Geof Huth's Blog, page 19

January 6, 2012

The Beauty of the Buttocks

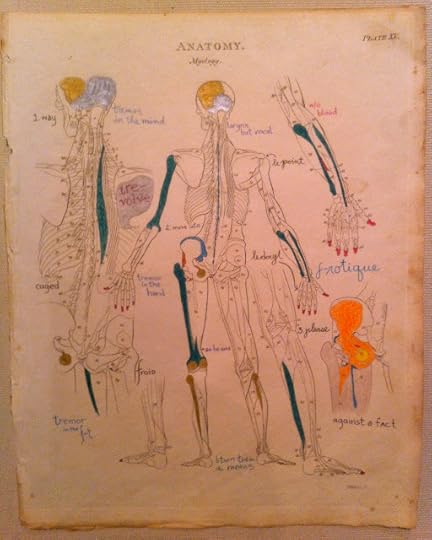

Geof Huth, Detail from "Myology, Plate XV" (6 January 2011)

Geof Huth, Detail from "Myology, Plate XV" (6 January 2011)The attempt I'm working on now is a set of seven plates removed from a damaged book. (I've never seen the book, only these plates.)

Being black and white images, with frequent voids, most of these will be easy for me to color, so I am bending down close to a pages, eyeglasses and contacts away from my eyes, and working like a diamond cutter on the page.

Because I'm still working on the first page, after almost a week.

I consider the poeticity of this as I work. What is the poetic value of a coloring-book poem, even if ex post facto, rather than ab ovo (all white and open)? What about the words scattered in it? How do they cohere into a poem?

And do I care about coherence in the narrower, linguistic, sense?

One could make an argument that the colors in a poem need to function linguistically for the poem to function as a poem, that they must have some, at least quasi-, semantic function. I wouldn't make that argument. In a visual poem text can work as text and/or image, and image can work as image and/or text. It is all possible. It is the possibility that matters, that makes the visual poem worth a stare.

The colors in this poem carry out many important functions (functions that go through my head as I work on this--so much more slowly than I usually do, but always adding color and words every day): Colors demonstrate anatomic patterns across the mise-en-page of the poem, and they protest against such pattern. Colors demonstrate the diversity and complexity of the human body. Colors capture and settle the eye.

And maybe the last is the most important, since for a work of visual art to work it must still the eye enough to gain the attention of the mind.

The text in this poem is entirely semantic and generally syntactic. But the text works nonlinearly. This poem is not stanzaic, but there are often short stanzas in it, and they are always broken into bits and strewn across the text. Reading is meant to occur as view does: by seeing the whole thing but immediately focusing on small bits of it. Reading should be a darting, a looking for bits of color and extracting information from it.

Everything here is of color. It is meant for the sighted and uncolorblind. It is meant for the eyes first, but for the brain in the end.

Mindless, we are nothing. Mindful, we are too cautious. Minded, we are right.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 06, 2012 20:52

January 5, 2012

tracings . . . leavings . . . inklings . . .

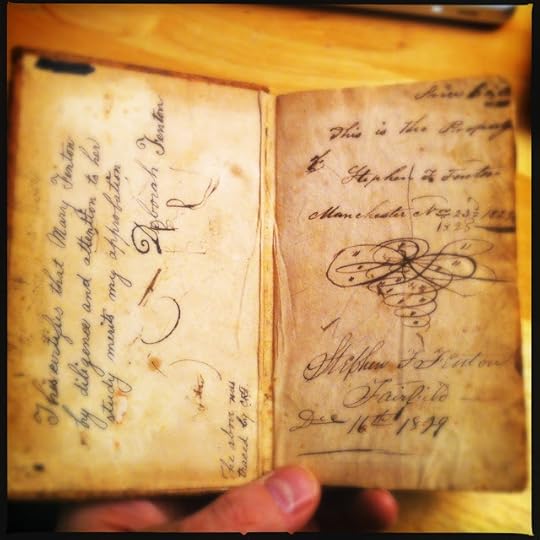

Bibliographic Epigraphy in John Walker's Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language (1823)

Bibliographic Epigraphy in John Walker's Critical Pronouncing Dictionary and Expositor of the English Language (1823)Tracings we leave behind. What we leave are tracings.

Tracks of a finger, ink as spoor. Black footprints muddied out.

We leave behind because we are left behind. A fair child, they might say of one of us, but a far sight shy of a good one.

Snow is a kind of darkness. Paper, the remains of the forest once all upon us, yet now we drag our feet, our nibs, across its fair surface.

No foxes (too shy), but foxing. Paper darkens like snow. Anything to eradicate, anything to wipe the scent of spraints. Brown fur slips into brown water.

We are what is not often of water or sky and given over to the earth best at the end.

Burial of the spirit in the word. Burial of the word on the page. Burial of the page in the fire.

Wrinkles of the hand cradle the pen, wrinkle of the ink soaks the page, wrinkles of the page crawl into a fist.

To trace a word as signature, to trace a word as drawing, as paraph, as flourish and flourishing. To trace a thought from the start. To trace a word from the heart.

From the heartform organ flows blood of ink, inkling of black as a tracing rivulet. Not railing but waiving.

Waving what flag that there's be a surface for the ink sopped up, black ink, red ink, soaked into the cloth, soaked into the page, soaked into the cotton fibers of his shirt. Last in thought of bellum, not belle, but bell, a tolling, still he wrote a word of ink.

Upon the page in warp and wharf, an only mooring from the sea, in black and boiling. What splashes up and splashes him. He's covered top to foot with ink, covered all the body all in words, words in wonder, wander, wade, words with weapons and with blade.

Words' profusion, it is so great, that body (paper, page, and flag), waving, teeters, flagging, falls, and flails as words, in ink of blood and blood of ink, as last retreats and forward's march, leaves the entry that's exit's wound.

