E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 10

October 16, 2015

A Brief History of the Inquisition: The Original Thought Police

When I was playing more actively with the Society for Creative Anachronism, I had a Jewish friend with a Spanish persona, circa 1492. He used to joke that, contrary to Monty Python’s claims, he *did*, expect the Spanish Inquisition. . . any day now, in fact.

A print of the spectacle of execution.

Thanks, in part, to those Monty Python boys, the Inquisition has gotten a particularly sinister reputation, making it hard to disentangle the reality from the representation of the Inquisition, and to examine how it manifested in different times and places.

The history of the inquisition begins around the 1200’s, with the desire of the Church to seek out and correct heresy, in particular, the Cathars of Southern France. In order to be a heretic, one must be a member of the Catholic Church–Jews, Muslims, etc, are not heretics, and thus are not ordinarily subject to the inquisition. (unless they convert or claim to have done so). When Ferdinand and Isabella instigated the Spanish Inquisition, they focused more on Jews who had converted to Catholicism (conversos) and on Judaizers (those suspected of Jewish sympathies or beliefs).

The use of torture by the various inquisitions was authorized by Pope Innocent IV (scroll down for a pdf of the translated bull) in 1252, following the murder of a papal legate by a group of Cathars, but it requires the inquisitor to be certain of the evidence presented by witnesses against the accused, states that torture should be used only once, and could not cause damage to life or limb. However, inquisitors were known to claim that the next day’s torture was really just a continuation and shouldn’t count as a second session. . .The bull (referred to as Ad extirpanda) also gave local rulers oversight of the inquisition in their territory.

Most inquisitors were drawn from the ranks of the Dominican Order, the so-called Blackfriars. This role gave rise to the apocryphal claim that their name derives from Domini canus, or Hound of the Lord. (In fact, the name comes from Saint Dominic de Guzeman, the founder of the order.) Franciscans were sometimes also involved.

When someone was accused of heresy, that individual would be brought to give testimony, along with whatever witnesses made the claims. If the individual were found to be an unrepentant heretic, he or she would be turned over to the secular courts for justice, which might range from a prison term (most common) to being burned at the stake (rare–but fearsome). A large part of the purpose of punishment was to serve as a deterrent to other potential heretics, hence the most harsh sentences. Their lands and good would be seized, no doubt leading to many false accusations by people hoping to profit from their neighbors’ downfall. Something similar happened in New England’s own witch craze, where the accused often stood to gain materially from the convictions of others.

The Spanish Inquisition, that most dreaded of institutions, may have led to the deaths of 3000-5000 people over the course of its 350 years in existence according to some sources (though they don’t state a source for their numbers). One researcher counted 44,674 trials and only 826 executions. Researcher and author Cullen Murphy gave an Inquisition FAQ on the Huffington Post a couple of years back with some different estimates.

Those who repented of their supposed heresy could escape punishment altogether–but must be wary lest they relapse, and draw a stronger judgement. Remember, the inquisitions, though founded by the church, were under local control, and it was the secular court that imposed punishment. While they were established to root out the supposed threat of heretics drawing souls away from God, these local inquisitions persisted and were often wielded as political rather than religious instruments of control.

The Spanish Inquisition executed its last victim in the nineteenth century, and the Roman Inquisition was officially ended a bit later. The concept of an inquisition as a powerful force rounding up and ferreting out unbelievers moved from the historical usage into a lingering symbol of the abuses of power–especially when the organization exists to destroy intellectual opposition, anyone’s word could be taken as fact, and there is no check on the authority of the few.

October 2, 2015

Heretics, Witches, Homosexuals and Jews: A history, and a present, of persecution

One of the reasons I started writing my Dark Apostle series was the number of times that this list appeared during my research. It is the historical equivalent of someone saying, “Round up the usual suspects,” whenever anything goes badly wrong. I wanted to question some of these overlapping categories of persecution. The research led me to some surprises about the assumptions we make about the Middle Ages, as well as to some surprises about the ways we think now.

An early tag line I considered for the series was: What do Witches, Jews and Homosexuals have in common? When the stake goes up, they are the first ones to burn. Sadly, they still are–although there has been less interest in the persecution of pagan religious practitioners of late, at least in my awareness.

