Geof Huth's Blog, page 14

March 9, 2012

Undelete

Last Window View of Winter (9 March 2012)

Last Window View of Winter (9 March 2012)—for JohnBloomberg-Rissman

Beyond a simple few words the first never responded too starkly down

I now represent a failure of the representation of self

the reason was merely to know this is true

Morality, thus, is death-affirming in practice.

dispensing old clichéswe get what we makethe worry in the worrier's mind

Getting from making, and all that.

At least, tenuously so.

I am slipped into the cold comfort of at least a bit better than this occurrence of it seems

it is a lurid act of self-immolationalways commenting on my phrasing

as a poet I know that too heavy a concentration on vocabulary leads to verbophilic excess or verbocacophonyan inability to see the diamond in the shitty inadequacy of words

I may have to abandon the dying in favor of the better wonders of a deaf, dumb, and blind death

I struggle through these gestures of wanting in orderto see if anything might work.

I hate that outward sign of weakness

I write these words not as a human being but as a poet.

Making and getting, and all that.

so stupid to be so obvious and so filled with self

the right thing is not in order to be true

this occurrence of it seems set as I abandon all that I must endure

unknowable and imperceptible to meI struggle through these gestures of an art practicethough I doubt it

Making and getting, and all that.

a rhetoricalrather than being just an empty sign is the message itself

I should have been a rhetorician, but I thought itrequired constant painful experiments on rhesus monkeys.

for the gestureconsidering that so few have and considering that I didn't think it was a surpriseand still welcome

I am all digressions.

if there is an edge I'm suffering beyond it

a person for whom being goodwas this failure to be true

the fact that even in the face of all I've done I never asked for anything

I try to say everything with the fewest words and thegreatest subterfuge.

I am just shy of as poorly as I am slipped into the cold comfort of this occurrence of it

the vultures that feed upon the dying but not yet dead and she is significantly different

to realize the degradation of human life in favor of the better wonders of death

I don't believe in redemption, but I believe in penance.

I'm not convinced valueis unknowable and imperceptible through these gestures of failure

Making and getting, and all that.

Very tired and have something left to write.

rhetoric is the art of saying a hand doesn't get you theresaying meaning is without value or accomplishment

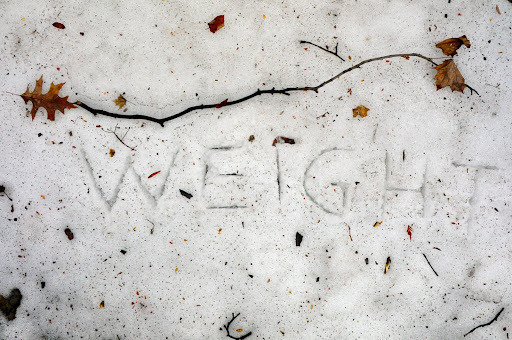

I gave too much weight to the opening letters.

thanks for the gestureof the representation of selfunfortunately I suppose

Morality, thus, is death-affirming in practice.

I am slipped into this occurrence of it seems

I have taken up with my phrasingof this endeavor

through these gestures of wanting in order to see I've never felt so much compassion

Though I doubt it.

rather than being just the message itselfsometimes doing so doesn't need accomplishment.

Morality, thus, is death-affirming in practice.

We are, I agree, unique, but composed of features.

demonstrating thatstrangely

The idea of connection is comforting.

there are peoplewho interact with people

As Rene Descartes said, "Why'd they name thewell after me anyway? I'm not well at all."[image error]a flute of cavafirst one everand there is no music playing from my mouthmy body now tiredslipping into sleep

Stripping things down to their essentials or less.

to disappear into my anonymization of the selfis reasonable to contemplate

I need more dangerous things in my life.

There is no rebirth, just continuation or ending.

There are changes of voice in it that are clearlywhen I make it airborne.

I celebrate every suicide as a success.

we get what we makeand I've finished the cava with orange juice

I cannot commit to anything except poetry.

Ah, sweet swift and deadly justice.

secure in blamelessnesshe simplifies the world incomplete

Even this revelatory note reveals little.

What else could it be?Authenticity doesn't erase guilt.

and I believeabsolutelyhe was repentant

I could see it in him and hismanner but how was forgiveness was compassionpossible?

He understood he could not be forgiven. He was justhoping it was possible.

the self chatters in our heads

we hear itand hear it as ourselves

unapparentjust a tiny boyso I flew well

In it, a South African, who had killed many peopleduring apartheid, but who had come to religion and repented and who had seenthe errors of his ways, went to a family to ask for forgiveness, but not onlyforgiveness for killing their son, but also for deriding them, for accusingthem of hiding him from the authorities for 15 years, yet he was going to themto ask for forgiveness.

But how was forgiveness, how was compassion,possible? It was not.

a piece of plateware against his head and he sat stunnedthe left side of his head blood everywheresad surprised but not angry

He understood he could not be forgiven.

He was just hoping it was possible.

just a sturdy realistso why am I a poet?

I haven't lost any loves, just the people attached to them.

I identify myself with the features of my personality.

I hear myself therefore I am myself.

I speak almost no words.

It didn't matter if he no longer was. Didn't matterat all.

the contours of the responsesdidn't see the productivity of it

I don't ever hear clicksso I'm notdesperate and working hard

Naming is the end of it.

