Geof Huth's Blog, page 17

January 30, 2012

What I Is

I have had in my position for a few years now a small and fragile piece I-shaped wood found in floor of probably the largest building in Dreamtime Village in West Lima, Wisconsin. In the floor of this building there were a number of other I's in the floor, but I picked this one essentially at random. Sometime over the years a small piece of this had disappeared, but I kept the I, as a memory of a visit to see mIEKAL aND and CamillE Bacos, as a memory of a few short days' respite from my regular life, and a memory of my only real vacation in many years.

But I picked up the piece of wood, the piece of word, so that I could fashion some kind of object poem out of it. When I do such, I have only vague ideas what I will eventually do with the object, and those ideas usually coincide with the reality I produce only more vaguely. I wait for some kind of inspiration, and when that comes I finally make the piece.

That inspiration came on Saturday, January 28th, two days ago. While I looked at the piece of wood (a piece of the word "I") on a window sill, I devised the entire text of the poem ("the litt/lest part of I"). This came to me all at once, as if thought out in advance, except that I decide, after about a second, to split the word "littlest" into two for two reasons: two increase the meaning and to allow the word to fit across the narrow width of the I.

Almost immediately, I began a search for my diecut metal letters and a hammer, and within an hour I was stamping the letters into the wood and then painting it with watercolors. Because the watercolors needed to dry, the painting (followed by the recoloring in of the letters so that they would remain visible) took and extra day, and I finished the process yesterday, Sunday, January 29th.

The little video above shows the entire poem and include a brief explanation of the genesis and meaning of the poem.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 30, 2012 21:00

January 29, 2012

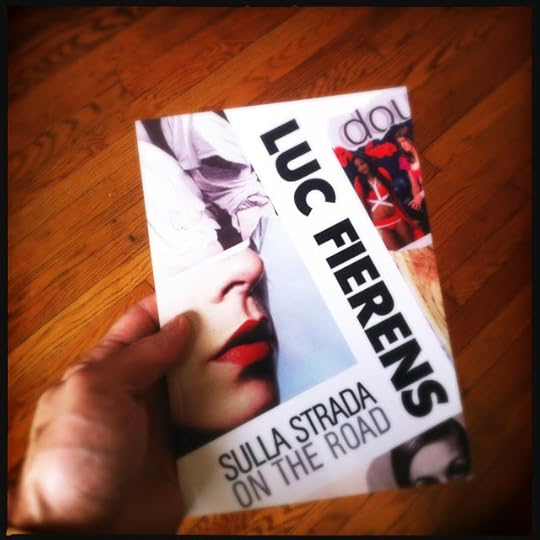

Une collagiste pour nôtre temps

Luc Fierens ended last year with a short but significant exhibition of his works entitled "Sulla Strada [On the Road]—Luc Fierens" at the U Man /Contemporary /Art /Space /Project in Marano d'Isera, Trento, Italy. This exhibition covered Luc's career as a visual poet and collagist from 1984 through last year, and the catalog of the exhibition presents these in chronological order, which allows us to see how Luc's style progress from a fairly rough-hewn one to a style almost as polished as the glossy advertisements that became the main source of fodder for his poems.

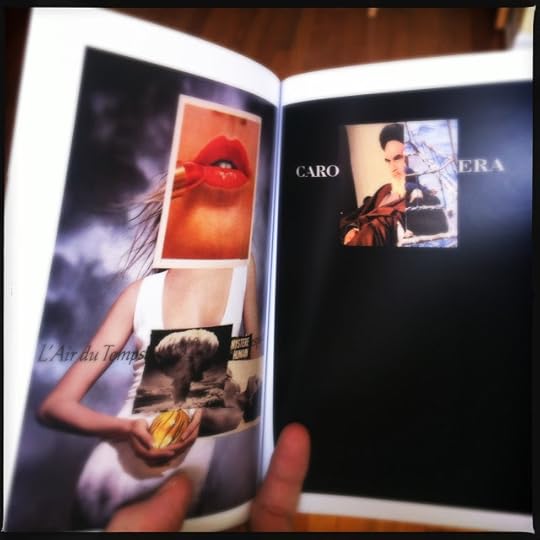

Luc is an artist for the world, so his works are "written" in English, French, Flemish, Italian, German, and even wordless. And certainly combinations of the above. His poetry is the poetry of appropriation and anti-approbation. Often his poems focus on the the subjugation of the populace through the power of commercialism. This is most evident with his works using the feminine form, sometimes sexualized, to show the contemporary woman's fate, in the hands of commerce, to be objectified, sexualized, starved, controlled, and made mute. Often in one of Luc's collages, a woman's mouth is covered or removed. She may be spoken to, but she cannot speak.

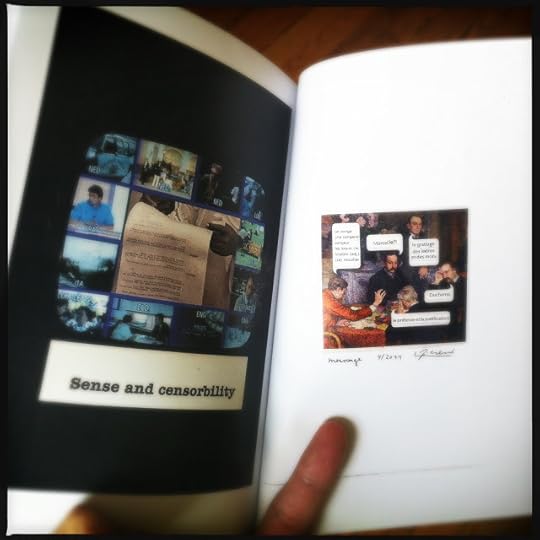

So his poetry is often political, but it is also humorous, as in a table of four gentlemen discuss the meaning of art, the making of art, the meaning of language, the way a dreamer dreams himself into being and scratches out the words to make any of the sense they need.

His poems are about the human mystery of our times, where we are filled with hope and abundance and despair, and terror at the possibilities we have devised. And ours was, if I'm reading the second poem above correct as being in Spanish, an expensive era, one that cost us dearly, because if Mammon didn't get you then all manner of believers would. For the believers are the most dangerous of us all.

