Geof Huth's Blog, page 15

February 23, 2012

Poetry is Everywhere

Just in case you thought poetry was passé, here's evidence that poetry is everywhere, even accompanying packaged rubber duckies dressed up for wedding showers. And what perfect control of meter. And that last line is not creepy at all.

These are good days to be alive.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 23, 2012 20:57

February 22, 2012

Shooting Photographs with a Poem

Dreamlight among Two Buildings on Eagle Street, Albany, New York (20 February 2012)

Dreamlight among Two Buildings on Eagle Street, Albany, New York (20 February 2012)I begin this tonight the way I begin a poem. With no idea of a destination. Because life can sometimes be ambiguous and sweet. Like a poem. Discovery—even if only a possibility, and not even a likelihood—our greatest joy.

When I take a photograph, and I take hundreds a month, I know how it is framed, how the colors work within it, how I've chosen some contrasting feature to demonstrate the invalidity of the homogenous world. But I don't know quite what the photograph will be.

Possibly, this is because I am a poor photographer, though I have spent most of my life practicing. Maybe it is because I shoot most of my photographs with a phone now. (I originally wrote "with a poem," my mind always replacing a word I want with another that somehow echoes it.) Or maybe this is because I never know what my poems will be either.

I never know. Life is a surprise. Art is the surpriser.

Just as I live my life ready to see a good picture, I live it ready to scrape a word or a phrase out of the air and make something else out of it. Art is the disruption of reality. Art is the replacement of reality. The reason I make art, at whatever level I do, is because reality is too unprocessed for me. I want the clarity of art, the focus, even when that focus is hazy or feathers out along the edges.

We make our art for beauty. For beauty's sake. For the beauty it is. The beauty it brings. We bring the beauty into us. And if we think clearly enough about art, we see all kinds of beauty, even dirty and ugly ones. A life is best made out of beauty, and those of us blessed enough to be allowed the option of beauty in our lives are the fortunate ones.

I took no pictures today. Saw nothing I could make a good enough beauty out of. I made no poems out of words in lines, though I recorded the ending poem from a book a finished writing two years ago, but have done nothing with. For the creation is what I want. Distribution is for artists, poets, things like that. My role is to be the art.

I did make a large number of fidgetglyphs today, most small in size, some reasonably beautiful.

And I did little else. A few beers with Dave Lowry, in which poetry never came up (and the guy likes Longfellow). An online chat with Anne Gorrick (who is a poet, but who is currently more obsessed with scents, with perfume, with collecting the ingredients of perfumes and fashioning her own).

Yesterday, I captured dozens of beautiful photographs of the New York State Capitol but have done nothing with them yet.

Life is a river, and it flows past us, or it carries us along. But we do not see it as a string of actions, as a single movement, as a ribbon infinitely extending. We see, instead, fragments, flashes, a photograph here, a word there, a scent that raises our heads and flares our nostrils. We see the flashing of light between the frames of the film. But we do not see everything. We cannot hold onto everything.

So we hold onto what we can and hope we've held on tightly enough, and to the right things.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 22, 2012 20:49

February 20, 2012

Where I Live

Right into the Front Door of the New York State Governor's Mansion from My Apartment (20 February 2012)

Right into the Front Door of the New York State Governor's Mansion from My Apartment (20 February 2012)From one of the three front windows of my apartment, I can see right into the front door of the Governor's mansion in Albany, New York. On occasion, I can watch guests enter the gate at the bottom of a small hill and make their way up a sloping pathway to that door. Usually, however, guests park in the lot at the south end of the mansion, as I myself have done on a few occasions. If I visit the mansion for another event, I will merely have to cross the street.

Even more remarkable is the fact that the Governor's mansion is situated at the southeast corner of the building where I work, so I can sit on my futon and look at the building where I work (the Cultural Education Center). My own office in this building is the only corner office on the ninth floor that I cannot see from this perch, which fact allows me to live a healthy distance from work. From here I can also see much of the Empire State Plaza (that grand conglomeration of state office buildings), including the Corning Tower and the Egg (a performing arts center). Not to mention the Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, where, daily, priests are protecting us from the ravages of contraception. I pass the cathedral every day on my five-minute commute to work (from futon to the chair in my office, including elevator ride).

I have lived here now for seven months, and it is a strange and solitary life, one that allows me much time for writing, but one which has increasingly been taken up with watching movies. Still, I write and create an enormous number of things that I call poems. Somehow, nothing decreases my productivity in that realm. Or everything increases it. On weekends, I rarely speak, and more rarely see, anyone I know. For some reason, I've also lost my massive ability to read. Year before last, I read over 365 books. This year, it's been maybe five books, and all of them quite short.

Yet there are entertainments here. I can report that marijuana smoking (not by me, who has never smoked anything) goes on across the street from the Governor's mansion, and I hate the smell of that smoke more than I hate cigarette smoke. The little dog that lives in the apartment below me is left alone for most of the weekend and cries quietly but annoyingly the entire time it is alone, leading me to play music constantly to drown him out and fill the space. (He's doing a little bit of yowling right now.) I am in charge of snow shoveling here, which reduces my rent a little each month, yet the snow has been so slight in Albany this winter that I really could have dispensed with snow shoveling entirely.

More interestingly and sadly, my next-door neighbors had a row today. A few items fell or were pushed to the floor, but there was no physical fighting, and the poor young woman cried from the other side of my bedroom wall. It was a plaintive cry, the worst kind, the most painful. I have heard such crying before, and I can't help but feel for anyone making such a cry, even this poor young woman whom I hardly know.

One day a couple of months ago, the couple came to my door and asked me if I had heard anything in their apartment that afternoon. I said I thought one of them had run down the stairs a few minutes before, but I learned that an intruder had climbed the fire escape up to their open window, entered the apartment, and ransacked the place. The apartment was filled with the things of life (furniture, decorations, knickknacks), but the filling was made more dramatic by the mess the intruder had made. Something covered almost every inch of the floor.

About a month later, the man was carrying a loveseat (I use that term intentionally) up the stairs, and he introduced me to his friend, noting that I was a very nice guy. I think I am, yet I was not at all sure how I had proved that to this man. I wonder about that sometimes. How do we present ourselves to people? How do they make decisions about us so quickly? There are people I have known for years who have recently come to conclusions about me that showed their decisions were made on assumptions and not facts. I concluded that the man had merely assumed I was nice because I was always polite to him and had tried to be helpful that time I had toured his ransacked apartment.

