In the Beautiful House of the Written Hand

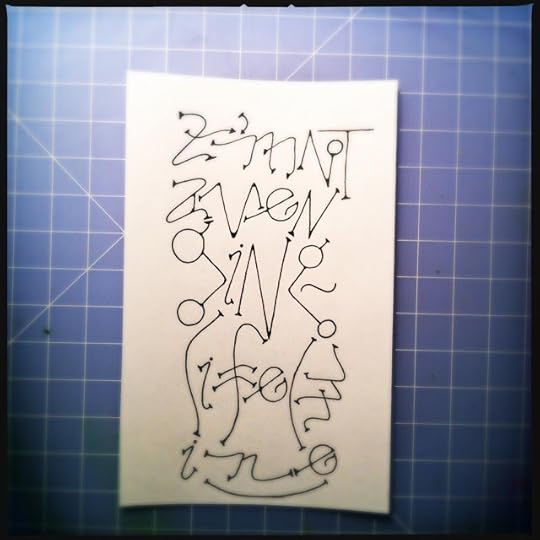

Geof Huth, "2'mNoT" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, "2'mNoT" (15 February 2012)What do you think about the endangered status of hand-writing in some schools' curricula? What effect do you think it has on language art, or language, or art?

(Question received from Jeremy C. Casabella, 15 February 2012)

The hand is a tool, a tooler, a talent.

We say an artist has a good eye, and certainly the eye directs the hand, but the hand must be steady, muscled as it must be, flexible yet sturdy. An artist needs a good hand, which could be either left or right. Or both.

And "hand" may be end of an arm, applause, aid and succor, or the singular shape of a person's handwriting.

Handwriting is how characters acquire character.

Just a few thoughts, scattered about, in answer to a question Jeremy C. Casabella sent me yesterday, but early yesterday, so early that I awoke to it, via my phone, before even rising from bed, a rising I had no desire to manifest. Through the day, while dealing with many other questions from folks about the issues I handle (appraisal and retention of records, travel rules, personnel and their performance, and even questions of such a personal nature that I might not even want to mention I had been asked them), I considered Jeremy's question, wondering forth, in particular, my own connection to handwriting, my sincere dependence on it, as artistic expression, as literary gift, as lifeblood of a life so much made up of the tapping of keys into words.

Still, there is music there somehow.

After passing through depressing manifestations of the self as realized being (whatever the DEFFIL that means), I ended the day, almost that full half of it, with a single meeting, conducted via bellowing phone call from the bulbous belly of my grey and insistent companion, about the national coordination of disaster response for cultural materials. (Such are the rough outlines of my working life, one I find endlessly fascinating, even though I am human and can always imagine an end.) During this teleconference, I began to draw fidgetglyphs that focused on the idea of handwriting. I considered how I wrote out the characters of this Latin alphabet of ours, in all their allographic glory. I examined the value of the the handwritten character.

Truth be told, I seem more interested in the handwritten character of a vehicle for poetry than anyone else. I make a distinction here between the handwritten and the calligraphic. They both might be beautiful writing, but calligraphy (as variously practiced) comes burdened with a different set of assumptions and constraints, many of which I take into account in my use of the handwritten, but none of which accounting turns the tables and changes the balance so that a calligraphic manifestation is evident. (Except when I work directly in the tradition of calligraphy, though that produces calliglyphs instead of fidgetglyphs, and the latter is the better word.)

A fidgetglyph is an extemporaneous dance of the hand, so I do not know the end of it, or even the beginning, when I begin it. I don't not begin with words (and sometimes don't even include them); I begin with shapes that remind me of letters and that may grow into words as my hand explores the visual and semiotic possibilities of those inklings. So the opening character of my fidgetglyph "2'mNoT" may be a numeral 2 or a crossed capital Z or an I. This shows us the power of handwriting to support ambiguity, and ambiguity is the protyle of poetry. We create everything worthwhile out of it.