One of the first big reviews I got for Elisha Barber chastised me for making Elisha too modern because he fails to be homophobic, but did not remark upon the fact that he also fails to be anti-Semitic. During the period in which I’m writing, anti-Semitism was much more rampant and virulent than homophobia. Still, the origin of the slur “faggot” is a reference to firewood originally applied to heretics.

I chose to frame Elisha as centered in his medical knowledge: that all men are the same beneath the skin, and his task is to heal them as best he can. He is dismayed to discover the overlapping prejudices of the various groups he encounters. So, when his mentor, Mordecai, a Jewish surgeon, is injured, some of the witches refuse to help, in spite of the fact that they, too, represent a persecuted minority.

This paranoia about groups perceived to be different increases when the dominant culture feels increasingly insecure. So during the Black Death (referred to prior to the 17th century as The Great Mortality) struck, the rumors flew–mostly about Jews and all of the hideous and horrible things they were said to have done to bring about the disease, none of which were remotely true.

However, they were the primary money-lenders of the time (thanks to that line in the Bible about how Christians shouldn’t make money off loans to other Christians, and to the fact that they were, in most places, so limited in the professions open to them). It’s pretty convenient, when looking for a scapegoat, to point the finger at the people to whom you owe money, thus making your debt vanish. Phillip the Fair of France did something similar when he accused the Templars of heresy, and thus claimed their lands and property.

Both the Templars, and some leading Jews, when tortured, admitted to all sorts of terrible things to make the pain stop. These confessions provided “evidence” that the accusations were true. Even in the Middle Ages, it was widely known that torture rarely produced what we would term actionable intelligence. While torture sometimes does produce bits of truth, they are often mixed with falsehoods and inventions, either deliberately, or in a panic. People under enough stress will say anything to make it end.

And by now, you will have noted certain similarities to current events, and to events around the time the series began. Because when I started looking into the history of torture, which many of my characters might have faced, most of the information I found was, in fact, contemporary. The images from Abu Ghraib were coming out, and later on, the report about possible torture perpetrated by the US government. At the same time, hate crimes against randomly selected people said to represent some reviled group or another cropped up across the nation, and around the world. Just today, I saw a news blurb about a Muslim man dragged from his house and beaten to death because his Hindi neighbors had heard a rumor that he had killed and eaten a cow. Rumors and lies. Would he have confessed, if he thought it would make them stop?

Just as many of these same prejudices and accusations are being floated in the world today, some people seem determined to add groups to the list, rather than abolishing the list. Muslims, immigrants, refugees, Sunnis or Shi-ites, African Americans, police officers, Liberals, Republicans. . .

The Nazis placed gypsies and Catholics alongside Jews and homosexuals on their list, and I came across another article about someone casting acid on gypsies in Scandinavia, which is often considered a bastion of rationality and non-violence.

The more I studied history, the more it became clear that the old saw about history repeating itself is true. Humanity rumbles on toward the future, clinging desperately to the reactions of the past, the biological distrust of the other which is ready at any time to burst into flame.

One reason I write fiction is to imagine a world where we could do better than this, where hatred would be of an individual who had wronged you, rather than a category of people who have done, and mean, no harm. Where accusation, arrest, interrogation and prosecution would be based upon an examination of the facts–and the process would be halted and abandoned if the facts did not support conviction. I would like to imagine it could be this world.

A curious ray of hope, then and now, comes from an unexpected direction: a pope, the leader of the Catholic Church, speaking out for tolerance. Will Pope Francis make a difference? It’s hard to say. During the time of the Templars, Pope Clement V tried to resist the persecution, but eventually surrendered to the will of the king. During the Black Death, Pope Clement VI wrote a bull demanding that his followers stop persecuting the Jews, and he allowed Jews to settle safely in Avignon. So the track record of papal tolerance is rough, but could lead somewhere. (more about the Inquisition on another day. . .)

Perhaps my work is, after all, escapist. I frame a narrative of humanity striving for dignity in a setting of darkness, despair and danger. Because, all too often, the Middle Ages seem much more inviting than today.