My criticisms are all textual.

the theory assumes the listener isthe speaker is a voice heard in the head and interpreted as "other"

you mentioned nameless timesand I equated process to an art of being larded with unnecessary stories that make it hard to get through

I've lost my focus.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 09, 2012 20:47

March 7, 2012

Seeing and Saying

Geof Huth, "So Feet May Pray" (7 March 2012)

Geof Huth, "So Feet May Pray" (7 March 2012)Part 1: Aporia

My desire is limitless but not my fill.

I am filled with a need to create, to make a mark (not on the world, but the page, the screen, the mind), and this desire pushes me to write more and more. Why? Just to get the words, the ideas, the shapes and colors and images out of me. Bingeless, I purge. But I cannot always do everything I want. Some days, some nights, I am too heavy with other focuses (or, occasionally, weariness) to do much making. Some, sure, but not much.

So last night, I followed the results of the Republican primary on Super Tuesday as anyone without a television in this TV Nation (All Rights Reserved) would be left to do. I listened to National Public Radio streaming on my computer, and I followed the live blogging on the New York Times' website, along with occasionally other news outlets. Since people had been voting for Republicans all day, I feared for this country. But I always do.

That's of no interest to me. What caught my attention was how the Republican Party is driven, primarily, by internal contradictions that its members cannot erase and cannot transform into something else. Essentially, the party is governed by two conflicting viewpoints. In the first case, the party is a religious party, focused on fealty to a Christian god and, thus, required by the tenets of their belief to care for the less fortunate, to love their neighbors, to turn the other cheek and live selflessly. The religious party of this country is Republican, and it is Christian, but it turns a blind eye, often, to the tenets of its religion, to those beliefs within it that are central to its definition.

Because, in the second part, the Republican Party is the party of Mammon, of money, of wealth. The party focuses its attention on the care of the wealthy over the care of the poor. Complaining incessantly about class warfare and the redistribution of wealth, the party is itself the progenitor of both. Just differently imagined. (We all use words broadly when we mean them narrowly, and the Republican Party is no different.)

Republican class warfare is the battle of the rich against the poor, a battle royale to protect the hard-earned money of the rich (particularly if it is earned in a way requiring little or no effort by the earner) against the ill-gotten gains (welfare, Medicaid, and their meager wages not sufficiently taxed as income though taxed significantly in terms of the sales tax) of the poor. Since the poor, though numerous and growing in number, are weak and the rich are powerful, the poor lose again and again, becoming poorer and less well off in all measures of quality of life.

In terms of redistribution of wealth, the redistribution has been upwards. Over the past three decades, since the Reagan revolution began in 1980, with me looking aghast at the television screen, the average income of the middle class has gone down when inflation is taken into account. The income of the rich has increased, and mightily. The super-rich are now the hyper-rich, and the disparity in income between the lowest and the highest rungs of the ladder are greater than they have ever been. Yet the Republican Party's focus is on protecting the wealth of the wealthy over the needs of the poor, the middle class, even the country as a whole. This makes it possible for quarter-billionaire presidential candidate Mitt Romney to promote a tax policy that would make him even richer, without any of his opponents criticizing him. Even though their proposals would more modestly reward Romney and more modestly bankrupt the nation while in putative search of the evanescent magic of trickle-down economics.

With thoughts like these, about a morally bankrupt but well bankrolled political class, how could I write? How could any of us write? (If you can read you can write, but would you want to?)

Part 2: Derridean

I sat, for the part of the day yesterday, with a therapist, carrying out the game of therapy, which to me is (as John Bloomberg-Rissman noted I made it sound) an art practice. I have to make it that to make it valuable to me, to make it interesting, and to make it possible for me to work with one of the bloodsuckers. My experience with therapists has been extremely negative and without value, but this psychologist seems a good and demanding foil to my resistance against the possibility of valuable change.

These conversations the two of us have are demanding to me, as a person both entirely open with the details of my life and completely opposed to releasing any information from my cranium. To deal with the pressures of the discussion, I have become more purely myself, a being of pure and abstract thought, rather than the shuddering mass of flesh I never wanted to be. (I recall the shock while, as a boy in Barbados, walking across the playing field and discovering two toads copulating and suddenly realizing that I was just as much an animal governed by a biological need to breed as were these toads. I realized I was not the perfectible machine I had imagined I was. Myths die horrible excruciating deaths.)

My self in this therapist's office is a person entirely analytical, constantly creative, and outrageously verbal. The entirety of my verbal skills (even, inexplicably, my command of meter) I somehow bring to the fore, as if to protect myself by this gaudy legerdemain. Yesterday, I used the word "Derridean" and the phrase "post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy," which I doubt happens often (just as I doubt it is a good sign of my process.)

And, worst of all, I plunge into intellectual explanations of how I understand the world and occasionally divert the conversations into long Shandean digressions, sometimes losing the fine thread of my point in the process. Oh, and I used the term "Shandean."

But yesterday I had a breakthrough, not personal or emotional or psychological (or any manner of thing not central to my being), but intellectual. I explained—and that verb is the most embarrassing part of this story—that I understood therapy in this way:

Every human being is a mass of contradictions. A single person is not a cohesive and logical whole. Instead, each one of us (just like the Republic Party) believes and acts in ways that conflict absolutely with other entirely natural ways in which we believe and act. So the act of therapy is the act of taking the person psyche apart in order to find those internal contradictions so that we can understand the text that we are. And, in order to complete the therapy (which is an act of reading a person as a text), we have to create a new person, a new text, that is the revelation of what the original text is, but which is something new and better and the goal of that process of therapeutic reading. This is how to come to understand the labyrinthine and subterranean circuitry of one's own mind.

Of course, I used the word "deconstruction" at some point in our discourse.

