Geof Huth's Blog, page 10

September 16, 2012

Tell Them that You are the Descendant of Forty-Niners, that Your Ancestors Have Already Crossed the Continent (and Some Went around the Continent below Us) to Get to that West-Facing Coast

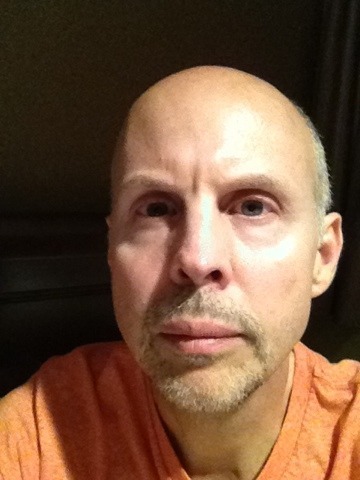

Erin and Jimmy Long Just before They Leave on a Roadtrip to Los Angeles (Schenectady, New York, 9 September 2012)

Erin and Jimmy Long Just before They Leave on a Roadtrip to Los Angeles (Schenectady, New York, 9 September 2012)Last Saturday, not yesterday but eight days ago, I was working in the yard and in the alley that is but an extension of the backyard, and I was worrying about climate change.

"Worrying" is the wrong word, but I can think of nothing better. What I felt was something like the worst kind of dread, the dread you feel when you know something is happening. The dread of knowing what one's life actually was, the dread of not just oncoming, but imminent, death.

Yet my dread was subdued, held in place by subconscious will, by medication, by the fact that I was working almost constantly.

You see, the next day, my one and only daughter Erin and her husband would begin a weeklong trek across this continent, having left their apartment near the mouth of an ocean-feeding river that runs through New York City so that they could make it to the opposing ocean, the rough Pacific, the ocean of my own birth.

And, maybe, even if one's only daughter is twenty-eight years old, a father mourns, in some quiet way that doesn't show on his face, the movement of his daughter a continent's width away from him. And, maybe, that mourning was part of my dread, though I didn't hear that in my mind on Saturday, on that day before the Sunday they left us.

Each of us always has many reasons for dread. We just need to look at the reasons to see what we have in stock. On that Saturday, we were awaiting the possibility of tornadoes driving past us. New York sometimes does experience tornadoes, but their appearance is a rarity. We don't live in a world where we think of tornadoes. So the thought of the possibility of a tornado running through our city seemed, a tornado spun off, maybe, from the swirling of hurricanes hundreds and hundreds of miles away, seemed a sign. At some point, the earth will be off balance, the weight of the heat we humans create on this small speck of dirt and rock will finally throw the weather into something we won't recognize, weather that raises the level of the sea, that pushes the tropics both north and south, that creates huge droughts, monstrous hurricanes, and bizarre meteorological events.

So it was that I was lying on a couch, sleeping, too tired to continue to work. So it was that I was dreaming and probably gasping for air as my sleep apnea took hold of me as it does every night. So it was that I was awoken by the sound of wind through the window. I awoke suddenly to a sight not from the Northeast but one from Middle Tennessee: The trees outside the window were blowing wildly, rain coming down. I rushed to close all the open windows, but what I thought as I did this was that I was watching the movement north of the thunderstorms of Tennessee, maybe only because they were a bit ahead of a tornado itself, but also maybe because the weather all around me was changing in a wild way.

If you have experienced a thunderstorm only in the Northeast of the United States, if you have never experienced a thunderstorm from Tennessee, you have never seen a thunderstorm. Such storms are common in the summer in Middle Tennessee, and many late afternoons end with violent storms, often quite short but some lengthy, that are filled with darkness, with winds powerful enough to shake every tree, with rain that makes it impossible for you to drive through it because you can see nothing beyond your windshield. This was the storm that I thought we were about to have in Schenectady, on that past Saturday.

But it passed quickly. In less than a minute, the storm withdrew to the meekness of a Northeastern storm. And no tornado arrived. I pulled weeds out of the yard. I dug two six-foot-tall mulberries out of the raspberry patch. I pulled the multitudinous weeds out of the brick walkway in the front and the brick patio in the back. I pulled the dried stalks of the daylilies out of their beds in the alley, and I pulled wolfing vines and other thick weeds out of the farthest reach of our alley.

Even there, though, the climate seemed to be changing. What used to be our thickest bed of daylilies had finalized its transformation this year into nothing but tall grass. From this year on, the process for controlling this patch of land will be nothing more sophisticated than mowing. Something has happened to this westernmost bed of ours. Maybe all it is is pollution slipping off the parking lot hidden behind a giant stockade fence. Maybe the light of the sun is too dull or too bright at that spot. No matter the reason, the daylilies are gone.

