E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 20

May 1, 2013

Handgun Control in Medieval Japan

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit a nice exhibit of Japanese arms and armor. Toward the end of the exhibit hung two very elegant matchlock guns dating to the Edo period (the 17th century). A small accompanying sign stated that firearms had been introduced into Japan in 1593 when a Portuguese vessel wrecked during a storm. This detail came from the Teppo ki, or Firearms Record of 1606.

Decoration on the stock of a Teppo, Japanese matchlock gun at the Higgins Armory.

As a researcher into the early history of firearms, I was startled. If firearms developed, along with gunpowder, in China early enough to migrate to England by the 14th century, how could they not have reached Japan before the 1593? The answer is, naturally, more complicated than that.

The entire Wikipedia section on this period in Japanese firearms is:

“Due to its proximity with China, Japan had long been familiar with gunpowder. Firearms seem to have first appeared in Japan around 1270, as primitive metal tubes invented in China and called teppō (鉄砲 lit. “iron cannon”) seem to have been introduced in Japan as well.[1]

These weapons were very basic, as they had no trigger or sights, and could not bear comparison with the more advanced European weapons which were introduced in Japan more than 250 years later.[1]“

footnote 1 refers to the text: Perrin, Noel (1979). Giving up the Gun, Japan’s reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 0-87923-773-2

Implying that the guns were simply not good enough to bother with. Given that the Japanese were also known for archery, it’s probably true that these early guns couldn’t compete with a competent archer. However, that was true in Europe as well, and especially in England, home of the longbow. It would be centuries before guns became accurate enough to rival the bow and arrow as a killing device. However, those early guns had other uses. Their explosive power and potential often frightened the knights and foot soldiers who first encountered them, and there are medieval stories of troops who left the field when the guns were fired, not because they were hurt, but because of the “shock and awe” effect of the noise, smoke and flash, which were often compared with the presence of Hell.

For a consideration of the period after the Portuguese introduction of firearms (dated to 1543, according to most sources) check out this blog about Guns in Medieval Japan. (despite the title of this entry, he’s talking about the 16th century onward, what historians generally term the Early Modern period) This blogger makes some of the same observations I might, referring to my own period, including the fact that guns, like bows, were a weapon that could be used effectively by a peasant. And, in particular, that they could be used by that peasant to take down a knight–a Samurai, in the Japanese context.

Distance weapons like this constituted a threat to the landed gentry, not merely to their person (they are a threat to everyone in that regard) but rather to their status. The feudal system relied upon certain tenets, one of which is that an armed elite in power over others was a necessity. These people controlled the land, and absorbed much of the income from that land, theoretically in exchange for the protection they offered. So the warrior class became a hierarchy of wealth and status, codifying their prestige into laws and attitudes designed to defend it, with distance weapons being regarded as low-status, cowardly devices that removed the honor from combat.

Does this have implications for the present day, with our shared concerns over personal safety leading to conflicting agendas? The blogger above, Ryo Chijiwa, along with the author of the book cited on Wikipedia both point out that the strict gun control exercised by the Tokugawa Shogunate (which began in the 17th century) coincided with 250 years of peace. It’s hard to say which came first: did the lack of guns result in a peaceful society, or did the peaceful society reject guns because they were deemed unnecessary except in time of war?

It’s interesting to consider what the historical perspective can show us about our contemporary woes. What are your thoughts?

April 24, 2013

Review: Songs for a Machine Age

Songs for a Machine Age by Heather McDougal

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This book is a delightful journey through an unusual fantasy world where machines and magic co-exist. While I didn’t find the heroine initially engaging, her talent for spotting the flaws in structures and the phrase “clown engines” intrigued me enough to keep me reading–and it was fascinating to see how the author used both of those elements to her advantage.

Elena is on the run from the baron who founded a movement against the Gear Tourniers: skilled makers of marvelous and elegant devices. The baron claims to act on behalf of common people, to give them the chance to participate in the creation of the things they need by working in factories after overturning the domination of the Gear Tourniers, and the Curator who stands above them all.

Along the way, Elena meets a variety of interesting characters–a scarred maker, an actor, a silver stag, a woman with amazing control over her body language. The complex relationships among these people add layers of tension and build the reader’s engagement with the book as you wonder how they will achieve their objectives. With this three-dimensional and striking cast of characters, McDougal delivers a rooting interest for just about anyone.

