E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 9

January 22, 2016

Editorial Greatness: In Memory of David G. Hartwell

This week, the science fiction and fantasy community was devastated by the loss of David G. Hartwell, long-time Tor editor, co-founder of the World Fantasy Convention, and an extraordinary man in every way. (especially his fashion-sense–seriously! His ties have their own website)

Unlike this year’s prior losses of David Bowie and Alan Rickman, this one, I take personally. I have known *of* David since I first aspired to sell a fantasy novel, more than twenty years ago. And when a friend more plugged in to the SF community told me that David read everything that crossed his desk personally, I found it hard to believe–surely, David Hartwell had more important things to do. And yet, I am not sure, from his perspective, if there were any more important job to an editor than discovering a new great writer, grooming their work for success, and helping it reach its audience. He considered discovering Gene Wolfe to be one of his greatest achievements.

I had only a couple of opportunities to talk with David directly about my work, most notably when he invited me to join him for breakfast at a World Fantasy Convention while he was considering my first novel. [David (via email) “Are you going to World Fantasy? We could have breakfast.” Me (thinking furiously about how to afford the trip): Yes!] During that meal, David told me things about my own book that I never thought anyone else would know or understand. In my case, I’m sure it helped that his background was in Medieval Studies. He ably demonstrated what makes a great editor.

Although I was not able to work with David on that project (and now mourn the lost dream that we would eventually work on books together), he showed by example many of the skills of the great editor. I have now had numerous editorial relationships both awful and wonderful. I often hear new writers or indie authors questioning the need for publishers at all–and I make the case for editors every time. Many indie authors know all about this, and hire their own editors. For the traditionally published author, the publisher will assign an editor to work with the novel–often the editor who selected the work for publication, though not always.

A great editor recognizes what is unique and striking about your work. They will identify the heart of the story and help you to craft the words to more carefully reveal that uniqueness. This requires careful reading and a global way of thinking about the work–the editor needs to see the forest, not just the trees.

A great editor also sees what makes the work similar to other works in the field. They can place this new novel in relation to those works for the benefit of the marketing and in-house designers, enabling them to generate book covers, cover copy and ancillary sales materials to reach the market segment most likely to fall in love with the book (as, hopefully, the editor did).

A great editor delivers feedback in a clear, organized, articulate and respectful way. The editor understands that their response (positive as well as negative) is important, but that the author is one who will develop the solutions to any concerns. The editor may have ideas about solutions, or aid in brainstorming, but trusts the author to create the one that is most suitable for the work. This may extend to aiding the author in developing a series concept or planning for additional projects.

A great editor helps the author to hone individual scenes, paragraphs and sentences to enhance their clarity and purpose. The editor questions things that aren’t working and may suggest cuts, but the purpose of the cuts is always to strengthen the work. The editor is open to negotiation about things the author thinks are critical about the story or style. The editor doesn’t try to change the work simply to “leave their mark” on it, or introduce stylistic elements that aren’t in keeping with the author’s voice.

A great editor communicates directly when working with either the author, or the author’s agent, if any, giving the information they need and guiding the work and the author through the process from a rough pile of words to a finished book on a shelf, virtual or physical.

A great editor is the book’s first fan, celebrating it and advocating for it both within the publishing house and outside of it.

David could be all of this and more. He was a voice for science fiction and fantasy, a thoughtful participant at conventions, a firm and illuminating moderator, a witty and enjoyable presence at parties and social affairs. He will be missed.

January 8, 2016

What I Hate About Writing Groups

Full disclosure here: I currently belong to four writers’ groups, as well as SFWA, my national genre organization. And I have recently dropped out of two others (and dropped out of another one last year, for similar reasons).

A good writers’ group offers the opportunity to meet with other writers, ideally those working toward a similar goal; to share information about writing whether that is submission opportunities, support, or promotion; and sometimes to get direct aid with a project of your own. This last is usually offered in the form of critiquing.

I think the critiquing of manuscripts is important, and, at some stages of the writer’s development, even critical. Working with a critique group not only gives you the chance to get feedback on your own work with an eye to improving it (or to improving your next work as you learn more), it also allows you to hone your eye as an analytical reader. I find I often learn more when I am examining someone else’s work and am forced to articulate my understanding of the work, finding information in the text to support my reactions. This kind of insight can be taken back to my own work, and is highly informative when I am writing or speaking about the craft of writing. It is often easier to see the flaws in someone else’s work than in your own, but you will likely find that flaw reduced in your next project because of that attention to learning.

Okay, E.C., but you drew me in here with a title about hating writing groups, now you’re going on about the benefits–what gives?