Luc is a poet. He may hide himself as an artist, but that is only the shape he takes to make these poems, and I think they are important because they are about the process of living and making sense in a world increasingly complex and increasingly focused on money. And I think they are important because he has that collagist's eye that allows him to take disparate images and words and patch them together into a whole world, one both dazzlingly beautiful and horrific, and at exactly the same time, in exactly the same place.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 29, 2012 20:33

January 28, 2012

3 Movies, 1 Day

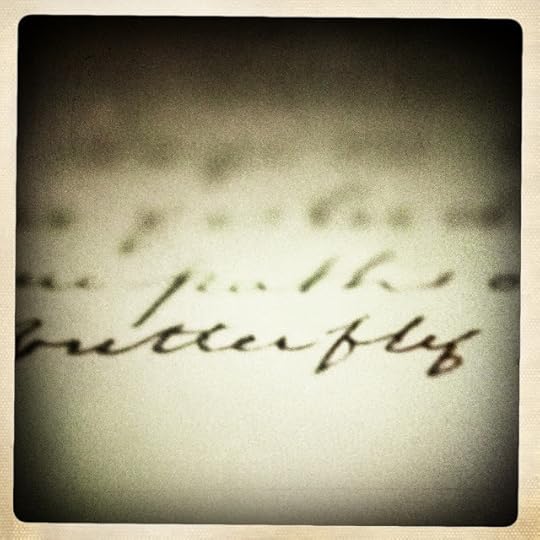

The Word "butterfly" in a Letter from John Keats to Fanny Brawn in the Film Bright Star (2009)

The Word "butterfly" in a Letter from John Keats to Fanny Brawn in the Film Bright Star (2009)The most important literary theorist for my poetics isn't Derrida or Foucault, not even Barthes (though one might imagine that being so). Instead, the literary theorist who guides me most is the one no-one thinks of: St Augustine. Or Augustine of Hippo, if you prefer, the Christian philosopher who gave up his Christianity in his youth, to pursue a life of uninhibited pleasure, only to return to the Church and become one of its great theologians. But also a philosopher, and a philosopher interested in the transmission of meaning. It is that last bit alone that makes him my literary theorist.

St Augustine posited the then-radical notion that the relationship between the signifier and the signified was an arbitrary one, that there was nothing natural in the practice of language assigning names to things, nor in assigning letters to stand in for the parts of the names themselves. Beyond this, he made a distinction between two kinds of signs: signs in space and signs in time. Signs in space consist or writing and images. They take up space, they inhabit space, and they are distinguished by their stillness and the fact that the percipient can take as long as is need to wend a way through to the end of the signs—just as some people can read a 400-page novel in a couple of hours but others will require a week's time. Signs in time Augustine would have identified as speech and singing. In this case, the percipient must keep up with the speed of the sign, because the sign does not exists in space, but in time; it moves, and we must keep up with it in order to understand it.

Although Augustine could not have imagined it, a movie is actually a sign in time. It may be made of images and include text, but all of that is moving, in motion. We have to wait for it, listen to it, watch it, to catch it, to understand it.

The first film: Bright Star (2009)

It seems, however, that we have made it to an age where a film is not quite a sign in space, but it closer to a book now than it once was. Last night, I began watching Jane Campion's Bright Star on line, but I grew tired and, uncharacteristically, headed to sleep a couple of hours before midnight, pausing in the middle of the film. When I awoke this morning, just after 6 am (even though it is a Saturday), I began watching the film right where I had left off, in the middle of a sentence being spoken by John Keats. I could stop the film as if it were a book I'd slipped a bookmark into; I had some small ability to control the way the film was a sign in time. Soon, I grew weary again, maybe from not eating a breakfast, so I paused the film and slept almost until noon. Once I awoke again, I clicked the computer resting by the couch and began the film again, ending it an hour later, after pausing it to allow myself time to carry out various chores.

The three films I saw differed so much from one another as to seem from different genera, not merely different species. Jane Campion is a great director and was from the start with The Piano. She has an eye that is careful, imaginative, but never outrageous. She surprises us with perspective, rather than the craning of the neck of the camera or acrobatics of any kind. But she is patient, and more patient, I gather, than most filmgoers. She tells a story slowly, meaning that every frame does not need to be the telling of the story; frame after frame is merely vision. We are allowed to see. We are given the time we need to see everything in the frame, even if all that happens is that a diaphanous curtain is curling into a room with the wind.

And her story of John Keats is as Romantic as his poetry, as, I suppose, his life itself, for what poet had more a cliché'd Romantic life than Keats? He lived and died believing he was destitute, never realizing he well off from money left him by his parents. He was sickly, dying of tuberculosis in Rome, and wrote poetry as if it were his only passion. Poor, sickly, and lovesick to Fanny Brawn, he died in his youth, believing himself a failure as a poet, only to become a major poet after his death. What could be more Romantic than that? Maybe only the poetic suicide.

I think, maybe, Campion's telling of the story can, for a film is always a simplification of a complexity. Trapped in time, a film must cut the story short, remove the details, cut to the chase. If the filmmaker is also one to tell a story slowly, then she will reduce the story even more. And she may enhance the story but ending it with bits of text that tell us that Fanny never removed the ring Keats gave her, never recovering from his death. But Campione failed to tell us of Fanny's later marriage, of her her children, of her long life.

Even though that long life, extending much more than twice the length of Keats' own, might actually be the more Romantic telling.

The second film: The Artist (2011)

My daughter and son-in-law work in the moving-image media (she in television and he as an editor of commercials—and don't talk to me about the likelihood of their moving to Los Angeles this year; sure, California is my native state, but it's too far from me), so they always know anything there is to know about a film nominated for an Oscar. I, however, heard of The Artist only when it was nominated, and I had no idea what it was about until this afternoon. After reading that it was a "silent" film—more about the quotation marks later—I decided to attend a mid-afternoon showing alone.

I walked to a 3:45 showing that was inhabited almost entirely by people over 60 years old, still people much too young to be around for the heyday of silent films. The film is not completely a "silent" film: two scenes include the sound of objects and voices. One sequence is a dream in which the sounds of everyday objects falling, and of laughter, are strange and surprising. These sounds are so jarrring because the dreamer, who is the main character of the movie (George Valentin, a silent film star being left behind as films transition to talkies) expects his dreams to mimic his movies. (After all, dreams are a kind of movie. That is why I call all transcripts I make of my own "dreamovies.") And the second sequence is the last sequence of the movie, the only one in which we hear the real voices of the actors. This sequence ends with a wonderful little dance number in which Valentin looks just like Gene Kelly. When we hear the dreamer's voice, we are not surprised, because we know what killed the silent film stars who didn't transition to the new world of cinema.

Although the filming of The Artist was totally different from that of Bright Star, both have beautiful cinematography appropriate to the vision of the films they are. Michel Hazanavicius, the director of The Artist, films, necessarily, in black and white, which reminds us, for those of us who might have forgotten, just how beautiful black and white can be, with its panoply of greys. There is a resonance to every frame of this film, a radiance that is rare with color. But Hazanavicius is, also, an imaginative framer of scenes. Although these are usually done with restrained grace, there is one shot that stands out for its expressive beauty, and the insistence of it.

