Geof Huth's Blog, page 7

April 14, 2013

Recreation of My Childhood

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (Closed) (8-9 April 2013)I wonder sometimes if I am truly a poet--not because of the quality of my poetry, or the recent infrequency of my creation of it, but because I am so interested in the multisensory, in art that presents itself to the world through all senses, that I have now begun to create works that are not poems even by my broad definition, even though I want to designate them such.

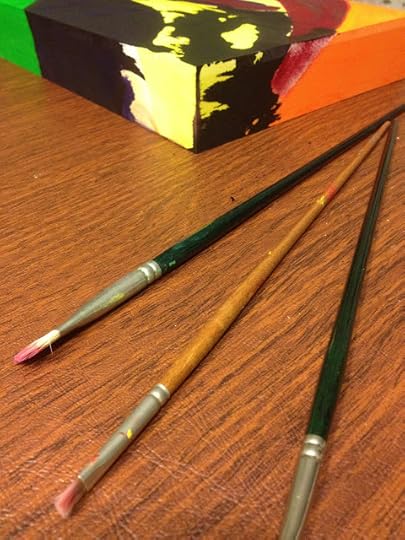

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (Closed) (8-9 April 2013)I wonder sometimes if I am truly a poet--not because of the quality of my poetry, or the recent infrequency of my creation of it, but because I am so interested in the multisensory, in art that presents itself to the world through all senses, that I have now begun to create works that are not poems even by my broad definition, even though I want to designate them such.This year, so far, my two "major" works ("major" requires quotation marks more often than "minor" does) are not poems. The first was an "inking" (a work "painted" only with ink). I had intended to add text to it, to make it into a poem, but I cannot quite do so. I don't want to ruin the run of the inks upon the wooden canvas, thought the use of ink alone gives it the aura of writing to me. I dream of it as a poem.

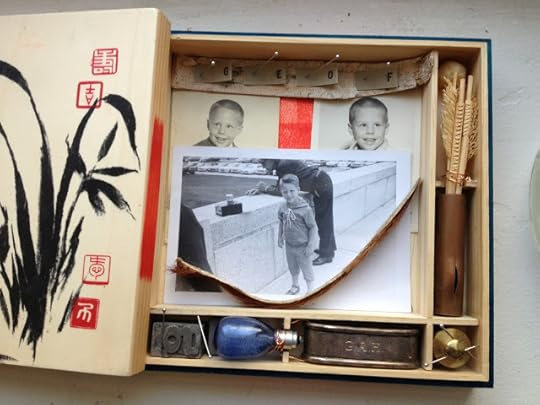

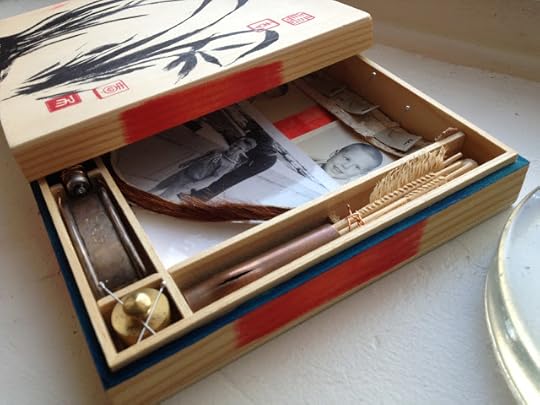

My second work is a wooden box of objects, a box that originally held some sumi-e implements and inks, but which I've changed into a little room. The box has a top, though, so the room and its partitions (or its allied rooms) are invisible. All we can see at this point is the printed images and words on the top, along with a little painted reediness of my own.

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (With Lid Resting on Box) (8-9 April 2013)In making this work, I was trying to remember who I was, as a small child, trying to remember who I was at the age I had flown through the air of my kitchen in northern Virginia propelled by the power of my father's rage alone. I remember only flashes of this story: feeling hungry and taking a handful of Apple Jacks (or another sweetened cereal) from the cupboard and going outside to eat it, being followed a short bit later by my father who dragged me back into the house by my arm, his heaving up my tiny body--I'm almost sure I was four at the time--and throwing me across the kitchen, and this remembered sense of gentle flight, without landing on, without hitting anything. Certainly, I must have run out of the room at this point and up to my bedroom, where I would have closed the doors, turned off any light, buried my head in my pillow and cried until I was overtaking by the onrush of sleep. But certainties are themselves uncertain in the world of memory, which is often no more than rememory, a constant refiltering of memory through the circuits, until nothing by the haze of memory remains, like a thin film of grease atop a cold soup, something so delicate the slightest swish can wipe it away.

