Geof Huth's Blog, page 20

November 30, 2011

Coming back up for Air, I Realize I Haven't Drowned at All

Three Boxes of Publications, Most Acquired This Year (30 November 2011)

Three Boxes of Publications, Most Acquired This Year (30 November 2011)I took notes for this, so I have to get it right.

At best, I am Frank O'Hara. Can I be Frank? At worst, I am Frank O'Hara. I came up with the title for this constellation of words while foldering poetry pamphlets and magazines and arranging them in boxes in alphabetical order. I have filled three boxes so far. I will fill at least one other, and maybe more. Estimating is the art of being wrong but vaguely sure of it. We depend on what we don't quite know.

When I came up with this title, I first thought I should make a poem out of it, a poem to go under it, with it. But I thought better, deciding that this title needed to be the title of a little essay to end the night I'm struggling through with pencil and folders.

I made all these notes about what I was going to write, and my handwriting is somehow appealing to me. I like how it is long and thin, a bit messy, and occasionally stylish. Not good handwriting, but serviceable. (Like this is not good writing, but serviceable.)

Moving through all of these publications reminds me that I have failed at doing in this space what I had wanted to do: to talk about poetry on the margins, poetry that makes its value in the margins, poetry not much cared for but all the more special for exactly that reason. I have a little pile of books to write about, some that I had read at the beginning of the year, and yet I've set down no words about them. And I wondered why. I didn't wonder what my excuses would be. I know those well enough. I wonder how I let this happen.

And the reason was simple and clear: I am a failure poet, a poet of failure.

I've written about this before. I've suggested that failure is not only an option, that it might be a preferred one. Why? Because success is fleeting, at best, and usually not found—because it is the work that matters to me. I don't put much effort into publishing what I write. My energies, such as they are, I focus into writing, into making. Call me Fabbro, or even ffabbro. My focus is making, not distributing. If I write a book, I might send an electronic copy of it to a few friends, but only if it's reasonably short. No-one's read the book of 156 longish poems I wrote a few years ago. Plenty of my poems have entertained only me.

Since we could reasonably argue that poetry is meant to be consumed by others, that success is other people (other people knowing one's poetry), I can claim, without fear of contradiction, that I've failed at being a career poet. I am not unknown, and I don't bemoan the fate I've created for myself, but I have to accept that most of my poetry is a big secret to the world. The other day I prodded Douglas Rothschild into saying this about the reading he was planning to set up for me in New York City: that he wanted to have my friend Chris Funkhouser be there to be the "name poet." I have to say that I really love that.

I have amassed a full cubic-foot box of poetry I've written this year alone, yet I don't think I've published any poems this year, except a few found photopoems in Otoliths, one poem in the book The Bury Poems, and a small book of photopoems put out by Redfoxpress of Ireland. (I'm not counting the little publications that I create for each reading I give.)

These papers of mine, and all these publications I've made my way through this year remind of more than my failure as a blogger about marginal poetry and a career poet (though I'm not saying I'm a failure as a poet, just that I care about something else; I want more to leave something behind than to have people see it now). This detritus of my life reminds me that I am a person hungry for experience, hungry for media. I want to watch every movie and read every book. And this consumption is a kind of craziness.

I'm estimating that I'll donate about 80 boxes of dictionaries and other wordbooks to the University at Albany this year, along with another 10 boxes of my papers. Why do I have so much stuff? Because it is matter that matters to me, because each book represents knowledge.

The one with the most words at the end of the game wins.

But the game is ending for me. I'm in love with the book, as a physical object, as a carrier of meaning, as a dear friend that opens herself up to me whenever I need her to. I thought, maybe, that I couldn't shake this, but I can. I'm holding onto thousands of books, and still more boxes of my papers, but this year will be my greatest divestment of stuff ever, of the stuff of meaning, and meaning is all that I'm about. (Max Richter's "On the Nature of Daylight" is playing while I write this, because my life needs a soundtrack, and because this is the right soundtrack at this moment.)

I am giving up my books and my papers because I age faster than most people. I feel in my body as a child. Everything is a pleasant surprise to me. I am still energetic enough (and I'm not that old at all). I am still enthralled with the pleasures of the earth. The book and the word entrance me because they are about meaning, but also because they are bodily forces. With them, through them, I return to the body, which is the source of poetry, because poetry is life, because the body is life.

But we, eventually, have to give everything up, we can hold onto nothing forever, and I want to give things up at my pleasure, I want to give them away before they become a burden to me. I need a lighter life. Not a weightless one, but one that is nimbler than mine is now, one of a couple thousand books instead of five thousand. I want to read my way through all my cheap paperbacks (Faulkner, Borges, Smollett even), and I want to discard them, give them away to someone else, start a new life for them.