George Valentin, taken to drink, is sitting at a bar, the surface of which is a mirror. From our starting viewpoint, itself a bit canted, the "real" image of Valentin is oriented just about properly and the mirror image of him is upside down. But the camera begins to rotate, and our viewpoint is, eventually, turned around: the mirrored Valentin is now the one properly oriented, and the "real" Valentin, upset at his fate, dumps his transparent liquor onto the bar. For a moment, but only for a moment, the image of Valentin is obscured by the moving liquid, but almost immediately the puddle of alcohol stills, becomes itself a mirror, and we see, once again, the sullen image of George Valentin, staring down into his liquid fate.

The Artist is an accomplished film, and the two stars are radiant and perfect. Also, I was also moved by the way in which the film altered, just slightly enough, the unrestrained acting style of silent films to make the "reality" we see a bit more moving because a bit more real. These are actors who know that their bodies, particularly their faces, are the signs in time we require most to make meaning of this film. Still, I wonder, if making a black and white silent film, no matter how beautifully shot, no matter how well acted, makes sense nowadays, just as I do not know if it makes sense to write accentual-syllabic rhyming verse these days, as I sometimes do:

Sonnet for Sleep

Thenights afford us weariness and dreams,

Sothat we might abandon day's dominion,

Tolead our quiet, simple lives through streams

Ofsadness, toil, and ritual communion.

Thesights we see are nothing more than dull

Andtempt us hourly with thoughts of wine and gold;

Ifbut that hour could blossom rich and full,

Wemight die happy 'fore we e'er turn old.

Thefrights we live encourage us to sleep:

Myriaddead, their screaming, and their yelps,

Wecannot hope to find a way to keep

Theirpain subdued, or e'en a drug that helps.

Twomore lines and then this poem is done,

Andthen the world of humans I can shun.

But what truly amazed me what how unsilent this film was, how unsilent most "silent" films were. We needed the avant-garde filmmakers, like Stan Brakhage, to show us what a real silent film was. The "silent" film I saw today was the one the most filled with sound. Music accompanied everything. There was never an instance of silence of any length. The lack of voices was insistently replaced by music, and the score was good: it was foregrounded, but it did not hit the audience over the head, and it was appropriate accompaniment throughout the film, and quite beautiful at times. But it never ended.

Still, there was a problem for me. I had gone to that film in order not to think; I was there so that I could think of nothing but the film, but this film didn't work for we: Without the voices, without my needed to listen to and interpret voices throughout the film, a large part of my mind was open for thoughts, so I thought constantly about my life, that one thing I had come to the film not to have to live through. For all art is escape from the self, be the art film or poetry or painting, which are probably the three most common ways I escape into the serene escape of selfless revelry.

Intermission

Deciding not to make my own dinner tonight, after the movie I walked a few steps to a Vietnamese restaurant and had a wonderful, though solitary, Vietnamese dinner (at exactly the place where I'd had dinner exactly a week before). I began with a salad: grated radish the size of noodles, dried papaya in strips (and, somehow, resembling dried meat in texture and flavor), and a nice spicy sauce. I followed this with a huge and more than hearty phở bò (noodle and beef soup) accompanied by a lotus tea (something like perfumed water, but warm). During the dinner, I considered all the work I had planned to do tonight (including this posting, in a form imagined to be much shorter) and an object poem ("THE LITT LEST") I was working on. I began to wonder when the next showing of Shame was, and it ended up being ten minutes after I had finished paying my bill. So I walked the few steps back to the movie theater and paid a ticket for another film.

The third film: Shame (2011)

I knew a little about this film's NC-17 rating (the equivalent of the original X rating, "adults only"), because I had read the New York Times' review of the movie a couple of months ago. In the film, Michael Fassbender (an actor with an Irish mother and a German father, but whose accent was believably American for almost the entirety of the film but didn't need to be since the character had identified himself as someone who had moved to the US from Ireland in his teens) plays a character named Brandon, who is a massive sex addict.

Once again, the audience in this film was significantly over 60, though not primarily so. What drew me to the film was not the sex, but the obsession. As an obsessive myself (in terms, let's say, of writing and creating), as the grandson of a woman who clearly had all manner of obsessive compulsive disorder, as the son of a man who has lived his life under two separate and not overlapping obsessions (stamp collecting and genealogy—see the connection?), and as the father of a woman who describes herself as having "self-diagnosed OCD," I have a personal interest in the field. But I doubt any of us has the level of uncontrolled obsession that drives Brandon to have sex with multiple women he doesn't know, every day, and then is forced into watching porn on his computer and masturbating.

After watching The Artist, this film was overbearingly quiet at times. The sound of people eating popcorn at the beginning of the movie was painful to me, but I had not noticed that at all while watching the first film. (Actually, even the smell bothered me this time, though it might have been because one of the popcorn eaters was sitting right next to me.) When the post-60 gentleman next to me fell asleep and started breathing through his mouth, I had to force myself to focus on the film. Talkies simply tend to be quieter than silent films, because the music in them doesn't need to be constant.

This was the film that was able to force my own thoughts out of my head. This was the film that could fill my thinking, that could become my imagination. And this was quite a remarkable feat, because the director, Steve McQueen (not the star of The Great Escape) was originally an artist and has a visual artist's perspective. Saying this doesn't mean that I think his shots were more beautiful than those of Campion or Hazanavicius. That is, simply, not the case. But his shots were longer. He didn't play with the camera as much. For many shots, he left the camera perfectly still for minutes and allowed the actors to speak within that space, having them leave the frame and return and leave again and return again. Often, he filmed the movie as if it were a play.

There was something calming in this technique, especially since the film was so frantically sexual, though never erotically so. This was a revelation. Here was a film that shows the protagonist's (sizable) penis more than once, that is filled with nudity and sex acts, yet I found it not ironic at all. Was it, I wondered, because there was not sex act between two people who really knew and connected to each other? (As a matter of fact, Brandon was unable to create an erection—and the man's nickname should have been Priapus—only once: when he truly seemed to know and be attracted to the woman, instead of to the idea of having sex.)

Somehow, this last film, by an artist who desires to be an avant-gardist, is the most proper, at least in terms of just desserts. Keats died for no reason. Valentin is saved from his pride. But Brandon is instead damned to be eaten away by his desires, desires that cannot be quenched. In one of the last scenes, he is having sex with two women, and his need for an orgasm is intense, so intense that he face is a mirror into his pain. He cannot escape himself. And we know he never will.

Coda

Maybe nothing actually holds these films together, but a good thinker can always fabricate a parable out of three fables.

I watched these films—I being only one of thousands of people who likely watched at least one of these films today—and I was able to figure out how the person I am was reflected in the protagonists of each film.

