Geof Huth's Blog, page 21

November 8, 2011

W

Geof Huth, "W" (8 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "W" (8 November 2011)Maybe sometime I will complete my search and find every letter of the alphabet in its native non-paper environment, and this means letters meant as letters, not shapes resembling letters. This W rests in a little world of vinca (cf. PERIWINKLE).

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 08, 2011 20:40

WGeof

Geof Huth, "W" (8 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "W" (8 November 2011)Maybe sometime I will complete my search and find every letter of the alphabet in its native non-paper environment, and this means letters meant as letters, not shapes resembling letters. This W rests in a little world of vinca (cf. PERIWINKLE).

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 08, 2011 20:40

November 7, 2011

From Sea to Dark and Unseen Sea

View from the Poet Hut to the Real House, Portland, Oregon (5 November 2011)

View from the Poet Hut to the Real House, Portland, Oregon (5 November 2011)My original plan for the night was to write a modestly detailed review of the Object Poems exhibition that opened in Portland, Oregon, last Friday, but I do not have the energy for that at the moment, so I'll write about one of the ways in which poets succeed at what they do: support from others.

The reason I finally decided to visit Portland for the weekend wasn't because I really wanted to attend the opening of this exhibition (though I did) or because I really wanted to take part in the reading the next day (though I did), but because Maryrose Larkin offered me lodging in her and her husband Eric Matchett's house for the weekend. That significantly reduced my costs, and gave me an experience I would not want to have missed. For that reason, I flew from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific on a quest for poetry.

Maryrose is the one who picked me up at the airport at about 4:15 in the afternoon, just after my plan arrived, and then drove me to the opening, getting me there before it started at 5:00 pm. Even though she was taking a three-day workshop while I was in Portland. She returned to find me after the exhibition opening, and she joined a group of us at Spints (no-one knew how to pronounce it) for dinner and drinks. Then she drove me home. She missed much of the reading, but still made it to the venue in time to see one set, including my piece.

My friend and fellow archivist Terry Baxter also attended the opening, bringing with him his belle, Debbie Jewell. I had a great time with the much-tattooed Terry, and even decided that he himself, his body itself, was an object poem, since all of his tattoos were primarily textual. He intends to donate his body to poetry some day, or so I hear. It was great to have a good friend in attendance, and to spend time with him where we'd never been before.

A number of poets came to the show and reading from out of town, even Joe Keppler, coming from Seattle. I haven't seen Joe in a few years, but Joe was an important person in my poetic life. His magazine Poets. Painters. Composers. was one of the mainstays of my life during the late 1980s. In those years and the early 1990s, Seattle was really my literary home; I was more connected to what was happening in Seattle than anything going on anywhere else. And seeing and talking to Joe reminded me of the strength of those bonds that those of us Seattle poets had, no matter where we lived.

I was carless (not careless) in Seattle (neither was I sleepless), so I needed help getting around. When the always attentive Maryrose wasn't available, Eric drove me to Powell's, where I bought many books. And after that, David Abel picked me up at Powell's and we had a great lunch at Pho Jasmine and then visited his studio, where I bought more books, including a few great items of visual poetry. After the poetry reading, many people offered me a ride to dinner, but I stayed with David, since he had my bags. After the après-poésie dinner and postprandial bar visit, Nico Vassilakis took over and drove me back to the Poet Hut.

And so we return to the end, for the Poet Hut (AKA the Poet Huth, for last weekend) is that outbuilding behind Maryrose's house, and I enjoyed a last night there. I was quite tired, but I packed all my bags quite carefully, being especially careful to protect my books, and then I slept the night away in a comfortable bed piled high with blankets and pillows. I didn't pay Maryrose back well for her generosity. I did get to pay for parking at the airport (three dollars? is it even worth charging for so little?) and for her dinner on the first night. And I did give her a book of mine and mIEKAL aND's, but they were just pwoermds, and do one-word poems really county?

But there's no paying people back for this generosity of spirit. The world of poetry, as my friend Anne Gorrick likes to say, is a gift economy. I'll have to give another poet a gift of great but inaccessible value sometime to pay Maryrose, and all these other folks, back.

Huth ffrey (AKA I) Pay My Dinner Billecr. l'inf.

Huth ffrey (AKA I) Pay My Dinner Billecr. l'inf.

Published on November 07, 2011 20:46

November 6, 2011

I Wrote a Book Today

Anna and Leo Daedalus, Ten Rocks with Their English Translations (copy f of h) (2011)

Anna and Leo Daedalus, Ten Rocks with Their English Translations (copy f of h) (2011)(Note that this book is a translation of rocks into English)

I thought I would be writing about one of the events in Portland today, but instead I read a book today, and that caused me to write a book, not a large book, but a book of hundreds of small poems, each written into the 400-page book I read today. I read and wrote for five hours as I moved through the skies (in a window seat with a wall instead of a window) from Portland, Oregon, to New York, New York. But I failed to write the introduction to the book on that flight, so I wrote it tonight on my train ride from New York to Albany. It is but a first draft, but this is all of this little book (one poem to a page it'll be about 200 pages long) for now.

