E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 21

March 5, 2013

Goodreads giveaway for Elisha Barber! Ch

Goodreads giveaway for Elisha Barber! Check it out–and share it with friends! http://ow.ly/incoS #magic #fantasy #medieval surgery

February 27, 2013

Werewolves in Medieval History

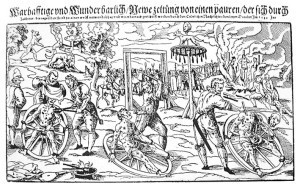

A print from 1589 shows the story of a witch/werewolf, Peter Stumpf (shown in wolf form attacking a child in upper left) who is caught and punished as shown.

Whether you’re more Team Jacob or “Werewolves of London” you know that werewolves are hot right now (both in sales, and apparently, in sex appeal). But their prevalence in the Urban Fantasy genre might obscure their long history. My eyes were opened to this history by a talk at the International Congress on Medieval Studies a few years ago, in a session promisingly titled “Hybrids and Monsters.”Gerald of Wales, in a 12th century geography of Ireland, tells the tale of a devoted and devout werewolf couple living like wolves, but with the hearts of Christians. When the wife is dying, the husband goes out at great risk to bring back a priest to administer the last rites. Some of my favorite quotes from this moving scene are when “the wolf said some things about God which seemed reasonable” and the wolf’s first words to the priest: “Do not fear.” These are also the first words spoken by the archangel Gabriel to Mary during the Annunciation, when he reveals that she will bear a miraculous child. So even then, werewolves were given a sympathetic nature.

This stands in apparent contrast to earlier views of such transformations in which the wolf represents the bestiality of the man. In the Medieval conception, the victim could become a wolf, but retain the reason and emotion of a man. The speaker, Jeff Massey, drew a parallel between hypostatis (the idea of God residing in man) with that of the werewolf (wolf residing in man). I dunno about that, but it’s interesting to think about.

The outstanding medieval werewolf appears in the Lais of Marie de France (another 12th century source) in the character of Bisclavret, a nobleman who is transformed into a wolf for three days every week. He is force to reveal this to his wife, who has her lover steal her husband’s clothes so he can’t transform back into a man. But even in his wolf form, he retains his loyalty to the king and behaves so graciously, that the king brings him back to court. After the gentle wolf attacks his disloyal wife (the first sign of violence in the beast), the truth is revealed, and Bisclavret is brough clothes so he can become a man once more.

In both of these cases, we don’t know how the good people were afflicted with their fate, but other period tales and superstitions suggest the opposite of Bisclavret’s solution: it’s not the clothes that make the man, but the skin that makes the wolf. In these cases, the werewolf, often a witch, dons a wolfhide in order to deliberately become a wolf and go about ravaging the countryside. In most cases, this results in the witch/wolf eventually being hunted down and slain in wolf form, and thereupon, transforming back. The contrast between this behavior, and that of the good wolves, who apparently succumb through no fault of their own, suggests that the beast resides within us all–and can be managed if you retain your reason. If, however, you revel in the beast, a sorry doom awaits. Wikipedia has a nice selection of methods by which men become wolves in superstitions of different lands.

I recently found a reference to werewolves in the Volsungasaga of 13th century Iceland. Also heard of an Arthurian story about a former werewolf called “Gorligon.” Do you have some good references for early werewolves? Please pass them on!

February 20, 2013

Edgar Allen Poe Meets King Charles VI: the True Tale of Hop-frog

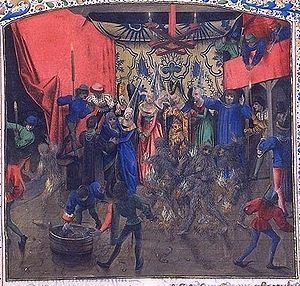

1460 illumination of the Dance of Savages

I came across the most remarkable image and tale in Barbara W. Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror, one of the foremost works on the 14th century (the “calamitous” 14th century, as Tuchman calls it.) The illustration, from a French chronicle dated to 1460, depicts a group of people covered in straw and burning, while a number of well-dressed ladies look on with expressions of pity. To one side, a lady holds another straw-clad man wrapped in blue cloth, matching her dress. If you look closely, you’ll find it is her skirt.If you are also a fan of Edgar Allen Poe, you’ve already made the dread connection. If not, you can find his story, Hop-frog as free read online. If you don’t want spoilers, well, it’s already too late, given my opening paragraph. Still, you may wish to read the tale for its particular nastiness.