It was painful for me to see Keats, such a wisp of a man. He (but also his friend Mr Brown) was infected by poetry. He was not a practical man, though he gave in to practicalities when he had to. He was not rich enough, or so he thought, to marry Fanny Brawn, who Campion presented to us as his one and pure love. If love is a disease, poetry still might be a greater one, and I can imagine a life sitting and writing poetry throughout the day, as Keats often does in this film, because that is what I do whenever I can.

George Valentin is also driven, though driven not to change. He wants to keep going the film industry that is dying among him. It is as if he is standing among the thousands dying in Atlanta in the middle of Gone with the Wind, but all he can think of is the Tramp walking away from the camera at the end of the movie and twirling his cane. George lives by not accepting help, which works just fine, until he actually needs help. I have live a life of spurning help, so much so that no-one would likely help me if I needed it. Whenever I wonder if I am an American (because it is difficult, I must admit, for a man of my beliefs to live among the multitudes of American believers who believe in reprehensible ways), I force myself to understand that my sense of the necessity of self-reliance leads me inexorably to a rejecting of community, even of family, no matter how important both of those are to me.

Brandon, except for the focus of his obsession (and maybe the destruction it causes) is simply me. Here I sit, late at night, after anyone around me has gone to sleep, writing, and why? Because writing is the only way I can formalize what I believe, writing is the evidence I will leave behind that I had existed, writing is the decorporealization of myself, yet palpably so. And it is not just writing; it is so many ways of making signs: by drawing, by painting, by singing, by writing computer code, by performing, by dancing. All of these means of making are merely extensions of writing for me. I am a poet during all of them. I am a poet through my mere existence. And I do all of this because, just like my friend Lynn Behrendt, just like my wife Nancy, I am a confessional poet. And my confession is, "I exist. I don't know why, I cannot explain how, but I exist, and I will continue to prove it until I exist no longer."

All of which leads inexorably (because everything is inexorable) to the need not to think about oneself. I am so focused on creation that I have to watch things and read things and even smell things so that I can be filled with something else besides myself, so I won't have to be continuously and unremittingly faced by myself. And this is the beauty of going anonymously into the dark to watch the display of light on a giant screen:

We need to escape ourselves. All we need to do is escape ourselves.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 28, 2012 20:40

January 27, 2012

--e- Ee--e-e--

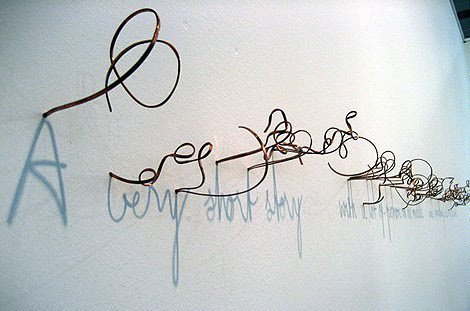

Fred Eederkens, "A very short story"

Fred Eederkens, "A very short story" His name is all e's for vowels and r's in each half. No letter dares to jut below the imaginary line that holds the letters in line, so there is a straightness to it. The name. His name.

But not the art.

It is about twisting and bending, about creating shapes that will write something in shadow upon a plane, a surface flat and plain.

There is a disjunction, a discontinuity, between what we see, its two parts: between the chaotic twistings and the stylish longhand that rests upon the wall. The photograph must be taken from the side to allow us the conflict of sight.

We might not, ourselves, alone, left to our own feeble devices, be able to imagine this text because we live in a three-dimensional world but we see and think in a two-dimensional one.

In our world, there is no understandable connection between the loopings of metal out of the wall and the gentle loping shadow text on the wall.

We cannot understand how the real thing, the hard and fast metal, could not be the focus of our eyes, how the shadow can take such an uncharacteristically prominent role.

How does the static of this twisting metal become a message? How can shadow become ink? Is the message vague and unclear, or perfectly clear in all ways?

Can we tell why the source of the message can be chaos yet the story clear?

Who are we to ask questions?

We are the watchers. The makers make us watch.

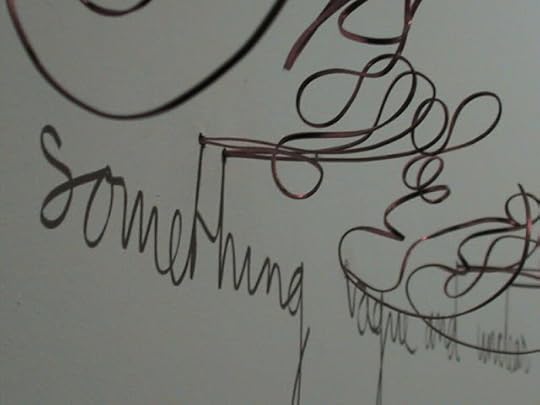

Fred Eerdekens, "Something vague and unclear"

Fred Eerdekens, "Something vague and unclear"

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 27, 2012 19:31

January 26, 2012

I Thought Poets Were People of the Word

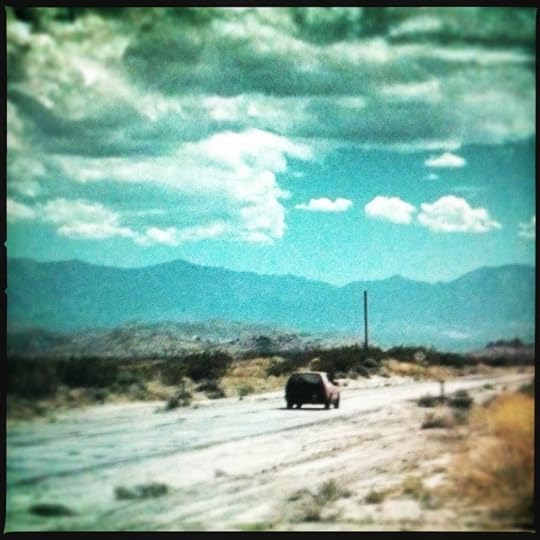

"The Sky is Aqua on Thursday Nights"

"The Sky is Aqua on Thursday Nights"Actually, it was Susana Gardner's comment that started this: her point that mIEKAL aND and I were "the wordmeisters," meaning, I think, not just the stringers of words together, but the makers, the inventors, of words. But it seemed to me that word coinage is merely the most elemental act of poetry, especially the way mIEKAL and I practice it, and that we do this because we are in the thrall of language, slaves to meaning and the flying buttresses of meaning (the sounds and the shapes) that hold it temporarily in place.

So I spoke and recorded a little extemporaneous aural essay today, one that began with the idea and the sentence, "I thought poets were people of the word," but which moved into more general considerations of language before moving to poetry (which is almost a return to the poet). This essay is one of my more rambling aural essays, though also one of the shortest, but it is also one that can't be reproduced on the page. The sound of my voice, and the sound of my voiceless mouth, are essential to the essay.