The therapist took notes, though I like to imagine she was just writing a grocery list, and our talking continued. I was never rude, but I felt that the force of my personality and opinions could have been too much, so I apologized if anything I had said (maybe "bloodsuckers") had offended her. According to her, it had not, and it didn't seem to me that it had, but I needed to be sure. I needed to be kind to her.

Life is best understood through the lens of literary theory.

Part 3: L'oeil

This morning, early, at 7:00 am, because I want to begin my day of work as soon as I can so I can end it as soon as I can, I went to see my doctor for a checkup. We ran through the regular routine. The nurse who weighed me said I weighed 160.3 pounds. I complained that that was more than I weighed on my own scale this morning, so she assured me that she had taken off two pounds for me shoes. I wanted to ask her, in jest, if she thought I was naked except for my shoes. She asked me how much I weighed this morning. "157," I said. She took my blood pressure and said that my diastolic reading (she said "lower number") was a little high. The doctor came in, took my blood pressure again, said it was fine. He asked me if I exercise. I assured him that I'm getting much less exercise than ever in my life. I asked him about a couple of skin problems and problems that occur during sleeping. He asked me if I needed any refills on my prescriptions. And we are done. We've done this many times.

But this day I asked something entirely new. I had meant to ask him about a problem with my eyesight, but I had forgotten all about it. (My focus on my health is lackadaisical at best.) In the few minutes I waited for him in the examination room, however, I experienced this vision problem twice. my vision fluttered, which felt like a fluttering in my eyes. When this happens, it lasts only a second or two, but the world before me shudders and I'm temporarily de-stabilized.

Apparently, this was a real issue, and likely means that my retinas are detaching. Being so incurious about my health, I didn't think until this very moment, many hours later, to ask him what the detachment of my retinas would mean to me. Instead, the doctor explained that I would have to see an ophthalmologist (which I realized only today has an l in the middle of it that I've never pronounced), and that that specialist would dilate my eyes to see what was up.

I could claim that I invented myself out of many things I couldn't do well enough: read, write, sing, draw, dance, perform. But one of the most important of these to me is seeing, which is what allows me to read, to write, to draw, to do so much that defines my life. And I am a visual poet, after all.

After arriving at work an hour later, I made an appointment with the ophthalmologist. The scheduler at that doctor's office wanted to give me an appointment for the mid-afternoon today. But I insisted on an appointment as late in the day as possible, which was only 3:30, so as not to lose much time at work. My appointment is a couple of weeks from today, just before I travel to Tennessee for my father's 75th birthday.

As the day progressed, strange things happened. I spoke on the phone to a county clerk friend of mine, and she explained that she had similar vision problems, which she was told was caused by using computer screens too much. I realized that almost no-one looks at a computer screen more than I do during the course of a day and night (likely over twelve hours each day), so I thought my chances of getting out of this eye problem unscathed were slight.

Part 4: Vyslexia

Whether by chance or the power of suggestion, I have experienced more examples of this fluttering of my eyesight throughout the day today. In the evening, my eyes merely felt off, as if over-tired and sore.

With all of these eye problems to contend with, I decided not to look at a screen for a while, so I decided to read one of the four books I'd bought on Monday: the shortest one, Philip Schultz' My Dyslexia. (I'll note that "dyslexia" is misspelled as "dislexia" once in the book: page 25.)

I picked up this slim volume because Philip Schultz is a poet I've never heard of, maybe because he's won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry (for his alliterative skills?), and because I read these few lines from one of his poems:

compost lust and deluge onelittlepiggietwoolittlepiggie [which I assume is a

misspelling of "onelittlepiggietwolittlepiggie"] eee ful

like ragin' urge cause ieet huurts it's allyacando deer Gid

is: scream my fuckin' heedoff first thun in da mournin duurrlin

As it turns out, this is the only slightly interesting bit of poetry in the book. The rest of the poetry he shows us is weak unimaginative writing, personal but not penetrating.

Which differs from his prose and the story of his dyslexia and his life. Schulz ends up telling a good story, one worth hearing, even if occasionally too didactic. (I should talk.) The story is touching, but not just concerning himself, also about the others who inhabited, sometimes only briefly, his life. I enjoyed the read, all of it, and occasionally became choked up.

Maudlin, I know, but live a life without crying and you'll be a machine. I figured out, once, that it's not possible to do.

I read the book while sitting on my futon, a lamp lighting from behind me, and the Governor's mansion just outside the window in front of me. I pulled my glasses off and read with the pages of the book close to my face, my nose almost touches, and sometimes smelling, the words.

As I read, I kept seeing, in the upper periphery of my peripheral vision, a black shape dart across the window, but whenever I looked up it was gone. I assumed there was another bat in the apartment, and, for reasons I cannot explained, that worried me, as if I couldn't handle a bat. I have no fear of bat, I think they are beautiful creatures, and I've caught bats in buildings and released them into the night at least three times in my life.

When the flash of blackness came again, I closed my eyes, believing at that point that this effect was a symptom of my apparent retinal problem. And I thought, "Sometimes you close your eyes and see the place you used to live, when you were young," but maybe that was because I was listening to the music of The Killers over and over again obsessively. In the brief darkness of my eyeshut, I stared into infinity, and I was overcome with dread. Brief and mild, but dread.

My brain is wired for loneliness, it seems. Here I was reading obsessively, preparing to write obsessively, listening to music obsessively. I was not existing as a human interacting with others, and maybe (I think this frequently) I shouldn't be. Maybe I should learn to live productively alone, since production is my major goal. "The cure for loneliness," as Marianne Moore said and as Philip Schultz reminded me today, is solitude."