That little fidgetglyph is more than the sum of its few letters, the words they make in a meandering row into a little sentence. The poem means by being words and letters of a particular shape, which mimic and mirror each other, which form a cohesive but not total symmetrical whole. The gestalt makes it for us. (I exaggerate, believing, as the overwrought creator of the thing, that my extemporaneous creation of the thing allows me insight into how it works, and believing that this carries with it the onus of too many years among the words, the shapes of the words, and the sounds I seem to think those shapes make.)

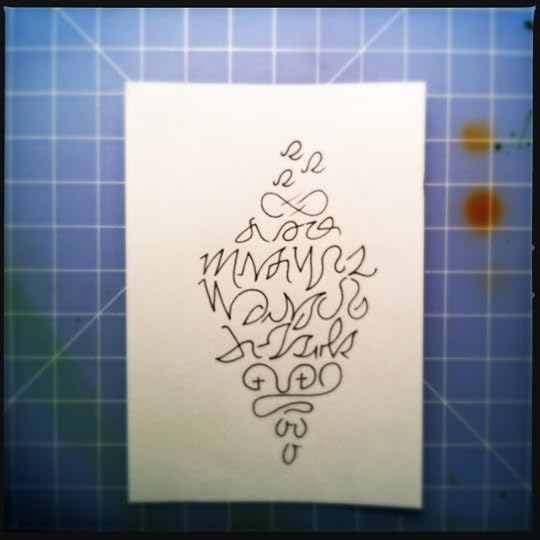

Geof Huth, "R/s" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, "R/s" (15 February 2012)The first fidgetglyph I created yesterday, at the feet of my phone, was a simpler one, wordless, and less successful (though those last two descriptors are not irrevocably tied together in the realm of fidgetglyphing). My experiment here was with ambiguity purely. (As I demonstrated once, years ago, in an old poem forgotten by everyone but myself, I am ambiguilty.)

The three "identical" characters I wrote to represent both majuscule Rs and the minuscule s's that follow them in the recitation of the alphabet. Much of the rest of the fidgetglyph is about the imperfect replication of identical forms, so a line of Ms devolve into W-like forms. Any handwriting is about replicating certain shapes in recognizable forms, but it is also about the ways in which those forms change. For instance, there are often quite distinct characteristics of handwritten letters in their initial, medial, and terminal forms.

This diamond (just about a "lozenge" in early English pattern poetry terminology) is a coalesced examination of these ideas, a practice at written into the ambiguity of it, a poem wordless but larded with the almost instances of words.

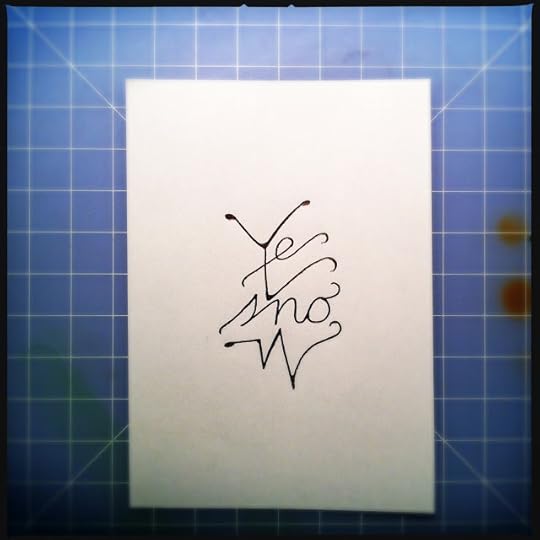

Geof Huth, "Ye" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, "Ye" (15 February 2012)One of the afternoon's latest glyphs was the shortest, but it was also one entirely focused on the cursive hand.

It seems to me that the most beautiful symmetry is, always but in part, asymmetrical, requiring the eye to fix the true and sure symmetry in the mind, but allowing the eye a little revery in the visual dissonance, in the beauty of the imperfect.