Listen, if you will. The photograph above I snatched from the film, Wristcutters: A Love Story, while it was playing on my computer, and now the image is all mine. As I say. Appropriation is appropriate.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 26, 2012 20:21

January 25, 2012

The Small Time with Font Boy

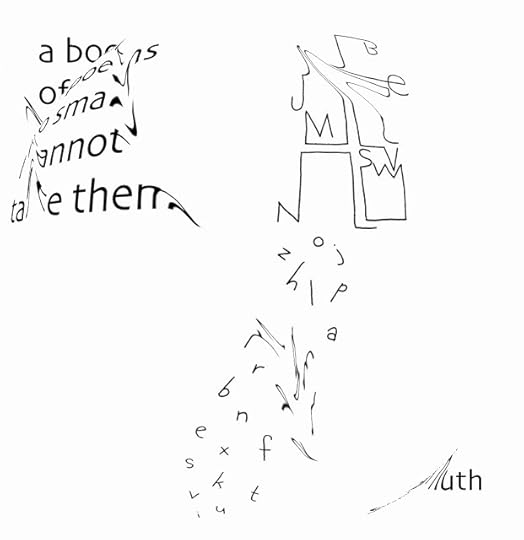

Distorted Version of the Cover to Geof Huth's a book / of poems / so small / I cannot / taste them (2006)

Distorted Version of the Cover to Geof Huth's a book / of poems / so small / I cannot / taste them (2006)I'm writing about reading. The reason is twofold: First, I generally write about only two things: writing and reading. Second, today Goodreads, a social media platform for people to document and communicate about the books they have read, sent me a note that I had to rescue two of the books I had written.

"Rescue" seemed a fairly dramatic term to use, especially since all that was happening was that Goodreads was changing the source of its database of book titles from Amazon.com, which apparently listed these two books, to other sources. Without a link to a database of bibliographic information, any book would essentially disappear from Goodreads. My ratings for them (which were no ratings at all, since I shouldn't rate my own books) would remain, as would my reviews (also nonexistent), but they would be attached to a book without an author's name or a title. Even though Goodreads knew my name and that I was the author (and even though they had ISBNs for each book).

I rescued the books by adding a tiny bit of bibliographic information, including a link to a relevant webpage for the book. After finishing with the second book, Goodreads forwarded me to a page declaring

Great news, all books you have authored are safe. There are 15 books from your bookshelves that need your help:

Now, I could take the time to save two of my books from disappearing from the Goodreads universe, but I hadn't the will to save fifteen other books. Ironically, though probably due to the protocols Goodreads used, the last book I had listed as "read" only a few days ago was at the top of this list: Rae Armantrout's Extremities, one of the books I have recently "reviewed" in this very space.

This reminded me of a couple of small events from my life, one of which was that someone interested in visual poetry friended me the other day through Goodreads, explaining to me afterwards that she did it so that she could see what I read. I explained that only a small fraction of the books I ever read are actually recorded in Goodreads, so the source is mostly holes, so many holes that there seems to be no edge to them.

The books I write are the small time, and even most of the books I read are the small time. This point leads, eventually, to my second thought. To think that Rae Armantrout's book (granted, out of print) could be in need of rescuing meant that I had to wonder what was the hope for the rest of us. Not much.

Back in 1987 or 1988, when I lived in Horseheads, New York (the place where I insisted we live, and only because of its name), I received a note from The Nation explaining that they had a column in their magazine called "The Small Time," focused on such topics as underground literature, and that they might be interested in running a short piece on my micropress dbqp. Most of the publications I published were handmade: each copy of each issue typed or rubberstamped or handwritten or linoleum-block-printed, and all by hand. So I sent off a small package, at my expense, to the magazine, and never heard a word from the place again.

Over the past few days, even before this interesting Goodreads development (or undevelopment), I had remembered that story, so I chewed over it and came to a conclusion: dbqp was too small for the small time. Maybe I could have been small, but by adding "time" to it the concept became too significant to include me. This could have been a sobering thought, if I had ever believed anything else, or wanted something else.

But I like the small time, or the nano time. I am not interested in what people in general are interested in. I know nothing about sports, but I think the Super Bowl (if that is how it's written out) is this weekend. I'm not sure, but I've seen a few signs that suggest that. I've never watched a football game, except ones I've played in at school. When people ask me if I've read certain mystery novels, I say that I'd never read such middlebrow stuff. (Yep, obnoxious, I know. But mystery novels?) No, I have not watched American Idol on TV, and I have no desire to. All of these are of bigger time than most of what I'm interested in.

What I like about the small time is that it is filled with the people I know, even if I rarely see them. I've seen mIEKAL aND only four times, I think, over the course of more than twenty years of knowing him, yet I consider him one of my best friends. My dear friend Karri Kokko is Finnish, and I've seen him in person only twice (though once for two weeks), yet I can count on him for kindness and a good run of English punning anytime I want. I like that the small time is filled with crazy people (even I am sometimes referred to with that adjective) and cranks (one of whom I actually identified as such yesterday on this blog and heard from, crankily, by this morning). I like that the small time allows for absolute freedom of expression and effort, because there is nothing to prove. Something might be proved, but it's not required, and we can decide what it will be.

Of the books I've had published (a strange collection of poetry, as viewed through various distorting lenses), I don't think any has been published in an edition over 100. And I'm fairly certain that at least a couple of the print-on-demand titles of mine that have been published have actually been made into printed copies under 50 times.

I have to conclude that this means our effect on the world is relatively small, but if I look at it from within the small time the term "relative" reverses its dimensions. We may be the small time, but my part of the small time reaches across the world. There are people in my part of the small time that I could fly to meet in dozens of countries, if only I had the money to pay for all that travel. The small time connects at the human level, the personal level.

The small time used to be relegated to the postal system and occasional personal encounters, but now we are tied together by the Internet, and we communicate with each other daily. I sent off an email yesterday to my friend Anne Gorrick with a poem of mine attached to it, and by today she had responded with this helpful message: "About yer poem: okay Font Boy, pick another font because this one is superhard to read!" Which really helped me understand how the poem was working and gave me the opportunity to tell her that her computer didn't have that typeface installed, so she wasn't actually looking at my font.

I laughed pretty well over that message of hers. Writing is a connection with an audience usually unseen, but writers of the same stripe find themselves connected and they form relationships across the boundaries of space. That's what I like about the small time. These are my friends.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 25, 2012 20:27

January 24, 2012

Bus Ride through a Drizzly Winter

Geof Huth, "tient" (23 January 2012)

Geof Huth, "tient" (23 January 2012)A few days ago, while talking to James Belflower, he asked me what I was reading at that particular point in time, and I said, Nothing. I was, at that point, between books, so I said I was waiting to see what I would be reading, that what I choose has to feel right as I prepare to read it, that I never know what it will be until I look at my bookshelves (and I have many of them) and choose something to read.

