Geof Huth's Blog, page 6

October 13, 2013

Ecstacist of the Pwoermd | Jacket2

I answer questions from Gary Barwin about pwoermds. As easy as writing a blog posting.

ecr. l'inf.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on October 13, 2013 14:59

September 8, 2013

Because Sleep Don't Suit Me Now

Geof Huth, "The Man Who Kicks the Bowling Ball Kicks Himself" (Albany, NY, 6 September 2013)

Geof Huth, "The Man Who Kicks the Bowling Ball Kicks Himself" (Albany, NY, 6 September 2013)We are made up out of so many incongruous pieces. A life is a congeries of contradictions.

I work as a manager, think as an archivist and records manager, breathe as a poet, exist as a simple complex thing called a person, and I am of one piece and pieces.

As we all are.

But sometimes, late at night, when I know I should be already in bed, I think. I think about what I am, about the doodles I make on agendas at work, about their roughness, about their sketchiness, about the fact that they are surrounded by notes for work, about their messiness, and I wonder what we know of ourselves.

I see people more than I connect to them. I observe. I evaluate. I am the Nick Carraway of my own life. I narrate, sometimes back to people, what I see. I sometimes know everything about a person on first sight—everything I need to know, everything I will hate or love about a person. Because I've been away.

I can do this because I've been away. I've been away from what people are. I am a person apart, a person, a part, a set of parts, a machine crunching away. We all are, probably. But it seems, sometimes, that there are people so simple in construction that they are whole, people who are simply their obvious selves.

Or maybe it is that we don't mean anything unless we contradict ourselves. I am, let's say

full of energy but full only at rest

smart but stupid

playful but disciplined

filled with irrational imaginings and grounded like a stick in reality

extroverted and introverted (and not sure which I should say I am)

Or you are.

I have been so busy with my regular work, and my extended work in archives that takes up many of my nights, that I seem less of a poet now, less of a maker, or maybe a different kind of maker now. There's a loss there, an emptiness from focusing on the practical and rational. But that is fully me, so I accept it.

It seems I have to accept that I've spent the evening trying to move my profession forward and thinking little of poetry. For this reason, I doodle these words on this screen. Not to poetize, not to make, just to be, to be a little more, a little more actively, to think, to scribble, to scribble again, to scribble my life back into assistance.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on September 08, 2013 21:06

September 2, 2013

Gate Wilder Squid and the Birth of His Idea

Gate Wilder Squid as a Pixelated Baby Kitten (December 1999)

Gate Wilder Squid as a Pixelated Baby Kitten (December 1999)[When my children Erin and Tim were young, I made up bedtimes stories about a cat named Gate Wilder Squid, and I would tell many of them over and over again. Years later, I recorded them into a tape recorder and transcribed them, later editing the transcription. This is the opening story of the series. (Later, in 2000, we acquired our own cat, a Manx we called Gate Wilder Squid as well--Gate, for short.)]