Since this blog on poetry and art (and the works appearing in the intervening space between them) is also a blog about myself and my personal experiences, and since those personal experiences make up the seemingly fictive component of this blog (I am a character here, not a human), I thought it necessary to report, finally, that I am living alone. It is not a piece of information I have told many people, though some have discovered it without my having told them. I told only one of the people I work with every day, believing it difficult to keep this information from the person I was commuting with to work.

(Of course, I would claim that I've already told people I've moved by giving them the information they need to conclude that I have. Most of the photographs I post include GPS data about where they were taken, and I take many, at all times of the day and night, in Albany. And when I post a recording to Audioboo, and I've done 200 of these so far, the recording comes with a map that often pinpoints exactly where I live. Anyone with the wherewithal could use that data to find my apartment building and throw stones at whatever windows they think are mine. Hint: Top three in the front of the building. But please don't do that.)

This change of venue is a change of life, even if it doesn't last forever, even though I will certainly move somewhere else before I die (unless I achieve death sooner than expected). Being here, I have learned that I am given to minimalism in my life. I don't spend much time at all with anyone now. I have nothing on the walls here, but the place is decorated with plenty of books. I have a good work table, and sometimes I actually sit at it to eat. Usually, my apartment is quite spare and neat. When the poet Jim Behrle came here, he told me this was the nicest place he had ever seen. And, sadly, he wasn't joking.

What I like most about living here is this big room I am in right now, the room where I spend most of my time. The floor is a beautiful blond wood, handsanded by the poet Douglas Rothschild, who is the super for this building and a number of others, and who is amazingly handy and helpful. (When the landlord told me I would have to retrieve the key to the apartment from Douglas, I asked him, "The poet Douglas Rothschild?" and the man was honestly surprised people knew who Douglas was and that he was a poet.) This floor is wide, and I keep it bare and open. That allows me space to dance to some of the music I play: "Anarchy in the UK," "California über Alles," "If I Ever Leave This World Alive," "Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands," "Human."

"Are we human or are we dancers?" As I say, we are both.

And there are other songs.

For now, I am trying to imagine a life as a solitary man, and I'm noting that my skills may lie elsewhere. Fortunately, I was trained to cook when I was a young boy, even making dinners when I was nine and my mother had broken her arm falling while climbing a fence at our house on Lake Erie. For most of my married life, I was the cook, and I learned, eventually, that I enjoy cooking. I know how to clean. The place is neat. And I have no pets or plants to care for or to complicate my life. I will note that I am usually good at taking care of things, but that I want only to take care of people, not inanimate things, animals, or plants. I was raised, as the eldest child of six, to take care of people, which made me good at being a father, though maybe not as skilled at other aspects of my life.

There is something strange about living in Albany, something unexpected, something that even people who know me well might not realize, not even my siblings, I'd guess. I've already lived in Albany. Just not this one. I used to live in the one in Alameda County, the one in California, the one beside Berkeley, the one across the Bay from the place where I was born. And now I live in the Albany in Albany County, the one in New York, the one that is the state's capital, the one where I've worked the vast majority of my working life. I've lived in Albanys at both edges of the continent. It is a strange coincidence.

(And, now, if I could only get Ron Silliman, the only other poet I know of from Albany, California, to move here, then the two of us could share that distinction. Unfortunately, I have a rule that I can never see Ron in this country, so he'd have to live here but make sure we never saw each other. We'd have to call each other all the time to make sure we didn't go to the same movie theater or restaurant at the same time. I've met him a couple of times, but only in England.)

When I was about eleven and attending Presentation College in Barbados (this was before my brother was expelled and we had to change schools and attend Mapps College instead), one of our pop quiz questions (all on things no-one had taught us) was "What is the capital of New York State?" I immediately wrote "New York" on my sheet, only to learn the answer was actually "Albany." How would I know? I'd never lived in New York State. I had never attended school in the United States, except for a few weeks in the second grade. I had left the country when I was six.

And I've just kept leaving one place after another. By my count, the move to this place is the 47th of my life. And my father has moved almost double that many of times. So I have a lot moving to do.

Just as I was finishing this in the dark (as I usually write), I heard steps coming up the stairs, so I craned my head to the right to see how many sets of feet I could see pass through the crack of light under the door. There were two, two sets, two pair. A couple.

(And then, a minute or two later, a set or two left, and I heard the woman's muffled voice in the hallway.)

(everything's always changing)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 20, 2012 20:05

February 19, 2012

Today's Day

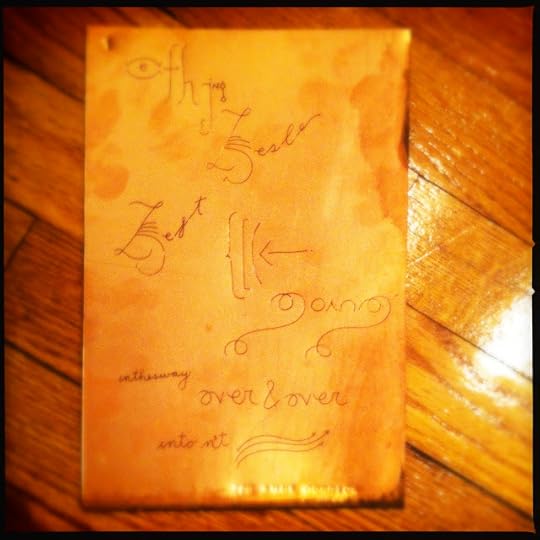

Geof Huth, "dicta (the tongue, the voiceless)" (February 2012)

Geof Huth, "dicta (the tongue, the voiceless)" (February 2012)Today, I accomplished a few things:

I created and recorded a spokepoem entitled "to, merely, be"

I worked for hours on a grant application that is the simplest application I have ever seen, and I did not finish and may not.

I put together a tentative selection of my poetry, one that included my object poem "dicta (the tongue, the voiceless).

I created another fidgetglyph on copper, which is teaching me more about writing on copper.

I opened or closed no door that a human passes through except for one for a bedroom and one for a bathroom.

I finished writing a longish poem seven pages long.

I edited a collaborative manuscript of poems by another poem and me.

I wrote a small number of emails.

I fell asleep around 5 in the afternoon, but only for a short while.