How the group approaches critiquing is vital to the success or frustration of a critiquing session. Some groups are strictly on-line. Works are exchanged via the internet, and returned with marginal notes as well as commentary on strengths and weaknesses. This makes it easy to digest the work as the critiquer reads it through and makes notes, and it makes it easy for the author to receive the commentary with a bit of personal distance. Nobody is saying to your face that they found your story confusing and your characters unsympathetic.

But when a group is managing in-person critiques, the approach is very different. Sometimes, the works are distributed and read in advance, with notes made just as described above. Then the participants offer a summary of their notes in the meeting, sometimes building on and responding to what the others say.

In the Milford Style critique, the participants give their feedback in round robin style, speaking one at a time. The author then has a couple of minutes to ask a question or seek clarification about issues that arose. Often, the author is encouraged to simply thank the readers for their time and trouble in preparing their comments. The author can then take away all that has been said, assimilate the information, and act on it (or not) as they choose. This is the way that most professional groups, and many long-standing workshops operate (Odyssey, Clarion, Milford itself).

But there is another way. . . the dark side, as it were. This approach is more social. Let’s call this the spontaneous style. The works are read at the session (on paper, if possible–usually easy to do with poetry, less so with longer works) aloud, usually by the author. Participants then respond to the work, sometimes from notes they have written down while listening, sometimes just off the top of their head. A well-organized spontaneous uses a round-robin style, and has some guidelines about how to give good, useful comments (ie, that comments are about the work, not about the author; that a comment should be constructive not destructive; that it should be specific). So the result can be similar to a Milford-style group, but modified for a number of participants which varies or in which not all the members could have been reached in advance to arrange a more formal system.

The problem comes when the critique session is not moderated in this way. Sometimes, the author is the de-facto moderator, responding directly as points are made, asking questions, guiding a conversation about the work. Often, the group is simply more of a free-for-all, where some people may begin by speaking about their reactions, then others start responding to that, rather than to the work. The worst-case scenario is when the participants, including the author, break out with interruptions or arguments about the work. Or rather, about an interpretation of the work, telling a respondent why they are wrong about their experience of the work.

And this is what I hate. When I am offering my feedback to an author, I do so in the spirit of helping the work to improve–to become more focused on the author’s intent and better at revealing its strengths. My reaction to the work is usually backed up by details of the text, as well as by years of experience with giving and receiving critiques, with writing my own dozens of books, articles, short stories, poems; and with teaching or leading writing groups. In short, not to brag or anything, but I’m not an idiot.

Yet nothing makes me feel more like an idiot than someone trying to convince me that my reaction to a literary work is wrong. When I have spent time thinking about the work and articulating a response to that work, I think I deserve to at least have my perspective heard. Whether the author chooses to act on it is up to them. When they won’t even listen to feedback, that’s a problem. If you have asked for honest feedback on a work, you must be prepared to receive it in the spirit in which it is offered: that the respondent genuinely hopes to help you improve the work. If you are not prepared for honest feedback, then ask not to receive comments, or simply wait to share your work until you are.

I think this happens in spontaneous groups because of the atmosphere they create. Up until the critique session, they are likely to be marked by cheerful social interaction, which may or may not revolve around writing. Often, they take place in a public setting like a coffee shop, and may involve a shared meal. All activities likely to build a sense of camaraderie. So when the critique begins, it’s easy to perceive it as part of the on-going conversation–or worse, as your friend criticizing your beloved art to your face, rather than as one colleague to another, helping to improve that art.

Some people seem to be satisfied with this kind of interaction, where the honest response of the audience is likely curtailed or deflected into a more general group atmosphere. But if, like me, you feel frustrated with the quality of feedback you receive in that situation, it may be time to leave. You might also choose to introduce a more formal and professional atmosphere by having guidelines for feedback (and for authors receiving that feedback), by selecting a moderator, by promoting a stronger distinction between a more general conversation and the critique session.

In any case, I hope that the writers among you are seeking and finding an appropriate and useful critique approach. And thank you for listening.

#SFWApro

January 1, 2016

Looking Ahead

2016 has arrived! I hope you are all looking forward to it as much as I am. Here are some of the happenings in the writing worlds of E. C. Ambrose. . .

The Dark Apostle. . .so far.

January finds me attending the Arisia convention in Boston, MA, which is always a good time–complete with a masquerade, gaming events, parties and lots of great panels.

I’ll also be revising The Dark Apostle, book 4, Elisha Mancer, with the aid of my editors’ notes to polish it up and make it the best book I can.