I want to be filled with them without having to have them. I want the memory of a life instead of the life that these books were. But those most important markers of my life (these personal papers of mine and this huge collection of wordbooks) I want held together as a piece, as a memory of me, just as I will carry within myself a memory of them. So I'm keeping them together. Sometime soon there will be nearly 200 cubic feet of materials that carry the DNA of my thought, words and images and sounds that maintain a better memory of me than I do myself.

I have created this world of meaning, thus I can give it a new way to mean, and a new place in which to do it.

More than a week ago, I fell while walking up the stairs with two heavy boxes of papers and books. The weight of the paper in my two arms (which hugged the boxes to my body) pulled me forward and into the stairs I was walking up, and my left thigh smashed against the corner of a stair. My leg was in pain for hours, so I had to sleep with the pain, but it resided quite a bit. I did not bruise, not for a week, and then the other day a huge bruise, deep and purple but also greenish, appeared on my inner thigh, obliterating this diffuse pink birthmark that otherwise rests there. My entire leg is now sore, sometimes remarkably so. A sharp heat impedes my walking, and I remember that we cannot ever escape the past or what we have done there.

So we might as well preserve what we can of the past somewhere, so we can visit it, and see what we are like. And that's what I'm doing by putting together all these boxes of meaning, which are not less (and nothing more) than my message to the future.

And not all futures are distant.

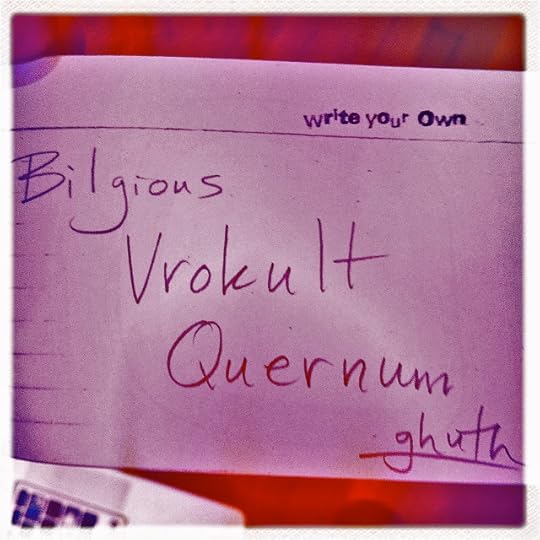

Geof Huth, "Bilgious" (a poem written in a book of neo-Dada poetry tonight, 30 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "Bilgious" (a poem written in a book of neo-Dada poetry tonight, 30 November 2011)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 30, 2011 19:17

November 27, 2011

The Poetry Survives, the Books at Least

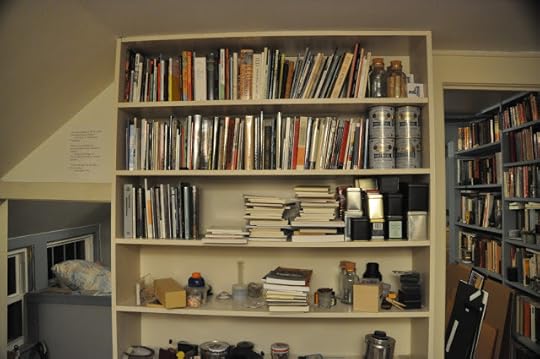

Geof Huth's Poetry Collection (22 November 2011)

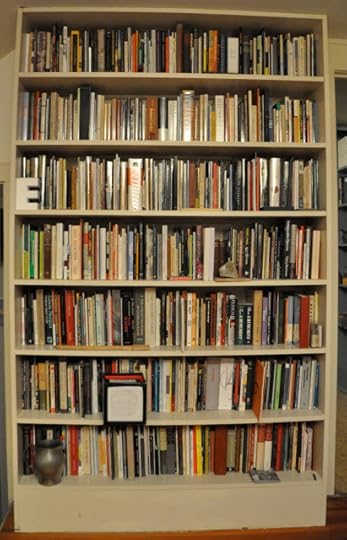

Geof Huth's Poetry Collection (22 November 2011)I cannot buy any more books of poetry.

That is what I tell myself, but I ordered a few titles from Jeffrey Maser of Berkeley just the other day. The problem is that the bookshelf that I've set aside for poetry (one that my father-in-law built into a wall for me) is absolutely full. I might be able to squeeze another book into it, but it will be difficult. This bookshelf includes only books of poetry by individual poets or sets of collaborators. There are no anthologies here, no books about poetry, no books by poets that I don't categorize as poetry (all of these are on a different, much smaller bookshelf).

This set of shelves holds my entire alphabet of poets: Aasprong to Zukofsky. But the truth is that not all my books of poetry by individual poets are here. A number of books that are too large for these shelves, or too small, or which are out for reading, or which are set out in anticipation of reading, all of those, lie on other bookshelves, and they number certainly at least 250 books. These shelves here hold about 650 books, almost 100 per shelf, some very thin, some quite wide.

So I assume I have about 900, but maybe even 1,000 books of poetry, almost enough to have to divest myself of this collection as I am my dictionary collection (another 2,000 books there).

