A Poetics (# 87 via # 57)

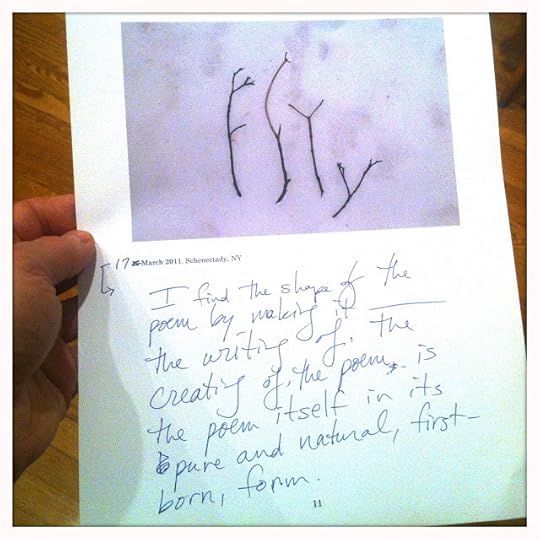

Geof Huth, The First Form of Entry # 80 of "A Poetics" (17 March 2011; photo: 13 December 2011)

Geof Huth, The First Form of Entry # 80 of "A Poetics" (17 March 2011; photo: 13 December 2011)What is, I am asked—sometimes with an intensity vergingon malice, sometimes with contorted confusion, sometimes out of an innocentcuriosity and desire to know—is the boundary between a poem and everythingelse? I am asked this question because a poem to me can be words arranged inlines on a page, words spoken into air, words scrawled on a page or moving on ascreen, shapes resembling letters but never taking the full form of text, songswithout the courtesy of words, or grunts and groans and nothing more—just theinarticulate articulations of the voice.

And I ask, What is the boundary between your body and theworld?

Does sound not enter your body and becomeindistinguishable from your thoughts? Are you not, even now, sucking air intoyour body, bringing the world into your body, just for the simple pleasure ofliving? When you eat the foods of the earth, when are they simply meat and eggsand apples, and when are they merely the substance of your body? the muscle ofyour arm, the hair of your neck, the nail grown just the nail, grown just a bittoo long, of your thumb?

And when you die, when are you no longer yourself? At themoment of death when your consciousness gives way to cosmos? At the point whenyour body becomes the temperature of world around it? When all the flesh hasfallen from your bones? Or when even your bones have crumbled away intonothing? After having defined yourself as a body for so long, when does yourbody not define you at all?

The more precise the line between poetry and somethingelse, the less I care about it. Not because I don't find the exerciseinteresting. I do. But because poetry has to be about possibility, andboundaries are more about pietics, about purity of thought instead of theelasticity of possibility.

But poetry means something to me—as a word withinquotation marks and as a concept.

Poetry is that art that we practice that has an intensefocus on language in any of its three incarnations (or any combination ofsame). In visual poetry, the focus is on the shape of the text, which mayinclude images, which may be wordless, which may consist of nothing butinvented textshapes. Visual poetry examines poetry primarily from the point ofview of the eye. In sound poetry, the focus is on the sound in the ear, so a soundpoem heightens the aural and may be about intense verbal gymnastics in terms ofmeter or music, or it may be about the examination of the sonic edge oflanguage: the sounds we can make that have no verbal meaning but which we canpronounce in ways that allow it to carry emotional meaning.

In textual poetry, sometimes called lexical poetry, whichis what most people think of when they think of poetry (that is, poetry inlines that sometimes is read alone, in loping cadence, from a page), the earplays a part because the poem is about the sound of words even when notsounded, the eye has its place because the poem's arrangement on a pagegoverned its expression from the body and gives silent hints to its meaning,but the poem is primarily for the mind, for the making of sense or thedestruction of sense through sense: it is about the meaning we make when wehear through the syntax of words held in place together.

Certainly, all of these are of the body and affect thebody, and all of these are of the mind, and force us to think, but these arealways emotional products of the self. We are meant to understand them with ourbody, with our mind, and with our heart, which are all the same thing, each oneindistinguishable from another, each more a concept than a fact, each the mostimportant pieces of our unique selves, themselves indistinguishable from theswirling mass of the universe twisting around us.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on December 13, 2011 20:59

No comments have been added yet.