February features Boskone, a more literary convention, hosted by the New England Science Fiction Association, also in Boston. If you’re a writer of science fiction or fantasy (or would like to be) you’d get a lot out of this convention–it’s great for readers, too!

and I’ll be polishing the fifth and final Elisha volume to send over to my publisher for 2017 release–it’s hard to imagine the series wrapping up! I came up with the series ending a few years ago, and was appalled at myself, but also delighted. That feeling lead to one of my first blog entries five years ago. A wonderful, awful idea. . .

March is my own deadline for revising my first-ever international thriller novel, featuring a group of former Special Intelligence operatives, out to defend archaeological and cultural artifacts–they call themselves the Bone Guard. I had a blast writing this one, and I can’t wait to get it out to my readers.

April will find me teaching a workshop about book promotion at New Hampshire Writers’ Day, then in Utah, attending the Million Dollar Outlines workshop, with the amazing David Farland. I have some ideas for my next fantasy project. The workshop should serve as a retreat where I can focus on brainstorming and developing something truly epic. I can hardly wait.

But I have another book to write in the meantime. . .

In May, I get to return to the International Congress on Medieval Studies, in Kalamazoo, Michigan. This is the event where I get to pick the brains of thousands of experts on the fascinating details of the Middle Ages.

June. . . nope, got nothing. Yet. Maybe this is my month to finally summit Mount Washington? and revise that book I’ll be working on.

July 5th will see the launch of Elisha Mancer, and no doubt many other events besides. Quickly followed by Readercon, one of my favorite annual events–this one is all about the books. And a week of camping in the woods with teenagers to coach them on rock climbing. What’s not to love?

In August, alas, I will miss the World Science Fiction Convention, this year held in Kansas City, MO. I hope you all have a great time without me. There’s just so much a person can do in a year, after all. I will also be turning in my first science fiction novel, a collaborative book that I’m very excited about.

Which means, in September, my schedule will be clear to write that fantasy novel I plotted in April. Hopefully, I’ll be writing at 2000-3000 words a day, which seems to be a good pace for me. But that still means a couple of solid months of drafting.

October will find me at the World Fantasy Convention in Columbus, Ohio, to see the unveiling of the new World Fantasy Award statuette. What will it be? I’m very curious.

November. Maybe I’ll take my birthday off. . . nah, probably not. According to my two-year-plan spreadsheet, I’ll be brainstorming and pre-writing for a different kind of fantasy series. And, if my readers and my agent are excited about the first Bone Guard book, then it’ll be time to draft another one–don’t worry, I already have a half-dozen cool ideas for further volumes.

I can’t believe it’s December already! Must be time to revise the final volume. . .and then what? Who knows! But I will look forward to sharing it with you, dear friends and readers.

Have a happy New Year!

December 18, 2015

Above the Salt: a Medieval History of a Vital Spice

During the Middle Ages, spices were often a marker of wealth. Not everyone could afford them, and the idea of making a spice freely available on the table was purely extravagant–hence our term “above the salt,” meaning those people so privileged that they could sit close to the lord and help themselves from the saltcellar positioned for the use of the nobility.

A carving of the Last Supper in a salt mine chapel, Judas is often identified by an overturned saltcellar on the table in front of him.

Nowadays, salt is so ubiquitous that people can suffer from too much of it. We take it for granted, and are more likely to be trying to restrict its presence than to celebrate it. Sea salt is all the rage, and specialty stores sell different varieties of salt, with different origins and mineral contents. The pink Himalayan variety is especially prized (and makes cool lamps). But during the Middle Ages, white salt, carefully purified, was the prize (just like white sugar and white bread–which suggests another blog entirely. . .)

Salt, then as now, was especially vital, not as a spice, but as a preservative. Salt pork, hams, bacon, great barrels of salted fish were a key source of food, especially for armies on the march. Salted foods could last a long time, enabling sea voyages and long marches (or the withstanding of a siege, depending on which side had the goods). In the dreary north, where they rarely got enough sunlight to refine salt from sea water by solar evaporation, cakes of salt were important trade items.

England was lucky. While the British weather is notoriously the opposite of sunny, England has deposits of mineral salt, notably in Cheshire, where salt could be mined, usually by leaching it out with great quantities of water, resulting in brine which was then let into shallow pans to evaporate into salt. Roman-era salt pans and kilns for drying the brine have been found in the area. In the early modern period and later, they removed so much salt from the ground in this fashion that areas of land simply collapsed as the substrate dissolved out from under.