I'm not sure if books in such numbers are a burden or a blessing, but I assume they are both. I'm withholding at least 20 dictionaries from my donation to the University at Albany, because I can't bear to without them yet. I'm holding onto all my poetry, except for chapbooks and poetry magazines I've already read.

Yet every book will have to go at some time. As I wrote, elsewhere, today, "Everything must die, and one's connection to a dictionary [or any book] may be the least of such deaths. "

Maybe the least, but still something a bibliophile feels acutely.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 27, 2011 20:59

November 25, 2011

The Re-invention of Hugo Cabret

Geof Huth, "The Blue Bird of the 72nd Street Subway Station" (25 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "The Blue Bird of the 72nd Street Subway Station" (25 November 2011)One day shy of four years and four months ago, when I was still an innocent child, I wrote a review of "The Invention of Hugo Cabret" in this very space. My review was positive, though I certainly characterized the writing in this illustrated book as just a little better than dull. But it is not only words that make a book work, sometimes it is also images, or how the images work with the words.

This afternoon, I saw the movie Hugo, based on the same book but retitled by Hollywood, which believes the more uninteresting a title is the better one will be able to promote the film. Directed by Martin Scorsese, this film hews closely to the story in the book (though Hugo peers from the 4 in a clock instead of the 5), and (more importantly) it maintains the books "second act" focus on Méliès and silent film in general.

Since I the time when I'd read the novels, which is now a lifetime ago, I have seen scores of early silent films, at least doubling the number I had seen up until that time, so every snippet of a film that flashed before my eyes was a bit of a film I actually recognized. I had that connection to the predecessors of this film. And so does Scorsese. At his core, Scorsese is not a filmmaker; he is a film fanatic, an historian. And this film of his is both an authentic and moving replication of the original verbo-visual novel it's based on and an homage to a style and era of filmmaking that we have generally abandoned. The act of making this film is an act of restoring our memory of the mute films of the past, and this resonates with the story of the film itself. The film as a project, thus, recreates the book as a project and the book as a story.

Which is perfectly right, since no film is actually about itself (unlike, say, poems, which are usually about themselves); they are always about something else; they are always replicants standing in for something else.

So I watched the film in 3D, at a theater near the 72nd Street subway station in Manhattan, and I was amazed at its artistry, its sense of magic, and it all reminded me of how the now clumsy special effects of Méliès were actually acts of supreme genius. He thought beyond the film stock, and so he figured out how to make appear on it what was never quite there.

This film reverberates with the past: the past of Paris, the past of cinema, the past of the characters occupying that pseudo-3D space before my eyes, and the past represented by the book fewer people will read than will see the movie (even though that thick book is a quick and beneficial night's read). But it is also a good story well told, with characters that are much more real than those of the book. Here, rather than in the original book, the people become real flesh and blood, beings we can believe in and care about, even the station master. So I teared up, because I am a sap and my heart runs slow though steady, near the end of the story when Hugo Cabret begs the stationmaster to let him go, because the stationmaster should understand, and the stationmaster knows Hugo is right, and knows that his only chance is also Hugo's: that he has to let him go.

And so the trick of caring for a celluloid person works on me, because I want to replace the clockwork of our lives, no matter how efficient and effective, with the beating heart of a body, because it is better to care at all than to wait until it is the perfect time to care. So I would tell you, if I could tell you directly, to see this film, because it is beautiful visually, because the actor's make themselves fragile and real, because Scorsese makes a Hitchcockian camio, because the special effects are perfect because they are unobtrusive and propel the story, because the clockwork automaton who draws us and the characters themselves into the story has a real beating heart that we can never see.

And I say this even though I can never understand why Hollywood usually thinks that all foreign languages when represented in English on the screen need to be presented with British accents, instead of American or Canadian ones or the accent of the languages people are actually supposed to be speaking.

There is, I suppose, nothing real about the movies, and nothing real about the hearts we discover we have while sitting in the dark to watch them.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 25, 2011 20:06

