Geof Huth's Blog, page 12

May 17, 2012

That is Why We Love Washing Machines

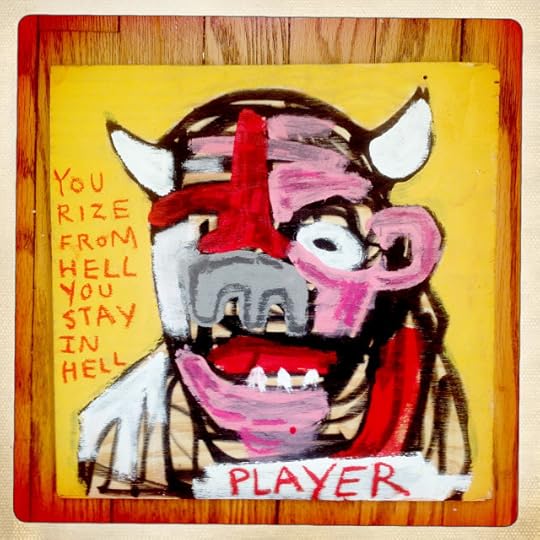

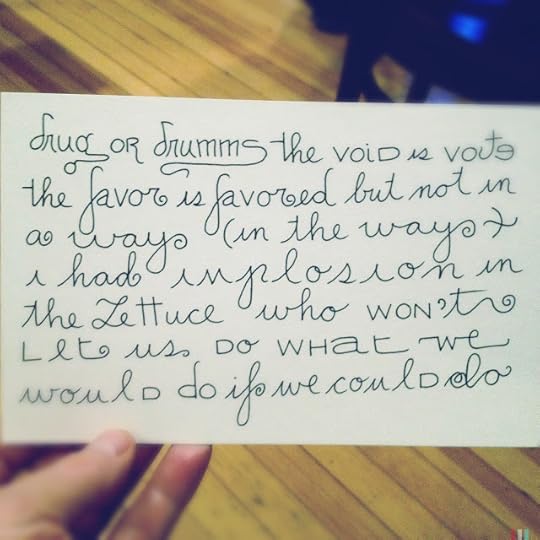

Welldunn, "Player" (4 March 2012)

Welldunn, "Player" (4 March 2012)The title is from Frank O'Hara, last year at Harvard, finally finding his voice, becoming a poet. It is almost a revelation to see it happen, something like a peeling away, it was always there yet we couldn't see it.

"I am indeciduous; I do not change," I wrote as I read all these early poems of O'Hara's. But I started writing nanopoems only while reading poems from O'Hara's last two year's of college. The voiced years. I could hear the buzzing of them, the voice coming into play.

I identify the value of poems by how they make me create something else. If the poems are good (good at least to my mind), then I write poems against their words—not in opposition to their words, but against the sound and sense and shape of their words. Some of these poems are small, some are large. The strong poems that I read make me make. They are the best inspiration, even if they produce no poem anything like themselves. As a matter of fact, that is best, that is the evidence of their value.

To arrive at the point where O'Hara was finally writing real poems, or at least the approximations of them, I had to read through almost 100 pages of terrible poems, accentual-syllabic poems where he exhibited some skill but a dented ear, goofy poems that asked nothing of the readers, poems that demonstrated his intelligence without demonstrating his skill. And the good poem is always about skill, not smarts. Our intelligence can be the driver of a great poem or the firm application of brakes upon the highway the poem rides along.

So I wonder why I forced myself through those poems, why I force myself through so much I don't like. Because, maybe, there is value at the end of some pain? I doubt it. That makes no sense in this case. Because I needed to see from what primordial mud from which Frank O'Hara arose in order to succumb to death (by dune buggy) on some dry strand's sand? Probably. Just to see that development. I read these poems to see where O'Hara came from, to hear the whispers of his mature voice in these weird displays of nascent skill and unfulfilled learning.

For the same reason, I read Robert Creeley all the way through his career, from the opening salvo, through a long and vibrant middle career, and into the steep decline of his last poems, in which he demonstrated exactly how never to use rhyme. I need to see the patterns of making. I need to see the failures along with the successes. I want to understand how the poet works even more than I want to see how the poem works. Watch the visual poet Márton Koppány to see how change blossoms.

I read these early poems of Frank O'Hara, part of his posthumous book, Early Writings, at a laundromat. I read these poems only there (hence, the title of this night's enterprise of thought). The machines would rumble around me, the clothes would tumble in the dryers, but I would read, I would read through it. On the last day of my reading, a man came off the street to say he needed a quarter for a bus ride (a ruse, a scam), so I said I'd give him a quarter, which made him say that he actually needed two quarters, so I said I'd give him a quarter. I focused on the words through the noise of machines and humans. I focused on the words.

And as I did, I sucked out of a plastic cup a frozen coffee, a frozen coffee from a body of icy slush at the bottom of the cup, but I kept reading, because I am about reading because I am about writing. Take away my words, and take away my life. Occasionally, I was thrilled by some tiny thing this young O'Hara did (a word chosen, a phrase wrought), and I looked upon these little miracles as the reason to keep reading, the reason to keep writing.

I had bought my coffee across the street, at Bonobo (a coffee shop named after the species of chimpanzee, a species of ape, sexologists had discovered, whose sexual exploits could make women sexually excited, because women were excited by any examples of sex in action, human, homosexual, primate, heterosexual, because women are excited by the idea of someone being desired, while men were more particular because they were excited by those whom they wanted to enter). While at Bonobo, I bought a verbo-visual painting on plywood by Welldunn (AKA Gregory Dunn), an Albany aritist, because the rough style and the text of the painting had entranced me:

You rize from hell You stay in hell

Oh, it is true. But read a little poetry while you're there. While you're here.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 17, 2012 20:02

May 16, 2012

Buying Poetry in Salt Lake City

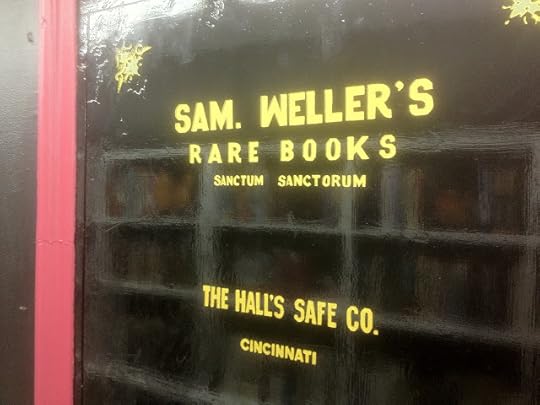

The Sanctum Sanctorum at Sam. Weller's Rare Books, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)

The Sanctum Sanctorum at Sam. Weller's Rare Books, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)Hearing "Greensleeves"* played on the lute just now, I am reminded that that is the song that the ice-cream truck would play as it traveled through my neighborhood in Barbados. Aged ten, eleven, twelve, or thirteen, I would rush out into the street that connected three of the four houses my family lived in while living on that island, and I would most likely buy rum raisin, my favorite flavor. Associations are difficult to shake. I have to force myself to think of Christmas when I hear "Greensleeves," just as I have to force myself to think of Memorial Day, almost upon us, as the onset of summer and of Labor Day, still months off, as its end.

These associations simply did not exist in my childhood. While living overseas, I had never heard "Greensleeves" in the context of Christmas, and Labor Day and Memorial Day did not exist. I have learned these associations only as an adult, so they are still forced, there is nothing natural to them. Yet they are completely real.

Back into the Darkness of Sam Weller's Books' Basement, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)

Back into the Darkness of Sam Weller's Books' Basement, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)We learn through context. We understand within contexts. This is even an important point in archives, and I spent most of my time on May 14th making this point in a workshop I taught in Salt Lake City that day. For, you see, even with archives, context is what makes a record mean. It allows it to mean. Outside of context, there is but conjecture.

I had arrived, the day before, early enough that I had had an opportunity to tour the city of Salt Lake. I visited the dramatic architecture of Temple Square, just across the street from my hotel. I climbed the hill on a hot day to tour the gorgeous emptiness of the Utah State Capitol. I walked the streets of the city, all of which were wide boulevards that extended for long long city blocks, and I saw what the city was. On Sunday, the 13th, the day I arrived, I passed a bookstore, Sam Weller's Books, that was closed, and I decided to visit it the next day because it carried used books. Life seems to hide within the used more than within the new and unblemished.