Body worded, body inked, the grave tattoo of drumming dimming, the breath is leaving, breast that's heaving, yet every word it ever took, and every word it ever said, and every word it ever wrote, stays behind like mark of shadow.

What's solid's fleeting, yet we leave it behind.

Leave behind a word to mark it. Leave behind a word to be.

All these tracings in the snow. Words' erasings, less that no. Less than none and less than nothing, less than empty and left than bare.

We leave behind, after all our racing, we leave behind to slow our pacing.

We leave behind the word to mark the place we were and that we were. We leave behind for, in the end, we are the words we were and marks, we are the scrapings on the mat, we are the leavings where we sat.

A word in ink is blood of life. We leave behind the word for wordlings. We leave behind the word to prove—that we were left behind and left.

❦

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 05, 2012 20:57

January 3, 2012

My Myological Method

Geof Huth, "Myology, Plate XV" (draft made on 3 Jan 2012)

Geof Huth, "Myology, Plate XV" (draft made on 3 Jan 2012)My muscle is me, even if we thought the muscle were the mouse. What rises through the body, in rising and dipping waves, rocking never cresting, are the physical impulses of our minds, but we are that body.

I thought of muscles as I sat at the table, in light not quite bright enough, to color as a child might with pencils, and to write the occasional word or phrase, on a slightly foxed plate removed from a damaged book, the holes where the needle and thread went through it still visible along its left edge.

It is a process I do not like: to create something atop a unique piece of anything that I like, anything that I think is already beautiful. And I think I've already destroyed this sheet beyond salvage, but I'll keep adding to it until I think it is saved or I believe to a degree that I don't yet that there is no chance to save this thing.

The process of creating a poem on a beautiful piece of damaged paper is frustrating for me because I don't trust my hand enough. And on this page I already see many infelicities of the hand, many times when my muscles (or, sometimes, my pencils didn't work for me. Usually, it is where the text I've written is too large, so I've learned something to guide the next six experiments.

For I have seven of these sheets, each different, to work on. The process should take me more than a month. I may give up in between, but I'll keep trying, because there's always the chance of success. And there is something calming about carefully filling in voids with color. Soon this sheet will be shimmering with competing colors. At that point, maybe it will be something.

For now, it is a hope, an inclination. I hope the incline goes up instead of down. But, of course, that depends entirely on which direction I choose to walk.

On the third day of the year 2012, Geof Huth discusses a visual poem he is creating upon a plate removed from a damaged book on anatomy.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 03, 2012 20:49

January 2, 2012

Pick a Card

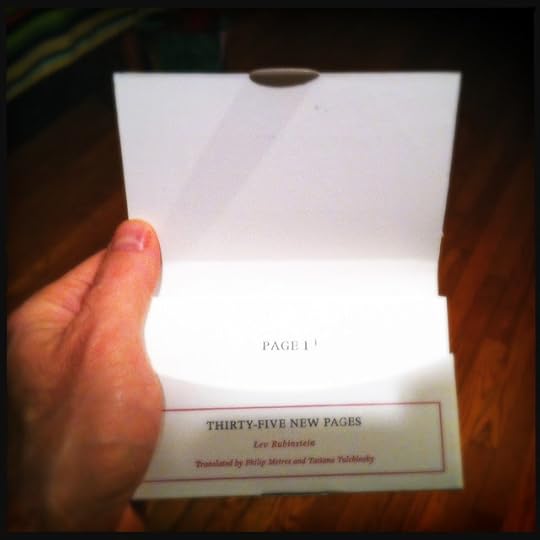

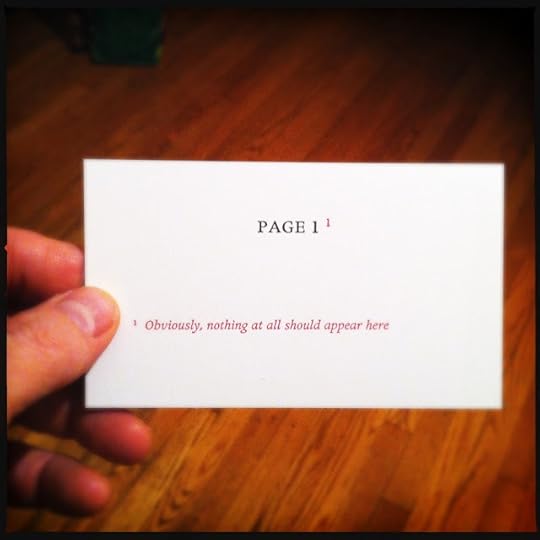

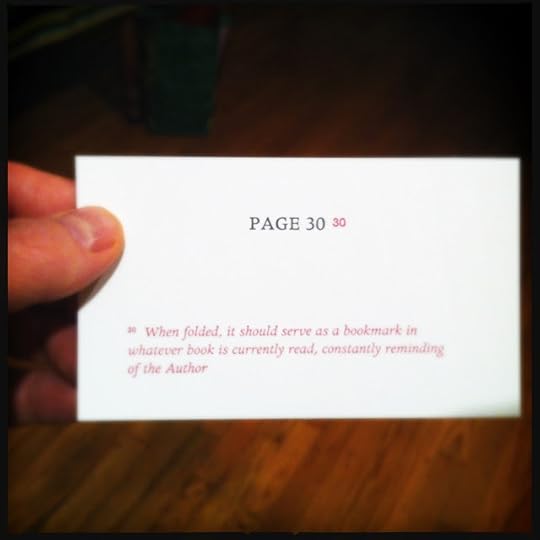

I am drawn to books of poetry on cards, and I didn't realize it until today. Robert Grenier's Sentences . Susan Howe's Poems Found in a Pioneer Museum . bpNichol's still water . The many many works of poetry that Márton Koppánny has produced on cards. To that list, I will now add Lev Rubinstein's Thirty-Five New Pages , recently published by Ugly Duckling Presse.

