E.C. Ambrose's Blog, page 6

November 5, 2016

God’s Clockmakers: factors in the early development of time-keeping technology

A few weeks ago, when I wrote about the medieval engineers of Islam, I promised a more general view of the role of religion in the development of clocks. The association goes way back. If you think about it, this makes sense. For millennia, people didn’t really need to know anything specific about time. Dawn= time to get up, Dusk = time to go to bed (or time to hunt certain kinds of animals, and to be hunted by others). Clues about the change of the seasons told you when to move hunting grounds and which direction to go, or when to plant crops and what to plant.

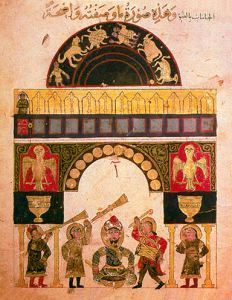

al-Jazari’s castle clock at Bagdad

It’s only when people begin to organize more conscious societies and these societies began to create rituals that a more precise division of time became necessary. I started out with the intent of talking about religion, but really, the development of clocks was driven at least as much by bureaucracy, and by people who wanted to get the most for their time–whether that was lawyers or prostitutes.

Enter the Water Thief or Clepsydra. Water clocks have been discovered in many different parts of the world, including Egypt, Babylon, China and India. But I love the term “Clepsydra,” the Greek word for these simple devices. Their development in Babylon relates to a judicious arrangement of water rights by local municipalities, and in Iran around 500 B.C. they were used to monitor holy days. Basically, the water clock keeps time by water flowing into or out of the device at a regular rate, as indicated by markings on the container. It needs to be re-filled from time to time, but, unlike the sundial, it works regardless of the weather or its location. So if you were an early Christian monk, you could have a water clock in your chamber to mark the hours of prayer–and this remained the most accurate method of time-keeping until the 17th century.

The water clock became highly elaborate during the Greco-Roman period, with elaborate gearing and water-driven figures that appeared to come alive to mark the hours. The Tower of the Winds in Athens is the remnant of a large public clepsydra. The Greeks used their clocks to time speakers in court cases, and the visits of patrons at brothels to ensure that everyone was treated fairly.

a model of Su Song’s astronomical clock in the collection of London’s Museum of Science

My favorite exploration of the water clock, however, emerged in China around 1080 AD, with Su Song’s astronomical clock. This clock used water to turn all of its incredibly detailed machinery, but all to serve the purpose of tracking the birth of imperial children in order to produce the most accurate astrological charts to ensure good governance by these representatives of the divine upon earth. At the top of the tower are the astronomical instruments, to the right in this image are the mechanisms that drive the clock, linked to the instruments above to synchronize their turning, and to the left, you can see the large barrel-shape of the display.

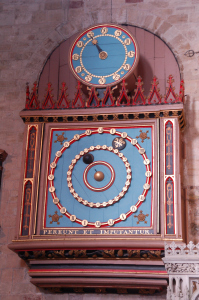

At medieval churches throughout Europe, sundials featured as a way to mark the hours and bells to summon people to pray. The sundials gave way to mechanical clocks with their own ways to chime the hours, often with cycles of the moon or other astronomical phenomena. But they still needed to solve the problem of the escapement: the mechanism that transfers the energy of the moving force (water or a spring) to the dial in a regular and controlled fashion. Enter Richard of Wallingford, a thirteenth century abbot memorialized as God’s Clockmaker for his work in the development of the mechanical escapement, employed in the tower clock at St. Alban’s. After this, many other varieties of escapement were tried, with the goal of making the clocks ever smaller and more accurate.

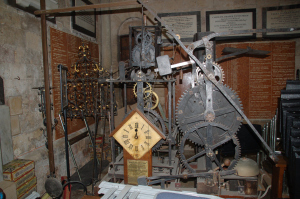

Sadly, as the clocks became more elaborate, that also meant specialized labor was needed to maintain them, and many of those magnificent early clocks, incluing Su Song’s and al-Jazari’s, were lost to war or dis-repair. I delighted in finding medieval clocks still in place in many English churches, some of them still keeping the time. Here are a few of them for your enjoyment.

