Huth Collection of Wordbooks (A Description)

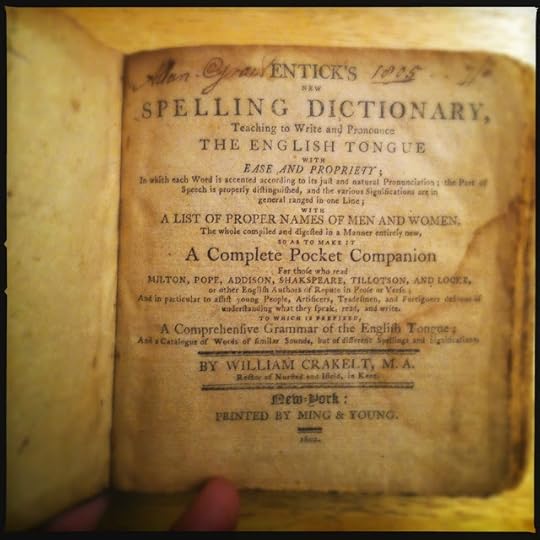

Entick's New Spelling Dictionary (1802)

Entick's New Spelling Dictionary (1802)General Description

The Huth Collection of Wordbooksis a collection of a couple of thousand publications focused on the examinationof language. The core of the collection are about 1800 dictionaries of varioustypes, from the 1700s onward, but the collection includes all other types of"wordbooks" as well: encyclopedias focused on language, thesauri, grammars, "spellers,"usage guides, style books, books on wordplay, and monographs and books of essayson language. The collection includes expensive and rare hardback books, cheappaperbacks, printed ephemera, and even some humorous dictionaries collectedfrom the Internet. The primary focus of the collection is on English, but itincludes books that focus on the entire universe of languages, and it includesa number of bilingual dictionaries, and a number of monolingual works inFrench. The collection covers the history of language, writing systems,phonetics and phonology, etymology, wordplay, and handwriting, making it muchmore than a collection of dictionaries. Its temporal coverage begins in the mid-1700s, with a fewbooks, is strong in the 1800s and 1900s, and already includes many from the2000s.

The core of the core of thecollection is a set of antidictionaries, or recreational dictionaries. The mostfamous of these is Ambrose Bierce's Devil'sDictionary, but the process of collecting these dictionaries has uncoveredan almost secret history of antidictionaries, reaching back far before Bierce.The antidictionary is divided into three sub-categories:

contradictionary: a humorous or cynical glossary that re-defines aset of standard words (such as Bierce'sDevil's Dictionary)

neolexicon: a glossary of neologisms (such as Rich Hall's Sniglets or the glossary thataccompanies Anthony Burgess' novella, AClockwork Orange)

paraglossary: a glossary of words that are either obsolete or rareenough to be entertaining or, in rarer cases, are presented to reveal theirinteresting characteristics, such as strange etymologies or rare features ofconstruction, as in words only one letter in length (such as Josefa Heifetz' Mrs. Byrne's Dictionary)

These antidictionaries themselvesserve as exemplars for the idea that the meaning of words is slippery, thatlanguage is our essential skill yet it gives up on us constantly, that languageis not simply work, but that it also play. The collection as a whole serves todemonstrate how humans are people of words, dependent on them, driven by them,and always using them, even when those words contradict themselves, cause themtrouble, or lead them astray.

Because this is a collection ofpublications, the book as object is of interest in the collection. For thatreason, the collection has multiple editions for many titles, and in some casesit includes multiple printings as well. This tendency towards comprehensivenesshas the advantage of demonstrating small changes between printings and to helpmake distinctions between various printings.

A Few Highlights of the Collection

The strengths of the collection, beyond antidictionaries, are American andAustralian lexicography, British and American books on language, Frenchantidictionaries, and slang. Given that the collector of these books has livedin the United States during the active construction of this collection (fromabout 1992), the focus on American dictionaries is expected, but the Australianpart is not. Still, the collection includes a number of important books in thehistory of Australian lexicography, including a first edition of Edward Morris'Dictionary of Austral English (1898),which marks the real beginning of Australian lexicography.

Because of the expansiveness ofthe collection, it includes scholarly texts in linguistics as well as popularbooks written more as entertainment (or admonition) to the general public.British writers on language heavily represented include the academic writersEric Partridge, David Crystal, and Tom McArthur, the more popular Ivor Brown.American academics include Jesse Sheidlower and Mario Pei (the latter knownbest for his popular books on language), and the popular writers Paul Dickson,Willard R. Espy, and Margaret Ernst.

The collection of Frenchantidictionaries is notable for including an important work of Frenchscholarship that collected examples of invented words from the breadth ofFrench literature. Beyond this, the collection contains a number of humorous,and sometimes quite popular, French contradictionaries, including ones focusedon medicine and pottery.

The slang and dialect segment collectionincludes many contemporary works, including those of the great American slanglexicographer Tom Dalzell, and works of historical importance including earlydictionaries of Americanisms and the second an third edition of Briton JohnCamden Hotten's The Slang Dictionary fromthe 1860s. The dictionaries of slang include serious slang dictionaries, suchas the many editions of Eric Partridge's Dictionaryof Slang and Unconventional English, and many small and humorous glossariesof slang thrown together as entertainment.