* * *

(in parenthesis

frgmnts from the Greek

movements out of the English made of Sappho

INTRODUCTION

OF SAPPHO

Sappho (or, more properly and rarely transliterated,Psapfo) is the most famous Greek lyric poet, if not the most famous in theentire ancient world. For millennia she has been known as the tenth musebecause of her lyric skills: the power of her words, the subtlety andoriginality of her meter, and even the music she wrote (none of the last havingsurvived). A native of the Greek island of Lesbos from the sixth century BCE,she is the ultimate cause for the more general term "lesbian," which is aconcept born from her poems, where she often expresses some physical tendernesstowards women.

The power of Sappho's verse derives not entirely from theextant store of her poetry, which is quite paltry: a couple complete poems andalmost a couple hundred fragments, many of only a few words, or less. Thevividness of her verse comes from what is no longer there. It extends out ofthe lacunae in her verses, the blanks that we fill in with our minds or whichwe hear as gentle pauses within fragmented speech. We also believe in thebeauty of her verse because the ancients did; they extolled her verses, seeingin her a master poet. To some degree, the abated but still real controversyconcerning her supposed homosexuality, both draws the salaciously curious andthose who feel a need to honor the fact that homosexuality is a permanent humancondition. Although it is not a condition of most humans, it is one thatextends back in time before the ages when history was recorded.

None of this is meant to question whether Sappho is agreat poet. Even given the phrases she often repeats, the aching beauty and thetrue and various emotion of her poems comes through, here and there, in thefragments, and we are left to mourn what we have lost.

OF TEXT

Sappho is said to have written eight, sometimes nine,volumes of verse, so very little of her oeuvre survives, and what does is oftenof questionable authorship. Scholars disagree about what are true Sapphic poemsand what are the apocrypha. Many of the surviving fragments of her poems do nothave her name associated with them on the papyrus versions, and the questionremains how these poems may have changed through the repeated process ofscribal transcription over the centuries. The truth is that much of Sappho'spoetry is missing because of a concerted effort to destroy it—her apparentcelebration of lesbian love being more than many, especially the Christianchurch, could abide. Willful destruction probably has done more than centuriesof neglect to erase Sappho's verses, but never her, from our culturalconsciousness.

Her fragments (and those two complete poems) come to usin two separate ways: Most come to us in the moth-eaten form of fragments wherebits of the text have fallen away, leaving occasional gaps in the lines, theeliminations of the left-hand side of the poem, the loss of the end of thepoem, etc. Most of these fragments are quite short: under ten lines in length.These are the romantic remainders of Sappho, those that most people who know ofher imagine her poems to be. When Ezra Pound wrote his three-line andthree-word poem about the absence of Gongyla, he was hearkening back to thesefragmented pieces of Sappho. He ended each of his lines with ellipses totelegraph to us the voids in the poem, and it is precisely those voids thatmake the poems romantic and reverberating to us. The second way that Sappho'spoems come to us is much less romantic, and much more whole. Since Sappho was agreat poet of her age (and all the ages that followed), writers on rhetoric,poetry, and grammar often quoted lines from her verses to give examples ofwriting in action and to support their own points. Often these quotations camewithout any important focus on Sappho while inadvertently rescuing whole linesor two from Sappho. All of these are complete from beginning to end, so thereare no voids with these quotations, but each remains a fragment of a poem.

Most speakers of English have no ability to read ancientGreek, so they depend on translations to form any opinion on Sappho. I am thesame, so this book before you (mine, not Sappho's) is inspired by translationsby Anne Carson of Sappho into English. Carson is herself a great andmarvelously unique poet as well as a great scholar of the ancient world, so sheis probably the most likely person to translate Sappho well for us. For thatreason, I searched yesterday for her book, If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho,in Powell's flagship bookstore in Portland, Oregon, and I found a fine copy ofthe book itself with a fair dust jacket (a little soiled from wear and withsomething spilled on part of the top front edge). Today, I read the entire bookas I flew across the country, writing in it as I did.

Carson herself had to base her own translation on a text,and she chose Eva-Maria Voigt's Sappho et Alcaeus: Fragmenta, published inAmsterdam in 1971. Carson opted to translate only those fragments where atleast an entire single word was present. Every act of translation is a sequenceof choices, an attempt to make a different but similar whole out of anotherwhole. Some of these wholes are merely series of fragments.