So, the flaws. As I said, it took me a while to warm to the protagonist–that’s one reason it took me so long to finish. As the work progressed, she rarely seemed to be the driving engine of the plot, it was often the others in her group who were making the important choices and taking necessary action, so the effect is more of an ensemble. In the last third of the book, when the characters split up to undertake various missions, the timelines don’t match up in a way that was confusing to follow, and made me think that, if it had been worked out more carefully, some of the plot elements simply wouldn’t work. One group of characters had a more-or-less continuous scene (in terms of the time they spent) but it was intercut with the actions of another group of characters which appear to take place over a period of days. Also, there are occasional intrusions of modern words or phrasings which stuck out in this otherwise distinctive world, and I’m not convinced that her use of technology is consistent with the time period emulated.

But if you like automata and antique machinery, this book will inspire your sense of wonder, pretty much from beginning to end. McDougal constantly reveals new marvels of gear and steam. The true Steampunk fan might be put off by the inclusion of talents of magical origin, but the author describes this as a “Maker” book–and, as a celebration of marvelous creation, it is spot-on.

April 17, 2013

What’s in a Name? The Naming of Elisha

It has come to my attention from two different and equally interesting directions that some people are wondering about the name of my protagonist, Elisha Barber, specifically, his first name. Some folks have even wondered if it’s my name (it’s not). The first to ask about his name is a very scholarly history buff follower of this blog who wondered how a peasant in 14th century England came to have this name, the second is the author of my first Goodreads review (four stars–thanks, Krystal!)

cover image for Elisha Barber, from DAW Books, cover by Cliff Nielsen

“Elisha” is a prophet from the old Testament, the originator of some interesting miracles and wonders which add some resonance to my book. It’s pronounced with a long “i” in the middle, not too different from “Elijah,” another Biblical prophet, and Elisha’s master. Are you confused yet? Thanks to Elijah Wood, the actor, most folks know how to pronounce that one.

A fun source for disambiguation (to borrow a term from Wikipedia) of the Elijah/Elisha confusion, if you ever have the chance, is the Reduced Shakespeare Company’s production of “The Bible: the Complete Word of God (abridged)” you can hear the song on their album of the show, but you won’t get to see the flashcards.

Of course, you can always check out Wikipedia for either of these guys: Elisha, or Elijah. (I am vastly amused that the Elisha entry is flagged for relying on a religious work without examining the commentaries, BTW.) I’d like to point out that my character, Elisha, is not a prophet, though he has certain unusual. . . talents. . .you will learn about in the book.

How did I choose his name? Biblical names have been popular in Europe for centuries, especially for boys, with a few always at the top of those annual Baby Name lists they come up with. The names trade places up there over the decades, but a name from the Bible is a pretty safe choice for a Christian of European descent. They are mostly New Testament figures (apostles are always popular) or big name kings from the Old Testament. If you check out , there, too, you’ll find the same names repeated over and over: John, William, Robert, Thomas, Richard, Hugh, Edward. And it’s here that the trouble starts. . .

I’m writing into history, relying on the milieu of the time, and sometimes on the people. And a very large number of those people are named William, Robert, Richard, Edward. . .so if I want to make the character my own, I need to choose something different, something unlikely, even, but believable. Looking down the rest of that list, I see a number of interesting names (Osbert, Wolfstan) but nothing that speaks to me about the nature of this character. It was to my own history I turned.

My father is a genealogy nut. He’s traced us back about as far as possible–yes, I’m related to Charlemagne (like a few million other people) and have a miniscule amount of African blood, thanks to a Roman consul who lived there. One of the families that fascinated me as a child hearing him speak about our history, were the Gores who came to America early on, and whose various children appear in battles here and there. What child of a certain bent could resist a name like “Gore”? And yes, one of those fascinating Gores was named “Elisha.” The name and surname, in my imagination at least, were tightly linked. What better name for a battlefield surgeon? From the moment I met Elisha, I knew his name.

While we’ve discussed and renamed some other key figures in the books, I am grateful, in spite of the potential confusion, that nobody ever suggested renaming Elisha. It was the name he was born with, from the fertile mind of that impressionable youth, when sowed with history, and sparked to write.

April 10, 2013

Focus Groups Taking over the World!

This morning’s Wall Street Journal features an article entitled “Test-marketing a Modern Princess,” about how Disney Junior is developing their new Sofia the First television series. Yes, folks, these executives are sitting down with pre-schoolers, reading them storylines and filming their reactions for later study. Given the ratings quoted in the article, it seems to be working. Should authors be taking a cue from some of these big guys and their market strategies? Some–whether they mean to or not–already are.