In brief, the tale involves a king’s dwarf referred to as “Hop-frog” and tormented in every way. But he is known as well to be capable of devising the most marvelous entertainments. On the occasion of the story, he convinces the king and his ministers to dress as apes, in tar and straw, for the amusement of the court. While the guests shriek and run from the maskers, Hop-frog gallantly offers to find out who they are–and leans in close with a torch as if to illuminate the men. . .

But the real Bal des Ardents, or Ball of the Burning Men, was held in the court of King Charles VI of France in 1393. Charles was not well–he had been stricken with bouts of madness, and it was to ease his spirit and to celebrate the marriage of one of the Queen’s ladies-in-waiting that a ball was proposed. The court was already notorious for lavish spending and debauchery, what was one more extravagance?

Six young men, including the king, were stitched into costumes, spread with pitch and decked with hemp to give the semblance of hairy wild men. Knowing the danger, they forbade torches from the room that night. The entire Dance of the Savages had been planned by a man already known for his savagery, Hugeut de Guisay, a tyrant in his own household who used whips and swordblows to discipline those he claimed beneath his station.

The dancers capered about, howling and making obscene gestures, until the king’s brother, unexpectedly returning, entered with his entourage, bearing torches, and some of the revelers burst into flame. The queen–knowing the king was among the savages–fainted, but the quick-witted Duchesse de Berry threw her skirt over the king and saved him from the sparks. One of the others saved himself by leaping into a tub of water. As for the rest, one died immediately, two the next day, while the devisor of the scheme spent three days cursing in agony before his death, leaving those freed from his tyranny to mock at his funeral cortege.

The relationship between the historical incident and Poe’s tale is unmistakable, yet my recent research on Poe did not suggest where he might have learned of it. When he did, I imagine a dark light in Poe’s eyes as he envisioned the scene, and the tale he could make of it. I have felt that light in my own eyes more than once. History and fantasy, ever together.

February 12, 2013

Papal Resignation: 13th Century Style

So both of my papers carried stories today about the historic resignation of the Pope. Definitely big news. And both of them referred to the occasion by mentioning the last time a Pope resigned, in 1415–when Pope Gregory XII stepped down to end the papal schism (after the election of at least one Pope who had promised he would resign for that purpose–and didn’t, but that’s another story for another day). Personally, I’m fascinated by the story of Pope Celestine V, widely known as the first Pope to resign from the office. (He formalized the process of papal resignation, but was preceded by a couple of other men who were forced out of office–a somewhat different state of affairs.)

Born in 1215, Celestine lived for decades as a monk and a hermit, gaining a reputation for holiness through praying for sixteen hours a day, fasting and wearing a hair shirt–all while living in a cave. Clearly, the kind of religious figure who earned the admiration of many then as now. Alas for him, his fame as an ascetic brought him to the attention of the College of Cardinals, in a desperate search for someone virtuous enough to counteract the charges of materialism plaguing the Church.

The cardinals had been in deliberation for two years already, trying to agree on a successor for Pope Nicholas IV, who died in 1292. Celestine (then known by his original name of Pietro di Morrone) wrote an angry missive to the cardinals proclaiming that the wrath of God would fall upon them if they delayed any longer. Anyone who has ever spoken out against a logjam in any organization knows this could have only two possible outcomes: either termination, or promotion. The cardinals chose the latter, eagerly proclaiming the hermit to be the next Pope.

Fresco of Pope Celestine V at the Castle Nuovo, Naples

Pietro resisted them in vain, and finally had to be convinced by a group of cardinals to accept the position. He lasted five months. As a holy hermit, a supporter of privation, and even as the founder of the Celestine Order (an even more strict order under the Benedictine rule), Celestine was in no way prepared for the vast administrative task of being Pope. Celestine finally fled the papacy, noting his own unfitness for the office, and declaring a need to return to tranquility.

Recalled as an especially weak and ineffectual Pope, the hermit was eventually canonized for his other holy works–but he was the last Pope ever to take the name Celestine.

February 6, 2013

The Original Prince in the Tower: Arthur, Duke of Brittany

All the talk right now is of the last Plantagenet, Richard III, whose bones were identified after being excavated from beneath a car park in Leicester. You remember Richard III–the vile hunchback of Shakespearean fame who slew the princes in the tower, young King Edward V and his 9-year-old brother(or perhaps not, depending on whom you ask: learn more from the Richard III Foundation). Personally, I’m intrigued by the fact that science gives us windows into the truth of legend and historical rumor.