When I opened Carson's book today, I did not expect towrite a book of poems from it, but I did expect it to engender a few smallpoems of mine, since I often write minimalist poems inspired by a word or aphrase I read in other poems. As I continued reading in this book, however, Inoticed that there was something about Carson's translation (unlike others Ihave read), something about her word choices and phrasings that encouraged meto respond to each poem, so I did. Using a mechanical pencil, I wrote a poem,almost always one line in length, somehow inspired by the poem on the page. Iloved the process, and I write only for the love of writing, not even foranyone to read what I make. Carson's translations were more understandable andmore literally inspiring than others I've read, so I have her to thank, but Ihave much else to thank her for. As I always say, all of our great poets now(poets writing in English) are women. In general, they seem more oral than men,and that deeper connection to the language, and the bravery they often show intheir writing, makes them better than us poor lesser sex of poetry. (I basethis only on the fact that all of the living poets I most love are women. Allof them.)

My little poems have the aura and style of othersequences of short poems I've written, especially those directly inspired byother poetry. This inspiration, however, may seem indirect, because I mightsometimes take a single word and make something almost entirely different ofit. The two poems might have no more than a single word in common. Often, inthis sequence, I do create poems out of words I find wandering in the text, orI riff off the words in the original text. This process of riffing extends intothe academic appenda in the back of the book, so my poems continue in the notesto the poems, and even to the glossary, that appear in Anne Carson's book.

This book does cohere, though; at least it seems so tome. It is a book governed by the interests of Sappho herself, so it is a bookabout love and desire. It reads as a book about relationships, and it iswritten to be such. Inspiration is one thing, but creation is another. Sapphoand Carson are my muses here; I am still the poet. All blame and disdain aremine to keep.

ON MARKINGS

The omnipresent markings in the book are the numbers thatidentify each poem. These numbers are not from me; these are the common numbersused to identify fragments of Sappho, and I must assume that the numberingsystem follows assiduously that of Eva-Maria Voigt's Sappho et Alcaeus. Withthese numbers, any reader can relatively easily return from my poems toSappho's originals to puzzle over how mine were created out of hers.

I do not follow Anne Carson's marking protocols at all.My marks do not designate, for example, lacunae in the Sapphic text. Instead, Iuse all markings simply as punctuation. I believe that punctuation is apowerful tool of meaning, one that creates more sense than we usually realize,and always silently, always by defining the type of pause we must take tounderstand something. So two square brackets facing each other, two of thesebetween a void, show that something is missing. If words are inserted betweenthose brackets, then those words are intruders inserted into the text from anomniscient source. Ellipses might show elision of words already in place ormight show the trailing off of a thought. Words between parentheses are asides,or extra thoughts whispered at the reader. Commas show brief pauses. Dashesdemonstrate a wrenching extension of a thought; colons show that what followsthe colon explains or deepens the meaning of what precedes it. Semi-colons showthat two separately expressed ideas are equal in value and meaning, thoughdifferent enough to require a semi-colon between them. Words between quotationmarks are supposedly quoted material; here they represent that someone isspeaking, probably someone other than the poet. Apostrophes show elisions intwo words brought together or mark, with the s, the possessive case in nouns.Hyphens hold the two unnatural parts of a compound word together. Virgulesrepresent slashes, which represent the line from John Berryman: "O and aslash." Question marks mark a sentence as a question.

There are no periods in the poems in the body of the book(except to mark abbreviations), just as there are no capitals starting eachpoem. Initial capitals and periods are relegated to the notes, which are alsopoems, but poems of reference back to other poems. They are poems constructedof the mechanics of scholarship, even though they are not scholarly.

Punctuation controls the making of sense. I usepunctuation to poetic effect, just as I use the pun. It is possible that all apoem needs to survive is punctuation and a pun.

6 November 2011

on a train heading north

from New York's Penn Station

to the Albany-Rensselaer Station

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 06, 2011 20:59

November 5, 2011

A Note on a Night

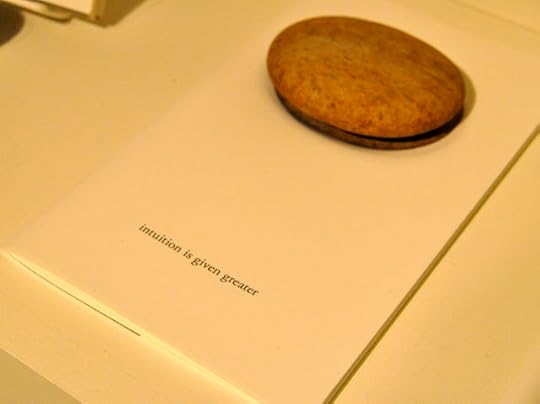

Anna and Leo Daedalus, Ten Rocks with Their English Translations (copy b of h)" (2011)Portland, Oregon, Northeast

Anna and Leo Daedalus, Ten Rocks with Their English Translations (copy b of h)" (2011)Portland, Oregon, NortheastThis is my second and last night in Portland, and it's been a good time too filled with activities to recount now, just about five hours before I arise to leave for the airport.

