If It Were Raining, That Would Be the Night for It

Riding a New York City subway train today, I noticed to my right a poem on the wall, part of the Poetry in Motion program of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. I have nothing against this project, but neither do I often find a poem on one of these square posters that is worth remembering. Yet I always take the time to read these poems when my eyes rest upon them.

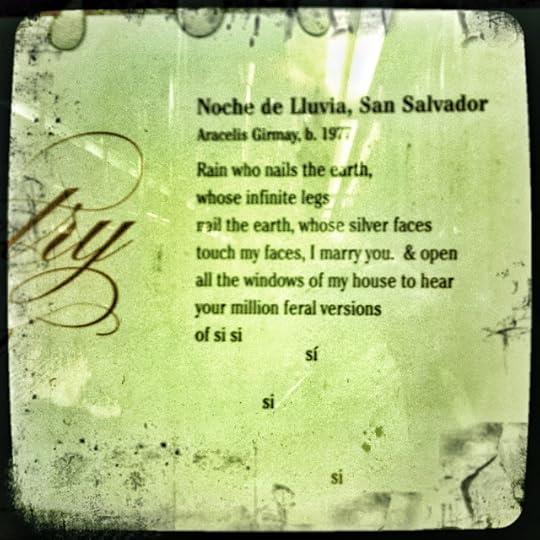

This time, I noted that the poem's title was in Spanish ("Noche de Lluvia, San Salvador" or "Night of Rain, San Salvador") and that the poet's name was Aracelis Girmay. I assumed the poet was some Salvadorean poet who had been translated into English, so I wondered why the title wasn't translated, and I wondered, even more so, why the poem ended with five words in Spanish.

I did like the opening pair of words to this poem ("Rain who"), which personified the rain, but grammatically instead of directly. Unfortunately, the poem dived next into other more obvious instances of personification, diminishing the initial genius I found within it. Still, I thought the poem vaguely acceptable, and I liked the idea of raindrops being defined as the Spanish words "si" and "sí," which do not mean the same thing.

That's what set me wondering: Did the translator believe it impossible to translate these words successfully into English? Was the loss of the essential pun more than the translator could bear to lose? Did the translator believe the poem could work even if most of its readers didn't understand its final lines? even though most readers were likely to interpret both "si" and "sí" as "yes"?

Interestingly, only one of the five words ending this poem means "yes." The others mean "if." So the poem is not so much affirming as questioning or positing. This isn't Molly Bloom at the end of Ulysses. This poem ends with the words

your million feral versions

of if if

yes

if

if

And, maybe (I thought to myself), that adequately represents the Spanish original, since both of these words are monosyllabic and sibilant. Anyway, comprehension was more important than punning. In Spanish, the poem's true language, the poem would function as Girmay intended it to.

After I returned to my small set of windows looking out at the world, I changed my mind. And I did this because I looked up Aracelis Girmay and discovered that she was an American, so she had to have decided to use Spanish in her poem, to open it with a title in Spanish and end it with puns in Spanish. Thus, the poem worked bilingually and should remain that way.

Still, it was a poem written for anglophones, but one with a slight barrier to full understand, so why did the MTA decide this poem made sense for their purposes? Did the MTA decide it wanted to challenge its audience? Doubtful, I thought. I concluded that it was a poem short enough for this program.

Just a few lines, just a few lines is all we have time for as we sit or stand, with nothing to do, while we course through the dark subterranean veins of New York.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on May 20, 2012 20:43

No comments have been added yet.