In the Tyrolean region of the Holy Roman Empire, salt was a highly valuable commodity, sold across Europe to preserve food for various armies. This history is acknowledged in names like Salzburg (“salt mountain”). Not only was rock salt mined extensively in the region, from at least the 1200’s, salt baths were also touted for health reasons, and people traveled to spas to bathe in the hopes of curing everything from skin ailments to joint aches (perhaps because the added buoyancy allows the patient to relieve the strain). When you see the word “Bad” in the name of a Germanic town, it refers to the baths. Several of the mines even incorporate churches for the benefit of the miners who labored there.

When I was researching the history of salt, I found several references to the use of animal blood as an additive to a brine to separate impurities. It is my theory that this is actually the origin of the term “Kosher salt,” which would refer to salt that had been made without the use of blood.

The preservative aspect of salt had another interesting side effect: salt mummies. Miners who died in the mines, even in ancient times, could be very well preserved, along with their clothing and personal effects–until they were found by later miners or explorers.

a salt-preserved mummy found in Iran in 1993

This is, of course, what makes for the research rabbit hole. You just want to know a little bit more about medieval saltworks, and you end up stumbling over the bodies. Let’s move back above the salt, shall we?

December 11, 2015

Jubilee! The Theoretical Papal Homecoming of 1350

Pope Francis recently declared a Jubilee Year, which officially began on Tuesday, with the timely theme of Mercy. In doing so, he follows a tradition nearly a millennium old of encouraging pilgrimage to Rome. For the Catholic who is able to make the journey, and make the official circuit of worship there, a heavenly reward awaits: remission of sins. Nice!

The tradition goes back to the Judaic roots of Christianity, with the celebration when all of the twelve tribes could return to Israel. Let’s just say that one hasn’t been celebrated in the modern era. The first official Catholic Jubilee year was held by Pope Boniface VIII in 1300, with the intention that they should be held every hundred years. In the era of my research, the poet Petrarch, eager to convince the papal court to return to Rome from Avignon (a situation which he termed the Babylonian Captivity), talked Clement VI into declaring 1350 to be a Jubilee year–in the hopes that the city would pull itself together, and the pope would come home to Italy to stay.

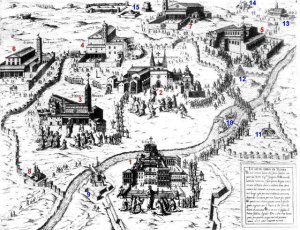

A map of the seven holy churches pilgrims must visit in Rome in order to earn an indulgence during a Jubilee year.

In the run-up to 1350, let’s just say, Rome was a bit of a mess. It was the battleground of two warring families, the Colonna and the Orsini, together with their allies, and was briefly run by the fascinating madman, Cola di Rienzo. Cola was a good friend of Petrarch’s, and they worked on the Jubilee plan together. In 1350, in order to earn the indulgence (the remission of sin), the pilgrim had to visit the seven great churches of Rome, some of which lay outside the walls (San Lorenzo and San Paolo fuori le Mura, which means “outside the wall”), and were thus in more dangerous territory. Others, like San Giovanni and Santa Maria Maggiore, were claimed by the Colonna, while Saint Peter’s belonged to the Orsini.

The plans of populists and poets do not always run smoothly. Aside from overcoming the reluctance of the papal court to return to the chaos of Rome, the plan suffered another set-back in the winter of 1348, when an earthquake centered in Friuli (in the Alps) damaged several of the churches and shattered an already broken city. By then, Cola had been expelled–with the backing of the pope, his one-time supporter. And, oh, right, there was the plague.

The Great Pestilence, as it was then called, swept through Europe starting late in 1347 and continuing through the following year. It ravaged the countryside and the cities, killing peasant and lord alike, as was then observed. Some people received this as the sign of God’s displeasure, and suggested that atonement was even more necessary, like the Swedish mystic, Saint Bridgit, who traveled to Rome for the Holy Year, and urged others to do likewise, and remained there for the rest of her life, doing good works. (as an aside to those who have read my books, was I tempted by this coincidence of name, absolutely. But my Brigit has her own work to do, and it may not be “good”. . .)

Alas, Pope Clement VI did not return to Rome, in spite of the Jubilee. His successor, Urban V did go there briefly, but did not stay. The permanent return fell to Pope Gregory XI, who is claimed as the nephew of Clement VI, but was often rumored to be his son. Gregory XI had a long history with Rome, where he was, during the time of the Great Pestilence, a priest named Pierre Roger, and the archpriest of San Giovanni.

This Jubilee year takes place without plague, at least, and Rome itself is a bastion of stability compared with so much of the world. If Pope Francis and this ancient tradition can encourage some people to focus on mercy, that sounds like a great plan to me. I can only wish that some other leaders would do the same.

November 20, 2015

The Beastly Tower: a Royal Menagerie

One of the most fascinating features of the Tower of London which has, alas, been lost to time is the Tower Menagerie, which makes an appearance in Elisha Rex. How could I resist a setting like that?