November 24, 2011

da levy died today

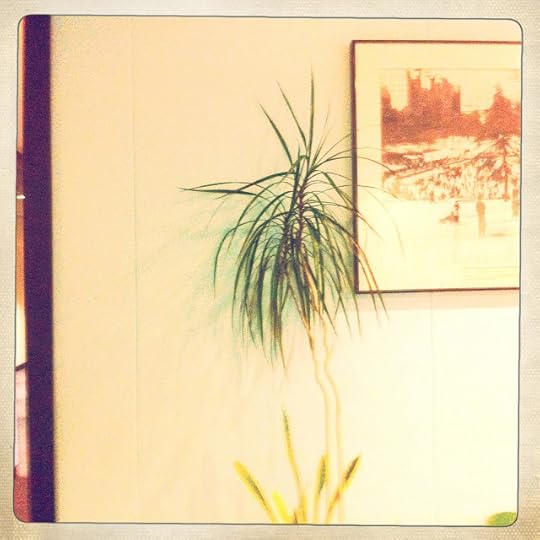

Geof Huth, "How the Tropical Survives the Winter of Dreams" (Albany, New York, 23 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "How the Tropical Survives the Winter of Dreams" (Albany, New York, 23 November 2011)A dream is not a portal to the soul; it is, instead, the soul itself. A dream does not so much tell us something about the dreamer as it is the dreamer. Sometimes, we realize that we are merely ourselves, that the features that distinguish us from others are inseparable from ourselves, that we are just an accumulation, rather than a whole. These features of thought and personality and inclination are like our million physical traits: the color of our eyes, the shape of our fingernails, the fact that our second and third toes are longer than our big toe, or are not.

I dream in spurts, never sleep solid for long. I am awoken, almost always without knowing it, by the gasp of sleep apnea, with a gargantuan and supposedly frantic gulping of air. My nose has been broken, septum deviated, since I was two and a half (the consequence of a little girl pushing me down a set of metal stairs in Albany, California). The inner workings of my nose also shrink during the course of a day, opened up only by a couple of sprays into each nostril in the morning. I can breathe through my nose during the day, and sometimes only with concentration, but at night only my mouth takes in oxygen. My mouth goes dry from in during the dry insideness of winter. I try to eliminate my waking from apnea by sleeping on my side, hand unconsciously stuffed under the pillow to give it loft, and the weight of my body on my wrist and at my elbow helps create the carpal tunnel syndrome of hands, gives the crook of my right arm a permanent aching.

So I do not sleep well, yet I still dream in some depth. I wonder, sometimes, if a dream that seems to last for fifteen or twenty minutes is just a few seconds in length, if the chronological reach of a dream is faster than that of waking life, if that is why I can accumulate the dreams that are me as quickly as I do.

I dream of art that doesn't exist, such as one that I remember from this morning.

A large white cabinet, but made of metal and painted white, faced me. It was wider than it was tall, yet taller than I, and it had two doors next to each other, both of which swung on hinges attached on the right. It reminded me of a refrigerator, but I'm not sure if it was.

Somehow, through the diplomacy of dreaming, I knew that this was an artwork created by da levy, the 1960s radical poet, visual and otherwise, who is one of the great visual poets of this country, and who killed himself at age 26, forty-three years ago today. (I find it strange that I dreamt about his work, though not him, today, on the anniversary of his death, even though I had no recollection that today was his deathday).

I opened the left door to the artwork, and a number of cylindrical tubes fell out of the contraption. These tubes had stopper in their openings and words on the sides. They were formerly the container of some kinds of chemicals or medicines, and levy had assembled them so that the strange tradenames on their sides would congeal together into a poem we could read at random. There were many other items in this side, some hanging from the top, and many reaching back to the back of this cave, but I was too intent on picking up and re-placing the cylinders to pay much attention.

Next, I opened the right-hand side of the container and I noticed an herb, I'm not sure what, with cordate leaves hanging from the ceiling. These were not just leaves, I soon realized, but plants still growing, even in the dark, decades after levy had placed them inside here. While I was examining the leaves, knowing at the time that they were edible, two snakes slid out through the doorway and away. I was prepared to ignore them for a bit, but my companion, an agitated man who seems to have been my brother Rick, pointed out the fact of their escape and urged me to catch them. He was worried they would cause some damage to someone, so I closed the door and never examined the rest of the flora and fauna stored there.

We went off in pursuit of these two snakes, which were fat vipers, their triangular heads giving them away. They slithered up a small rise and under a wall. At that point I realized that, though there was dirt and grass under my feet, we were inside some huge building, but one filled with plants and, likely, animals, so this wall merely separated two rooms in this giant terrarium.

There was no door through this wall, so we had to pull the wall apart. We began by pulling the bark off the walk, for it was covered with bark, and what we found underneath surprised us. It was apparently living flesh, not human though. As we pulled more and more bark off, we realized we were uncovering the flesh of a giant whale and that the room we would be moving into was the body of a whale. We wondered if we could eat this flesh and how the whale stayed alive or its flesh stayed fresh after so many years being in this place.

After much work, we peeled the flesh off the framing of a wall and entered a room that was dark and moist. We found the snakes off to the right edge of the room, still moving up a slope, but more slowly now. I knew I had to catch them, and I knew I had to be careful while doing so. I headed to the left to find towels I could use to catch the vipers teeth in and to wrap their heads and hold them safely in place. I realized then that I was in the attic of the building we were in, that there was a window at the far end letting some light into the room, and that I had to move carefully over the weak floorboards.

I was looking up into the rafters when I awoke from the dream, thinking that I would never know how the dream ended, as if there were a predestined ending to the dream, as if any dream has a clean end that resolves a clear story. It's likely, though, that I would have remembered none of this dream ever again had I not awoken.