Now everyone was born in some certain way, and Gate Wilder Squid was no different from anyone else. Gate Wilder Squid was born in a shoe closet. Very few cats are born in shoe closets but sometimes it happens. His mother was in the shoe closet and she gave birth to him and to his brothers and sisters right on top of the shoes in the corner of the closet. His mother licked them off and cleaned them up and that’s how his life began. And for the rest of his life, Gate Wilder thought there was something special about that shoe closet. He would return to it and stay in the corner and rest in the cool darkness. But once he went to the shoe closet and he noticed the mirror in the back of it. Now why there was a mirror in the shoe closet no one was really sure because it was too far back for anyone to see themselves. And it would be even more difficult for anyone to see their shoes from there. But there it was. On this particular day, Gate Wilder thought, Well, it is pretty strange that there is a mirror there in the shoe closet. And he looked at the mirror carefully, and when he looked in the mirror very carefully, he saw a face looking back at him. Now most people would suspect that Gate Wilder was seeing his own face, that he was just seeing his reflection of himself. But as Gate Wilder moved, the reflection moved, swam through the mirror with him, always keeping up, never falling behind. Gate Wilder also looked at this face very carefully and he didn’t think it was quite his face. For instance: everything was backwards on the other face looking at him. And he didn’t think that he looked quite like that, and he’d seen pictures of himself, so he was quite sure it was not him. The wrong ear was bent down. He was a little whiter on one side of his face and it was the wrong side. And he was sure this had nothing to do with the reflection, but that it had to do with the cat being a different cat, and the world back there being a different world. So Gate Wilder paced back and forth, looking carefully, jumping around, sometimes seeing the cat jump around and catch up to him, sometimes missing him. But always the other cat was with him. And then Gate Wilder started swishing his paws at the mirror trying to get the other cat to do something. But the other cat swished his paw right back. And then Gate Wilder went over to the left, turned around and jumped through the mirror, chasing the other cat. And he kept chasing the cat, around and around, in and out of the mirror, from one side to the other, from one shoe closet to the other, back and forth, around, around, and duuzh! he fell tired on a heap of shoes and a pair of pink bedroom slippers. And he just said to himself, Well, there may be another cat there, but that cat never comes over to my closet unless I go over to his. And there’s never more than half of him over here when there’s half of him over there, so he shouldn’t bother me here ever again. So he said, That’s good, and I’ll just leave everything be. Then Gate Wilder thought for a second and he looked around the shoe closet and he looked out the back of the shoe closet into the hallway where the light was shining down from the high window. And he smelled the slipper and he looked at the shoes and he wasn’t quite sure if he was in his world or if he was in the other cat’s world. He thought he was pretty sure he was in his world. He thought he had kept jumping back into his world, but he wasn’t positive. Not quite. So for the rest of his life, Gate Wilder kept thinking, Is this really where I’m supposed to be? Is this really where I belong? And he was never quite sure because he was never quite sure if his mother was just the mother of the cat on the other side of the mirror or if his mother was his. But somehow he learned to live with it.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on September 02, 2013 14:03

August 20, 2013

longform minimalism

Today's Sole Surviving Photograph by Me (Schenectady, NY, 20 August 2013)

Today's Sole Surviving Photograph by Me (Schenectady, NY, 20 August 2013)I've spent less time than usual this year writing poetry or about poetry, but I'm not sure how quickly I can claw back to it, so I'll start slowly. Today, at work, I wrote a short poem, in one-second bursts throughout the day, ending the poem with four words I'd written yesterday.

My process is to take 5" X 8" black cards to work (bought with my own money) and to scribble down words or wraw out fidgetglyphs whenever I think of them. No cost to the state, and done in the time it takes to draw a breath.

So now I'm left with this weird fragmentary poem, and I'm thinking that this is the beginning of a new sequence of poems, practices in serial minimalism. Send word if any of the below makes sense. Or not.

on only one

a & of an

archiveses

eye see

who or how

anword

I like it myself, but I'm biased in favor of cryptic and fragmented.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on August 20, 2013 20:48

July 24, 2013

The Point

The most basic of all symbols, of all marks of significance, of all visual directions to the interpreting mind is the period, the dot, the point, the full stop.

Anything less than the point is the blank space, a character as important as any other (and more important than most), but one that serves merely to subdivide visual sentences into words.

So nothingness is important, but the point is the beginning of something, of anything, the movement out of nothing and into thingness.

The least poem possible is not a one-word poem but a one-character poem, and the least of the latter is this poem of mine:

.

And the joy of ultraminimalism is finding the finest point, and the making of the poem out of the slightest object of written meaning.

Even suspended in the center of an imagined white square, the point is more than nothing, and it is many things all at one.

At first sight to our minds familiar with the obvious, the floating point is an ending. We realize and understand that, yet it floats, centered horizontally and centered vertically as well, so we wonder about its endingness.

It could, it seems, be the opposite of what it as first appears to be. The point could be a beginning, maybe a tiny opening, into a tunnel, into a burrow, into an enlarging darkness. It exists, after all, as the only black point on the white field of a bitonal world, so it would be right to be merely a representation of darkness, a point of foreboding.

