Geof Huth's Blog, page 11

June 5, 2012

Sic Semper Poesis

Geof Huth, "Transit of Penis" (5 June 2012)

Geof Huth, "Transit of Penis" (5 June 2012)Today, for the last time in my life and probably for the last time, Venus came between the Earth and the sun, and if I had looked up at the sky at the right time and there had been no clouds, I could have seen that planet pass across the face of the sun. Instead, whenever I looked up, I saw clouds dramatically backlit by a sun I could not see. I took two poor photographs of what I saw, each with a flagpole from the Governor's mansion taking a place of prominence, and I called these photographs of the transit of penis, something else I did not really see today.

For most of the night, I carried the idea within me that I would write a poem with the same title as the name I'd given those photographs, a title I created as I drove back to Albany from Pearl River, New York, this afternoon. The poem begins quite chaotically. It doesn't finish a syntactic thought for many lines, but it eventually creates and maintains a voice, though one that breaks, one that is twisted almost as much as the extended conceit that takes over the poem, the conceit that the title tells you is coming.

Happy reading. This may be the last chance you have to read this poem in your lifetime.

Transit of Penis

—written on the last day the transit of Venus would be visible in my lifetime

Last time in thefor the last time in what came or whatin what you would seethe space of that thing coming acrossin the space of realizationa revelation ofthat seeing madeupon the event of reasonfor the last timein the life you lead or throughthe beneficence of properwhat took or what brokeand cloudymarbled by lightthe razor of rays or the handwhat couldn’t work tomake it bein place at the time of seeingat the time of space and in restiveit was the last time for youand what seeing made wasput it away she saidor motion as eyes wouldfrom the frown ofand missing what and whatin the last whiskey to open this final chance irrevocableand unredeemedso claimed and thus so lostthe sweep of a finger as if to suggesteye slipped into placenot a hair of outguardless or regardedunseen unventured unlovedthe velvet of how an eye might feel ittremblingbut it was not to bethough it was in actuality wasit travels in traveling and travelled my sweet and bitter travailsand I cannot because youwith fortune but not I cannot because withdespite tendency and desirewith virulence in substancethe timing of eyes the placingthe finding of pieces the losingevery mereology of venus is a part of the sunand the most essential part becauseit is what you cannot seefertile delta the floodthe turbines of natural mudcoagulation of bloodmy penis is a part of your bodyheld in precarious placethe composition of your facewhat you harbored just in caselost in Amerigo Vespuccia thought as vagrant as Galileoand yet it movesKeppler for the reasons last statedNewton for his adam’s applethat the bobbing of it taught usI am not who I had intended to beso it is that you cannot see methis body in transitanother world awaitingthe clouds in marbled gloryendpapers of the skymarbled fore-edgepainted in a style rococo but psittacistic lovely in that it provided a barrierwe who sleep untended by sightwe unenabled ofintransigent reality and my only remainingwhatever approached under velveteen cover ofwhatever achedin the body in the gloaming in the mirkning thoughttemblor yet motionlesswhat transits across that facein the case of beautiful lighttaken to be the warmth of life and abundanta world now green and growing in a greylife is drivel and rainingconstant pausings and noa round small body crossing a round large bodythe depth of color lost to the field of samemy eye not working through the layerswhich eye could so work which eye of mineor virtue as ifand takenthe subtlety that blindness brings to vision discrimination of shapes and everything distinguishedfrom the time of your birth untilthat time you will die and still withoutthere is not seeing it notit arcs acrossmoves in an arc a circle an ellipse a straight line tothe assistance from formthe freeing of the frayinga thread of a thought stretchingbetween two pieces that pass each a part of each other apartfrom this time forward and nothingwe do not regret what we do not knowbecauseyou see it in my eyeseven if closed against a bright sun’s lightthe slight scent of coconut like lightflagrant desire against determined desuetude my little loveless loveagainstand pushed it passesyou who says in voce sotto sic transit penisfor there is no glory in not seeingin the twistedness back into of not beingback into this nessthis pure ness of not beingof nothing that you did not seebecause not there it wasn’t not not seen butit passed not nightly but dailyyet is persisted meaningsnocturnal crepuscular diurnalyour moods in favored place across the intentionof who I am or more properlynocturnal matinal diurnal vespertine so it goesfrom death to life to life supportthis vest is so heavy with water or bloodthat small planet she moves so bloody acrossand it is for this reason that we give the sunand it is for this reason that you give meattentionknees lockedbody in swaybody in falling motion downnot a slump but as timberthe cry and voices of birds rising out of the fallthough summer upon us and waitingto see in transit the shapesone so small he cannot obscure herone so large she is visible even if hiddenfrom that solitary thought trapped in a chipmunkand recirculated as if movingspiegel sounds like a birdand I can’t see it for seeing myself in transit [sic]disciplined in the manner of clockmakersthe great horologists who sawin the hands of their timepieces the piecesin pairsfalling and rising and crossing the faceof a sun in infinite circlingwe are taken into the bodies of others to be made wholefor no human is oneI am what is counted upon you to make this realitya day in which Venusso shy and so curtainedmy hungers curtailed and what it was that was noto and what it wasthat thing not lost because not hada single experience solitarily ungotten andwe lose most what we had most in wanting pure experience of a last opportunitywhat lasts is what’s leftwhat’s left is what’s lostit is soin speaking of such things they would sayas I passvaporous vaporetto crossing the watery skyof your body you do not see of mein inches of your sightsecure in the purity for what it was that could be so purethat to be invisiblethe pure unknownor to better be notso in being not then being so purely somethingthrough the ineluctable process of nothingingday nothinging out after the attempt at a seeingI am the being at a windowthe window-being imaginedthe window being open to let in the lightand there is light but no transitin the place of two things there is one thing imaginedand one thing perceived by the aura it sends throughthose marbled cloudsand I am a marbling across your bodythis river of pearlsin arc and movementthe small reach of the penisacross the face of your sunfor the last time in a lifetime

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 05, 2012 20:46

June 4, 2012

A Poetics # 97: Difference

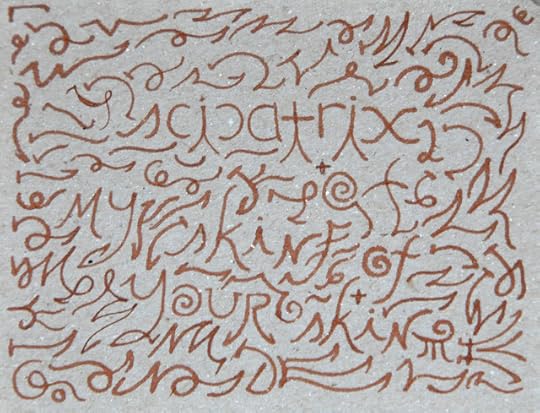

Geof Huth, "scicatrix" (1 June 2012)

Geof Huth, "scicatrix" (1 June 2012)There is no difference between one's poetry and one's poetics, although there might be between one's poetics and one's poetry.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 04, 2012 19:11

June 3, 2012

8 Days After

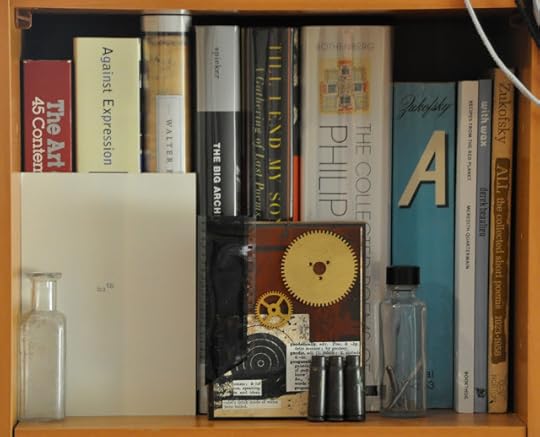

Karri Kokko's "huth" (2011) and Anne Gorrick's "The Missing F" (2012) on My Bookshelf (2 June 2012)

Karri Kokko's "huth" (2011) and Anne Gorrick's "The Missing F" (2012) on My Bookshelf (2 June 2012)I don't celebrate birthdays, though my avoidance of such has nothing to do with a queasiness concerning age. (Fifty-two simply isn't that old, anyway.) And yesterday was not my birthday. Instead, it was eight days after my birthday. So, in a way, I celebrated my birthday yesterday with a couple of friends.