With the advent of social media, tribes of enthusiasts can gather as never before. Where an old-school Trekkie might have had to wait months for a con at which he could share his excitement about a new series, or perhaps set up a local fan group to meet on a more regular basis, the new fan merely has to open a browser and search for like spirits online. This offers both advantages and dangers for the author. For one thing, you can now eavesdrop on the conversations of fans the world over. If you’re deciding among projects to pursue, you can get an idea of what excites the kinds of readers you’d like to attract and see if one of your ideas will meet their needs.

Many in the trad publishing world decry the entire concept of “writing to market”, then, if you actually try to sell them a book, they will immediately turn around and ask you to define the market–what authors is your book like? what readers do you think will love this? And that’s all I’m really talking about so far. I’m a commercial author–I want to write books that will sell to a wide market, and it behooves me to have some sense of what that market is. It doesn’t mean I’m jumping on a bandwagon of urban fantasy about mermaids who live in the sewers of Denver, simply because some reader thinks they’d like to read that book. (would you? I’m thinking *not*) It does mean that I have enough ideas that I can cherrypick what I want to write based on what I think readers will be most excited to read. In that sense, the online focus group potential is a good thing.

It turns dangerous when it gets more personal. Because, of course, you can also learn what your own fans are saying. Whether you mean to or not, the author who works in series–unless all the volumes are out at once–is doing something similar to those Disney execs: showing a story-in–progress to an interested readership and receiving their reactions. What if they don’t like the direction it’s taking? What if they love a character you plan to kill off in the next book? Do you go all GRRM and kill him anyway? And will that make them more loyal because it raises the tension, or will it drive them away?

I know many authors who try to avoid the inadvertent focus group as much as possible. They don’t read reviews, participate in reader forums, or interact with fans who have ideas about the direction things might go. This was certainly a consideration for J. K. Rowling as the tension mounted toward the end of the Harry Potter series. I’m not aware of publishers being influenced by this sort of thing–they tend to adhere to the idea of the author as an individual creator, striving for a vision of the work which complies with internal rather than external ideals.

But there are also some interesting new authorial models online, things like fan-fic, in which fans literally write the plots they’d like to see for their favorite stories or even commercial ventures such as first chapters written by a pro author for books which will be finished by others. While an author might view the online commentators as a focus group on fiction, in this new world of empowered consumers, the focus group is no longer at the mercy of the author to provide its entertainment–if they get excited about an idea, they might just run with it, and wind up running the world.

April 3, 2013

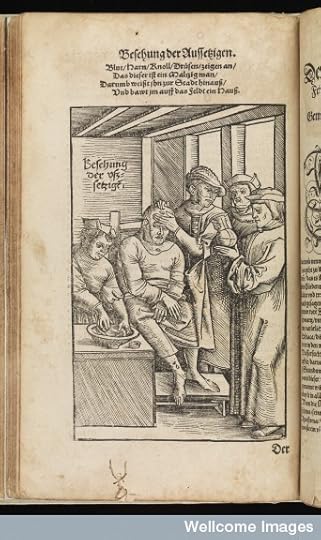

The Hierarchy of Medieval Medical Practitioners

Elisha Barber, the first book in my Dark Apostle series, features a barber-surgeon protagonist. During the Late Middle Ages (about 1300 to 1450, depending on whom you ask) the barber occupied one of the lowest steps in the hierarchy of medical practitioners.

A Physician examines a patient while a barber prepares for blood-letting.

Even below him, though often lumped together with him when disparaging remarks are made by their so-called betters, is the village wise-woman, who served a local, rural population as pharmacist, midwife and general practitioner. Her knowledge of herbs and traditional techniques, as well as her reliance on superstitious methods of healing, later made her a target of witchcraft accusations–but that’s another blog for another time. Mid-wives continue as a separate category of specialist even in cities throughout the period.

Working primarily in larger towns and urban areas, the barber not only cut hair and shaved beards, but also, by virtue of his ready razor, performed bloodletting at the order of a physician, or as a routine practice for clients who understood their humors to be out of balance. He served as a first aid technician, patching up wounds and extracting bad teeth, as well as performing common minor surgeries like lancing of boils and removing gall or kidney stones. Barbers learned their trade through apprenticeship and practice, and were expected to join the guild that regulated their role. A barber’s guild in London existed prior to 1308 at least.