While writing this down, I also realized that two Albanys bookend my life, and they are separated by a continent. That continent is my life.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 24, 2011 06:37

November 20, 2011

rT

The ligature is an obsession of mine.

A ligature is a sewing-together of two separate letters of the alphabet. Its goal is to make more eye-appealing those pairs (and sometimes triplets) of letters. The ligature brings two letters closer to another, makes them a single character, so that they might sit more comfortably in a line of text.

For instance, the common ligatures, the fi and fl, fuse the opening eff to they eye (removing the tittle in the process) and the l. These are such natural characters to our eyes, that when they are not in place in a printed text our eye feels the difference, even sometimes when we don't consciously note that fact.

But other ligatures are rare, even the ct ligature, which once was common but fell out of practice years ago. The way these lost ligatures fused two letters together became too ostentatious for us, so we dispensed with them.

Though sometimes the process of moving forward is a process of moving backwards to older ideas.

So Cartier, well known for having a logo that joins all the letters of its name together cursively, and a jewelry enterprise that is known for the showy, put together a little ad campaign for this season, now upon us, of buying. And the campaign is called Winter Tale, not A Winter's Tale, not Winter's Tale.

There is something a bit awkward in that title, just as there is something a bit awkward in the ligature formed between the last letter of the first word and the first letter of the last word.

The r and the T are brought together in a gaudy, yet breathtaking way. This is the ligature as an act of visual defiance. It is not there to make the words less obvious to our eyes, not there to disintegrate into the background, into the mere sense of the words. It is there to make us see this ostentation, there to make us look with our eyes, because we are meant to see the jewelry that comes with this ligature.

This ligature is strange (and thus almost awe-inspiring) in a number of ways:

It joins together letters in separate words

1. It joins together a minuscule and a majuscule letter

2. It begins with the minuscule letter and ends with the majuscule

3. It fuses the two letters with a swoop (making it a throwback to the ct ligatures and others of its kind)

4. It joins the letters together clumsily at both ends:a. the curving and lowering arm of the r is sent backwards, around, and up in a loop toward the T

b. the flat arm of the T accepts the loop, after a bit of widening in that loop, into the middle of the head of the T as if it were an extension of the downward stem of the T.

This ligature is quite a remarkable feat, and probably quite appropriate for the use it has. Though it's still a bit of a typographical gryphon, a beast we can imagine but one so bizarrely constructed we might never want to meet it in person.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 20, 2011 11:31

November 18, 2011

Words, words, words; Books, books, books

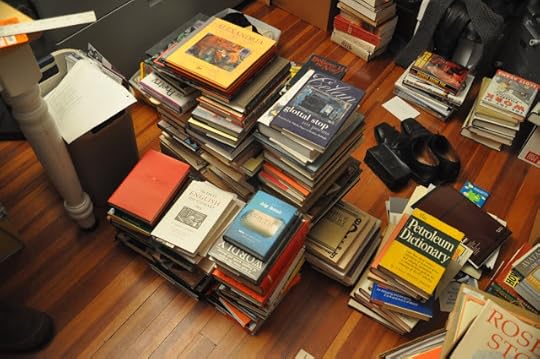

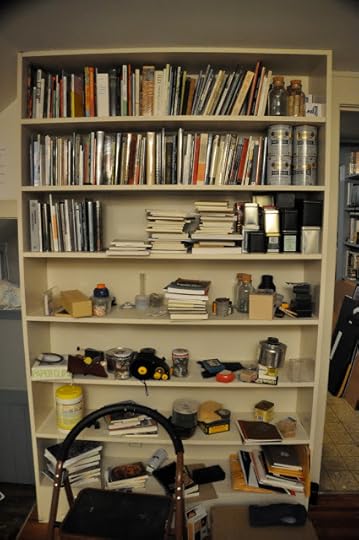

The Pile of Boxed Wordbooks

The Pile of Boxed WordbooksI have to stop for the night, but I can't make myself stop, and it's almost 2:00 am as I begin this.

For years now, I've been simplifying my life, removing stuff from around me. Eighty cubic feet of my papers, all that documentation of my life, at least one item for each year (and usually hundreds). Here and there, I'm throwing away toys, furniture, whatever, that I don't need anymore. Now, I'm pulling a bit more than 1,000 of my books to give to the same library that holds my papers.

What I'm disposing of, what I'm holding together as a huge unwieldy collections, are my dictionaries, thesauri, grammars, and other books about language, writing, words. These books form the core of my intellectual interest (language), and I am a little unwilling to give them up. But I need to make space in this house. Most of the house is fine, but this area that is my domain remains a bit of a mess. There are probably 100 boxes here filled with books, paper, supplies for creating objects of word and image. Something has to give.