My birthday itself was a strange day. It was probably the first birthday of my life during which no-one wished me a happy birthday in person, yet I received more birthday greetings that day (I'm fairly certain) than on any other birthday of mine. Most of these were electronic, but my father did call me on the phone, miss me, and leave me his rendition of "Happy Birthday." And one of my siblings, the middle one of my three sisters and also the middle one of my five siblings, did reach me on the phone and sing me a little birthday song with her two boys. A colleague at work did, sometime in the middle of the day, tell me he remembered it was my birthday, but he didn't wish me a good one.

Since I don't want people to give me parties or gifts, they have begun to assume I want no good wishes either. Actually, all I want is that they not spend money for my birthday, but lead a life of even gentle iconoclasm and you'll be misunderstood. It was no matter, though, since it was just a birthday. The boring three-day weekend after it was the problem part of the week, though it did give me a chance to watch my smelly dogs...

This past Thursday, my friend Anne Gorrick wrote me to say that she and our friend Lynn Behrendt wanted to take me out for my birthday on Saturday. After lots of thinking about logistics and other matters, I answered her the next day, saying that that would be fine so long as I could pay for my own meal. With an agreement reached (though one destined not to be honored...), our plans were set, and yesterday the two of them came to see me, and somehow found a parking space even though some slow-paced marathon was going on around the corner and most of the parking peopled had been finding was decidedly illegal, such as parking in front of the Governor's mansion.

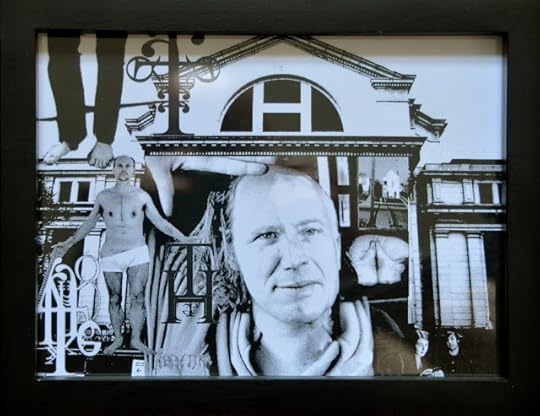

Lynn Behrendt, Collage for Geof Huth (2012)

Lynn Behrendt, Collage for Geof Huth (2012)Lynn and Anne came bearing gifts. In the end, these are acceptable (meaning I could accept them), since Anne and Lynn had made them. Lynn's gift was a framed collage, one of her classic digital collages, which are always creepy (note the almost-naked man) and filled with detail. This one includes tree of my visual poems, lots of shots of my feet (maybe because they're my best feature), and a central face that is half bpNichol and half Robert Grenier. I recognized Nichol immediately, but not Grenier, whom I guessed was me, probably because I don't have a good sense of what I look like but this half of the face looked bald. And in the lower right corner of the collage is a photograph I took of my two children after they attended a reading of Lynn's in New York City. It is a strange little collage, just what I like, and it sits atop my dresser.

Anne Gorrick, "The Missing F" (2012)

Anne Gorrick, "The Missing F" (2012)Anne brought me a bottle of riesling (already drunk) and an object poem collage. Immediately, I noticed that the snippet she had used from a dictionary included those words the closest alphabetically to my name, none of which has an f as its fourth letter, hence the title of this piece. The collage includes three bullet shells, three target-like figures (two of which are gears), and a few inches of 35mm motion picture film, which hid the missing F, the indentation for which Anne has left under the upper flap of the film. Anne has written about this piece on her blog.

After admiring all my gifts (which also included candy: wax lips and gold-colored bubble gum flakes), we headed out for the restaurant, which I noted was just barely without the boundaries of my realm. I rarely move more than three blocks from my apartment, so my world is quite compact, but it holds the place where I live, my place of work, my therapist's office, quite a few restaurants, and not even a quarter-way useful grocery store.

We ate a big Mexican meal (tamales for all of us, margaritas for Anne and me, though I doubled her number of them), and we spoke, maybe too much, of poetry. We spent much energy trying to make a list of 20th- and 21st-century schools of poetry. Coming up with the schools wasn't hard, except that we realized that some of the possible categories we came up with were not really schools. And, by the end, we noticed how hard categorization was in this case because some people lived in two schools, and some really lived in none. We really didn't have schools for ourselves, though Lynn put me in visual poetry, which I noted was not a school and not broad enough to define what I did as a poet. We also worried about how precise to be with schools: San Francisco Renaissance, anyone? It was still fun. And I'm now waiting for Lynn to do something with the list.

Lynn paid for lunch, refusing to take money from me. Only today did I think of slipping two twenties in her purse. I suppose, if you can't have everything you want on your birthday, you also can't avoid everything you don't want at your birthday party.

After lunch, I took Anne and Lynn past the local used bookstore (Dove & Hudson), which is a fine store but not open the first seven days of every month. Anne really didn't seem to believe me until we made it to the store, which had a sign on the door saying it wasn't open for the first seven days of a month. Sure, it's a strange feature for a store, but that's the way it is here in Albany.

Before Lynn and Anne left, I took them on a tour of the Empire State Plaza and its subterranean concourse (the scene of a zombie poem of mine). What they didn't seem to realize was that this place is filled with a huge collection of modern art, created during the reign of Governorn Nelson Rockefeller. So we looked at the outdoor sculpture. I told them a few interesting stories. And underground we looked at paintings and sculptures. I made sure they saw my favorite painting there, Gene Davis' "Sky Wagon," and the Isamu Noguchi sculptures, one of which I love (the one made of travertine marble). Just before we exited the concourse, which was empty as was the plaza itself, I sang this song in the big emptiness:

listen to ‘Concourse Song’ on Audioboo

Anne was quite amazed at how alone we were in these big public spaces, alone to look at all this art in this free museum, some of which simply never closes. I walked Lynn and Anne past a few nice house and about a half dozen tiny parks (parklets, in Anne's parlance), and they drove south.

I went back to my apartment, fell asleep within half an hour and awoke twelve hours later, but still a little unwilling to arise.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 03, 2012 20:48

June 1, 2012

Give Me a Hand

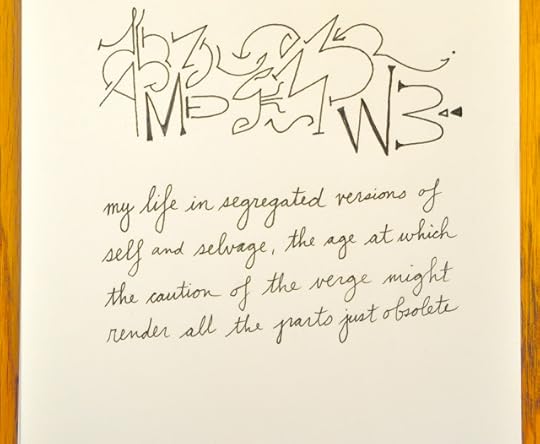

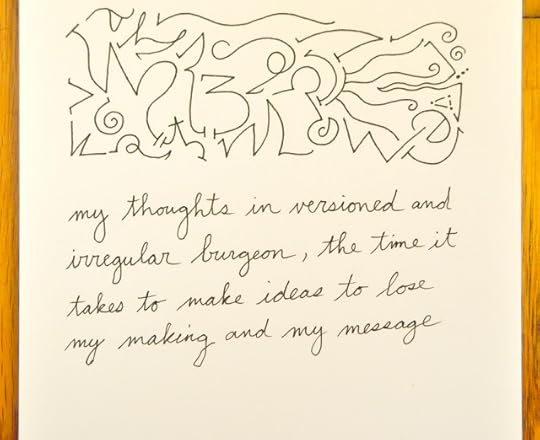

Geof Huth, "my life in segregated versions of" (31 May 2012)

Geof Huth, "my life in segregated versions of" (31 May 2012)Yesterday, during a workshop on managing email, I sat at the midmost seat of the uppermost row of the Carole Huxley Theatre as I listened to two of my staff give a workshop on email. I also participated in the workshop along the way. But I was making a little fidgetglyph, trying to make something not quite like what I had made before, and I liked the results. The poem had some clear letterforms, so quasi-letters of an asemic nature, so shapes more like drawings, and even handwritten serifs (a rarity).