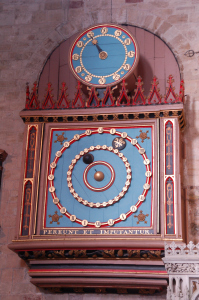

A lovely astronomical clock in Exeter, UK

the bell-striking “Jacks” at Wells Cathedral clock dating to the late 14th century

a retired mechanism at St. Mary Ottery

astronomical clock at St. Mary Ottery

October 21, 2016

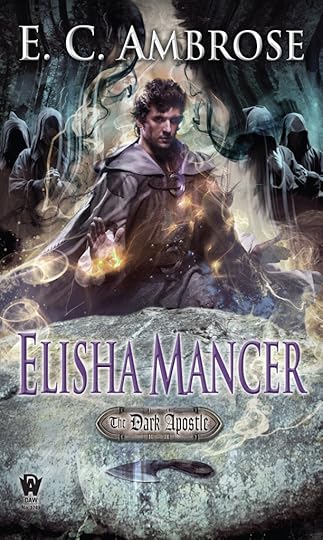

Elisha Mancer cover reveal!

Yes, it’s finally here–the day I can share the amazing new cover art, by Cliff Nielsen, for Elisha Mancer, book 4 in my Dark Apostle series. This volume takes Elisha to the Continent to track down his enemies before they can undermine the Holy Roman Empire, and the Holy Church itself!

Elisha Mancer cover art, by Cliff Nielsen

Autumn, 1347. . .terror stalks Europe as necromancers conspire to topple kings, corrupt an empire and undermine the Holy Church itself.

Armed with a healer’s skill and a witch’s art, Elisha hurries to the Continent to warn the Holy Roman Emperor and discover how to stop the mancers’ plans. But his enemies lurk in markets and churches, abducting innocents to torture and kill, using these slayings to open a passage through the Valley of the Shadow of Death. If he fights for a single life, Elisha may well become the next victim. With his affinity for both life and death, Elisha is by turns claimed for a savior, or for one of the very enemy he faces.

When he uncovers a scheme to lure thousands of pilgrims to Rome, Elisha’s hunt takes him from the opulent empire to the ruined Eternal City: abandoned by the Pope, shattered by baronial squabbles, and now ruled by a madman. At least, on the surface above. In the catacombs lurks an entirely different sort of leader, a master of death more powerful than Elisha himself.

A one-eyed priest, a seductive traitor, a stern rabbi, a merchant of bones—how can he tell friend from foe when he no longer recognizes himself? Every blow Elisha strikes draws him toward the wrong side of the battle. When the enemy retaliates in blood, he fights to keep his humanity lest he be consumed by the spreading darkness and become. . .Elisha Mancer

Elisha Mancer launches on February 7, 2017, and will be available wherever books are sold. You can pre-order now, on Amazon, Barnes and Noble, or through your local independent book store!

#SFWApro

October 5, 2016

What’s Your Sign? Ophiuchus!

It’s not the first time I’ve written about the conjunction between astronomy and astrology–for a long time, they were considered to be essentially the same thing. The only reason to study the stars was to understand how they governed those born beneath them. But I wasn’t expecting the current kerfuffle about NASA’s new zodiac.

A lovely astronomical clock in Exeter, UK

The plane of the zodiac, or the ecliptic, is the space through which the earth moves on its orbit, such that different signs are ascendant (that is, rising in the east when someone is born) at a certain predictable time of year, and those signs, since Babylonian days have been considered significant. Greco-Roman culture adopted this concept by the 4th century BC, giving the astrological signs their familiar names, which you can find in some newspaper columns to this very day.

However, NASA now tells us, the axis of the earth has shifted. Not only does it mean you were probably not born under the sign you’ve always believed, but there’s a whole new sign: Ophiucus, the serpent-bearer. Okay, when I heard about that, I kinda wished I were born between Nov. 29 and Dec. 17 and could proudly claim my serpents. Alas, not so. I’m curious to see if astrologers are going to pick up the new sign and run with it, giving advice to the serpent-bearers among us (like: grasp them right behind the head. If you get bitten, don’t suck out the venom. . .)

According to NASA, however, the Babylonians knew about Ophiucus, and decided to expel him as a 13th sign because it was hard enough to divide the sky (and the humans beneath it) into 12 slices, never mind 13. So it turns out that this “new” zodiac, is actually just an older one that had been discarded as messy. As above, so below. Life is messy, why shouldn’t the zodiac be? After all, this is organic life imposing our vision on stars that have been around for billions of years, oblivious to our very existence. Of course, we want to reach out to claim them and tame them, turning them into reflections of our own stories.