I kept Facebook off almost all day long, but mIEKAL aND had always posted something new whenever I checked.

I made a dinner of onions, black-eyed peas (from France, for some reason), andouille, fried okra, and tomatoes, almost a gumbo but not quite.

I tried to watch a number of movies but succeeded only in watching The Go-Getter, which was a poor title for the film.

I considered but rejected washing my clothes.

I wrote a short essay about the spokepoem I created today.

I wrote two pwoermds.

I listened to music almost incessantly, and it filled the space around me.

I did almost nothing I had planned to do.

I suppose I created five poems today, which is why I assume I've created over 150 poems so far this year.

I reminded myself that quantity does not necessarily have any value.

I forgot everything.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 19, 2012 20:39

February 18, 2012

A Copper-Clad Birthday

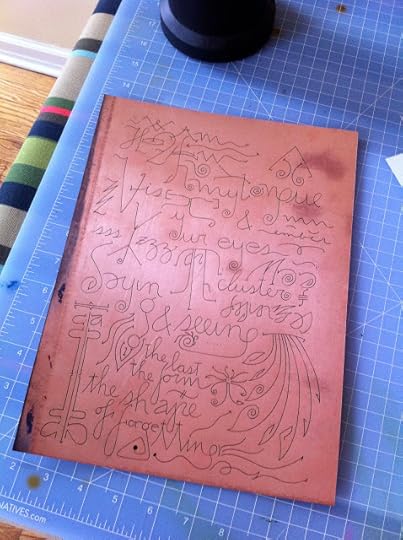

Geof Huth "1. efhjng" (18 February 2012)

Geof Huth "1. efhjng" (18 February 2012)Today is the birthday of my dear friend Anne Gorrick (who is also my deer friend [the number of dead deer Anne and I (well, and her husband Peter, too) and I have been around is staggering (yes, two can be a staggering number)]). She does not like the number of the age she has turned, for reasons I honestly cannot fathom. She says that the number created by adding the two numerals of her age together is huge, but the resulting sum was much larger when she was 39. So you now know she is no longer 39. Nor does she look her age, much younger than mine, at all. Yes, I do not understand. I turned 50 without a whimper, or even a care.

So why spend so much time telling you about Anne's age without telling you how old she is? Just so I can dissuade her from taking note that the birthday present I've made her today is really not good enough.

Geof Huth, "my tongue y/our eyes" (18 February 2012)

Geof Huth, "my tongue y/our eyes" (18 February 2012)I've been working in copper today, and the reason for this is Anne. She has become a fan of my simple jar poems, collections of materials (and a few words) thrown into a cork-stoppered jar. It's good to have a fan, I think, even if incomprehensibly so. I do enjoy the jar poems (each of them a part of the long poem, In Their Collected Beauty), but I doubt they justify much attention. They are beautiful enough sometimes, and to me they are achingly beautiful, but they seem to be hermetic objects instead of affective and effective works of art. What I call aeffective. That is the goal but not necessarily the achievement.

My idea was to wraw giant fidgetglyphs onto the copper, and my first achievement ("my tongue y/our eyes") was relatively successful, but tiring to create. It was so large that it took me at least an hour to create. And it was dense with words, with drawings, with wrawings (not quite writing, not quite drawing). This piece was so much larger and much complex than a usual fidgetglyph that I felt tired afterwards, not physically tired, but intellectually so. I wasn't sure if I had any of this brand of imagination left in me.

So I cut one of the quartered pieces of copper I'd cut (only today) in half, and I decided to use one of these to make a small gift for Anne. This glyphic piece of mine has some good parts to it, but it is not really successful. It does not use the copper page enough, and it seems too direct, too linear, even though, I assume, most people won't be able to read it as easily as I can. To me, it's essentially just a sentence, though there are some nice flourishes here and there.

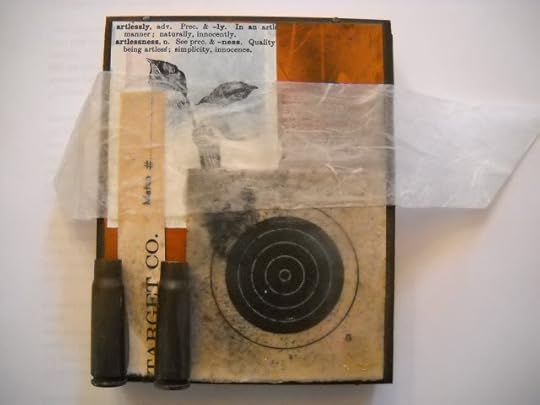

Anne Gorrick, Untitled So Far as I Know, but I Call it "artlessly" (18 February 2012)

Anne Gorrick, Untitled So Far as I Know, but I Call it "artlessly" (18 February 2012)Anne was also working in copper today, maybe as a birthday celebration for herself, and she produced a three-dimensional collage of exquisite beauty (which she tells me is actually better in person). My pieces are done and good enough for a day's work, but Anne's little work is a real achievement. The multimedia aspect of it draws me in, and it holds together remarkably well, visually and semiotically.

Quite a coincidence that Anne and I were both working in copper today? No, not really. She and I bought our copy at the same time, from the same pile of copper in Kingston, New York. She suggested that Peter, she, and I go to a store in Kingston to find materials for my jar poems, and so I did. But we also found this copper, and today is the first free weekend day since we bought our copper.

I made this little present for Anne today to honor her and her talent. Her poetry usually makes me want to sit down, head in my hands, and listen, for she is the most musical of poets, and I mean that literally: I can think of no other poet who works so musically with language. But she is also quite talented in the visual arts, working to produce pieces that I simply love. (Hey, I recently bought five pieces by Scott Helmes and Anne, because they were too beautiful not to own.)

Just so Anne knows that this piece is for her, I stamped "FOR ANNE GORRICK" on it in the lower right corner. And I also stamped the numeral 1 in the opposite corner. Because I imagine a sequence of these poems, in numerical order, each to a different person, and each poem inspired by a desire to send a small gift to Anne.

Well, actually, I think I'll give it to her next Friday, when I see her.

Unless I forget.