Still, plants thrive there, better than humans. Everything turned a weed, life continues. Even the rose of Sharon bushes I planted against that wall-like fence almost two decades ago continue, no matter what vines wrap through their branches. And at the spots where I sawed off limbs so that cars could pass undisturbed past these tall bushes, the roses of Sharon were spitting out nosegays of short branches filled with green leaves. Something like vibrant life.

Even as the daylilies were dying on one side of the road, the world was alive everywhere else.

My job that weekend was cleaning. I cleaned the yard of weeds. I cleaned the house of evidence of its former inhabitants. I took items of mine out of the house. And on the day Erin left, I spent most of the day cleaning her room, throwing away garbage (most not hers) I uncovered in her closet, consolidating the few possessions she'd left behind, and neatening and cleaning the entire room. It is a skill of mine. I've moved something like 48 times in my life, nearly one move for every year of mine on earth, so I know how to abandon treasured possessions, how to identify what to keep, how to travel light into the next world.

So it was that my daughter traveled into her next world, one that faces Asia instead of Europe, one that falls asleep three hours after my world does. The loss that this change brought to those of us left on the right side of the continent is what convinced me to write what I'm writing now. In some way (vague and indistinct) what I'm writing here is a goodbye to my daughter that almost doesn't mention her.

The reason is that a goodbye is not about the person you are saying goodbye to. A goodbye is about losing something and learning to live without it.

Only after a week could I push myself to write these few words, and they came with difficulty, though not because of any sadness. They came difficultly because I have not been able to write for months. Or, more accurately, I have been able to write only a little and nothing of any quality. Somehow, I taught myself how to forget how to write. Whatever words I do get down are painfully inadequate, leading nowhere, fragmented into dust, into mist.

In the past month, I have tried a few times to write a poem I need to write to end a book of poems from this last year of my soi-disant life. In my first attempt, the compulsion to pun became so strong that puns push every line forward, though the forward here is more like stasis.

i. me

ink, re:mentally so

pulsating, the amygdalamy amygdala

a muggy day in the dale, birds chirpingthrough neither cloudspray nor daffodils

the Hostof the bodythat Who holds me as the held moonof the yellow light of my bodyaloft as a roundness the entire entrapment that isit's self

The words fail, even if a phrase slipped in, here or there, sounds fine to me. Most are execrable, which is a problem. In my second attempt, an attempt to start the poem over, the words are slightly better, but the poem never took care of itself, it never moved anywhere, it never came close to finishing itself

i.mI will have to start again, but I don't believe I have the will to write the poem, or any poem, not for now. Maybe never. Maybe not for years. To go from a manically productive poet to one who cannot write, in a few weeks, is a difficult situation for me. It is as if I can't speak. As if I couldn't cry if I were hurt. As if I cannot feel. As if thinking itself has escaped from me. The words I counted on care not enough for me any longer.

in up out ofthe center of self, the sleepof being, obviousas a character of flight

The idea that urged me to write these many words tonight was the idea that I might be able to write something good, to write well on this night. I thought I might be able to feel enough this sense of emptiness to find some way to write words that had some resonance to them, some enduring scent, some beauty. And maybe there is some. But not much, not enough.

And my daughter goes to California, which is a return to her ancestry. Our ancestors traveled from the East and the South, a trek of generations for some, so that my mother and father could meet on the hill overlooking Millbrae, California, and have six children. My mother is the descendant of forty-niners, so I am as well, as is Erin. I am a native Californian, born more than a century after my first ancestors moved to that state. I am happy Erin has returned home, even if it's not been her home before. I'm happy she can live somewhere where her career can blossom. I'm glad she has Jimmy. And I told her to make sure that any native Californians she meets learn that she was only returning to a home she never knew. I told her to tell them that her father is a native Californian, that she is a descendant of forty-niners.

And then I counted the miles from here to her. And then I counted the kilometers. And then the inches. I counted them to count myself to sleep.

And, still, I remained awake. And, still, I lay awake, needing to count some more.

The Last Second of Seeing Erin and Jimmy's Car (Schenectady, New York, 9 September 2012)

The Last Second of Seeing Erin and Jimmy's Car (Schenectady, New York, 9 September 2012)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on September 16, 2012 20:06

September 9, 2012

Comma Sense

"Comma Beer" (9 September 2012)

"Comma Beer" (9 September 2012)A comma is a pause.

Even a coma is a pause, a pause from a life, if not totally from living. Sometimes we move because we have in our bodies the practice of moving. One foot after the other, and neither ever allowed to hit the same spot on the earth. Forward is a movement, but not progress.