Above the barbers, one finds the surgeons. Nowadays, if you ask a hospital nurse, you’ll likely find that specialist surgeons have an unparallelled reputation for arrogance. During the Middle Ages, however, surgeons were considered to be craftsmen, skilled with tools and capable of carrying out a wide variety of tasks. Most surgeons at the start of this period also trained by apprenticeship, but some of the universities had introduced surgery as a discipline, much to the annoyance of the Physicians, who sat at the top. Surgeons like Guy De Chauliac (surgeon to Pope Clement VI) and the later Ambroise Pare compiled texts to educate others and clearly had the respect of their contemporaries, as their high-status patrons can attest. The surgeons of London did not have their own organization until 1368, and in 1540, the Barbers and Surgeons merged into a single guild.

Perhaps this dichotomy–the high position of many surgeons versus their theoretically low status–can be explained by the increasingly divergent course of learned medicine represented by the Physicians. Physicians attended prestigious universities like Paris, Bologna, and later Oxford, where they studied the classic texts of medical knowledge handed down by the Greeks. They genuflected at the altar of Galen, who lived in the first century AD and acquired much of his anatomical knowledge from the dissection of animals rather than humans. They ascribed to the theory of humors: the four substances in the body (blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm) that supposedly caused illness in both mind and body. Their prescriptions might take into account not only the comparison of urine samples to charts, but also the season of the year and the patient’s astrological sign which were considered to affect the balance of humors.

While the physicians commanded the highest prices and the esteem of their wealthy patients, they often relied on surgeons and barbers, along with apothecaries to provide and compound medications, to actually perform any recommended interventions. “Drain two pints of blood and call me in the morning!”

March 27, 2013

Kelpie, by T. J. Wooldridge–cover reveal and raffle

Cover of Kelpie, by T. J. Wooldridge

So my plan was to return to history for this week’s blog, then I found out about my friend T. J.’s raffle, happening this week only! Read the excerpt below, and scope out the rules to win some fun prizes (and check out some nifty blogs in the meantime) Kelpie is a YA novel about a freaky fae horse. . .I can’t honestly say I was joking when I suggested to my best friend, Joe – Prince Joseph, eldest son of England’s Crown Prince – that we could probably find something the police had missed in regards to the missing children. After all, eleven and twelve year olds like us did that all the time on the telly and in the books we read…

When Heather and Joe decide to be Sleuthy MacSleuths on the property abutting the castle Heather’s family lives in, neither expect to discover the real reason children were going missing:

A Kelpie. A child-eating faerie horse had moved into the loch “next door.”

The two barely escape with their lives, but they aren’t safe. Caught in a storm of faerie power, Heather, Joe, and Heather’s whole family are pulled into a maze of talking cats, ghostly secrets, and powerful magick.

With another child taken, time is running out to make things right.

To go along with sharing the simply gorgeous cover, author T.J. Wooldridge has enlisted several of her friends who have helped her in the journey of writing this novel to put together a special treat for you!

Each day of the week, search for individual components of the cover–with a bonus piece of art on Wednesday–at these blogs. Collect the right words per the instructions, and unscramble the line of poetry to be entered to win one of three prizes!

Prize 1

A handmade fused glass kelpie necklace from Stained Glass Creations and Beyond

Prize 2

A handmade necklace from Art by Stefanie of Vic Caswell’s rendering of the kelpie from the cover!

Prize 3

An 11×16 poster of the cover of the Kelpie signed by T. J. Wooldridge and artist Vic Caswell

5×7 cards of all the cover aspects featured in the Scavenger Hunt

So, how do you take part in the Scavenger Hunt? Here are the details:

Collect the words from the novel excerpts and put together a poetic phrase.

Monday 3/25

Visit the Faery Castle at Kate Kaynak’s blog: http://thedisgruntledbear.blogspot.com/

Scavenger Hunt Goal: first sentence, 10th word

Tuesday 3/26

Hop over to Scotland at Stained Glass Creations and Beyond: http://stainedglasscreationsandbeyond.wordpress.com/

Scavenger Hunt Goal: first sentence, 12th word

Check out an artist rendition of Heather MacArthur’s family tartan with Aimee Weinstein at tokyowriter.com

Scavenger Hunt Goal: first sentence, first word

Wednesday 3/27

Bonus Art!