Happy birthday, Anne.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 18, 2012 19:46

February 17, 2012

The Stamps, the Stampings, and, Finally, the Stamping Out

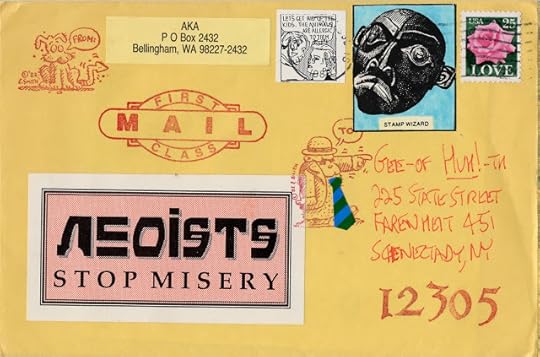

Mail from Rudi Rubberoid (1988)

Mail from Rudi Rubberoid (1988)Rudi Rubberoid died this week, and I realized that I had not heard from him in almost a quarter of a centurty. It's hard to imagine that, once, I was a young man doing something like poetry in a few strange and obscure corners of New York State, and that now I am almost half my life from that time. And it's hard to believe that Rudi Rubberoid, who was one of the well known, productive, and humorous mailartists of the 1980s has been out of the range of my vision for so long. Our last contact was in 1988, about a year after I'd become involved in mailart. I am happy to report, though, that he was almost 85 when he died, so he lived a long life.

Death sometimes reveals more to us than life, and so it is that Rudi's death revealed more about him than I had ever known, such as his real name: John Calvert Palmer, nicknamed Jack. Certainly, it was clear, even to me, that Rudi's last name could not be Rubberoid, but I vaguely assumed that his first name was Rudoph. His obituary puts that misconception to rest and also draws a few unexpected parallels between his life and mine.

Rudi was a native Californian, as am I, though he was a southern California and I'm from the preferred end of the state. His father was in the Foreign Service, as was I, so he grew up around the world: Marseile, Genoa, and Penang (Malaysia). His careers in retail, restaurant management, and picture framing were nothing like mine, but I still feel plenty of kinship with him.

So far as I recall, Rudi and I never never really exchanged pleasantries. Instead, we exchanged mailart. I probably sent him copies of the zines I made frequently in the 1980s, and he sent me his classic rubberstamped and stickered enveloped, brimming with kitsch. Inside the envelopes was more of the same, in place of correspondence, because mail art even when it's called correspondence art rarely includes correspondence.

The envelope above is a good example of his art. It is humorous, artful, and forms a kind of quasi-collage of conflicting information. Rudi even makes a joke on my name, calling me Gee-of Huh!-th, a joke possibly based on the version of my name that I used while editing zines: Ge(of Huth). (I used to use many different versions of my name for different reasons: Geof A. Huth for "standard" poetry, G. Huth for visual poetry, G.A. Huth for haiku, and the list went on.) But Rudi is not making a joke of the fact I lived in Apartment 451 by calling it Fahrenheit 451. That's actually what I called it. That's what I had on my return address stickers.

Rudi was a pure fun mailartist, one focused on connecting, on humor, on color, and always on rubberstamps. He was an artist without any pretensions. He was not infected by the literary pretensions I had. And it was a joy to receive mailart from him.

Something I'll never experience again. Though I don't receive much mailart anymore. I haven't sent much out in about a year, and mailart is about exchanges. If I send nothing, no-one sends anything back. Mailart is a giving of gifts, sometimes a potlatch, which is a tradition from the Pacific Northwest, where Rudi lived in his final decades, specifically in Bellingham, Washington.

Rudi and I have one other attribute in common. He didn't want any public service. I will be the same when I also expire, for I want no service at all. All I want is a cremation and the disposition of my ashes however the living prefer. As I say, life is for the living.

But the dead never quite leave us, not while we're still living. As we continue, as our minds continue, we keep them in our memories, so I've saved a little happy corner in my brain for Rudi. May he rest well.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 17, 2012 20:55

February 16, 2012

In the Beautiful House of the Written Hand

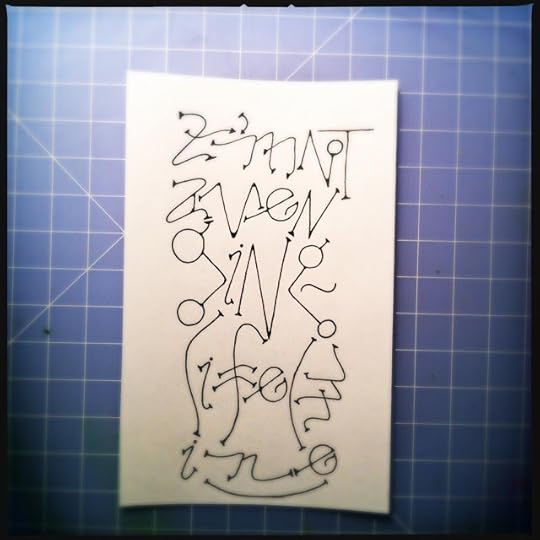

Geof Huth, "2'mNoT" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, "2'mNoT" (15 February 2012)What do you think about the endangered status of hand-writing in some schools' curricula? What effect do you think it has on language art, or language, or art?

(Question received from Jeremy C. Casabella, 15 February 2012)

The hand is a tool, a tooler, a talent.

We say an artist has a good eye, and certainly the eye directs the hand, but the hand must be steady, muscled as it must be, flexible yet sturdy. An artist needs a good hand, which could be either left or right. Or both.

And "hand" may be end of an arm, applause, aid and succor, or the singular shape of a person's handwriting.

Handwriting is how characters acquire character.

Just a few thoughts, scattered about, in answer to a question Jeremy C. Casabella sent me yesterday, but early yesterday, so early that I awoke to it, via my phone, before even rising from bed, a rising I had no desire to manifest. Through the day, while dealing with many other questions from folks about the issues I handle (appraisal and retention of records, travel rules, personnel and their performance, and even questions of such a personal nature that I might not even want to mention I had been asked them), I considered Jeremy's question, wondering forth, in particular, my own connection to handwriting, my sincere dependence on it, as artistic expression, as literary gift, as lifeblood of a life so much made up of the tapping of keys into words.

Still, there is music there somehow.