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (With Lid Resting on Box) (8-9 April 2013)In making this work, I was trying to remember who I was, as a small child, trying to remember who I was at the age I had flown through the air of my kitchen in northern Virginia propelled by the power of my father's rage alone. I remember only flashes of this story: feeling hungry and taking a handful of Apple Jacks (or another sweetened cereal) from the cupboard and going outside to eat it, being followed a short bit later by my father who dragged me back into the house by my arm, his heaving up my tiny body--I'm almost sure I was four at the time--and throwing me across the kitchen, and this remembered sense of gentle flight, without landing on, without hitting anything. Certainly, I must have run out of the room at this point and up to my bedroom, where I would have closed the doors, turned off any light, buried my head in my pillow and cried until I was overtaking by the onrush of sleep. But certainties are themselves uncertain in the world of memory, which is often no more than rememory, a constant refiltering of memory through the circuits, until nothing by the haze of memory remains, like a thin film of grease atop a cold soup, something so delicate the slightest swish can wipe it away. Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (Open) (8-9 April 2013)But things hold on--memories, sure, in their own way, but also actual things, objects that hold and emit meaning, that reanimate and remit memory, all that is left as each memory, large and small, is released from the body at the knifepoint of death. And meaning can be made and extended by bringing objects together, especially objects filled with one's hermetic meanings (though such meanings are inaccessible to others, they hold on most firmly for us). So I see this little box as a kind of writing, a kind of meaningmaking almost devoid of words, but not quite devoid of them: the characters I must identify are those that come together to make a visible word.

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (Open) (8-9 April 2013)But things hold on--memories, sure, in their own way, but also actual things, objects that hold and emit meaning, that reanimate and remit memory, all that is left as each memory, large and small, is released from the body at the knifepoint of death. And meaning can be made and extended by bringing objects together, especially objects filled with one's hermetic meanings (though such meanings are inaccessible to others, they hold on most firmly for us). So I see this little box as a kind of writing, a kind of meaningmaking almost devoid of words, but not quite devoid of them: the characters I must identify are those that come together to make a visible word.So it is that this box holds memories of mine, even as it breaks the rules of my life, which are many, but in this case they are rules of an archival nature: 1. do not destroy original order, 2. hew closely to the principle of provenance, 3. do not do anything to a record that you cannot reverse. And, to some degree, I see every object in this box as a record.

Original order requires that the archivist maintain records in the order received because that order is the order the creator held them in, that order gives sense to the creator's method of proceeding through life, that order gives meaning that the breaking of the order can never return. Of course, the principle of original order is most often honored in its breach. In this case, I have broken original order in two ways: In the first, I've removed photographs from my 125-year-or-better collection of family photographs to use them in this sculpture, for it is sculptural, and the largest photo is unique and without a surviving negative with which to recreate it. In the second case, I've removed the piece of metal type, the g, from a series that spells out the general name of me, then my wife, and finally my two children, in the order of their births (in the order of all of our births, actually): gnet, which is usually GNET, which is pronounced at least three different ways. In one of its pronunciations, the G is silent, so maybe its loss is the slightest, but now I have left on my bookshelf only "net," a better word, maybe, and a semordnilap, so it might mean ten nets, the better for fishing with, or the tenets of a family.

I am not so sure I have broken the rules of provenance here, but let me explain why I think I have. Provenance (pronounced PRO-vih-nahnss, with a nasalized a, in the parlance of archivists) is related to original order. Provenance requires an archivist to honor the different sources of records, never mixing records of one source with those of another. When such an act is committed, the result is an artificial collection, rather than a set of records, thus the recordness of the records themselves is disturbed, and the records mean less, or at least differently, out of this context. These objects (as records or not) all come from me, all come from a place within my control, all have entered my life in some personal way, but they come from different points of my life, which breaks provenance from my point of view because they were collected and created, received and made, in different contexts of my life, when the only context here is the context of my life in Virginia, from 1963 until 1965, when I was three to five years old. This is the focus of the story of this box.

If I were a good archivist, or a conservator or preservationist, I would never have pasted these photographs in this box the way I did, with the usual glue I use to make collages. I would have found some Japanese wheat paste to affix the photographs to the inside bottom of this box. Because a little water would easily lift the photographs off the wood. But I felt compelled to finish this object quickly, so I didn't wait to do something I could not reverse.

