Michael Lopp's Blog, page 56

January 24, 2011

Interview: Marco Arment

On my list of horrendously bungled acquisitions, I put Delicious near the top. Since its acquisition by Yahoo in 2005, the biggest user-facing change to the site was a visual refresh in 2008. Even with this rampant feature stagnation, I'd stuck with the site because it solved a daily need for me -- bookmarks anywhere.

Yahoo's strategic negligence is mind-boggling. In a world of exponentially increasing information, coupled with increasingly different ways of accessing it, the idea of investing in a social service that tells you precisely what your users care about strikes me as a no-brainer.

Fortunately, nature abhors a vacuum and Marco Arment's Instapaper has deftly stepped in to replace Delicious. I spoke with Marco via email to understand the origins of Instapaper, the valuable lessons he took from his first company -- Tumblr -- and how he manages one of web's most useful sites as a one-man shop.

RANDS: Where did the idea for Instapaper originate and how long until you had a usable product?

MARCO: In the fall of 2007, I had just switched to the iPhone, and I had a long train commute every day. I never knew what to read on the train, but I'd find stuff all day at work that I didn't have time to read, so I made Instapaper as a simple, one-click link-saving service for myself to time-shift links from the work day to my train commute.

The original web app took only a single night to write. It was usable, but it was very simple.

Over the next couple of months, I added a few useful features, most notably the "text" mode to strip articles down to iPhone-formatted text. This was so the EDGE-only original iPhone could download them quickly and keep more tabs in RAM without needing to reload them when I was potentially underground and offline.

When did you know you had something viable on your hands?

I just used it myself and didn't tell anyone for a few months. I then showed it to a couple of friends. After a week of using it, they were already raving that it was amazing and it changed the way they read, so I gave it a few nights of polish and posted a simple link to it on my blog.

Within days, it had thousands of users and was getting widespread acclaim. I had no idea it would get so big so quickly.

What's your favorite stat or fact regarding Instapaper?

Most people assume that online readers primarily view a small number of big-name sites. Nearly everyone who guesses at Instapaper's top-saved-domain list and its proportions is wrong.

The most-saved site is usually The New York Times, The Guardian, or another major traditional newspaper. But it's only about 2% of all saved articles. The top 10 saved domains are only about 11% of saved articles.

You're a one-man shop and are, among other things, developer, support, and operations -- how do you pull that off?

A lot of coffee and Phish.

Were there design decisions you made early on in order to manage that? What were they?

Absolutely.

The biggest design decision I've made is more of a continuous philosophy: do as few extremely time-consuming features as possible. As a result, Instapaper is a collection of a bunch of very easy things and only a handful of semi-hard things.

This philosophy sounds simple, but it isn't: geeks like us are always tempted to implement very complex, never-ending features because they're academically or algorithmically interesting, or because they can add massive value if done well, such as speech or handwriting recognition, recommendation engines, or natural-language processing.

These features -- often very easy for people but very hard for computers -- often produce mediocre-at-best results, are never truly finished, and usually require massive time investments to achieve incremental progress with diminishing returns.

If a one-person company is going to build a product, it can't have any of those huge time-sink features. At most, I can afford to have one or two components of moderate complexity, such as the HTML-to-body-text parser and the Kindle-format writer. But even those are barely worth the time that I put into them.

What were the biggest lessons you took from Tumblr that made the design, development, or deployment of Instapaper easier?

Tumblr didn't have a dedicated server administrator until a few years into its life, so I had to be our de facto server administrator in addition to my primary developer role from Tumblr's start until we had 48 servers handling about 5,000 requests per second.

Since that's a sizable infrastructure, but we had very little time to devote to maintaining it, I had to choose mature, stable technologies with great tools and very low administration needs. And I built Instapaper on the same technology: PHP 5 with a custom high-performance MVC framework, MySQL, Memcache, Apache, and CentOS, on high-end dedicated hardware.