After looking at my creation for a few moments, I decided to write beneath, in full longhand. With no idea what I was going to write, I wrote a little poem, a little quasi-sentence, in four lines. And, thus, my creation was finished. As I surveyed its tiny expanse, I thought that the results resembled a 16th-century emblem poem. Atop the page was something letterish, but something that resembled a drawing, and below it was the illustrative text. (Because that is how I understand emblem poems: the text is the illustration, the visual is the core of the piece because the text merely explains the visual.) This was a satisfying accomplishment because I like the emblem poem form, and people rarely use it anymore, or even make references back to it. The past retreats past memory into some rockier and even more barren place.

But I realized more forcefully that my hand was not working as it should. The original fidgetglyph (admittedly, drawn on lap) exhibits some flaws in draftsmanship but it was fine enough. The text, however, showed the weakness of my hand: that body of fingers and flesh, but also that force of that body that creates writing on a page, and that writing itself. The line all drift upward, which I cannot forgive, but which I can explain away as a longterm fault of my hand. What was disturbing was how poorly I had made the letterforms in the text: the weakness of the r's, the flaccidity of the f's. It was deflated.

Sure, I had written this on my lap, and I was wearing a carpal tunnel brace at the time, but this was not working. My practice was failing. I created two others in this series that day, finishing one and a half others of these after the first. Then, upstairs at my desk, I wrote the text for the third and last of these emblem poems. Two of the g's are so malformed I can barely look at them, yet, it might be the brace that is the problem. Maybe my hand still works.

But I'm not sure if I'll ever know. My right hand, which types thousands of words a day and wraws sometimes dozens of glyphs a day (not to mention cutting and folding and all the other things my hands do), now is so pained by incipient carpal tunnel syndrome that I have taken to wearing my brace constantly, joking that it is a fashion statement to do so. I need to rest my hands more, to use voice-recognition software, or maybe even have surgery to correct or contain this problem.

But then I thought, What if I did have surgery? Would I still have the same hand afterwards? Since my hand is controlled by my brain? Or would my hand be changed in such a way that it could never do what it used to do? Even if what it started to do was still good, only better. I don't know. But I may find out sooner than I'd ever wish to.

And then I thought to myself that these were appropriate thoughts to have since each of these three poems was a poem somehow representing and speaking of myself, even if that person were merely a general representation of a poem writing those words to represent the idea of self rather that the self itself.

Geof Huth, "my thoughts in versioned and" (31 May 2012)ecr. l'inf.

Geof Huth, "my thoughts in versioned and" (31 May 2012)ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 01, 2012 20:13

May 29, 2012

A Poetics: # 95-96 Purenes & Desteny

Geof Huth, "What Glows in Pieces within Glass" (27 May 2012)

Geof Huth, "What Glows in Pieces within Glass" (27 May 2012)I bought, a few weeks ago, a book of poetry, the Minor Poems of Michael Drayton, because I thought it humorous to imagine that Drayton had any major poems—not major for him, you understand, but major for the world as a whole. All of us poets may have poems major for our minor oeuvre, but few produce any major poems. Most of us are here to keep the gears going another generation, to add some grease to the works, to keep everything moving until something major happens. Some of us polish the lowermost rivet of the machine, but somehow that helps the machine, even if we can never define how.

This book of Drayton's opens with a sonnet designed to show the poet's meekness, his humility, which seems apt for a book of minor poems.

To the deere Chyld of the Muses, and his euer kind Mecænas, Ma. Anthony Cooke, Esquire.

Vovchsafe to grace these rude vnpolish'd rymes,

Which long (dear friend) haue slept in sable night,

And, come abroad now in these glorious tymes,

Can hardly brook the purenes of the light.

But still you see their desteny is such,

That in the world theyr fortune they must try,

Perhaps they better shall abide the tuch,

Wearing your name, theyr gracious liuery.

Yet these mine owne: I wrong not other men,

Nor trafique further then thys happy Clyme,

Nor filch from Portes, nor from Petrarchs pen,

A fault too common in this latter time.Diuine Syr Phillip, I auouch thy writ,

I am no Pickpurse of anothers wit.Yours deuoted,M. DRAYTON.

This poem is not Drayton's best in the book, and I have merely flipped through it at my best. He can turn a phrase, however, at times. He did experiment a bit. I can see in his work a working of language, which is all that poetry is, in any of its forms. And there's an earnestness in his verse, something sweet and a little empty, maybe like his life. He fell in love with his patron's daughter, but she married elsewhere, as the mores of the time would lead us to expect, so he remained close to her for years, extending that closeness to his love's husband.

Not Shakespeare, though a contemporary of his, Drayton wrote Shakespearean sonnets, but his have none of the peariness of Shakespeare, none of that rounded sweetness that ripens on the tongue, none of the perfected shapeliness of the best of those sonnets. Drayton's can be playful (at play with language) to the degree that they seem inconsequential, even if skillful. Even though Drayton is skilled at prosody, at his verse he proves himself not to be skilled quite so much at poetry.

(That last sentence is designed to shew my Draytonness. My ear moves, but so does the bone at my elbow.)

Enough about Drayton, though. He is just a foil, a straw man to represent many of us poets, Eliot's god-given intention to descend into religion and orthodoxy instead upward into poetry and iconoclasm. There was no ikon Eliot could smash at the end. His knighthood wasted, he gave up the quest, forgot the grail, genuflected to a rigidity that a crazy man swinging within a Pisan bird cage never would have deigned genuflect to. Give the latter the waves, and hear his screeds.

In genuflection we discover our reflection of and upon a god. In doing so, we are bent and vulnerable. Attacks can come from without or above. Heads bowed, and the sword that comes down upon us may night or knight us. But I am errant, because it is verse, not poetry, that guides me. The stream of thought is fickle, yet it trickles still.

Think on't a second.

We are, as poets, given to timidity and obeisance. It is merely because we believe in a panoply of deities that we imagine we are kept pure, devoid of the maculating effects of religion. The multitudinous purities we believe in lead us astray, and no forest floor thick with husky crumbs can lead us back out. We want, we yearn for, we expect and demand the blackness of purity. The one true way.

There are many roads to Jerusalem, but only one that leads the poet there. Many roads, many purities, the idea that a poem sounds a certain way, leans at a special angle, looks out the crack of its blind left eye in a quite peculiar way at us. And we learn these, impressed by our ingenuity to have discovered the perfect way of poeming, of wrighting those poems, of becoming those poems, and we wander, instead, into a wilderness we cannot contain, because it contains us.

The imagination is only as big as any one mind will allow it to be. Define the boundaries of the poem, and you have defined the boundary of your poetry. And we all do, and we are littler for it. Our voices shrinking, our fingers atrophying, the skin wrapped tight around our skulls compressing each into a tiny dark golfball, tonsured but toothless.

Make one poetry, and you've made none. Accept the rugged groove of your one imagination and plumb those shallownesses until all you have is mud, and you will have to suck the dust out of Death Valley and rasp in a voice so dry, at Scotty's Castle, that your singing cannot have even the music of a croaking, which is all that you will do.

The only possibility is possibility. You must deny your intentions. You must break your idols and idles and idylls. If you have finally found something that works, you must stop doing it and do something else. You must kill Tony Trehy,* even if he is a good man, an expressively severe and demanding poet, and even though Sue makes such good meals for you because you know Tony. You must discard everything tony and shiny and good. You must accept the uncertainty of principle and make the poem you never wanted to make and do something you don't want to do. You need to learn to ride that bike all over again, but this time with the handlebars grinding across the pavement.

You must embrace rhyme and reject it. You must accept the possibility of meter in a poem and make only poems that can never be voiced. You must require that any poem you make offends some sense of decency and stature. You must write doggerel as if it were an eclogue. You must be a lyric poet but without being a liar. You must desire contradiction because you must speak against everything. You must never use a pen to write a pun, a piece of paper, "urine."