After passing through depressing manifestations of the self as realized being (whatever the DEFFIL that means), I ended the day, almost that full half of it, with a single meeting, conducted via bellowing phone call from the bulbous belly of my grey and insistent companion, about the national coordination of disaster response for cultural materials. (Such are the rough outlines of my working life, one I find endlessly fascinating, even though I am human and can always imagine an end.) During this teleconference, I began to draw fidgetglyphs that focused on the idea of handwriting. I considered how I wrote out the characters of this Latin alphabet of ours, in all their allographic glory. I examined the value of the the handwritten character.

Truth be told, I seem more interested in the handwritten character of a vehicle for poetry than anyone else. I make a distinction here between the handwritten and the calligraphic. They both might be beautiful writing, but calligraphy (as variously practiced) comes burdened with a different set of assumptions and constraints, many of which I take into account in my use of the handwritten, but none of which accounting turns the tables and changes the balance so that a calligraphic manifestation is evident. (Except when I work directly in the tradition of calligraphy, though that produces calliglyphs instead of fidgetglyphs, and the latter is the better word.)

A fidgetglyph is an extemporaneous dance of the hand, so I do not know the end of it, or even the beginning, when I begin it. I don't not begin with words (and sometimes don't even include them); I begin with shapes that remind me of letters and that may grow into words as my hand explores the visual and semiotic possibilities of those inklings. So the opening character of my fidgetglyph "2'mNoT" may be a numeral 2 or a crossed capital Z or an I. This shows us the power of handwriting to support ambiguity, and ambiguity is the protyle of poetry. We create everything worthwhile out of it.

That little fidgetglyph is more than the sum of its few letters, the words they make in a meandering row into a little sentence. The poem means by being words and letters of a particular shape, which mimic and mirror each other, which form a cohesive but not total symmetrical whole. The gestalt makes it for us. (I exaggerate, believing, as the overwrought creator of the thing, that my extemporaneous creation of the thing allows me insight into how it works, and believing that this carries with it the onus of too many years among the words, the shapes of the words, and the sounds I seem to think those shapes make.)

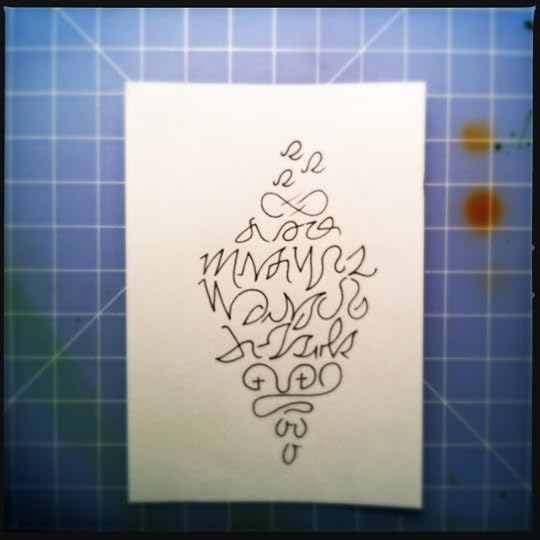

Geof Huth, "R/s" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, "R/s" (15 February 2012)The first fidgetglyph I created yesterday, at the feet of my phone, was a simpler one, wordless, and less successful (though those last two descriptors are not irrevocably tied together in the realm of fidgetglyphing). My experiment here was with ambiguity purely. (As I demonstrated once, years ago, in an old poem forgotten by everyone but myself, I am ambiguilty.)

The three "identical" characters I wrote to represent both majuscule Rs and the minuscule s's that follow them in the recitation of the alphabet. Much of the rest of the fidgetglyph is about the imperfect replication of identical forms, so a line of Ms devolve into W-like forms. Any handwriting is about replicating certain shapes in recognizable forms, but it is also about the ways in which those forms change. For instance, there are often quite distinct characteristics of handwritten letters in their initial, medial, and terminal forms.

This diamond (just about a "lozenge" in early English pattern poetry terminology) is a coalesced examination of these ideas, a practice at written into the ambiguity of it, a poem wordless but larded with the almost instances of words.

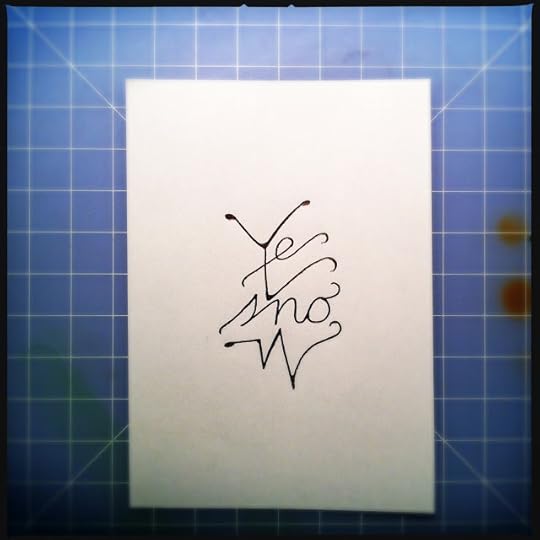

Geof Huth, "Ye" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, "Ye" (15 February 2012)One of the afternoon's latest glyphs was the shortest, but it was also one entirely focused on the cursive hand.

It seems to me that the most beautiful symmetry is, always but in part, asymmetrical, requiring the eye to fix the true and sure symmetry in the mind, but allowing the eye a little revery in the visual dissonance, in the beauty of the imperfect.

So it is that that giant Y, a majestic majuscule, does not perfectly replicate itself, yet, it does, and it echos everything around it: the paraphlike end of the e, shapes that echo down through the terminal flourishes of the o and the W. None of this is accidental; it is the agency of the eye assuming its dominion over the creation of this modest fidgetglyph. (I pause to point out that fidgetglyphs are intentionally modest, their official definition including the requirement that they be "unambitious.")

This is a visual poem, fully visual, embracing its attractiveness to the eye, calling out to that organ of unhearing. Yet the poem is also verbal, intentionally and intensely so. It is a pun, two words strung together into one vocalization, but also a pun, on opposites and on acceptance and desire for. And this vocal element is heightened by its focus on the central phoneme of the five phonemes that make up this poem: the /s/. The sound of that s is drawn out by the s-like flourishes ending the Y and the e that begin the poem. That sound that s, is the sound of snow in the process of being used, not the sound of snow falling, but the sound of skis or snowboards or sleds across the snow, even of the tires of cars rolling through the melting fabric of that fallen snow.