Because of the collector'sinterest in family words, in words that are unique to individual families, thecollection has almost as good a collection as in possible. It includes bothrare editions of George William Lyttelton's Contributionstowards a Glossary of the Glynne Language (documenting the words peculiarto his wife's family), all editions of Paul Dickson's Family Words, Adams, Charles C. Adams' Boontling: An American Lingo (documenting Boontling, that jargononce spoken in the tightly knit Anderson Valley of California), the collector'sown Familiar Words: How We Speak AloneTogether (documenting three interconnected strands of familyspeak), and acouple of his friend J. James Mancuso's manuscript dictionaries of words fromhis own family.

Beyond these general categories,the collection includes a number of items of special interest, ranging from agood collection of "blueback spellers" by Noah Webster and others to JohnCleland's questionably accurate AdditionalArticles to the Specimen of an etimological vocabulary (1769). Also ofinterest are an early edition of Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the EnglishLanguage, various editions of dictionaries by Joseph Emerson Worcester(Webster's major competition in the United States), and Noah Webster's firstdictionary, A Compendious Dictionary ofthe English Language. (1806). The collection even includes an interestingselection of dictionaries meant for children, including recent ones doubling ascomic books and A Dictionary, or Index toa Set of Cuts for Children (1804), the latter unfortunately stripped of thecuts, or engravings, that bear mentioning in the title itself.

The Archival Connection

In the end, this is a collectionof books, of objects one holds in ones hands, of things one must manipulate tomake them work. To some degree, these are archival works. Many of them bear themarks of those owners and users who have come before, and often the spellers,grammars and dictionaries from the 1800s include jokes, riddles, and personalnotes, sometimes showing the expressiveness and liveliness of the young womenusing them, such liveliness maybe sometimes being more acceptable within theprivate pages of a book than in real life. Some of the books in the collectionare merely pieces of ephemera, such as little samizdat antidictionaries pastedto bulletin boards. These pieces are interesting in that their content (likethose of the chain letters that came before them) changed over time, being addedto and subtracted from but still remaining essentially the same.

The books also, however, connectto the papers of the collector Geof Huth, which also reside at the M.E.Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives. First, these are thebooks of language that Huth collected, each of them demonstrating his interestin language. Second, a number of the books in this collection are ones he usedas a child or student. They bear his signatures. They preserve his markingswithin their pages. They even show the awards he received. Finally, these books did not exist asan undigested multitude for Huth. They were of a piece. He maintained adatabase that collected up to 45 different pieces for every book, includinginformation on when and where they were bought and for how much. The notes inthe database often put the books into greater context, and the fact that hetracked the names of previous owners of these books helps to show that hesometimes collected more than one wordbook from someone collecting such booksyears before he was.

Potential Use

The collection is broad in scope,despite its focus, and can support many kinds of use. There is enough depth inthe collection to support some linguistic, lexicographic, and lexicologicaluse. The collection as a whole provides evidence of linguistic change, in termsof the meaning of words and phonology, and the collection provides an overviewof the history of the dictionary in English from the mid-1700s on. Certainly,the collection provides plenty of useful material for the study of the book,including changing styles of bookmaking over the years, and it provides assource of practice for those interested in working with rare books. There is aliterary component as well, since many of the writers of these books onlanguage were also writers of fiction or other literary forms. The books alsosupport the study of social history. This partly comes out of the fact thatsome books bear scant but still illuminating information about the users of thebook. But what is more important is that these books demonstrate somethingabout the development of the middle class. In most families in the 1800s, itwas common to have only two books: a Bible and a dictionary. And the dictionaryserved to tell you how to be a proper citizen: how to spell your words, how touse your words, and how to pronounce your words correctly. Over and over again,for more than a century, these wordbooks give evidence that people saw a greatneed to learn to pronounce even the words they used daily. The dictionary, nowan engine of description, was once an engine of prescription that guided peoplealong the right path. And as more various waves of immigrants washed upon ourshores, that desire to use the language properly, at least properly accordingto someone, was an overwhelming desire of those anxious to succeed in society.

The Future of the Collection

This collection of books is notfinished, and only the death of its progenitor can ensure it will no longergrow. Currently, a small but essential part of the collection remains in thecustody of Geof Huth for his continued use. Beyond this, his collecting willcontinue. Even after years of collecting, there remain gaps. The coming yearswill allow time and opportunity to fill these gaps and to add newly publishedworks to the collection. Even in the tiny realm of the anti-dictionary,hundreds of books could be added to this collection. Also, the collection willneed an influx of heavily used dictionaries and grammars from the 1800s to providemore insight into people's connection to dictionaries and language.

Cataloging the Collection

The database that accompanies thecollection provides full bibliographic information, including descriptions ofthe physical state of each book, and up to three dollar values assigned to eachbook: the book's original price, the price I paid, and the current (oronce-current) price of the book in the antiquarian book market. Entries in thedatabase provide enough information to distinguish any book in the collectionfrom any other, even if one of the same edition, and the wealth of informationin the database supports various types of searching. Even unexpected pieces ofdata can sometimes prove useful, as the collector himself often used the nameof a previous owner of a book to find a particular book he was searching for.

[Later, I will include a datadictionary explaining every field in the database.]

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 01, 2012 20:58

No comments have been added yet.