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (Looking into its Darkness) (8-9 April 2013)The box looks back into darkness for me; it is the dark mirror of a small boy, so it includes mostly objects from my early life, but all are not such. And it is filled with meanings no-one might understand, until I tell them to you now. The red ink painted on each of the four edges of the box symbolizes blood, which symbolizes pain, but they are also lips, my big red lips, the closed and silent lips of this box until I raise the lid off it and each pair of lips speaks. The box speaks to us from all four sides: west, east, north, south. The other lips of the box, the two opposing lips that hold the box together are painted--where they kiss, where the lid of the box rests upon the box itself--in blue, because blue is my favorite color, and the color of the sky (a kind of freedom) and the color of the many seas I have lived beside (and which themselves suggest danger and death more than life to me).

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (Looking into its Darkness) (8-9 April 2013)The box looks back into darkness for me; it is the dark mirror of a small boy, so it includes mostly objects from my early life, but all are not such. And it is filled with meanings no-one might understand, until I tell them to you now. The red ink painted on each of the four edges of the box symbolizes blood, which symbolizes pain, but they are also lips, my big red lips, the closed and silent lips of this box until I raise the lid off it and each pair of lips speaks. The box speaks to us from all four sides: west, east, north, south. The other lips of the box, the two opposing lips that hold the box together are painted--where they kiss, where the lid of the box rests upon the box itself--in blue, because blue is my favorite color, and the color of the sky (a kind of freedom) and the color of the many seas I have lived beside (and which themselves suggest danger and death more than life to me).The box itself is divided into five parts, and five is the magic number of my life: I was born in the fifth month on its twenty-fifth day (5 * 5) in a year divisible by five. I have five brothers and sisters, five fingers on each hand, five toes on every foot, twenty-five teeth in my mouth. The accident of these facts and the fact of the five of the box are intentional. The aleatoric is the most intentional way to create a thing.

The top tier of the box is divided into two compartments. The largest compartment is the focus of the story. It contains three pictures of myself, each at a different age: 3, 4, and barely 5. By the time I was three, I had one sibling. By the time I turned five, I had two, with a third arriving only two months later. Because of this, there are no pictures of me alone at this age, except for studio pictures. Every surviving picture my family took of me at this age included one or more other people in there. I had not realized this before, but it is only fair: I was the first born, so I was photographed alone the most of any of us, so my parents took solo pictures of my other siblings as they stopped taking such of me.

This made it difficult for me to find the bottom photograph, a photograph where I am the subject of the photo, even though my paternal grandfather is an accidental subject of the photograph as well. This is my favorite picture of myself, taken at a time before I was the self I am now, one of an adorable little child, one who seems happy.

Inside this compartment is a piece of birch, which represents my childhood interest in nature (I was always in the woods), but which also represents my later writing, which has a strong and strange connection to birch, one made stronger by a fortnight in Finland years ago. This compartment also holds a small piece of animal hide, probably cow, covered in light fur, and that represents both my childhood love of animals (I was always collecting them, keeping them, caring for them, freeing them) and my love of reading (I used this for years as a bookmark, and took it out of a book for this use). This strip of cowhide is the only unanchored object in the box.

The slip of birch is held down with small pins through the letters of my name. Pins pierce skin and cause pain; they draw blood from under the skin, and the red shows through at the bottom of the box.

In the second of this tier's compartments are four decorative handcarved Portuguese toothpicks from my years in Portugal. They represent both my three siblings and I (the most their was of us through my year of being six years old), as well as my constant travel. They are held in place with a bit of copper wire, through which electricity flows, and they rest inside a bit of copper pipe, through which water (like blood through a vein) flows, but one that burst in my house one cold winter from years ago. Together the burst pipe, burst vein of the heart, and these toothpicks represent a quiver with its arrows, the constant hunt of life, both to kill and to find love. Above the toothpicks is a ball of beeswax I made only last year. It represents my constant interest in scent, but also in marbles, mostly because I lost so many of the marbles of my grandfather (pictured) in games of marbles I played in Canada. Marbles represent loss to me. I was no good at marbles.

In the bottom row, there are three tiers, much simpler to discuss. In the first compartment is that aforementioned g of my first name. Next to it is a metal pencil sharpener under a blue flashbulb of a 127 film camera, the kind of camera my parents sometimes use (though in none of these photographs). The bulb represents its time, the taking of photographs of my young being, a flash of understanding, even blueness. Beneath it, the pencil sharpener represents my interest in writing and (to some degree) drawing.