This is a book to manipulate, a tactile book, haptic. It gains value by forcing us to deal with the pieces of it. But it comes at us, as you can see above disguised as a codex, bearing even its title on its spine, which you could slip between two other tiny books and not recognize, without close inspection, that the book is a box.

These thirty-five cards work through a process of repetition, the slow working out of a thought with few words. Each card is a page numbered, the number appearing at the top of the page as a title. And every title has a small superscript number bearing the same number as the page. And each of these superscript numbers directs you to a footnote, and each of those footnotes tells you what should be on the page, not what is there, but what should be.

As we might guess, the first card should be blank, a blank flyleaf before the title page, and then the numbers pull you into the book that is nothing but a deck of stiff cards in our hands. Rubinstein plays games with you as thoughts slowly and indefinitely arise from the sturdy pages in your hands. "Here," you read in the fourteenth footnote, which appears on Page 14, "something should be written," and you realize it has been. These are conceptual games, but serious, and satisfying. I smiled broadly near the end of the book, filled with a kind of joy at the beautiful rendition of the book's own genius in my head.

I am reminded most, in these cards, of the work of Márton Koppánny, which is also conceptual in this playful way (though also much more visual in intention), and that is a good thing. This text is clean, emotionless, without subject, because it is all subject, because it is about us, about the act of reading, and about the expectations we bring to any process of reading. The book may be a bit pricey given its size, but the joy of reading it doesn't diminish with time.

I'll end, though, with two quibbles: the box itself is far too thin. It needed to have been much sturdier. Books in boxes usually have much stronger boxes, and this one even shows some creasing from merely being assembled by hand. Second, the translation is really not perfect. Maybe this was intentional, but a number of times near the end of the book the text simply isn't idiomatic English. Read Page 30, "is currently read" should be "is currently being read" and "constantly reminding of the Author" should be "constantly reminding one [or you or us] of the Author." I can't imagine a need for this clumsy English.

Still I love the book. It was the first I read this year and the first I reviewed, and it's from Ugly Duckling Presse, and it has a number in its title, and I'm sure it will be one of my favorites of the year even by the end. Just as last year the first book I read and reviewed was a book from Ugly Duckling Presse that had a number in its title: Sarah Riggs' 60 Textos.

I see a pattern, and that is what this book is about: the patterns of reading, the patterns of being, the patterns of expectation.

_________

Rubinstein, Lev. Thirty-Five New Pages. Translated by Philip Metres and Tatiana Tulchinsky. Brooklyn, N.Y.: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2011. US$15.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 02, 2012 20:54

January 1, 2012

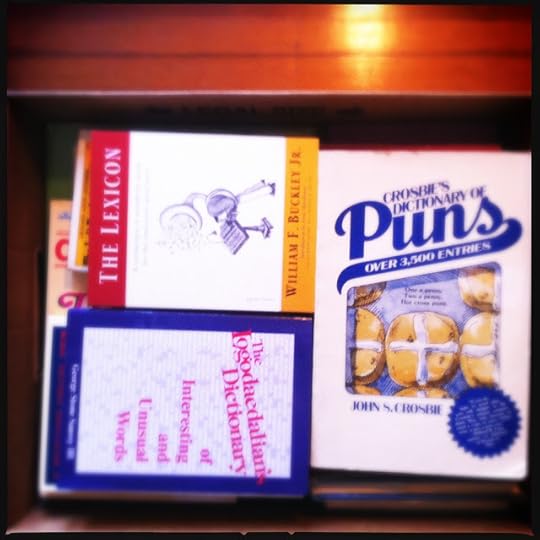

Huth Collection of Wordbooks (A Description)

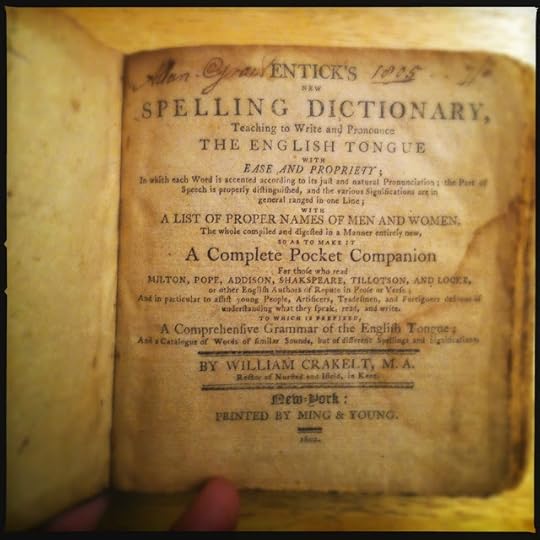

Entick's New Spelling Dictionary (1802)

Entick's New Spelling Dictionary (1802)General Description

The Huth Collection of Wordbooksis a collection of a couple of thousand publications focused on the examinationof language. The core of the collection are about 1800 dictionaries of varioustypes, from the 1700s onward, but the collection includes all other types of"wordbooks" as well: encyclopedias focused on language, thesauri, grammars, "spellers,"usage guides, style books, books on wordplay, and monographs and books of essayson language. The collection includes expensive and rare hardback books, cheappaperbacks, printed ephemera, and even some humorous dictionaries collectedfrom the Internet. The primary focus of the collection is on English, but itincludes books that focus on the entire universe of languages, and it includesa number of bilingual dictionaries, and a number of monolingual works inFrench. The collection covers the history of language, writing systems,phonetics and phonology, etymology, wordplay, and handwriting, making it muchmore than a collection of dictionaries. Its temporal coverage begins in the mid-1700s, with a fewbooks, is strong in the 1800s and 1900s, and already includes many from the2000s.