The next day, I spent a day talking, which is my only true skill. I spoke about electronic records, and it was not one of my best performances, and I'm not sure why. In part, it was because I wasn't quite the humorous person, the dramatic and humorous person I am when I'm giving a presentation. And in other part, I had the sense that I wasn't dredging up enough of my knowledge that day. It was a tiring day, fine in the end, but nothing like the days these workshops usually are. By the end of the day, I was ready to rest.

After a brief respite in my hotel room, I headed out into the city, for a walk down Main Street to the bookstore. The walk was longer than I had remembered it, so long, and coming after a respite so extended, that I wasn't sure I had the time to visit the bookstore and have dinner out before a television program was scheduled to come on TV. (Not having a television, I watch the little television I do watch on a computer, so I thought it would be somewhat pleasurable to watch a program for the first time on a television screen.)

A Reproduction of the Golden Plates Found by Joseph Smith, Sam Weller's Books, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)

A Reproduction of the Golden Plates Found by Joseph Smith, Sam Weller's Books, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)The bookstore was much larger than I'd thought it was. It took up three storeys in the building, and the floors extended much further than I had imagined. At one point, at the basement level, I found myself at the edge of an unlit section that extended back into deep darkness and was filled with boxes of books to the edge of my vision. Over all, the bookstore was a disappointment. It held many books, but few of interest, and many duplicates of exceedingly common or boring books. The poetry section was one of the largest I had ever seen in a bookstore, yet it was decidedly the worst. The bookstore's strength, and it was a significant strength, was in books on Mormonism. The stored carried hundreds of old and rare Books of Mormon in various languages and plenty of other books. With that focus alone, this was a great bookstore.

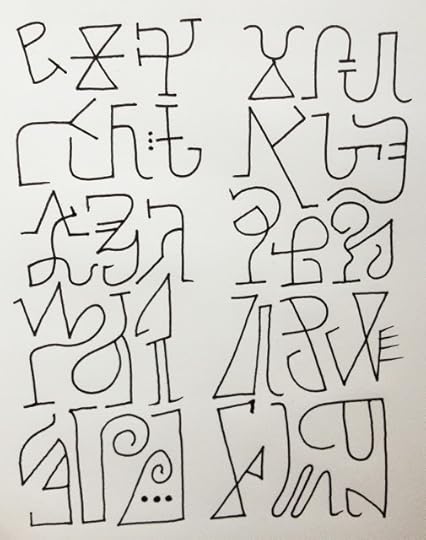

Unfortunately, my interest in such books is quite low. But I was tempted by the replica of the golden plates lost by Joseph Smith. I noted, on the one visible page, that the plate had been covered with the symbols Smith had created and claimed he had copied from the golden plates before their mysterious disappearance. What this book is, this replica (that is), is an extended piece of asemic writing meant to represent the Book of Mormon without being anything like it at all. I would have loved to have reviewed all of its pages.

Otherwise uninterested I found myself perusing the thousands of books of poetry at Weller's. The selection included multiple books by Susan Polis Schutz, a greeting-card poet of some renown. But there were many poets quite like her well represented in this store, many with six or seven copies of their books. As I squatted low to scan the books on the shelves, I wondered who might ever buy these books, and I wondered if any libraries actually carried them. I wondered, as an archivist or librarian might wonder, if anyone was trying to document the world of very bad poetry, and if they were I wondered if they knew of this bookstore, which even carried a few high school literary magazines and copies of those anthologies people pay to see a poem or two of theirs between its covers. The experience was depressing.

What I wondered was how I knew these books were bad. Even books from the early part of the twentieth century. How did I know? And how did I know this immediately? Sometimes, I knew this from the typography. Pages and pages of floral typefaces tells one something. Tells one that poetry is a pretty thing about flowers and such. Sometimes, I knew this because I scanned these poems to see they were doggerel or bits of verse about "Life" and "Love" (the quotation marks and capitalization here being essential to an understanding of my meaning).

Finally, what I wondered most was why poetry was so bad, why so much poetry was so lacking in value, why poetry was so often written to fulfill a need in the poet without ever fulfilling a need (for knowledge, for awe, for entertainment) in anyone else. Why did poetry attract those who cared not for craft but only for the effort. And I had to wonder about my own poetry, a poetry of excess, a poetry based on speed of creation and delivery, one that varies wildly, but only to entertain myself.

I wondered why we poets were so without value.

Yet I found four books to buy, and I am glad I had found them: Karl Shapiro's Essay on Rime, a booklength essay in verse, with a bookplate of Ruth J. Geiger's exclaiming "The Poetry of Earth Is / Never Dead"; No Island by Spencer Selby, a poet visual and otherwise; Brian Kim Stefans' Free Space Comix, a book I never expected a copy of to exist in Utah; and a small chapbook by Gil Ott entitled "Traffic," the only one of these I've already read, and a great little book.

Why, I wondered (still wondering), were these here? and how did I find them?

I scanned the thousands of spines of all these books quickly. And I don't even know how I do this, but this is a skill honed from decades of searching bookstores. (So far as I know, I might be terrible at doing this, and I might even be passing over books I desperately need.) Somehow, I found these few books, and I think I can do this well because I've seen millions of books, because I have associations about different kinds of books, associations that allow me to find what I'm looking for quickly. While scanning the humor section at Weller's books, I realized I was looking for red spines of a certain height, that I was looking for copies of different printings of a specific book I'm quite familiar with.

In the end, I took much more than an hour to search every corner of this bookstore, yet I considered myself lucky to have found the four books I bought.

The Underpass on South 200 West Street, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)

The Underpass on South 200 West Street, Salt Lake City, Utah (14 May 2012)I took so long that I had to postpone dinner. I walked back to the hotel, watched a television show, then I returned to the streets, fairly bare this late at night and I ate a dinner of nothing but vegetables and beer.

Alone, I thought about poetry and how it works, and how it fails. I thought about the ways in which poetry works through associations (what we call allusions) and about how it works by undermining expectations. I wondered if it could ever be worth it to be a poet, if a poet could ever make works strange and yet somehow familiar enough to make a difference, to make a reader suddenly see something new, and merely by reading a words that have passed lifetimes under many people's eyes.

And I wondered about individual poets' chances of writing one good poem, or two. I wondered if the poetry I like is as bad as the poetry I hate, and that the difference between the two is merely that I've grown accustom to one over another. I thought about the randomness of my poetry, about how it functions as this essay functions, about how I pull as many disparate strings of thought together until I think I have something.

And I thought about how some poetry work assiduously to make great poems, even if they never succeed. And I thought a few thoughts about myself:

I try. And then I lose in trying. So I try again.

I live within an implicit dream. Even if it is a life, it seems (to me) to imply I am dreaming.

It must be time for sleep.

_____

* Why is "Greensleeves" one uninterrupted word?

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 16, 2012 20:48

May 13, 2012

Bibliomancy in the USA

Great Salt Lake from an Airplane Porthole (13 May 2012)

Great Salt Lake from an Airplane Porthole (13 May 2012)Salt Lake Plaza Hotel, Room 1107, Salt Lake City, Utah

As I traveled from Albany to Salt Lake City today, I read Russell Shorto's book Descartes' Bones. Subtitled A Skeletal History of the Conflict between Faith and Reason, this book presents us with an array of information all at once: a history of reason and modern thought, with a focus on Cartesianism; a biography of René Descartes and a chronology of what may or may not have happened with his human bones over the course of three and half centuries; a discussion of the mind-body/rationalism-spirituality duality; and a half-hearted call for an embracing of this duality rather than separation into warring camps of those the rational and the religious.

In its way, Shorto's is an ambitious book, well enough written, and only occasionally marred by disconcertingly anachronistic comparisons or half-argued points. Strangely, in Shorto's nearly journalistic way, he has written a book of ideas, a book on the history of knowledge and thinking, and a book that ends with a rather weak point. This entire book, about 250 pages long, unrolls for us a fairly complicated story about the Renaissance, the French revolution, the history of science, and (of course) Descartes, and Shorto decides that he needs a point, that he needs to be an intellectual himself, so he throws one it.

But I'll let that point wait for a while.

In the interim, I'll tell you about traveling, about how I travel, about the coincidences of life.