This proved invaluable to both Tumblr and Instapaper, since I don't need to deal with webserver processes crashing, corrupted databases, or any serious platform issues. All of these tools are used by many other companies with deployments much larger than these, so nearly all of the bugs get worked out long before they get a chance to affect us.

The result of all of this platform conservatism is that I can spend my time improving the product in meaningful ways instead of fighting with my server software.

What part of Instapaper's infrastructure are you most proud of?

The bookmarklet has a mechanism to save pages from sites that require logins for full content, such as the Wall Street Journal and Harper's, by sending a copy of the page's HTML from the customer's browser to the server. It's like automating the "Save as..." menu item: if you have your own account for these sites and can see the page in your browser, you can save it to Instapaper.

The way it does this is ridiculous: instead of calling a simple GET request to save the page, since an entire page's contents would quickly overrun any URL-length limits in the stack, it injects a FORM with a POST action and populates a hidden value with the page contents.

But form-data requests from browsers aren't Gzip-compressed, so the resulting data is huge and needs to be sent over people's (often slow, often mobile) upstream connections. So I found an open-source DEFLATE implementation in Javascript -- really -- and the bookmarklet compresses the page data right there in the browser before sending it.

The whole procedure is hideously complex, but works incredibly well.

Instapaper integration seems ubiquitous in any information consumption application that's been released in the last year - how did that start?

This started as a fortunate side effect of having a few influential developers who were fans of Instapaper, most notably Loren Brichter (Tweetie, now Twitter), Craig Hockenberry (Twitterrific), and Brent Simmons (NetNewsWire), who integrated send-to-Instapaper features into their respective products a long time ago. And since the Twitter and RSS client markets are so competitive and innovate so rapidly, many other developers quickly followed suit.

Now, it's almost always a highly requested feature for new content-finding and content-consumption apps, especially on iOS. I'm just honored and humbled that it has become this widespread.

My impression is your feature development process is very iterative -- do you start with something that you want yourself and then slowly develop for your users? Does it work? How do you know when you're done?

That's correct. I don't plan specific, major releases very often -- I just incrementally build on the product in development, test features on myself for a while, cancel those that don't work, and roll up the successful ones into a release every few months.

Generally, I know I'm done because as I'm testing the migration from the current in-store version to the new version, I cringe at how bad the in-store version is relative to my shiny new development copy. I think, "I can't believe *that* is what customers are using right now, when they could be using *this*."

That's when I freeze new features, fix any known bugs, polish any rough edges, begin final testing, and prepare to issue the release.

What productivity tip have you discovered that now you can't live without?

Keep a to-do list.

A real one. One that you actually use and update throughout the day. It doesn't need to be fancy, like the getting-things-done task managers -- I use TaskPaper, which is essentially a text editor with optimized syntax highlighting for to-do lists, against a text file on Dropbox.

I've never been a note-taker. In high school, I was that smartass kid who never had any notebooks or anything on his desk in class. Just a blank desk to slowly fall asleep on. I thought I could just keep track of everything in my head, which is true in high school if you're a smartass slacker, but doesn't work very well after that.

If a task isn't written down in a list or set to alert me in iCal, it's gone. Forgotten. Doesn't get done.

Oh, and dump your cable TV service. Get the shows you actually enjoy from iTunes and Netflix and stop wasting time watching whatever's "on".

What's your favorite thing to do when you're not being an engineer?

I love to write. Not anything substantial, like novels or stories -- just blog posts. Writing about a subject helps clarify, mature, and sometimes even change my opinion on a topic. Afterward, I feel accomplished and productive, and the responses I get are fulfilling, constructive, and often more numerous than I expect.

January 17, 2011

Managing Nerds

Ten years ago, the world was collectively freaked out by the Y2K bug. The idea was that when innumerable software-driven clocks flipped at midnight from 1999 to 2000 that the digital shit was going to hit the fan. I blame the origin of the world-wide freak-out on the nerds.

Y2K collectively freaked out the nerds because every single software engineering nerd has had the moment where he looked across the table at someone important and said, "Yeah, I fixed that problem, but I have no fucking clue why it's working. It's a total mystery." Nerds have been repeatedly bitten by previously dismissed and seemingly impossible edge cases that we believed there was no possible way for a regular human to encounter.