In the next opening is one object: a silver napkin holder given to me shortly after my birth and inscribed with my initials: G.A.H. This is held in place, along with the flashbulb, with a bit of copper wire.

In the next is a weight from a scale, a precise measurement, but chosen only for being a weight (weighty, weightiness, the heaviness of waiting). It is held in place with two pins, just as the g is.

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (In Situ on Dresser with Tie and Acorn) (8-9 April 2013)

Geof Huth, "Recreation of My Childhood" (In Situ on Dresser with Tie and Acorn) (8-9 April 2013)When I finished my object sculpture--which still requires some repairs and modification, mostly to keep everything in place--I placed it on my dresser, on display for me every day. Before it rests a coiled woolen tie my mother knitted for my father when I was about four, and a single tiny acorn above it. I can no longer remember where I found this acorn, but I keep thinking it was California, the place of my birth.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 14, 2013 11:30

April 12, 2013

The Multiple Varieties of ART

Peter Ciccariello's Visual Poetry (from iARTistas # 5)

Peter Ciccariello's Visual Poetry (from iARTistas # 5)Didi Menendez has done it again. She has put together a remarkable magazine of art, some of it poetic, some of it visual poetry, and most of it visual artistic, and she's delivered it (this time) in so many formats that the mind reels. There are gorgeous visual poems, paintings, and photographs in this issue, all ready for your delectation.

Here are some of the venues for your feasting:

iPad Edition

This the the primary edition of the publication, and this is where the vision of the magazine comes through. The cover is animated and audible. Visual poems and followed by tiny verbo-visual movies of the poems. The voices of the poets read the poetry. If you have an iPad, download this free edition from iTunes via the link above.

Digital Edition

The digital edition is a flat online edition, designed as a paper edition. You can scroll through it, and zoom in, but it has none of the movement, visual and aural, of the iPad edition. This edition is free to anyone, and one click gets you watching it.

Print Edition

The print edition is the only one that costs. It's $15 dollars, payable through PayPal. I've just ordered my copy, so I can't say much about it, but I've seen Didi's other print publications, and they're all beautiful, and in full color.

Vimeo "Edition"

This is not really an edition, but this gives you a means to see the videos that appear in the iPad edition.

Submissions

One final point: The editors of iARTistas are reading for the May issue, and I do need some more visual poems for that edition. Follow the link to information on submissions, and consider sending me a stack of related visual poems for iPo (the section of iARTistas dedicated to visual poetry).

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 12, 2013 18:30

April 1, 2013

The Only National Poetry Month Worth Its Salt (Even Stuffed in a Burlap Sack) is .ca

Gary Barwin's Visual poem of an unknown title, but possibly consisting of but a single letter

Gary Barwin's Visual poem of an unknown title, but possibly consisting of but a single letterEliot, T.S. (whose initials we must imagine stood for Tough Shit, [Ezra]), told us that April is the--and this is his spelling, having given up his Missourian orthoepy--cruellest month. He was, of course, opening a great poem with this as he was opening spring to us, just as Geoffrey Chaucer (whose namesake I intentionally am) began his own tale of pilgrims' travels to Canterbury. It was at the opening of muddy spring, on the first day of April, that poetry began, or begins, and we were given "National" Poetry Month (the nation in flux, depending on where one stood), because of this poem, because of the wasteland Eliot had created.

Where was I?

Ah, yes, this is National Poetry Month, which I don't care much for. During April Knopf decides to send me a poem a day, in celebration of the month, but also in order to sell us some of the poetry books it publishes, but I am mostly amazed at how much I hate the poems they show me. I read them, but I approach them with dread, experience them as dread materialized, and remember them as the slow seeping away of dread.

Dread.

(knopft)

So there must be other poetry months somehow occurring simultaneously, as if in parallel universes. Yes, there are. First, I promote the most portable of poetries during this month: pwoermds, or one-word poems. And there are dozens of people who practice this unmaligned form of poetry. (Sure, you were expecting "maligned," but maligning requires knowledge of, and I haven't quite cracked the publishing towers of Manhattan. How International Poetry Writing Month could not break such towers, I cannot understand, but that this is the case I do know.