Last night, I found myself about to take a short bus ride in the dark. It is winter here, but it's been drizzling because the world is too caution to fall completely into the thrall of winter this year. While preparing for this trip, I ran to my bookshelves and scanned them quickly wondering what I would read and how I would know what it was. The answer ended up being a paperback copy of Bill Knott's Selected and Collected Poems. The first reason for this is this was a paperback book that I wouldn't worry about damaging during the bus ride. But other reasons are that an old friend of mine from college, David Daniel, knows Knott and has enjoyed his poetry; that I've always meant to read Knott more carefully, and I have enjoyed a few of his short poems; and that I've been talking, for the past week, about how frequently poets are cranks, and Knott certainly counts. And maybe the idea of a book of both selected and collected poems (in two separate sections) intrigued me.

So I headed out into the night. Once on the bus, I pulled out a pencil and a copy of Knott's selected and collected, and I began to read. There was a 1960sishness to the poems, a few echoes of Ginsberg, echoes of the New York School, but also something entirely different, something a bit wild, in love, destitute, despairing, and even life-affirming. Knott was a romantic, but with his crankiness starting to show. And the picture of him on the back cover (showing a man disheveled, slumped, and looking up at the camera with a bit of gentle despair) sits atop a biography that both indicates Knott is unemployed and looking for work and that mentions he has two manuscripts in his possession and "is seeking a publisher for either or both."

During the bus ride, I was able to read through only the selected poems, not the collected, so I'm responding only to that slender section of poems pulled out of his nearly collected poems up to 1977. In this group, I find a number of poems of only a few lines that are actually fairly effective lyrics, and among his most famous poems. I've run across references to them. He has a fascination with death and cemeteries, though I've no idea why. (Poets' biographies are not my interest, so I'm lucky even to know Robert Creeley walked around with one empty eye socket.) His poems are never sweet but sometimes plaintive. And they have variety. Some are written in a stripped-down lyric voice and others are written in a strangely formed dialect that resembles (neither visually nor aurally) one would be likely to hear. Some poems are filled with strange neologisms and latent words, like "cobblebubbled," "foreverth," and "visionvulsions." And he has some powerful, often powerfully sad but poetically so, lines. I underlined those lines and those strange words (with my pencil) as I read. When I was done, I concluded that the book could have been called Love and Death, if that were not already a comedic film by Woody Allen.

Today, I decided to write a poem using the lines from Knott that I liked the most. I had no idea what this poem would be, but I knew it wouldn't be like the poems I had been writing this year, spare and gentle, if sometimes guided by a stark view of life. I knew I had to write something different from what I was writing, because Nico Vassilakis had complimented my poems twice in the last week, on Sunday saying, "O, very nice. Good magnetics returning to the margin. Reads like a poem reviewing a poem which I always seem to like. And the sound is pleasure. Something is changing in your word poems that I've noticed. Enjoying." Whenever anyone tells you your poetry is good, it is time to change. That is why, as I've said in the past, we must kill Tony Trehy.

After choosing this poem, I decided to use the stolen lines (with changes, if necessary) in the order they had appeared in the selected. When I began to write the poem, I thought the poem would have long lines and be something of a ranting, a rending of clothing and wailing. But I wrote almost four lines that way, knew it wasn't working and created something else, the lines were shorter, but much longer than my lines have most recently been, and the voice of it has something of Knott in it, but not quite much, or not often much. If anything, this poem is most like Bill Knott's rant "To American Poets" (which I kept thinking was the poem Philip Booth recited to our poetry writing class once, but I really can't recall if that is so). This poem is a bit flip, which is something a little too easy for me (I have been accused of glibness more than once, possibly because I am glib), so I'm not sure I've abandoned my tendencies very much. I've simply chosen tendencies I usually exhibit outside the bloody arena of poetry.

So I'm posting this poem here because this makes my experience more one of writing than of publishing, and because this poem serves as the capstone to this my strange review of Bill Knott's poetry. (I don't go in for standard reviews.) To give you an idea which lines I've taken from Knott, I can tell you that most of the first line and the last line of the poem are from Knott, as are lines using these phrases: "your nakedness," "a petition for my death," "no shore to," "the world has no experience at being you," "filler for suicide notes," "both spectator and projector," "Therefore it must still be night," "if you are still alive when you read this," "the world is not divided into your schools of poetry," "the poems you broke away from," and "bread that weeps as you gently break it."

I hear a little echo of Knott in this poem, so it is a "Knotted Poem," but it is also otherwise knotted, as if into itself, into its twisted arguments, into my bones. And it may be the only poem where I have used the word "Geez."

Knotted Poem

I have never been in anyone'sdreams, or left anything behind there either, andI am breaking into morning using theshards left from smashing through the night andinto

your nakedness. Your white skin,paper, and upon it writtena petition for my death. Youcannot leave itbehind, you cannot remove it,and when you disrobe I can seeit. There is no shore

to your opening. Why have I never noticed before thismessage, which is a birthmark onyour inner thigh? How have I never seen youbefore? I remember the world hasno experience at being you, but I thought Ihad an idea what that being would be. How didI

never see that note on you? notfeel it whenever between your thighs? Truth is, Iam a poet. So whatI do is write filler for suicidenotes. Like"I love you." It is not aparticularly successful careerfor anyone who might want to beanything, somy goal has been to be nothing,which requires meto use every word up out of mybody. Poetry

is a great exhalation over anextended period of time. I mustremember not to take a breath inever. In this way, through thisact of poetry, I become both spectator and projector,both the movie andthe audience that believes itsits in the darkness,

yet it is covered with an oily yellowlight and peersintently, but slightly upward,into that movie sloshingover it. If you are stillalive when you read this,then I feel sorry for you, for Iwrote thisonly for your dreams. It seemsbest, to me

at least, that you perceivethese words as somethingonly half-real, and that you likelywill forget them, forget everything, forgetthe words between your thighs, the wordsof that plea for mercy. Oh, theworld is not divided into your schoolsof poetry. Each army clearly knowsits enemy,but they are fighting against everyone.Sure,

one side might say that thispoem isa lyric (I think I hear theplucking of a lyre as I type this), yet the otherwill say that I am exhibiting a distastefulmien

(well, if they know the word),that Iam, that my voice is, far tooironic to fita poem. As if this voice fitsanywhere! As if I am even here! What even makesthem think