But today, I want to take us not merely 500 years in the past, to the time of Richard III, but almost 300 years further, to 1202, and the original bad guy of the British monarchy, King John–and the prince he dispossessed, Arthur. While Arthur was never held in the Tower of London, his fate is a clear precedent to that dread act.

An illustration of the Duke of Brittany

King Henry II had four sons, but the ones that people know by name are Richard I, the Lionheart, the second prince, and John, the youngest–variously known as John Lackland (so dubbed by his father because he had no territory to rule over) and John Softsword (for relying on a negotiated peace, rather than go to war). As these epithets imply, even in his own time, John got little respect.

The eldest prince, Henry, known as the Young King, died in 1183, during a revolt he lead against his father and alongside that most vanishing of nobles, Geoffrey, Duke of Brittany, the third son of Henry II. Are you confused yet? Stay with me–we’re down to one Henry now, and he’s mad after being trounced by his own children, but really things are just beginning to go downhill for him. King Henry II liked John best and tried to set him up for a good future, to no avail. (If you haven’t already, check out The Lion in Winter, which is an imagined history of some of this mess.) Geoffrey died in a tournament, leaving two children, and sticking his father with choosing between the popular Richard and John. Richard, of course, was given the crown.

According to some sources, Richard actually named his brother Geoffrey’s son Arthur as his heir in 1190. What we do know is that the young Arthur, Duke of Brittany, had the support of the powerful French ruler, Philip Augustus, and the nobles of England’s French holdings. On his deathbed, Richard declared John to be his heir instead, leaving John with a problem: a declared successor, popular with a large number of powerful people. Arthur at first declares himself a vassal of France, receiving lands and support, but when he was disenchanted with Philip, he fled to John. That didn’t last–he got wise to John’s own ambitions and returned to his own seat to raise an army against John, but John and his barons managed to surprise the young duke and captured him.

What to do, what to do? For a few months, Arthur was imprisoned in one castle, then another, and rumor has it that John wanted him mutilated, but his keepers refused. Both men must have known the situation was untenable: John could not effectively rule while Arthur lived. Few would have been surprised when Arthur vanished in April 1203. His jailers are repeatedly said to have feared to harm him, and so the legend has come down to us that it was King John himself who did the deed. According to the Margam Annals, a contemporary chronicle, a drunken John slew his nephew, slung a stone about his throat, and tossed him into the moat at the castle of Rouen. A fisherman found the corpse in his net and, fearing this knowledge, sent the duke to be secretly buried at the priory of Bec.

Was Richard III responsible for the deaths of his nephews? Perhaps one day, science will provide that answer as well. But if so, he was merely one in a sad chain of precarious monarchs, clinging to the crown through the murder of kin.

January 30, 2013

Great Characters of the Middle Ages: Rahere, Hospital Founder and King’s Fool

This is the second in an irregular series of the unsung heroes, villains, and fools of the fourteenth century. You’ll notice as the series proceeds that there’s a lot of crossover between these categories, but none makes that so clear as the story of Rahere, companion and fool of King Henry I of England–and founder of St. Bartholomew the Great, which still stands in London today, along with the hospital of the same name.

![tomb of Rahere, in St. Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield, London. Photo by Mike Quinn [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1388563164i/7870569.jpg)

tomb of Rahere, in St. Bartholomew the Great, Smithfield, London. Photo by Mike Quinn [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

According to the few sources we have, Rahere was born to a poor family, but had such a cheerful nature that he made friends easily, and soon had joked his way to the court of Henry I, the son of William the Conqueror, where he accompanied Henry in most of his travels, perhaps formally taking on the role of jester. However, his good humor apparently concealed great depths, and he may have been influenced by the pious Queen Matilda to look for a greater purpose. He may also have been inspired by the sinking of the White Ship in 1120, in which Henry’s heir was lost along with other members of the royal family.

Repenting of his trivial life at courty, Rahere resolved to make a pilgrimage to Rome, where he visited many of the great churches to pray and seek forgiveness. In the vicinity of the church of San Bartolomeo, he was struck ill, perhaps with malaria, and was near death. In his fevers, he made a vow that, should he survive, he would found a hospital to minister to the poor. His health improved, and he headed home for London. On the way, a vision seized him in which Saint Bartholomew told him that he had chosen a location for the hosptial and a church besides. At the time, all hospitals were religious institutions in any case, so this was no great surprise–although the vision made a big impression on the fool.

At home, he asked for the king’s permission to use that part of the Smithfield market to erect the Priory and hospital. It was chartered in 1122, and finished by 1127, to be dedicated to Saint Bartholomew. Rahere himself became the prior until his death in 1343, and was buried in the church he had founded. The elaborate sculpted tomb, complete with effigy, was not built until a remdoeling in 1405.