I'm tired of traveling. I've done it my entire life. At times, if there is less traveling and more touring, more engagement with a new place, travel is enjoyable. But more of my travel these days is for work, even if not for my day job, so I travel to a city, usually arrive at night, eat dinner, sleep, talk for an entire day, end in the early evening, eat dinner, sleep, and leave early the next morning in order to travel across time zones back to the latest time zone on the continent. There is little joy to such travel.

The joy I do make is sporadic. I document my movements. There is something about moving into new environments that loosens my perception out of its usual tunnel vision. I see places I don't usually see and I take pictures of items of interest to me. When I eat, I usually try to each food from the region I'm visiting. And I pull a single sheet out of the Gideon Bible that is in almost every hotel room I stay in, the sheet carrying that page with the number of the room I'm staying in, and I document where I was and where, in pencil, on the opposite side of the sheet.

Temple Square Seen from the Eleventh Floor of the Salt Lake Plaza Hotel (13 May 2012)

Temple Square Seen from the Eleventh Floor of the Salt Lake Plaza Hotel (13 May 2012)These sheets, probably about 100 of them so far, I save, I accumulate, and I maintain in folders carrying the title The Hotel Bible of America. This is my little conceptual art project. I imagine these sheets, not quite a complete Bible, bound together at some point near the end of my life, or afterwards, making it a document of my travels and my mild vandalism of these books.

By why else do I do this? Because the Gideon Bible carries with it two mythologies, the mythology of the book itself and the mythology of its effect on the world. The Gideons tell stories, possibly apocryphal, but also possibly sometimes true, about people who find themselves in foreign cities, aimless and lost, and who pull open a drawer of a desk, of a nightstand, of a coffee table, and who find a Gideon Bible, open it at random, and are overwhelmed and deeply changed by the words they find there, words that speak directly to them, that address their deepest fears, that instantly improve their lives. So I do this, also and importantly so, because I don't believe in these mythologies.

Honestly, I believe in the possibility that people might, through the process of self-convincing, come to believe that a book is opened to a specific page and that their eyes or finger falls upon a particular passage because of the intercession of God on their behalf. I can't believe in any god, so I can't believe as these people would, but I can understand their belief.

But every time I think of one of those Gideon stories, I think of bibliomancy, and that is the other reason for this project: to undermine the concept of bibliomancy. This particular form of divination usually consists of flipping to a page in the Bible and pointing to a page with one's eyes closed. The page so chosen tells you about your life or points you in a new direction, or so is the point of bibliomancy, if not the fact.

My form of bibliomancy is to choose an entire page in the Bible, one associated with my room number, so what words do I find on this page? what words from Romans, Chapter 8?

27 Now He who searches the hearts knows what the mind of the Spirit is, because He makes intercession for the saints according to the will of God.

What do we learn from this passage? First, the the Bible is almost unremittingly and stultifyingly boring. Except for Song of Solomon, Psalms, The Gospel According to John (well, the opening), and a sprinkling of letters in the New Testament, the Bible is unreadable. I often wonder if these few books are the only ones that courses on the Bible as literature can teach. The Old Testament is so filled with genealogical and other dry detail that a fingerpoint into those pages might land one with nothing more than a mouthful of begats upon which to base a new life.

The other thing we learn is that the Bible, especially when reading only isolated verses, is, at best cryptic. Apparently, the passage above tells us that people who search their hearts will understand the Holy Spirit, who works on behalf of the saints to manifest the will of God in people's lives. But I'm only guessing. It takes a great deal of imagination and faith to find something helpful in these words, though I am sure that people do. It's simply that I do not.

Third, we learn that the Bible as we have it, the one that we are likely to use now, is filled with seemingly random instances of italicization, that appear to direct us to pay attention to parts of the verses that do not seem particularly important or that are so obvious that any added emphasis on the words adds no meaning.

How does this help people? I could say here that I do not know, but the fact is that I do know, because I was once a person of faith. When you hold absolute beliefs that cannot be proven, you can find meaning more easily, because you yourself are the creator of all your belief. The pathways to that belief may be passed down to you, but you must create it in your own mind. I was once a Christian, a Roman Catholic, but a true believer. I believed in being good, in helping people, in transubstantiation, in a life after death, and in a benevolent God interested in my well-being. As a matter of fact, I am sure that I was the only person in my family who truly believed in these things, and because I honored that belief I could not retain the trappings of belief after that belief disappeared. I am now the only person in my family who does not attend Mass, does not celebrate the Eucharist, does not confess my sins to a priest so that I might be cleansed of those sins. I have other beliefs now.

The Hotel Bible of America is, then, a touchstone to me, that object (currently, that concept) that represents my loss of belief by tearing apart the Bible, page by page, to create another Bible, one seriously incomplete but no less meaningful to me.

I am not an atheist. Atheists are those who don't believe in God. I am a person for whom a belief in God is not a question, the presence of God is not in question. Just as I do not proclaim that I don't believe in giant worms that inhabit the moon, I don't proclaim a lack of belief in God. It is not a question needing to be asked, so no answer is necessary.

And that brings us to Shorto's point, to the entire point of Shorto's book, to wit:

One could argue that the antidote [to radical secularism] is to recognize the tendency to misapply reason and try to correct for it. But that ignores the second error, which is the greater. In the interest of pursing its own brand of certainty, radical secularism takes a too narrow construction of reality. It puts on blinders. Religion, like art, is a way of negotiating the complexity that the philosophical puzzle of dualism, and all of the attempts at overcoming it, acknowledges. To deny religion outright exposes those who trumpet the use of reason to the charge of unreasonableness—of intolerance.

This is, simply, nonsense. Shorto divides the thinking world into three camps: the religious, the radical secularists, and the religious secularists (my terminology given for the third camp). He depends on that third for an answer to two questions: how to explain the fact that we have minds that are somehow part of and somehow separate from our brains, and how to deal with the conflict between faith and reason. He sees these are related issues, which I believe is reasonable enough.

But I don't see a problem here to resolve.

We all understand, even if we cannot fully explain it, that the mind is the brain, that when we think that thinking occurs in the brain, in amazingly complex ways. We know that the brain works as a muscle, learning new tricks so that it can, at some point, make a great leap of the imagination and produce a thought, or an acrobatic move, or a work of art that had been unthinkable until that point. We cannot explain thinking completely, though we can do it quite well these days, but we know it occurs within the body, as part of the body. There is no real duality here. That is how bodies works, and not just human bodies, but even the bodies of the mud swallows I saw today flying in and out of their nests on the Utah State Capitol. We are bodies and we are minds all at once, simultaneously, continuously. It is merely that we think, sometimes, that they should be separate.

Now to the radical secularism that Shorto describes, and, more importantly, to its antidote.

I am not a religious person, meaning that I have no religious beliefs. It is possible, you see, though Westerners don't frequently consider this, to be an atheist, yet still be religious. But I am not. I am a stark realist, what Shorto might think of as a radical secularist, because I reject all religion, and I do so absolutely. But that doesn't mean that I think rationalism always works. There are limits to the human mind at different points in history, and there is much we do not know or cannot understand, things that we cannot even begin to realize we need to comprehend. Just because someone is a rationalist doesn't mean that that person cannot understand that mystery surrounds us, that we live in a concrete world, the workings of which are often inscrutable, possibly unknowable.

And I perceive, I feel, a kind of simple but deep pleasure in these mysteries. They are humbling. They explain nothing to us, but in doing so they lead us to realize just how much we need to learn, just how frequently our assumptions, even those based on careful observation or experimentation, are wrong. And they are wrong because we have allowed ourselves to trick ourselves into beliefs we cannot prove. That happens with the rational just as often as it does with the religious, and the two are not necessarily always separate. They exist within the same person.

But there is no absolute need for religion, and if there were would not we imagine that there was a need for a religion that was true? If so, what religion does Shorto suggest? Shorto has no argument. No, that's not right. He has an argument, but it is twisted by his own desires for meaning, for a inexplicable explanation that he can hold onto. What he doesn't have is an answer.

And I don't think the answer is more religion. In the last century we have seen the evils of many religions: Christianity, Nazism, Islam, Communism, Judaism, Corporatism, even Rationalism. These all drive people to absolutes, though certainly not in all instances, and absolutes are what allow people to carry out atrocities.

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

A true rationalist knows when an idea has been sufficiently proved to believe it, but also knows that additional information may force a change in that idea. The rational is about the possibility of changing a belief. When the putatively rational abandons the concept that belief may change, then it becomes a religion. And religion is what I don't believe in.