Let's just say that there was a great crowd at the exhibition last night, and that was a great success, and tonight we had a great set of readings. Much to think about further, but all I'm going to think about tonight is sleep.

The book above (complete with rock) is a book I purchased from the show. Don't think I've ever purchased an item on exhibit before, but this one is translations of rocks. For instance, the rock above translates into "intuition is given greater."

Goodnight, Portland.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 05, 2011 20:48

November 4, 2011

Theogony Recapitulates Cosmogony

Geof Huth, "where are we? (version 2)" (4 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "where are we? (version 2)" (4 November 2011)Written on Two Delta Flights: JFK to SLC and SLC to PDX

The title of this attempt at a review of Douglas Rothschild's book of poetry, Theogony, a text that seems to avoid criticism by being both all things as well as often being flagrantly apoetic, is an old saying of mine, and an important one. If you want to define the settledness of existence (are we not all solipsists at heart?) by defining first things, you'll always find that you cannot define a believable inception, only a continuance.

Douglas' book is not so much a book as seven books. Thematically, they cohere in interesting ways, even if sometimes provincial ones, but stylistically there is a wide range. Douglas has inscribed my book thusly:

October 28/11And I did enjoy all seven of these books, for various reasons, in various ways, which I might be able to explain through a process of emulation:

Dear Geof,

Two EBay or not

Two Ebay that is the

Question. Weather or

Not weather is it more

important to shovel or

Leave town.

Hope you enjoy this book

[signature replicating a desultory paraph]

Textual Queries

Moored not mired

in smallness that

"if long beetled up"

might foment but

the question lofts

without lifting the

words come with

faces of gulls and

dirty water thinking

and quoting forth

not froth

Christmas Book

Well like my eXmaSscards that mark not Christmas

(X'd or not) or winter solstice (given me not another

religion to replace the one I've already dispensed with,

and don't think my gods'd be sylvan over oppidan)

or even year's end since any ending made per annum

(though not the processeses therein) is based on centuries

of arbitrary actions of thinking—

these poems move against articles of faith by

ignoring them, and toward

a sense of self in place, not stable, nor stasis, tho

movement is mostly of mind and eye, resulting in

actions of thinking somewhat sad, of, say, the poet's

own personhood, but more broadly of society

and infrastructure (is Douglas the great poet of

infrastructure?), and all the sadder for the fact that

when it rains near Christmastime, it always rains

cold

Last Day at Work: Trip to X-Towers

i tell a story only of

a set of poems I've read

so not telling those of

how I saw 9/11 through

a blurry TV screen

then a week or so later

as craters. Douglas tho

sees it as a place of his

often going. He returns,

there is a badpennyness

to him, to that place and

thoughts engendered with

strange linebreaks strong

for there wrenchtness,

but why these misspellings?

do they have meaning?

are they intentional?

"momento"

"911" for "9/11"

(a minimalist i, so i see

significance in the slightest

change of sign or signification)

see how what we make

makes us

& with Douglas we see

the provincialness of New

York (cf. Saul Steinberg's

view of New Yorkers' view

from 9th Avenue). Everything

so small and given over to

rubbish.

FEBRUARY 28, 2001

Lines lengthen for some sections as they shrink for others. The guy

in the seat ahead of me has just reclined his seat into my laptop

screen, making it a little more difficult to type into the V of my

computer. Everything valley and valiant.) Douglas plays more,

in this middlest book with language. So we have his discovery of

"Pierage" as New York's piers are gentrified, and the echo out

from "Peerage." He is the poet of the 99% (or the 75%), frowning

at both the overcaring given the rich in this country and

all the irrational thinking that makes it work. All of which thoughts

come out of the small things of the world: handwritten signs,

for instance.

And in this section is the greater book's third reference to "the

figure 5," reminding me not of Williams (WC), but of Ted

Berrigan's recurrent 5:15 am—maybe because an occasional

character is Ted's son Anselm, who might walk some nights

with Douglas, even if never speaking Finnish once.

Poems from a Green Notebook

Water there is in many of these poems

taken along a river and night in the sense

of darkness if not sleep. His is the urban

nightscape and riparian, the city slowing

giving way to the water always moving,

a permanence to it, and a lonelinesss, for

except when Douglas is funny or angry

(always coterminous) there is a melan-

choly sense to his adumbrations (sad

but a calming sadness, "not complete but

continual forgetfulness"). Douglas is

not a language poet, not a lyric poet,

and neither is he neither of those things.