Tower of London: the green area you see was originally the moat, and the current tourist entrance occupies the gate once surrounded by the menagerie.

The menagerie began (so far as we know) during the reign of the singularly unpopular King John around 1210, when we find references to the “keepers of the lion” in the royal account books. The menagerie, a collection of exotic animals, might have begun with animals brought as gifts to the monarchs, and the early records show the residents were often beasts associated with royal arms, like the lion, or the leopards of Henry III. This collection displayed the monarchs’ great reach and power, commanding exotic creatures from many corners of the globe. The Tower’s website has a timeline about the menagerie as well, though it does not include the same information in the Official Illustrated History of the Tower of London.

One notable resident was a polar bear, given as a diplomatic gift by the king of Norway in 1251, who was given a leash long enough to allow him to fish in the Thames River. Another exotic likely given to show the wealth and influence of the giver rather than the receiver was an elephant from Louis IX of France. This gift required a new building to be constructed, but according to most sources, the elephant did not live long, and was promptly buried in the structure meant to house it. An elephant buried on the Tower grounds? Now there’s a thought.

At times lion or bear fights were popular entertainments at the Tower–which makes one very curious about the Tower link above, which guarantees admission to a Tower Beasts “interactive” exhibit. Those of you who have read Elisha Rex will know that Elisha receives a personal interactive tour of the menagerie–including some interactions perhaps better avoided.

In fact, the animals of the menagerie were sent off to the zoo in 1832 after a series of attacks on keepers and visitors, ending this curious by-way in Tower history.

an engraving of the Tower of London menagerie, showing the arched recesses where animals were kept.

November 13, 2015

Warriors and Soldiers and Fantasy Novels

I had a great time this weekend at the World Fantasy Convention, this year held in Saratoga Springs, NY. One of the highlights came right at the end with a very thought-provoking panel about Weapons in Epic Fantasy. The panelists included Charles Gannon, Summer Hanford, and Ian Cameron Esselmont. I believe it was Cameron who made an interesting point I hadn’t considered in relation to my current work.

We were talking about the relationship between the hero of a fantasy work and his weapon. In an earlier age, and in much current fantasy, this relationship is personal–between the hero and his sword. These swords are often named, and sometimes have personalities and desires of their own, as in Travis Heerman’s Ronin series. The roots of this heroic bond go back to the roots of the epic, when it referred to a lengthy saga detailing the origin of a culture and revealing that culture from top to bottom. These original epics have what might be termed a warrior ethos: they focus on the deeds of the mighty individual as he confronts his enemies, often in a battle for personal honor as well as national pride.

Cameron brought up the difference between this warrior, and the soldier, a member of a trained and organized military unit. The soldier likely has personal honor and national pride among his values, but on the battlefield, he works for the objective of his unit or commander, subsuming his individual goals for those of the larger force. The effective soldier cooperates with his team and focuses on that larger goal, while the effective warrior stands apart from others. He may lead them–but then again, he may just retire to his tent and sulk for a while like Achilles during the Trojan War if he feels insulted. His (in the original epics, the hero is almost always male) personal values take precedence. This behavior is held up as an exemplar of the hero.

The soldier, on the other hand, may not be recognized for his individual feats, but rather for his successful participation in a team effort. Many years ago, I was wearing a pin with a reference to heroes, and an older writer, a journalist, commented, “I don’t like that word, heroes.” I have returned to his statement periodically, considering what he might have meant by it. This man was a decorated veteran of the second World War, a soldier, who did not approve of the word “heroes.”

I think now, he may have been referring to exactly this distinction between warrior and soldier. In modern warfare, the term “hero” is often applied to someone who stands apart, as did the warriors of old. The “hero” may have earned this term through their own honorable death, perhaps in service to that team effort. But you will often hear people warned, “Don’t be a hero.” Meaning, I think, don’t make yourself a target or a casualty by stepping outside the team.

There will always be soldiers who go above and beyond the call of duty and distinguish themselves, not for the behavior of the solitary warrior who places his pride above the needs of the unit, but because they take upon themselves actions that are daring and dangerous–and committed to furthering the team, and not themselves.

In this week of Veteran’s Day, I did not expect to find such fodder for consideration in fantasy–and yet, there it was. Heroes, warriors, soldiers. I hope, when I write, to honor their spirit if only from a respectful distance.

November 6, 2015

Guest Author Juliet McKenna, epic fantasy and more!