Honestly, I am a stubborn person, one who can suffer through much physical and emotional pain for my belief, or to do what I think is right. To remain true to my belief. But I am, also, someone who has changed his belief over time, and who continues to. We live in a world where all politicians pray to God (and manna), and where their second religion is their Party. Our problem, our society's problem, is not a lack of religion. It is instead a two-pronged problem: the proliferation of religion and the hardening of religious thought, the religion of God, the religion of politics, the religion of money. We now have too many absolute religious beliefs to protect, and we cannot protect them all, so we cannot accomplish anything.

I am sitting in a hotel room in Salt Lake City, the capital of an intensely religious state, and the view out my window is one of a subdued Las Vegas. There are bright lights, even a hotel limned in red lights, but the extravagance is diminished some. I can feel prosperity in the streets, something I don't really ever see in any part of New York. I could wonder, and I do, whether the political religion of New York (one that is completely bipartisan) diminishes the state, whether the state's embrace of abundant government and multiple levels of it (village, town, county, state; school district, BOCES, state; and it goes on) makes it impossible for us to prosper. Because we cannot change the seventeenth-century models we started with or dispense with the layers of government we've added over time. I am not a conservative. I am a flaming liberal, someone who believes in government. But I'm a rationalist, and I don't believe that government is an absolute value. I believe in few absolutes.

Assembly Hall from Behind the Walls (13 May 2012)

Assembly Hall from Behind the Walls (13 May 2012)So I am not a religious person, but I'm staying today in a hotel across the street from Temple Square, which is a city block of Salt Lake City surrounded by fifteen-foot-high walls. Behind those walls lie the Salt Lake Temple (only for LDS members), an annex to the temple, the Mormon Tabernacle, Assembly Hall, and two visitors' centers. I had been on those grounds once before, with my family in the early 1970s, and when I returned there today I found plenty that I had recalled: the acoustics of the tabernacle, the circular ramp inside the North Visitors' Center, the cheesy religious art, and the Stepford feel of the people there to aid us visitors and potential converts.

That Stepford comment hurts me, because I have Mormon friends, and they are as real as, sometimes even more real than, anyone else I know. I mean this comment only for the helpful aids. They seem to me to be kind people genuinely interested in helping people. I should explain that I am not a liberal who lives a life separated from conservatives. I have conservative friends. We don't agree on much politically, but we are still friends. One did leave me, I admit, without telling me, for reasons that had nothing to do with politics, but which had to do with his estimation of my goodness, but he also left another friend of ours over political differences. That dehumanizes us. Wanting, or worse needing, others to believe as we do removes the possibility of dialog, or friendship. That is a world I don't want to slip more deeply into, one I don't want our country or planet to sink into even more either.

I know something about Mormonism, maybe more than most "gentiles," because I have Mormon friends, because I'm interested in people's religious beliefs, and because I'm related to the prophet Joseph Smith himself. Today, while touring the visitors' centers, I was reminded of all the beliefs in Mormonism that I find, honestly, silly: the visitation by Moroni, the incredible story of the golden plates and the special glasses for reading them (and the loss of both), the scrap of paper onto which Smith copied some of the strange symbols found on the plates, the story of Jesus' coming to the North American continent, and the story of these many peoples and their civilization that thrived on this continent without leaving behind any archeological record.

Yet I don't ridicule the Latter-Day Saints for believing these myths. The Judeo-Christian myths, which the Mormons also believe, are just as ridiculous, just as those of Hinduism are, or even the classical myths no-one believes in any longer. Religious is a human endeavor concerning the holding of impossible beliefs. And if people need to believe in such things, that is their right. We have a right to all of our beliefs, the stupid and the real. We have a right to be wrong, and we all are in some way. Because religious believes are personal to people, I give them respect, though never belief. I'm more likely to make fun of people for believing in ghosts (which belief exists in epic proportions today) than to do the same to people who hold religious beliefs.

I walked behind the walls of Temple Square this afternoon, and I thought about these things. I was respectful and contemplative. I wondered, even, if the religious art and dioramas in those places actually soothed people. I wondered how believers saw these same objects I did. I wondered if the typographic excesses of the displays drew them in even as they repelled me. And I thought of the honor of their belief. There I was in the center of a religion, in the mecca of Mormonism, and I thought of the belief so many of them had, of the fact that so many of the original pilgrims to this place were so impoverished that they traveled thousands of miles pulling handcarts. They were their own beasts of burden. I thought of the prejudice they suffered for believing differently than their neighbors and how they still held onto their beliefs. I don't question their belief, even if I cannot personally understand having it.

But belief doesn't hold anyone. The young shuttle van driver whose name is the same as my paternal grandfather's and who brought me to this hotel today told me that he was originally a Mormon, but that "It didn't take." I said, "It happens." As our conversation continued, he ended up saying, "I don't believe in any organized religion that includes people." And I suppose I can agree with him. Maybe the concept of religion is comforting, but religion might not be good for people.

Still, we should have a right to do things to and for ourselves that our bad for us, if that is what we want. Anyway, it's more interesting to have a world filled with a confusion of believes.

Inside the Utah State Capitol (13 May 2012)

Inside the Utah State Capitol (13 May 2012)A couple of hours after my tour of Temple Square (the fifth most visited tourist destination in the country, I am told), I walked up the hill to the Utah State Capitol. Although it resembles most state capitols (the dome is the giveaway), it is situated strangely up the hill away from the center of town. It is isolated up there atop the hill, with a fine view of the mountains enclosing Salt Lake City, as if the world of government, the world of this life, would somehow be inappropriate if left beside Temple Square. Or there's another way to look at it: the Capitol sits at the highest point of the city, and it overlooks the city as a mother stays high enough to see her entire brood.

As I entered the capitol, I realized that it was actually a cathedral to government, as all capitols are. It was ornate, imposing, and a waste of space. It was designed to fill us with awe, and indeed it did. The capitol was merely a cathedral for another religion: the religion of government, certainly, but also one tinged by Mormonism. Here, in this cathedral, the rational (in the form of government) and the religious (in the form of religion) came together, to form that third state that Russell Shorto imagined as the best for mankind. A state of grace in which the rational and the religious, where reason and faith, held sway within the moment of a single thought.

I am still unconvinced that is a good thing. But I realize it is a common one, and maybe one better than belief based solely on faith

A House on a Hill on Main Street, Salt Lake City (13 May 2012)

A House on a Hill on Main Street, Salt Lake City (13 May 2012)As I walked up the hill to the capitol, I passed a number of homes that were overflowing with beautifully tended gardens, gardens of plenty that washed over these small plots of land, leaving little space for lawn. These reminded me of my hometown in Millbrae, much of which is quite hilly, and which was the center of my life for many years, even though I lived there only until I was a few years old. I was baptized in St Dunstan's Church in that small city. My great-uncle was a jolly man who ran a school for the deaf and who was a model of service and good humor that all clergy should follow. My family was religious in the sense that religious observation was important, so we attended Mass every Sunday, and on every holy day of obligation. I remember, when I was still very young, seeing the priest say Mass with his back to us.

I call myself a secular Catholic, because I cannot wash my history out of me, but my rejection of religion has made me somehow separate from the rest of my family. That is one reason for belief: to fit it, to belong. But I cannot worry about that.

I can't because I am a poet. Belief doesn't guide me, even if vision (and hearing) do. Often, my poetry doesn't even add sense to the world; it adds chaos. And chaos is perceived by the human mind as a form of mystery. The human mind is determined to find patterns and organization, even where they do not exist, so chaos disrupts that need. Chaos is find in poetry, though, which is meant to be about surprise, and surprise might be about a mystery revealed, or a mystery interred, a mystery kept behind a curtain, so that we can merely imagine its shape from the sounds it makes.

If I think about my life in poetry in religious terms, I believe that I am dedicated to poetry in almost the same way people experience religious fervor. It is brought on by myself, but it is real. Still, I am not a believer even in poetry. I don't believe poetry can save us, even if it can enrich us. Even though I believe in the mystery of poetry, I also understand its mechanics (of soundshapesense) well enough to understand how it works, and how to break it. And I don't believe in any particular kind of poetry.

I may be a promoter of certain kinds of poetry (say, visual), but I don't believe that the poetry I promote, or even the poetry I make, is the one true way. I don't believe in true ways. I believe in possibility.