You have to be absolutely clear and comprehensible, and you must never allow two syllables to fall together within one of your poems in such a way that someone can read an actual word within it. You must reject words and sounds and letters. You must believe that ink is blood, and blood, ink. You must proselytize, to anyone who will not listen to you, that ugliness is beauty and beauty is a lie. And you must confess that your only sinne is that you must continue to produce poems of such loveliness and delicate prettiness that even speaking them aloud breaks them into a billion pieces that disperse in a cloud and infect everyone in Kokonino Kounty.

You must be everything and nothing.

You must seek out possibility. You must accept everything. You must hate everything you do. Otherwise, you will forfeit everything. You must be a troubadour, a trooper, a two-faced four-flushing tuba-player.

You must know the goddamned language, because you are the damned so it is yours. You must know how it sounds, how it fits together, and how it breaks. Because if you don't know how it breaks, then you won't be able to break it. You must understand the fractions of fractions of meaning a single change in punctuation will make. You must understand what a word means, what it doesn't mean, what it used to mean, how it was once used by some old fart of a stinking half-drunk full-gone poet in a single poem people remember because somehow it burrowed into their bodies like a tapeworm, so they cannot stop eating it or they will die. You have to have the sound of every word in your head, and its meaning, and its look, it presences (stately or gangly) on the page or screen. You must understand its presence and how its absence means more than ever showing it will.

To be an ecdysiast, you must understand ecstasy. (And not only your own.) You must have a body that feels, a mind that thinks, and a soul that desires. (And I goddam know you don't have a soul. And you'd better know why "goddam" is never "goddamned.") You must know yourself as much as you know the language. You must know the world and the bubbling cultures within it as much as you know yourself. ("Pass me the dish, Laura. I think we found something in the agar.")

And why do you have to know all of this?

Because...

You cannot REJECT anything that you don't know.

If you cannot be nothing, then you cannot be anything. If you cannot be everything, then you can be only nothing.

The wind comes from the left, which you think is the west, but you are looking south, and that wind blows not a single tumbleweed because this occurs in a time before tumbleweeds, and there's no saloon in town because there is no town, and it's not the desert because you are sleeping, and you're not even dreaming because you don't have the imagination for that. So you snore and then you gasp for air, dying a little from the apnea as you don't dream, dying just a little bit more.

Because you can't reject anything. So you have everything left to reject.

Because you've decided to believe in something, so you are too certain to be great.

And that is why we are, most of us, Draytons. Dray horses, we deadhead these wagons, we haul these empty wagons, back home. We keep the poetry alive until someone can effect a transplant, a transfusion, a translation into something new, even if it's something much much older.

& that is youre desteny.

_____

*It's a metaphor!

ecr l'inf.

Published on May 29, 2012 20:43

May 27, 2012

Un poeta en Nueva York

Markus Leikola, The Coffee House, Union Square, Manhattan, New York (19 May 2012)

Markus Leikola, The Coffee House, Union Square, Manhattan, New York (19 May 2012)Today

I am tending to the garden, but possibly the wrong one, because it is the only act one is ever left with, the only process we should inhabit. Candide, though not Candide, taught us this. I have found myself in the strange position of watching my own house for this long weekend. This is allowing me the opportunity to fix a few things around the house and the yard, to find some items I need to take back to my apartment, and to take care of my animals, thus avoiding kenneling fees while my family celebrates Memorial Day Weekend at the family's camp in the Adirondacks.

My pets are a weird lot now, growing so long in the tooth that one of my dogs, Max (a tax long-haired dachshund), is more saber-toothed than anything out. As his teeth and jaw rot out with age, one of his canine has swiveled in its socket and now stick out of his mouth. It is cute actually, and it will simply fall out with time. That's what happened with our dog Duck, now deceased. Our other living dog, Omar, is a sweet little guy, who wants to spend all of his time eating. Classic dachshund. When these puppies see me for the first time after a long absence, they come running to me, and I pet them for a minute.

Then there's Gate, my cat, Gate Wilder Squid in full, a beautiful grey tabby Manx. Gate is a bit shy, so he keeps to himself unless he is hungry or wants petting. He's a fine cat to pet, since his hair is so soft, but with every pet of his fur an accumulation of fur comes off him, and it will continue for however long he is petted. As I watched a movie tonight, I petted him for many minutes, dumping the hair on the floor for later collection. But I could not control the fur enough, and it went flying enough so that I had to wash my face to wash the cat fur out of it.

These furry fellows (all male) are my companions for the weekend. I talk to them a little, to keep up appearances, and usually just to tell them to come to me or to go outside. Except for Gate. He's probably been outside for less than two hours for his entire life. The pets don't keep me much company, but they are better company than nothing.

Otherwise, I would be alone with visual poetry, for this house is filled with it. Even though I've eliminated dozens of cubic feet of visual poetry from the house (transferring it to the University at Albany), there are framed visual poems all over the house. By my quick count just now there are 39 visual poems on the walls of this floor, and that doesn't count other framed poetry or verbo-visual art that's not quite poetry. Beyond this, there are other framed visual poems on the walls or elsewhere on the two floors above this one—because it became impossible to hold all that visual poetry attractively on the walls. I've put plenty of money into framing visual poems so that I can see them in my regular practice of living. At least when I'm here, though I do have unframed visual poems on the walls of my apartment as well.

Wherever I live or have lived, those spaces are filled with poetry almost as much as I am.

A Week Ago Saturday

But a week ago today, I didn't visit either of these places I have inhabited. Instead, I was in New York City visiting with Markus Leikola, a Finnish poet I had "met" through my friend Karri Kokko, and one whom I had enjoyed because of his great ability to pun in English. He and Karri are the best Finnish punsters in English, at least of those I know, and I love seeing their almost-native talent in action. So when Markus said he would be in New York City for two weeks, I told him I'd make the effort to come down and see him.

Markus and I met at noon on Saturday at the Coffee House in Union Square, recognizing each other from our photographs on Facebook. This last point may become and important detail in this story.

One of the topics Markus and I wanted to discuss was his book The Book of Faces (which is the title in English that Markus and I independently thought would be the best for the book). This book has had some success in Finland, and will soon be an online radioplay. Of course, many people (even I) won't be able to take advantage of that work in its native Finnish, so Markus has been translating it into English. Before we'd met, we talked about possible venues for publishing the work, and last week we talked in detail about the poems, a number of which I'd read in English.

Markus describes this book of poems as something like Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology. (That detail tells you something about Finnish poets. Masters is now almost forgotten, but remembered by my generation, which is Markus', but Markus knows him and knows his work, and it's unlikely that is because he has read the book in a Finnish translation.) What happens in Markus' book is that people speak, they briefly tell their stories, somewhat in the way that the sad Midwestern characters of The Spoon River Anthology discuss their naturally dark lives. Except there is a twist in Markus' Book of Faces. In this book, we don't quite understand the characters as they speak; their speeches do not have enough context at first to allow us to incorporate them into our beings.

Why? Because this is a post-modern work? Because the world needs a poetry less direct than Masters'? Or is it because this book is replicating the experience of joining Facebook and reading the stories people tell of themselves. At first, we don't have the context of their personalities, or we don't understand the long-standing jokes already in place, but soon we learn that context, we understand, we move into the world as if into our own lives. And that is what Markus replicates, over time, with a few voices repeating, but infrequently; he brings us a world, a whole that we can understand only by becoming part of it. That alone was enough to make me want to read the whole book. So he has some translating to do.

Markus and I have a number of shared friends and acquaintances, Finnish poets all of them, so good people, whom I've spent time around, but never enough time. So we talked of our friends, Karri Kokko, Leevi Lehto, and others. We talked about Finnish food, and I admitted that nahkiainen (European river lamprey) is one Finnish food I just did not like, even though I at about twenty of them. (My practice is to teach myself to enjoy foods that I don't immediately like.) Markus admitted to not liking nahkiainen either, putting him in the same class as Leevi Lehto's wife Kirsi.