So it is that that giant Y, a majestic majuscule, does not perfectly replicate itself, yet, it does, and it echos everything around it: the paraphlike end of the e, shapes that echo down through the terminal flourishes of the o and the W. None of this is accidental; it is the agency of the eye assuming its dominion over the creation of this modest fidgetglyph. (I pause to point out that fidgetglyphs are intentionally modest, their official definition including the requirement that they be "unambitious.")

This is a visual poem, fully visual, embracing its attractiveness to the eye, calling out to that organ of unhearing. Yet the poem is also verbal, intentionally and intensely so. It is a pun, two words strung together into one vocalization, but also a pun, on opposites and on acceptance and desire for. And this vocal element is heightened by its focus on the central phoneme of the five phonemes that make up this poem: the /s/. The sound of that s is drawn out by the s-like flourishes ending the Y and the e that begin the poem. That sound that s, is the sound of snow in the process of being used, not the sound of snow falling, but the sound of skis or snowboards or sleds across the snow, even of the tires of cars rolling through the melting fabric of that fallen snow.

It is the writing, the handwriting, the understanding of how a letter is formed and can be formed and can mean through its various incarnations, that makes this poem work. "Yesnow" is not really a poem at all. It has no exuberance, so there is no way to undercut that happiness with ambiguity or sadness.

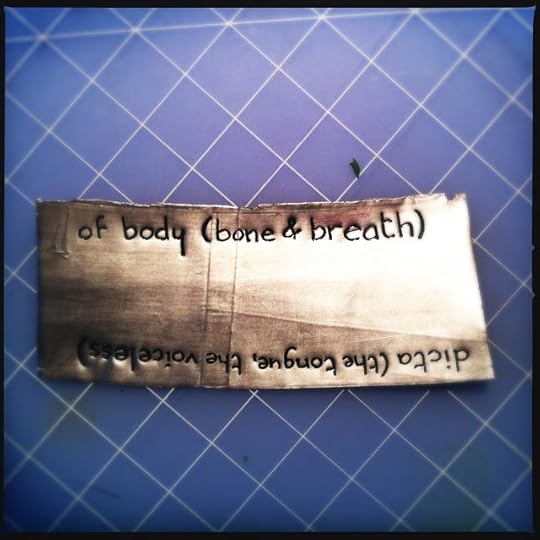

Geof Huth, from "of body (bone & breath)" (15 February 2012)

Geof Huth, from "of body (bone & breath)" (15 February 2012)After returning home from the day's work, I was still involved in handwriting, I was still focused on the meaning of the word as written out by hand. My goal was to finish a poem of mine, but not an ordinary poem, an object poem, but not an ordinary object poem, but a jar poem, a cork-stoppered jar filled with objects in multiplicities and confusions, but this one was unfinished. It was still absent its words.

The day before, which was Valentine's Day, the day of the heart (even for the heartless or heart-broken or for those with hearts that needed to fail but were stopped by knives and saws and an opening up and replacement of parts), I had written a few appropriate words to add to the poems, only two lines, but designed for this poem:

of body (bone & breath)

dicta (the tongue, the voiceless)

I had imagined that I would handwrite these words on slips of paper torn out of sheets of paper, but something else happen. The fumbling hand of Fate intervened. Inside the suit I was wearing, I found the lead band from a wine bottle, a band taken from a bottle of wine drunk at a restaurant sometime in the past, and taken roughly: I had run a key or the tip of a pen, something not . . . as sharp as a knife, up through the lead, leaving behind a wrinkling cut. The lead was lead-grey on the inside but blood red on the outside, so it seemed to me appropriate for this collection of material.

