He Noted, Head Bowed, That the Sentence Was Too Long to Be Fair

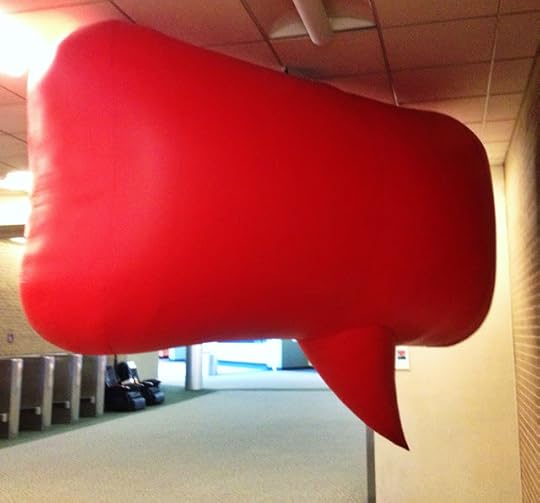

"Blood-Red Balloon of Speech" (23 January 2013)

"Blood-Red Balloon of Speech" (23 January 2013)A colleague of mine who is also a poet (a poet and an archivist and records manager--so one of those few who is combined into one as I am) wrote to me last week about the sentence, and she said,

Paragraphs are largely arbitrary, from my experience. Not so a hovered-over, coddled, adored sentence.

It is the individual sentence rhythms that get the momentum breathing, going!

Once she sent me this message, I wrote back, noting that it made me laugh, and adding

I think it's the "hovered-over, coddled, adored [that caused my laugher.." Rhythms go through paragraphs, and sentences are as arbitrary as paragraphs. Listen sometime to the unsentenceness of actual speech.My point is manifold. Everything about language is arbitrary to a great degree. Certain words may be built from certain concrete sonic facts of the world: the "mm" that often accompanies the word for "mother" in many languages, or the abounding onomatopoetic words. But even these are fragmentary in terms of significance. Certainly, that opening "mm" in "mother" and "madre" and "mère" may come out of the sound of a baby's mouth sucking upon the nipple of its own mother, but that is just an artifact of sound changed dramatically in each of these words. And compare onomatopoetic words for the same sound (say, the crow of a cock) across languages, and you will be assaulted by a cacophony of different hearings, because there is little hope for the human tongue to represent every sound of the world accurate, even those emanating from our fellow beasts of flesh and blood.

So, yes, the paragraph is arbitrary, but so is the sentence, and the word, and the phonemes within the word, and the connections we intimate between those phonemes and those arbitrary shapes we call letters.

I wondered, though, what magical thinking caused my colleague to assume that the sentence was not as arbitrary as the sentence. For instance, what about these two sentences I've just written?

Certain words may be built from certain concrete sonic facts of the world: the "mm" that often accompanies the word for "mother" in many languages, or the abounding onomatopoetic words. But even these are fragmentary in terms of significance.

Why is that second sentence separate from the first? Why didn't I just keep them as one? Would anyone have heard these two sentences as two if I had spoken them aloud, or would they have hear them as three? Is the sentence beginning with "But" separate so that it can stress the caveat? Or is it separate because the visual syntax of the first sentence is broken by the colon, and I felt the flow of the written sentence could not be maintained with a simple comma before the "But," so I went for a more forceful caesura? How many sentences are actually there?

I think about such things, because I think about language, and I read constantly, and I listen to how people speak. Not everyone does. Not everyone recognizes how natural speech, no matter how formalized, is never as constrained as writing, or how writing does not replicate speech but manages it, controls it, shackles it, always hungry to be clear and clean.

If you transcribe a sentence set loose in the air sometime, you might hear something that I could transcribe in this manner:

I don't--really, I don't--care about whatever it is that you think, or you think you think--never have since that time you--well, you know all about it, so why should I tell you? after all you've done, and it seems just so, uh, well, who knows? stupid, maybe, or juvenile, it is that you've done that it just doesn't seem worth it any--you know what I mean, it's so stupid to keep talking, so stupid to try, like we can ever make sense to each other--and it's always been this way, something like a weight over us, something you couldn't stop, something I couldn't take or move or give away or anything, because you're just so stupid, have always been, will always be, so that's it--that's why we're done.

I'd say that's a sentence, and that it is also a paragraph, the latter merely because of it's length. But I could carve it into many sentences, and make the argument that it is a cluster of sentences focused on a single point. But I won't. When that clump of words hangs in the air, when it streams out of someone's mouth, it is a single sentences, a huge string of words, a concatenation of sense that is messy and ugly and totally understandable.

We could sculpt a fine sentence out of this wandering set of words, but why would we? Just let it live in the air where it belongs, hear the sting of it, and move on.

Still, a rhythm goes through this sentence, an arhythm maybe, for it is a set of words, so it is held together by meaning and rhythm and the pure sound of the phonemes, and it is a meaningless set of verbal symbols, except that someone taught us the key.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 12, 2013 20:24

No comments have been added yet.