He doesn't postcede any before who came

after those who had come before and he

doesn't pass anyone who has passed him

or out and he doesn't be except himself.

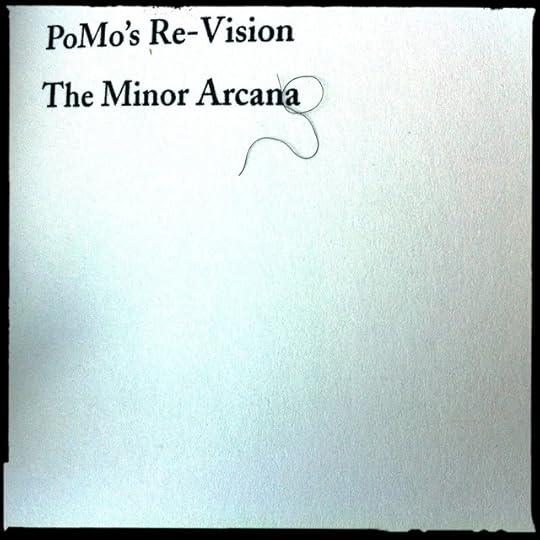

Pomo's Re-Vision

The process of extending a process also in place

is the fact of remaking the made

In this book the poems function in blocks and breakup into scattered sections of words, language brokeninto incohereable pieces that do not create continuances of language

in thewith aby thefor a

to aa toto a

for thethe forfor the

night

It is the play of languagethe play of the tongue

Here he starts in with humorhis righteous voice rising in a couple of poemswith "9/11" in their titles

Here are references out to poemswe'll never know the straw man of(but certainly not Eliot)

everything fragmentsand fractures

Poems as titleswith epigraphs withsingle lines referringto something thena footnote to send usfurther astray

At play in the field of the Word

HereDouglas uses "then"for "than"

A g I Found in My Copy of Theogony (Yes, I Know What the g is Made Of)

A g I Found in My Copy of Theogony (Yes, I Know What the g is Made Of)The Minor Arcana

Douglas presents himself as Jack Spicerwith Lorca: a woman named Mara Gilbert(who may be this actress who is a friendof Tony Dohr, AKA Douglas Rothschild)opens the book with an explanatory essayabout this set of 56 numbered poems, which could be an essay by himself.

1

Hey, each one of these is numberedin the book, so each one of my micro-reviewsis numbered here. Can you not understandhow this works? It is a process of convergencebetween the writing and the reading. Eachact of reading being a subsequent actof writing the reading out of oneself.

2

This book sounds like Douglas, he talks as

he speaks, he yells as he shouts:

"i was like, NO! NO! It's Steinbrenner.

Doesn't anyone remember?" which is pure

Douglas. I've heard him speak in this way

many a time. He is a political ranter, and

the politics is politics or capitalism (the

difference is?) or poetry or the media.

3

He rants against the media. Against us,

against Americans so afraid that they'll

give up any right to pretend they are safe.

Against the calculus of fear that keeps

people docile, even when they seem

angry. This is all pre-Tea-Party, pre-

Occupy-Wall-Street, pre-Occupy-

Oakland-and-Shut-Down-Its-Port,

but it presages it. Douglas was angry

before most of us were, and his is

a kind of political poetry so specific,

so specific in the details of its rancor

that we might not be able to under-

stand it

fifty years from now, but it has thesound of something real. (For 1980szinesters, there's something in the cadence and language of these poemsthat reminds me of the White Boy poems of Paul Weinman.)

4

I worry about poets who are, as I say,"trapped by their tropes," who do overagain what they've done so often before.Douglas' poems cohere somewhat inlanguage, yet this rambling (becausemultiply-focused) rant of his is something different than what's come before.

The bile has risen higher, the languagehas been stripped of its poetry so thatthe poetry is the outrage itself, he speaksnow in the cadence of a preacher againstevil in Washington Square Park, he isall colloquialism and slang, the languagethwacks against the side of the head,then thwacks again, it's a poetry writtenas if poetry actually matters, and

we have to thank Douglas for that.

5

The most I ever do in this regard is to mock

the language of politics, which is shrewd

without being careful or meaningful to us:

thus this tweet of mine from today:

This tweet from NYGovCuomo is the problem with government today: "Governor Cuomo Reports 98 Percent of Power Outages Restored." Why put forth so much effort to restore something no-one wants. Who's ever said, "Give us back our power outages"?

Douglas could do better.

