Mnemnory and Vission

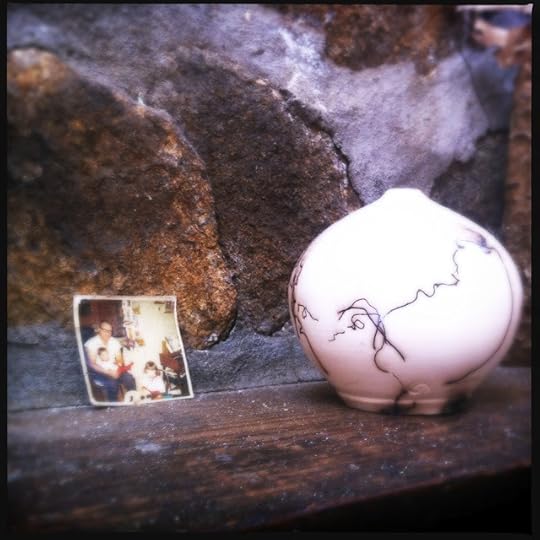

This is Not My Photograph, This is Not My Vase, This is Not My Mantle, This is My Photograph of Them

This is Not My Photograph, This is Not My Vase, This is Not My Mantle, This is My Photograph of ThemAlthough Anne Gorrick and I sat at her kitchen table this morning and spoke of the fact that our poetry is never specifically about anything

Anne Gorrick: I don't think I could write something that was so much about something.

Geof Huth: That was one of its drawbacks, you know.

Anne Gorrick: I know.

Peter Genovese: You mean, writing something about something?

and although we all laughed when her husband pointed out the absurdity of our statements (in the real world, that is), poets are still usually burdened with themes that suffuse their work, often from beginning to end. Creation is the act of making something new, but it is always working from materials that are eons in age, no matter the kind of creation you imagine.

And my poetry is directed by two concerns: memory and how it fails us, and human perception and communication, which serve as the means of collecting and transmitting memory, and how these fail us as well. It is likely that I am an archivist and a writer because I know that we cannot depend on memory. I know that thoughts must be written down to be preserved, and reviewed again and again to remember them as they truly are (and were). I am always amused that records can be used in court cases only as an exception to the hearsay rule, personal testimony of witnesses being assumed to be the best form of evidence. When it is the worst.

My interest in memory derives from the fact that my memory is not as good as it should be. I believe that I've trained myself not to remember too well. I forget people's names because I lived the first part of my life moving every eighteen months or so (even living once on three continents in the course of a single year), so the remembering of names was a waste of brain power. I put most people's names in what Apple used to call its computer's volatile memory. Similarly, I have wiped bad experiences out of my memory, or dulled them sufficiently so that I might not feel them anymore. One time even, years ago, I suddenly recalled a series of events from my childhood, and I was surprised by this memory and certain of its reality because it was stitched into the fabric of everything else in my life in Little Barn or Barbados. I had intentionally, even if subconsciously, erased it.

Memory is a slippery beast built out of experience but mixed with other memories, with assumptions, with unintentional "corrections," with voids. As time extends towards our individual deaths, we hold less and less firmly onto these memories, whether our minds hold their own sharpness or not, and the memories because airier, filled more and more with nothing.

And that is why Mnemosyne is my muse, though she is actually the mother of the Muses. And Mnemosyne gives poets that power to speak, maybe because we need to remember at least a few facts to have the means of speaking and the means of making. Because of Mnemosyne (whose name we recall mnemonically), I see memory (the word) as mnemnory, remembered but not, pronounced but silent.

I have spent many weeks now in the active practice of remembering, which is more a creative act than we imagine it to be, and so memory is on, and always in, my mind. But I've also been immersed, just a bit more deeply than usual, in thoughts about signs, the signs (visual and verbal, gestural and facial, sonic and tonic) we exchange with one another, and with thoughts on how we perceive them.