September 10, 2015

Skulls and Cross Bones: the Medieval Ossuary at Hythe

I’d like to introduce you to the beautiful Norman-era church of Saint Leonard’s at Hythe. This small, seaside town is about midway between Hastings and Dover, just enough off the beaten track to get few visitors. The church is also the reason I selected this particular location for certain events in Elisha Rex. For one thing, Saint Leonard is a patron saint of prisoners, a key theme in the book. And for another thing. . . there is the crypt.

St. Leonard’s at Hythe, exterior

The church is not especially well marked, but we found it along the winding streets, and were able to go inside. It turns out that the crypt is only open certain times during the off-season (we were there in November), and the rector did not answer his doorbell. However, we heard sounds from above, and waited by the tower door until two bell-ringers emerged from setting up for the Remembrance Day service. One of them, the friendly and fascinating Nigel, offered to let us in, then go find one of the trustees, and so I found myself in the basement of the church with its many inhabitants.

England, unlike some other parts of Europe, is not known for its ossuaries. Most bones are either buried in graveyards, or in barrows during earlier times, and no one is quite sure how the ossuary at Hythe developed. It seems that the bones had been exhumed from earlier graves during expansion, and stored. This storage may have been intended as temporary when it first began, but by the 14th century, the bones had been ensconced in their place, in stacks by type, but with the occasional, dare I say decorative? flourish, like the skull tucked in among the humerus bones above. The collection includes about 1000 skulls, and probably represents between 1500 and 2000 individuals.

some of the many skulls, neatly arranged

While the bones are rumored to have been those of slain pirates or other invaders, a large number of them belong to women and children. They were probably Hythe residents exhumed when the church was extended in the 13th century. Nowadays, the collection has been examined to reveal signs of disease, tooth-decay and aging, and various other osteological studies.

The ossuary is a valuable resource for historical study–and a fantastic setting for my barber-surgeon who may be drifting too close to necromancy.

September 4, 2015

Reading like a Writer

One of the dangers of crossing the line from reader to writer is that it changes the way you read. For me, it makes me impatient with bad style, slow starters, lack of tension and plot holes. I am much more likely to drop a book than to keep reading if it’s not grabbing me. There’s just not enough time to read bad books–or even mediocre books you’re not enjoying. But I am also much more likely to delve into the question of *why* it’s not working. What has the author done or failed to do that is causing my departure?

But reading as a writer is also a great asset in considering how to improve my own work, or learn a new technique. In this case, I turn to a book or an author who’s doing a good job. When I want to learn more about the writing craft, or to study the work of someone I admire, then I approach it as a research project. What can I learn about the people who are doing it well?

Right now, I’m working on a thriller novel, my first entry into that genre, so I’m reading and listening to more thrillers, thinking about how they are constructed, what makes a good one, what I enjoy and what I hope to do for my readers. At the moment, I want to know how authors introduce their series characters. How do you make a character who will capture the reader’s imagination, and keep it for a series of books? To that end, I purchased copies of the first volumes of several series I admire, and I am examining their openings one by one. In order to analyze them rather than get carried away by them, I start by re-typing the first few pages. This makes me pay attention to the word choices, verbs, descriptors, sentence construction and order of details.

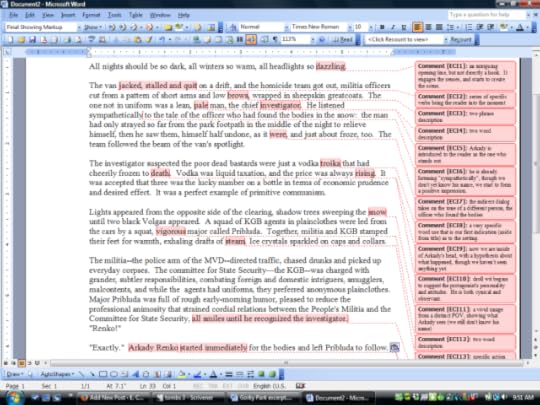

I started with Gorky Park, by Martin Cruz Smith, which introduces Chief Investigator Arkady Renko.

a screen shot of Gorky Park’s first page, with my commentary

Before we even learn his name, we are given an image of Renko as set apart from his companions (lone wolf–already intriguing). He is described as “sympathetically listening” to another officer, an appealing trait. As we sink into his point of view, we find a cynical sense of humor. The KGB appears next–and because we are (mostly) Americans, we are instantly on the alert. The lead KGB officer comes across as too jovial, and it is this character of whom we are already suspicious who introduces the protagonist, by losing his smile and shouting his name. A sympathetic lone wolf strong enough to have enemies in the KGB? I’m hooked.