Now, Ophiucus is rising once again! But one suspects the Babylonians were not the only ones already in on the secret. What about the snake-handling cults of Appalachia, who take literally Mark, chapter 16, Verses 17-18, saying that the believers shall “take up serpents”? It must also be the sign of the Slytherins, which suggests to me that dark days are coming. Fortunately, wiki-how gives clear, concise instructions on how to handle the snakes. Now if they could just give us some advice about handling politicians. . .

September 30, 2016

A Brief History of Jews in China

Continuing my inadvertent series about surprising cultural connections (and my ruminations on the fact that history so often repeats itself), I recently came across this article in the New York Times about the clampdown on public practice of Judaism in Kaifeng, China. The article is interesting, but rather vague about the history of Judaism in the area. That happens to be one of the subjects I’ve researched in the last year for an epic historical fantasy novel set in Song Dynasty China, during the Mongol invasions.

A re-constructed Song Dynasty building in Kaifeng, China.

When I set out to write a book set in China, I was somewhat at a loss. China has a vast land area and deep historical and cultural richness. Where would I even begin? So, as I often do, I plunged into the research to see what might spark some ideas that resonated with the technology I wanted to write about.

Kaifeng almost immediately leapt out as a setting. Situated on the Yellow River, Kaifeng was the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty, until the incursions from the horsemen of the steppes forced the empire to move south before the area was finally overwhelmed. As the seat of empire, Kaifeng was home to Su Sung’s astronomical clock (the device which started me down this road) which was completed in 1090. It was sacked by Jurchen raiders in 1126, then beseiged by the Mongols in 1232-3, though it later rebelled against Mongol rule. So there’s all kinds of fascinating history to work with.

But the Jews were already there. Before all of that. Some scholars believe the Jews first settled in Kaifeng during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), merchants from Persia. According to tradition, they were invited to settle by the emperor, who wished to encourage scholarship in all forms, and had heard that the Jews were learned people. During a later crackdown on foreign influences and religions, they were expelled, along with the Buddhists (hey–let’s crack down on foreign influence! A thousand plus years later, they’re doing it again.) Only to return again with trade along the Silk Roads.

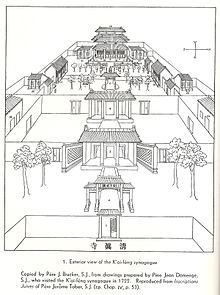

A sketch of the Kaifeng Synagogue

At any rate, there was a synagogue in Kaifeng from 1163. The Mongol empire was notoriously accepting of a variety of religions and cultures, with minority advisors on staff, including Jews. During the Yuan (Mongol) dynasty, many laws that favored Han Chinese citizens were lifted, to the benefit of Jews and Muslims, among others. Some new restrictions arrived, naturally, but the Jews seem to have done well for a time under Mongol rule. In 1368, when the Han returned to power, overthrowing the Mongols, the Han-centric laws returned in force, but the Jews were granted additional land and continued to prosper.

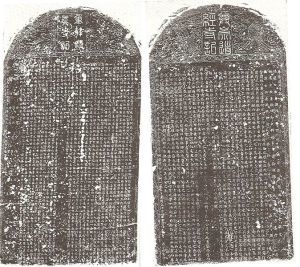

19th century rubbings of the Kaifeng stele

Two famous stele (tall stone monuments) erected near the site of the synagogue in 1489 and 1512 refer to the Jews’ loyalty to China, and the emperor’s decree that they should be free to practice their religion. The Jews also expressed their appreciation for permission to re-build the synagogue which had been destroyed during earlier invasions. In 1642 to quash rebellion, the Ming army broke the dam on the Yellow River, flooding the city, and killing many more people than they had intended, dispersing the Jewish community for a long time. Stories from the era tell of a brave man who dove into the flood to rescue the Torah scrolls from the drowned synagogue.

The Jewish community became increasingly absorbed into the general population, intermarrying and letting many practices fall away, until a resurgence in the late 1900’s. Even so, there is a continuous tradition of Judaism in the area, with many families proudly maintaining their Jewish heritage to the present day.

For me, as a writer, the Jewish presence in Kaifeng cinched its nomination as the primary location for my novel (working title: Drakemaster). I wanted to look at medieval multi-culturalism, and that, plus the layering of invasion, siege and rebellion made this a fascinating time and place to research. The more I study history, the more aware I become of our monolithic expectations of other times and places. We think of the past as provincial, peopled by isolated groups, who might have traded goods, but little else. The revelation of a Jewish population in China opened my eyes. As is so often the case with minority groups, they were already there, and they deserve to be recognized.