(knopft)

Even better is National Poetry Month (.ca) run by Amanda Earl, proprietress of AngelHousePress, where the poetry is different and strange, and interesting, and where this month of April will be celebrating the month, this year, with nothing but visual poetry. Here's Amanda's announcement:

AngelHousePress presents NationalPoetryMonth.ca, a celebration of poetic form of all kinds and an homage to those poets who try to extend the definition of poetry. This year's edition, which marks our fifth anniversary, is a tribute to the Last Vispo, an anthology of visual poetry edited by Nico Vassilakis and Crag Hill and published by Fantagraphics in 2012. The site contains visual poetry, asemic writing, collage, concrete poetry and other forms of whimsy by artists from Australia, Canada, the USA, Finland, Hungary, Italy, and Sweden. Each day in April a different visual poem will be shown. AngelHousePress thanks all who participated and sent work for consideration and wishes the month had at least forty five days in order to showcase all the great poetry we received.

Starting April 1, please visit NationalPoetryMonth.ca for a different visual poem every day.It should prove to be a great month of poetry if my friend Gary Barwin's opening bpNicholesque poem of the two descending legs of one fine capital letter are any indication. Follow along. Breathe poetry. Don't let poetry breathe you.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on April 01, 2013 20:07

March 31, 2013

April is the Pwoermdest Month

Geof Huth, "ffjordffloess"

Geof Huth, "ffjordffloess"Once again, though a bit late in the running of time, I announce the onset of International Pwoermd Writing Month VI, which begins tomorrow. The challenge of this event is for participants to write at least one pwoermd a day for each day of April.

For those who may not know, a pwoermd is nothing more than a single word presented as a poem. These have not titles except for themselves, and they are often portmanteaux but they don't have to be. Pwoermds can be simply textual, or they can be visual. The one I present above seems to be both merely textual and visio-textual at the same time, since it is merely a representation of the word in type, but also since the expansive use of ligatures, an even an ancient long s, bring great attention to its visual form.

If you intend on participating in InterNaPwoWriMo6 (the official abbreviation of the full name), just drop me a note here, on email, via Facebook, any way I can reach you, only so I can keep track of your participation. At this point, I'll count myself and Mark Young as the participants, since I'm running the event, and since Mark is always writing a pwoermd a day!

And, this year, mIEKAL aND plans to put out a book through Xexoxial Editions of all the pwoermds included in this year's springtime celebration of the pwoermd, so get involved.

Good luck with your creations.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 31, 2013 05:43

March 27, 2013

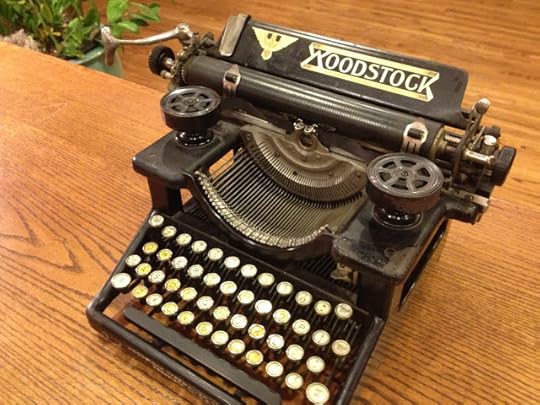

Once, a Chicago Typewriter I Did Not Type Upon

I have been a bit lazy, not tired, but almost into it, like a slip into warmth, have become more of a watcher than a wreader. The words could come--that is no problem--were I to have a stronger desire. Instead, I have a paradesire, a cripple's desire to walk but to not-want the effort required of it.

Writing is a writhing of the spirit, a need to make rather than a need to make sense. Production over argument, heart over lung, a means of breathing forth so that a breath inward may at some point be possible. It allows for life.

But only for the writer, whose only true reader is visible, full-face, only in a mirror, though that mirror might be of glass, or rocking water, or soul. A writer's winter is a blank, whiteness, a sheet, a screen, a continuing cold, as in this winter that continues, holds on, fingernails into our skin so that it cannot fall off of us.

Once, I was a writer and strong of word, willing to wrest the word for the rightness of it. Now, I am a watcher. With every letter I see before me on the screen, a bit of light falls away. But there's not enough pixel ink to blacken out the screen. I no longer have the words to keep the snow blindness away. I am almost blind.

Yet there are words. Listen to them prick your skin and crawl into you. Soon, you will be a writer, too.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on March 27, 2013 19:02

February 19, 2013

What I Once Will Be

Geof Huth, A Draft of an Inking (19 February 2013)

Geof Huth, A Draft of an Inking (19 February 2013) I have not been productive of late. At least not in any way I'd like to be. The act of creating has become not difficult but rare. It's not that I cannot make anything. It is that I have no will to make. Only desire. And, as every melodrama teaches us, desire is what destroys us. Desire without the calming force of fulfillment causes tension even, so it seems, in a person almost devoid of productive drive.