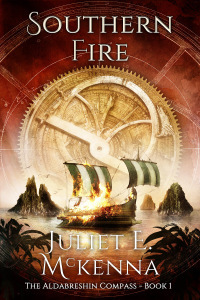

What do Syria, Wiccan practice and jiu-jitsu suffragettes have in common? They all spark the imagination of my guest author, Juliet E. McKenna, whose latest epic fantasy novel, Southern Fire, will be available soon!

the gorgeous cover for Southern Fire, first in a new series by Juliet L. McKenna

1. What was the inception of this project? What were your first steps in building that idea into a viable story?

My first epic fantasy series explored ways in which ordinary people could get caught up in the affairs of wizards and princes, how they might react and how they could still influence outcomes without the advantages of magical or political power. Looking to write something new, I found myself turning that idea around. What about a story where someone with significant magical or political power gets caught up in a situation where those advantages can’t actually solve the problem? Since as we all know, with great power comes great responsibility, that’s going to be a major crisis. Everyone lower down the pecking order will be looking at the person at the top, expecting them to put things right.

How and where could that happen in the world I’d already created? It was immediately obvious. I’d already established the Aldabreshin Archipelago was a swathe of island domains ruled by warlords with absolute, unquestioned power, all with an implacable hatred of magic. So if magic turned up causing strife, they’d be in real trouble. Especially if that wasn’t civilised, wizardly magic which could be negotiated with but something else entirely… By that stage, my imagination was off and running!

2. What kind of research and/or world-building did you do before beginning?

Since the Aldabreshin Archipelago is in this secondary world’s tropical latitudes, it was already established that, logically, the inhabitants were people of colour. This was an obvious prompt for me to move away from the Northern and Central European cultures and myths I’d drawn on so far in my work. So I read a stack of African, Indian, Near- and Middle-Eastern histories, some general and others focusing on specific themes and periods, always making sure to read as much as possible written by experts whose history and culture these actually are. This gave me a wealth of material to draw on; for devising customs, attitudes, expectations, clothing, furnishings, you name it. All of this is so vital for creating a vivid sense of place and culture. And wide reading is essential to avoid falling into that awful trap of appropriating one particular culture wholesale and hoping no one will notice just because the writer has changed the hairdos and hemlines.

Since Aldabreshin reliance on divination, omens and portents had already been sketched in, when characters from the Tales of Einarinn visited these islands, I had to develop that belief system far more fully, so I read up on such beliefs from Ancient Babylonian astrology all the way up to modern Wiccan practise. Studying symbology in particular was absolutely fascinating.

Then there was exploring historical examples of the limitations of absolute power and failures of the hereditary principle. What happens when the heir to a throne is simply not up to the task? What happens when an absolute ruler decides they can behave however badly they like without fear of the consequences? How have different feudal, authoritarian cultures dealt with the perennial problem of surplus sons, once they’ve got the heir and the spare?

3. How does the real world (historical or contemporary) affect your speculative fiction?

Historical research, including social as well as political history, gives me the solid foundation that’s essential for building a fantasy world which readers can really believe in; from the everyday detail drawn from real events to the actions and reactions of the people who live there, tested against the real world behaviour of family, friends and strangers around me. Because if readers can believe in the world, they can believe in the magic and dragons.

My reading also turns up unforeseen incidents, people and pre-industrial technologies which I would never have imagined unprompted but which turn out to be just what I need to spark a new idea to significantly improve a story. It also gives me solid references for those moments when someone protests something I’ve written is implausible ‘because history wasn’t like that’. Discussing how and why the history which they were taught wasn’t the whole story by any means is always illuminating.

Incidentally, my reading for fictional-research purposes frequently improves my own understanding of the contemporary world around me and in the news. World-building for The Aldabreshin Compass series taught me an awful lot about the history, cultures and religions of what’s now Turkey, Syria, Iran, Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula. That gives me invaluable perspective on current events in that part of the world.

4. If you could choose a few descriptors that would go in a blurb on the front cover of your book, what would they be?

Tricky; I’ve never worked in advertising and besides, British women of my generation are always told firmly not to put ourselves forward… How about –

“Intricate, inventive, enthralling.”

“Worlds away from Tolkien. That was epic fantasy then. This is now.”

“How far must a man go to be the hero everyone expects? What will he lose on that journey?”

5. Where should readers go to find out more about your work?

My website’s the obvious place to start. There are sections introducing each of my series so far, along with more detail on each individual book and sample chapters for reading, as well as maps and background material for the curious. Along with other oddments of quite different fiction and the blog where I discuss things that amuse or interest me, so that should help people decide if we’re generally on the same wavelength.