I am here? Is it the fact thatthe word "I"keeps appearing? Geez, don'tthey knowthat is just my penis standingin for me? Synechdoche,they call it. I used to livethere until I movedto Metonymy. It's closer to workandreminds me of my hat. So don't

fret about the conflicts. Poetsdon'tknow what they're workingtowards. They are likebats swinging their pickaxesblindly in a goldmine while waiting for the canariesto expire. (We callthat metaphor, and it is particularto the province

of poetry. Reality, I believe, iscalled phor.) I am thinking about the poems youbroke away from, and howthey were too sharp for you,like shards of night, yet they were yourmost special

children, because they were theones youdidn't favor, the ones who hadonly themselvesto depend on. I know, I soundlike FrankO'Hara before the dune buggy,butright before. I am the gutturalscream, thehands held before the face as if

the flesh of palmscould hold off the metal and themotor. AndI know this poem is a piece ofcrap. They all are,but we can write only with our ownblood, and I

am coprosanguine. Everybody Icannot seeis sleeping around me, and Icannot heartheir breathing. Therefore itmust still be night. I chose this time to bestbe ableto worm my way into your dream,and I amsurprised by what I see here:Sunlight. Waterfilled with sunlight. Glasses ofwater filled

with sunlight. The bread that weepsas you gently break it into ears. Thesound of people hearing. (I cannotexplain it.) Notany smell, so no smell toopungent or

putrid. White linens, whitelinen pants, whitelinen tablecloth. Three stacksof white paper with a petition on each.Thenthe smell of pine, resinous, thescent of lemon,bright, and the mouth puckers,the tonguealmost speaks but can't. Singingthat I cannot

see. But nothing happens. Where,I wonder are the chases? thenearly failedescapes? the spurning ofadvances? thesuccession of failures? I find nothingmessy. So nothing poetic. Atleast

not in the manner of this poem.And everything beautiful. Again, notlikethese words. In your dream, youturn towardme and face me, and I see youseeing me,even though I am not dreaming. Iam

merely entering a dream. Somaybe youdon't see me and see rightthrough meto a red wall with some deepgreen mossgrowing between the bricks. I amlying

on the wall, so it is really apath toa doorway, and you are up highin the maples,maybe holding on with yourhands, yourright leg wrapped tight around abough, or you are floating in the barebranches

beginning to bud. I cannot seeyou well enough to tell. Still,I amastonished at you the way theworld is not.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 24, 2012 20:19

Since

Since there is evening.

Since there is morning too early to rise from.

Since there is language.

Since there is text.

Since text is physical, not ethereal like our tongued language.

Since text can be marred by physical acts and situations.

Since text can be environmental.

Since there is color.

Since text appears to us in the human landscape.

Since text carries meaning, even after we have forgotten how to find that meaning.

Since sleep is impossible.

Since text sometimes releases light during the night.

Since text may surprise us.

Since we assign to and find meaning in text based on its physical form.

Since text is not merely ink, or inked.

Since we experience text in a physical act of apprehension.

Since we accept text into our bodies.

Since we are people of text.

Since street signs and placards are text.

Since text is within us.

Since text is without us.

Since text persists without us but exists only with us.

Since we see the cracks in any textual meaning.

Since there is always a gap, however small at times, between meaning and meant.

Since a light rain in the winter can melt the snow.

Since the light that illuminates best may be the dimmest.

Since glowing is a powerful illumination, filled with warmth without being warmth.

Since the best discovery is the least expected one.

Since general statements cannot be true.

Since you didn't ask me.

Since you don't care.

Since it is the writer's job to make you see.

Since there are too many things waiting to be seen.

Since a text is a thing.

Since text can be of any size.

Since even tiny things can be meaningful.

Since words are a lungful but text is an eyeful.

Since my stomach is churning.

Since I fell asleep on the couch.

Since it is too early to wake but I am awake.

Since I can type in the dark because the text I make is aswim with light.

Since words in a row are the clearest way to make sense.

Since I sense a text in the darkness.

Since imagination is the search for the pre-forgotten.

Since I may not sleep.

Since you may not wake.

Since I am making loud burps that do not constitute a part of language but which are spoken by my voice.

Since all attempts are praiseworthy if made with real effort.

Since all failures are expected.

Since any language is too large to be expected.

Since error is everywhere.

Since a doryphore depends on a precisely defined set of expectations.

Since expectations are dashed.

Since text is fading when it is least ornate.

Since the light rises out of it.

Since the light seeps into it.

Since eyelids do not completely block the light.

Since every eyeblink is the disappearance of the world.

Since I merely walked away from this text afterwards.

Since you will walk away from this text, or already have.

Since text is patient, but history unkind.

Since everything is the unexpected.

Since when.

Since I said so.

Since we need it.

Since you must accept it.

Since you must accept it into your body.

Since always.

ecr. l'inf.

Since there is morning too early to rise from.

Since there is language.

Since there is text.

Since text is physical, not ethereal like our tongued language.

Since text can be marred by physical acts and situations.

Since text can be environmental.

Since there is color.

Since text appears to us in the human landscape.

Since text carries meaning, even after we have forgotten how to find that meaning.

Since sleep is impossible.

Since text sometimes releases light during the night.

Since text may surprise us.

Since we assign to and find meaning in text based on its physical form.

Since text is not merely ink, or inked.

Since we experience text in a physical act of apprehension.

Since we accept text into our bodies.

Since we are people of text.

Since street signs and placards are text.

Since text is within us.

Since text is without us.

Since text persists without us but exists only with us.

Since we see the cracks in any textual meaning.

Since there is always a gap, however small at times, between meaning and meant.

Since a light rain in the winter can melt the snow.

Since the light that illuminates best may be the dimmest.

Since glowing is a powerful illumination, filled with warmth without being warmth.

Since the best discovery is the least expected one.

Since general statements cannot be true.

Since you didn't ask me.

Since you don't care.

Since it is the writer's job to make you see.

Since there are too many things waiting to be seen.

Since a text is a thing.

Since text can be of any size.

Since even tiny things can be meaningful.

Since words are a lungful but text is an eyeful.

Since my stomach is churning.

Since I fell asleep on the couch.

Since it is too early to wake but I am awake.

Since I can type in the dark because the text I make is aswim with light.

Since words in a row are the clearest way to make sense.

Since I sense a text in the darkness.

Since imagination is the search for the pre-forgotten.

Since I may not sleep.

Since you may not wake.

Since I am making loud burps that do not constitute a part of language but which are spoken by my voice.

Since all attempts are praiseworthy if made with real effort.

Since all failures are expected.

Since any language is too large to be expected.

Since error is everywhere.

Since a doryphore depends on a precisely defined set of expectations.

Since expectations are dashed.

Since text is fading when it is least ornate.

Since the light rises out of it.

Since the light seeps into it.

Since eyelids do not completely block the light.