I am pausing here, taking as my companion the comma, linking my arm with its and sitting down to think. But not to say.

For the past week, for weeks, I have been doing. My time is taken up with actions, and these give me a way to spend the time. Writing enough all day at work, I hardly can manage to imagine (even imagine) writing anything while not at work. And with my daughter home for this past week, I've been working more than usual: making dinners, making a lunch or two, making breakfasts on the weekends, weeding more life out of the ground than you might even imagine was there if you had seen it with your own eyes, cleaning dishes, cleaning the kitchen, cleaning the third floor, and finally cleaning my daughter's room.

My daughter's room. But maybe not quite hers anymore. She left New York today on a road trip to Los Angeles. She's moving to the other side of the country.

But that is not a story for now. That is the story for tomorrow.

For now, I can say that I have cleaned and neatened the room, opened it up, all in the service of transforming it into something that is no longer exactly my daughter's room anymore.

Though I do have a daughter. She herself continues.

For now, though, I won't. I'll pause.

Not for long. Just briefly. Just long enough to watch my daughter head down the street and turn west, almost immediately pointing herself in the direction of her new home, her husband's new home, and my home state.

Off she goes, and I pause.

For now.

Only for now.

I hope only for now, but life has a tendency of catching up with me these days.

I assume that I'm simply not as fast as I used to be.

So I pause.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on September 09, 2012 20:10

August 23, 2012

Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep

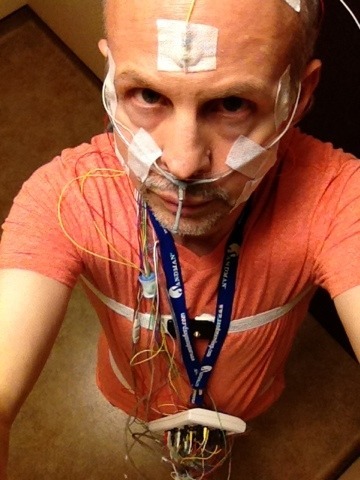

Tech Valley Sleep Center, Room 3, Niskayuna, New York

Tonight I am sitting in a room preparing to take the third sleep study of my life. The morning after my first, I suddenly had to go into the hospital for heart surgery. This time I'll just know I have sleep apnea even though no-one can tell me so tomorrow.

The one creepy thing tonight is that I was sitting alone in my room reading when Arvoo, my sleep technician, who I had yet to meet, spoke to me through speakers in the room and told me to look at the TV so she could take my picture. They watch me here as no-one ever does. Sensors monitor my heart rate, my brain waves, my breathing, the oxygen in my blood. They have cameras and microphones in the room, so they can see and hear anything I do. They will know if I have restless leg syndrome, if I stop breathing during the night (which I will), and if I'm dreaming. My thoughts are only partially private. There are probes inserted into my nostrils.

It is but 10 pm now, but I'm already tired. I may give in to sleep early tonight. I may have to. I can't do enough moving to keep myself awake.

ecr. l’inf.

Published on August 23, 2012 19:15

August 14, 2012

Over the Busted Curvature of the Earth

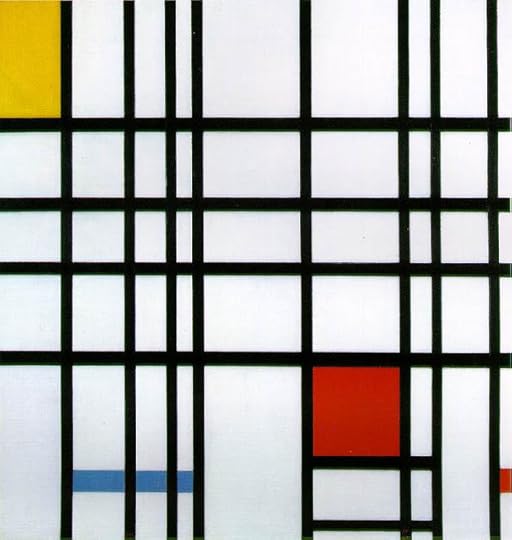

Piet Mondrian, "Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue" (1921)The day I spent today was arranged to take me from doctor to doctor, maybe as an attempt to stay alive, maybe as an action designed to give the appearance of same.

Piet Mondrian, "Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue" (1921)The day I spent today was arranged to take me from doctor to doctor, maybe as an attempt to stay alive, maybe as an action designed to give the appearance of same.So I drove. I drove the day away. At once point I took a sharp curving hook of an offramp of the road we call Crosstown in Schenectady, which became an onramp onto I-890.