Meet Heather’s dad, Michael MacArthur, at Valerie Hadden’s blog: http://valeriehadden.wordpress.com/

Scavenger Hunt Goal: first sentence, 12th word

Thursday 3/28

Cast your eyes upon the kelpie, itself, with Suzanne Reynolds-Alpert at http://suzannereynoldsalpert.blogspot.com/

Scavenger Hunt Goal: 2nd sentence, 2nd word

And feel the snark of Monkey, the fey cat with Justine Graykin at http://justinegraykin.wordpress.com/

Scavenger Hunt Goal: first sentence, 3rd word

Friday 3/29:

Meet Heather’s best friend, Prince Joseph at, who’s hanging out with author Darby Karchut at http://darbykarchut.blogspot.com/

Scavenger Hunt Goal: first sentence, 17th word

And finally meet Heather, herself, who’s hanging out with one of Trisha’s editors, Laura Ownbey at http://redpenreviews.blogspot.com/

Scavenger Hunt Goal: first sentence, first word

Collect all the words and put them together in a poetic sentence, and enter them into the rafflecopter giveaway for a chance to win one of the three prizes: http://www.rafflecopter.com/rafl/share-code/MTBiNjRkMDYwN2U2MWZjNzBmNmM4YWEwNTEyODI0Ojc=/

March 19, 2013

Review: The Termite Queen: Volume One: The Speaking of the Dead

The Termite Queen: Volume One: The Speaking of the Dead by Lorinda J. Taylor

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

This book is full of marvelous science fiction elements, building not only a vision of a future academia on Earth, but also a society of termites and their distant world, and several other alien species already interacting with humanity.

I found it a compelling read, however, I also had some frustrations. The book begins with a biological expedition gone wrong: while exploring and collecting specimens, the party is attacked by a giant warrior termite. They succeed in killing it, and bringing home a smaller specimen. On the journey, one of the team leaders begins to suspect the creature is intelligent, and brings in a young linguist to study the termite in its dying hours.

The scenes between the doomed bug and its human interpreter are beautiful and moving, and they set me up to want more human/termite interactions. Alas, in this volume, that is not to be. The book alternates between scenes of Kaitrin and Gwidian, the other team leader who initially does not believe the creatures are intelligent, and scenes on the termite world, where the human incursion has caused turmoil which may lead to the equivalent of civil war.

Most of the book takes place in dialog. For a book about a linguist, that makes a certain amount of sense, but the dialog is serving every purpose: it provides backstory, exposition, conflict and even description. The trouble with dialog is that it reads in real-time, as if you are listening to a conversation. In a book consisting almost entirely of dialog, that makes it very hard to manage the pace–everything unfolds at the same rate.

Many of the conversations at the outset take place during committee meetings to plan the voyage. Some of this is vital information we’ll need in order to understand Kaitrin’s linguistic leaps–but often it’s simply too much. Also, most of the dialog is “on the nose”: it is about exactly what it says, with little conflict, tension, subtext or character development.

The author has made the choice to portray her termite characters entirely through dialog, with occasional stage directions, due to their sensory limitations. This is a choice that fits with their world, but also limits the author’s range in presenting them to the reader. The feel of these sections is almost like Greek drama. I think the effect could have been heightened by thoroughly investing in the sensory information in the human-narrated passages–showing the reader how different the two species are.

The science fiction content, especially the linguistic approach and the alien societies, is fascinating stuff and made me want to read on, in spite of the book’s stylistic flaws.

March 13, 2013

Hack Writers and Falconry: What’s the connection?

Scout, a harrier, gets his reward from Master Falconer Nancy Cowan

One of the most popular sports of the Middle Ages was falconry, the art of training a bird of prey to hunt on its master’s behalf. There are places today, like the New Hampshire School of Falconry, where you can still get a taste of this ancient sport–and let me tell you, there’s no thrill like that of having a hawk fly to your fist (even if it means clutching a dead chick in your hand to entice it).Yeah, E. C., pretty cool, but what does that have to do with being a hack? Nowadays, the term “hack” as applied to a writer, means (to quote the venerable Oxford English Dictionary) “a literary drudge. . . a poor writer, a mere scribbler.” Ouch. But the origin of the term is much older, and referred to a lifestyle of wage service, if you will, the idea that the hack was for hire for any role suitable to his or her talents (yes, the writer definition appears just above “prostitute.”)