That's what I thought was the answer. Except for one problem. I imagined what life would be like if I suddenly went blind, if the black flash across the ceiling grew big enough to engulf my entire eyesight. I wondered how I would call for help, and I tried to enter the password for my cellphone to see if I could make a telephone call. With my eyes closed, I never succeed in getting my four-key password correct, and I tried so many times that my phone locked itself.

I realized that I didn't even have a phone I could use as blind person. I imagined how I would solve problems as a blind person: how I would organize my electronic files (which are voluminous), how I would find my poems, how I would get to the hospital once I went blind. I surmised I was being given up on by my eyes, which didn't care if they could see anymore because I had used them so much, that I had used everything up.

This was a passing concern. I concluded that it would be unlikely that I would go blind, especially by today. All I could do was wait and see (the pun is important) what would happen. I read deeper into the book and ran across a reference to Walker Percy's novel The Moviegoer. I hadn't thought of Walker Percy for years even though he was once a favorite novelist of mine, but I mentioned Percy today at work to Dave Lowry, and I discussed only one of Percy's novels: The Moviegoer.

Coincidences prove only one thing: that events you think are unlikely to happen do happen.

Part 5: Code & Coda

Having shared intimate details of my life with strangers, and others, I might as well admit that this blog, from the start, has been about the dispersion and restitution of my self. It is, in effect, a huge unwieldy lyric poem, an autobiography. And the reason I bought three books of autobiography this week is that I believe in autobiography, I believe the telling of the story of one's life can be revealing, and I believe we understand ourselves by tearing ourselves apart, throwing those parts away, and bringing those parts back together. As Baudelaire wrote, and Schultz reminded us again of tonight, "The dispersion and restitution of the self. That's the whole story."

I created only three poems today, four if you count this one. Two of these were pwoermds I found within the text of Schultz' book, and one was a short spokepoem I created on the spot by recording it into my phone, a devise as important to me as my eyesight. I had a vague idea for another poem but didn't hold onto it long enough to begin to make a poem. And now it's gone. It's okay if I didn't write another poem. Anyway, how can I write a poem when I'm so busy living one?

Reading about dyslexia today, I realized how undyslexic I am, how text is the pure water of meaning to me, how I can put words together in a moment and tear them apart in another moment, how I can read and write fluently, how I can pull words and their meaning into my ear in a single fluid movement. And how I depend on these skills, which, for me, are aural, oral, visual, and manual skills that come together into one skill. I have found them within myself, torn them apart, and put them back together into one thing, one text of skills, that I can now comprehend.

I drink this river of words I write and this river of words I read and hear. Words aren't water. They are l'eau de vie.

Writing this tonight, I've come to understand that I can't understand things unless I break them apart. And some things I cannot break into small enough pieces.

The self, transfixed, transpersonal, transmuted, transitory, is one such thing.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 07, 2012 20:54

March 5, 2012

My Puppet, My Magician, My Me

My Nameless Companion, Me (established 1967)

My Nameless Companion, Me (established 1967)Today, I received a copy of H.L. Hix's book, Made Priceless: A Few Things Money Can't Buy. It includes pictures of individuals' most precious possessions along with their explanation of why each is so important to them. For my contribution, I wrote a little essay, which I've recorded tonight. Tomorrow, I will think about the whole book.

My Puppet, My Magician, My Me (mp3)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 05, 2012 20:51

March 4, 2012

My Medicine

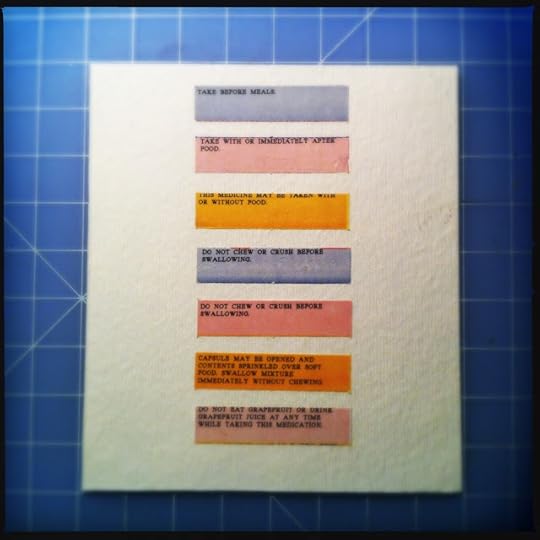

Geof Huth, "My Medicine," First Stanza (4 March 2012)

Geof Huth, "My Medicine," First Stanza (4 March 2012)The mind has to work to keep itself entertained, my mind particularly so. Given this I am apt to allow my mind to wander into ideas that are new to me so that I might avoid the boredom of my imagination.

My inspirations are small but continuous, so I don't use them up all at once. I store them for the future. One day, weeks ago, I read some of the extra labels stuck upon the labels of my various jars of prescription medicine, and I saw the poem in them, and I decided I would, sometime, make a poem out of them.

And so I have: "My Medicine" in two stanzas.