Books Awaiting the Wrapping of Their Dust Jackets I am so obsessive about creating order, that I'm making shaky piles on the floor of all those books whose dust jackets I have to cover before I donate them to the University at Albany. This pile here shows that my interesting in language is broad: a dictionary of terms from the petroleum industry, two books on "dirty words," and a reprint of the first dictionary of the English language. My earliest dictionary is about 150 years younger than Cawdrey's. What you can't see in this picture are my large collections of anti-dictionaries (like Ambrose Bierce's Devil's Dictionary) and slang, including many books that are quite old. Yet lots of the collection are very new, and even in paperback. If the book is about language, I wanted to buy it. Monograph of the language of the Isleños of Louisiana? I have it. For now.

Books Awaiting the Wrapping of Their Dust Jackets I am so obsessive about creating order, that I'm making shaky piles on the floor of all those books whose dust jackets I have to cover before I donate them to the University at Albany. This pile here shows that my interesting in language is broad: a dictionary of terms from the petroleum industry, two books on "dirty words," and a reprint of the first dictionary of the English language. My earliest dictionary is about 150 years younger than Cawdrey's. What you can't see in this picture are my large collections of anti-dictionaries (like Ambrose Bierce's Devil's Dictionary) and slang, including many books that are quite old. Yet lots of the collection are very new, and even in paperback. If the book is about language, I wanted to buy it. Monograph of the language of the Isleños of Louisiana? I have it. For now. The Installation of My Poetry Collection in One Place

The Installation of My Poetry Collection in One PlaceAs I'm packing up my dictionary collection, I'm unpacking parts of my poetry collection and beginning to move all poetry into one room. Because I feel a need to alphabetize as I go, the process of shelving these books is slow, but interesting. Anselm Berrigan rests just to the left of his father Ted, but the mother of the family, Alice Notley, rested near her men only briefly before I had to move her to the second shelf. Tom Beckett rests beside Samuel Beckett. Deb Poe is next to Edgar Allan Poe, something I'd never considered before (that the two of them have the same surname). Bob Grumman rests between Robert Grenier and Gabriel Gudding. And why do I have so many duplicate copies of books by Ron Silliman?

The Entire Bookshelf

The Entire BookshelfLuckily, the shelf I'm using to store these books of poetry has plenty of other shelves. And if I run out of space here, I can start using one of the two other built-in shelves. I have plenty more poetry elsewhere, so I'll need the space.

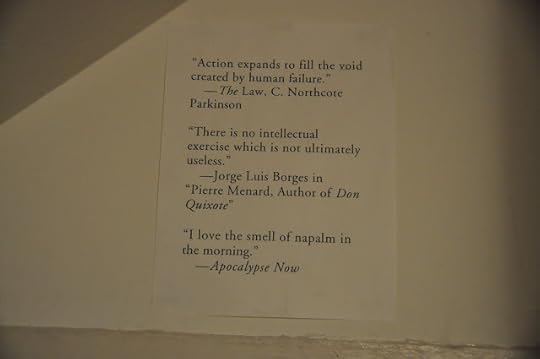

The Quotations that Overlook My Office-cum-Library-cum-Studio (AKA the Third Floor)And as I work, I sometimes notices these quotations that I've posted over the door to the downstairs, because these are the words that guide my life.

The Quotations that Overlook My Office-cum-Library-cum-Studio (AKA the Third Floor)And as I work, I sometimes notices these quotations that I've posted over the door to the downstairs, because these are the words that guide my life.ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 18, 2011 22:20

November 17, 2011

Suddenly: Exhibition

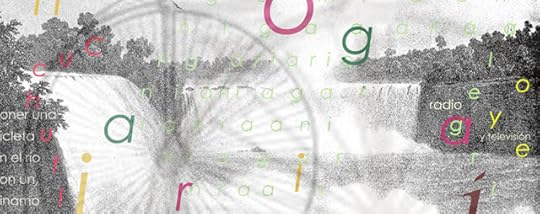

Loss Pequeño Glazier, La Cuchufleta (2010)

Loss Pequeño Glazier, La Cuchufleta (2010)Not through any of my normal sources of information, but through a former colleague from the New York State Archives, I learned tonight that I, and what appears to be hundreds of others, are included in a large visual poetry exhibition, Language to Cover a Wall, at the University at Buffalo. The exhibition runs from November 17th (which I'll note is today) until February 18, 2012. Some of the events below are already in the past, but I'll note them anyway.

Lecture: "jw curry's Exemplary Archive"

Marvin Sackner is co-founder with his wife Ruth, of the Sackner Archive of Visual and Concrete Poetry, which holds collections of visual poetry from more than 50 countries, including an archive of work produced and collected by avant-garde Canadian poet, publisher, and bookseller jw curry. (This lecture was tonight.)

Performance: Sound PoetrySound poetry performance by internationally acclaimed Canadian sound poets Paul Dutton, Nobuo Kubota, and W. Mark Sutherland. (This performance was also tonight.)Exhibition: Language to Cover a Wall: Visual Poetry through its changing media November 17, 2011 - February 18, 2012 LANGUAGE to Cover a Wall abounds in visual and concrete poetry, in which the visual arrangement of text, images, and symbols combine to create an intended effect. This alternative to standard linear poetry occupies a space between poetry and visual art but some of it — "intermedia" poetry — blurs the distinction between writing, graphic art, video, dance, music, and digital media.