It is the writing, the handwriting, the understanding of how a letter is formed and can be formed and can mean through its various incarnations, that makes this poem work. "Yesnow" is not really a poem at all. It has no exuberance, so there is no way to undercut that happiness with ambiguity or sadness.

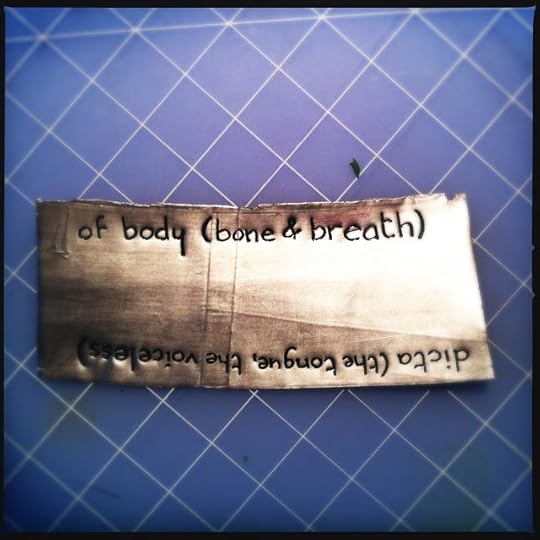

Geof Huth, from "of body (bone & breath)" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, from "of body (bone & breath)" (15 February 2012)After returning home from the day's work, I was still involved in handwriting, I was still focused on the meaning of the word as written out by hand. My goal was to finish a poem of mine, but not an ordinary poem, an object poem, but not an ordinary object poem, but a jar poem, a cork-stoppered jar filled with objects in multiplicities and confusions, but this one was unfinished. It was still absent its words.

The day before, which was Valentine's Day, the day of the heart (even for the heartless or heart-broken or for those with hearts that needed to fail but were stopped by knives and saws and an opening up and replacement of parts), I had written a few appropriate words to add to the poems, only two lines, but designed for this poem:

of body (bone & breath)

dicta (the tongue, the voiceless)

I had imagined that I would handwrite these words on slips of paper torn out of sheets of paper, but something else happen. The fumbling hand of Fate intervened. Inside the suit I was wearing, I found the lead band from a wine bottle, a band taken from a bottle of wine drunk at a restaurant sometime in the past, and taken roughly: I had run a key or the tip of a pen, something not . . . as sharp as a knife, up through the lead, leaving behind a wrinkling cut. The lead was lead-grey on the inside but blood red on the outside, so it seemed to me appropriate for this collection of material.

This jar poem, which is part of a longpoem I am now calling In Their Collected Beauty (but which I had only recently been calling Every Poem Ever Written, a more dramatic but less outrageously pretty title), contains my most disturbing of collected items. The most so are a partial human jaw and human teeth collected from a graveyard surrounding a church in Rohrbach-le-Bitche in Alsace, France, the source of my Huths, including my great-great-grandfather Johann Huth who traveled to New Orleans in the 1850s only to die young in that bowl of pestilence, as generations of my ancestors did, young, only 43 years of age. When I visited Alsace (and West Germany and Corsica) on a genealogical trip, in 1985, I ended up in Rohrbach and found the entire graveyard around the church dug up, gravestones toppled and broken, bones and jaws and teeth church up out of and lain upon the earth. It was a shocking discovery, but I collected a number of pieces of the dead from this site: a lower jaw, a palmful of teeth, a partial skull pan, and two porcelain Christs on the cross, both broken from the wrenching open of the graveyard ("cemetery" being too heady a word for such a small collection of graves). When I picked up these pieces of humanity, I realized that they might have been ancestors of mine, that they were likely relatives.

I placed all of these pieces except for the piece of a skull (which was too large for the mouth of the jar) into the jar, and I added to it a number of other items: Quite a few camel's teeth that I had procured while living in Somalia, a few of them drilled at one end so I could fashion them into keychains; the upper jaw of some small rodent; a tiny glass jar, stoppered with the tiniest of corks, and holding a small grey-blue seasnail shell; a small perfume bottle found in my backyard, empty but irisdescent from its life within the chemicals underground in a houseside midden; and a bottle of Chanel No. 22, nearly empty, nearly evaporated, but potent enough that if I open the larger encompassing jar, my nose is met by a smell more redolent that even the death that occupies that glass jar.

So it is that my two lines of poetry complete this poem of objects. This is a poem about the human body, and the bodies of all the small animals surrounding it, a poem about the body, which is created of the substantial and persistent bone and the evanescent and disappearing breath, and which is made whole by those two parts of being. This is a poem about speaking, about the things the tongue says, and about what the bone remaining (after the tongue rots away) cannot say. It is about saying and not saying, seeing and not seeing, about what we can hear and read and about what we can no longer hear and read, because the human body, and the mind held within it as a warm and edible mass, has slipped away into nothingness.

So my handwriting, for this poem is simple. It is printing, but also simplified printing, regularized handprinting. Its letters are bonelike, being as formed as they need to be to be understood. The cross of the t never crosses the t.

The way a word is written by the hand is how it means.

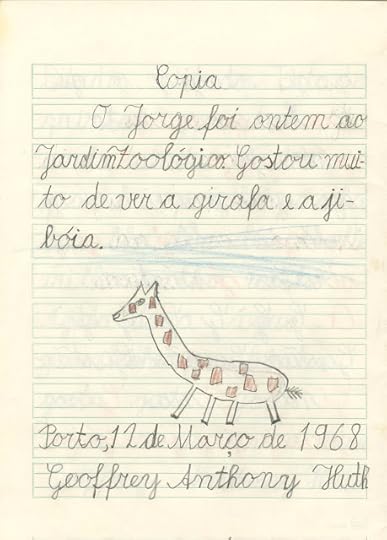

Geoffrey Anthony Huth, "Copia" (12 March 1968)

Geoffrey Anthony Huth, "Copia" (12 March 1968)Two weeks ago, my friend Scott Helmes, one of the most talented (and, thus, most modest) of artists I know, visited this area to attend the opening of exhibition featuring dozens of collaborations between him and my good friend Anne Gorrick. Sometime during my visiting with the two of them, and others, Anne talked about the power of the hand, and the need to use the hand. She believes in what the hand can do when inhabiting an analog world, as do I. She believes that Scott has so trained his hand that he can produce these fluid and floral movements of ink that are utterly beautiful, as do I. And she believes that these handmade things we make are the better forms of art, that the digital is somehow deadened by a separation from the human, as I don't also believe.