I've rounded that curve thousands of times before. Sometimes, turkeys have flown in front of the car as I did so. Sometimes, I passed turkeys walking through the narrow strip of grass. Sometimes, I'd come across a stopped car or something in the road. But today I passed something I've never seen before.

On the outside ramp of this road, a guardrail protects our cars from skidding off into the shallow woods, and today I saw a young woman walking on that guardrail. As I turned the car to the right in a circle and clockwise, I swiveled my head to the left and counter-clockwise to look at her, almost over my shoulder. As I did, she looked at me as I looked at her.

She was calm, very calm. And deliberate. She moved her feet, one in front of the other, with the grace and composure of an athlete on a balancing bar. And she was certainly balancing. Her feet pointed slightly forward as she made each step.

Her calmness wasn't calming at all. She seemed calm enough to kill herself. She seemed calmed beyond the sadness her life may have borne down upon her.

And she walked along the top of that curving guardrail as if she were going somewhere, and the rail (I noted) would end in just one more step.

After entering I-890, I stopped the car at the side of the road and made a call to 911, talking to two separate dispatchers. I described the situation, noted how dangerous this act was, and the second dispatcher I spoke to said she would send someone out to investigate.

My biggest surprise was that they asked me what she was wearing, and I actually remembered. Normally, I have no idea what anyone has worn, but this time I had subconsciously thought the woman important enough to remember what she was wearing: a white skirt, a red blouse, and a black sweater. I told the dispatchers that, and told them that she had long and straight medium brown hair.

I did not tell them that she was beautiful, in that simple way that young women usually are, when they are radiant and do not see how beautiful they are. When their skin is unblemished and shines of color. I did not tell them that she walked with grace, as if trained as a ballerina. I did not tell them that when she walked she strode engulfed by her own beauty, that she couldn't repress it, that she seemed calm enough to want to kill herself.

I did not tell them that I wanted to save her from death, that I questioned whether I should stop the car to make the call, that I wanted this woman, whom I'd seen for no more than five seconds, to live.

I did not tell them that I thought I remembered what she was wearing because Piet Mondrian taught me how to remember her.

I told them my name. I spelled my last name. I didn't ask them to tell me if they found her. I didn't ask for any story.

I no longer remember if she is real at all.

I do not know how many of us walk, each day, with such grace, over the curvature of the earth.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on August 14, 2012 21:08

July 29, 2012

Love and Stone Girl

Casa Ed Baker, Silver Spring, Maryland

I'm visiting the poet and artist Ed Baker at his art-filled home in Silver Spring, Maryland. I arrived late last night, after a poetry reading and dinner out with fellow poets, so Ed and I stayed up until 2 in the morning talking.

I'll have more words about Ed and his stone girl soon, much to his anticipation, but for now, as Ed chatters into my ear, I'll write just a few words about Alain Badiou’s “In Praise of Love,” a book Ed gave me to read early this morning, and a short book, so I finished it this afternoon.

And wrote these few words.

Alain Badiou answers, in conversation, questions posed to him by Nicolas Truong, which he then translates into a book about love, and its essential nature and its transformative effects in human life. The main focus here is on the concept of romantic love, and Badiou argues against the "sceptics" who believe that love does not exist and is only a socially acceptable replacement for inexorable sexual desire. Badiou argues finally that love is a quest for truth, the truth that two people can be separate and entirely different and operate so as to perceive the world together, somehow, inexplicably, as one.

The book could have used more expansion and support of its ideas, but it exists now as something short and accessible, a readRable account of one philosopher's ideas on an issue of great human import: the existence and value of love. He ends, a few sentences from the very end of the book, with these words: “To love is to struggle, beyond solitude, with everything in the world that can animate existence.”

We can only hope it is so.

ecr. l’inf.

I'm visiting the poet and artist Ed Baker at his art-filled home in Silver Spring, Maryland. I arrived late last night, after a poetry reading and dinner out with fellow poets, so Ed and I stayed up until 2 in the morning talking.

I'll have more words about Ed and his stone girl soon, much to his anticipation, but for now, as Ed chatters into my ear, I'll write just a few words about Alain Badiou’s “In Praise of Love,” a book Ed gave me to read early this morning, and a short book, so I finished it this afternoon.

And wrote these few words.

Alain Badiou answers, in conversation, questions posed to him by Nicolas Truong, which he then translates into a book about love, and its essential nature and its transformative effects in human life. The main focus here is on the concept of romantic love, and Badiou argues against the "sceptics" who believe that love does not exist and is only a socially acceptable replacement for inexorable sexual desire. Badiou argues finally that love is a quest for truth, the truth that two people can be separate and entirely different and operate so as to perceive the world together, somehow, inexplicably, as one.