September 16, 2016

The Medieval Engineers of Islam

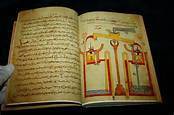

Many of my historical projects have delved into the technology of the Middle Ages, and it’s a topic I enjoy researching. I am always discovering cool things–sometimes things I’m not, alas, in a position to use. One fantastic example is the work of Ismail al-Jazari, who, in 1206 produced the absolutely stunning Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Devices.

A folio from the Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Devices.

This work details, in words and images, a hundred designs for inventions, many of them beautifully frivolous automata, like a water-propelled boat that sails across a decorative pool while the musicians on board perform on their musical instruments. A series of tubes and shafts allow water and air pressure to alter, forcing the air out of the tiny flutes to make them whistle.

A boatload of mechanical musicians.

Others were more serious. Religious observance has long been a driving factor in the invention and improvement of time-keeping devices (which I should use as a blog topic all by itself–idea noted), and Islam has been no exception. One of the more elaborate constructions in the book is for a huge astronomical clock featuring more musicians (including drummers) who played the hours, in part so the faithful would know when to pray. It tracked the moon and sun, and was able to compensate for the change in the length of day and night over the course of the year.

“Castle Clock” astronomical clock.

The book is beautiful and filled with mechanical wonders. The link above to the wikipedia entry is worth following–it describes the different mechanisms employed in al-Jazari’s work, all the cams and pumps that make these devices go.

It may be easy to think of al-Jazari as an isolated genius, a quirk of a culture we now too often reduce to political terms, but he wasn’t the first Islamic engineer of such magnitude, and he wasn’t alone. Check out the earlier creations of the Banu Musa brothers, who developed their own time-pieces in the ninth century and also wrote a treatise on geometry.

And a quick perusal of the wiki page for inventions in Islam brought up this quotation: “Syrian Al-Hassan er-Rammah’s manuscript “The Book of Fighting on Horseback and With War Engines”(1280) includes the first known design for a rocket driven torpedo.” Which even I didn’t know about. As is often the case with historical research, the more I look, the more I learn. Here’s an overview on the topic of science and technology in Medieval Islam by the Museum of the History of Science at Oxford.

In fact, the early Middle Ages are often considered a golden age of technology in Islam. What happened? War. The crusades of Christendom, and the advances of the Mongols assailed the empire on multiple fronts and forced an interest in other pursuits. Religious intolerance and violence on all sides broke centuries of learning and culture. Did that time set up the on-going prejudice and mistrust that flavors current relations between the western world and the Islamic one?

My father is himself an engineer. At a gathering of fellow engineers from all over the world, he reflected, along with a small group of new acquaintances, that one key way for the West to confront and defeat terrorists would be to target the people who create devices like IED’s, car or vest bombs, and other small-scale weapons. They realized they were speaking of engineers targeting other engineers. . . a sobering thought on an occasion marked by international cooperation and good-will.

I don’t have a conclusion for this one, except to wonder what might be achieved for the world if we were able to create a new golden age when human ingenuity might once more be employed for delight and awe.

September 2, 2016

Finding a new Vernacular: the Language(s) of Fantasy

I have spoken to a fair number of people who say they don’t read fantasy because of all the funny names–including agents and editors who are thrown off by too many made-up words. This is one reason I recommend authors pare down on the invented words, especially in, where they really aren’t helping you out. But today, I’d like to think about a different question of language in fantasy–the words of the story itself.

At a workshop at Readercon, the brilliant and amazing Mary Robinette Kowal remarked that what we think of as “transparent prose style” is, in fact, just white middle-American public school English. It is not magic. It is not a given of the rules of grammar or even of good writing that this “transparent style” exists (if it does). The remark opened my eyes in a couple of ways and made me wonder if transparent style is even a worthy goal to pursue, or if, perhaps, I just need to revise how I think about it.