So, to answer the question, after thousands of words, I regret any loss of knowledge, especially knowledge, that could lead to the creation of better art, and the loss of training in penmanship is a great one, even though it's one few people take advantage of. We do become, as I fully am, cyborgic by our reliance on machines to make our words for us. But every form of making, whether through digital machines or analog tools, is a possibility, and I do not want to abandon any possibility. Every tool has a set of meanings and a set of potentials that no other too has. So I don't extol the handmade over the machine-enabled.

Yet I am primarily a maker of poetry, visual poetry, by hand, though few realize this. Most of these creations no-one, no-one at all besides myself, ever sees. I make hundreds of handwritten or handmade visual poems a year, easily 500 in some years. They are small, granted, but they are things, they exist, and they persist, if only in folders. My hand is traine to make letters, and still I think my hand untrained for the job.

And I was trained since I was a small child.

At the age of six, while starting my schooling at the Deutsche Schule zu Porto in Oporto, Portugal, my teachers trained me in penmanship in a very prescribed way. Before I wrote any letters, before I wrote connected e's or s's in a row, I wrote shapes in a row. I was taught to repeat shapes and connect them to identical shapes, so much so that by the time I was seven I could write almost completely controlled letterforms around a drawing of a giraffe. Actually, I felt, I could feel in the fragile bones of my fingers, how writing was a form of drawings.

And I learned letterforms that I had to abandon when I returned to North America (though to Canada) to live. I gave up the open-bowled cursive p. I abandoned the curving tops and bottoms of my cursive and crossed majuscule Z. It was a temporary loss, though. Those tilde-like opening and closing strokes of the Z (and other letters) inhabit many of my fidgetglyphs, including "2'mNot," the tilde of which is merely a form reproduced just as I had learned it when I was six. An open-bowled p in a fidgetglyph feels different and means differently than a closed-bowl cursive p. And that H that begins the Huth in my seven-year-old's signature is the dramatic presence of self when it appears in a fidgetglyph. It was a form I had forgotten until I was found it stitched into a pillowcase in a hotel in Peru in 1974.

When I lived in Bolivia in the mid-1970s, I learned calligraphy, and (unlike, I assume, everyone else in that art class) I never gave it up. I have learned to honor the hand, and the handwriting it produces, to honor the careful placement of ink on the page.

Once our culture loses that knowledge entirely, or gives it over entirely into the self-subsumed artistic class of which I am an unwitting but willing part, it will lose part of its ability to read these signs. The same visual text will be before them, but they will see the equivalent of rongorongo before themselves, pictures that must mean something wordlike, but which appear to them as nothing but shapes or pictures, meaningless, but pretty, pretty meaningless, but pretty.

My father has the most controlled handwriting I have ever seen. He never has a rushed hand, though I have one so rushed that it can be almost unencryptable even by me after a few minutes. He presses the nib of his pen, often one of those black Department of State ballpoints that I lived with for so many years, and he for so many more. I think he understands the beauty of his hand, though he has never mentioned it. Instead, he extols the beauty of his father's hand and that of my sister Nini, but their hands are middling. They are workmanlike and readable but without any artistry to them. My father says none of his other children have good handwriting.

He has never, apparently, seen mine, because my need for handwriting is so deep that I see almost nothing but the flaws, my inability to make a perfect circle every time, an unintentional jog in a near-perfect curve extending half-way across a page, one bowl of a two-storey g a bit smaller than the next. I have often thought of artists like myself, artists who work in small ways outside of the glare of attention as nocturnal artists. And I have written almost every single one of these words here while sitting in the dark, with the only light being that of the screen and the keys of the keyboard before me. (This is my only musical instrument.) But artists such as myself, such as most of the artists I care most about, these cryptic and crippled visual poets, I also think of as invisible artist, because so little of our work is seen, because we reject the normal means of art-making for those we love the most.

So we are invisible even as we create things to see, things for the contemplation of the eye, things for the joy of the physical and inky word.

For dinner tonight, I ate one red pear, a hardboiled egg (browned, but peeled down to whiteness), and one half a red tomato. It was a sufficient and sustaining meal for a man of my relatively slight weight, especially after a day of more eating than usual.

While eating these pieces of food, I thought of the curves of their exteriors, the beauty and variability of them, and I imagined the fingers of my right hand drawing them into letters, into words, into meaning, into shapes taken into the body to be made something of there by the human mind.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 16, 2012 16:36

February 15, 2012

Every Life is Symbolic, Not Real

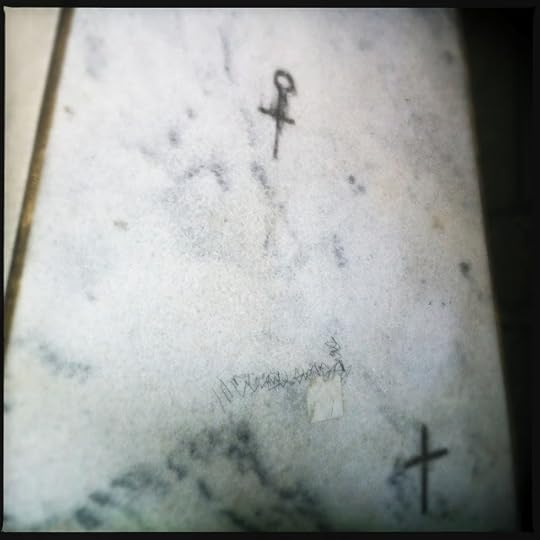

Graffiti on the Cultural Education Center (15 February 2012)

Graffiti on the Cultural Education Center (15 February 2012)On the squared marble column of the building I work in, at the far right of the bank of doors that opens its body to the world, I found today a congeries of rough-hewn graffiti, two bold characters separating an asemic squiggle.

The large characters, each dramatically awry and the topmost written too high for anyone standing on the ground to write, were not characters of any language, but symbols distributing meaning and associations in loud thunks.

Each also resembles the letter t, each replicating the cross.

The lower symbol is, clearly, the cross, a crucifix, a Christian symbol that represents Christianity, Jesus Christ, even the resurrection, itself being the assignment of positive meaning to a simple drawing of a gory instrument of death by slow torture.