We've been shocked how often a demo has become a product. We know that it is an inherent property of complex systems that they will contain both our best work and our worst guesses.

I call this state of mind the Nerd Burden. It's a curse put upon nerds who know how a system works, and, more importantly, what it took to build. Understanding the Nerd Burden is a good way to get into a nerd's mind and start to figure out how to manage them.

A Worst Case Scenario

This is an article on nerd management. The usual requirement of nerd management is that in order to manage nerds, you need to be one. For the sake of this article, I'm assuming a worst-case scenario -- you are not a nerd, but your job involves daily nerd management. My condolences, these guys and gals can eat you alive.

A good place to get mentally limber regarding nerds is with The Nerd Handbook. This is intended for the significant others of nerds and geeks and it's a good place to start understanding the nerd mindset. However, where the Handbook explains the care and feeding of nerds in the home, this piece is concerned with nerds at work.

Multiple generations of nerds are in the workforce now, so your preconceived notions of nerdery are not as useful as you thought. Discard the nerd extremes: the curmudgeonly pocket protector set is retiring or retired and there's a good chance that the slick brown-haired guy sitting across the bar wearing the $300 Ted Baker shirt is a fucking Python wizard.

Fortunately, a career as a nerd in software engineering still requires a well defined mental skill set, not any particular sartorial flair, and successfully acquiring and refining that skill set has tweaked the nerd's brain in a unique way that will start to define your nerd management strategy.

Disclaimer: As with all of my articles, I use "he" as a convenience. There are plenty of female nerds out there and they display much of the same behavior.

A Problem

In front of you is The Problem. While I don't know what The Problem is, I do know that you have a bright team of talented nerds working for you, and I know that you don't have a clue how to tackle The Problem: you need the nerds and you don't know where to start. The Problem is unique in that your normal leadership moves aren't going to work. You can already predict the collective nerd reaction and it's the opposite of what you need to happen.

Rather than attacking this Problem directly, let's turn it around and explore the inner workings of your nerd's mental landscape for inspired next steps.

The nerd as system thinker is a point I've been making since The Nerd Handbook and one I explore further in Being Geek. Briefly, a nerd is motivated to understand how a thing works -- how it fits together. This drive comes from the nerd's favorite tool, the computer, which is a blissful construction of logical knowability. Years of mastering the computer have created a strong belief in the illusory predictable calm that emerges from the chaos as you consistently follow the rules that define a system.

If I had to give you a single piece of managerial advice, I would say: "Your job with your nerd is to bring calm to their chaos". Let's begin.

Your nerd treasures consistency. Your staff meeting is an entertaining affair. You keep it light, you relay developing corporate shenanigans, and you crush rumors as best you can. Occasionally, you need to make a decision on the spot -- random policy enforcement: Should Kate get that sweet office with the window?

You: "Sure, Kate deserves it... she's doing great work."

Suddenly, a normally chatty staff meeting is full of silence. What happened?

First, you nonchalantly barged your way though one of the three guaranteed topics that will cause anyone, not just nerds, to lose their goddamned minds: space, compensation, and titles. Second, your off-the-cuff decision regarding Kate is somehow inconsistent with your team. Remember, you are sitting in a room full of nerds who -- just for intellectual sport -- are parsing every decision you make, analyzing it, and comparing that analysis against every single decision you've ever made in their presence. That silence? That's the silent nerd rage that arrives when they discover meaningful inconsistency.

The rules regarding who gets a window have never been written down, but they are known: you are either a manager who needs to have 1:1s or you've been with the group for multiple years and you have senior in your title. Kate has neither, and while her great work might be cause for awarding her the office, by not explicitly stating that there is an addendum to the unspoken rules regarding office windows, you are in consistency violation. You are less predictable because you are no longer following the rules of the system.