I tend to prefer writing that is relatively unadorned. I think the goal of transparency in prose is for your words to readily dissolve into images and adventures in the mind of the reader. The prose should be transparent in the manner of a window that allows the reader to look through into the world of the characters you are creating. The words should not call too much attention to themselves, or it’s like distorting that glass or perhaps framing it with something distracting. Muddy style, with excess phrases, convoluted sentences and hard-to-follow metaphors can so obscure the writing that it ceases to be worth the reader’s effort to view the story beyond. But I am thinking now that, once the prose rises above that level of distraction and confusion, perhaps a different ideal for prose is in order.

Good writing should be able to illuminate the mind and heart of the author. In my own work, and more generally in the genre of fantasy, most fiction is told through a third-person, close point of view narration, as if a camera rested on the shoulder, or just inside the head of a specific character for the duration of a scene. (For those of you non-writers, this contrasts with either first-person narration using the “I” or head-hopping, where the narration skips around through a variety of perspectives within a scene.)

But the narration, to be true to the nature of the character, should be tinted by that character’s understanding of the world, their own attitudes, fears and worries, and their experience or expectations of the scene itself. The glass should be colored by the words the author chooses and by the details being portrayed to lend weight to the perspective of the individual character. This is often done in very subtle ways, such that the reader isn’t really aware of the narrative bias–allowing them to be more carefully manipulated by a skillful author, absorbing the perspective as if by osmosis. Sometimes, it is done much more obviously–as in an op-ed piece in the newspaper where the writer strongly states how they feel about something, and the reader who agrees might find little to object to, while the reader who disagrees would point out every bit of prejudicial language.

The idea of transparent style being born of public school and wide-spread publishing practice suggests that there are many voices being left out or ignored because they adhere to a different standard for language usage. These other vernaculars–languages commonly spoken–are starting to emerge in fantasy, with some striking results. Sometimes, it takes a little while before the distinctive voice in a work can begin to dissolve into the window through which the story is viewed. But I increasingly believe that adopting a prose style that more clearly colors the text can result in a deeper relationship to the story world and its characters.

If you are wondering how this, shall we call it, translucency of language operates in a fantasy context, allow me to recommend a couple of books. For a step into the Western side of the vernacular, check out Ariane “Tex” Thompson’s One Night in Sixes and its sequel, Medicine for the Dead. These beautiful and moving works settle the reader into the views of a variety of characters whose thoughts and language are clearly marked by their origins in a sidelong version of the American West.

And if you’re ready to step further outside, then check out Kai Ashante Wilson’s novella “A Sorceror of the Wildeeps.” The story itself centers on a dangerous expedition across a jungle teeming with rumor and magic, and the language Wilson uses to tell it creates a surprising and dynamic relationship with the characters. Fantasy fiction is meant to transport the reader, and this one uses some of the familiar tropes of fellowship and quest that hit the fantasy reader’s happy spot. But it takes the idea of transport one step further, by transporting us into an alternative approach to the language of fantasy itself. It’s a worthwhile journey, and one I’m glad I took.

August 14, 2016

Fundamentals for Life

I was recently cleaning up my hard-drive and reorganizing a bunch of files, deleting old things and, not coincidentally, searching for some of my idea notes for a new project when I came across a file entitled simply “Fundamentals.” I thought it might pertain to the drumming workshop I take (“Taiko Fundamentals”) but it turned out to be a list of reminders to myself. And so, I share them with you, and hope, in doing so, that I won’t forget them again.

Since this is a quasi-inspirational post, it seems appropriate to pair it with an inspirational image: I took this shot of Long’s Peak from the Flattop Mountain trail. Someday. . .

Fundamentals

Be present with family and friends.

I feel better when I write.

I feel better when I exercise.

I deserve to be healthy and fit.

Listen with both ears.

Drink a glass of water upon waking.

Posture matters.

If I feel tired, cranky or dispirited, I need to drink more.

Protein for breakfast.

Be thankful.

“You are never given a wish without also being given the means to make it come true. you may have to work for it, however.” (Richard Bach, Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah)

Do the hard parts first.

Share joy.

Surrender to the legos.

I have worlds enough and time.

Be open.

Pursue adventure.

I am who I am because I dare.

August 5, 2016

The Problem of Plagues. . .and other Medieval Usage Issues

I am working my way through my editor’s notes on Elisha Mancer, book four in The Dark Apostle series, and encountering the difficulty of words. Words are, in a novel, the primary tool for delivering the story. In a historical novel, they take on a special significance because selecting an appropriate word for the historical context can really make the sentence spark and the work feel right. And selecting the wrong word will annoy readers in tune with the history.