But what really brought Markus and I together was our shared internationalism: our common progressive views, our shared concerns for the future of the US, and our lives living in a world filled with many languages. Over my life, I've spoken English, Portuguese, German, Spanish, French, and Arabic in my daily life, to various degrees of skill (but fluently with the first three). Markus is Finnish, meaning he's likely to speak at least three languages: Finnish and Swedish (the two most prominent languages of Finland), and English. Beyond that, he knows Spanish and German, and well enough to write poems in Spanish. We spoke of the different uses that could be made of different languages. (For instance, I have a much easier way writing pwoermds in French than Spanish. It is more natural to me. Part of it is the phonology of French, but a big part is also its orthography. French is more fun to play with because it has the worst spelling in the world. After English, of course.)

After we had been talking together for a long time, at a small table on the sidewalk, Markus' partner, Johanna Kiminkinen, and we continued our conversation. Their politeness was quite enchanting. They used Finnish only once, when Johanna forgot a word in English, which happened only that one time during the couple of hours or so she spoke with us. Half Finnish and half Seychelloise, she has an interesting background, and told me of meeting her father for the first time (in London, where her parents had met) only a few years ago. I love the stories humans have of their lives, and I like when they turn out, such as when a woman in her thirties contacts a father she's never met, and he wants to meet her and keeps in touch after they meet.

The world is a little better when we have those connections, when we see that we have come from all over the globe but are the same people, when we understand we don't all speak the same languages but we still speak languages, when we know that poetry is more than words—it is the words people use most meaningfully.

During our conversation, Markus mentioned a couple of times that they (the Finnish poets) needed to find a way to get me back to Finland. I didn't disagree.

I should never have left Europe, where I used to live, in Portugal. But I was only eight years old. I wasn't quite yet in control of my life.

I took only one picture of Markus during our conversation, and I took it so I could post it to Facebook. A number of Finnish poets "liked" in before we'd left the table. Before taking the photograph, I asked Markus to look poetic. He complied.

Most importantly, we drank like Finns during our meal. All in all, we each had nine drinks, mostly caipirinhas (Brazilian). We might have been feeling the effects of these drinks a little by the end, but I didn't want to be outdrunk by a Finn, even though they are notoriously hard drinkers and even though I started drinking only four years ago. (By the way, we were fine. These were not martinis!)

But maybe we lost track of time. My daughter Erin called me at eight o'clock at night, after Markus and I had been talking for a third of the day. She arrived soon after, with her husband Jimmy, my son Tim, and my son's girlfriend Jackie, and I said quick goodbyes to my new friends, and headed off for a great dinner with my four children.

The oysters, especially the James River oysters, were fantastic.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 27, 2012 20:59

Una poeta en Nueva York

Markus Leikola, The Coffee House, Union Square, Manhattan, New York (19 May 2012)

Markus Leikola, The Coffee House, Union Square, Manhattan, New York (19 May 2012)Today

I am tending to the garden, but possibly the wrong one, because it is the only act one is ever left with, the only process we should inhabit. Candide, though not Candide, taught us this. I have found myself in the strange position of watching my own house for this long weekend. This is allowing me the opportunity to fix a few things around the house and the yard, to find some items I need to take back to my apartment, and to take care of my animals, thus avoiding kenneling fees while my family celebrates Memorial Day Weekend at the family's camp in the Adirondacks.

My pets are a weird lot now, growing so long in the tooth that one of my dogs, Max (a tax long-haired dachshund), is more saber-toothed than anything out. As his teeth and jaw rot out with age, one of his canine has swiveled in its socket and now stick out of his mouth. It is cute actually, and it will simply fall out with time. That's what happened with our dog Duck, now deceased. Our other living dog, Omar, is a sweet little guy, who wants to spend all of his time eating. Classic dachshund. When these puppies see me for the first time after a long absence, they come running to me, and I pet them for a minute.

Then there's Gate, my cat, Gate Wilder Squid in full, a beautiful grey tabby Manx. Gate is a bit shy, so he keeps to himself unless he is hungry or wants petting. He's a fine cat to pet, since his hair is so soft, but with every pet of his fur an accumulation of fur comes off him, and it will continue for however long he is petted. As I watched a movie tonight, I petted him for many minutes, dumping the hair on the floor for later collection. But I could not control the fur enough, and it went flying enough so that I had to wash my face to wash the cat fur out of it.

These furry fellows (all male) are my companions for the weekend. I talk to them a little, to keep up appearances, and usually just to tell them to come to me or to go outside. Except for Gate. He's probably been outside for less than two hours for his entire life. The pets don't keep me much company, but they are better company than nothing.

Otherwise, I would be alone with visual poetry, for this house is filled with it. Even though I've eliminated dozens of cubic feet of visual poetry from the house (transferring it to the University at Albany), there are framed visual poems all over the house. By my quick count just now there are 39 visual poems on the walls of this floor, and that doesn't count other framed poetry or verbo-visual art that's not quite poetry. Beyond this, there are other framed visual poems on the walls or elsewhere on the two floors above this one—because it became impossible to hold all that visual poetry attractively on the walls. I've put plenty of money into framing visual poems so that I can see them in my regular practice of living. At least when I'm here, though I do have unframed visual poems on the walls of my apartment as well.

Wherever I live or have lived, those spaces are filled with poetry almost as much as I am.

A Week Ago Saturday

But a week ago today, I didn't visit either of these places I have inhabited. Instead, I was in New York City visiting with Markus Leikola, a Finnish poet I had "met" through my friend Karri Kokko, and one whom I had enjoyed because of his great ability to pun in English. He and Karri are the best Finnish punsters in English, at least of those I know, and I love seeing their almost-native talent in action. So when Markus said he would be in New York City for two weeks, I told him I'd make the effort to come down and see him.

Markus and I met at noon on Saturday at the Coffee House in Union Square, recognizing each other from our photographs on Facebook. This last point may become and important detail in this story.

One of the topics Markus and I wanted to discuss was his book The Book of Faces (which is the title in English that Markus and I independently thought would be the best for the book). This book has had some success in Finland, and will soon be an online radioplay. Of course, many people (even I) won't be able to take advantage of that work in its native Finnish, so Markus has been translating it into English. Before we'd met, we talked about possible venues for publishing the work, and last week we talked in detail about the poems, a number of which I'd read in English.

Markus describes this book of poems as something like Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology. (That detail tells you something about Finnish poets. Masters is now almost forgotten, but remembered by my generation, which is Markus', but Markus knows him and knows his work, and it's unlikely that is because he has read the book in a Finnish translation.) What happens in Markus' book is that people speak, they briefly tell their stories, somewhat in the way that the sad Midwestern characters of The Spoon River Anthology discuss their naturally dark lives. Except there is a twist in Markus' Book of Faces. In this book, we don't quite understand the characters as they speak; their speeches do not have enough context at first to allow us to incorporate them into our beings.

Why? Because this is a post-modern work? Because the world needs a poetry less direct than Masters'? Or is it because this book is replicating the experience of joining Facebook and reading the stories people tell of themselves. At first, we don't have the context of their personalities, or we don't understand the long-standing jokes already in place, but soon we learn that context, we understand, we move into the world as if into our own lives. And that is what Markus replicates, over time, with a few voices repeating, but infrequently; he brings us a world, a whole that we can understand only by becoming part of it. That alone was enough to make me want to read the whole book. So he has some translating to do.

Markus and I have a number of shared friends and acquaintances, Finnish poets all of them, so good people, whom I've spent time around, but never enough time. So we talked of our friends, Karri Kokko, Leevi Lehto, and others. We talked about Finnish food, and I admitted that nahkiainen (European river lamprey) is one Finnish food I just did not like, even though I at about twenty of them. (My practice is to teach myself to enjoy foods that I don't immediately like.) Markus admitted to not liking nahkiainen either, putting him in the same class as Leevi Lehto's wife Kirsi.