The core of the core of thecollection is a set of antidictionaries, or recreational dictionaries. The mostfamous of these is Ambrose Bierce's Devil'sDictionary, but the process of collecting these dictionaries has uncoveredan almost secret history of antidictionaries, reaching back far before Bierce.The antidictionary is divided into three sub-categories:

contradictionary: a humorous or cynical glossary that re-defines aset of standard words (such as Bierce'sDevil's Dictionary)

neolexicon: a glossary of neologisms (such as Rich Hall's Sniglets or the glossary thataccompanies Anthony Burgess' novella, AClockwork Orange)

paraglossary: a glossary of words that are either obsolete or rareenough to be entertaining or, in rarer cases, are presented to reveal theirinteresting characteristics, such as strange etymologies or rare features ofconstruction, as in words only one letter in length (such as Josefa Heifetz' Mrs. Byrne's Dictionary)

These antidictionaries themselvesserve as exemplars for the idea that the meaning of words is slippery, thatlanguage is our essential skill yet it gives up on us constantly, that languageis not simply work, but that it also play. The collection as a whole serves todemonstrate how humans are people of words, dependent on them, driven by them,and always using them, even when those words contradict themselves, cause themtrouble, or lead them astray.

Because this is a collection ofpublications, the book as object is of interest in the collection. For thatreason, the collection has multiple editions for many titles, and in some casesit includes multiple printings as well. This tendency towards comprehensivenesshas the advantage of demonstrating small changes between printings and to helpmake distinctions between various printings.

A Few Highlights of the Collection

The strengths of the collection, beyond antidictionaries, are American andAustralian lexicography, British and American books on language, Frenchantidictionaries, and slang. Given that the collector of these books has livedin the United States during the active construction of this collection (fromabout 1992), the focus on American dictionaries is expected, but the Australianpart is not. Still, the collection includes a number of important books in thehistory of Australian lexicography, including a first edition of Edward Morris'Dictionary of Austral English (1898),which marks the real beginning of Australian lexicography.

Because of the expansiveness ofthe collection, it includes scholarly texts in linguistics as well as popularbooks written more as entertainment (or admonition) to the general public.British writers on language heavily represented include the academic writersEric Partridge, David Crystal, and Tom McArthur, the more popular Ivor Brown.American academics include Jesse Sheidlower and Mario Pei (the latter knownbest for his popular books on language), and the popular writers Paul Dickson,Willard R. Espy, and Margaret Ernst.

The collection of Frenchantidictionaries is notable for including an important work of Frenchscholarship that collected examples of invented words from the breadth ofFrench literature. Beyond this, the collection contains a number of humorous,and sometimes quite popular, French contradictionaries, including ones focusedon medicine and pottery.

The slang and dialect segment collectionincludes many contemporary works, including those of the great American slanglexicographer Tom Dalzell, and works of historical importance including earlydictionaries of Americanisms and the second an third edition of Briton JohnCamden Hotten's The Slang Dictionary fromthe 1860s. The dictionaries of slang include serious slang dictionaries, suchas the many editions of Eric Partridge's Dictionaryof Slang and Unconventional English, and many small and humorous glossariesof slang thrown together as entertainment.

Because of the collector'sinterest in family words, in words that are unique to individual families, thecollection has almost as good a collection as in possible. It includes bothrare editions of George William Lyttelton's Contributionstowards a Glossary of the Glynne Language (documenting the words peculiarto his wife's family), all editions of Paul Dickson's Family Words, Adams, Charles C. Adams' Boontling: An American Lingo (documenting Boontling, that jargononce spoken in the tightly knit Anderson Valley of California), the collector'sown Familiar Words: How We Speak AloneTogether (documenting three interconnected strands of familyspeak), and acouple of his friend J. James Mancuso's manuscript dictionaries of words fromhis own family.

Beyond these general categories,the collection includes a number of items of special interest, ranging from agood collection of "blueback spellers" by Noah Webster and others to JohnCleland's questionably accurate AdditionalArticles to the Specimen of an etimological vocabulary (1769). Also ofinterest are an early edition of Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the EnglishLanguage, various editions of dictionaries by Joseph Emerson Worcester(Webster's major competition in the United States), and Noah Webster's firstdictionary, A Compendious Dictionary ofthe English Language. (1806). The collection even includes an interestingselection of dictionaries meant for children, including recent ones doubling ascomic books and A Dictionary, or Index toa Set of Cuts for Children (1804), the latter unfortunately stripped of thecuts, or engravings, that bear mentioning in the title itself.

The Archival Connection

In the end, this is a collectionof books, of objects one holds in ones hands, of things one must manipulate tomake them work. To some degree, these are archival works. Many of them bear themarks of those owners and users who have come before, and often the spellers,grammars and dictionaries from the 1800s include jokes, riddles, and personalnotes, sometimes showing the expressiveness and liveliness of the young womenusing them, such liveliness maybe sometimes being more acceptable within theprivate pages of a book than in real life. Some of the books in the collectionare merely pieces of ephemera, such as little samizdat antidictionaries pastedto bulletin boards. These pieces are interesting in that their content (likethose of the chain letters that came before them) changed over time, being addedto and subtracted from but still remaining essentially the same.

The books also, however, connectto the papers of the collector Geof Huth, which also reside at the M.E.Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives. First, these are thebooks of language that Huth collected, each of them demonstrating his interestin language. Second, a number of the books in this collection are ones he usedas a child or student. They bear his signatures. They preserve his markingswithin their pages. They even show the awards he received. Finally, these books did not exist asan undigested multitude for Huth. They were of a piece. He maintained adatabase that collected up to 45 different pieces for every book, includinginformation on when and where they were bought and for how much. The notes inthe database often put the books into greater context, and the fact that hetracked the names of previous owners of these books helps to show that hesometimes collected more than one wordbook from someone collecting such booksyears before he was.