A predictable world is a comforting world to your nerd. Your inconsistency on the office ruling now has them wondering, "What the hell other random crap is coming down the line? How the hell am I supposed to get my work done when my boss engages in fits of randomness?" According to your nerd, a predictable world is a world where we know what is going to happen next. See...

Your nerd also treasures efficiency. When a nerd is mentally noting every single decision that you make, they're not doing so because they want to catch you in a lie or an inconsistency, that's just upside. What the nerd is doing is what they always do -- sifting though impressive piles of information and discovering rules so they can discover the optimal system that governs everything. Grand Unification Theory? Yeah, a nerd invented that so he could sleep at night.

With an understanding of the rules, your nerd can choose a course of action that requires the least amount of energy. This isn't laziness; this is the joy that in a world full of chaotic and political people with obscure agendas and erratic behavior, your nerd can conquer the chaos with logical, efficient predictability. Your nerd has a deliberate goal in mind that you need to support. Your nerd is...

Chasing the Two Highs

In The Nerd Handbook, I called this the High, but there are Two Highs:

The First High: When the nerd sees a knot, they want to unravel it. After each Christmas, someone screws up the Christmas tree lights. They remove the lights from the tree and carefully fold the lights as they lay them in the box. Mysteriously, somewhere between last year's folding and this year's Joy of Finding the Lights, these lights become a knotted mess.

The process of unknotting the lights is a seemingly haphazard one -- you sit on the floor swearing and slowly pulling a single green cable through a mess of wires and lights and feeling like you're making no progress -- until you do. There's a magical moment when the knot feels solved. There's still a knot in front of you, but it's collapsing on itself and unencumbered wire is just spilling out of it.

This mental achievement is the first nerd high. It's the liberating moment when we suddenly understand the problem, but right behind that that solution is something greater. It's....

The Second High: Complete knot domination. The world is full of knots and untying each has its own unique high. Your nerd spends a good portion of their day busily untying these knots, whether it's that subtle tweak to a mail filter that allows them to parse their mail faster, or the 30 seconds they spend tweaking the font size in their favorite editor to achieve perfect readability. This constant removal of friction is satisfying, but eventually they'll ask, "What's with all the fucking knots?" and attack.

A switch flips when your nerd drops into this mode. They're no longer trying to unravel the knot, they want to understand why all knots exist. They have a razor focus on a complete understanding of the system that is currently pissing them off and they use this understanding to build a completely knot-free product - this is the Second High.

Chasing the Second High is where nerds earn their salary. If the First High is the joy of understanding, the Second High is the act of creation. If you want your nerd to rock your world by building something revolutionary, you want them chasing the Second High. This is why...

You obsessively protect both your nerd's time and space. Until you've experienced the solving of a seemingly impossible problem, it's hard to understand how far a nerd will go to protect his problem solving focus and you can help. The road to either High is a mental state traditionally called the Zone. There are three things to know about the Zone:

The almost-constant quest of the nerd is managing all the crap that is preventing us from entering the Zone as we search for the Highs. Meetings, casual useless fly-bys, biological nuisances, that mysterious knock-knock-knocking that comes from the ceiling tiles whenever the AC kicks in -- what the nerd is doing in the first 15 minutes of getting in the Zone is building focus, and it's a Jenga-like construction that small distractions can topple.

Every single second you allow a nerd to remain in the Zone is a second where something fucking miraculous can occur.

As I've explained before, your nerd has built himself a Cave. It might not actually look like a cave, or maybe it does. The goal around its construction is simple: protect the Zone so we can chase the Highs. Stand up right now and walk to each of your nerds' offices and spelunk the caves. Ask the question: "How are they protecting their focus?" Back to the door? Headphones? Massive screen real estate? You don't have to ask a single question to begin to understand what your nerd does to protect his Cave. You need to ask...

What is your nerd's hoodie? I write better when I'm wearing a hoodie. There's something warm and cave-like about having my head surrounded -- it gives me permission to ignore the world. Over time, those around me know that interrupting hoodie-writing is a capital offense. They know when I reach to pull the hoodie over my head that I've successfully discarded all distractions on the Planet Earth and am currently communing with the pure essence of whatever I'm working on.