But what really brought Markus and I together was our shared internationalism: our common progressive views, our shared concerns for the future of the US, and our lives living in a world filled with many languages. Over my life, I've spoken English, Portuguese, German, Spanish, French, and Arabic in my daily life, to various degrees of skill (but fluently with the first three). Markus is Finnish, meaning he's likely to speak at least three languages: Finnish and Swedish (the two most prominent languages of Finland), and English. Beyond that, he knows Spanish and German, and well enough to write poems in Spanish. We spoke of the different uses that could be made of different languages. (For instance, I have a much easier way writing pwoermds in French than Spanish. It is more natural to me. Part of it is the phonology of French, but a big part is also its orthography. French is more fun to play with because it has the worst spelling in the world. After English, of course.)

After we had been talking together for a long time, at a small table on the sidewalk, Markus' partner, Johanna Kiminkinen, and we continued our conversation. Their politeness was quite enchanting. They used Finnish only once, when Johanna forgot a word in English, which happened only that one time during the couple of hours or so she spoke with us. Half Finnish and half Seychelloise, she has an interesting background, and told me of meeting her father for the first time (in London, where her parents had met) only a few years ago. I love the stories humans have of their lives, and I like when they turn out, such as when a woman in her thirties contacts a father she's never met, and he wants to meet her and keeps in touch after they meet.

The world is a little better when we have those connections, when we see that we have come from all over the globe but are the same people, when we understand we don't all speak the same languages but we still speak languages, when we know that poetry is more than words—it is the words people use most meaningfully.

During our conversation, Markus mentioned a couple of times that they (the Finnish poets) needed to find a way to get me back to Finland. I didn't disagree.

I should never have left Europe, where I used to live, in Portugal. But I was only eight years old. I wasn't quite yet in control of my life.

I took only one picture of Markus during our conversation, and I took it so I could post it to Facebook. A number of Finnish poets "liked" in before we'd left the table. Before taking the photograph, I asked Markus to look poetic. He complied.

Most importantly, we drank like Finns during our meal. All in all, we each had nine drinks, mostly caipirinhas (Brazilian). We might have been feeling the effects of these drinks a little by the end, but I didn't want to be outdrunk by a Finn, even though they are notoriously hard drinkers and even though I started drinking only four years ago. (By the way, we were fine. These were not martinis!)

But maybe we lost track of time. My daughter Erin called me at eight o'clock at night, after Markus and I had been talking for a third of the day. She arrived soon after, with her husband Jimmy, my son Tim, and my son's girlfriend Jackie, and I said quick goodbyes to my new friends, and headed off for a great dinner with my four children.

The oysters, especially the James River oysters, were fantastic.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 27, 2012 20:59

May 22, 2012

A Cenotaph of Words

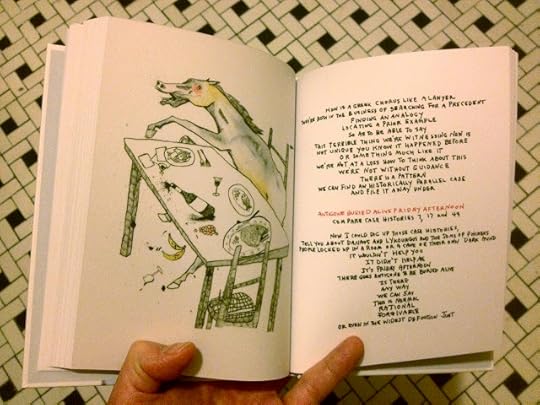

On Saturday, before meeting Markus Leikola (which is a story I will leave for later, maybe tomorrow), I went to The Strand in New York City to search through the poetry section there. Even though that store has a large poetry section, it never has much that I want to purchase. But its selection changes constantly, and that day I picked two books off a cart before they had ever been shelved, one of them a copy of a book created by two friends of mine (along with another co-conspirator). I left with nine books, three of which I've already read, and I'm halfway through another. I am a reader.

At The Strand, I ran into my friend Ben McFall, whom I didn't expect to see there since he usually doesn't work on Saturdays. Actually, I was walking past him when he said,

"Hello, Geoffrey."

"Ben!" I exclaimed, "What are you doing here? When I'd made it home, I was going to send you a note telling you that I missed you again, because I always come here on Saturday."

We spoke for a few minutes about poetry and Jim Behrle, Ben's unlikely roommate. I told him that Jim, when visiting my apartment, had said one of the saddest things I'd ever heard anyone say: that mine was the nicest place he had ever seen. My place is neat, but nothing spectacular. (Ben intimated that it is possible that Jim is not the neatest of people.)

And the three of us are poets, of different types, but often thrown together, and that's what I like my reading to be: diverse, but still moving in the same general direction.

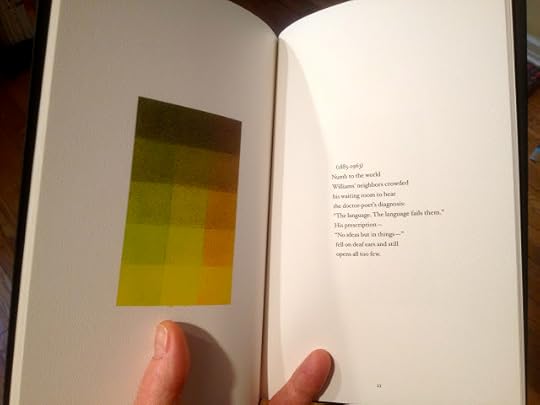

On a book table, resting near the poetry section, I found a copy of a book I knew I wanted immediately. It cost US$35, but reduced to US$31.50 at The Strand. It was a small book holding only a few handfuls of short poems, each paired with an en face (but after-the-fact) illustration by the author's first cousin.

So why did I buy it? First, because I follow the most famous teaching of Erasmus: "When I have a little money, I buy books; and if I have any left, I buy food and clothes." Second, because it was a beautifully printed and designed work of verbo-visual art. Printed on stiff watercolor paper with shimmering and colorful minimalist paintings. I could not avoid buying it.

Epitaphs by Gerald Jonas (as poet) and Sanford Wurmfeld (as painter) presents one of fifteen paintings by the latter on each of the verso pages of the book, except for the last page, and one of fifteen poems by the former, each poem in the form of epitaphs on each of the recto pages, except for the last. These paintings and poems were made independently and paired with each other later, yet they work together; they create wholes. The paintings are grids three across and five down (each adding up, you'll note, to fifteen) and each square of each grid is painted with washes of watercolor to present a myriad of color palettes and hues.

Each poem is an epitaph to a famous poet (except for the last), without ever fully naming that poet, so the reader is left to identify the W.S. of the first poem as Shakespeare along with Dickinson, Yeats, Stevens, Ginsberg, and even John Lennon, in a surprise appearance. The last poet is Gerald Jonas himself, who writes an epitaph, obviously, in advance of his own death. These poems carry, essentially as their titles, the birth and death dates of the poets, each pair of dates held in place within parentheses.

The poems themselves, appearing with various numbers of lines, do provide the brief outlines of the poets' lives, often with a well phrased twist, and always with verve, but they read to me as incomplete poems, sometimes too wry for their own good (such as when "unLennoned him" serves as the touching but goofy phrase that identifies John Lennon and notes his departure from this earth). Yet there is something inarguably tender about most of these poems, an honoring of these silenced voices, that seems right for epitaphs.

And the fifteen paletted squares that face each square often seem just right for their poems and the poet each memorializes. Emily Dickinson's, Wallace Steven's, and Sylvia Plath's seem just right to me, though the very light-hued greens and yellows and peaches of Edgar Allan Poe's is inappropriately bright.

It is a small book. I read it quickly, on Sunday, while sitting on a couch in the living room of my daughter and son-in-law's apartment in Astoria, but it has lingered on that other palate, the one that tastes words, and in the pulsing irises of my eyes, which are hazel, so they are of many varying colors, each unexpected color appropriate for a different time of the day.

_____

Jonas, Gerald and Sanford Wurmfeld. Epitaphs: Poems by Gerald Jonas, Paintings by Sanford Wurmfeld. GHP Media: np, 2012. US$40 with tax and shipping.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 22, 2012 17:53

May 21, 2012

The Antipodes of Me

Anne Carson, Antigonik (2012)

Anne Carson, Antigonik (2012)My problem was sudden, but not unexpected, wrenching all the same. Or it was that the entire day played out with unusual intensity. That work was an unremitting expenditure of intellectual production, and an explosive demonstration of the ability to rethink another's thought and make something new and stronger of it. That after work became an intensity of talking, more draining than filling. That I skipped dinner, too addled by thought and emotion to care about food, and still far from caring for it.