So, even when it comes to poetry, I am not a partisan. I need no religion in my poetry. Because religion barely moves.

When the truth is absolute, there's no need to change it.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 13, 2012 20:46

May 9, 2012

If it Had Not Been Stolen, It Would Not Be Worth Keeping

An Untitled Visual Poem in Four Parts by Scott Helmes and Anne Gorrick (2011)

An Untitled Visual Poem in Four Parts by Scott Helmes and Anne Gorrick (2011)I have found myself.

No, not quite, but the beginning is right.

I have found myself, I have come to discover myself, in the process of writing a book I did not realize I was writing. All of the poems are long, at least five or six pages in length, and usually many many more than that. All of the poems are built upon found bits of poetry that I appropriate, arrange, and then expand upon.

It is a musical kind of writing, even if the music is silent. It is a riffing off of lines, a sequence of worded notes. And then another.

(I'm writing this having just fallen into sleep with a computer in my lap and my fingers on the keyboard. Some of the words I found left were English, but in the wrong key, my falling mind failing to write the right word down, hearing something else instead and putting that in its place.)

It is a poetry of stealing and of having been stolen from. It is all I can do to keep from writing one of these poems. I am a kleptomaniac in the storehouse of words.

It is a poetry of the impersonal made personal, a poetry of one person found inside the shape of another. I am not a shapeshifter, but I fill the spaces that the shapeshifter has moved through.

I have taken up with words and am too taken by them to leave them. They gather around me like moss. If I shake them off, a thin mist descends upon me in a cool corner of language and I am soon covered once again.

It is not that I am a writer but that I am a being who is written through. Conduit, not construct. Acequia madre, no agua.

I work in fragments and build fragments around those. I am a mosaicist, not a sculptor. I do not take away from. I add to. Caribbean coral, not hurricane winds.

In this way, the process of addition is a process of subtraction, the initial words, the germs of the poems, being reduced, being diluted, to ever-smaller quantities until they almost disappear within a new stream of words.

The line of thought is not a line but a sequence of ever-diverging furcas. It is a fractal poetry, endlessly repeating itself outwardly and inwardly.

In one case, the last (meaning in the object and completed fact of the last poem I have written so far, not meaning in the fact of my having completed the final poem of the sequence) I did not choose fragments to work from. I chose a fragmentary and prismatic poem by Anne Gorrick, a poem that is a set of four sets of words, each assigned as the textual matter of a sequence of visual poems she created with Scott Helmes. They are beautiful as words and beautiful as parts of colorful visual wholes.

In that case, in the case of Anne's words, I stole them whole, I stole them wholesale, without discretion.

In this case, I have built up around the stolen words. I have added words around them, between them. I made one version in this way, and then I took that version and I made a version from that in the same way. I subtracted no words. Occasionally, I changed words, but only those I myself had written, replacing each word with a word I thought more appropriate, but never editing out a word and leaving a lacuna in its place. Addition alone, never subtraction, guided my practice.

Through five sets of additions, I expanded the poem into something much longer than I imagined it would be, and it now fits within a book I am writing, a book that seems subsiding into completion.

As a last thought, I'll note that these poems are not really written to the people I have stolen words from, and they do not represent an honoring of their words. Mine is an act of poetic defilement. The originals may shine through, but they are covered in the mulch of strange and extraneous words. What I write are my own poems within the corpses of others' poems, and those are corpses of poems I have personally killed.

These poems are poems of defilement and thievery and of twisting the meanings of the originals into the interests of my own mind. If they were homages, they would represent something else, they would be kind to the poets, they would continue the poets' ideas, their voices.

Certainly, I mimic these poets through this process, but it is only in order to steal their souls, to change these souls into something else, and to sell them to the devil.

The clink of coins arises from my pockets as I walk.

Four Visual Poetic Rectangles

—expanded from lines by Anne Gorrick

1

in the upper left

that alizarin, crimsonmadder than her low-red voice empurpled then drained

regret defines variancethe tiny articles of beingthat extract the succorfrom the suckingthe sucrose makes itsweeter

all flavours of colour

it is all splendida violet the colour of flowersand so sensitive it’s almost

a petalfloating

a river of movinga thought expressed from the body and extendedinto whatever is

transitory, a radio, a rosary the way we sing out of itthe way it sings us out of itself

my voice is wordlessmy voice is worldlessmy voice is worthless

the breaking that singing causes in usthe sense that we had been brokeneven before we have sung

a single worda married thought

how crimson leansdeep deep into usalmost to the point where we are

green but deeperthan that darkness

deeper than deaththe depth of it

almost lost

to it

2

towards the upper right

a royal appropriatefor colours as flags are

the waving silkskin the colour of milk

the silkskin cockthe silkskin cunt slippery for inningfor giving

these tonalities of the ear nor eyerequiring the tongueto slip in to lingerover

the long it takesthe longer it takes

the more it comesthe more it leaves

the budding leafing treesof tenderest meanscatchers of a soft sunlight

the falling elmswelltan and moving as sand

what forms upon an additional ground, a paste of dust, the magenta of it

or pearls’ scent

she cannot see through the sea taste

of me

these areclouds plastered downin immovable colour

in quinacridone,I am painted into placeupon her within herunchangeablein escapable emotion

movement encased in stasis

in constant emergency

we are also painted theretogether

see the red 5so vibrant on our bellies

see the pearly 5so languid on her belly

what may be a snakeits slither away

still a slither toward

somewhere

3

from the lower left

a beautiful gloss to it, like glass

vitreous light

nystagmus caught mecaught my sight of it and

I thought, gliss,but could not hear it

even from a listen

I would glessthe meaning of it

into some raw unthought thought

the gluss would eat allI threw up to it

the gluss would eat all

facts like sprays of violets in a reddish purple

the colour of bruisingnot bruise

or a 19thcentury fury all in the eyes

a small creaturecovered in furwith tiny beady eyes

or a small creature nearly furlessbut mammalian andhow her seeming nakedness was

to me

although it wasn’t it wasn’t permanent

never is

a(lilact) tonal

in the eyes I fracture in the heartI come apart inside her Irupture

4

forward into lower right

into the red like rosinshe leans into shadeof the Japanese maple

like a distant violet antand violent too

there is a shade in herin the crevice of her so deepthat it is a pink that’s almost redand there I go

again

even with our eyes closed

overseas, things are almost noirâtre our aster succumbed to darkness

the eyes closed enoughto allow the feeling of it

as the deep blue covers

it all up

(the eyes close enough)

it covers the weak and the dying

the me and the she

I could not speak to her as youI could not say if she were true

color is an abstraction perfectly palpablethose parts of her that are palmableI move her with the cup of my hand

with that alizarin, crimson,the scent of cinnamongrowing

she is a scentlike cinnamon but not cinnamonand growing

and reaching

out

to me

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 09, 2012 20:00

May 4, 2012

The Hill Gate of Freedom Horn (A First Erudition)

I am in a battle of wits with myself, and I keep winning. So this means, also, that I keep losing.

Last week, not the week just ended but the one before it, I was traveling, to Austin and back, all as part of my other life, a life as an archivist, specifically one who talks, who cajoles, who calls people to do. I am a speaker, a man of words, so I fly places to make those words for an hour here, a day there, and leave. It is a tiring life, and I've made many trips already this year.

I read while on planes or in airports, and I ended up reading five books, four of them while traveling. During all of this, I thought of myself as a sponge, but not of cellulose, not one that soaks up water, that fills with knowledge. I thought of myself, I always think of myself, as a living sponge: stationary, and the water moves through me. I don't soak up knowledge. Instead, knowledge flows through me.

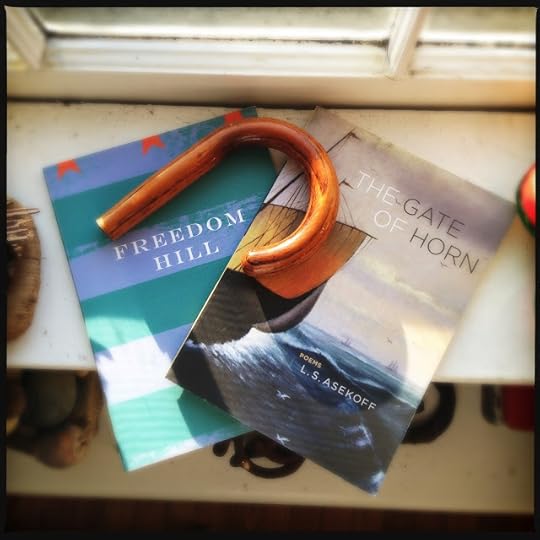

This is a story of how knowledge flowed through me during a couple of weeks of my life, and of what that flowing made. It is also the story of three books, two of the by L.S. Asekoff and one of them by Gaius Aurelius Catullus, the story of how those books, how the poems within them hit me and how I responded to the pummeling.