The book could have used more expansion and support of its ideas, but it exists now as something short and accessible, a readRable account of one philosopher's ideas on an issue of great human import: the existence and value of love. He ends, a few sentences from the very end of the book, with these words: “To love is to struggle, beyond solitude, with everything in the world that can animate existence.”

We can only hope it is so.

ecr. l’inf.

Published on July 29, 2012 13:43

July 28, 2012

Math in Maryland, Poetry in Towson

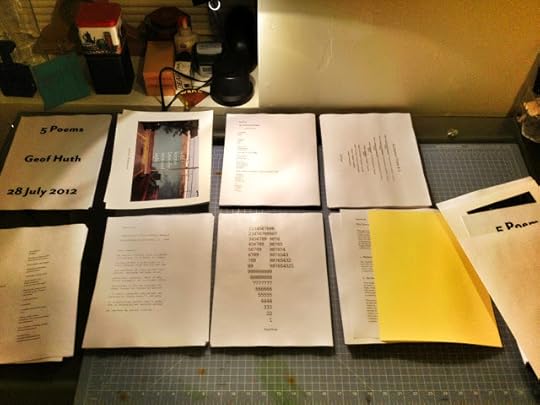

Assembly the "5 Poems" Handout, Schenectady, NY, 26 July 2012

Assembly the "5 Poems" Handout, Schenectady, NY, 26 July 2012 Today, I am flying to Baltimore, then driving to Towson, Maryland, to give a reading of "mathematical poetry." We'll see what the participants think of my brands of mathematical poetry.

This will all occur at the Bridges Math-Art Conference at Towson University. The poetry reading is a free conference event, and no registration required, so anyone can show up, though I don't expect this notification to rouse anyone at the last moment. The reading begins at 5:30 pm in Kaplan Concert Hall Auditorium, with a few featured poets: Tatiana Bonch-Osmolovskaya, Marion Deutsche Cohen, Sarah Glaz (the reading organizer), JoAnne Growney (and one of the poems I'll be reading is a poem I wrote to her), Emily Grosholz, Philip Holmes, Geof Huth, Alice Major, Kaz Maslanka (whom I haven't seen in a while), and Stephanie Strickland. After the featured poets, there will be an open reading, and the even will end promptly at 7:30 pm.

Many of the poets seem to constrain the idea of mathematical poetry to poems about mathematics, but not all, for sure. Kaz Maslanka, who has written more about mathematical poetry than most recognizes a broad range of types, as do I. So my poems include two poems constrained by mathematical prosody (rigid counting requirements in one case; pi in another), a visual poem in color that uses mathematical metaphors, a poem that carries out mathematical equations with its words, a poem that talks about numbers and uses a little mathematics, and a visual poem that is nothing but a pattern of numbers. I explain all the poems and why they are mathematical poems in my handout, which is not a book this time. Instead, it's a sheaf of paper resting in a white envelope upon which I've written the word "5poems" in cursive script and my signature.

I'm expecting an entertaining day, and I get to sleep with Ed Baker at the end of the day.

Well, not in the good way...

ecr. l'inf.

Published on July 28, 2012 05:44

July 18, 2012

Last Night in Paradise

Geof Huth, "My Busted Heart" (found concrete slightly sculpted & covered with India ink), 3 July 2012

Geof Huth, "My Busted Heart" (found concrete slightly sculpted & covered with India ink), 3 July 2012I move in the sense of leaving. I move in the sense of staying in place and feeling the movements of my body. I move in the sense of bringing beings to tears. I move in the sense of stillness being merely the process of being moved through space without volition, without even recognition of movement.

We move.

I once said, "Every word is real." Actually, I wrote it. A written word endures, at least sometimes. It remains as a track back to its creator, even when its creator is absent, has left, died centuries ago yet still leans, through your eyes, towards your ear, to whisper what you always never knew you wanted to hear, maybe even what you always knew you never wanted to know.

It is too late. You already know it. You suffer now the burden of words, of meaning, of human interaction even in the face of graceless death. Because death doesn't impede culture. Culture is about endurance across time and the generations born within in. Born between piss and shit. Born between sunrise and sunset. Born between twilights and flickerings.

A human, though, a specific human, any human, does not endure, does not even stay in place. The body takes many forms, yet the final form is always death. Our final disposition is always death, regardless of the means of that disposition: scattered to the winds, dropped in the drink, buried in boxes buried in dirt, piled high.

We might reach the heavens if there were heavens to reach.