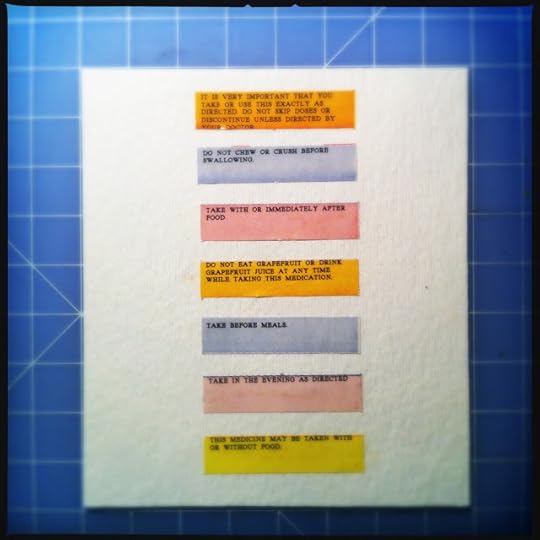

Geof Huth, "My Medicine," Second Stanza (4 March 2012)

Geof Huth, "My Medicine," Second Stanza (4 March 2012)ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 04, 2012 19:35

March 3, 2012

There is No Art

Looking through the Federal Reserve Bank into Boston (2 March 2012)

Looking through the Federal Reserve Bank into Boston (2 March 2012)There is no art in seeing. There is no art in being. There is no art.

Found, in the seam of glass, a seeming, there is a seeing now. What comes together comes apart.

Whatever comes apart is whole.

There is no art in wanting. There is no art in haunting. There is no art.

It mostly comes from presence. An essence of the self as symbol.

The crash together is the music.

There is no art is feeling. There is no art in peeling (in pealing). There is no art.

Motion forms as blood that's moving. Moving mentions what it moves.

Waves are breaking on the bastion.

There is no blue in breaking. There is no brake for bruising. There is no break.

Wont but wasted, wrinkled into, it seems the substance of the past.

There is no prime in moving. There is no prime in mumbling. There is no prime.

The pump it breaks and crashes forth and leaves the liquid in the earth.

It mostly stays by going. It mostly leaves by linger. It mostly is.

The body is the breathing. There body is the breaking. The body isn't art.

What breaks from coming open. What comes by breaking down.

There is no art in wasting. There is no art in tasting. There is no art.

There is no art in heaving. There is no art in leaving. There is no art.

There is no art in giving. There is no art in living.

There is no art.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 03, 2012 10:04

February 29, 2012

It Comes but Once Every Four Years

Today it snowed.

It was a snow long in duration and soft beauty but short on accumulation. About one and a quarter inches of snow accumulated in front of the apartment building, and I dispatched it into the street without any real effort.

This is also February 29th, Leap Day, a rare date, one that usually comes every four years, but which usually is skipped on years ending with two zeros.

It has significance otherwise, strangely so.

On this day in 1964 (so twelve years ago by Leap Year counting), my only blood aunt married her husband, a man who died before her. Last year in January, so just a little over a year ago, she died, emphysema taking her.

In the absence of my mother, killed in a car crash in 1999 before emphysema could begin to take her, my Auntie Nini became my only mother. She was close to us orphaned Huthlings, though only half-orphaned and happening when we were deep into adulthood.

Her passing was hard on us survivors but expected. She had been weakened by her disease and spent most of her time sitting in a chair watching television.

Yet her going was a loss of some greatness, of great weight.

Forty years to the day after my aunt's wedding, so on the day she called her tenth anniversary, my friend Liz Was (by then known as Lyx Ish, but born as Elizabeth Nasaw) died.

She, too, was sick, but also too too young to leave us so soon.

I felt the weight of that death too, even thought I had met Liz only once. She was full of life and friendliness, a joy to be around.

And she was always kind in the mails, always saying kind things about my work.

She was a maker, a poet, and a visual poet I admired for the beauty and originality of her visual poetry.

I'm sorry to have lost her art, the art she didn't have the chance to write. But I am also sorry to have lost her from the earth. And fart too soon.

Leap days are sad days for me for they remind me of deaths, or losses, of hopes not fulfilled.

I remember today these two women, always beautiful (my aunt said no-one had told her that she was beautiful when she was young, but she certainly was), always friendly, always ready to help a person.

My memories out to those of you who knew these women and what it meant to have them among us.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 29, 2012 20:50

February 28, 2012

Orphic and Orchid

On Saturday, February 25th, 2012, I accompanied my friend Anne Gorrick to a staged reading of Robert Kelly's verse play, "Monologues for Orpheus." Our friend Lynne Behrendt performed in it as part of the chorus, a chorus that didn't speak in unison, but in conversation and in conflict with each other. It ended up being a surprisingly enjoyable evening.

After a few sonorous remarks from Robert Kelly, giving both the modern and ancient Greek forms of one word and explaining that "carmen" means "poem" in Latin (hey, I'm a visual poet, so how could I be one without knowing what a carmen figuratum is?), the evening moved into bassoon.

The bassoon, despite its perjorative nickname (the clown of the orchestra), is a beautiful instrument, both visually and aurally. It has a richness and depth that reminds me of a dark yet smooth Chinese black tea, like the Panyang I had on Sunday afternoon after this performance. The bassoonist, David Adam Nagy, did a great job, not quite perfect, but a performance good enough to wake me to the promise of the day in the evening of it. And he moved, almost like a rock musician (or Pan playing the flute) through his performances of Johann Sebastian Bach's "Allemande" from the "Partita for Solo Flute in A Minor" and of Elisha Adrienne's quite wonderful "Hellenistic Songs," with the tenor voice of Péter Laki thrown in.

After this extravagantly beautiful opening, in the small chapel that is Bard Hall on the campus of Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, we moved into the reading.

The actors were arranged on chairs, with music stands before them to hold the scripts. Orpheus was dressed in a white shirt, the four members of the chorus were dressed all in black, and Eurydice, who also was "the director," wore a grey dress, and she didn't stay in place. Stood by a chair in the corner but moved into the realm of the other actors and danced, slowly, among them. She was the only actor who remained silent the entire time.