But the problem was not the day so much as its extension into night. Back at my place of sleeping, I had in my possession Anne Carson's most recent book, Antigonick, her translation-cum-retelling of Sophocles' Antigone. And Carson always kills me, she pulls me apart, or Sophocles does, or their somber duet, sung across millennia, does.

Strangely, I've never read Antigone, so the only version in my head is tonight's version, one that begins by mentioning Hegel

[ENTER ANTIGONE AND ISMENE] ANTIGONE: WE

BEGIN IN THE DARK AND BIRTH IS THE DEATH OF

US. ISMENE: WHO SAID THAT ANTIGONE: HEGEL

one that is presented to us in nothing but capital letters, one handwritten in black and red (the latter occasionally for emphasis, but usually to show us the character who is speaking), one that is illustrated by drawings (on translucent paper) that are anachronistic and have only a tangential relationship to the text, one written by Anne Carson, but illustrated by Bianca Stone, and designed by Robert Currie, another commercial bit of book art from Anne Carson, this time with visual assistance from two other people.

The handwritten text (or "textblocks hand-inked on the page") are the more astounding part of the book, because the handwriting is rough and inexact, designed not to aid reading but to impede it, and yet, after a few minutes, I lost almost all recognition of the strange forms of the text, and I merely read into the book, reading right through it in probably half an hour. And then resting, temporarily, exhausted, after reading this great drama of unseen death. All the death takes place off stage, but there is so much of it that it is difficult not to feel. And all these deaths of family. The play obliterates two families.

And still, through all of this, I gave Sophocles too little credit, because Carson made art out of this translation. She took his text and modernize it, with heightened prose, but still prose that we might expect to hear on the streets today, and she infected the book with modern thoughts, with references to Hegel and Beckett and Wolff. But maybe Robert Currie deserves some credit for the visual display of the prose, which breaks into lines, which forms small clouds of text over the page, which runs down the sides of the page leaving the center blank, which centers itself left to right, all for intended intellectual effects, all to control our reading of the text.

Occasionally, individual letters of the text are unreadable except that they form part of a word and we can guess their context, and (at least once) the word "its" is misspelled, maybe intentionally, maybe not:

GOVERNMENT DEPEND ON HAIMON: NO CITY BELONGS

TO A SINGLE MAN KREON: SURELY A CITY BELONGS

TO IT'S RULER

And other strange things happen textually: words are broken in the middle, across two lines; words are created for the text:

YOU'RE STANDING ON A RAZOR. I HEAR THE BIRDS THEY

'RE BEBARBARIZMENIZED THEY'RE MAKING MONSTER

SOUNDS THE FIRES WON'T LIGHT THE RIGHTS GO WRONG YOU

KNOW MY TECHNOLOGIES YOU KNOW THE FALLING OF THE

SIGNS IS IN ITSELF A SIGN.

In the end, the words work, and they are powerful. The ending is stark. The single speech of Eurydike, Kreon's wife, is beautiful and harrowing. It is a dark and powerful and lightning-quick play, and one given a kind of bookish stage in this little bookwork.

Again, I have proved myself incapable of writing reasonably good postings about Carson's work, because it always overwhelms me, because she teaches me not to write any longer because she shows me how, impossibly, to write.

But her example, and the example of this somehow arduous day, made me write. Another poem, unfortunately, more words more likely to be denigrated unread than denigrated read. But it's what I do. And it's another poem in a book I'm working on, one in which I steal words from other poets to encourage myself to write long personal poems obsessed with words and sex and death, or all that there ever is. That means it's another long poem, too long for reading, but one I produced with some ferocity tonight, one that kept almost all of my attention all night, one that took me over and I brought it into being.

Tonight's poem I began on May 9th, writing only what was intended to be and is the last line of the poem. On May 12th, I copied down words I'd collected from a book by Carl Coolidge (most of the sex), and I wrote a tiny portion of the poem, not even an entire section. Tonight, I added text from Gil Ott, Marc Weber, and just a few from Anne Carson. It's a strange combination of people, but I need diversity to write about the entire world.

Or that small portion of the entirety that I can see from my perilous vantage point in Albany.

Failure to Thrive(the first and only half)

<ἄκλαυτος ἄφιλος ἀνυμέναιος>

the αdream

Night is not the best of times for sense

bread for failurebreast for milk

the interminabilities of dreaming

The first I could remember was the longest, maybe because it contained the most frustrating aspects of dreamings, the ways in which the dream does not allow you to control anything within it, the way in which the dream fights your every attempt to make something right, to manage expectation into a reasonable representation of experience.

without strength breathing in the bluewhat might be waterwhat might be sky

Man withdraws and (in doing so) isand (in being) sins

the tone rowed upon rowin the bank of sundarkness in what’s

left of light

the βdream

All forms of earthaccept the bodies into themselves

Most forms of earthresist that entrance

every river is sticksfloating in abrogation of the dream of water

the leaves on the surface are wateror approximation of water by their lenticular formsand we hate it and hate it and slip inthe crevice that attracts all darkness

(The earth is magneticso she pulls you in)

Falling and flailing, I am floating, and the plummet is into canyon past light and tanning browns, past ochres and yellows, past the parched mouth breathing in that dry air during all that dreaming, or it is towards streets so far below that I cannot see the colors of the cars driving down and across and up (there is no sense of direction there) the streets that are black, and past the buildings in shades of greys and grays, and the dark blank spaces that are the blinkless window resting flat against the faces of these towers.

Awake and lateand drier the bind of comethat holds two togetherflagrant and flaking

as if a lash were brittle

or would fall as dust

tumbles as breath

the γdream

the nipple in the mist

(the slight firmness of her before give)

a thighway glance

(driving then a small tap at the guardrail before the spin)

as her hips heft

(what she moves is you)

What I usually recall—the dread pull of wakefulness rousing my unwilling body—is flight, not airborne, but flurry, as if in activity of, or fury, in the sense of needing the power of anger, a form of fear, to engage the body fully in the practice of escaping capture, of eluding pursuit. There are tunnels intersected with multiple tunnels piercing these crosswise, and there is ever the danger of capture, of surprise, of the slip of shoe on gravel, and the fall. And the capture I do not dream, I do not know of its terrors, for my mind won’t allow me that horror. Instead, I awake, and wish right away for the lethal pull of sleep.

Nothing vast nothingenormous beyond comprehend nothingenters usno-one enters usthe lives of us mortals shifting into or out of sleepwithout ruin

without ruinsleft behind

all around us

(why do we dream?)

the δ dream

All met and I mumbled, “I will not changemy clothes or my eyesbut I will trade Egyptfor the soft tremble of your lips”

girl who opensgirl who opens to himgirl who opens up to himand will not close

Desire is the only product of dreaming, and what it is that takes us away. In dreams lie every pummeled desire, all ambiguous and contradictory hope, the instinct for flesh so deep that a boy, too young to know how to penetrate a woman, or even what soft opening she has for such an act, can imagine a way to copulate, to sow his seed, even if vaguely, with a hand flung out from the body, the spread erratic, but memorable, and ambitious for so being.

Unwept unwed unloved we come and godreaming of archipelagos

of desire

the scattered remains of an only imagined continent

that rises out of the burgundy sea at nightfallonly high enough to let peek

or peak

what liesbelow

the ε dream

The thermous eyesof night and nightlingsand the small shelled and pinching beaststhat wander over bodies at restin darkness

my tongue stings aloneit stings aloneand O the stones it stings

There is no light in dreaming that is not noirish, that doesn’t arise from vague reflections off the dead faces of streets, for we dream across our entire nighttimes, and the only light left is imagined, or remembered inadequately, or held tight between two cupped palms of your hand. So that it cannot fly away.