The infinity of a life, though, is what continues us, even as we realize that it is not a real infinity. But for most of us, and for most of our lives, we live as if life were limitless, because we don't know when we will reach that limit. Even if we attempt to reach that limit sooner, we don't know if we will succeed. If there is blood in us and it beats, if there is breath in us and it repeats, we will continue.

Sometimes in circles. Sometimes backwards. Sometimes forward.

And forward is the worst. Forward is the direction of least stability, the direction least known, least probable. And most potent with possibility.

So we move. So I move. Forward. Into possibility. Into rivers and words. Into friendships and beers. Into riding and singing. Into windows gushing with light.

Into windows gushing with light.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on July 18, 2012 21:26

July 2, 2012

3 Books

St John the Evangelist, Schenectady, New York (30 June 2012)

St John the Evangelist, Schenectady, New York (30 June 2012)While walking many miles through the small city of Schenectady the day before yesterday, I stopped for the first time in the small bookstore run by the Friends of the Library group of the Schenectady County Public Library. I had never believed the store would carry anything of interest, but within a couple of minutes of entering its doors I ran across a copy of Anne Carson's An Oresteia, translations of three Greek plays by three separate dramatists. Being an avid reader of Carson, I picked up that book. (This was, very strangely, the second book I had bought in the course of a few days that had Oresteia as most of its title. The other was a translation of Aeschylus' Oresteia by Ted Hughes.) As I continued my search, I found a copy of William Styron's Darkness Visible: A Memoir of Madness, which I have often meant to read and which slips into my current phase of reading memoirs, so I picked that up as well. And, finally, I ended with a surprise, an unexpectation, a book that made maybe I had less obvious reason to pick up, but I did: the second printing of the eighth edition of Arthur Rose-Innes' Beginners' Dictionary of Chinese-Japanese Characters and Compounds, from which I thought I could gather insight and enough crassly assembled knowledge to create visual poems that used Chinese characters meaningfully. The total cost for the books was $2.16, but I told the elderly woman who was the cashier to keep the change. She was amazed at my generosity, but I explained, "At $1 a book, I think I can manage."

But, of course this was inevitable, these are not the three books I plan to write about today. Instead, I want to write about three books of poetry I read on the same day almost two weeks ago. I rode busses (apologies, but I can't accept the American spelling in this case) three times that day, and I read each book during a separate bus ride. My interest is almost not at all in the books themselves, though, but in my reaction to them, and thus about our reactions to books and how they can be both well reasoned and spurious at the same time. I'm interested in how the concept of quality accrues and grows in the fashion of coral, holding fast to some base belief, but extending out to encompass anything within the reach of that belief.

Book 1: Rachel Loden's Dick of the Dead

From the title on, this book is a joy of wordly imagination. Swirling around the pathological post-Quaker self who was President Richard (AKA Dick, AKA Tricky Dick) Nixon, the title puns against the collocation "the quick and the dead," for Nixon now continues as a person wholly dead but a personage and personality that cannot sift itself out of the imagination. A man of great intelligence and drive, he became a beast driven by his darkest self, paranoid, haunted, it seems, from the sense (whether true or not) that shenanigans with the voting in Chicago in 1960 cost him the presidential election, and even becoming president did not erase the scar of that November night when my mother herself took me, only five months old at the time, into the voting booth to vote for his opponent, a man named Kennedy).

But I've drifted of the plane of the book itself here, even as I refer, in fragmented and refracting ways, onto stories and symptoms that inhabit this book. But maybe it's not that I like about the book, maybe it isn't even the poems themselves. Maybe it is the fact that the book has a tinge of Finland in it. Finland, my faraway and neverwas home. The book opens with a dedication to two people, one (Jussi) bearing a Finnish name, and occasionally a poem somehow identifies itself with Finland, even if in passing. Finland, maybe the only country in the world with a name in English that begins with a letter, a sound, not native to its native language. To me it is Suomi. Postage stamps have always shown me the way.

The book rebounds off the events of Nixon's reign in the United States. Nixon Rex. Tyrannosaurus Nix. A man vilified at the end of his term, the only president to resign from office, but one somehow reborn after opening his memoirs—a book that seemed to claim to be about nurses—that he was born in the house his father built. And this book of Loden's in filled with such references, not these, but similar ones—sometimes obscure references to strange sentences spoken by or in the presence of Nixon and sometimes recorded on tape that wound and wound through the conversations of a presidency.

Still, you know nothing of the poems from me. I've kept them secret. I am merely hoisted into the seat to fly this airplane of words by the force of Loden's own words, the magic of her manner, how the words are neat and pleasant, beautiful yet raucous, given to great bursts of imagination, and stunning in their drive. (Nearly meaningless, I realize that. But it is not a description of the words that reviews a book; it is a description of the feeling of the words in a body that is.)