Priest, prior, visionary. . .and fool, Rahere remains one of the most interesting characters I’ve come across in my research–and I’m pleased to help spread his curious tale.

January 23, 2013

A Brief History of Bastardy

One of the difficulties I’ve had in writing a series set in the fourteenth century is the dearth of appropriate insults. Many of the “fighting words” of today had different meanings back then, or were not used in a pejorative sense. I first noted the problem in my blog, Curse you, Shakespeare!

But today, I’d like to go a little further in-depth, with a history of the bastard.

We know that marriage was important during the Middle Ages, but the period is also rife with nobles, especially kings, princes and dukes, who have a large number of acknowledged children out-of-wedlock. The practice was, if not encouraged, not especially punished either. There are even a fair number of clergymen with acknowledged bastards of their own, and Barbara Tuchman, in A Distant Mirror, noted that, of 614 grants of legitimacy (ie, to legitimize an extramarital birth) in 1342-43, 484 were to members of the clergy. So there was a system of recognizing these children and no particular stigma to being one.

There was even a heraldic symbol used to denote bastardy on a nobleman’s Coat of Arms, typically a “bar sinister” meaning a stick that crosses the shield to the left (“sinister” in Latin). You can see what I mean on the Arms of the Duke of Grafton, one of several illegitimate sons of Charles II. These guys couldn’t succeed to the throne, but Duke isn’t too shabby. Likewise, the duke formerly known as “William the Bastard” has come down to posterity as “William the Conquerer”.

So when did the term enter the lexicon of insult? The OED notes the first figurative use of the term in 1583, to describe someone who was not literally a bastard. However, there are earlier references to its use to describe something as “mongrel, hybrid, or inferior breed” (1398) so it seems likely the crossover from an adjective for something of mixed parentage, to an insult, comes from that direction. The word first shows up in the historical record in 1297, as either a noun or an adjective. After about the 1500′s it pops up all over the place, to describe anything that might be a combination of disparate items.

The OED gives its origin as Spanish for something like “pack-saddle child,” while a few early Modern period dictionaries try to deduce specifically pejorative origins, for instance, from the Dutch for having an “abject nature” or from the Anglo-Saxon for base origin.

So it seems that, not long after it starts to be applied as an insult, the writers of the time are trying to justify that use. Just as I would like to justify it now, for my own purposes. Some things never change.

January 16, 2013

Review: The Blood-Dimmed Tide

The Blood-Dimmed Tide by Rennie Airth

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

I so enjoyed the author’s first novel, The Dead of Winter, that I jotted his name on a paper and stuck it to my bulletin board to keep an eye on him. This second John Madden mystery/thriller took so long to appear that I had stopped looking–but I pounced the moment I saw it, and will look forward to finding the third as well.

I said “mystery/thriller” above, but it’s really a thriller. In a writers’ workshop years ago, I heard the distinction made that, in the thriller, you know who the villain is–you may even be in his point of view sometimes–and the key is stopping him. In a mystery, OTOH, you read to discover the villain, and he is usually introduced among the cast of characters at the very start.

This book starts as a mystery, but narrows down to a very intriguing and problematic suspect range. Suffice it to say, identifying the guy requires international cooperation between England and Germany, just prior to the Nazi takeover. Interesting political territory. It also introduces a young German policeman whom I’d like to read more about.

I admire the way that the author handles point of view to reveal his protagonist, who is naturally reticent, as well as building suspense: I really did not want to put this book down in the last quarter.

However, I’m a bit concerned about how the author is handling his historical setting. It has the potential to create useful tension between the reader and the work, because we know what is about to happen in Europe, and the characters don’t–but instead of allowing that tension to develop naturally, the author sometimes pushes too hard to be portentous. Also, he has a psychologist character who seems to be an FBI profiler in disguise, and decades before his time. I wasn’t sure that was necessary. I know this character appeared in the first book, but I don’t recall being as bothered by his information as I was this time around.

On the whole, however, this is a great read, riveting and psychologically engaging.

January 2, 2013

The Next Big Thing Blog Hop: Elisha Barber

cover image for Elisha Barber, from DAW Books, cover by Cliff Nielsen

I was tagged to participate in The Next Big Thing Blog Hop by the marvelous Heather Albano, author of two (so far!) steampunk novels you can learn more about at her post: http://www.heatheralbano.com/2012/12/26/the-next-big-thing-blog-hop/

So without further ado:

What is the title of your book?