Which brings me to the problem of plagues. The Biblical plagues of Egypt, for instance. In modern parlance, “plague” retains a similar sense: a plague is, as the OED puts it, “an affliction, calamity, evil, scourge” (a plague of locusts, a plague of survey callers, etc.) But many readers of medievally set historical fiction immediately leap to a single meaning of the word, which came into use around 1382 to refer to a pestilence affecting man and beast. And “the plague” wasn’t conceived as a specific entity until the 1540’s. But basically, I can’t use the word in its more general sense because of the era the books are set. (for more about *that* plague, check out my previous entry on the Black Death versus Ebola)

But my difficulty with language then versus now doesn’t end with the plague. There is also the problem of things being lost in translation. Saints, that is. While we now use the word “translate” to refer exclusively to taking words or ideas from one language into another (sometimes metaphorically), the origin of the term is actually the transfer of a religious figure from one location to another, as a bishop who moves to a different see, or, more frequently, a saint or saint’s remains taken to a different church. It is this idea of holiness being moved or removed which brought the word to its present meaning, because the first work translated was the Bible itself.

Broadcast is another interesting example. Nowadays, we are used to broadcast news, a television or radio phenomenon by which information is shared. It’s actually a farming term, referring to the sowing of seeds by hand over a large area–the literal casting of the seed. But most readers, finding the word in a medieval historical context would leap to entirely the wrong impression. And so, rather than submit to a plague of criticism, I seek a good alternative.

July 30, 2016

Elisha Rex by E. C. Ambrose @ecambrose | @kurtsprings1 #review #darkfantasy

Author: E. C. Ambrose Book: Elisha Rex (The Dark Apostle #3) Published: July 2015 Publisher: Daw Genre: Fantasy Source: Paperback Rating: Synopsis: Elisha was a …

Source: Elisha Rex by E. C. Ambrose @ecambrose | @kurtsprings1 #review #darkfantasy

July 22, 2016

Review: Touch, by Claire North: a deeply human and highly satisfying thriller

This is one of the rare books that I finished and thought–That is what I want my books to feel like. For me, it delivered a powerful emotional impact along with the ripping story and engaging characters. It’s the kind of book that made me want to race around forcing all of my friends to read it. No, seriously, read this book!

Kepler, our protagonist, can assume the minds and bodies of others through a touch. They (gender is intriguingly fluid for such entities) are one of a small number of people who discover they can do this. Some of those entities now live for the moment, bouncing between lives with no compunction about what happens to the people they leave behind, without memories of the occupation or what they did during that time. Some deliberately abused the power, but Kepler actually forms partnerships with their hosts, often agreeing to help them through a difficult circumstance–like an addiction the host suffers from, but which Kepler does not. So first of all, I enjoyed the elaboration of this premise, looking at all of the ways the power could be used.

When we first meet Kepler, their host has just been shot in an assassination attempt by a shadowy organization. Kepler is furious because, although the attempt was aimed at them, the assassin deliberately killed the host instead of leaving her alone after Kepler jumped to another body. Kepler determines to discover who wants them dead and why. After a few jumps in a fascinating chase scene, Kepler succeeds in jumping into the assassin himself. But while in a body, they have no access to the memories or thoughts of that person. In order to questions the assassin, Kepler must jump into someone else after securing the guy so he won’t get away.

Thus begins a very interesting relationship. It is exploitative? How would you feel to have someone take over your mind, then leave you behind? How would it feel to be on the other side–a disembodied personality assuming temporary identities?

I felt the author did a very convincing job of creating Kepler as an individual, and building all of these fascinating interactions with hosts and with others–many people don’t even know this is possible, and the few that do have widely varying reactions to it. There are some great twists along the way to a highly satisfying conclusion.

At a recent convention (I believe it was World Fantasy 2015) one of the speakers pointed out the way that a speculative fiction work reflects the world view of the author. This really got me thinking. . .so I think one reason I admire but don’t enjoy George R. R. Martin’s work is that his world view is significantly different from mine. I am ultimately a humanist (in spite of my “you don’t want to be my hero” tagline and often rather grim subject matter), and believe in the potential redemption of both individuals and humanity as a whole.

I found Touch to be very life-affirming on top of its adventure narrative. Read it because it’s a thriller that will leave you breathless. Read it because it’s the story of complex relationships that develop in startling ways. Read it because it will make you question ideas of identity. Just read this book.