And I feel these words and their imagination. Loden's general style is long-lined couplets enjambing like a car going 75 when the driver simultaneously slams on the brakes and swerves the steering wheel counter-clockwise to return to where she's come. We are thrown akilter by Loden's words, her mastery, her mistressery, of the language, how she is erudite and palpably of the hoi polloi all at once, alive with history and with the culture of the Popinstan culture that rains through the holes in our umbrellas, even on sunny days. So a poem about S.C.U.M. Manifestoist Valerie Solanas, the sculptress with a knife into the white white chest of Andy Warhol until Frankensteinian stitches puckered it almost into a vortex that could suck us back into his empty bloodless heart, faces a poem that is a rewrite, homage, and parody of Robert Creeley's most famous poem, ending here with

floor it, he sd, for

christ's sake, 4.9

seconds to 60 mph.

You can almost hear Loden torquing that steering column.

Book 2: John Allen Cann's Solitude in the Shape of a Woman

Give me a canon, and I ask for something else. I do not want to kill anyone with the accepted, the sanctioned (a word, I note, that can turn on itself), the tried and tired. Sure, I might like those canons, and might even polish into some other poem a few words raised off the surface of its barrel. But I don't just want a canon; I always require something else. The surprise, the hated, even the unknown. Because of this, I buy books of poetry by people I've never heard of if something about the book catches my interest. It may be the description of the poems, but never the blurbs. Those blurbs don't move me, something that pains me, because it seems possible that blurbing may be my true calling, that I cannot write poems so well as I can write pithily and forcefully about them. Alas, so true. Sometimes it might be the design of the book that catches my eye.

In the case of John Allen Cann's Solitude in the Shape of a Woman, which I picked up at Powell's in Portland, Oregon, it was the production values of this little book. Twice as wide as it is long, the book was handset, the title an author's name pressed deeply, and in silver foil, into the blue cover becoming dingy, and illustrated with a muscular little asemic sequence of three black brush strokes, the face of the book itself demands attention. And inside the pages are of heavy paper the color of French vanilla, the titles of each of the thirty-three tercets flush left and in small capitals, and the three lines of each poem set farther from the gutter and reaching languidly across the page, most of the lines carrying a breath or breath and a half of words that urges a reader to reach for the right edge of the page, and at least one line so long that it must be cut in two and its remain inset even further to the right having broken past the invisible barrier of the margin.

The poems, I fear, are a little maudlin, but human for that fault, and they tell the story of a love found and then lost—the order of those modifiers of "love" not right for the soul. The book even opens with an epigraph, stolen from a discarded poem of Cann's, that testifies to a pain in continuance: "For The Woman Who Comes To Fill This Solitude" (capitalization as in the original). As short as the poems are, they still manage enough space for euphuism and a little empurpling. Even I might have avoided a phrase as romantic as "a windswept sapphire sky," even as I would have struggled to insist a hyphen not in existence ("winds-wept") to make the weepiness even more unbearable. And the poet's ending inscription to a friend of his

Kathy,

That the Logos may fill us

with Light.

your friend,

John

Christmas '87

made me wonder if Kathy were the solitude of the poem, a solitude I thought less truly that than a loneliness, but the word "loneliness" would be impossible since it wouldn't have been poetic enough.

Still, the poems showed a man of reading and a man running through the stations of his pain, someone trying to paint a reality but a little too reluctant to use the blood that would be necessary to make these right. Still, I thought the poems too weak, the poet too given over to words almost archaic. Still, the poems somehow still hurt me, maybe because their flailings demonstrated a real hurt, a humanness, and a human attempt to voice the self, to leave the self behind, impressed into the rich deep fibers of the page.

I allowed the poet a little misericord suffused with a dream of frankincense and the single clinking of the thurible. In genuflection with rise or fall.

Book 3: Robert Creeley & Archie Rand's Drawn & Quartered

Why did I pick up this book, also at Powell's? Was it because it was by Creeley? Not exactly, but the fact that these poems are not, so far as I recall, in the two volumes of his collected poems meant that I would not have read them? Was it because it was a volume by Granary Books? No. I might enjoy some books by Granary, but, more often than not, the hype of their books overwhelms the hypodermic pump of the books themselves into my veins. To a great degree, it was because this book was a verbo-visual affair.

Archie Rand is an artist whose "humor, quickness, and lack of pretension much attracted" Creeley, and Creeley ended up writing fifty-four poems in one night, each one written against the example of an Archie Rand drawing. That seems an endeavor to my liking: image and writing, writing serving as textual illustration to the pre-existing drawing, a mien almost like a one-panel comic, and a forced servitude that required Creeley to perform the poems, to write them freely and extemporaneously onto the same page as the respective drawing, to write as a form of performance. These are essentially the basic tenets of the major kinds of writing I do.