Since every eyeblink is the disappearance of the world.

Since I merely walked away from this text afterwards.

Since you will walk away from this text, or already have.

Since text is patient, but history unkind.

Since everything is the unexpected.

Since when.

Since I said so.

Since we need it.

Since you must accept it.

Since you must accept it into your body.

Since always.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 24, 2012 00:19

January 22, 2012

A Certain Friday Night in Albany, New York

Coming into the middle of the first third of the reading, I am hit with a story, one slowly told and with no perceptible point. Things happen. The end. But things don't even happen. We are told they are. The narrator tells us people believe he is dangerous without demonstrating his danger.

I shift in my seat. I've been here only a few minutes.

The second reader was a musician for many years. Now, a poet, teacher, student. He says he will "read from a number of my favorite poets." He says, "I only brought lady poets." I cringe. Then he says "lady poet" again, in case I missed it the first time. He reads the first poem to us. Declaims it. He stops to tell us: "Poetry works on a spiritual level other writing can't." I don't believe it. I want evidence. He reads the poem he says is his mission statement for the night. It is a dead poem. It arrives dead. He buries it. He reads another poem, the title of which may be a reference to Aldous Huxley or to the Doors, or he doesn't know the reference. The poem includes the line "feeling safe in the rapist's embrace." He reads the poem jauntily. I bow my head slightly and rest it on the tips of my forehead, preparing myself to continue, quietly, in my chair against a wall. He reads Sylvia Plaths' "Tale of a Tub." Also jauntily. He reads everything the same way. Maybe we all do, and I simply haven't noticed.

His reading continues. He says, "I told myself I'd never write a hangover poem," just before reading us his hangover poem. This poem, all of them, are filled with adjectives. I have no aversion to adjectives, but there are so many that there is no poem; adjective-noun, adjective-noun, adjective-adjective-noun, goes the poem. The pattern seems like prosody, but the poem is empty of poetry. He tells us that the next poem needs some explanation, and gives an explanation that the poem also gives, but the one he gives us first is much longer than the poem itself. We need a library's worth of explanation for a line's worth of poem. His next poem with a one-word abstract noun as a title, and says, "I learned today that it will be in the Something Review, a pretty good little magazine, am I right?" I hold myself in place. There is another poem after this, then he ends with "Thanks for listening, guys." I am empty, like one of his poems.

Between the first and the second and the second and the third reader, I hear the intros. These are beautiful, read by James Belflower. Short bios followed by a beautiful reading of a poem that the two organizers have fashioned out of the individual poet's work. And his voice is beautiful, deep but rich, and always in motion, always changing its stance. At this point, his is the best reading by far.

Then Anna Elena Ayre appears. She is tall, with a strong nose, more striking a presence than the men who preceded her. She begins with poems from a pronoun series: "He," "She," and "I." Each line of each poem ends with the pronoun that is its title. This causes as strange sonic discomfort, but good discomfort. We are thrown off. Almost every end of a line has to move to a verb, but instead we are stopped. And every poem has an AAAAAAAAAAA rhyme scheme. I begin to write down lines to remember: "is is is was was," which is fully "says is is is was was were you he." Her language is inventive, disjunctive, urgent. She reads with a voice that trips and rolls over itself as the words do the same: "word a word collapsible i," "press body against body to feel strain i," and "i / can't think to think what that thought is." By the end of this poem, her i's are gasps, orgasmic, coming, done.

I am awake again. Those, I later discover, were from her chapbook "are me."

Next, she reads from her "first book with a spine." She begins with letters written to William Carlos Williams about his "Kora in Hell." The poems are numbered. She reads "six." "bloodoranges interbreedable citrus" and "snowless mouth." (With the book in hand, Faceless Names: Two Books of Letters, I discover she has misspelled this word: "pairingknife.") She reads "nine": "the scare is invisible," "best words are written beasts," "thumbs in your anus," "your third eye is color-blind."

She reads from the second section of the book, "Nameless Mail." They are letters written to a grandmother she never knew: "one can live off air and light on mesa land." At this point the older woman two seats to the left of me starts snoring loudly. After a while, Anna realizes it and looks around. The man just to my right says something like "It is what you think." We all laugh loudly. When the laughter dies down, we hear the snoring again. Anna looks at the woman and says, "It's kinda sweet." And she finishes reading her poems to Evie—"lost in rhetorical abandonment.

It was a good night.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 22, 2012 20:27

January 21, 2012

The Regeneration of Rae Armantrout out of What Rae Armantrout Would Eventually Become

Rae Armantrout, "Generation," from Extremities (1978)

Rae Armantrout, "Generation," from Extremities (1978)Gretel is not among us, never having made it out of the woods.

I am entranced by the words of women. Their voices may be so much different from each other, as is their eyesight (vision), yet those are the voices I yearn for, lean into, require. Women seem to have an advantage over men with language, for which reason I (so pathologically verbal that I function well only within the realm of language) spent much of last night talking to James Belflower about the fact that all my favorite living poets are women, that I don't even know which male poets to read. Even though I do read them.

Rae Armantrout has been putting out books of poetry since the year I graduated from high school, and I read that first book of hers ( Extremities ) a couple of days ago, hearing in it the voice she has today, and finding within its too few pages all these recollections of poems I'd never read. As if her voice 34 years ago was an echo of her voice today.

One small poem, her forte, that stopped me was "Generation," a brief retelling of "Hansel and Gretel," by my reading, and focused on Gretel. The brevity of this is stunning to me. Its power in so few words. And how those words are used: the first line presented as a whole sentence; the severe enjambment after "turns" and "the"; ending with the unexpected but revelatory "undergrowth."

Only a day before this, I had created my own allusion to the same fairytale in a strange long entry in my poetics and written as a response to Anne Gorrick's review of her life with Sylvia Plath:

Everyone is lost in the woods. We ate all the breadbecause we were lost in the woods. No crumbs dropped for the return. We don'twant to go home anyway. We want to make a new home, to find a new place to be,a new way to be. So we are searching.

In comparison, I am verbose and maybe even lacking in imagination. Still, I like these words well enough.

What amazes me most about Armantrout, though, is how little her style has changed. It is as if she were born a fully formed poet and merely continued in the direction required of her. The words are short, careful, arranged like china and silverware at a banquet, and somewhat elusive (when not allusive). She doesn't say as much as she means, and she does this quietly, efficiently, as the craftsperson and the artist that she is.

Originally, this book cost US$2.50, but I paid many times that much for the book, a dear price for a small book, yet a reasonable price for us. Her words make demands of me and they nourish me.

As a woman making demands of those in her care, yet always focused on that care.

_____

Armantrout, Rae. Extremities. The Figures: Kensington, Calif., 1978.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 21, 2012 13:50