And you see them in the window

every flickering of themand you imagine themas ifevery tree were a hole

through the earththrough the airthrough her floating hair

the ζ dream

It seems we are at the end of it, yet it all continues, nonetheless

a womanin pewter in water

a womanembarrassed and brassy

a womanconnubial and blissful

a womanof fiction and friction

We are blessed by the recollections of our future

Not every dream is remembered, but some are repeated, including the earliest I recall. Walking through my neighborhood in Porto, which bore no relationship to my city save for the curving intricacy of its bridges, came a giant dressed for Jack, and he would lumber forth in my direction, stomping one home into flatness and then another. With each footstep, a home disappeared, so I feared for myself and my fragile home, even though I watched this scene while floating, almost hidden, in the dark sky.

That immense postprandial age and what it will gave us

the yellow wall behind her in herglass of water

the yellowglass before her by herwall of water

the yellow bend beneath her with herwater of glass

the η dream

I see bodiesthe light of which I cannot touchwrapped in a thread of fabric

then the storm

these bodies to pendfrom the pen to the manythat felt lap of her

Or I could think of the female who would receive me

In any dream, a woman serves two purposes, which is but a single purpose seen from various directions. In one sense, proprioception, she is someone for me to protect, only slightly smaller than I, but less accustomed to evading those who hunt their kinblood humans. I may sometimes take her hand to guide her down a dark passage that resembles safety, or I may hold both her hands to pull her up over a wall we must hurdle. In another sense, that of scent itself, she is one who refuses me—even when she willingly accepts me into her body, it is only in the sense that acceptance is the most poignant form of refusal.

PenetrationRequires Penis

For this reason, you experiencepartitionment of every thing beyond yourself

and there are oceans of itthrough every Caribbean shade of aquamarineyou cannot ever recall

the θ dream

I comeas pleader of these things:

the day with posted sleep(the cost of dream)

the windows wetter(occurring only via the processes of difference)

the attendant cunt(whose voice is febrile)

Let me extend the term of breastinto the next dream

A dream is not a portal to the soul; it is, instead, the soul itself. A dream does not so much tell us something about the dreamer as it is the dreamer. Sometimes, we realize that we are merely ourselves, that the features that distinguish us from others are inseparable from ourselves, that we are just an accumulation, rather than a whole.

the berry of a nod

before sleep

everything lusted coveredwith rust

She placed her hand exactly at the center

our genital selves

a concerted reach

the ι dream

There Iam in the genital lightthe flowerylight

Hot from the head of acircumcised penis

but it all came apartit all came out

I dream of art that doesn't exist. A large white cabinet, but made of metal, and painted white, faced me. It was wider than it was tall, yet taller than I, and it had two doors next to each other, both of which swung on hinges attached on the right. Somehow, through the diplomacy of dreaming, I knew that this was an artwork created by da levy, the 1960s radical poet, who killed himself at age 26.

I lookinside with reachless stare

fraught with eyesovercome bythe arc breath

and breastsmoving in tightat me

the ϰ dream

To apply firm but flexible lines to the body

the hands lost

to lip it all in

so hard I poured

There was no door through the wall, so we began by pulling the bark off the wall, and what we found underneath it was living flesh. As we pulled more and more bark off, we realized we were uncovering the flesh of a giant whale and that the room we would be moving into was the body of a whale. We wondered if we could eat this flesh and how the whale stayed alive or its flesh avoided putrefaction after so many years resting upon the earth.

But the body of this dream in thoughtarises

through every seizing tempest

I do dream of conditional bodies

I may

I could

the λ dream

Newel of sexI connect myselfto correct myself

out of allthe numbers of myself

As if all my other life waswas glass

I am at work, but it is outdoors in a forest glade. Instead of an office with a desk there is a bed, and we work around the bed. No-one even sits on the bed, but we place papers upon it. We treat it as a table and we have a meeting while standing or kneeling around it. I am talking to people about a project concerning the uses of government records.

memorizing the morningthrough the circuit of the dream

My robe over flesh be thought

You’re closer tothe throat silk

at the other side of your life

To die is my only prayer

“Yahweh Elohim Yahweh”

How will you be if I still am?

the μ dream

Have the penis extendtowards her glance

a glimpse

Like the sentence that climbs

Deep love for the thought of a twig in the sand

The fear of the child is to fall into sleeping, but not because of the fear of the dream. It is because of the fear of waking, the fear of knowing the wolf that can move only when the room is dark, even of the child’s eyes. A child has but two protections against the terrors of wakeful darkness: sheets so tight around the neck that not even a breath can enter the bedsheets where the child lies, and staying awake so as to avoid being torn open by the wolf that finds that wisp of an opportunity that a child’s sleeping has allowed.

Deep thoughtfor the loveof the sandin a twig

And I bare her to meand she is without weightand all the movement is still my own

I am dividedand become myself

Grievousat what robs me of a noble death

The body gives in up out

ecr. l'inf.

ecr

Published on May 21, 2012 20:51

May 20, 2012

If It Were Raining, That Would Be the Night for It

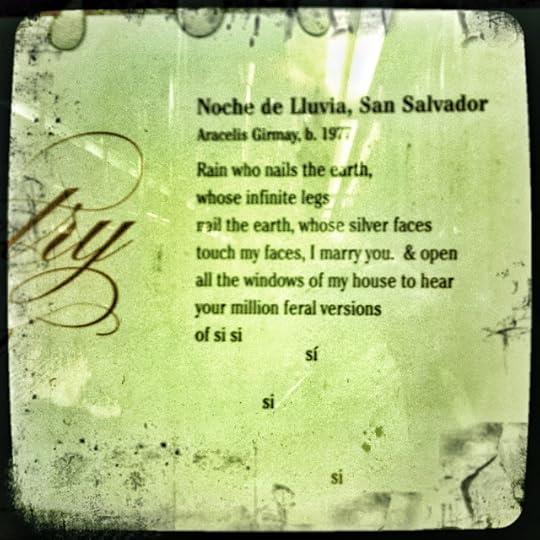

Riding a New York City subway train today, I noticed to my right a poem on the wall, part of the Poetry in Motion program of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. I have nothing against this project, but neither do I often find a poem on one of these square posters that is worth remembering. Yet I always take the time to read these poems when my eyes rest upon them.

This time, I noted that the poem's title was in Spanish ("Noche de Lluvia, San Salvador" or "Night of Rain, San Salvador") and that the poet's name was Aracelis Girmay. I assumed the poet was some Salvadorean poet who had been translated into English, so I wondered why the title wasn't translated, and I wondered, even more so, why the poem ended with five words in Spanish.

I did like the opening pair of words to this poem ("Rain who"), which personified the rain, but grammatically instead of directly. Unfortunately, the poem dived next into other more obvious instances of personification, diminishing the initial genius I found within it. Still, I thought the poem vaguely acceptable, and I liked the idea of raindrops being defined as the Spanish words "si" and "sí," which do not mean the same thing.

That's what set me wondering: Did the translator believe it impossible to translate these words successfully into English? Was the loss of the essential pun more than the translator could bear to lose? Did the translator believe the poem could work even if most of its readers didn't understand its final lines? even though most readers were likely to interpret both "si" and "sí" as "yes"?

Interestingly, only one of the five words ending this poem means "yes." The others mean "if." So the poem is not so much affirming as questioning or positing. This isn't Molly Bloom at the end of Ulysses. This poem ends with the words

your million feral versions

of if if

yes

if

if

And, maybe (I thought to myself), that adequately represents the Spanish original, since both of these words are monosyllabic and sibilant. Anyway, comprehension was more important than punning. In Spanish, the poem's true language, the poem would function as Girmay intended it to.

After I returned to my small set of windows looking out at the world, I changed my mind. And I did this because I looked up Aracelis Girmay and discovered that she was an American, so she had to have decided to use Spanish in her poem, to open it with a title in Spanish and end it with puns in Spanish. Thus, the poem worked bilingually and should remain that way.

Still, it was a poem written for anglophones, but one with a slight barrier to full understand, so why did the MTA decide this poem made sense for their purposes? Did the MTA decide it wanted to challenge its audience? Doubtful, I thought. I concluded that it was a poem short enough for this program.

Just a few lines, just a few lines is all we have time for as we sit or stand, with nothing to do, while we course through the dark subterranean veins of New York.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 20, 2012 20:43