Potential Use

The collection is broad in scope,despite its focus, and can support many kinds of use. There is enough depth inthe collection to support some linguistic, lexicographic, and lexicologicaluse. The collection as a whole provides evidence of linguistic change, in termsof the meaning of words and phonology, and the collection provides an overviewof the history of the dictionary in English from the mid-1700s on. Certainly,the collection provides plenty of useful material for the study of the book,including changing styles of bookmaking over the years, and it provides assource of practice for those interested in working with rare books. There is aliterary component as well, since many of the writers of these books onlanguage were also writers of fiction or other literary forms. The books alsosupport the study of social history. This partly comes out of the fact thatsome books bear scant but still illuminating information about the users of thebook. But what is more important is that these books demonstrate somethingabout the development of the middle class. In most families in the 1800s, itwas common to have only two books: a Bible and a dictionary. And the dictionaryserved to tell you how to be a proper citizen: how to spell your words, how touse your words, and how to pronounce your words correctly. Over and over again,for more than a century, these wordbooks give evidence that people saw a greatneed to learn to pronounce even the words they used daily. The dictionary, nowan engine of description, was once an engine of prescription that guided peoplealong the right path. And as more various waves of immigrants washed upon ourshores, that desire to use the language properly, at least properly accordingto someone, was an overwhelming desire of those anxious to succeed in society.

The Future of the Collection

This collection of books is notfinished, and only the death of its progenitor can ensure it will no longergrow. Currently, a small but essential part of the collection remains in thecustody of Geof Huth for his continued use. Beyond this, his collecting willcontinue. Even after years of collecting, there remain gaps. The coming yearswill allow time and opportunity to fill these gaps and to add newly publishedworks to the collection. Even in the tiny realm of the anti-dictionary,hundreds of books could be added to this collection. Also, the collection willneed an influx of heavily used dictionaries and grammars from the 1800s to providemore insight into people's connection to dictionaries and language.

Cataloging the Collection

The database that accompanies thecollection provides full bibliographic information, including descriptions ofthe physical state of each book, and up to three dollar values assigned to eachbook: the book's original price, the price I paid, and the current (oronce-current) price of the book in the antiquarian book market. Entries in thedatabase provide enough information to distinguish any book in the collectionfrom any other, even if one of the same edition, and the wealth of informationin the database supports various types of searching. Even unexpected pieces ofdata can sometimes prove useful, as the collector himself often used the nameof a previous owner of a book to find a particular book he was searching for.

[Later, I will include a datadictionary explaining every field in the database.]

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 01, 2012 20:58

December 31, 2011

2,000 Books and Subtracting

75 Boxes of Books, 7 of Personal papers, 2 Tubes of Oversized Materials, and 1 Large Envelope of Oversized Materials Ready for a Trip to the University at Albany (29 December 2011)

75 Boxes of Books, 7 of Personal papers, 2 Tubes of Oversized Materials, and 1 Large Envelope of Oversized Materials Ready for a Trip to the University at Albany (29 December 2011)While preparing this year's donation to the M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives at the University at Albany, my largest ever, I stayed up the entire night to finish my preparations. Even after starting months ahead of time and spending all my free time working on completing the cataloging of these books and the foldering of my papers, I found myself pressed for time. By the time my day was done, I had been away for 32 hours. Starting at about 3:30 that afternoon, I slept for the next fourteen. Among what I gave away were many books I never thought I could ever part with: Noah Webster's Compendious Dictionary from 1803, the first dictionary he ever published; Contributions towards a Glossary of the Glynne Language, both editions of this first-ever book of family words, the first released in 1855 in an edition of 50; Ambrose Bierce's Cynic's Word Book, the precursor to the publication of the Devil's Dictionary, this book goes only through the letter L; a full-leather copy of a high school printing project from the 1940s that included bits of papyrus tipped in; and so many more rare and wonderful and sometimes expensive books.

We are often surprised by the things we give up, which end up being those we must give away. My house was so full of books that I couldn't find the ones I owned. At least 60 boxes of books were piled away in closets and under the eaves. They hardly existed. Many of these were always out in plain view, and I would examine them occasionally and marvel at their existence. I spent years collecting these books, often to the great detriment of the family finances, and I did it to define a world for myself, one constructed of words. The books I collected stretched back to the mid-1700s, and the latest book in the collection is dated 2012 (which won't be here until tomorrow, but such are the habits of American publishers, of all publishers, for all I know).

<iframe src="http://player.vimeo.com/video/3442082..." width="440" height="248" frameborder="0" webkitAllowFullScreen mozallowfullscreen allowFullScreen></iframe>

In my video documentation, I say there were 1825 books in the boxes, but the number was really 1925. However, I reviewed the thousands of entries in my database of books (AKA the Bookbase), and I discovered a number of books not properly marked as heading out of the house, so the real number of books ("titles" is a better term here) is over 2,000. A large number.

The core of this collection is dictionaries, primarily in English, but also in other languages, particularly French. But the collection has any kind of publication concerned with language: thesauri, grammars, style guides, monographs, books of essays. And there is a second, deeper core to the collection, something even stranger. In the collection, there are over 500 antidictionaries, which are dictionaries designed primarily to entertain than to instruct. Some are focused on redefining words in the language (such as the three dozen or so versions of Bierce's Devil's Dictionary within that collection), some invent and define neologisms, and some of them merely display strange or obsolete words for our entertainment (most famous among these probably being Mrs. Byrne's Dictionary). The variety of these (particularly in terms of quality) is huge, and I have these in a couple of other languages, including a good selection of antidictionaries in French.

Or had. I had.