It has, yes, occurred to me that my reviews of books are more responses to them, and thus unfair to the books and the authors of same. So I will publicly apologize here to Louis Asekoff for not creating a proper review of his two books of poetry. In memory of these poems let's take a few seconds to hear Louis read his poems (with my friend Anne Gorrick introducing him).

For, you see, I have met Louis, even heard him read, in Kingtson, New York, on February 11th of this year, a day of some kind of loneliness and the anniversary of the death of Sylvia Plath (some facts adhere to the contours of the brain). Louis' reading was quiet and steady, filled with words, which I think is good. (Such a reading is the opposite of a reading that is loud and pianoforte, filled with sounds, which is the way I do, and which may be another kind of good.) I bought two of Louis' books from him at the reading, The Gate of Horn and Fredoom Hill, and I was particularly interested in reading the second of these, which is a booklength monolog spoken to an apparent but unidentified (and rarely referred to) other.

Wanting to read Freedom Hill first, I read The Gate of Horn first, so I could read them in chronological order. I read these books mostly while in flight. In The Gate of Horn, I found poems in various shapes, on various topics, but which were stitched together by their ravenous erudition. With lines long and languid, these poems stretched out across the page and out across my mind. One poem opens with the speaker explaining that he (we assume) is a bit off, having just awoken from a dream of words, and that's what these poems are. One after another they unfurled themselves in these long long lines, many reaching more than half-way across the page. These poems had a touch of Ashbery to them, a bit of awkward but benevolent beauty, a reaching across forms of speech, a tendency to accumulate images, words, phrases, epochs. Yet there was something more stable in Louis' poem, something planted, if not altogether firmly, at least somewhat, in a certain point of view. And through all their corsucating vocabulary and imagery, they had a sometimes palpable humanity to them, meaning a sense of a person sitting on the page being a person. As I read, I underlined phrases here and there, found pieces to steal. And I hardly noticed the strange description of the work life of an archivist, or even the reference to serifs in handwriting.

Freedom Hill was something else by something similar. It's lines were even longer, suggesting prose instead of poetry, but their length suggested not a languid reading, but the fast speaking of a hyper-intelligent academic speaking to his acolyte. (Of course, at his reading in Kingston, Louis essentially described this book as a reworking of all the stories a former professor had told him over the years. Listen, and you will see.) The story of this poem is of a literary man, highly educated, talking about his life and loves and losses, and complaining as he does. The character is well formed and changes over time, sometimes dramatically section by section, and he talks and talks and talks, allowing the lowly auditor, the transcriber of the speech, the one who makes the speech possible, to disappear under the words. Even in the face of a seeming one-way stream of words, what we really see and feel are the interruptions, how the speaker who allows himself never to be interrupted still undermines his own speech, every few beats, to move in another direction, how this one-man conversation takes on the peripatetic characteristics of a conversation. It is a remarkable thing to see.

With Asekoff in my blood, I began to consider the poem I would make with a few of his stolen words, but work was busy and I didn't start the poem for a few days.

In the meantime, I found Catullus. Drawn as I am to Catullus' Carmen 101, I thought I'd enjoy reading of book of his poems. I had no idea. Catullus was simply a direct and ferocious lyric poet. Moving from invective to supplication, from ardor to despair, he exhibited the entire range of human emotion and being. His spleen was as big as his heart. I pulled even more lines out of Catullus, because at this point I figured out what kind of poem I would be writing. Over the course of three or four days, I scraped together a poem (27 pages in length) that steals from Catullus (the translated English and the original Latin, steals from Asekoff, and fills itself with Huth, as it talks about the self as poetry, poetry as lover, and rails against, cries of, decries the fact of poetry.

This seemed the right poem for this moment in my life. It is a poem seemingly randomized and specifically structured. It changes its mood tiny section by tiny section. And it bravely hopes for a reader hardy enough to read to the end. The references in this are many, and includes ones no-one will understand.

But that's the most we can hope for poetry, so all will be fine.

69 Cattails

Carmen 1

Times are bad enough without you lousy poets to make it worse

The wordsand only wordsoh the worst of themyou use

as ifour brains could care to hear you

through

to that plinking end

of every soundof your tinny voices

Wouldyou were already buriedwith catfish and carrots rammed up your holes

something (for once)valuablecoming out of your body

Carmen 2

There is no differentword for

Poem versus Song

“The Ultimate Battle”

Carmina 3

O maiden so modest

O virgin so pure

I am full, flat on my backand my cock’sblasting up and out through my underwear for you

my poetrymy poem

Carmen 4

Up your ass and in your mouthyou stupid, furious, cocksucker poets

What words would you have me use?

asphodel?countrymen?Norfolk?

You are neither man nor beastnor woman eitherbut some calcified bit of poisoned earth

Call me dirt,but remember

that is the soil where life grows

Nothing lives in your polluted dustI walk over when heading nowhere

My poems are filled with the fuckingwords of fucking and life

and they’re as gladas I amthat you rotting corpsessee not the life in them

Carmen 5

Women bleed involuntarily under the moon, and under the sunthey bleed as well

Take this small napkin,fold its cloth into a triangle,and hold it against you whereyou come together inthe scissors of your legs

A wound might weepbut not this sweet centerof youwith the slip for potteryin my hands as a vessel

I take across any sea

Carmen 6

Once that brief light goes out on usthe night is but one long sleep forever

cumnobis semel occidit breuis luxnox est perpetua una dormienda

Once that brief light goes the night is but one long sleepforever

cumnobis semel occidit breuis luxbreuis luxnox est perpetua una dormienda

nox est perpetuanox est perpetua

Carmen 7

a poetis a cheap whore who hustles every holein his bodyevery holein her body

just to feel

just tofeel

justto feel

all these ravenousears uponhim

or her

hymn or hurt

or me

Carmen 8

Though I am worn out with constant pain and sorrow, and no fit company

though I am wornas a small badgeand rememberedin my absence

though I am warm,still, and not quitedead, and rememberedfor forgetting the words to my poems

though I am wearied by constant painand sorrow upon medaily and into the nightand I am not wortheven the company of my words

I take to the comfortof this hard desk(Dear Reader)to write such wordsas you will never read

and even less likelyneed

Carmen 9

non iam illud quaerecontra me ut diligat illa

non iam illud quaerenon iam illud quaere

Carmen 10

“Touch is like bread” “Touch is like breath”“Touch is like breast”

Touch is like beast

Carmen 11

[pershist…

Carmen 12

my every happiness perished to the last with you

perishedto the lastknuckleand bone

last fingerfingering

the lastwriting finger

writingthe lastword

Carmen 13

& acres & acres

surrounded

by acres& acres

of ashberries

floweringflowingerringairing

off

Carmen 14

Why wait, Huth? they ask

Go drop dead right now,they say

YetI rise

Carmen 15

gratias tibi maximas Huthusagit pessimus omnium poeta,tanto pessimus omnium poeta

Carmen 16

What I couldsee in that proleptic lightof tomorrowmorning

What Icould seein mourning

What smallpieces of lightbroken bymy fingers and heldin my palm

and keptso dimI need wordsto see them by

Carmen 17

ut te postremo donarem munere mortismortis mortis

et mutam nequiquam alloquerer cineremcinerem

cinerem

Carmen 18

the “lack” in “lilac”the “light” in “flight”the “loss” is “loss”

Carmen 19

The mouth is a wound

wound rounda word that

falls from a mouth

making a word from

the woundthat’s a mouth

Carmen 20

and if I wereto ease my mind of my own deep trouble and darkness

a darknessapproaching night

if I wereto slip my minddown into that darkness

soft and sweet and deep

I might leta poem ripfrom between my legsone so loudand lively

even lovely

that everyonewould stop to listento stare

whether theyloved the poemor poetry itself

yet I lovepoetrymyself

because it isso perfectlyworthless

it cannot changea thing’cept to make it worse

Carmen 21

deprecor illam assidue, uerum dispeream

nisi amo

Carmen 22

You pansy phallus,soft as rabbit’s fur

hard as goosedown,or a nibblesworth ofa sweet little earlobe

just an old man's limp dicktrapped by fraying cobwebs and malign neglect

how will you everhelp me writemy own stupid poems?