The usual but expanded reason for this interest in signs is that I have been wrawing poems, with pen, into sheets of copper. The creations I make are larger than but bear a familial resemblance to my fidgetglyphs, small visual poetic doodles. But the copper sometimes stops my hand and is a little less forgiving and more directive than paper. This means that my hand is slowed, so my mind is forced to slow as well to keep from overtaking the hand. In turn, that slowing of the mind and the body has forced me to question that entire enterprise of making. I always have. I like to work by hand and to make letters in different forms, to examine the extent of distortion that can be wrought upon a letter and still allow for its legibility, but I continue to question, and question now more deeply, to what degree the visual form of text, even if decorated with images in a similar style, can increase the meaningfulness, the message, of a poem. I know it does. I just don't know if I'm wasting my time doing it.

I've also noticed that people sometimes misinterpret my signs, the poems I write. This is all fine with me because it feeds into the polysemy of the word, and of the poem itself, because it feeds into the idea that ambiguity is a goal of poetry, that pure unalloyed fact and statement are not the province of poetry. Still, some people also don't attempt to read some of my visual poems that are intended to be read, and this is a kind of misreading of the visual poem as a purely visual device, just as someone might read unkindness into the near-constant irony of my speech (and sometimes of my writing).

So I have begun to see more of my signs misinterpreted, which is an enrichment of them, but which is also more evidence of the failure of signs to mean as intended.

Yet there is something else going on. For the last couple of weeks, I have had two small visual defects appear in my vision, not frequently, but regularly. The first is the most befuddling: ever more frequently, I am misreading signs, actual signs out it the capitalist viewshed. As Anne was driving me around Ulster and Dutchess counties, on opposing sides of the Hudson, this weekend, I would tell her how at first glance I was misreading signs. This morning as she drove me to the bus station in Kingston, I conflated two words into one, replacing letters in the second word with the n in the middle of and the t near then end of the first word. I have not kept track of the details of these misseeings, so I don't know exactly how they are working, or if there is some message in the distortions I am wreaking upon the language.

To some degree, this set of errors is merely the product of my being a trained reader, so I read not individual letters but entire words in a millisecond. Sometimes, the first assumption is not the accurate one. This will happen to a good reader from time to time, and it is the equivalent to the errors I make while writing. I type so quickly that I often substitute the word I mean with a strange quasi-homophone of it. I do appreciate these errors and the messages they send us about the limits of our means of communication, the massive possibility for miscommunication that exists between all of us.

My other visual issue, however, is purely physical. From time to time, maybe once or twice a week, my eyes flicker. Maybe it is just my eyelids, maybe it is my eyes themselves pulsing quickly, I do not know, but I am overcome with a strange disquieting tic lasting a few seconds. As this occurs, my vision is affected, becoming jerky, unstable, and unclear, jittery. Through all of this I can see, but I hardly pay attention to, what I am seeing, so I hardly see at all. Instead, I perceive clearly only the disturbances at the slits of my eyes.

A few years ago, a European surrealist died, and the main focus of his obituaries was on his dementia, particularly a statement that he had made about it, something about how appropriate it was for him, as a surrealist, to suffer from dementia. Similarly, I have to say that the tricks of memory in my life and the tricks of my vision occurring now are quite appropriate happenings in my life as a person guided by concerns for memory, communication, and interpretation. We get what we bought.

These few thoughts have reminded me of an important term in my esthetics: rememory, which is a memory of a memory, a memory that was never your own, that was given to you by someone else, but which inhabits you just as your own faulty memories do, that haunts you as your own do, that bides its time until you need it for something. One of my favorite rememories is one of my father's. It was a recollection of his first memory, the memory that went back as far as he estimated his memories did. It was the memory of being carried by his father on a cold day, a day so cold that his father placed under his own coat my father and closed the coat to keep my father warm. Then he opened the flap of the coat to look down at my father, his first and only son, who himself looked up at his own father.

I find this rememory comforting. It reminds us of the importance of family, of people, of being cared by someone who loves you, of being protected and kept warm. It sits in my mind as an antidote to whatever goes wrong in a life.

And I know full well that I may not have remembered the story of this memory accurately at all.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 26, 2012 13:55

No comments have been added yet.