This jar poem, which is part of a longpoem I am now calling In Their Collected Beauty (but which I had only recently been calling Every Poem Ever Written, a more dramatic but less outrageously pretty title), contains my most disturbing of collected items. The most so are a partial human jaw and human teeth collected from a graveyard surrounding a church in Rohrbach-le-Bitche in Alsace, France, the source of my Huths, including my great-great-grandfather Johann Huth who traveled to New Orleans in the 1850s only to die young in that bowl of pestilence, as generations of my ancestors did, young, only 43 years of age. When I visited Alsace (and West Germany and Corsica) on a genealogical trip, in 1985, I ended up in Rohrbach and found the entire graveyard around the church dug up, gravestones toppled and broken, bones and jaws and teeth church up out of and lain upon the earth. It was a shocking discovery, but I collected a number of pieces of the dead from this site: a lower jaw, a palmful of teeth, a partial skull pan, and two porcelain Christs on the cross, both broken from the wrenching open of the graveyard ("cemetery" being too heady a word for such a small collection of graves). When I picked up these pieces of humanity, I realized that they might have been ancestors of mine, that they were likely relatives.

I placed all of these pieces except for the piece of a skull (which was too large for the mouth of the jar) into the jar, and I added to it a number of other items: Quite a few camel's teeth that I had procured while living in Somalia, a few of them drilled at one end so I could fashion them into keychains; the upper jaw of some small rodent; a tiny glass jar, stoppered with the tiniest of corks, and holding a small grey-blue seasnail shell; a small perfume bottle found in my backyard, empty but irisdescent from its life within the chemicals underground in a houseside midden; and a bottle of Chanel No. 22, nearly empty, nearly evaporated, but potent enough that if I open the larger encompassing jar, my nose is met by a smell more redolent that even the death that occupies that glass jar.

So it is that my two lines of poetry complete this poem of objects. This is a poem about the human body, and the bodies of all the small animals surrounding it, a poem about the body, which is created of the substantial and persistent bone and the evanescent and disappearing breath, and which is made whole by those two parts of being. This is a poem about speaking, about the things the tongue says, and about what the bone remaining (after the tongue rots away) cannot say. It is about saying and not saying, seeing and not seeing, about what we can hear and read and about what we can no longer hear and read, because the human body, and the mind held within it as a warm and edible mass, has slipped away into nothingness.

So my handwriting, for this poem is simple. It is printing, but also simplified printing, regularized handprinting. Its letters are bonelike, being as formed as they need to be to be understood. The cross of the t never crosses the t.

The way a word is written by the hand is how it means.

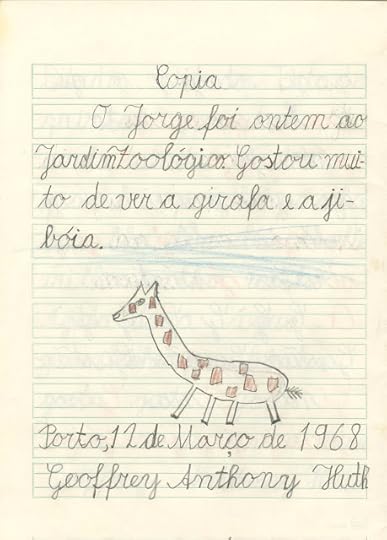

Geoffrey Anthony Huth, "Copia" (12 March 1968)

Geoffrey Anthony Huth, "Copia" (12 March 1968)Two weeks ago, my friend Scott Helmes, one of the most talented (and, thus, most modest) of artists I know, visited this area to attend the opening of exhibition featuring dozens of collaborations between him and my good friend Anne Gorrick. Sometime during my visiting with the two of them, and others, Anne talked about the power of the hand, and the need to use the hand. She believes in what the hand can do when inhabiting an analog world, as do I. She believes that Scott has so trained his hand that he can produce these fluid and floral movements of ink that are utterly beautiful, as do I. And she believes that these handmade things we make are the better forms of art, that the digital is somehow deadened by a separation from the human, as I don't also believe.

So, to answer the question, after thousands of words, I regret any loss of knowledge, especially knowledge, that could lead to the creation of better art, and the loss of training in penmanship is a great one, even though it's one few people take advantage of. We do become, as I fully am, cyborgic by our reliance on machines to make our words for us. But every form of making, whether through digital machines or analog tools, is a possibility, and I do not want to abandon any possibility. Every tool has a set of meanings and a set of potentials that no other too has. So I don't extol the handmade over the machine-enabled.