But what if we see the point, instead, or simultaneously, as a decimal point, as a symbol reverse-decimating the value of any unseen numeral to the right of it, and as a symbol that leaves whole any numeral to its left? What is the meaning of a poem of unseen yet felt and intelligible mathematics? Is it merely a poem about itself? as the best poems seem to me to be.

Maybe our mind increases the complexity of the mathematical meaning of the point because we read it punningly, we read it as a representation of its name without the production of its name. Perhaps this floating point is the representation of the floating point and, thus, is more than a point. It is a system representing numbers that are changed by the floating of the point.

We can also perceive this simple point as a dot, as a period repurposed in a set of letters as if the letters in a word could be decimalized, as if each letter of a word is a code for a number and the numbers spell out the words for us, although none of them is visible.

Or the point is not a period, not a piece of punctuation at all, but the completion of a letter. Maybe the point is a tittle, the dot that tops only two of the letters of this plain and Latin alphabet. But the letter is itself hidden from us, invisible except for its top, the tittle, the natural stopping place when writing the letter.

And we have only two choices that this letter could be: an i or a j. And the j is only an extension of the i, an elongated version of the i, who am I, the person, the poet, the thinker of and on the poem, for every poem is about itself just as it is always about the poet because the poem is an expression out of the body.

So we now recognize our vantage point. We are looking down over the dot. The dot is falling away from us and down, hurtling down. It may be the full stop ending a sentence or the period inexplicably opening one. Or it is a decimal, a floater, a tittle (and, in threes, the ellipses, the dot, dot, dot of the unended, the upended sentence). And it is falling.

But the dot is not the poem. It is the herald of the poem. It is the cause, and the poem is the effect that we cannot yet see.

And when the dot hits the flat water, it makes a sudden funneled splash, and then out of it come wave after concentric wave of expanding circles, a series of circles that replicate the shape of the period and that extend only away from the point of impact, each circle diminishing in strength and visibility as it grows.

Until every circle grows out so far that it disappears, and each subsequent wave grows out, each less so than the last, until each wave flattens into nothing, and the face of the water stills . . .

and we look at nothing but the blank white page we once imagined a period upon.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on July 24, 2013 20:56

July 17, 2013

A Poetics # 100: Matter

The Symbol of Poetry: An Empty Entryway to the Ruins of a Hotel atop Lookout Mountain (7 July 2013)

The Symbol of Poetry: An Empty Entryway to the Ruins of a Hotel atop Lookout Mountain (7 July 2013)The question is why poetry can’t matter. Why can it not matter?

Today, riding home, I heard, on the radio, words introducing someone. Her name bounced off me (as if names matter). I missed the place she was from (a likely insignificant place based merely on where her current professorship now traps her). I heard that she was a poet, that she was a poet’s poet, that every poet knows who she is (I had never heard of her before), that she was reviewing (I, with my poet’s ear and heartbreak, wrote “worried” here first, mishearing the word formed in my own head) the work of another poet.

She said a few words about the poet and about the poems in the poet’s book. I could not even concentrate on what she was saying—her voice was so earnest. She spoke as if she were filled with belief in what she was saying. And I am no believer, just a questioner, just a screamer into the night, just a voice building darkness. I am not driven by earnestness. I am not driven by belief, which is a fool’s method.

If you say, “Now,” I say, “When?” If you say, “How,” I say, “Hew.” Answers are words against the possibility of belief.

I began, slowly, but agitated, to speak to her voice spilling over me in the shape of the slime and slurry of putrescent belief. I began to speak against her voice, just her voice. I could not listen to what she said. Her voice pleaded for listening, but the sound of it repelled me. She was a famous poet, so she knew how to sound like a poet.

She sounded like a tinny death rattle up out of the throat, but given over in some ungathered and ragged rhythm. She sounded serious but in the slightest of ways. Her voice told me, “Give up poetry, you the people of Sodom and Gomorrah, you the people of Haddad and Hoboken! Give up on poetry because it will drain the life out of you. It will take your will to live and replace it with a sclerotic and arrhythmic drum machine. You need no heart anyhow. This place, this wretched earth is too dark, and darkening, for you to want to live in it, and poetry we have made it so you will understand that it is too unimportant for you to think about.