Elisha Barber

(book 1 of the Dark Apostle series) coming out July 2, 2013 from DAW books.

Where did the idea come from for the book?

I was actually researching medieval medicine for a chapter in another book I was writing—and I ended up diving down a research rabbit hole, reading a dozen books on the subject. One afternoon when I was meant to be writing something else, I suddenly envisioned a character, with a problem. Then I knew I had a whole new book on my hands.

What genre does your book fall under?

Historical fantasy.

Which actors would you choose to play your characters in a movie rendition?

GAH! I hate this question! HATE IT! sorry. I’ll try to get over it. I think the reader should envision whom they wish when they read the book based on my descriptions, and their impression of the characters overall. However, I will grant you that my protagonist, Elisha, has long, black hair and blue eyes (rather different to how he appears on the cover, although the overall build and attitude are spot-on).

What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book?

In 14th century England, a barber surgeon learns diabolical magic to defeat an unjust king—but the cost may be more than his soul.

Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency?

The book comes out with DAW (which is part of the Penguin publishing family).

What other books would you compare yours to within your genre?

Currently? People who enjoyed D. B. Jackson’s Thieftaker (magic and mystery in pre-Revolutionary Boston) are likely to enjoy this. For the *Not actually historical, but they feel that way*, check out the work of Carol Berg.

And if you are looking for something excellent that has unjustly vanished from the shelves, look for R. A. MacAvoy’s Damiano series: conjuring spirits in medieval Italy.

Who or what inspired you to write this book?

As noted above, it began with researching Medieval medicine, and surgery in particular. I also read up on beliefs about historical witchcraft, and was dismayed to find, over and over again, references to “heretics, witches, Jews and homosexuals” all lumped together as undesirables—the first to burn when the stake goes up.

One of the books I read about torture featured page after page of contemporary—not historical–examples, so I was responding to a sense that injustice has persisted through history, that humanity has grown more numerous and more capable of inflicting pain and humiliation—when we should have been developing the means to stop it.

What else about the book might pique the reader’s interest?

This is a fast-paced and emotionally engaging work for people who are interested in the fourteenth century, in historical medicine, or are simply looking for a damn good story with a protagonist you’ll be rooting for.

I tag these authors to write about their book next Wednesday:

Travis Heermann, author of military and adventure fantasy, at http://www.travisheermann.com/ where I see he’s also starting a YA horror/fantasy series.

Aussie fantasy author Alison Strachan, http://writingmytruth.com/ whose tagline is “Write from the Heart. Write what Scares You Most & Read with Hunger.” We were connected by mutual friend, Lorinda Taylor, of Termite Queen fame, and I’ll be looking forward to her answers!

December 26, 2012

Deleted Scenes and Settings: St. Catherine’s Oratory, Chale, Isle of Wight

Every so often in my research I come upon a place or an idea so compelling that I must learn more. Some of these places eventually become scenes, and some of those scenes, alas, end up on the cutting room floor. So it was when I researched the Isle of Wight for a few chapters in the Dark Apostle series.

The place, St. Catherine’s Oratory, a 14th century lighthouse high on a bluff in Chale.

The lighthouse tower, all that remains of the 14th century St. Catherine’s Oratory.

Image Copyright Chris Downer and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

The Oratory was built William de Godeton, Lord of Chale, as penance for an act of plundering. Apparently, he looted a good deal of wine off of a sinking vessel–wine that was meant for a monastery. To avoid excommunication, he built an oratory (a small church) with rooms for a single priest to say prayers for the souls of those lost at sea, and to tend the fire in the tower above. Theoretically, the light would ward off other ships from meeting a similar fate.

Building began around the time of the trial in 1313 and was completed in 1328, shortly after de godeton’s death. The lighthouse remained in use until the Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII. The oratory eventually fell, but the tower remains, rather too far inland to serve as a useful lighthouse, and often shrouded in mist in any case. A new lighthouse was begun nearby in the 1700′s, and never finished. (The tower above is referred to by locals as “the Pepperpot”, leaving its unfinished companion to be called “the Salt Cellar”). A very new (by my standards) lighthouse stands below, on the edge of the sea, in a much more effective location for preventing shipwrecks.

As a setting for a novel, this place is hard to beat. It’s got a fascinating history, a great view, and plenty of atmosphere–it even stands next to a Bronze Age barrow! And the scene that I wrote incorporated all of those elements. Note, I did not say plot advancement, great dialog, or character develpment. . . so, alas, it had to go. But I keep some images of St. Catherine’s Oratory in my files, just in case.