Some of the Books in the Collection and My Jigsaw-Puzzle Method of Packing them in Boxes (29 Dec 2011)

Some of the Books in the Collection and My Jigsaw-Puzzle Method of Packing them in Boxes (29 Dec 2011)Finding these books took both skill and luck, and there are still many more I want. Even now, I've been thinking of the books I need to acquire, of ways to expand the collection. There are big holes in the collection. I have Hotten's second and third edition of his Slang Dictionary, but not the first. I've never found a first edition of The Devil's Dictionary I would buy because it is usually found only in Bierce's multi-volume set of Collected Works, which was sold only as a set. I sometimes have the first volume in a two-volume set without the second, and I somehow allowed myself not to notice that the fifth volume of the Dictionary of American Regional English has recently been released. I'll be particularly interested in that volume, since it will probably include citations from a dictionary of mine, just as the fourth volume did.

The Contents of Box 38 (29 Dec 2011)

The Contents of Box 38 (29 Dec 2011)In this collection, there are many volumes that cost quite a bit of money (and many more that cost almost nothing, but which accrue value by having been brought together), and Box 38 has the greatest concentration of such books. Not many books, but worth about US$5,000 in total. I didn't pay that much for them, though I did pay quite a bit for them. I have tended to live dangerously, at least financially. Still, even this box's books represent only a small percentage of the total value of these books, and I mean "value" in a couple of ways. What is important to me is not the dollar value of the books; what I care about is how these books demonstrate and examine the human engagement with language, how they define us as beasts of the word.

Wordbooks on the Left, Taking up Most of a Row of Shelving (29 Dec 2011)

Wordbooks on the Left, Taking up Most of a Row of Shelving (29 Dec 2011)Once I arrived at the University at Albany, I backed the truck up to the loading dock, and the five or so of us there unloaded this huge collection of books. The process was fairly quick, but tiring, since I'd spent the morning, with Nancy helping, moving 82 heavy boxes down three flights of stairs and into a truck. Once the boxes were moved into special collections, I helped load them on boxes, and then I was ready to go. I said goodbye, drove the truck back to the rental place, drove the car back to the house, made two other donations (one of about 200 books to the public library), and I kept working until I decided to lie down for a few minutes and didn't arise for fourteen hours.

In my dreams, I know there were words.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 31, 2011 19:17

December 24, 2011

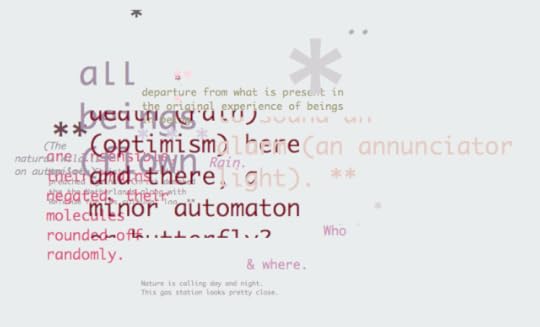

(each asterisk is a snowflake)

(Every link here is the same link and takes you to Jack, even that for the image above of that same poem.)

Today, it is Christmas, even at 2:00 am, which is when I'm starting this. mIEKAL aND is awake in his bed in the middle of Wisconsin thinking of the coincidence of his own birthday with Christmas, with the Mass for Christ's birth. And Jack Kimball is off in nondistant Massachusetts putting together words that are wry, arch, and wary all at once. Little children are dreaming, and some of those dreams are nightmares.

Given the specialness of this day (it is my friend mIEKAL's birthday, after all), I am breaking my blog silence, a silence brought on not by lack of interest—but by the demands of the back-breaking job of cataloging or confirming the cataloging of two thousand or so books (on words, words, words) that I'll be donating to the University of Albany next week. Sometimes, life intervenes. And when it does, even urge and verge cannot take control of our lives. We must live these lives instead.

And, so, a Christmas tradition continues—and one of my favorites: I present to the world (or that little portion of the world that ventures to this small place) Jack Kimball's annual Christmas poem, which is always a digital poem of some kind. This year, it is a marquee poem, a poem created using the marquee tag for HTML. This allows Jack the opportunity to scroll words past our eyesight, and he does this for us in different colors, and with different typesizes. The world is, after all, multifarious, and it comes at us in many flavors, and from many directions.

And all at once.

Words move from left to right, they move up, they move down. And we are left alone to figure them out. Language is a Babel (babble, bubble, bibble, bib, bip, ip). When the letters and words descend from the top of the screen, there is a difficulty putting them back together, because the bottom of the sentence comes first, so we try to stitch the sense back together, but we keep forgetting the recent past, we are not puzzle-solvers, and we are left with fragments.

Because the world comes at us in fragments, some of them gentle, some of them fast, some of them hard-edged, some of them soft. The world is atomized, the particles nothing but the sneeze of God (the sneeze, moreso, of the universe).

In this poem, Christmas comes at us, as snow, as the view we have of light, of a night scene, of the votive candle and the dead, as the Christians modification of the pagan world, of the pagan world we cannot leave, of a sense of blood and breath, body and bone, as a realization of the mind working through the contradictions of culture.

Culture is a mold, spreading.

Some realize it is a kind of night.

(To think that Jack wrote me, about this poem of his, that "this seems more seasonal and escapist.")