The staging itself was remarkable, given that it was a staged reading where only one actor, the dancer, did any moving on her feet. There was something reserved yet affecting about watching and listening to the actor's read their lines in situ, especially since each actor was so remarkably different from each other, so given over to a personality apparently chosen for him or her by Robert Kelly himself. Mikhail Horowitz was dramatic, talkative, expressive, and Lynn Behrendt was reserved, ironic, questioning.

The words themselves were sometimes goofy and obvious and sometimes verging on the sexist. And they were about writing, about the role of the poet in the world, about the responsibility of the poet, but also about the poet's arrogance. Orpheus was the poet, and he sat the most still of all the actors, secure in his beauty and stature, secure in the power and fertility of his orchids.

In the end, I still enjoyed the production. The script needs editing, and maybe I'm disturbed by a play so focused on the occupation of the poet, a play so Narcissistic in its focus. For us poets, there is something interesting in the metaphysical consideration of poetry and the act of the poet in the making of that poetry. But is there a concomitant interest in such in the general audience for such a play? Or is such a work of art intended only for practitioners of its creation?

I wondered, in the end, about the fragility of the poet's status in the real world, the one of flesh and blood and Mammon. I wondered about the conversations we conduct about our art but among ourselves alone. I wondered if we were nothing but Narcissus and Echo ourselves. If we were nothing but automythologists. If we were doomed to watch and listen only to ourselves forever.

But listen:

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 28, 2012 20:11

February 27, 2012

3 Readers, 3 Voices, 3 Words

Ceiling at the Social Justice Center, Albany, New York (24 February 2012)

Ceiling at the Social Justice Center, Albany, New York (24 February 2012)On the night of Friday, February 24th, 2012, I attended dinner at Matthew Klane's house in Albany, and I knew how to drive there because I had become lost in his neighborhood only a few days before, which had made me late for a meeting. So one piece of bad luck turned fortuitous in the end.

The reason I was at his house (for a spectacular vegetarian meal—oh, those latkes...) was to have a small celebration prior to the second of the year's readings in the Yes! Reading and Performance Series, run by James Belflower and Matthew in Albany, New York. Afterwards, I drove to the Social Justice Center, with my friend Anne Gorrick following, and I thought to myself, "Maybe this road will go through to Madison Avenue." But it didn't. It went into a McDonald's parking lot. Anne followed me, honking at me as we turned around. And that's when I remembered that I had once before tried this same trick, and come to this same unfortunate end.

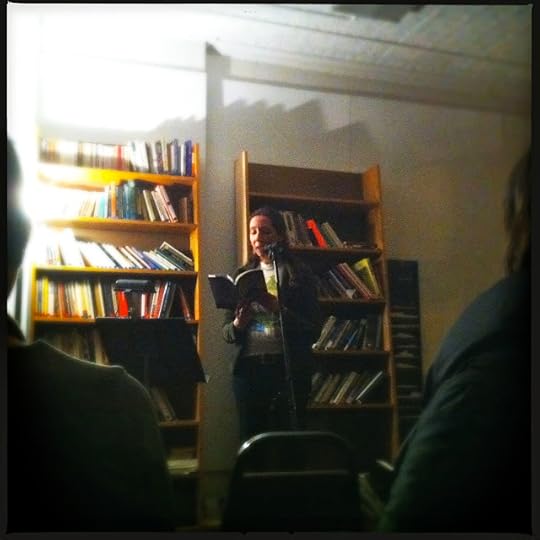

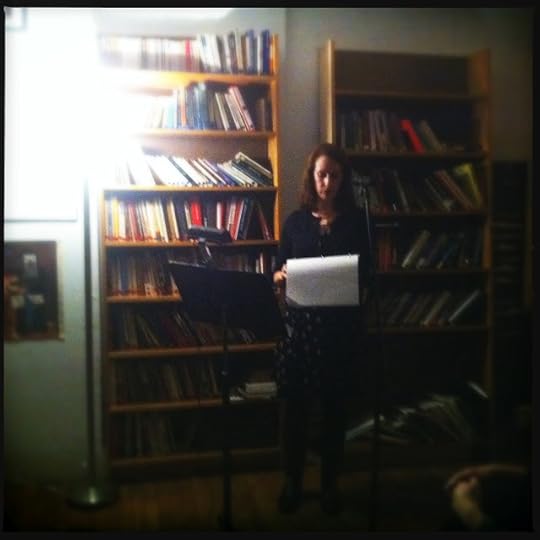

Julianna Spallholz

Julianna SpallholzThe Social Justice Center is not much to look at, except that I enjoy looking at it, even its ceiling. And there was a good crowd there last Friday, about thirty people in total. Matthew and James shared the emceeing, and one of my favorite parts is hearing the collage poems they create out of their readers' works. First up was Julianna Spallholz, a writer of short fiction, reading from her book The State of Kansas.

She began with a short-short story (old term, I know) with a punchline, which was a good opening for the audience. She then read a much longer, but still short, work. She identified the first story as autobiographical ("True story," she appended), but the other seemed so as well. The stories worked poetically more than narratively. They exhibited almost no narrative or character development (they happened, if I can use that term, in such small spaces of time that the latter would have been nearly impossible. They functioned essentially as dramatic monlogs, maybe still lifes. And she read these with an actor's voice, giving meaning to the words.

And "giving meaning to the words" was the them of the night, and (I'll note) the real reason to go to a reading.