It's irrational and it's delicious.

Your nerd has a hoodie. It's a visual cue to stay away as they chase their Highs and your job is both identification and enforcement. I don't know your nerds, so I don't know what you'll discover, but I am confident that these hoodie-like obsessions will often make no sense to you - even if you ask. Yes, there will always Mountain Dew nearby. Of course, we will never be without square pink Post-its.

Don't sweat it. Support it. Also, understand the interesting potentially negative by-products of all this nerdery, such as...

Not invented here syndrome. When you ask your nerd to build something significant, your nerd is predisposed to build it himself rather than borrowing from someone else. Strike that, your nerd's default opening position when asked to build a thing is: "We can build it better than anyone else".

First, they probably can, but it's an expensive proposition. Second, understanding why this is their opening position is important. The ideal mental state of the nerd with regard to The Problem is the First High - a completely understood model of the problem. The issue is each nerd's strategic approach for this high is different.

Unfortunately, code is often the only documentation of our inspiration and your nerd would rather design his own inspiration than adapt someone else's. When a nerd says, "We can build it better," he's saying, "I have not devoted the necessary time to understand the existing solution and it's more fun to build than to investigate someone else's crap."

If your nerd is bent on building it versus buying it, fine, ask him to prove it. Make the Problem the explanation of why building the new is a more logical and strategic approach than pulling a working solution off the shelf.

The bitter nerd. Another default opening position for the nerd is bitterness -- the curmudgeon. Your triage: Why can't he be a team player? There are chronically negative nerds out there, but in my experience with nerd management, it's more often the case the nerd is bitter because they've seen this situation before four times and it's played out exactly the same way. Each time:

Whenever management feels they're out of touch, we all get shuttled off to an offsite where we spend two days talking too much and not acting enough.

Nerds aren't typically bitter; they're just well informed. Snark from nerds is a leading indicator that I'm wasting their time and when I find it, I ask questions until I understand the inefficiency so I can change it or explain it.

The disinterested or drifting nerd. Your nerd won't engage. It's been a week and a half and as far as you can tell, all he's done is create and endlessly edit a to do list on his whiteboard. Whether he's disinterested or drifting, your nerd is stuck. There are two likely situations here: he doesn't want to engage or he can't.

Triage here is similar to Not Invented Here -- is the problem shiny? Is there something unique that will allow for the possibility of original work? Ok, it's shiny - is it too shiny? Is your nerd outside of the comfort zone of his ability? My favorite move when a nerd appears stuck is pairing him with a credible technical peer - not a competitor, but a cohort.

Once you've discovered the productivity of the Highs, you're going to attempt to invoke them. Bad news. The invocation process is entirely owned by and unique to your nerd. You can protect the cave and honor the hoodie, but your nerd will choose when to go deep. The amount of pressure you put on your nerd to engage is directly proportionate to the amount of resistance you'll encounter.

Find a cohort. Someone who will be receptive to the perceived lack of shininess or someone who will say the one thing necessary to get your nerd chasing the Highs.

The Nerd Burden

I've spent a lot of time painting nerds as obsessive control freaks bent on controlling the universe. Fact is, your nerd understands how the system works. They know what you know -- chaos is a guarantee. It's neither efficient nor predictable, but it's going to happen.

You and your nerd are surprisingly goal aligned with regard to the chaos. You want him to build a thing and you want him to build it well. You want it to perform reliably in bizarre situations that no one can predict. You want to scale when you least expect it. And you want to be amazed.

Amaze your nerd. Build calm and dark places where invoking the Zone is trivial. Perform consistently and efficiently around your nerd so they can spend their energy on what they build and not worry about that which they can't control. Help them scale by knowing when they're stuck or simply bored. And let them chase those Highs because then they can amaze everyone.

December 13, 2010

Seven Precious Books

As I talked about in The Book Stalker, there are books I need on my desk, books I need in the room, and books I just need to know exist. The following seven books are the precious ones I referred to in that article and they each serve a specific purpose.