***

Douglas ends the book with a prose coda, in two columns per page (and we have to assume the columns are meaningful). In this, he discusses how people tried to make sense of the attacks on the World Trade Center, and he demonstrates how any deeper meaning is immediately undermined, that it carries no meaning, only carnage from external sources followed by carnage from within. (I'm paraphrasing, extending, reading what I see within his words.) It's a totally serious piece of writing, devoid of humor or arch statements. And it ends with one rabbi's statement that he would read the messages of those people in the World Trade Center on September 11th who knew they wouldn't escape, those messages out to their family, and how the rabbi believed that reading those statements taught him the meaning of this event. And then Douglas quotes two of those messages, voicemails, I assume: one that sounds like a man's message to his wife, another that sounds like a young woman's message to her mother. They are both messages of love, they both indicate that the speakers expected to die, they were both messages of goodbye, and they are short and simple. But they give no meaning to the event. People were murdered en masse, followed by the problems of a country dealing with these murders in ways that often made things worse.

A powerful ending to a book that is really just a human book about living. Maybe Douglas is simply a lyric poet (the "i" [never "I"] is always him). Or maybe he is the crazy man talking in the subway train, which moves through veins of darkness carrying all the light within its body.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 04, 2011 15:19

November 3, 2011

Textual Fashions

Somewhere in Astoria, New York

Tonight, as a prelude to my trip to Portland, I attended the opening of an exhibition at the Fashion Institute of Technology. (I'm not much of a fashion maven, so I think I was the only person in a conservative suit, and people kept telling me certain expressions of fashion around me were good, even though I remained unconvinced. Still, I have to admit that a Swarovski crystal brooch in the shape of a spider the size of a hand was an impressive piece of jewelry for a man to wear.) The exhibition, put on by the Department of Special Collections and FIT Archives was entitled "Incomparable Women of Style: Selections from the Rose Hartman Photography Archives, 1977-2011."

My interest in the exhibition is, in part, professional, since this was an exhibition from holdings of an archives, and since this archives is part of what is actually a local government in New York State, and thus must follows certain regulations that I have helped to write governing the management of records. And the department is run by my friend Karen.

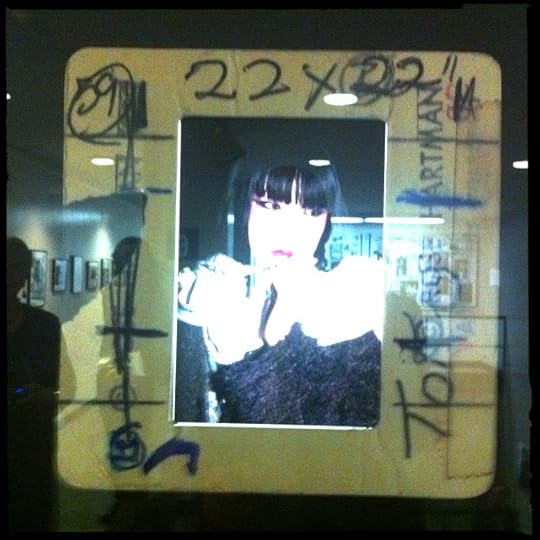

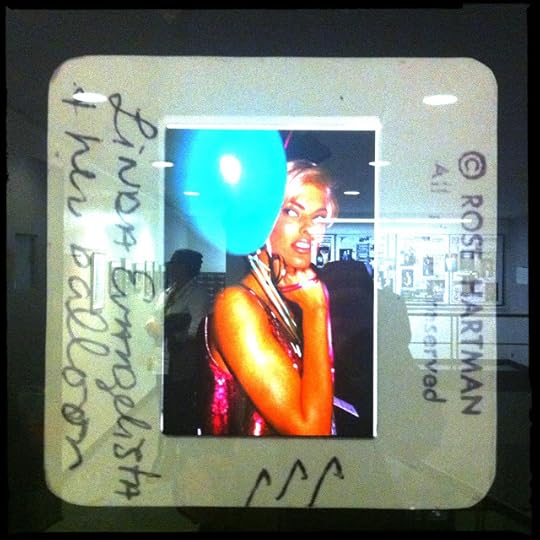

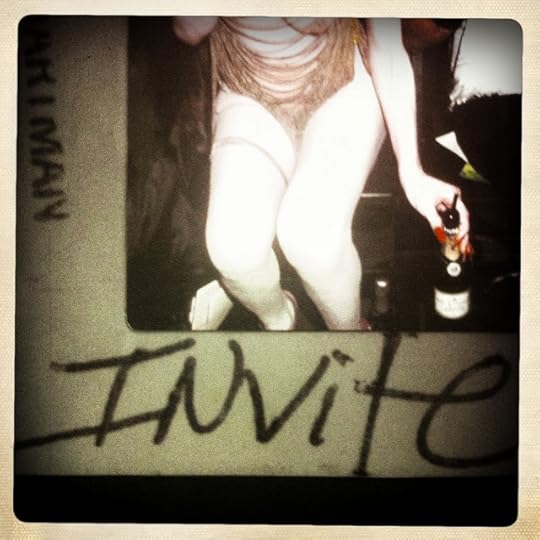

I could explain the way parts of Rose Hartman's career were segregated on different floors of the library, and I could note that the entire exhibition is installed in a stairwell, yet the stairwell is so huge and bright that this ended up being a benefit instead of a detriment to the show. But my focus here is in the visual presentation of language, in text alone or married to image, so I'll focus on what I think was the most innovative part of the show.