what inspiration are you, so soft

that flaccid makesyou hard

Carmen 23

nullberries

Carmen 24

Omy dearsweet poem

all ready for me

looking so isoscelesed and equilateraled

your puckered apricot & indigo

delta

all forme

Carmen 25

I might as well scribble in wind and swift water

Carmen 26

All we do is but

the pale image of what

we dream of doing

Every poemis just

the lostwill

to make a poem right

Carmen 27

We have been warned against nostalgia

nostalgia for a time when people had something to be nostalgic about

We have been warmedby nostalgia

too

There is something vaguewe remember vaguelyor we touchin a vacant or vagueway

We’re all nightingaled now

Carmen 28

My heart achesemptied

I leave the world unseen

and quite forget

the weariness

for I will fly

on viewless wings

of poesyhere

where there is

no light and I am

half in love

with easeful death

to cease upon

only midnight

opening on the foam

of perilous seas

Carmen 29

why no woman is willing to spread her legsfor your poems

is becauseevery she is alreadyyour poem

Cuntstruckyou babblebut neverfinish evenone of them

and only thatsaves poetry

Carmen 30

Maybe sometimesome of you will read these words,clumsy as they, and still not mindto lay your hands,to rest your eyesupon them

to lay your softhands tenderly upon,to rest your steadydelicate gaze upon,to releaseyour whispered breath

upon

and then overand then throughand finally beyond

me

Carmen 31

I’m smart enough to see the limits of my brilliance

My bald patecould never lighta ship’s dark passage

So I sailblindly, valiantthrough the dark

Carmen 32

hurt a Huth in love and helusts for youmore, but the less he really cares

huth a hurtand it humsmore for youthan him

if hurt did notexistwe would

neitherwould we

Carmen 33

Momentum ofemptiness

filling emptiness

with momentumof forms

filling immenseforms

with all thisemptiness

Only the blankallows for

the filling-in

Carmen 34

I crossed many to get to this so I could give to silent asheshere with me,to tear us apart,bring these offeringsafter the customsoaked with tearsand forever more.

Carmen 35

Many people and many oceans I have crossedto arrive, my love, here at this grim burialthat I might give this last gift to you for death,to waste a few words for these empty cinders, since earth itself has taken from me your fleshand you are lost wrongly from me again, and ever,still I offer these small words to you in keepingwith the signs and stones we leave upon burialscovered all with a lover’s tears for you to takeas things given in perpetuum, endless farewell.

Carmen 36

Many people I crossed,

at these poor burials,

[to] give you the last

talk (with mute ash),

tore you from me, you

taken from me,

now still anyway this

handed-down gift

soaked with tears

and into forever.

Carmen 37

so muchgets lost in transliteration

that I justtranslate it allinto languages

I’ve neverknown

Carmen 38

Let poetryenjoy herself with cheap lovers

Let herclamp them up between her legs by the hundredsby the hundreds and hundreds

And let her say it’s lovethe only love she’s ever feltwhile one after another she breaks them inside her

she breaksthem inside of her

one by one

Carmen 39

I throw the words

out

to the world

Pigeonswon’t

eatthem

Even pigeonsrefuse

to eatthem

Carmen 40

nulla potest mulier tantum no-one can say that she herselfse dicere amatamso much was lovedquantum a me amataas much as I loved

as muchas I loved this poemas I loved herthis poetry as muchas I loved these wordsas muchas this need for poetryI loved as muchas these words I spokethese words I wrotethese useless wordsI have not yet foundthe time to lose

the time to forget

time toneglect

time to leaveto turn toruins

Carmen 41

don’t tear me away from what I care for even more than my life

yes, even more than my putrid life

don’t tear me

don’t tear meaway from theseformless words

from thesefordless turds

from theseforgeless turnsof phrase

(Take a breath)

Carmen 42

It doesn’t matterwith a poet if you kissthe person’s lips or the ring of the asshole

each as sweet as the otherand from each there slipsthe same sweet poetryheavy with scent

but the cornhole’s got to be better

it has no teethno rotten gumssagging longer thantheir sesquipedalian words

Just avoid that rotten smilespread open and dripping pisslike a mule’s cuntthe body’s own honeypot

and just as uselessas a word

or even morethan one

Carmen 43

dulci dulcius ambrosiaa poet’s fart

Carmen 44

sentence by sentence

it opens up to me

word byword

in comesinto place

I feelthe shudder

the shutterwhen it does

Carmen 45

in uento et rapida scribere oportet aqua

Carmen 46

poetry like mass hysteriahas its advantages

like abandoned buildingsriding on chemical sludge

like a rotted treetumbling ontocrashing through your house

like youlike me

Carmen 47

I am

where one’s cryfound its blue echo in a sky

I am

where one’s tread would runover his head

I am

where one’s viewrises fast only for you

Carmen 48

I curse herwith a vengeanceand I swear

I love her

(oh)

Carmen 49

et tristis animi leuare curas!

Carmen 50

out of which all contradictions flower

I come & come & come

again

Carmen 51

odi et amo

this fucking poem

these fucking words

even after all their fuckingthey cause no joy

they makeno babies

no sense

no one

Carmen 52

so I could finally give you gifts for the deadthe dead

and waste time talking to silent ashes

these ashesthat markmy forehead

(you know what they sayabout children bornon a Wednesday)

Carmen 53

wreck’d & toss’d

the tortillas soak up the mescalwhere the tequila should be

the drinking’s a drainingthe eating’s a coming

Carmen 54

His razor wit guillotined

cut the vein just right

cut the vainjust write

le jet d’eau

mais l’eauc’est le sang

sed in sanguine est aqua

a song so red

sing it steady

just a stream

but a fountain

the flowthe flow

liquid

and ink

Carmen 55

everything pellucid

the conjunction of two

whiter than winter

than wither

still life in white

it is still life

th’erection’s flow

the push and the pulse

the spasms of being

the white cum of self

everything pellucid

everything milky

everything salty

all of this life

Carmen 56

Quid est, Huthe? Quid moraris emori?

My weight is weighted, in favorof moving

you

Carmen 57

Come on, please little,please, my little sweet isthmusof a girl, you deliciouspiece, pleasebe a good girl and let me fold myself around youand slip myself intoyou, so slick and slendera slope inward, so sweet and wet

for you are only words

only the onlywordsI have

only the lonely words I have to call youto make you

to call youforth

Carmen 58

What rabid purpose guides this stupidity of yoursand throws you so clumsily into my poems?

What mindless phantom of your puny imaginationsets you up for such a fucking pointless battle?

Is it that you just want people to remember you?Is that what you want? To a find fervid & empty fame?

I see, you think taking my love, my poetry, will do it.Maybe I should make you suffer forever within my poems.

Carmen 59

What does it mean to lead this posthumous life?

What does is meanto slip into syllogismsthat never direct?

What doesit ever mean to find yourselflost?

Whatdoes it really meanto writea stupid clucking poemout into the headless empty

we live ever within?

Carmen 60

You know the drill

First, there is smoke & then bells ringinglike Sirens

Then a dank burnt& whispersthrough what used to be

& that little clickas your assholes close

(tight & tense)

& you know it is allcoming back

& harder this time

much much harderthis time

Carmen 61

I’m not asking that she love me back any longerfor I can no longer get any longer myself

I am asking that she rememberthe singing

the singing there used to be

Carmen 62

into this gorgeousrubble this poemeverything collapsesinto this gorgeousrubble this poem

I can livefor poetryno more

Carmen 63

Seethat it lasts for more than a lifetimeinside you

this poem

that it lastswithout youthat it leaves

itself behind

Carmen 64

But you won’t escapeyou’ll never escapemy poems

Carmen 65

I know the shapes thatmy memories of myself take

how these shapeschange and howthey take the forms of dreams

of beasts long thought dead

(if I were a native parakeetof this same centuryof this same countrywhere I live)

every dreamis an action towards remodeling the worldimage by image intoa contradiction of itself at a microscopicand infinitely continuinglevel

the act of memory beingin this instance the act of forgetting

Carmen 66

Pedicabo ego uos et irrumabo!pedicabo ego uos et irrumabo!