The exhibition demonstrates the dramatic shift successive new media have brought to the concepts and definitions of poetry. The exhibition curatorial team (Steve McCaffery, David Gray Chair Professor of Poetry and Letters, UB Department of English; Karen Mac Cormack, adjunct professor of English; and Michael Basinski, Curator of the UB Poetry Collection) seeks to increase awareness of concrete and visual poetry and its ongoing possibilities. An historical range of works by George Herbert, Lewis Carroll, Ian Hamilton Finlay, Barbara Kruger, Henri Chopin, Robert Lax, Dick Higgins, Daniel Spoerri, Alison Knowles, d.a. levy, Bob Cobbing, Siebren Versteeg, bpNichol, Bill Bissett and Guy de Cointet are among the three-hundred plus works on view.

A "Digital Poetry" component curated by Loss Pequeño Glazier, Professor, UB Department of Media Study, will be presented in the Second Floor Gallery, Center for the Arts. It brings the traditions of visual poetry into present day digital poetics with an emphasis on sound, video, and language, most often using computer process media practices. These practices include works in a variety of formats such as computer-generated poetry, time-based works, language and video, and digital poetry and dance. This exhibition shows new works alongside rarely exhibited historical works crucial to the field, presenting some of the most highly celebrated digital poets from the United States, Canada, France, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Spain, Austria, Sweden, and Norway.

<i>ecr. l'inf.</i>

Published on November 17, 2011 20:31

November 16, 2011

A Bridge of Words over the Water

A. symbol of a symptom

that

a simple syrup that a

single

what a single simple symptom

could

make a cymbal into symbol

so

there might not be a word

to

might not be a word to

make

not be a word to make

into

be a word to make into

sense

B.efore

the way it all came

how

it all came right out

how

in pieces it came out

how

the words they said and

how

the words they heard and

how the words they also

understood

how they infected them as

thought

C.onsidering the way

they first broke

the way they

broke into words

the way they

repeated them out

the way they

fractured them first

we could see

the frantic in

the frantic in

how they were

the frantic in

how the words

in how the

words were them

D.ear little words

in the ear

sweet little words

in the ears

in the ears

then they break

from a sweet

little word come

a sweet little

word come in

and they would

break as if

they would break

as if they

as if they

were just words

F.or they

Would eat the words

into pieces

they would eat them

and they

would break like words

would break

like all words said

break back

into piecesof words

and then

they would eat through

eat right

through the mouths of

the others

saying those broken words

or others

not saying those broken

words but

they would eat right

they would

eat right through them

eat right

through their mouths until

they were

dead and until they

were dead too

were also dead

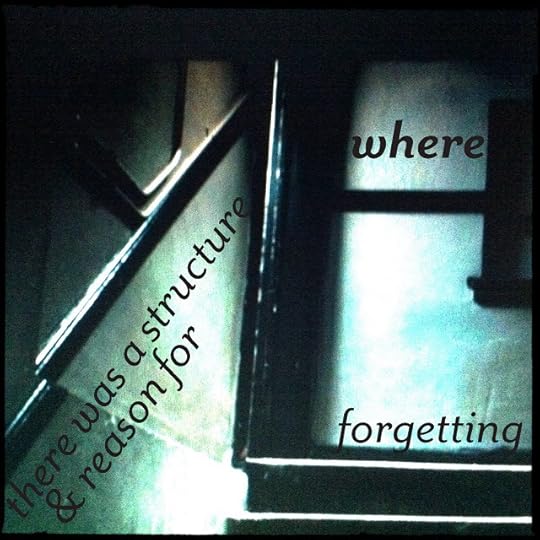

Geof Huth, "where / there was a structure" (16 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "where / there was a structure" (16 November 2011)ecr l'inf.

Published on November 16, 2011 19:43

November 15, 2011

Bridge to Terra Firma

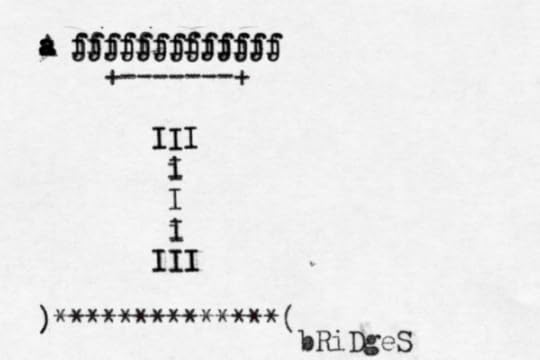

Geof Huth, "Aa fjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfj" (14 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "Aa fjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfjfj" (14 November 2011)The connections are slender and brittle, but I can bridge them.

We believe we can.

