noble end of bringing some of the combatants together. The Hobbit is a work rife with interpersonal, and inner conflicts, with moral choices and vast consequences.

And this is really the trouble. So many of the changes undercut the reasons we care about the characters. They undercut the themes that Tolkein worked with. They turn the dwarves into buffoons who must be rescued by the elves over and over again, stealing the silver tongue of Thorin and the quick wit of Bilbo. They give us less reason to root for these people, to worry for them, to feel proud for them as they struggle and grow. Not only did Jackson give this work an identity crisis by fusing it together with disproportionate heaps of absurdity and darkness, he gutted what it had been before.

I, for one, will not pay to watch the third film in this sequence. I am sorry I gave my time and money to see this one. If I had read this version as a manuscript to critique, I would ask the scribe what was the heart of the work–for it seems, sadly, to have none.

January 22, 2014

“Shaolin,” an Interesting Approach to Violence

As you may know, I’m currently researching Chinese history for a new project (don’t worry–there’s plenty more Dark Apostle to come as well!). I made a list of topics to research and one of them was the Shaolin Monastery school of martial arts, leading to the book American Shaolin, which was a fun read, and now to a Hong Kong martial arts film, “Shaolin” or “The New Shaolin Temple.“

Definitely, I love me some action films, and this one delivers exciting chase scenes, extraordinary fights and tense emotional moments. It was very enjoyable. I had been lead to expect something very violent, however, and was initially surprised by the grim, but rather distant opening. The film starts with the aftermath of a battle, horsemen riding down the survivors, and the shooting of a wounded enemy who seeks sanctuary with the monks of the eponymous temple. Yes, okay, it sounds violent, but it was also nearly bloodless. The violence wasn’t visceral, failed to startle much less to dismay. So I’m thinking the violence of the movie had been overstated, and that the “R” rating might even be exaggerated as I haven’t seen anything that wouldn’t fly on prime-time TV.

But the story of the movie is about Hou Jie, the shooter of that wounded enemy, who is later forced to seek refuge with the same monks. He’s a man of violence, through and through. His daughter even draws him looking angry with words saying that he likes shooting people. Over the course of the movie, as Hou Jie learns about compassion from the monks, the presentation of violence changes, and by the end, the blood flows, the blows have impact, the shots bring fear: the violence held at a distance in the beginning is now up close, personal–because our protagonist has come to a new understanding of violence, what it means to those it affects, how its ripples spread throughout a family or a culture.

I was reminded of a paper I heard at Kalamazoo a few years ago about the use of blood in the Mort’d'Artur. The author of the paper had found that the level of blood described in the text increased dramatically when the combatants were brother knights, when the conflict was personal and abhorrent to the laws of chivalry. It struck me that director Benny Chan was doing something similar on screen, using the language of cinema to suggest the change in his character, and, perhaps, to send a message to his viewers. Action films are fun. Martial arts is exciting to watch, challenging to learn. But violence is real. It has an impact on those who suffer it, and those who inflict it–and needs to encourage deeper thought in those who watch it happen, even at the distance of a screen.