It strikes me the holiday season is a good time to not only reflect on this purpose, but to honor these books by sharing them with friends.

Universal Principles of Design. Software engineers and designers need to party - together - more. There is no more evidence necessary that when engineers and designers muck around in each other's business that customers are more likely to be rabid about the final product. Now, most engineers' knowledge of design is a vast wasteland, but you can take matters into your own hands.

The Purpose: Think of Universal Principles of Design as 125 independent, digestible blog articles that provide convenient access to cross-disciplinary design knowledge. Like many of the books on this list, all you need to find value in this book is to open it... to any page. Why does highlighting matter? How much can a user actually remember? Why should I care about interference effects?

Universal Principles of Design does not give you a playbook for dealing with designers. It constructs small bridges of knowledge into the design world; it gives you convenient places to start thinking about design in your every day so you can start to form a design opinion. And that's how the party starts.

Writing Down the Bones. Written in 1986, Natalie Goldberg's book on the craft of writing is one of the few books on the desk. My copy is brand new, but only because the prior two copies have crumbled due to use. Goldberg's chapters are short and NADD-friendly. Her style blends conversation and content, making her lessons easily approachable.

Writing Down the Bones. Written in 1986, Natalie Goldberg's book on the craft of writing is one of the few books on the desk. My copy is brand new, but only because the prior two copies have crumbled due to use. Goldberg's chapters are short and NADD-friendly. Her style blends conversation and content, making her lessons easily approachable.

The Purpose: I open Writing Down the Bones whenever I need a writing tune-up. Whether I'm stuck on a word, sentence or chapter, Goldberg's advise is not only simple and clear, but enthusiastic: Push yourself beyond when you think you are done with what you have to say. Go a little further. Sometimes when you think you are done, it is just the edge of the beginning.

Goldberg builds writers.

Accidental Empires. Robert X. Cringley used to write a gossip column you could respect. It was never quite clear whether his column in InfoWorld was based on fact or not -- the answer was somewhere in between -- but for a nascent software and hardware industry, his column was everything Valleywag failed to be.

The Purpose. Like his column, it's clear Cringley has layered a generous amount of fiction on the stories surrounding the defining moments of the likes of Microsoft, Apple, and Adobe, but it's a delicious fiction. Who cares whether Bill Gates was arrested for reckless driving? It's a set of compelling stories about the earliest days of our industry, complete with nerd heroes, egotistical, coke snorting jerks, and the continual expectation an amazing new product was always just about to be released.

Looking for Rachel Wallace. When I signed up for "The American Detective" class in college, it was a throwaway literature class. Read five books, write two papers -- no problem. I've since forgotten all of the books and authors we read that semester; all of them save for Robert B. Parker.

Looking for Rachel Wallace. When I signed up for "The American Detective" class in college, it was a throwaway literature class. Read five books, write two papers -- no problem. I've since forgotten all of the books and authors we read that semester; all of them save for Robert B. Parker.

Parker's defining character is Spenser, a well-educated, smart mouthed chef who also happens to be a private detective. Parker's mysteries are uncomplicated and mostly irrelevant. Where Parker shines is a deep focus on characters and the conversations that tie them together. That strength is far more important than the whodunit. You will care about the characters Parker defines; you will laugh with them; and you will wonder how you can know a person, who you will never meet, so well.

The Purpose: Looking for Rachel Wallace just happens to be the first Parker novel I read, but you can read any of them to get a sense of Parker's style. I read a Spenser novel when I need a constructive reminder about the importance of voice having character. If you want to know where the Rands' voice formed, you can ask Spenser.

Microserfs. This book first appeared as a short story for then-vibrant Wired magazine. Like when the Challenger exploded, I vividly remember where I was sitting and what I was wearing when I realized: This is me. This is what I do all day. These are the strange people that surround me. People will believe this is fiction because it's so odd, but it's real -- every day real.