Yet I am primarily a maker of poetry, visual poetry, by hand, though few realize this. Most of these creations no-one, no-one at all besides myself, ever sees. I make hundreds of handwritten or handmade visual poems a year, easily 500 in some years. They are small, granted, but they are things, they exist, and they persist, if only in folders. My hand is traine to make letters, and still I think my hand untrained for the job.

And I was trained since I was a small child.

At the age of six, while starting my schooling at the Deutsche Schule zu Porto in Oporto, Portugal, my teachers trained me in penmanship in a very prescribed way. Before I wrote any letters, before I wrote connected e's or s's in a row, I wrote shapes in a row. I was taught to repeat shapes and connect them to identical shapes, so much so that by the time I was seven I could write almost completely controlled letterforms around a drawing of a giraffe. Actually, I felt, I could feel in the fragile bones of my fingers, how writing was a form of drawings.

And I learned letterforms that I had to abandon when I returned to North America (though to Canada) to live. I gave up the open-bowled cursive p. I abandoned the curving tops and bottoms of my cursive and crossed majuscule Z. It was a temporary loss, though. Those tilde-like opening and closing strokes of the Z (and other letters) inhabit many of my fidgetglyphs, including "2'mNot," the tilde of which is merely a form reproduced just as I had learned it when I was six. An open-bowled p in a fidgetglyph feels different and means differently than a closed-bowl cursive p. And that H that begins the Huth in my seven-year-old's signature is the dramatic presence of self when it appears in a fidgetglyph. It was a form I had forgotten until I was found it stitched into a pillowcase in a hotel in Peru in 1974.

When I lived in Bolivia in the mid-1970s, I learned calligraphy, and (unlike, I assume, everyone else in that art class) I never gave it up. I have learned to honor the hand, and the handwriting it produces, to honor the careful placement of ink on the page.

Once our culture loses that knowledge entirely, or gives it over entirely into the self-subsumed artistic class of which I am an unwitting but willing part, it will lose part of its ability to read these signs. The same visual text will be before them, but they will see the equivalent of rongorongo before themselves, pictures that must mean something wordlike, but which appear to them as nothing but shapes or pictures, meaningless, but pretty, pretty meaningless, but pretty.

My father has the most controlled handwriting I have ever seen. He never has a rushed hand, though I have one so rushed that it can be almost unencryptable even by me after a few minutes. He presses the nib of his pen, often one of those black Department of State ballpoints that I lived with for so many years, and he for so many more. I think he understands the beauty of his hand, though he has never mentioned it. Instead, he extols the beauty of his father's hand and that of my sister Nini, but their hands are middling. They are workmanlike and readable but without any artistry to them. My father says none of his other children have good handwriting.

He has never, apparently, seen mine, because my need for handwriting is so deep that I see almost nothing but the flaws, my inability to make a perfect circle every time, an unintentional jog in a near-perfect curve extending half-way across a page, one bowl of a two-storey g a bit smaller than the next. I have often thought of artists like myself, artists who work in small ways outside of the glare of attention as nocturnal artists. And I have written almost every single one of these words here while sitting in the dark, with the only light being that of the screen and the keys of the keyboard before me. (This is my only musical instrument.) But artists such as myself, such as most of the artists I care most about, these cryptic and crippled visual poets, I also think of as invisible artist, because so little of our work is seen, because we reject the normal means of art-making for those we love the most.

So we are invisible even as we create things to see, things for the contemplation of the eye, things for the joy of the physical and inky word.

For dinner tonight, I ate one red pear, a hardboiled egg (browned, but peeled down to whiteness), and one half a red tomato. It was a sufficient and sustaining meal for a man of my relatively slight weight, especially after a day of more eating than usual.

While eating these pieces of food, I thought of the curves of their exteriors, the beauty and variability of them, and I imagined the fingers of my right hand drawing them into letters, into words, into meaning, into shapes taken into the body to be made something of there by the human mind.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on February 16, 2012 16:36

No comments have been added yet.