A text is a visual presence. The particulars of its making set the particulars of its form and telegraph important messages to us. If an ancient manual typewriter is used, the text will show certain irregularities. These qualities may, these days, be seen as endearing, even tending toward the handcrafted.

Even these poems may seem so, though I created them on my iPhone.

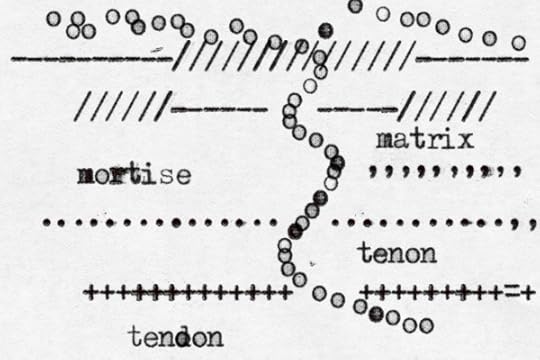

Geof Huth, "mortise/matrix" (15 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "mortise/matrix" (15 November 2011)The methods of production change, though not as much as the production. I see in these works, though each is different from the others, certain visual and verbal (maybe even verbo-visual) tendencies of mine. Excepting asemia. Each of these has words.

But each of these means in different ways. The top one is about the bridge out to reality that any I makes and the complication of the I (thus the complication of reality).

Who will see that? Even after I point it out, who will believe it?

A writer's job is to lie. A reader's job is to be deceived.

(I was supposed to be writing about an exhibition today, but I ended up typing poems on my phone. It was a slightly tedious job, though also slightly exhilarating. The inability to correct any errors in this process made errors part of the message.)

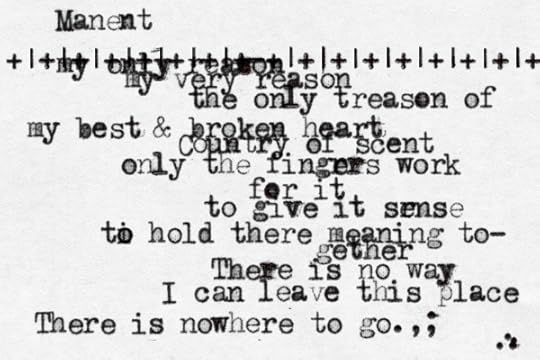

The middle poem is about how things fit together. I wanted to call it "Manent et Exeunt," but I'd already used "manent" in one of these poems early this morning, just after midnight:

Geof Huth, "Manent" (15 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "Manent" (15 November 2011)Nothing, of course, fits together, or it fits together messily, imbrications of thought and direction.

This last poem is governed by pun and rhyme, by sight and sound, by the power of punctuation. It is a poem of sentences. The second is a poem of words. And the first is almost a poem of one word. Many will see only one word in it, but that is the word of lesser importance.

I am governed by what I cannot escape: I.

Even as I make these poems, I wonder what they are.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 15, 2011 20:23

November 14, 2011

who i am is sleep

Geof Huth, "who i am is who" (14 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "who i am is who" (14 November 2011)There is no clear structure to thinking. Everything is held together in our minds by a web of webs, and there is no knowing where one strand may hold onto another, just right, to allow a thought to pass, an idea to come.

That is why Jack Spicer knew the Martians came and left the ideas in his skull. He could not imagine what he could imagine. He could only imagine it into being.

There is not necessarily a connection between a picture and the words we place upon it (or between words and the picture we put behind it) but proximity makes it so.

We are animals of connection ("Only connect!"), and we yearn for pattern and purpose for the images that blaze before us. And then die away.

Some say that the world of text has left us, that we are multimedia now, returned to the senses, without need for the encumbrances of our coded symbols, now so ancient.

But it is not at all so. We are more dependent on the text. Sometimes it tells us what we're seeing. Sometimes it tells us who we are.

Yet the image might not seem connected to the text, even though the first generated the second. Yet not every text that captions an image is a caption.

Sometimes text and image live in limbo, neither greater than the other, neither more necessary, neither particularly connected to the other. Yet both always completely intertwyned, intermyngled, intertwyngled.

How do you separate the image from the text? (With a crowbar.)

As the crowbar flies through the air, so do our thoughts move, one to the next, never quite forward, but around. Every thought is swallowed into the body, which action is a kind of flushing.

Every thought is flushed out through the bottom. What washes through us is experience. We hold onto it for a while, but nothing is forever.

Sometimes, if we could pay for it, we would ask for the world to be remade, so we could see what it all means.

But then we remember that the meaning makes the most effect upon us when it seems a little off, when the thinking of someone else (even through the artifacts of text and image they leave behind) causes thinking, even very different thinking, to course through our own bodies.

Sometimes we think that coursing is the movement of blood or breath, and we imagine that we are still alive.

Geof Huth, "light is the only kind of wind" (14 November 2011)

Geof Huth, "light is the only kind of wind" (14 November 2011)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 14, 2011 19:01