“Have a burger. It’s better for you. Or maybe a few pink-slime chicken fingers.” (And you thought chickens had toes.)

I almost calmed down as she nattered out of her body her perfectly perfect prose, her little sentences of no particular delight. But then she quoted a part of a poem, or an entire poem—I don’t know. I recall only that it continued for a while. And I almost yelled at the radio as Dave turned off the Thruway at Exit 25 heading west.

Dave said, “That doesn’t even sound like poetry.” I replied, “That’s because she’s reading over the linebreaks.”

I then raised my voice against the radio, which always brings me poetry to melt the fat front my body, to burn the skin from my limbs: “Read the linebreaks! Read the linebreaks! Why are there even linebreaks there, if you don’t read them!?”

The poem itself, even with its linebreaks intact in the form of glancing pauses, seemed terrible to me, but (again) I don’t know. I couldn’t concentrate on the poem. I’m not sure of the words. Because she read the poem in that careful poet’s cadence.

Say that phrase quietly and slowly (“careful poet’s cadence”), pronounce all six of its syllables softly, and you will be able to approximate this vocal characteristic. In this kind of poetry, the poet lives in a dream state (yet opiumless), and the poem is pulled out of the body searching for rhythm and meaning, because none can ever survive for long within that dead and dried thing called the poem.

Again I raised my voice at the radio, telling it that it had helped prove people why poetry is nothing, or less that nothing, a vacuum at the edge of nothing that sucks nothing away. I sat there, aggrieved, wondering how poetry could survive and suddenly understanding why it could not. Why our world makes a poetry that demands inattention!!!!

(Note the force of those exclamation marks demanding lack of attention!!!!)

And I’m not even complaining, ladies and gentlemen, about the Zimbabwean protest poetry that the morning commute east had earlier brought into my ears. Oh, I love the idea that the poets cared, that they thought they could make a difference in the world, but their words, spun out of early 1960s beat writing and full of clumsy whitticisms (note the epenthetic h) were destined to be as useless upon the face of the earth as they were painful to my ears.

I could not have been filled more quickly with sudden insight this afternoon about the hollowness of poetry had I driven through Eureka, California:

Poetry isn’t communal; it doesn’t bring people together to attend to the same sounds, to listen to words. Poetry is made for poets, who usually care less about poetry than those who hate it, because only poets try to kill poetry.

Poetry isn’t a skill; it’s a feeling. Poets do not take their craft seriously; they don’t believe in craft. They believe they can learn poetry on the run, that repetition builds the poetic muscle. They believe they learn how to write poems by reading them, rather than studying them, by paying attention to their wholes instead of their component parts. Poets try not to be mechanics, because they fear that if they understand poetry they will then be able to create poems.

Poetry is read aloud by zombies, their lives already taken from them by the virus, the poem, the deadliest strain running through contemporary life, producing poems of bombast without blast, love without loveliness, hate without hatred. Poems come in two colors: grey and beige (ecru having been killed off a few years back).

Poetry has nothing to say without understanding that poetry should have nothing to say. The poetry of protest is the poetry of the political without being the poetry of any matter at all. Even if your poetry leads directly to your death, you probably had nothing to say that mattered to anyone. Poets have lost the idea that the poem has to surprise the reader linguistically, to change the reader’s perspective, to put one in a state of delicious unbalance.

Poetry says too much, trying to copy the rest of the obvious world. It does not want a reader to be lost. And if the poem doesn’t tell well enough the simple hollow story of its self, then the poem will preface the “live” reading of the poem with a full explanation of how the poem is about a little-known Courlandian fable the poet had heard of once on a visit to Latvia but did not recall until a moment five years later at a bar in Brooklyn as a woman he’d never seen before (but eventually to become his wife) had walked into the bar, just before he reads that poem, which explains that it is poem about a little-known Courlandian fable the poet had heard of once on a visit to Latvia but did not recall until a moment five years later at a bar in Brooklyn as a woman he’d never seen before (but eventually to become his wife) had walked into the bar.

Poetry doesn’t care about the audience. Poetry hates the audience for not being made up completely of poets, even when it usually is nothing poets. Poetry is made by those in love with the sound of their words, but not in love with the sound of words.