So tonight I forced myself to work on a poem, a visual poem, the idea for which has been rattling inside my head for a couple of months but the outlines of which are still vague. I learn what I want to create through the process of creation. No amount of pre-planning can prepare me for whatever will happen.

I unwrapped a canvas tonight, a basswood canvas attached to a deep pine frame. My idea here was to paint on the canvas with ink. The photograph above might seem to be of a painting, but it is an inking. Since I'm a writer more than an artist, I draw with ink, I paint with ink. As I began painting this, I had no idea what I was trying to do, but I found myself making fields of color vaguely in the manner of Sonia Delaunay in her visual poetic collaboration with Blaise Cendrars entitled "La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France."

Since I had, at that point, an idea of what I was doing, I spilled a large quantity of ink over the beautiful swath of yellow I had painting onto the board, and now I have to rethink my plans. But I'm enjoying the imperfections of the spill. I just remain unsure how I'm going to add text: pen, rubberstamp, collage, gouging, maybe all of them?

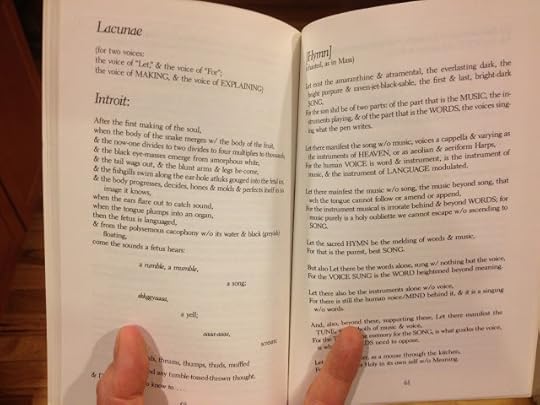

Also today, I received what I might consider my contributor's copy of a journal publishing one of my poems back in 1988: Studia Mystica, Volume XI, Number 4. I never received my copy because I'd moved from Syracuse before it arrived, and after (it seems) my mail was no longer being forwarded. I've looked for this for years but never found anything. Until last week, when I found a copy online and bought it right away. What this allowed me was the opportunity to read I poem I'd written a quarter of a century ago, a long poem that I'd never finished, one that was supposed to include a number of handdrawn visual poems within it.

As I read this over again tonight, I saw all the influences I forgot were there (Gerard Manley Hopkins, Vachel Lindsay, the Catholic Mass), but I didn't really feel the full effect of the influence I'd remembered (Christopher Smart's Jubilate Agno). Yet there was something else in this poem: me. I could see my over-concern for sound, my interest in the visual, my interest in language as a physical product of work, something palpable. I could still write some of these strange twisted lines today. I have remained, to a great degree, the same poet, just older, maybe richer in some ways.

I wrote these lines, this poem, in graduate school at Syracuse University, in the class for us handful of poets. As I looked back at them tonight, I realized how different I was from the rest of them, two of them quite fine poets. Most of them told stories of living; I played with language. My game was language as music and language as visual art. I was more interested in drama than narrative, in cacophony than syntax.

I loved syntax. I just wasn't a vassal of it. My poetry has always been concerned with thepalpable modification of the physical stuff of language. Even back when I was vaguely conservative and reserved in my definition of poetry, I was working somewhere separate from my colleagues, on a different continent, but still in the same hemisphere.

This was years before I had painted with ink for so long that I could find myself at the end of an evening with a wooden canvas covered with the unlettered shapes of ink and could think of that fully visual creation as simply a draft of a poem I had not yet imaged the shape of.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 19, 2013 19:47

February 12, 2013

He Noted, Head Bowed, That the Sentence Was Too Long to Be Fair

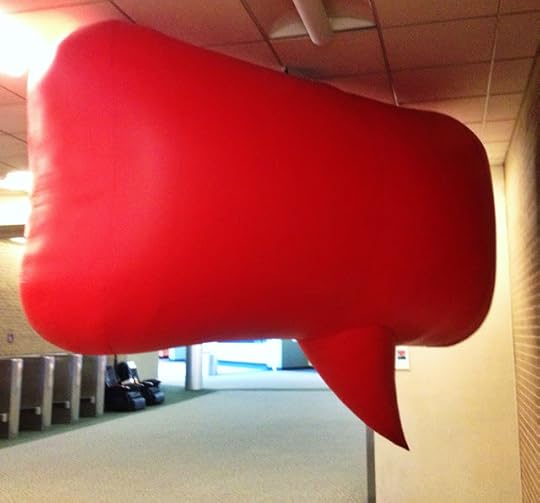

"Blood-Red Balloon of Speech" (23 January 2013)

"Blood-Red Balloon of Speech" (23 January 2013)A colleague of mine who is also a poet (a poet and an archivist and records manager--so one of those few who is combined into one as I am) wrote to me last week about the sentence, and she said,

Paragraphs are largely arbitrary, from my experience. Not so a hovered-over, coddled, adored sentence.