And yet. Well. And yet. I simply hated this book.

I have almost never hated a book of poetry as much as I hated this one. Hate. It's a strong word. I used it relatively infrequently. Rand's drawings were muddy in their reproduction and artless in their movements. Certainly, he has a style that is slightly cartoonish, but in a scrawl that he then muddles with watercolor or a wash of ink. The artlessness of his work is meant to be the art, but many of these images devolved into dark vortices without contour, into black holes of humorlessness.

Yet the pictures are the best part of the book.

This is fairly late Creeley: 2001. So maybe he created the poems in 2000. Creeley had already descended into his rhyming phase, a black miasma he could not manage to extricate himself from. The man had no ear for rhyme. As a matter of fact, let's admit it, what made him great, when he was great, and he often was, was when his ear seemed to lead him astray. The jaggedness of his lines, the curt pirouettes, were a kind of stumble, and that stumbling voice, something we heard as a whispered staccato, was the magic of Creeley, so maybe it was earlessness that made his poems great.

But keep the man away from rhyme. At their worst, and most of them are, these poems are little more than bastardized clerihews. Not even thoroughbred clerihews. Let's take a poem chosen at random:

For years I'd thought

such bliss as this could not be bought.

While I waited,

my desire itself abated.

If that doesn't sound like a clerihew to you (though, yes, I know, it doesn't quite follow the form), then you don't know what a clerihew is, or you cannot hear an earlessness. To be fair, clerihews are exactly what they need to be, humorous quatrains, and Creeley is playing with humor in this poems. But it's like playing with file . . . near a drum of gasoline, in Creeley's hands. The poems mimic the artlessness of the drawings, and they are such servants to the images that they merely illustrate. They barely even extend the drawings.

Only one poem did I enjoy, and it is the most jagged, the most Creeleyesque. Oh, it still rhymes (AABB, not quite Swedish), so it's not great, but it has a kind of half-rhyme/eye-rhyme going on between the second and fourth lines:

One word

I heard

you said

you read.

Not great, but a bit of recompense for a poor bus ride's set of poems

Booking Out

What's interesting here to me is that the poet I should have loved I hated, the poet I should have hated I held some warm feelings for (even if queasily), and the person I expected to be offputting I loved so much I wanted to bear her children (though I thought I have something backwards in that metaphor). Thank goodness I'm not a poet. I'd hate someone to expect me to entertain them well.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on July 02, 2012 19:06

June 14, 2012

Poem about Procrastination

I'll get

to it

later.

(created during a conversation with Andrew Wittenberg in Princeton, New Jersey)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 14, 2012 20:49

June 6, 2012

A Poetics # 98: Success

Geof Huth, "MMAP" (6 June 2012)

Geof Huth, "MMAP" (6 June 2012)Today is June 6th, 2012, or 6/6/12, a sign, and a memory of the future that has become the present. Months ago I wrote a poem entitled "Avenue of the Americas, 6 am," and my plan at the time of its construction was to read it at 6 am on the Avenue of the Americas (AKA Sixth Avenue) in New York City, specifically on the northwest corner of that avenue and 53rd street, a point in the city that I know well, the place where I imagined the poem being spoken by the narrator (even as I was writing it), and the spot specifically identified in the poem itself. This is a long poem, because I am focused on writing long-form poetry at the moment, and it's imagined as a performance early in the morning before the city has fully awoken. Yet I did not perform that poem on that corner today.

I have distributed the poem to a few friends since its creation more than half a year ago, and one or two people have read it. I will probably not distribute it anymore, nor will I try to publish it for now. I will dream, instead, of performing it on that corner of New York City, on some future but less perfect June 6th, to an audience that will likely not be there but will view a digital surrogate of that reality sometime after the event. And almost no-one will see it there, and it will be a success. It will be a success because I will have made it by writing it and made it again by performing it as it was meant to be.

As I told Nico Vassilakis, who didn't need this reminder, in January, "We are just here to make. So make. So make. And make it as well as you can." We succeed at poetry for the poetry we make, and maybe those poems succeed by sometimes affecting people, by burrowing into them for good. A failed poet is one focused on fame in this so little fameless world. A failed poet is one who builds a career more assiduously than a poem.

As I also told Nico, "We don't have to be great poets. We have to be dedicated ones." We have to create. Our success is our work, read or not, loved or not, but lived and lived hard because we have made it that way.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 06, 2012 20:54