6. Care to share a link (aside from your own work) to something amazing you think everyone should see or know about?

The history that isn’t taught is so often the history of women and minorities. I love the story of Edith Garrud, who taught ju-jitsu to a crack bodyguard unit of UK suffragettes, to run interference between the police and the Pankhursts (among others). This wikipedia entry is merely a starting point for a tale that upends so many incorrect assumptions about days gone by. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edith_Margaret_Garrud

and check out the BBC’s article as well!

Edith Garrud in action!

head shot of author Juliet E. McKenna

October 29, 2015

Guest Author, Gail Z. Martin: Days of the Dead tour!

The fantastic Gail Z. Martin is stopping in today, as part of her Days of the Dead tour, to share her thoughts on Addictive Research, and celebrate her latest releases, Vendetta, and Iron and Blood. I love this article–she sounds a lot like me. And, she’s offering some great Trick-0r-Treat items, just for readers–see the links at the end!

Just one more. I’ll quit after one more, I swear.

That’s your inner research junkie talking. One more link, one more web page, one more book or chapter in the research book, one more biography, one more footnote. Hyperlinks let researchers mainline information, jumping from site to site, following Alice’s White Rabbit farther and farther down the hole.

To everyone who hated writing research papers in school, I’ve got one thing to say—you didn’t know what you were missing. Get good at research, document your sources, find good primary sources, and you can challenge authority figures and stand your ground. You can overturn accepted thinking and chisel away at deceptive reasoning. Armed with definitive experts, unimpeachable documentation, excellent analytical skills and persuasive writing ability, you become Conan, the librarian. Demagogues tremble and empires crumble before the blinding light of your research.

Or, you just get your facts right and escape social humiliation.

Every author I know loves research. It’s our guilty pleasure, and if we’re not careful, our worst time vampire. Get a bit of writer’s block? Do some research. Odds are, you’d happen upon a few cool facts that blow away your mental obstacle and present a path to reach your goal. On the other hand, if you feel like procrastinating you can do “research” all afternoon, following your curiosity like a hound on the scent of a fox (or a Golden Retriever on the scent of a squirrel), and come away with knowledge that will make you killer at Trivial Pursuit but doesn’t get you any farther on your writing project.

Some aspiring authors get lost in their research and forget to ever write the book. This is particularly dangerous if you’re a perfectionist. No matter how much you research, you’ll never know everything about your subject. There’s always the chance that the next tidbit of information you’d uncover might be even more amazing than the last one. You become the intellectual equivalent of a gambler addicted to the slot machines, pulling that lever and hoping for a jackpot. Next time. Next time. You feel lucky.

Sometimes, writers use research as an excuse not to write because something about the writing is causing anxiety. Maybe you’re afraid that this book won’t be as good as the last one, or as good as the hype claims it will be. Perhaps you don’t want to reach the end of a series, or kill off a favorite character, or write a difficult scene. Research becomes a legitimate delaying tactic, a way no one can say you aren’t working, but you’re not really working. You’re hiding in the stacks, hoping no one notices.

The day-to-day reality lies somewhere in between research as a superpower and research as an addiction. Yes, research can be like the dynamite that blows away a rockslide and clears the road, helping you see a path to reach your story objectives. And yes, it can be a monkey on your back, whispering that ‘one more couldn’t hurt’.

What saves me, and I suspect most writers, is that the call of the story in our minds is even louder than the seductive whisper of research. If I’m fully invested in writing a story, I want to see how it ends. (Sounds silly, but there are a lot of things that come up spur-of-the-moment that surprise the writer, and we live for those moments.) Ultimately, that’s my beacon out of the Valley of the Lotus Eaters, the field of poppies. When temptation becomes overwhelming, I shut off my wi-fi and remind myself that I’ve got a story to write.

My Days of the Dead blog tour runs through October 31 with never-before-seen cover art, brand new excerpts from upcoming books and recent short stories, interviews, guest blog posts, giveaways and more! Plus, I’ll be including extra excerpt links for my stories and for books by author friends of mine. You’ve got to visit the participating sites to get the goodies, just like Trick or Treat! Details here: http://www.ascendantkingdoms.com/2015/10/22/days-of-the-dead-blog-tour-tricks-treats-and-scary-good-stuff/

Book swag is the new Trick-or-Treat! Grab your envelope of book swag awesomeness from me & 10 authors http://on.fb.me/1h4rIIe before 11/1!