Interestingly, Smith starts to lose the bond he’s established between the reader and the protagonist a few pages later, when less appealing traits seem to be emphasized, and the characterization feels inconsistent (We are told he smokes cheap cigarettes when faced with the dead–another point in his favor, this small flaw, but soon he is chain-smoking all the time, which makes me doubt the author. While he is initially shown as sympathetically listening to a subordinate, he becomes abrupt, and at one point abusive to a degree that seems unnecessary). Later books in the series maintain a more clear image of Renko as a man of action, perhaps fatally flawed by his refusal to abandon even the most difficult and personally challenging case. But that initial grab is what I’m looking for–a character the reader admires and wonders about, one with a balance of clear action, attractive traits, and humanizing flaws.

How about you? What attracts you to a character? What would you like to see on page one that will make you want to know more?

August 27, 2015

Sasquan World Science Fiction Convention report

Yes, I am back from Spokane, glad to escape the land of the red sun, to rainy New Hampshire.

Smoke from nearby wild fires gave the city an apocalyptic feel.

At the con, I enjoyed talks by Ken Liu and Kate Elliot about world-building, sparking some new ideas for my next project: epic, historical, Asian–all the good stuff. I also attended the conversation between George R. R. Martin and Robert Silverberg, where they talked about the history and future of the genres and of Worldcon itself. Steven Barnes led two sessions of Tai Chi, which, with him, is part inspirational gathering and part exercise, and always worth the visit. I attended a talk by James C. Glass about Australian Aborigines as the first astronomers, which was fascinating, and went to one on Imposter Syndrome run by Crystal Huff (highly recommended if you suffer from this).

Here are some favorite quotes:

“Growing old is like making ice sculpture in the desert. There is less ice every day, but if you get a little bit better at sculpting every day, you can still make something great.” Steven Barnes

“The internet makes it too easy to say stupid things and multiply them indefinitely before you can call them back.” Robert Silverberg

“The idea of the nation-state was created out of iron and blood.” Ken Liu

This year’s much-anticipated Hugo Award Ceremony was very enjoyable, with both hosts and recipients keeping the mood light and focusing on the community of science fiction. Wired magazine had a great article about the event and the results. I like to attend the ceremony in part because (like GRRM and Robert Silverberg) I can imagine myself up there some day, and in part because of that sense of community–the anticipation of a few thousand fans sharing the excitement of what is to come.

My own events were a lot of fun, especially the panel on Learning to Love Your Deadline, wherein I tried to remember if I had ever missed a deadline in my publishing career (causing Patricia Briggs to look for a heavy object with which to bludgeon me–thankfully, nobody had a hardcover handy). It was great to see some new faces at my reading as well, and I think I gave some useful feedback to three new writers at the Writers’ Workshop.

Outside the con, a group of artists worked feverishly to repair and refresh these amazing lanterns for the Chinese Lantern Festival–wire frame creatures with lights inside and brightly colored fabric outside, an intriguing process to watch. And where else but Spokane can you feed raw meat to tigers?

A tiger gets a treat from a guest at the Cat Tales tiger rescue center.

August 14, 2015

Goodreads review: Medieval Ghost Stories by Andrew Joynes

I discovered this book on the recommendation of a scholar who presented a paper about revenants (roaming dead) in Medieval England at this year’s Kalamazoo Medieval Congress. Since this is a topic near to my heart, in more ways than one :-) I picked up a copy at the publisher’s booth.