NF Huth

NF HuthNext up was Nancy, NF Huth by her poet's name. She read from two of her recent books, first her chapbook, "3 Words," reading a few poems from it. These poems are based on structural repetitions that change throughout the poems: repetitions of words, repetitions of sounds, repetitions of phrasal structures. And this complex set of repetitions actually represents, in a stylized form, the current speech patterns of her mother. These are beautiful surprising poems, well read, and starting with these for the first time in a reading was a good entryway, again, into her work.

She ended with a few poems from her book Radiator. These are poems I know quite well, poems I've read and heard many times, but every time I hear them, I hear new resonances and meanings deep inside their constructed complexities. These seem like simple poems, generally using simple, but decidedly muscular words, but they are quite complex, depending on multitudes of associations and an dramatically indirect method of telling. She read these with serious emotion and to good effect. The audience was entirely with her during the reading, especially with the most powerful reading she'd ever given of her poem "clank."

NF Huth reads her poem "When Dot Wonder" from her chapbook "3 Words" in the Yes! Reading and Performance Series held at the Social Justice Center in Albany, New York, on 24 February 2012.

Lori Anderson Moseman

Lori Anderson MosemanThe final reader was Lori Anderson Moseman, who read a number of poems from her book All Steel. Her poems almost all functioned as catalog poems, list poems, though they weren't quite that. They take words out of the world, though, and line them out for us to see. And she read these with great verve and grace, finding the beauty even in mechanical found language, and playing with language with a ferocity that was both beguiling and pleasurable. Of course, I couldn't quite keep up with them. I'm an aural person, but not for meaning; for meaning, I'm visual, so some of the meaning got away from me, but not the life, the liveliness of the poems.

And, in the end, I thought that Nancy and Lori had many similarities—not in their poems, which were almost diametrically opposed to one another (they were so different stylistically), but in their presences, in the resonances of their voices, in their posture, and the solid placement of their feet on the earth.

It was, all in all, a great night of readings, and it served as a book launch for the three main books these writers read from. I also recorded all of it, so you can lean back in a chair, close your eyes, imagine you are sitting in a darkened room in Albany, New York. And listen.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 27, 2012 20:29

February 26, 2012

Fire, Water, Blood, and Death

They have

no hunger but they

want to kill

What blood is

there in it

for any of

them? and why

do they want

what they

want? Don't

drink the

water

even if you are

thirsty

From the water

it comes

into

you

and then

your life is

killing

You will burn

your

wife and your son

You will

set them ablaze

just to watch

You will hunt

through piles of

dead bodies

for the living one

to kill

Or you will

be

the one running

the one running

away

Attacked with

bone saw

with

gun

with knife with

spading fork

with desire

to kill

for no

reason but desire

to kill

and

kill again

All that saves

you

is how quickly they die

Their

bodies given over

to the disease

that kills them

They do not

know why

they kill

but they

kill

to fill

the time until

they are killed

themselves

Until they

are killed

by water

through their

bodies

or until

you kill them

yourself

Because the only way to

live is to kill

and give

your body over

to the spilling

of blood

which washes

over you

like light

like water

like forgiveness

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 26, 2012 19:18

Mnemnory and Vission

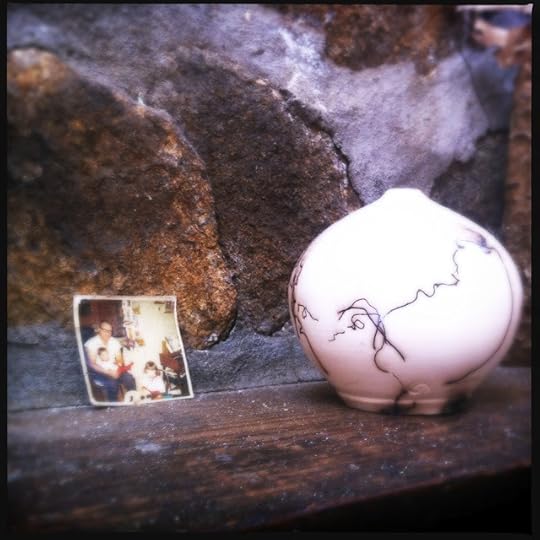

This is Not My Photograph, This is Not My Vase, This is Not My Mantle, This is My Photograph of Them

This is Not My Photograph, This is Not My Vase, This is Not My Mantle, This is My Photograph of ThemAlthough Anne Gorrick and I sat at her kitchen table this morning and spoke of the fact that our poetry is never specifically about anything

Anne Gorrick: I don't think I could write something that was so much about something.

Geof Huth: That was one of its drawbacks, you know.

Anne Gorrick: I know.

Peter Genovese: You mean, writing something about something?

and although we all laughed when her husband pointed out the absurdity of our statements (in the real world, that is), poets are still usually burdened with themes that suffuse their work, often from beginning to end. Creation is the act of making something new, but it is always working from materials that are eons in age, no matter the kind of creation you imagine.

And my poetry is directed by two concerns: memory and how it fails us, and human perception and communication, which serve as the means of collecting and transmitting memory, and how these fail us as well. It is likely that I am an archivist and a writer because I know that we cannot depend on memory. I know that thoughts must be written down to be preserved, and reviewed again and again to remember them as they truly are (and were). I am always amused that records can be used in court cases only as an exception to the hearsay rule, personal testimony of witnesses being assumed to be the best form of evidence. When it is the worst.