Trick or Treat! Excerpt from my new urban fantasy novel Vendetta set in my Deadly Curiosities world here http://bit.ly/1ZXCPVS Launches Dec. 29

More Treats! Enter to win a copy of Deadly Curiosities! https://www.goodreads.com/giveaway/show/160181-deadly-curiosities

Treats! Enter to win a copy of Iron & Blood! https://www.goodreads.com/giveaway/show/160182-iron-blood

Gail Z. Martin, Dreamspinner Communications

About the Author

Gail Z. Martin is the author of the upcoming novel Vendetta: A Deadly Curiosities Novel in her urban fantasy series set in Charleston, SC (Dec. 2015, Solaris Books) as well as the epic fantasy novel Shadow and Flame (March, 2016 Orbit Books) which is the fourth and final book in the Ascendant Kingdoms Saga. Shadowed Path, an anthology of Jonmarc Vahanian short stories set in the world of The Summoner, debuts from Solaris books in June, 2016.

Other books include The Jake Desmet Adventures a new Steampunk series (Solaris Books) co-authored with Larry N. Martin as well as Ice Forged, Reign of Ash and War of Shadows in The Ascendant Kingdoms Saga, The Chronicles of The Necromancer series (The Summoner, The Blood King, Dark Haven, Dark Lady’s Chosen) from Solaris Books and The Fallen Kings Cycle (The Sworn, The Dread) from Orbit Books and the urban fantasy novel Deadly Curiosities from Solaris Books.

Gail writes four series of ebook short stories: The Jonmarc Vahanian Adventures, The Deadly Curiosities Adventures, The King’s Convicts series, and together with Larry N. Martin, The Storm and Fury Adventures. Her work has appeared in over 20 US/UK anthologies. Newest anthologies include: The Big Bad 2, Athena’s Daughters, Realms of Imagination, Heroes, With Great Power, and (co-authored with Larry N. Martin) Space, Contact Light, The Weird Wild West, The Side of Good/The Side of Evil, Alien Artifacts, Clockwork Universe: Steampunk vs. Aliens.

October 27, 2015

Drafting the Novel: How long did that take you to write?

On Friday, I finished the first draft of my first international thriller novel. It’s always an exciting moment to finish a project, especially one that you’ve been planning for a long time. One of the things that readers often ask about a book is, how long did that take you to write?

top view of notebooks for Drakemaster (epic fantasy) and thriller novel, about half as long. Both printed double-sided.

It’s a bit of a tricky question to answer. Do you mean, when did I first conceive of the notion, how long did it take to develop the concept into a plot and characters, or how long did the literal first draft take from beginning to end? And even that can be a complicated statistic. For instance, the thriller has been in the back of my mind for years. I did a lot of research and story development before I ever made a new file on the computer and wrote the first sentence.

But for those looking for statistics, here are some. I started the draft on June 3, by writing 2304 words. I finished on October 23 (that’s 141 days). This feels like a long time to me, but I also was leading camps and taking care of many other things over the summer–so I wasn’t actually writing every day (it’s nice when I can do that, but it doesn’t always work out, especially during camp season). I actually wrote on 51 of those days, with a low day of a measly 92 words, and a high of 4633 (on the last day) for an average of 2107.82 words per day. I aim for 2000 words a day, so that’s pretty good. I have a spreadsheet where I keep track of each day that I write and my word count for the day, plus the total for the book.

The draft of book 5 in the Dark Apostle series, which I wrote in the spring, took 36 days, between March 27, and June 13, with an average of 2519 words per day. That’s a pretty big difference–why so? In part, I know Elisha very well. I don’t have to do a lot of thinking or outside writing to figure out who he is, where he is, and what might happen next. With the thriller, I had an all-new cast, with three point of view characters to choose from. I had to ask who would narrate the next scene and when and where it would take place.

Interestingly, those two novels overlapped by a few days–I had felt inspired about the first scene of the thriller, so I went ahead and wrote it, while I was considering the climax of the final volume of the Dark Apostle. Climaxes always take a little time to work out. Sometimes, I take a day or two off, ideally doing something active (hiking is good!) and play with the various possibilities in my head until I find the A-HA! moment when I can see a really great ending. Then the last bit of writing, as it did with the thriller, comes in a rush–and I hate to be distracted by anything.

The first Dark Apostle novel, Elisha Barber, took 35 days, writing every day, for the first draft. I wrote it as a chapter-a-day challenge, my answer to NANOWRIMO, and found that that pace felt very comfortable, hence my 2K a day word goal. Drakemaster, my Chinese historical epic, was 47 days of writing, with an average of 3171 words per day–which is pretty high. I think I was able to do that mainly because of the amount of pre-writing I did: brainstorming about plot and characters, developing a storyline for each character separately, making it easy to develop their individual scenes.

I find that, once I start drafting, writing every day makes it much easier to maintain my energy and momentum–and just keep writing. So the question is, what shall I write next? Hmmm. . .

#SFWA