It is the individual sentence rhythms that get the momentum breathing, going!

Once she sent me this message, I wrote back, noting that it made me laugh, and adding

I think it's the "hovered-over, coddled, adored [that caused my laugher.." Rhythms go through paragraphs, and sentences are as arbitrary as paragraphs. Listen sometime to the unsentenceness of actual speech.My point is manifold. Everything about language is arbitrary to a great degree. Certain words may be built from certain concrete sonic facts of the world: the "mm" that often accompanies the word for "mother" in many languages, or the abounding onomatopoetic words. But even these are fragmentary in terms of significance. Certainly, that opening "mm" in "mother" and "madre" and "mère" may come out of the sound of a baby's mouth sucking upon the nipple of its own mother, but that is just an artifact of sound changed dramatically in each of these words. And compare onomatopoetic words for the same sound (say, the crow of a cock) across languages, and you will be assaulted by a cacophony of different hearings, because there is little hope for the human tongue to represent every sound of the world accurate, even those emanating from our fellow beasts of flesh and blood.

So, yes, the paragraph is arbitrary, but so is the sentence, and the word, and the phonemes within the word, and the connections we intimate between those phonemes and those arbitrary shapes we call letters.

I wondered, though, what magical thinking caused my colleague to assume that the sentence was not as arbitrary as the sentence. For instance, what about these two sentences I've just written?

Certain words may be built from certain concrete sonic facts of the world: the "mm" that often accompanies the word for "mother" in many languages, or the abounding onomatopoetic words. But even these are fragmentary in terms of significance.

Why is that second sentence separate from the first? Why didn't I just keep them as one? Would anyone have heard these two sentences as two if I had spoken them aloud, or would they have hear them as three? Is the sentence beginning with "But" separate so that it can stress the caveat? Or is it separate because the visual syntax of the first sentence is broken by the colon, and I felt the flow of the written sentence could not be maintained with a simple comma before the "But," so I went for a more forceful caesura? How many sentences are actually there?

I think about such things, because I think about language, and I read constantly, and I listen to how people speak. Not everyone does. Not everyone recognizes how natural speech, no matter how formalized, is never as constrained as writing, or how writing does not replicate speech but manages it, controls it, shackles it, always hungry to be clear and clean.

If you transcribe a sentence set loose in the air sometime, you might hear something that I could transcribe in this manner:

I don't--really, I don't--care about whatever it is that you think, or you think you think--never have since that time you--well, you know all about it, so why should I tell you? after all you've done, and it seems just so, uh, well, who knows? stupid, maybe, or juvenile, it is that you've done that it just doesn't seem worth it any--you know what I mean, it's so stupid to keep talking, so stupid to try, like we can ever make sense to each other--and it's always been this way, something like a weight over us, something you couldn't stop, something I couldn't take or move or give away or anything, because you're just so stupid, have always been, will always be, so that's it--that's why we're done.

I'd say that's a sentence, and that it is also a paragraph, the latter merely because of it's length. But I could carve it into many sentences, and make the argument that it is a cluster of sentences focused on a single point. But I won't. When that clump of words hangs in the air, when it streams out of someone's mouth, it is a single sentences, a huge string of words, a concatenation of sense that is messy and ugly and totally understandable.

We could sculpt a fine sentence out of this wandering set of words, but why would we? Just let it live in the air where it belongs, hear the sting of it, and move on.

Still, a rhythm goes through this sentence, an arhythm maybe, for it is a set of words, so it is held together by meaning and rhythm and the pure sound of the phonemes, and it is a meaningless set of verbal symbols, except that someone taught us the key.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 12, 2013 20:24

January 27, 2013

One Say

Last time there was a US presidential inauguration, we had an inaugural poem I thought was execrable, but Richard Blanco's "One Day," performed this year, was much much worse. Harkening back to Carl Sandburg, he gave us a confetti-like story of Americans working across the country and through sunlight and hard work. It was, I suppose, a populist poems, and one filled with enough egregious lines of queasy faux emotion to make me sick. So I took his poem and fashioned a new poem by lifting a few words from his, excising all the lard, making new words, and writing a fragmented little poem of my own. Still, I think it's better than Blanco's.