Hartman now shoots digitally, but she used to shoot in film (none of which is surprising), and since most of her work was in color for glossy magazines she produced thousands of slides, all of which are marked with text in some way. As a matter of fact, for most of the images in the archives, there are no paper copies. Instead, the slide, which is the original image and also one of positive, not negative, polarity is retained as the only copy. Which seems sensible to me.

But it is difficult to display 35mm slides since they are such small things, and since no-one wants to bend down over a lightboard with a loupe jammed into one of their eye sockets. So the organizers of the show reproduced the slides at about 20 times their original size. They did this by turning standing vitrines into lightboards, by blackening most of the "windows" of the vitrines, and directing focused light to shine through only those enlarged diapositives. They reproduced the slide images, in vibrant color, on large sheets of plastic. That is amazing enough, but then they added the text: they printed reproductions of the slide borders (I'm forgetting the real term right now) on thick card that really resembles the borders around slides, and upon these margins of the slides we find all of Rose Hartman's marginalia (generally, rushed metadata about the image).

The clarity of these images and their surrounding texts do not come out in these images here, because I shot them with a Hipstamatic app on my camera (and I did that because that app produces a square picture, just as the original slides were square. These images do give some indication of the interesting interplay between sometimes rushed and candid but also artful photographs and the definitely hurried texts, which consist of stamped identification of the photographer, handwritten notes about the image or how to print it, and and amazing amount of scribbling out of information.

I do enjoy my metaphotographs of the original copies of these slides, because they add another element. The reflections off the glass invade these images, putting them in a particular place and time, just as the original photographs were in such specific places and times. And my app distorts the images into new things, new ways of seeing. But the main difference is that the frames around the slides were originally meant to be seen as separate from the text, but my images of these slides integrates the text and the image.

The first two of these images here are meant only to be documentary, but I did take other pictures, pictures where I focused on text or the eradication of text. Those experiments in creating visual poetry from these reproduced slides were not hugely successful, but now I want to look through the thousands of slides and make a huge number of poems from the ignored parts of these images.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 03, 2011 22:28

November 2, 2011

The Object of Poetry

Joseph Keppler, "Five Poets and No Poem" (2007)

Joseph Keppler, "Five Poets and No Poem" (2007)Every trip begins with the imagination of the trip, so tomorrow I head out to New York City for the opening of a photographic exhibition, and from there I will fly the next day to Portland (not the one in New York or Connecticut or Tennessee or even Maine, but the one on the other side of the country, in the state of my great-grandmother's birth) for an exhibition of object poems.

Almost every one of the object poems, sculptural presences of language, are already available for viewing in the exhibition's online gallery. Curated by David Abel, this exhibition pushes the definition of poem quite a bit more forcefully than even the idea of sculptural poetry does. Joseph Keppler's remarkable piece above is just one of these. At first glance it might seem wordless, and thus not able to be poetic, but each piece of the poem is cut out of an I-beam, every one of them is an I, a person focused on him- or herself and thus not capable of focusing outward at the world, or even at the creation of a poem. Each I (the title tells us this) is focused on self-definition rather than on generative actions leading to poetry.

But Joe's is an easy piece to dis- and reassemble in poetic terms. Others are totally wordless, or consist only of marks that do not even resemble text, or they suggest that the viewer/interactor considers poetic processes while considering or handling the works. None of which bothers me. A hard definition of "poem" allows for some clarity, but when was poetry concerned primarily with clarity. The poets assembled in this exhibition are those who are pushing across boundaries in all of their work, so doing so in the realm of the object poem is just another way to do that pushing.

I call all of my own object poems "semiobjects" because they are semiotic objects, because they are half object and half something else, because they move like tractor-trailers through our imaginations. And all of these pieces, in some way, push us towards language, even if not to it.

Two days from now, I will be attending the exhibition opening, and the day after I'll perform with a number of others at a poetry performance. Then I'll fly back to this side of the country. I'm going three thousand miles away for the weekend. Here's the schedule:

Artists' Reception: First Friday, November 4, 2011, 5:00-8:00 p.m.

Poetry Reading & Performance: Saturday, November 5, 2011, 4:00-6:00 p.m.

Curator On Site: Saturday, November 26, 2011, 12:00-6:00 p.m.