Merry Christmas.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 24, 2011 23:25

December 13, 2011

A Poetics (# 87 via # 57)

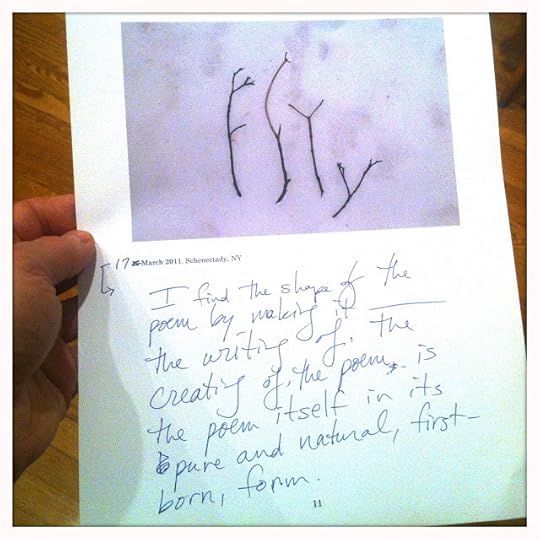

Geof Huth, The First Form of Entry # 80 of "A Poetics" (17 March 2011; photo: 13 December 2011)

Geof Huth, The First Form of Entry # 80 of "A Poetics" (17 March 2011; photo: 13 December 2011)What is, I am asked—sometimes with an intensity vergingon malice, sometimes with contorted confusion, sometimes out of an innocentcuriosity and desire to know—is the boundary between a poem and everythingelse? I am asked this question because a poem to me can be words arranged inlines on a page, words spoken into air, words scrawled on a page or moving on ascreen, shapes resembling letters but never taking the full form of text, songswithout the courtesy of words, or grunts and groans and nothing more—just theinarticulate articulations of the voice.

And I ask, What is the boundary between your body and theworld?

Does sound not enter your body and becomeindistinguishable from your thoughts? Are you not, even now, sucking air intoyour body, bringing the world into your body, just for the simple pleasure ofliving? When you eat the foods of the earth, when are they simply meat and eggsand apples, and when are they merely the substance of your body? the muscle ofyour arm, the hair of your neck, the nail grown just the nail, grown just a bittoo long, of your thumb?

And when you die, when are you no longer yourself? At themoment of death when your consciousness gives way to cosmos? At the point whenyour body becomes the temperature of world around it? When all the flesh hasfallen from your bones? Or when even your bones have crumbled away intonothing? After having defined yourself as a body for so long, when does yourbody not define you at all?

The more precise the line between poetry and somethingelse, the less I care about it. Not because I don't find the exerciseinteresting. I do. But because poetry has to be about possibility, andboundaries are more about pietics, about purity of thought instead of theelasticity of possibility.

But poetry means something to me—as a word withinquotation marks and as a concept.

Poetry is that art that we practice that has an intensefocus on language in any of its three incarnations (or any combination ofsame). In visual poetry, the focus is on the shape of the text, which mayinclude images, which may be wordless, which may consist of nothing butinvented textshapes. Visual poetry examines poetry primarily from the point ofview of the eye. In sound poetry, the focus is on the sound in the ear, so a soundpoem heightens the aural and may be about intense verbal gymnastics in terms ofmeter or music, or it may be about the examination of the sonic edge oflanguage: the sounds we can make that have no verbal meaning but which we canpronounce in ways that allow it to carry emotional meaning.

In textual poetry, sometimes called lexical poetry, whichis what most people think of when they think of poetry (that is, poetry inlines that sometimes is read alone, in loping cadence, from a page), the earplays a part because the poem is about the sound of words even when notsounded, the eye has its place because the poem's arrangement on a pagegoverned its expression from the body and gives silent hints to its meaning,but the poem is primarily for the mind, for the making of sense or thedestruction of sense through sense: it is about the meaning we make when wehear through the syntax of words held in place together.

Certainly, all of these are of the body and affect thebody, and all of these are of the mind, and force us to think, but these arealways emotional products of the self. We are meant to understand them with ourbody, with our mind, and with our heart, which are all the same thing, each oneindistinguishable from another, each more a concept than a fact, each the mostimportant pieces of our unique selves, themselves indistinguishable from theswirling mass of the universe twisting around us.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 13, 2011 20:59

December 10, 2011

At the Sight of the Bruise

Bruise on My Left Thigh (29 November 2011)

Bruise on My Left Thigh (29 November 2011)It all started when I fell up the stairs.

It is so more likely for someone to fall down the stairs that I always have to emphasize the word "up" when I tell this story.

I am now weeks into a project to pack up 2000 of my wordbooks (dictionaries, antidictionaries, thesauri, grammars, usage guides, and even monographs on all aspects of language). These I will be donating to the University at Albany in the next couple of weeks, and I never imagined the dangers to my health that such a project entailed.

One day a few weeks ago (the 20th of November), I was carrying two heavy boxes upstairs. (These were actually boxes of my papers, which is the other part of this project.) Just before I made it to the landing, I slipped on the stairs, the weight of the boxes helped pull me down faster, and I landed hard on the corner of the second from the top step with the outside of my left thigh. One of the boxes spilled its contents onto the landing, so I cleaned that up and then I lay down for a while, keeping ice over the point of impact. I went to bed early that night.

The next morning, my leg was still sore, but not much. I had no bruise on my leg at all, and as the days passed my pain slowly subsided. Then on the morning of the eighth day after my accident, I sat down on the toilet and noticed a brand new bruise on my leg, but on the inside of my thigh. It was large, deep purple in the center, flaring out into red, and dissipating finally into that sick shade of green associated almost entirely with bruises.

I thought it amazing that it took over a week for the bruise to show, especially since I had imagined I wouldn't be bruising. After all, I don't bruise easily.

What I didn't realize was that, along with the bruise, I would begin to experience greater pain. Suddenly I had pain that centered on my thigh and calf but that went all the way down to my ankle. The pain was frequent but not constant. It would change places suddenly and without notice. I began to limp.

Eventually, my leg began to seize up, especially if I didn't use it. When I stood after sitting for long periods of time cataloging books to donate away, my leg would cramp up, making the first step with my left leg painful. Worst of all, my leg would cramp up when I slept, and I would away to painful burning cramps six or so times a night.