I feel a bit sad about being so openly outraged by the terribleness of this poem--after all, I assume it is impossible to have an inaugural poem that most people don't hate--but this poem seemed to be telling us that poetry was boring and useless and an insult to a readers sense of intelligent honor. So I'll leave my unhappy words intact.

And I'll leave my poem here:

sun rose over, spreading —a simple gestureslight and windowed—a million mirrorsbroken into light of dayand colors,the process for these,words, vital,and we move through waves,these heights,vocabulary of lossand breathing,warm into the cold day forth,every thing rootedand rutting for us, and from, the work we do with bodyand brain of muscle,—dust and sweat and mingle,songbird flight,an every languagewound into the wind thruus, these soundsblistered by lip and tongue,with our hands,upon our selves and wounds,the jut of tower—thewinter weathering usdownward but forward,in whatever praisecould plummy dusk makeof these small acts,the pulse, then the drumof stars, the nameless many,all awaiting what we must make.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 27, 2013 20:21

January 14, 2013

lightly.

lightly.

there is a fall to it, quite

it semes

(my intent was out)

filtered not favored,

yet its taste

[cold in a warm way . . .

presense

we came here to

, as well

the whole ocean of it

supine.

prickly in temperament tho not heat

every thing segmented:

as to see

my dear Amnesia, lost as tea–

the fold of the papered leaf

we grow weary waiting

[yet sunlight]

could be it was remembered

so subtle, almost white

he took it;

valiant they thought

the moon covered in dew

centuries of sweat

redness receding (

held)

the slightest reason for

he asked for it

an apple

pouring portions for each

she taught him

after the fall

before it had sprung

a reaching

tenderless

fork & torque

the color of blood, not taste of

dried it

soaked by

inches but that was enough

around that time like the face of a clock

hand for hand

swivel at the joint

the head turned

alive

the thought before slipping

fractures

& all at once

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 14, 2013 18:59

January 9, 2013

The Seeming Semiobject, More than Seen

Geof Huth, "In Their Collected Beauty # 12: ROCK GARDEN PHARMACY" (2012)

Geof Huth, "In Their Collected Beauty # 12: ROCK GARDEN PHARMACY" (2012)Every poem is hermetic. Every response to a poem is a personal. We view the world through two holes out from the head we think within. We hear that world through two holes punctured through the sides of our holes, but again from the inside. We live inside our own respective skin, and there is the color of our own thoughts upon everything we encounter.

I think of how I make a poem: I make it for myself to see, because I don't know how anyone else's eyes work. Every poem I make is a reflection of myself, and in most of them there are phrases, connections, even individual words that I expect no-one to comprehend except for myself.

The hero of this story is Hermesis.

A thought there is that universality is required of a great poem. But maybe it's the opposite. Maybe nothing is universal. Maybe only the multitudinous differences of us all are the only thing nearly universal.

So I think of a little poem of mine that lives within the skin of a bottle and looks out through that transparent skin with my eyes, and yet also into my eyes. It is a poem in a series of poems created out of objects I'd collected over the decades of my life, so each object holds meaning to me that it won't to others.

I ate the salt and pepper that once filled this jar, I know where the pebbles in this jar are from, I found the prescription bottles inside this jar behind a wall on the third floor of my house, and the information typed onto the labels for these bottles was typed with the same semi-cursive typewriter font that my maternal grandmother used to write letters to us.

Meaning inhabits things just as it inhabits humans.

There's something else about these object poems of mine, which I often call semiobjects, because they are semiotic objects, because they are half object and half not. I realized that many of my object poems (though not so much this one) don't exhibit well, because I didn't intend them for exhibition. I didn't realize this until I'd seen my pieces on exhibit, but I made all of my semiobjects to be held, manipulated, touched.

I am a poet of the body, so I want these semiobjects to be experienced as much by the body as is possible. The become alive if they are treated also as bodies, bodies of thought, bodies of objects, bodies in motion. So these poems are made to move, designed to change by your looking at them. The poem are made to be felt, seen, heard, even smelled, though none is quite designed to be tasted.

These are poems of the senses and the word because we are beings of senses and the word.

Someday, I might get these right, but if I rattle this poem a little I can hear, though still too faintly, the sound of an ocean unfurling itself over a layer of pebbles in many colors.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on January 09, 2013 20:55