This book gives some great insight into the role of the supernatural in the lives of people around the turn of the first millennium, up to the 1300’s. It is well-organized by topics including: Ghosts and Monks, Ghosts and the Court, The Restless Dead, and Ghosts in Medieval Literature. Each of these sections includes a general introduction, placing the manifestation in context, then a series of excerpts from period works–chronicles, sagas and stories–that describe what happened and to whom.

As a fantasy author, and also as the leader of teen camps where I am frequently called upon to tell horror stories, this is just the kind of material I keep an eye out for. It includes some more familiar pieces, like the werewolf Bisclavret from Marie de France or a tale from Boccaccio’s Decameron, but also many other works from less known sources–local chronicles and the like.

Most of these stories take place on the cusp of the Christian emergence, as local populations settle into the expanding religion, and are given a theological spin by their authors (frequently priests and monks–the most educated people of their day). So we hear souls tell of the torment they suffer because of their sins, and we see Guinevere offer to have masses sung for the restless spirit of her mother. These spirits are often laid to rest at last by the intervention of priests or of proper Christian burial.

To me, the most interesting narratives here are those from the Scandinavian sagas, where Christian motifs overlay a local aesthetic. Hence a woman wronged in life whose corpse is being brought to a monastery for burial to atone for the wrongs done her rises up in the night to make a meal for her funeral party because the miserly host has not done so–thus chiding the host for his failure to provide hospitality due to guests.

Although eager to find Christian meaning in stories of ghosts or the walking dead, Christianity in general had an uneasy relationship with the entire concept. The dead, according to doctrine, lay quietly to wait for judgment, if they were not already taken up, or sent down. The body was not animate of itself, and the soul had already been accounted for–so Church fathers are often at pains during this period to insist that ghosts and revenants simply didn’t exist, even as many laypeople accepted the stories as the proof of Heaven or Hell–because these spirits desired to reach the one, or to speak out in warning about the other.

But there is another category of stories, warning the living to make much of life–and especially of love, in which groups of wandering spirits are show as joyous or as despairing in proportion to their willingness to share love while they were alive, bringing to mind later works, like Andrew Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress.” Suggesting that man’s fascination with the dead, and his willingness to use them as examples to the living, whether for instruction or seduction, goes on.

August 7, 2015

Sasquan is coming! See you at Worldcon?

In a little over a week, I’ll be in Spokane, Washington for the annual World Science Fiction Convention, this year entitled Sasquan.

I’m a bit of a convention junkie. I enjoy meeting and mingling with other writers as well as meeting fans and readers–ideally introducing new readers to my work. I always come back feeling fired up about writing, and about the science fiction and fantasy genres. This year’s worldcon promises to be especially stimulating for a variety of reasons.

I’ll be mentoring as part of the writer’s workshop (for which registration is closed–sorry–but look for it next year!). You can also find me at these events:

Kaffee Klatche – E. C. Ambrose

Thursday 13:00 – 13:45, 202B-KK3 (CC)

Join a panelist and up to 9 other fans for a small discussion. Coffee and snacks available for sale on the 2nd floor.

Requires advance sign-up–please join me!

Learning to Love the Deadline

Thursday 15:00 – 15:45, Bays 111B (CC)

Deadlines – love ’em or hate ’em? Are they different depending on the length of your project? Are they different depending on whether you’re writing fiction or non-fiction? Can the deadline make you a more disciplined writer?

Reading – E. C. Ambrose

Friday 16:00 – 16:30, 303B (CC)

And I will be minding the Science Fiction Writers of America table for a bit, probably on Wednesday, as well as autographing there on Sunday. Times TBA

July 25, 2015

The Faithful Hound

This week, I had to say goodbye to a dear companion, but this isn’t really a personal blog, so rather than eulogize Jordi directly, I thought I would talk about just a little of the history of the faithful hound in the Middle Ages.

Jordi in happier times–he was always happiest in winter.

Dogs are often viewed as symbolic of loyalty, which is why they appear at the feet of knights on their tomb effigies. There have long been stories of dogs who linger on their master’s graves, or, nowadays, who wait fruitlessly at the train station for masters who do not come home. Hereward the Wake, the famous hero of Ely who fought against the soldiers of William the Conqueror, until he drained the fens so the Wake could no longer escape, was said to have had such a hound.