I hear that the west coast, where I and generations of my family are from, is where the sun sets into the sea, so I'll be traveling toward sunset, which is another word for death, which is another word for sleep, which is what I'll do right now.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 02, 2011 20:13

October 30, 2011

Caution: Aution

[image error]

Geof Huth, "AUTION CAUTION" (2011)

For a few months now, I have been making poems by finding them in the world and photographing them. Possibly, the process is more complicated than that, since I'm actually photographing them with my phone using the well known Hipstamatic app. When I take the picture, I frame it carefully, and I choose the "film" and "lens" used to distort the found image in various ways.

To many, the results wouldn't be poetry at all, but to me these small poems are simple yet expressive works that question the limitations of poetry and engage not with language as devised by the poet, but with texts and near-texts found and manipulated by the poet. I see this as a most direct way of responding to the world around me, by simply capturing it.

I probably have something like 100 of these poems now, and 46 of these appear in my newest book, AUTION CAUTION . Just out from Redfoxpress, this book is number 63 in the press' "C'est Mon Dada" series. There are three ways to purchase this book: 1. Purchase a copy directly from the publisher at this link; 2. Buy it via Amazon.co.uk; or 3. Purchase it at Printed Matter in New York City (once copies arrive there sometime in the future).

Here are the details for this small book, small enough to fit in a hand:

Geof Huth, AUTION CAUTION

Nr. 65 of the "C'est Mon Dada" collection

A6 format - 48 pages - laser printing.

Thread and quarter cloth binding

November 2011

€15 euro / US$20 / £13

ecr. l'inf.

For a few months now, I have been making poems by finding them in the world and photographing them. Possibly, the process is more complicated than that, since I'm actually photographing them with my phone using the well known Hipstamatic app. When I take the picture, I frame it carefully, and I choose the "film" and "lens" used to distort the found image in various ways.

To many, the results wouldn't be poetry at all, but to me these small poems are simple yet expressive works that question the limitations of poetry and engage not with language as devised by the poet, but with texts and near-texts found and manipulated by the poet. I see this as a most direct way of responding to the world around me, by simply capturing it.

I probably have something like 100 of these poems now, and 46 of these appear in my newest book, AUTION CAUTION . Just out from Redfoxpress, this book is number 63 in the press' "C'est Mon Dada" series. There are three ways to purchase this book: 1. Purchase a copy directly from the publisher at this link; 2. Buy it via Amazon.co.uk; or 3. Purchase it at Printed Matter in New York City (once copies arrive there sometime in the future).

Here are the details for this small book, small enough to fit in a hand:

Geof Huth, AUTION CAUTION

Nr. 65 of the "C'est Mon Dada" collection

A6 format - 48 pages - laser printing.

Thread and quarter cloth binding

November 2011

€15 euro / US$20 / £13

ecr. l'inf.

Published on October 30, 2011 20:36

October 28, 2011

3 lines = haiku

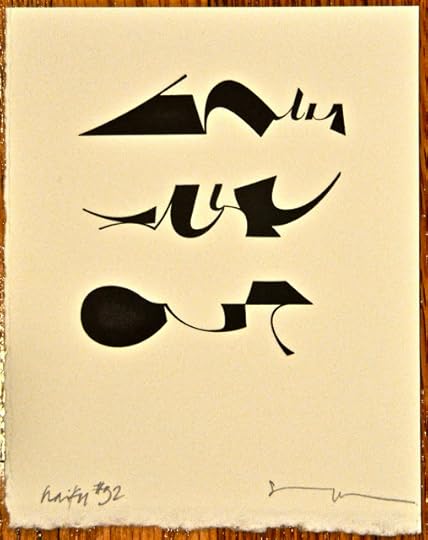

Scott Helmes, "haiku #92" (2011)

Scott Helmes, "haiku #92" (2011)On Scott Helmes birthday, which was yesterday, I received this print from him, which reminds me that I never send him gifts, though he sends them to me.

It is a small gift, but dear. Scott has spent years perfecting his technique, and he is one of the great artists in the world of visual poetry. This work is a word of textual abstraction.

Into it, Scott has assembled a number of fragments of letters, which he has put together into shapes that resemble words, but unreadable ones. It is the beauty of these shapes, how they fit together as if they were always one, and how they mimic writing without ever seeming to be writing that makes this a great poem.

These shapes are pressed deeply, and in a pure black, into the cream sheet of heavy cardstock. This poem is a physical even. Would that all visual poets could be so talented.

I am tired from a long week and a long night and will head off to bed soon, but to bed with a mind filled with these unreadable words.

I realize that I don't even mind Scott's beautiful signature, maybe because it is as unreadable as his text. Maybe because it is outside the true frame of the piece itself and it doesn't destroy the mise en page of the piece. Maybe because I love beauty.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on October 28, 2011 22:03