The upper symbol almost stands in contradiction to the first: it is the symbol of Venus, woman, and the malleable metal copper, concepts in contradistinction (if not, sometimes, conflict) with Mars, man, and iron.

As the cross represents Jesus (thus, in Christian extension, god), it also represents man, the godhead being given to us as a male being, and the elongation of its vertical line, a spike.

The version of the symbol for woman that we are provided here, however, carries a long spike, which might make us think of the symbol as hermaphroditic, except that there is a separate symbol for that, which combines the male symbol with this on, topping the circle of the symbol with a pointed spike.

The symbolism of the spike is obvious.

But the symbol for woman is less so: the circle represents the spirit (the circle, possibly, representing an awelike O, the expiration of breath from the body), and the cross (which is meant to be square, each line of identical length) represents matter, thus exhibiting solidity, stability.

The extra length of the vertical in this version of the woman gives this symbol a resemblance to the ankh, or crux ansata, the symbol of life (that is, eternal life), thus giving this found text a reverberation between the two symbols, the cross always representing Christ's promise of eternal life.

(Although everyone is granted eternal life in the Christian view—it is merely that some are promised a happy one, and others one of eternal torment.)

The crux ansata was also thought by some to represent the male and the female in one, something alluded to here by the length of that spike.

Between these two symbols on the flat western face of this column, there runs a faint scribble of illegible text, the visual equivalent of gibberish.

Between the woman and the male, the corporeal and the spiritual, the upper and the lower, the human and the god, there persists conflict, misunderstanding, an inability to connect, the pure unalloyed beauty of whatever cannot be interpreted precisely.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 15, 2012 20:52

February 13, 2012

Foodart

I decided to have a real dinner tonight (rather than leftovers, rather than nothing), and one reason for this was that I had to eat my golden beets before their greens went dry and crunchy.

As I was preparing to make and then making the meal, I realized that I was creating it just as I would create a poem—in fact, in much the same way, intellectually and physically, as I have been creating my jar poems for the last few days. (These are object poems created inside jars. I fill these jars with objects, usually in multiples. I often fill the bottles with strata of objects, slipping in just enough words to make a poem out of it.

At work today, I decided that I had to eat my beet greens today, because they wouldn't last long, beet greens are my favorite greens, and they are not always easy to find.

Almost immediately, I decided I needed to eat the beats too (another favorite food of mine, even when they are yellow). My first thought was to boil the beats, layer the greens atop them, and then top the greens with grated Morbier cheese, a slightly strong cheese.

But I knew I wanted lamb too, so I decided to take a couple of lamb chops out of the freezer, though I was not sure how I'd prepare them.

I began the process of taking apart the food: peeling and cutting the small yellow beets, de-stemming the beet greens and cutting off a few dry bits, removing the fat from the lamb chops, and grating the Morbier. I love this process of creative destruction. Nothing can be made with breaking it into parts.

With the beets "boiling" in water and the stove rising to a broil, I decided to add a red pear to this meal, so I cut one up and finished with the actual cooking (the application of heat over time to food).

By this point, the beets were boiling, the lamb chops (covered with a fine mist of pepper and salt on both sides) were broiling, and I was cooking the greens in a little olive oil and butter. I also added finely grated pepper over all of one side.

I transferred the food onto my plate in order: first, the lamb chops, arranged back to back; then the pear slices on either side of the chops; the beets, cooked through, but still offering some resistance; the beet greens next to those; and, finally, the Morbier, but first over the lamb so that it would melt a little.

For once, I ate at my work table, surrounded by the jar poems I've been working on. They were lit nicely by the little halogen lamp there, and I placed a little glad of Peat Monster scotch next to the plate (not my favorite peaty Islay scotch, but I've left my Lagavulin with Anne Gorrick and Peter Genovese).

It was a good meal. The pepper on the pears both exacerbated and complemented the sweetness of the pears. The Morbier was good everywhere, but it particularly enhanced the lamb. Not being the best lamb cook, I cooked them only rare, so I would rather have had the chops cooked a bit more, but they were still good. Lamb is a meat sinful in its deliciousness. The greens were sweet in that beet-green way, and the mild golden beets were quite enjoyable. The scotch, every sip of it, was a little jolt, something probably too different from the meal to fit with it, yet I still liked having it.

I'm not sure cooking is art or poetry, but it is creation, and I'm starting to see how it resembles how I create my art, whether through pure writing or these constellations of words and things I'm working on now. We create beauty through accumulation, and it may take a lifetime to accumulate everything you need for a particularly good creation.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 13, 2012 20:31

February 12, 2012

Driftless Radio Poetry

At eleven minutes to 8:00 pm, or eleven minutes to 7:00 pm Central Time, I learned that mIEKAL aND would read on WDRT radio poems from his long career at 7:00 pm Central.

I had almost no time to prepare, but I turned on WDRT's audio stream, retrieved my professional audio recorder, and set the recorder up to record the entire program. When the program was beginning I began to record. I was organized, given the short amount of prep time I had. After about ten seconds, the recorder ran out of space. (I had recorded about an hour's worth of audio only yesterday, and that had, apparently, taken up most of the space on the recorder.)

mIEKAL aND Reads from His Collaborations with Maria Damon (mp3)

With no time to spare, I decided to record a couple of the sections using my phone, rather than try to record the entire program. This would have proved impossible anyone, since with my phone app, I can record in bursts of no more than five minutes. The first part I recorded were mIEKAL's collaborations with Maria Damon, from Literature Nation and eros/ion.

mIEKAL aND Reads Pwoermds He Wrote with Geof Huth (mp3)

The second and last selection I recorded was mIEKAL reading from his and my book of Collaborative pwoermds, texistence. I started a tiny bit late on this and lost a few seconds of the opening, but all of the one-word poems can be hear clearly in this recording.

I wish I had been able to record the entire program (about 35 minutes with mIEKAL aND, but I"m glad I had the chance to collect what I did.

What I heard, though, was mIEKAL challenging a radio audience with types of work they would never otherwise here, and doing it all in his basic Midwestern accent that makes him sound like everyone else, though the last thing he would ever be is like everyone else. He read from his long poem, Samsara Congeries, as well, explaining how he takes the form of another person for each book.

And when he began his section on collaborative work, he explained that he believed in the death of the author, so his work had become focused on collaborations with other writers. And I loved the irony of that statement: the death of the author creates two authors.

We can never truly die.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 12, 2012 19:37