This kind of loyalty can also be turned against the hero. According to some sources, Scotland’s King Robert the Bruce possessed a devoted mastiff who had to be left behind at the manor when Bruce was on the run from the English in the highlands. Some clever Englishman got the idea of taking the dog with them, and using it to track him down, knowing that the dog would pursue its master with great delight until they could be reunited, but a Scottish sympathizer let the dog go rather than see this love subverted.

In France during the 13th century, a cult rose up around the grave of a greyhound venerated as Saint Guinefort when certain miracles were said to occur at the site. The dog had been martyred by its own master when it defended a child from a wolf, only to be taken by its bloody mouth for the aggressor. The knight who owned and slew the dog grieved mightily over his error, and buried the dog with great solemnity. Naturally, the Catholic Church did not approve of a canine saint (no matter how many people then and now believe in the divine nature of the dog), and repeatedly tried to discourage its veneration.

The fact that a character even owns a dog, or that dogs love him, is often used by contemporary authors to show that someone is worthy. If such a creature loves, it is thought, then the master must be worthy. I suppose I am guilty of this myself, with the relationship between the exiled Prince Thomas and his deerhound Cerberus in Elisha Magus. When the dog accepts Elisha, too, he uses this as evidence that he is worthy of trust.

Elisha held out his hand to be sniffed. Gravely, Cerberus pushed his wet nose against Elisha’s fingers, then gave him a single, long slurp, and lay down at his master’s side.

Casting a quick look at the dog, the prisoner turned as quickly away, his eyes shining. “What have you done to my dog?” he whispered, his voice cracking. “You’ve cast some accursed spell on him.”

At that, Elisha laughed, shaking his head. He had gotten a fright from that knife brandished against him, but, try as he might, he couldn’t see the danger now. Here was a man loyal to his king, seeking justice as he saw it, heartsick because his dog seemed to have deserted him. Letting go his irritation, Elisha said, “It’s nearly impossible to cast a spell on a being with willpower of its own. All I did was try to help him, to make him comfortable, nothing more. If that’s a spell, I believe it’s commonly known as kindness.”

Cerberus returns in Elisha Rex, as, alas, my own dog cannot. But his spirit is echoed there, one of a long line of faithful hounds.

A knight at rest in Ely Cathedral, with a small dog as his companion.

July 17, 2015

Heroes and Antiheroes: The Integrity of Prince Hans

This past weekend, I had the pleasure of attending the Readercon convention for science fiction and fantasy literature in Burlington, MA. One of the panels was about heroes versus antiheroes: what makes the difference? How flawed must a hero be to swing to the antihero side? How about pushing all the way to villainy? After all, most people are the heroes of their own story, whether or not they seem evil to others.

Prince Hans, from Disney’s Frozen

It occurred to me that this is one of the reasons I enjoyed the recent Disney juggernaut “Frozen.” I’ve written before about the world-building, but it’s really the take on character that I appreciated most. The characters make and solve their own problems. They pursue their own goals (love, freedom, kingdom) with clear intent and enthusiasm. And Prince Hans is right out there, using different tactics to gain the leadership role he seeks.

The last of many brothers, he has no chance for such a role in his own kingdom of the Southern Isles. In the middle ages, spare sons might go to war, be given lesser positions in subservience to the heir, or even enter the church as another means of advancement. Hans wants none of this. So he travels to a distant realm, probably with the thought of meeting and marrying Queen Elsa. Instead, he meets her little sister, so desperate to be loved that she falls for him right away. He’s adept at fostering a connection with her, and thus, with the crown.

When Elsa freezes the kingdom and Anna rides of after her, Hans is given his big chance to prove his leadership, and he does so in spades, distributing blankets and needed supplies, opening the palace to nurture the citizens (in a way it has not been open for years). He collaborates with officials of the kingdom, as well as with its allies, and in every way shows himself to be an able administrator, and likely, a worthy king. When he brings Elsa back to face justice, he is not wrong: it is her power that has cast the kingdom into a possibly irrecoverable state, and it may be the only course to kill her.