In fact, it owes its etymology to the feeding of falcons or eyas hawks (those in training). After their capture, the birds learn to trust humans during a training period in which the bird comes to expect meals from its master, rather than hunting freely. These meals were served on a board referred to as a “hack,” probably from the earlier meaning of the word relating to cutting or chopping. “Being at hack” spread to imply other sorts of limited freedom, in which the hack was supported by others, employing his or her skills on their behalf, and not fully at liberty to choose or refuse jobs.

Before the falcons or the writers, “hack” also refers to horses for hire–an abbreviation of the word “hackney.” Hey–that sounds familiar! As well it should. A horse-for-hire broke down quickly, showing its age, and, while serviceable, became progressively less desirable the more worn-out it was. Leading, in the 1700′s, to the term “hackneyed” for those worn-out phrases so many hacks still rely on today.

March 6, 2013

Why We Love Violence

Time Magazine’s March 11 issue features a cover story about Oscar Pistorius, Olympic athlete and accused murderer. A little later on, it includes an article called “Serial Killing” about the addiction of television drama to blood. The link is the idea of a “culture of violence” in South Africa, where Pistorius felt he had to shoot first to defend himself and his (he thought) sleeping girlfriend, and in America where “The Game of Thrones” and dozens of other series build up layers of violence like an Old Master painting with oils. And we like to talk and think and act as if all of this is new, and somehow, beneath us.

A knight in the lists at a Leeds Royal Armory Joust.

But the student of history knows better. Roman gladiators, Aztec games that ended with human sacrifice, centuries of public executions all featuring jeering crowds, chanting for more. My period was no different. Executions were public affairs, intended to make a statement about the serious nature of the crime, and to warn off other criminals. Even when there wasn’t a war (rare, during the time of the Hundred Years’ War) knights participated in tournaments designed to keep them fit and leaving many wounded or even dead as a result.

Yet we like to think of Mankind as a species that abhors violence, that is only violent when pushed to extremes. We are startled and offended by our own taste in entertainment–even in an era which no longer encourages people to bring picnics to watch a battle, as they sometimes did during the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. I’ve had to face the question myself when I confront the level of violence in my writing. Why do we watch it? Why are we drawn to it? Are we all just sick and depraved, or destined to become shooters ourselves because we don’t care about our fellow human beings?

No. In fact, I would argue that violence is compelling precisely *because* we care. One of the aspects of writing, of entertainment in general, is conflict. Inherent in manufactured conflict is the question of what is at stake. As authors/entertainers, we want the stakes to be high–we want the characters to have a lot to lose, so that, if they win, the payoff is greater, and if they lose the pathos is more tragic.

When an author puts a sympathetic character’s life on the line, he is creating a rooting interest for his audience. The higher the stakes, the more excited the reader becomes. In the hands of a skilled author, an invented being of words that unspool in the mind of the reader, or of images and attitudes portrayed by an actor, takes on the aspect of genuine humanity. We watch because we worry. Because we fear for that person and want him to live. We want him to be victorious over his enemies, to vanquish his own fears and accomplish great things.

We watch the Olympics for similar reasons: high stakes competition. Someone will win; many others will lose. Even people who don’t generally like sports will watch the Olympics and track the results.

And when our hero fails–when the character dies or is defeated, when the sportsman loses, when the runner who carried our dreams has descended into a nightmare–we watch in mutual devastation. We wonder what went wrong, what choices were made or left to chance that might have changed the outcome. Because of our rooting interest, we now feel justified in having our own opinions and reactions. The criminal on the gallows deserves to hang–or perhaps is a victim in his own right. What would I have done, if it were me?

High stakes situations, in life and in fiction, compel our attention not because we revel in violence, but because we care about people. Stories that place a sympathetic protagonist at risk for great loss are inherently compelling to the viewer, and it is precisely our shared humanity that makes it so.

March 5, 2013

Goodreads giveaway for Elisha Barber!

Goodreads giveaway for Elisha Barber! Check it out–and share it with friends! http://ow.ly/incoS

Magic. . . Intrigue. . . Medieval Surgery!

England in the fourteenth century: a land of poverty and opulence, prayer and plague, witchcraft and necromancy. Where the medieval barber-surgeon Elisha seeks redemption as a medic on the front lines of an unjust war, and is drawn into the perilous world of sorcery by a beautiful young witch. In the crucible of combat, utterly at the mercy of his capricious superiors, Elisha must attempt to unravel conspiracies both magical and mundane, as well as come to terms with his own disturbing new abilities. But the only things more dangerous than the questions he’s asking are the answers he may reveal…