Carmen 67

nam pransus iaceo et satur supinus

pertundo tunicamque palliumque

Carmen 68

Yet who do not want reparations for their childhoods?

Yet

who does not want themyet?

Carmen 69

nouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututionesnouem continuas fututiones

thanking you, I remain, in closing (finally,I know),

truly yours, Huth, the lousiest poet of them all,certainly the lousiest poet of them all

______

Asekoff, L.S. Freedom Hill. TriQuarterly Books / Northwestern University Press: [Evanston, Ill.], 2011.

__________. The Gate of Horn. TriQuarterly Books / Northwestern University Press: Evanstone, Ill., 2010

Catullus, Gaius Aurelius. Selected Poems of Catullus. Translated by Clark Sesar. Mason & Lipscomb: New York, 1974.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 04, 2012 20:27

April 26, 2012

Clouds, Ice, Alphabets, Voices, Darkness, Rain, and Dark

I do not know how many times I have flown over the Atlantic, but the first time I did I looked out the porthole at the clouds floating below me in the sky, and I believe we were flying over the Arctic. Aged six at the time, I did not know that I would learn that those clouds were not ice, that the sky was not ocean, and I would learn it by the simple process of experience.

A dream dashed. We survive on the lies we tell ourselves, even if we are poisoned by the lies others tell us. Lies are merely things that do not exist, like ghosts. If ghosts sifted through the walls of our homes, we would be overcome with constant feel of waves of cold seeping through us, of the evanescence of death sweeping into us, deep through us. Yet we are lost, we are somehow damaged, by not having these fears to depend on. Or angels. Or gods. Or life everlasting. Amen.

A rain came an hour ago here in fat cold drops, yet I could not feel them to determine their cold. Yet I knew they were. They were drops of night, coming not black but white, just a little greyed out, for every drop fell through a stream of light, so every drop was filled with that light, and took on the undefined contours of it. When the night fell from the sky raining around me tonight, it fell in the form of lamplight, wet and cold and big, but bright.

I took in my hand today a pen only recently purchased and wrote, but I did not so much write as I drew, but I did not so much draw as I wrew. And what I made were poems, only two: one made of letters that never existed, except that today made them so, but which still carried forth a message, to the future, to the present, not quite to the past. Something there was that sustained that poem, something about the shape of the letters and how they fit together and how they seemed almost of a piece, how they seemed alphabetic. (I wrote about half of this poem while riding a bus, so it preserves evidence of the means of its creation.)

If you write a message in words that no-one can read, it is unlikely they will send a search party to find you. But it is likely they will live better with the words stuffed into their eyes.

A vain claim, I realize, but one I feel compelled to make, against any hope for belief, after reading a beautiful little essay about shamans in poetry by my friend Stephen Nelson wrote recently, an essay that includes a few words about one of my instances of singing.

When my friend Geof Huth performed a poemsong at the Text Festival in Bury exactly a year ago this weekend, I thought he was a shaman. He sang into the collective energy of the room and, somehow, altered it. How this works at an atomic or subatomic level is beyond me, but I do know how it affected my body, and, more than that, how his song reached beyond my body’s physicality to a more subtle level of being where I might have found myself interacting with the memories of the room and everyone in it. His song transformed the room, altered the mind of each individual, and by extension, the families and communities those individuals belonged to.

This adjustment, this ability to heal and transform makes every poet potentially a shaman, particularly I think sound and visual poets, whose work frequently steps outside meaning into areas of pure sign, pure sound. What matters most is the loving intention he or she brings to their marks and utterances, and how that communicated intention can alter the reader/hearer’s state of being.

All of which makes nonsense of poetry wars and poetic rivalries. When a poet sings, he sings for all the poets, for a whole community of poets; similarly, when one of us suffers, we all suffer, whether we’re aware of it or not.

I wish, of course, that I had the ability to heal, that my could heal, that my singing could, my touching, my marks made onto a page, a screen, a wall, even a small corner of a ragged rugged yard. And to believe so would be to believe a rich and sustaining lie. But I cannot do it.

When I sing, I do it to affect people, to burrow into the deepest part of people without ever touching them, but I expect no effect. I just wish it. And wishes are just wants, things we are lacking. Stephen, I believe, though, felt something as I stood up that night in Bury, up out of the dark of the theater, out of the audience and up onto my feet into a bubble of light. I'm not sure why. He is a better singer than I am, a better musician, and by miles. My voice is the sound of a saw against wood then hitting a stone the trees grown around enough to hide within the cylinder of its body. I sing almost tunelessly, not of music, but as if struggling through sound to a music I cannot find. Still, these sounds are sometimes powerful to me because expel them as if spraying human and bodily feelings into the air, fat cold things that seem like pieces of night falling but which catch the light just long enough and bright enough to light the faces of the listeners, if but for a second.

I have had a long two weeks traveling back and forth across the continent in small loud planes so that I could perform before people. And these performances were not poetics. They were pedagogical. And comical. For I cannot teach in person without telling jokes, sometimes so furiously that a conversation about digital preservation formats becomes a stand-up routine. I know it is hard to believe, but it is true. At one point two days ago, the audience was laughing so continuously that I knew I had to pull back from that humor (which is almost a drug for me) so that I could keep the audience focused enough so that they can learn. Humor is important in teaching because it is a core element in my simple theory of education: You must be awake to learn. But humor gone to far disperses the mind to finely and broadly, spreads it so thin that learning slips right through it, and falls, as if darkness falling through darkness, yet light by a light from within.

So when I read Stephen's essay to me, a message from a Scotsman to a fellow Scotsman, I was filled with the cold and heavy weight of his words, words made cold because I could not believe them, words made heavy because they gave me the burden of being something I could not be (a shaman, a healer, a mover of souls). But when these words fell on me, cold and wet and slapping sharply the skin on my face, they turned to light: brightness and weightlessness. And I was held aloft by my believing in them, by my allowing myself to feel them for just long enough to heal about from the tiredness I was discarding and from the weight of work I was pulling back onto my crooked back.

It is a gift to be remembered well, even if too well. Recognition is two things: The assertion of one's value and the knowing of who one is. And it was good to be known, and even to be asserted into something I could not fit or flee.

I write, I realize, as a poet. It is a disability I cannot recover from. It is a failing I cannot shake. So I stand still for a moment, or I sit still, and I write. As I am doing now, in the rainless dark.

After my bus ride, I did not return directly to the small place where I live. I went, instead, to a neighborhood institution, for a couple of pints and an easy meal, a hot chili to warm the soul, a fine salad to soothe the body. While I was there, I soon realized I was in the midst of a meeting of the local Young Democrats and that two men running for the state assembly were vying for votes from this small body of activist liberals. The tininess of their endeavor enhanced by the greatness of their desire endeared them to me, and (after all) their politics are likely nearly mine, so I listened to their small meeting until they finished with it (even electing a new leader) and burst into their party. At which point they became not quite boisterous but engaged and happy, full humans in the enterprise of life. I do not know what lies made them so happy, but they were warm and long-lasting ones.

As the meeting was going on, I wrote a little poem, one modestly visual yet dependent on its visual presentation, and I wrote it but snatching words these young Democrats threw into the air. Pleasant words. Quiet words. Words they believed. And I made a poem that I think is wrawn well until its penultimate letter, which is where everything fell apart.

And I wonder if that flaw, if all the flaws within it, make it the poem it needs to be, the best poem this modest poem can be. Or if a flaw is just a flaw, something that tells you that you have nothing perfect before you and should move on to the next thing.

I bet the answer is the latter. But the former is the lie I want to believe.

(I had meant to slip into bed early tonight, yet I now see that it is nearly one in the morning, even though I would have guessed it was no later than ten. When we are entranced by words, by singing, by darkness and rain, by letters in a row, by white ice or clouds, by voices all around us, we sometimes forget where we are and who we are. And those are the times we wait for.)

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 26, 2012 21:48

April 22, 2012

We Are All Harnessed to Flesh, the Most so on Sunday

Geof Huth, Cultural Education Center, Northwest Corner, Ninth Floor, Empire State Plaza, Albany, New York (20 Apr 2012)

Geof Huth, Cultural Education Center, Northwest Corner, Ninth Floor, Empire State Plaza, Albany, New York (20 Apr 2012)Give me enough details and I’ll miss the whole.