Poetry cares too much about its audience. Poetry is a golden Labrador retriever, all tongue and tail-swishing and excitement, all eager to please, but with nothing to offer. Poetry is legerdemain, legerdecoeur, legerdemot; it is a magic trick that everyone can see failing—a rabbit picked up off the floor, the lady literally sawn in half, and screaming and trapped in that wooden casket now sodden with her own blood, her arms flailing but her legs moving only slightly whenever the entire box moves.

Poetry hates itself. It knows it is worthless. It knows it should die. It knows no-one loves it. It knows no-one will cry when it dies. It knows it will be cremated after death and sprinkled over the gently rocking waves of a toilet just refilled after flushing.

Poetry is clean, clean enough so you can eat off it. Poetry tries hard to avoid disturbing the reader into new thoughts, new ways of seeing, new ways of being. Poetry wants you to know what you know is what to know. It is a good friend, fat hand patting your back. You thank Poetry until that slender sharp blade slices through the skin, the flesh, and the bone of your back.

Poetry knows it can do nothing, nothing, nothing. Poetry knows it does no-one any good. Poetry knows it sucks the soul from the living.

Poetry is our resplendent, ravishing, radiant zombie goddess.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on July 17, 2013 19:57

June 7, 2013

Cavernous Hemangioma

Geof Huth, "ficious" (2 May 2013)

Geof Huth, "ficious" (2 May 2013)On May 2nd, I drove, near the end of my usual work day to see my neuro-ophthalmologist, wondering all the way there how I had made it to such a point in my life that neuro-ophthalmology had entered my life. And this was before the cavernous hemangioma.

Well, I'd know about it before.

As with most stories it began with nystagmus. I had to find the word, not look it up. I had to look up the condition without knowing what it was called. With me, it's a shaking of my vision, sudden, quick, unexpected. A shuddering as I might see in a horror film when the fright comes jagged. There is something frightening about impeded sight, even if only a flicker. My eyelids don't move, but my vision does. Sometimes, the vision shakes itself many times a day, sometimes only once.

I'm used to it now. It is nothing but a visitor, an occasional rumbling of the body, like borborygmus or flatulence. Something natural that comes from the body and evaporates it forgetting.

Still, I went dutifully to my second appointment, which seems more like an excuse to see me than anything else. It was, after all, a doctor's visit, so I spent little time with the doctor herself, who told me less about my conditions than she added to the sheet someone else gave me as I'd left.

Today's DiagnosisShe'd mentioned the cataracts and the macular degeneration, something it seems I don't want to wish for. Not because either will pose great problems on me or be insoluble, but because a visual poet needs his eyesight, so losing mine, even a little, would change who I were. Change, I might say, how I see the world.

Nystagmus Unspec (379.50)

Macular Degeneration Senile Unspec (362.50)

Orbital Disorder Other (376.89)

Visual Field Defects Unspec (368.40)

Cataract Incipient (366.12)

Problem List Updates

Visual Field Defects Unspec (368.40)

Orbital Disorder Other (376.89)

I did not even see this list until I made it home. I was amused that almost all of my ailments were unspecific or other. (Before my heart surgery, I was having "atypical chest pains," which seems to mean "plaque clogging the arteries around your heart," so wonder if it would be better to have a specific type of nystagmus, something I could put my finger on.

Instead, I have a carvernous hemangioma behind my left eye, and wrapped like the snakes around a caduceus around my optic nerve. The caverns of this clump of blood vessels are filled with blood. This set of them is likely benign and may do nothing to my eye, or it will make me blind in my left eye, or (I wonder if) it might be the source of nystagmus. It's not supposed to be the kind that can kill.

I'm not to worry about it, so I do not. But I think about it, chew on it, wondering how the blood moves within it, if it moves. Maybe it only sloshes about, trapped.

My doctor talked to me about this after I took a visual field test for fifteen minutes or so. I sat in the dark, chin in a chinrest, one eye covered, the other looking straight forward to a dot on a white field, and I hit a button every time I saw a flash of light, no matter how tiny.