We are encouraged by our sympathy for Elsa, built mainly through her relationship with Anna, to view this decision in a negative light. But if Elsa had not been able to balance her power and restore the kingdom, what alternative would have remained? Sure, I understand her urgency to escape from her prison, but what are the other choices for the kingdom, frozen by her magic? The idea of magic dying with the one who cast it is common in many magical realms–we don’t know if that limitation exists here, but it’s not unreasonable. Thus if Elsa neither removes the curse (Anna’s solution), nor dies (Hans’s solution), the kingdom will be ruined–and possibly many lands beyond. We don’t know how far the freeze extends.

Hans can thus be viewed as an antihero, taking actions in pursuit of an important goal (saving the kingdom, clearly heroic), but actions that will have a negative impact on at least one other character we have been led to care about, Elsa herself.

His refusal to kiss Anna is a bit more problematic. He knows that he doesn’t love her, and thus cannot save her. Honestly, little harm would have been done by his kissing her anyway. They could both have been heartbroken and confused about why it doesn’t have any effect, and she dies in his arms (exactly as he later claims she did). He could also have refused to kiss her as an act of personal integrity, knowing his “love” cannot save her, and thus refusing to succumb to that hope or allow her to do so.

But this is a Disney film, and, in spite of its unconventional approach to ideas of heroism, true love, and sacrifice, it can’t really go there–leaving the viewer with the impression of Hans as merely an ambitious young man, working to secure his goal. He does ask Elsa to bring back the summer, and she refuses, leaving him no alternative.

It’s interesting to view Hans as a person of integrity, having come very close to achieving a kingdom, and now doing his sincere best to work in its behalf, willing to make himself unpopular by killing the queen in order to save the kingdom. Any decent lawyer could get him off the charges, simply by pointing out that the only clear solution to saving the kingdom would be killing its cursed queen.

Readers, what’s your verdict?

July 7, 2015

Book Launch day, Elisha Rex!

Today is the big day, the launch of book 3 in my Dark Apostle series of fantasy novels about medieval surgery. Please help me celebrate and spread the word!

Cover for Elisha Rex, book 3 in The Dark Apostle series

Once again, artist Cliff Nielsen has captured the spirit of the book–we find Elisha a changed man, in more ways than one–but here’s the cover copy to whet your interest:

“Blending magic and history, strong characters and gripping action, E. C. Ambrose brings a startlingly unique voice to our genre.”

—D. B. Jackson, author of Thieftaker

Elisha was once a lowly barber-surgeon, cutting hair and stitching wounds for poor peasants like himself in 14th century London. But that was before: before he was falsely accused of murder, and sent to die in an unjust war. Before he discovered his potential for a singularly deadly magic. Before he was forced to embrace his gifts and end the war…by using his newfound abilities to kill the tyrannical king.

So who is Elisha now? The beautiful witch Brigit, his former mentor, claims him for the magi, all those who have grasped the secrets of affinity and knowledge to manipulate mind and matter, and who are persecuted for it. Duke Randall, the man who first rose against the mad King Hugh, has accepted him as a comrade and ally in the perilous schemes of the nobility. Somehow, he has even become a friend to Thomas, both the rightful king and, something finer, a good man.

But there is another force at work in the world, a shadowy cabal beyond the might of kings and nobles, that sees its opportunity in the chaos of war and political turmoil—and sees its mirror in Elisha’s indivisible connection with Death. For these necromancers, Elisha is the ultimate prize, and the perfect tool.

When the necromancers’ secret plans begin to bear black fruit and King Thomas goes missing, England teeters on the brink of a hellish anarchy that could make the previous war look like a pleasant memory. Elisha may be the only man who can stop it. But if he steps forward and takes on the authority he is offered to save his nation, is he playing right into the mancers’ hands?

Why does it seem like his enemies are the ones most keen to call him Elisha Rex?

I have already drafted the fifth and final book in the series, but I promise, there’s plenty of excitement yet to come!

If you want to check out some of the behind-the-scenes stuff I researched for this volume, try my blog entries about: