Geof Huth's Blog, page 5

August 4, 2014

An Amphora

something about the day after yesterdaysomething about thatsomething about having had it beforesomething about not knowing what to dosomething about carnivoressomething about the sound through sliding under the doorsomething about losssomething about adventure at a pricesomething about realitysomething about the heaviness of gravitysomething about desiresomething about the mandragora, the mandrake, the rootsomething about hoping for somethingsomething about something slipping through your fingerssomething about paralysissomething about arcssomething about the seven deadly sinssomething about the four horsemen of the apocalypsesomething about Eve in Edensomething about carousing before darksomething about my wordssomething about the escape of breathsomething about windsomething about the tension at the back of the necksomething about motionsomething about stillness surrounded by movementsomething about statuarysomething about corner of the coffee table and the center of her foreheadsomething about comingsomething about waking within a dreamsomething about whittling while whistlingsomething about soundsomething about a hatsomething about possessions over lovesomething about periwinkle in its three incarnationssomething about bloodsomething about tearssomething about garlic scapessomething about runningsomething about “verdant” and “abundant”something about prepositionssomething about extending a finger into a holesomething about wantingsomething about leavingsomething about the twelve stations of the crossedsomething about running to the other side of the streetsomething about the Avenue of the Wickedsomething about signs in timesomething about neonsomething about tropical fishsomething about drowningsomething about suffocatingsomething about hyperventilatingsomething about careening and careeringsomething about vertigosomething about living until the point of deathsomething about detachmentsomething about horses’ hoovessomething about quicksilversomething about a three-inch sliver of wood in your foot for three monthssomething about comingsomething about boredomsomething about extravagance at the expense of certitudesomething about institutions of higher thinkingsomething about beliefsomething about process and productsomething about ponderousnesssomething about boraxsomething about dessertssomething about wagon trainssomething about dyingsomething about constantly forgetting to remembersomething about losing your grip on itsomething about a modicum of moderation in a medium modesomething about swirling and twirlysomething about quaffingsomething about zeroing in on the littlest bitsomething about taking oversomething about us

something about the day before tomorrow

ecr. l’inf

something about the day before tomorrow

ecr. l’inf

Published on August 04, 2014 19:42

August 1, 2014

A Father Writes about His Daughter's First e-Novella, or XOXOXOXOXOXOXO

Erin Mallory Long, Text/Chat/Email, Part One, Chapter 11 (2014)

Erin Mallory Long, Text/Chat/Email, Part One, Chapter 11 (2014)Maybe it is that I think every book is a roman à clef, and every character within it is a character from real life. Or maybe I think every book is a roman fleuve, and the story within each extends for volumes, even if sometimes from outside the pages of the book itself.

Or maybe it is that I re-experience, within the words my daughter has written, parts of our life, because the only stories we can tell are our own.

All I really know is the my daughter, the Internet-famous Erin Mallory Long, a woman of great beauty and a woman of words (after her parents), is alternatively funny and devastating, that she takes a story that seems at first to be about the vapidity of young adults thinking their way meanderingly through their lives and slides the curtain so that we can see real people living real lives, tentatively and ferociously wrong, with kindness and anger. Maybe it is that she surprises me with her words.

As I began to read this e-novella entitled Text/Chat/Email (put out by Thought Catalog Books and available for download on Amazon), I also started to text my daughter in Los Angeles (I am in blue):

Texts 1-3

Texts 1-3 Texts 4-7

Texts 4-7It was an appropriate way to communicate, the way I usually communicate with my daughter, the way she lives. But it was also appropriate because this is a modern epistolary novel. Most of the story, amazingly, is told in text messages, electronic chats, and email. Brevity somehow works to tell this story. Short bursts of texts in short chapters, yet so much appears in so little space.

Text 8

Text 8 Text 9

Text 9I saw hints of Erin immediately in the main character Emily, and other echoes of our life. The focus of the work, though is twenty-somethings living through their meager years, and Erin tells this story with a command of that language (which is her native tongue, or thumb) that is almost shocking. In tiny text messages and chats, in only slightly longer emails, she develops a voice for every character. The book is almost more of a playscript than a novel because it is all about voice. And in our voices rest our character: the words we use, the ways we put them together, the intonation of them. What we have here is the creation of a micro universe of maybe ten characters, only seven of whom even talk, yet each of whom is fully real. Voice.

Erin Mallory Long, Text/Chat/Email, Part One, Chapter 11 (2014)

Erin Mallory Long, Text/Chat/Email, Part One, Chapter 11 (2014)As the story progresses, in so many ways, it seems to be somehow about my life--a fact I take no pleasure in telling. The main character is flawed, not fatally, and this is not a tragedy, but the flaw pulls her down, pulls her apart, removes her from her friends, changes her life, and she is left to wonder if she can accept her faults and move on. That sums up my life for many years now, and maybe only now am I living in Part Two of the book, the second act, the impossible part of an American life. In a certain light, I see this book as a sign of forgiveness. It radiates because it devastates, quietly, painfully, humanly, not outside of the bounds of a real life, but within a usual one, a believable one.

Text 10

Text 10 Text 11

Text 11 Text 11-13

Text 11-13

Text 14

Text 14 But all of the writing isn't in tiny bursts. There are a few diary entries from Emily, and scattered within this story are bits of free narrative that break into and out of Emily's head. The narrator, who is not even human, thinks for Emily, and then Emily responds to the thought, she picks up the conversation, she moves through it. An interesting device: how Erin wrests the narrative from the narrator and gives it to the protagonist, and then back, pulling us back and forth in a tiny dance of meaning.

Text 15-16

Text 15-16 Text 16-18

Text 16-18While Erin was writing this book, I was not in contact with her, didn't even find out about the book until after it was published. Then I bought myself a copy. I don't know that I could have helped Erin with this book, but I would have tried. But she didn't need me. Maybe the others in the family who read the book in progress gave her what she needed, but all I needed to be was a reader, because she's a real writer already, a person who hears voices and recreates them, a woman who grew up with a dachshund named Duck, so she ends the book with a talismanic gesture: Emily acquiring a dachshund puppy whom she calls Duck.

As it should be. Our art should follow our lives. Our lives should be our art. But what do I know? I'm only her father.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on August 01, 2014 20:29

July 29, 2014

Goodnight, Mrs Mike, Wherever You Are

The View My Mother-in-Law Would Have Seen if Only She Could on Her Last Full Day Alive (15 July 2014)

The View My Mother-in-Law Would Have Seen if Only She Could on Her Last Full Day Alive (15 July 2014)A eulogy is rarely ever focused on the missing person; the eulogy usually concerns the interface between that person and the eulogist. In that way, eulogies are essentially autobiographical.

So we go.

Everybody dies.

The trek by which I ended up alone with my mother-in-law in Amsterdam, New York, on the last full day of her life was a circuitous one. And one has to work through circuitry backwards from the point you begin. One has to work in circles, circuitously, circling, finally cinching it all tight.

Follow the humming.

Nancy texted me at work from Los Angeles that day: "FYI Dad says Mom is getting worse and that don't expect her to last long. Might be gone by the weekend but who knows. Dad says no services or anything. Just wanted to let you know." At this point, I had just learned my mother-in-law, Mrs Mike to me (though that nickname has nothing to do with any of her real names), was in the hospital. With a few other scraps of information, I had determined in the previous couple of weeks that she was frail. I had already worried her body would soon desist.

For the body cannot resist the pull of death.

The time was 3:30 in the afternoon. Three hours later, I would have finished work, driven to my house, fed my pets, driven to Amsterdam, and seen Mrs Mike. There was not much left to her. A bit more than a month older than 84, she looked almost as thin and emptied of life as my grandmother did in her deathbed on her hundredth birthday. Almost no muscle to her, just brittle glassine skin draped over what seemed then to be small bones. Her head was propped up by two pillows and the raising of half the bed, yet her breathing continued only shallow and labored, her mouth both wide open and askew.

She couldn't speak, she couldn't hear, she couldn't know. I understood all of this before I'd left to see her. I knew there was nothing to speak to, yet I had to go. So I didn't speak long. I talked to her softly, calling her Grammy whenever I needed a name for her. I petted her hair, kissed her on the forehead, said goodbye. I apologized for all I had done and the pain it had caused her family, even though she had never known anything of this or how it all had hurt the people she had once loved, when she was capable of loving. I held her hand, moving her fingers as I had moved the fingers of my dead mother before we buried her in a hole too small, at first, for her casket. I felt her stockinged feet through the bedclothes, and they were cold to my touch. She couldn't warm her body in a warm room. Her body was shutting down.

I think I was the last person she knew who saw her alive, but I can't be sure because I have so little information about what used to be my family.

On my way out of the hospital, I had to dodge a family with a couple of rambunctious children. The elevator empty save for me. The first floor of that end of the hospital eerily absent of people, entirely so, as it had been upon my entrance. By the time my foot hit the parking lot, I was beginning to cry, only letting all the tears out at the point I shut myself into my car.

The text I sent to Nancy explained for me: "She's so frail. I'm bawling. So much loss. So hard to see her but I was desperate to see her. I've lost my family so I wanted at least to say goodbye."

I was in darkness for a week or more afterwards, the talus slope of my life sending me sliding. In the middle of last month, I had found myself in Iowan countryside for a week, surrounded with people, but without the antidepressant that keeps my body, my psyche, my unified body-mind self from crumpling slowly under the weight of even the thinnest air. And I waited almost a week longer back in New York before the insurance company would replace the medicine I've never been able to find, don't ever recall receiving.

Before my trip, I'd understood what had kept me so sad for so many years: the simple fact that I had lost my family because of my own mistakes. (Intentional mistakes are still errors.) Though family is a complicated concept for me, and I'd deserted my original family slowly over those so many years, finishing it only late last year.

In the madness caused by holding out hope for the possibility of rebirth, I had a plan to work slowly to repair the damage I didn't want to have caused. But I saw the folly of that early enough.

The ironic fact is that Mrs Mike and I did not exactly get along. I push against people who push against me, and she pushed me for so many reasons: I wore an earring, I married Nancy, Nancy was pregnant before our wedding, Nancy wasn't her favored daughter, I would quietly leave the porch when she started smoking instead of staying there and appreciating the stench. And I also pushed back.

The annoyances she provided me, however, were often humorous. I would upset her very easily with my teasing, causing her to give me the finger nearly constantly. Just a middle finger popping out of her hand, without two folded fingers astride it to form the testicles. I didn't know how she did it. And if I tried to tell her that that gesture had a very specific vulgar meaning, she would insist that all it meant was "I don't like what you're saying."

"When I use a gesture," Mrs Mike would say, in rather a scornful tone, "it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less."

Well, not exactly her words. But I can assign words to her now.

She would also swear at me. I'd say something, anything, and she'd say, "Bullshit." Very quickly. This repetitive feature of her vocabulary became even more common as she sifted into dementia. She would whisper, use it more frequently, speak it quickly, and not even direct it at anyone. She would simply repeat "Bu'shit. Bu'shit" over and over. To herself.

The word as talisman.

So when I told people I know that my mother-in-law was dying, and later that she had died, they didn't try to comfort me, noting instead that she had been a thorn in the side of my life.

Which she had. But she was my family. Part of it. My own mother dead for fifteen years now, my beloved aunt for a few fewer, Mrs Mike was my only mother. When I was texting Nancy about wanting to her mother, I had explained this to her.

A week or two earlier, I had tried to see my mother-in-law. As part of making up for my life over the past too many years, I had started to apologize to people. First to Nancy, then to my son, finally to my daughter. I had to say how sorry I was for what I'd done wrong, but I also had to show how what I had done fit into the context of what I'd allowed my life to make me.

So I also called my father-in-law to see if he would talk to me and so I could say goodbye to my mother-in-law, whom I thought was near death--though I was merely guessing that. My son was in town, and I thought that I could see these members of my family if I had him with me. When my father-in-law answered the phone, though, I panicked, and said, "Hello, Mr Mike." His voice, at first jovial when answering the phone, turned immediately cold and pinched. I could feel the hate in his voice, and if not hate then extreme dislike. He had a reason. I had hurt his daughter deeply once. Many times.

(Though we had hurt each other. Lovers often do.)

In the background, I could hear Nancy talking excitedly, happily, so I guessed she was there with a new friend of hers, because she could not have carried out such a conversation with her mother. Her mother had become silent by then.

At the time, I didn't know this, but my mother-in-law was probably already in the hospital by then.

I quickly apologized to my father-in-law for calling him and said that I would write him a letter. I haven't written that letter yet. It's the last of the first wave of letters I have to write to people. I have no other people to write to, only waves of letters to the same few.

I am a person of modest numbers of intimates.

But I won't write any letters to my family of origin (to use one of those awkward psychological terms of art). I gave up on them entirely during my father's 75th birthday, found it so painful to be with those damaged people. Found them toxic.

The older I become, the more I see the world as a collection of ruined people, some more deeply ruined than others, and every member of my family of origin, even me, especially so--my siblings by our shared childhood, my parents by their own. And the collection of these freaks of unnature and their nastiness and manias were too much for me.

I've written about the days around that 75th birthday celebration, so I don't need to write about it anymore, don't even need to explain why I won't answer any messages from my family of origin, why I had to send my father's arch conservative email tirades directly to trash (without ever allowing them to darken my inbox). Or why I, in a time of great grief for him, I called a brother I don't even like, my gay brother (outed by his daughter's accidentally discovering this fact) to help him and listen to him cry about being abandoned by his children and being told by my father to find help to cure him of gayism.

I made of up word "gayism." Even if it existed, my father would not use it. He'd say "faggism."

I've separated myself from the toxicity, and maybe people are separating themselves from my own toxicity.

Attraction, repulsion, the variations of human magnetism.

On the day I went to see Mrs Mike, Nancy told me that her mother would be cremated, there would be no service, and that there wouldn't even be an obituary. This bothered me because I'm an archivist, a records manager, a genealogist, a documenter, a needer of records, and I felt a void in my mother-in-law's disappearing unremembered, undocumented.

To me, it seemed that her death was met with relief more than grief, and I understood that. I felt it, too, though only dimly. I had seen her demise resolve itself over time. I had seen the years of dedication my father-in-law had donated to her, seen how he took care of her alone for years, every day, every hour, through all the conversationlessness, through the incontinence, through the diminishment of his wife into a hollow shell of breath. The loss of his wife before she even died.

I tried to convince him not to be her sole caretaker, but he wouldn't listen. He lived through some grief during his life with her, but I imagine some love as well. And he is the most decent person I've ever known. He is a sacrificer.

And I've missed seeing my mother-in-law these past few years, so I missed her more than others because I did not experience the trouble of being with her. I know that. And I know that her family, what once was also my family, is now tired of all the years with her and with her so gone, so unpresent.

I understand the pain of losing something when you can still see it.

So I'm reaching out to the tiny bit of family I can and will still claim. I've written a long letter to my son and daughter explaining how I had become something they could not understand or accept, and I've waited for a response. I can say, at least, that my two beautiful and brilliant children are tentatively and occasionally within the orbit of my presence. It is a start. A relife.

A relighting.

Maybe.

Two weeks dead, a fortnight by some accounts, to the day, and my mother-in-law seems a thing long past, a recollection of a loss, a vague ache for something ineffable and almost unremeberable. Still, there is sadness, the sadness of looking at her dying and seeing in that dying the death of my family, the family I had helped to make, the family I had wanted my entire life, the only thing I ever needed (but couldn't realize soon enough that I had needed).

My body, unconscious, had helped me make a life my mind could not understand it so deeply needed so that I could thrive.

I am slow, just a child in some sense, so it took me too many years to figure this out, to understand the simplest of things: how I felt, what my emotions were, what I had yearned forever for.

Now I have sadness to guide me, and a different life path to make. I need the machetes I used in Barbados to cut through the sugarcane and find a way out. Yet there is something good about all of this. Sadness allows us to realize our humanity, to feel something sharply enough so we know we are here, present, sentient, alive.

And I am, uncomfortably, relieved, in only one way, that there might not be an obituary for my mother-in-law, Mrs Mike, a daughter of Ireland (and Alsace, though she liked to ignore her Germanness)--because obituaries list the survivors, and because

I realized I would not be a survivor.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on July 29, 2014 19:24

March 14, 2014

One, 1, None (Eighth Draft)

Geof Huth, "The Notes I Write to Remember My Life" (13 March 2014)

Geof Huth, "The Notes I Write to Remember My Life" (13 March 2014) See a seen.

A shape inviolate

of wonder often has possi

bilities unthought.Numbers expressed arean orb extended. Raysrecall an orchestral set. The musiciancan do whatnot, exploringmusic.

To restrict—district—them, a scatteredcantata, a tested symbology,two beautiful songbirds are wrapped,caged, &

freed, released toextension, allowedroom, extrapolating that value encompassed via

motions, thoughts, a simple cusp,

intent of accident,stasis in

glorious manifests,englobing, arousing, merged in, entirely

one. That becoming, anocean via duct:to 3, 4—counted,

adding reality, intention, removing it, asubtlety.

Subtlety moving around, away, to convince, to see . . . .

fisher, finder, what fingers

eradicate, and foreskin,just what oceans

encompass: beach, reach,

tense reaction to it.Was I enraged by seven or seventeen ways?

Relative I be, relative werenumerals: 9, 8, 7. Foreverwere these

to encroach from 1

to another,

a resistant sea, ecstatic sways,to a 1.

Waves, waves, waves,undulants, silver that must alwaysbe as blackened

suns, constant, radiating, cooled,thus penumbral and

and opening a carefully formed hole intoan expected movement. A

signifier extends every motion(motion again). Destitute, our aimmust then reveal a or numerous ways(version sings slowly)that meanings beall our febrile reactionfeebly creates. Dawdling,and a motion moveson several: I am

a dispersed,

disturbed, alost pearl, wrecked,taut, achingly found.Reveal, dispel ponderousor, say, just limpid

ore, that sickened, waste&

fast depth that can be little, little more tortured by 1 way,our injurious way:curtly.

Scented, an orange,

or even essential,a same, O, an olfactory way, distant, toeven fewer memories,serials:

blendsblonds

blandsfor a sense, hints, devotion,demotion,a hurried time,faceless,heedless,a fever to

eradicate,to

imbricatescents, toremember, todismemberan often made

reversion, aversion, a verse forvision, made forsimple hungers,handmade, burnished,or piledpresently:

our motion

a 1for our

fewer:our

manys haveexpanded,extendedto

make twelve timids tame , to1, and severals madea beam. Plenty sharpened nails I sharpened more, & every 1 a sliver.

Extension madeher how

fever severed it,severed.

Any person makes money.Altogether

_____

I didn’t work on this piem enough today. I didn’t set enough time aside for writing this today, but still I am increasing this piem, this poem constrained by the numerals in pi. I work on this slow-to-write poem only one day a year (and I didn’t even post my results last year), so it grows slowly, like coral, like flowstone, and the direction of the poem changes. The words don’t go so much forward as awry.

ecr. l’inf.

Published on March 14, 2014 20:31

March 5, 2014

Self-Publish or Perish

Geof Huth, "BIRD" (2011)

Geof Huth, "BIRD" (2011)I was walking today.

I haven't been walking much recently. The bitter cold discourages me even though I feel the cold less sharply than most do. But I walk. And today I was walking.

As I'm apt to do, I was thinking, but in a wandering, directionless way. Somehow, I thought about poetry publishing, maybe because I'd read an announcement today about a book of poetry to be published, a book that won a contest (out of a set of about 450 books) to be published.

I'm not one to enter contests of any kind, and I've entered book publishing contests only four times, twice because I was young, twice because I was invited to. No book of mine was published from these efforts.

What the announcement of one-in-450 to publish a book tells me is that poetry publishing is hard to come by, if you care about status, if you see poetry as a career.

I don't. Never have. Poetry is an urge.

Earlier in life, back in the 1980s and a little into the 1990s, I used to submit work to magazines all the time. Doing so took enormous effort, and constant, but I had credits to my name. To some degree, I had people who knew who I was because of that. (I knew this best when someone parodied my work. I didn't mind being parodied. I loved it.)

In the last six years, I've almost never submitted poetry anywhere, because I hate the process, I hate the time wasted. I'd rather write. So I have. I've written many books, actually. At least first drafts. I've begun a large writing project that will sometime be a set of about twenty books.

So my idea is to begin publishing them, under my own imprint--dbqp--a press that's been dormant for years. Since I always want to design my own books, I might as well take over the publishing of them as well.

It's an idea, at least. Somehow publishing can be an act of writing, an act of art, an act worth my time.

Maybe I'll even do it.

Poetry is an urge

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 05, 2014 19:02

December 27, 2013

Christmas Day (December 27th)

Jack Kimball, "Holiday Greetings," 18 December 2013

Jack Kimball, "Holiday Greetings," 18 December 2013Every Christmas day, I look to Jack Kimball for inspiration (even in this year of virtual non-blogging) for inspiration, because Jack puts out a holiday greeting on his own blog pantaloons a bit before Christmas this year. But this year, Christmas wasn't on Christmas for me. All of my children did not arrive for it until the afternoon of the 26th, and the slow yet intense process of opening presents requires at least five hours (this year, five and a half), so we had a Christmas morning on the 27th, Boxing Day's Boxing Day.

So why do I turn to Jack for a Christmas posting each year? Mostly, because his contributions are steady in this realm (one appears in plenty of time every year), but also because he focuses on Christmas in a twisted way, and importantly because his collagist creations using words, images, kinesis, non-linguistic symbols and whatnot always surprise me and always challenge me. Because, in short, I'm usually at a loss about what to say about them but I'm entranced by them enough to need to say something.

The first you see this almost wordless collage, you think you are looking and an unfolded Rorschach test collage, a collage digitally pasted together then folded against itself to produce its own mirror image. Look above. The variegated leaves of some clearly tropical plant bookend the collage, but the leaves on one side do not replicate those at the other. Maybe this is the same plant, maybe it is not, but we are let to see a duplication, a duplicity. We are tricked into believing something calculably untrue (think Christmas) by looking at plants with no cultural connection of ours to the concept of Christmas at all.

The collage, arguably, is designed to be read from the outside in. These bookends force this view. And if we see the collage in this way, we notice that the details encumber and increase in detail as we move our eyes into its center. Smaller images, variously rectangularly shaped, overlap each other and the two bookends, and they also hold more detail: more leaves, more shapes, and even words for the first time.

We are tricked again--duplicity again--by two false centers, two lines created to "bisect" the image as a concatenated and congealed whole. One of these is a shadowed line a bit to the left of the center of the image. It extends beyond the natural bounds of the image, that border that retains the various rectangles of the image. This is the most obvious false center. But the other is to the right of it: a dotted line (light green and dark green alternating) that appears created by the inexact overlay of rectangles. It seems to appear because images below the top layer of images have not been perfectly covered. This line is duplicitous, as is the hand of Kimball. The line is a thin slice of another image, maybe an image of the same plant that ends each extremity of this wide image. This is an intentional borderline, a deliberate fragment, an abbreviation of the whole.

What these lines give us is a triptych, which must remind us, during yuletide, of the trinity, the three independent being (one a father, one a son, one an evanescence) that are also simply a complete whole. We are reminded of a mystery, which we know to be a falsehood. Faith being false. Something unbelievable but true, meaning we know it is a lie, but we may believe in it for the beauty and comfort of belief.

So we flip through the leaves of this image: tropical, then pinny pine leaves (needles) with the evergreens shown upsidedown to tell us they are not true, they are lies, they are false, they are Judas on the cross. Hands appears, which are things that make things and hold things. Faces appear. Books of poetry. Gay men, outsiders yet inside of our culture, yet integral to our world--a message of difference. The message of words without the words. An idea of difference as a view of similarity.

The evergreen is actually every tropical tree--we just never remember to think of it that way.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 27, 2013 18:50

November 10, 2013

In the Land of O₂

We sleep in darkness even when the light is full. We live in a bubble of light inside the greatest darkness.

The moon rises over the left shoulder even as the earth rises over the right. Yet the moon next might lower over your right. Sunrise is always simultaneously sunset.

Head east far enough and you will reach the west.

Only gravity gives us perspective. Without our feet held to the ground, there is no up—only around.

Gravity is our tether.

When the tether gives, she rolls and tumbles—her voice possible only because she is living in a bubble of oxygen, a bubble of light. She tumbles towards the great blue light, sometimes up, sometimes down, only her feet tell her which.

We live in a bubble of oxygen so small we can breathe it all up. And we breathe it in. We take it down into us. The heart beats to the quantity of oxygen we have left.

If tethered to a person, we feel its tenuousness, its temporariness. The tether can break. He can release her from it and fall down back to the earth, or up, through its clouds and into its single ocean, leaving an ocean of blackness for an ocean of water (hydrogen doubled and paired with oxygen).

If she can make it back into a bubble of oxygen, she might live a while, looking up into the oceans for hope. She might believe the darkness is her hope. She might seek solace in its great black mystery. She might hope to know it is something else.

But it is an empty blackness she passes through just as we pass through our dreams. We do not live in these dreams of ours, even as they haunt us. We live through them and wake to light, or we dream through them to a timeless dark.

Enough black, and we dream some light into it: A face at a porthole. A great happiness of a person filling a pod. A story too amazing to tell. Sometimes, we dream our way out.

Even as she falls, she hears the music and crackling, the singing and the scratching of a voice, something sublime in the old sense, like the smell of grass cut in her pride. She hears the distant echoing voices of the earth coming back up to her. And her voice drifts down, in pitterings, through these voices cutting up through her and moving, forever, on past her.

The music tells us who we feel we are, but eyes are wells of darkness, for we can see only from within our own dark reaches. Yet our hearts beat against the music as the waves beat against the beach, and we erode finally into our selves.

A drop of water will hit the lens of the single eye watching her and splatter, but her tear will drift through that lens and out deep into the darkness that separates us. It will rest so close before those of us watching her from within our theatrical darkness that we will believe we can can reach out our hands and catch it, hold it, letting the liquid seep into our bodies.

The tear in the darkness will grow larger as it nears us, because nothing is ever only one size, because everything differs in size depending on how close it is to us. The tear in the darkness eventually becomes another lens, and we can see her, murkily, through her own salty ocean of a tear.

Every tear is an ocean to the one who drops it.

We can taste it is so.

If she falls, she falls through air, she falls towards earth, and the friction of air, the friction of a lighted something in place of a dark nothing, makes a great fire, a greater heat.

As she falls through fire, she falls to earth, she falls towards water, she falls into water. Now, made suddenly heavy again by the pull of gravity, she swims in a wet darkness. This time, she swims up towards the earth, towards the light, towards the place where saltless water laps upon the sand.

And she is surrounded by a great light surrounded by a greater darkness, but her heart beats steady and it beats slow. She is held in place by the gravity of the place.

Then we return to dreaming.

As we are directed to do.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on November 10, 2013 19:38

October 23, 2013

In the Arena of the Visual and Literature

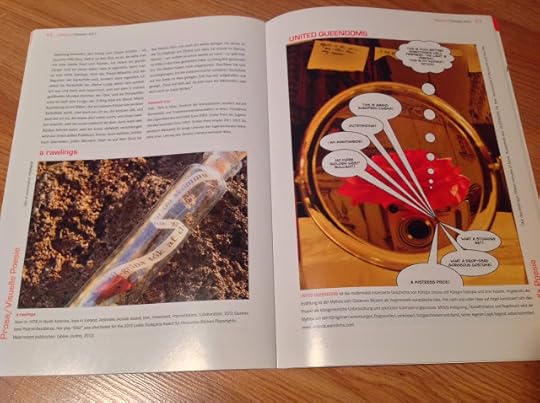

LitArena 6, pp 42-43 (October 2013)

LitArena 6, pp 42-43 (October 2013)We come out of darkness—and it is the darkness inside our own mothers.

Created in the formless dark, we take shape only within the light, eyes squeezed pudgily shut, hands in tight fists shaking at the new bright cold.

Slowly, the world takes shapes, we open our eyes, we learn to focus, our fists relax into working hands, and we make things with those hands for the benefit of those eyes.

And sometimes what we make are visual poems.

I am left sometimes stunned by beauty, because I could not imagine it but there it was.

And visual poetry can work with the beauty of the word, the image, the wordimage, and context.

The Austrian magazine LitArena has just published another giant glossy issue, and it includes, scattering within its light-shattering pages, about 20 visual poems, all of them given enough space to breathe—and us enough space to see them clearly.

I think of a rawlings' blown up greater than its natural size so that we can see the stoppered vial of glass filled with polished and drilled stones and a slip of sinuous paper with Icelandic written upon it, and I think of her moving from Canada to Iceland and working in a new place and placing this vial upon a volcanic rock.

And so many others.

I was suprised even from my piece: slip of a photograph pulled off an iPad's running screen, with a few words laid upon it needed, and I saw how conventional it was, unlike so many others within these pages, but I thought that the conventionality was what made it unconventional, and I heard my voice, punning the word out of existence, coming through the words and the smudgy-neat imaged I'd made.

And I tell you all of this, even though you may not ever see a copy of this magazine, just so you know it is there.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on October 23, 2013 20:05

October 21, 2013

No Shoulder, No Peace

Responses, collected from waxy shards of hearings of the words and meanings of a reading of poetry given in Kingston, New York, on 19 October 2013, by John Bloomberg-Rissman, introduced by Anne Gorrick introducing Lynn Behrendt reading. No poem is meant, but made, in the running of these words.

JBR

Painted bodies assembledas the dissembling disassembles us—the wrock

in the anaphora of the ofin the anaphora of the isin the anaphora of the itin the anaphora of the oh

shouting in the roaring brook, the castlefrom which we tear the page of lavender,out of which a slip of perfume falls—

the weight of it

against the wristleaning into the pulse of it

between piss and shitwe are born and we are dead

living against this catalog of colors(blue magenta teal opal onyx maduro)we have all of these

isn’t it?isn’t it?

in the mechanical of the arm of manin the mechanism of the leg of womanin the machinery of our open mouths

“in the not just and more than”in the not much and more or less

filled in by accumulating imponderabiliaashes dust powder flakes

in the scroll from which we have slowly extractedword by wordthe word

in the neural medium that distinguishesbetween white and wrong

in the alphabeticalin the eroticalin the ontologicalin the labyrinthical

of the windof the breath

something in the sadnessbetween father and daughterin the paralysis of love

something alive that doesn’t move but moves

all the good parts are hers

The eye knows it

in the empire of the hangman

the word that is missingis the word that is true

John, I said,which was his name,what speed is this you do?Can you slow the watch?

Can you smash it?

John, I said,which was his name,can you drive now?

in this onein one hugein one huge collagein one huge of words and phrasesin the sampled lifein the exampledness

replete

Patrick, which wasnot his name, I said, can you hat trick?

My little ponyHow shiny bright

tripped overthe semi-quaverthe hemi-demi-semi-quaveras a bird would wontwere a bird wont to

in my room I am in itin my place it is my only place

my muy

mixing a heating balm,palm of the fronded finger,warm movement—handin to the wind

Have mercy on meme into a less differentiated oneinto a one different fromthe other by all similaritiesshared and shared alike

I’m in it for the cosmogonyAnd against it for the same

in the last question of it

“How golden then is this” statute?

What rite have we in manners of estate?

John Bloomberg-Rissman, Possibly Praying at a Restaurant

John Bloomberg-Rissman, Possibly Praying at a RestaurantAG

Here I have said, asI have said, which was not her aim, two of the two, who are also ofmy work, in the importanceof it as it and as it is.

Sushi and Sashimi

Sushi and SashimiLB

You are hereHere you are

in the restroomin the bathroomin the washroomat the rest area

Here you arein the anaphora of your words in yourplace in the wordsyou are in placeof words | your self

Question:What did you found in the box?the lid of whichyou lost, opento the sun

Were it an armyof small plasticsoldiers smellingof crayons andsunlight?

Were it an empireof miniscules largeenough to lift thewind from its hinges?squeak at the leastheft of it

Were it how youshoved who youshoved what youshoved into theempty box youshoved it all into?

Filaments maybeto knit your thoughts togetherwith the light of sent voices

Scent of the bridges that morningskyed into a city broken into type

hellvetica garamound truncheon

it is a sad fact against a wordpage the pockmarked wordpagethe wordpage lost to the meaning of itself

I smell myrrh on the wrist of your pulseand the vibrant pulse of katydid and what she—

veins of green blood pulses of bok choy

to contradict the lucid gridthe map that makes the real

living in reel life

hands in the way on the parking lotin a holding pattern

of an eye on himof an ear on herof a touchèdness

more sea in the pastthan decade in the year

What we swallow?as belief, as beforeas a coming intoas a realization as a matter of fact

if

and in my crazy grass stylehandwriting calligraphy scrawl

the beauty in the ugliful

the eye is fixedand now can roam

I think breakfastbut it is intimacy

I think kiss but it is awkwardness

and in his slow ridingin the morning

horsetails of inkslow horsetailsin slow horsetails of ink in the morning

As a poem, I amconceptual. As apoem, I am lyrical.

tiptoeingthrough the dreamtiptoeingto keep it from beingtiptoeing to keep it from real

life along the estuary

the water that comes in | goes outthat water that goes out | returns

Nobody believes it

I’ve tasted itThe water tastes of tears

ecr. l'inf.

Published on October 21, 2013 20:31

October 20, 2013

Electronic Literature, An Attempt

Months ago now, I received a hardcopy version of Electronic Literature Collection, Volume Two, which included my main work of true coded digital poetry, ENDEMIC BATTLE COLLAGE. And I'd meant to post a few words about it, especially since it was interesting to receive a booklike object (with a USB stick in its center) to hold and represent digital poetry. The editors had a point with this. Parts of the world do not have good Internet access, so digital poetry is actually easier to read from removable media.

(Note that I've Highlighted My Piece, So You Can Find it More Easily

(Note that I've Highlighted My Piece, So You Can Find it More EasilyMost people, however, will keep going to the ELO II website to find these works--as you can do right now. There are many interesting works here, even mine from 1986 and 1987. (I have to admit that my initial poems are quite simple, but the final piece is quite a bit more complex than the rest, because I built up my coding skills as I wrote these poems.)

The other day I received a request, which all other participants in the Electronic Literature Collection series (numbers 1 and 2) received, to answer a few simple questions about my point of view about digital literature. Below are the questions and my answers. (As a documentarian, I had to save them.)

Author Survey, ELO Collections Vol I & IIWhen creating those poem(s) included in the ELO Collection, what were your reasons for choosing the technologies that you did? I was making my poems in 1986 and 1987, so there were fewer choices. The few people working in digital literature then were most frequently using Apple Basic on Apple // machines, and I followed suit. Doing so allowed me some extra benefit, because I could see how others had coded their works, and I could then use or build off their solutions.

As a writer/artist working with digital media, do you take into account issues relating to reusability?

Since I was doing my coding early on, in digital poetry terms, reusability was almost impossible. I was writing for Apple // computers running on an operating system different from those of both Macintosh computers and regular PCs. A very specific computing environment was necessary to run my poems. And this was the environment in which I expected users to interact to stop them from running (they otherwise ran on a continuing loop) and to read the code for more information, to understand the fullness of the poems.

The Center of the "Book," Where the Content, the Thumbdrive, is Visible

The Center of the "Book," Where the Content, the Thumbdrive, is VisibleAs a writer/artist working with digital media, do you take into account issues relating to obsolescence?

As a writer and an archivist, obsolescence has been a huge issue with me when dealing with digital poetics. As bpNichol noted in the introduction to "FIRST SCREENING," the digital world has thrown us into a Babel of programming languages and (at the time) of huge incompatibility across platforms. So obsolescence was a huge problem for me, one that I dealt with in three different ways: 1. I saved the actual code on disk, which allowed me to run the poems in an emulator decades later; 2. I saved a videotape recording of the digital poems in motion; and 3. I saved the code as printed text, so that I could recreate my poems in the future if I needed to.

As a writer/artist working with digital media, do you take into account issues relating to production and maintenance costs? I work as cheaply as I can. These days I don't work in full-scale digital poetry anymore. I don't code anymore, but I work digitally in poetry constantly, working instead in social networks, working with human-to-human interaction, rather than human-to-machine interaction. I make things small enough so that I can maintain them, but I imagine that more complex digital poems will be more difficult and expensive to maintain. On the subject of technologies (software and/or hardware) being adopted by digital writers/artists, is there anything else that you would like to add?

What serves as the shaky foundation of digital poetry is the ever-changing technological landscape of the modern world, one not designed in any way to support digital poetry, but one that digital poets have learned to operate to their own advantage. The unfortunate part of these technologies is that they do not have the means to support access to interactive and kinetic content over time. We have reasonable methods for freezing in place static content, at least until the next era of obsolescence, but we have nothing like this for true kinetic visual poetry.

The Back of the "Book," Where You Can See that the Editors Misspelled My First Name as "Geor" (Geor?)

The Back of the "Book," Where You Can See that the Editors Misspelled My First Name as "Geor" (Geor?)ecr. l'inf.

Published on October 20, 2013 20:20