Since my visual field test was good, according to my doctor, the cavernous hemangioma is not supposed to be affecting my vision. But when she talks to me I am blind, for them have widened my pupils to the point that I am Dondi, and my eyes cannot focus.

I sat in a chair, unable to see the face of my doctor. I sat in a chair, effectively blind, and I heard how unblind I was, and well. But then the sheet shows these new ailments, and sees trouble with a visual field test I supposedly did well on.

There was no reason to call back to ask about the discrepancy, to see if the doctor made more money for each diagnosis, or just for every test. I just sit and wait to go blind, or not, as I type in the dark, wondering why I can't write anymore.

Wondering if it's because I can't see right.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on June 07, 2013 20:12

May 14, 2013

past&present

Geof Huth, "One View from Work Today" (14 May 2013)

Geof Huth, "One View from Work Today" (14 May 2013)"So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past." --F. Scott Fitzgerald, novelist (1896-1940) Quoted from memory, though I always want to put "ceaselessly" before "borne." This quotation is one of the most famous lines in literature, the one that ends "The Great Gatsby," chosen in this instance since a new film adaptation of this novel is filling film screens at the moment. But it somehow speaks to archives because it speaks to the inevitability of the past and how we cannot escape it. The inevitable and inescapable might sometimes be negative, but they can also work to be positive, which is how I see things in the case of archives. These words somehow also remind me of a conversation from last week, one in which I said, "I have no interest in the past." As most sentences this was only true in a narrow sense, but the words caused my friend to ask me, "So didn't you choose the wrong profession?" I said, "No," and the reason I gave was that "I see archives as being about the future." Maybe I see archives as the physical occupation of the present by the future. (And, yes, even for digital records, which always exist in physical space.) The past seems somehow useless to me because it has been made inevitable, but what we do with that past in the present in the future, how we transform that past into something we can use, gives that past a living presence and, thus, great value. That is my focus always: the continuing present, which we sometimes call the future. ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 14, 2013 20:33

April 17, 2013

Today, I Stood

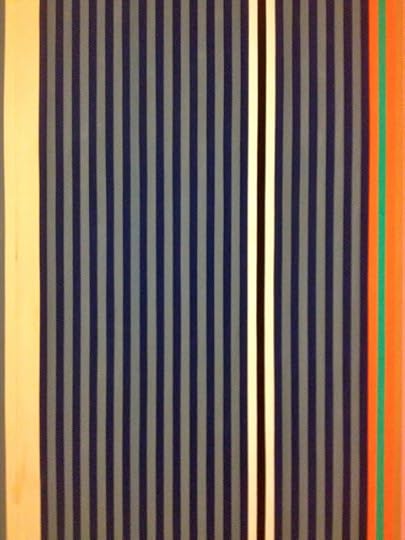

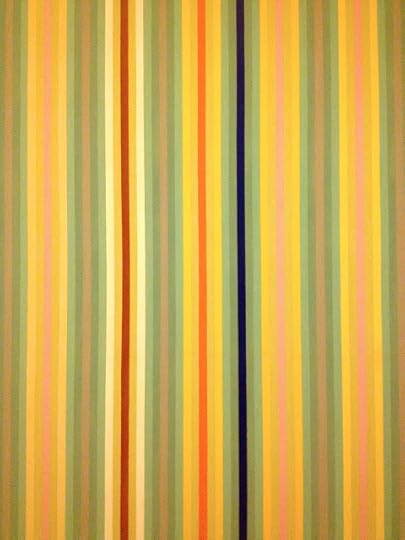

Today, I stood and stared, as I often have, at Gene Davis' "Sky Wagon," a painting from 1969 measuring nine feet and ten and 3/4 inches tall and 54 feet and 5 and 1/2 inches wide. The painting is too wide to appreciate in full in one eyegulp, and it doesn't work that way anyway. It is still beautiful, straight after straight vertical line of acrylic five storeys recumbent. In such a view, you see the colors as they change, you see the bundles of light colors struck through with a discordant line of color, but you don't live within the painting.