This past Monday, I decided to visit the doctor, electing to take an appointment late in the day. Yet it wasn't late enough. After waiting thirty minutes past the time of my appointment, I went up to the woman at the counter and asked if I'd been lost in the shuffle. The response was that I was next, and that they hoped they would be able to get to me soon.

And soon enough they did. The nurse weighing me told me she liked my tie, a subtle pattern of ladybugs that people rarely recognize as such.

I didn't see my doctor but a physician's assistant named Kathleen, and she couldn't figure out the problem. She was very thoughtful, asked questions, and allowed me to ask questions, but she didn't know why the bruise took so long to show and why it showed on the opposite of the leg, and further down as well. She told me to take three ibuprofen twice a day, and to call if the situation worsened. She was adamant about this directive, because she'd quickly learned that I'm only vaguely interested in my health. I think she realized this during this conversation:

Kathleen: What medicine's do you take?

Geof: I've no idea. There are too many of them?

Kathleen: You don't know the names of your medicines?

Geof: No. You know how some people are really interested in their health? I'm not one of those people.

Kathleen: Well, you really should know what medicines you're taking. You should keep a list with you.

Geof: I'm never going to do that.

Kathleen (looking in my thick patient folder): I see you take [and she names a bunch of medicines I don't remember the names of now].

Geof: I remembered that two of them had almost the same name. And see? I don't need to remember them. You can look them up.

Kathleen: You need to know your medicines. What if you go to an emergency room, and don't know your medicines?

Geof: I'll never go to an emergency room again.

Kathleen: Why not?

Geof: Because it's always a waste of time.

Somehow, I did not annoy her with my natural obstinacy. I did ask questions, though they were focused on figuring out why the bruise took so long to show. She said I was the most analytical patient she'd ever had. I said I was paid to think.

She also sent me deeper into the hospital for an ultrasound of my leg. I asked, "Is this so we can make sure the baby's okay?" She didn't answer, but maybe she laughed. She was sending me for an ultrasound so that we could discover if I had deep-vein thrombosis (which is a serious condition that can lead to death) or phlebitis (swelling of the veins).

After waiting in two more waiting rooms, a sonographer named Amy conducted the test of my leg. It was a bit boring sitting there without a screen to show me the veins she was following. And she told me that, if I had deep-vein thrombosis, they wouldn't let me leave the hospital. They let me go, but without telling me what the results were.

The next day, I discovered I had superficial vein thrombosis, which is associated with no dangers.

Later that day, however, I called the doctor again and set up an appointment, because the bruise started spreading, popping up in a non-contiguous part of my leg. This seemed like worsening, so the call seemed necessary, though I wasn't at all sure.

This time, my own doctor ("Joey," I called him) showed up, entering the room while saying, "Let's take off the leg!"

"That's what I thought!" I said.

(The man knows me a little, so he can tell jokes.)

He decided that what happened was that the fall damaged the entire muscle group in my thigh, and that this caused bleeding internally that was slowly spreading through the leg (downward apparently because of the force of gravity). He assumed that the bruised had been spreading because the ibuprofen was a blood thinner, so he took me off that regimen and told me not to take my daily aspirin for a week either.

And Kathleen gave me a prescription for a heavy painkiller. I still awoke to cramps the first night I took them, but the dosage in the morning kept me groggy all through the work day, though my pain didn't decrease. I reduced the diurnal dosage the next day.

My pain has slowly subsided over the next few days, though I'm not sure if it was the painkiller alone that made that happen, or if my leg is improving. The bruise is dissipating, so maybe the leg is getting back to normal. Still, I limped for a little bit today.

I received the painkiller in a container with warnings stuck all over it, and until a few minutes ago I thought there were only three warnings. But I have just discovered that one of the warnings was pasted over a fourth:

DO NOT DRINK ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES WHEN TAKING THIS MEDICATION.

Hmm, would've been good to've known about that a few days ago.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 10, 2011 19:26

December 4, 2011

On Metadata and Metalife

The Fifteen Boxes of Wordbooks Ready for Donation (5 December 2011)

The Fifteen Boxes of Wordbooks Ready for Donation (5 December 2011)After weeks of working at it, weeks of searching the house for dictionaries and other books of language hiding in nooks, weeks of putting them into boxes, I have not prepared exactly 15 boxes of an estimated 80 or so for donation to the University at Albany.

The process is complicated by two major factors:

First, years ago, I abandoned entering information on each of my books into my database of books, because I'd switched back to Macintosh computers and had not purchased a database program for that environment. I still haven't, but I've found one ancient functioning Windows laptop, and I'm updating the database there. The data I collect on each book is quite extensive, so I have spent many hours collecting metadata on books I'll soon no longer own.

Second, I have never finished covered the dust jackets of each dustjacketed book I own. Certainly, this is a ridiculous process, and one more ridiculous when I'm focused on books I am about to give away, but it has the value of protecting the books from damage (or further damage), no matter where they exist.

Unfortunately, I've been working on this project, various parts of it, for months, so I should be further along. But it's more complicated that simply books. I'm also preparing my papers for donation. And even though a good percentage of those are in perfect order, quite a bit remains unorganized. When I'm not working on organizing books, I'm focused on organizing my personal papers, and I have three boxes of an estimated ten of those in perfect order. But about half of what remains is in order, they just don't fill entire boxes yet.

As part of my papers, I'm organizing the digital files relating to these papers, primarily digital audio and video, though I may also prepare collections of digital photographs for donation as well. All of which takes time, even though most of these collections are in nearly perfect order.

Just as I have pulled too much data into my life, I have created too much data during it. And all of this information is somehow information about my life, metadata about me.

So that I do not so much live a life of flesh and blood and sex and hunger as I lead a life of data, in multiple formats both digital and analog. If the data all disappeared, I myself would disappear, even if my breathing body remained.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 04, 2011 21:26