My interest in memory derives from the fact that my memory is not as good as it should be. I believe that I've trained myself not to remember too well. I forget people's names because I lived the first part of my life moving every eighteen months or so (even living once on three continents in the course of a single year), so the remembering of names was a waste of brain power. I put most people's names in what Apple used to call its computer's volatile memory. Similarly, I have wiped bad experiences out of my memory, or dulled them sufficiently so that I might not feel them anymore. One time even, years ago, I suddenly recalled a series of events from my childhood, and I was surprised by this memory and certain of its reality because it was stitched into the fabric of everything else in my life in Little Barn or Barbados. I had intentionally, even if subconsciously, erased it.

Memory is a slippery beast built out of experience but mixed with other memories, with assumptions, with unintentional "corrections," with voids. As time extends towards our individual deaths, we hold less and less firmly onto these memories, whether our minds hold their own sharpness or not, and the memories because airier, filled more and more with nothing.

And that is why Mnemosyne is my muse, though she is actually the mother of the Muses. And Mnemosyne gives poets that power to speak, maybe because we need to remember at least a few facts to have the means of speaking and the means of making. Because of Mnemosyne (whose name we recall mnemonically), I see memory (the word) as mnemnory, remembered but not, pronounced but silent.

I have spent many weeks now in the active practice of remembering, which is more a creative act than we imagine it to be, and so memory is on, and always in, my mind. But I've also been immersed, just a bit more deeply than usual, in thoughts about signs, the signs (visual and verbal, gestural and facial, sonic and tonic) we exchange with one another, and with thoughts on how we perceive them.

The usual but expanded reason for this interest in signs is that I have been wrawing poems, with pen, into sheets of copper. The creations I make are larger than but bear a familial resemblance to my fidgetglyphs, small visual poetic doodles. But the copper sometimes stops my hand and is a little less forgiving and more directive than paper. This means that my hand is slowed, so my mind is forced to slow as well to keep from overtaking the hand. In turn, that slowing of the mind and the body has forced me to question that entire enterprise of making. I always have. I like to work by hand and to make letters in different forms, to examine the extent of distortion that can be wrought upon a letter and still allow for its legibility, but I continue to question, and question now more deeply, to what degree the visual form of text, even if decorated with images in a similar style, can increase the meaningfulness, the message, of a poem. I know it does. I just don't know if I'm wasting my time doing it.

I've also noticed that people sometimes misinterpret my signs, the poems I write. This is all fine with me because it feeds into the polysemy of the word, and of the poem itself, because it feeds into the idea that ambiguity is a goal of poetry, that pure unalloyed fact and statement are not the province of poetry. Still, some people also don't attempt to read some of my visual poems that are intended to be read, and this is a kind of misreading of the visual poem as a purely visual device, just as someone might read unkindness into the near-constant irony of my speech (and sometimes of my writing).

So I have begun to see more of my signs misinterpreted, which is an enrichment of them, but which is also more evidence of the failure of signs to mean as intended.

Yet there is something else going on. For the last couple of weeks, I have had two small visual defects appear in my vision, not frequently, but regularly. The first is the most befuddling: ever more frequently, I am misreading signs, actual signs out it the capitalist viewshed. As Anne was driving me around Ulster and Dutchess counties, on opposing sides of the Hudson, this weekend, I would tell her how at first glance I was misreading signs. This morning as she drove me to the bus station in Kingston, I conflated two words into one, replacing letters in the second word with the n in the middle of and the t near then end of the first word. I have not kept track of the details of these misseeings, so I don't know exactly how they are working, or if there is some message in the distortions I am wreaking upon the language.

To some degree, this set of errors is merely the product of my being a trained reader, so I read not individual letters but entire words in a millisecond. Sometimes, the first assumption is not the accurate one. This will happen to a good reader from time to time, and it is the equivalent to the errors I make while writing. I type so quickly that I often substitute the word I mean with a strange quasi-homophone of it. I do appreciate these errors and the messages they send us about the limits of our means of communication, the massive possibility for miscommunication that exists between all of us.

My other visual issue, however, is purely physical. From time to time, maybe once or twice a week, my eyes flicker. Maybe it is just my eyelids, maybe it is my eyes themselves pulsing quickly, I do not know, but I am overcome with a strange disquieting tic lasting a few seconds. As this occurs, my vision is affected, becoming jerky, unstable, and unclear, jittery. Through all of this I can see, but I hardly pay attention to, what I am seeing, so I hardly see at all. Instead, I perceive clearly only the disturbances at the slits of my eyes.

A few years ago, a European surrealist died, and the main focus of his obituaries was on his dementia, particularly a statement that he had made about it, something about how appropriate it was for him, as a surrealist, to suffer from dementia. Similarly, I have to say that the tricks of memory in my life and the tricks of my vision occurring now are quite appropriate happenings in my life as a person guided by concerns for memory, communication, and interpretation. We get what we bought.

These few thoughts have reminded me of an important term in my esthetics: rememory, which is a memory of a memory, a memory that was never your own, that was given to you by someone else, but which inhabits you just as your own faulty memories do, that haunts you as your own do, that bides its time until you need it for something. One of my favorite rememories is one of my father's. It was a recollection of his first memory, the memory that went back as far as he estimated his memories did. It was the memory of being carried by his father on a cold day, a day so cold that his father placed under his own coat my father and closed the coat to keep my father warm. Then he opened the flap of the coat to look down at my father, his first and only son, who himself looked up at his own father.

I find this rememory comforting. It reminds us of the importance of family, of people, of being cared by someone who loves you, of being protected and kept warm. It sits in my mind as an antidote to whatever goes wrong in a life.

And I know full well that I may not have remembered the story of this memory accurately at all.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 26, 2012 13:55