I work in a building that is home to a museum, though I do not work in a museum, but this is a museum focused on the historical, both human and natural, rather than art. To experience an art museum, I have to leave the Cultural Education Center in Albany, New York, and travel underground into the Concourse beneath the Empire State Plaza, which ties ten state government buildings together, so that we need not venture outside in the winter. And this space is decorated with some of the consists of the "92 paintings, sculptures, and tapestries that are sited in the Empire State Plaza concourse, buildings, and outdoor areas."

The art collection, the brainchild of Governor Nelson Rockefeller, himself an art collector, is an

interesting collection of art, with a number of great pieces and quite a few (particularly in that main Concourse) that are barely worth a look. But it is "Sky Wagon" that holds my attention. Part of the reason is its size. Another might be its extravagant use of color, often strange mixed shades. In the end, the reason is because this painting is essentially a piece of op art, a style generally of little interest to me, but one that comes to some kind of peak in this painting. And, I imagine, other such paintings by Davis, he of the Washington (D.C.) Color School.

The painting works, it does what it needs to do, only when you decide to live within it, only when you decide to look at it intently. Only when you give in. Although I've stared at every inch of this canvas (actually canvases, and quite awkwardly stitched together), my primary pattern of viewing is to go to the canvas, as close as I can, right up to the stretched line protecting the painting from viewers, and to look closely at a single dark line within strands of light colors or to look at a single bright line among the dark.

What occurs is a shimmering. The lines of the painting, so straight and prim, begin to shimmer as the multitudinous colors attack the eye at once. The combination of so many colors in such rigid arrangement cause this remarkable shimmering in the eye, nothing but an optical illusion. So it is like vision of any kind, but the shimmering and more-than-wide-angle-vision-wide width of the canvas pull me into the painting. I am not separate from the painting, as in every other painting I've seen in person; I am a part of it (not apart), I am awake in a dreaming and swimming through color, I am meditating and calm, I am one and me, rather than multiple and no-one, I am alive in the moment.

And I do not hear the state workers and visitors behind me shuffling back and forth that long corridor leading to the State Capitol and back. There is no government, no governor, no floor, no ceiling. No world save the deep and entrancing world of this color I can never want to escape. Though escape I must, and do.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 17, 2013 20:59

April 16, 2013

A Bauble of Color

The eye takes it in; the lungs then breathe it out.

At times, I say my favorite color is pink--because my favorite color is pink. (In such ways, we see how spoken language coincides with belief, despite the struggles between competing beliefs in the ephemery of self.)

Does the color of rust, almost red, add to the sense of blood, even in the absence of oxygen? If you scrape far enough through the pink, does green appear, or bare worn wood tinged with green? Who lives on that pink island in that shallow sea of green?

My eyes are working, you see, so I can take it; my tongue is exercising so I can make it. Speech is what comes after is. Not "it." "Is." Being in the process of being.

The senses are a swarm, not a handful. They are not separable as fingers. They do not precisely diverge so that only one appears at a time. I hear the sound of rain as I watch these words being typed onto the screen.

What that does is make me wonder who the watcher is who waits to see what words we type.

I can smell the scent of banana in a glass of beer with no banana. I can smell prunes in beer where none suspend.

You must understand, it is not beer. Not the various flavors of beer as if it were just a beverage, a liquid contrivance of human ingenuity to create flavor out of random events. It is that it is the be-er, the means by which the human experiences life as flavor, the twin sister of scent.

The ales don't ail us, yet we ail through them for we are the same be-ers as they.

Keep a mind straight on a thought, and you will see how it bends down, just ever so slightly, at the horizon. There is not a flat there, but the tension of turning, of a turning motionless but in suspected movement.

Even when you think your heart does not move, it beats.

It beats to be you. And you cannot beat it.

It can only beat itself.

My mother and father's favorite color (shared) was lavender, and remains so for one of them. My father would tell us this because it was what he believed.

If the world were made only of people saying what they believed, there would be no poets to show us how we had strayed from confusion into certainty.

Even now, I feel the dread of certainty, the fear of that clarity of purpose, something so pure it could compel us to kill, something so powerful it could unbeat a heart.

But, beet-red, it beats. It beats for both. It beats for blood. And it beats for bleeding.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 16, 2013 20:42