The Purpose: Microserfs' role on my must-re-read shelf has changed over the years. It's evolved from a "this is my life" re-read to a "remember how it used to be" retrospective. I re-read it to remember that we work in a strange industry populated with odd characters that build the future with their minds.

Astonishing X-Men Omnibus. There are lots of reasons to appreciate Josh Whedon's nerd ability as the creator of Buffy, Firefly, and Dollhouse. Oddly, I never fell under the spell of any of these fine pieces of work, but I've read Whedon's Omnibus cover to cover a dozen times.

Astonishing X-Men Omnibus. There are lots of reasons to appreciate Josh Whedon's nerd ability as the creator of Buffy, Firefly, and Dollhouse. Oddly, I never fell under the spell of any of these fine pieces of work, but I've read Whedon's Omnibus cover to cover a dozen times.

The Purpose: I grew up with many of the characters that join to form the core of Astonishing X-Men, and then proceeded to spend the following decade ignoring them. The X-Men movies were entertaining but shallow popcorn versions of the characters I knew.

Whedon's love for the X-Men exists on every single page of this gorgeous, hilarious and heart-wrenching collection. When I re-read this opus, I pleasantly leave the Planet Earth and remind all those around me that you should never underestimate the ability of a nerd to escape to an impossible world.

Phaidon Atlas of 21st Century World Architecture. I know nothing about architecture. Zip. Nada. Never had a class. However, I am excellent at looking at it. Phaidon's hefty book on architecture is a stunning collection of architecture around the world. The book's size gives the designers of the book room to land huge glossy photographs of works from every part of the globe.

The Purpose. Phaidon's book serves a single purpose for me: it provides a mental break from whatever the hell I'm doing. I move to the couch and open the book to a random page. Oh look, the swimming pool built in a Berlin as part of their failed attempt to get the 2000 Olympics.

It's stunning. Now where was I?

The random inspiration of others' work is a creative reset and a reminder that to do your best work, sometimes you just need to stop paying attention.

Happy Holidays.

November 11, 2010

The Art of Not

I sign up for every single beta, trial, or preview that crosses my inbox as a virtual land grab for the "rands" username. Yes, I am very interested in whatever bleeding edge thingamahoo you're up to, but the chances are this will be the only time I'm going to login into your service.

It is a function of my time, not your hard work. I've just searched for the word "invite" in the subject line of emails received since the beginning of the year and I'm looking at 20 new applications and services that showed up, and ironically, the one new service I'm using the most is the one for which I didn't get an invite.

Yes, there are exactly zero emails from Instagram in my inbox, and that's just the beginning of things they are successfully not doing.

Instagram Explained

Delivering the Instagram pitch is usually a study in disappointment.

Me: "You take pictures, tweak them with filters, and then share them with your friends."

You: "Yeah, I have three of those."

Same here. I grabbed Hipstamatic, took five shots, and didn't use it again. I checked out Photoshop Express and ran screaming. I still regularly use TiltShift Generator, but that usage pales in comparison to how Instagram has become part of my day, along with 300,000 others and counting. And that's with an impressive list of features Instagram doesn't offer, including:

A significant web presence: the interface is the iPhone application.

Options for rotating or otherwise altering your photos, other than 11 filters.

Complex social networking features.

Yet in a crowded market of low-end mobile photo editing tools, Instagram has become an overnight success. Why? They said no -- a lot.

The List of Not

Granted, one of the documented reasons for Instagram's spartan feature set is the size of the team. As noted in the Quora article, the team allegedly spent a year working on the foundation for what became Instagram. But it was in an eight-week period that Instagram was designed, developed, and deployed. They could have waited another eight weeks and added a bunch more features, but they didn't. I think each omission is interesting.

The lack of a significant web presence. Yes, you can share the URL for an individual photo via the website, but virtually all other interactions with Instagram are via the iPhone application -- the website is currently an afterthought. This type of product launch is a testimony to the buzz and strength of iPhone as a platform, but I think it speaks more to Instagram's tight focus on the one key workflow: "Grab a photo in a moment, make it better, and share it -- with everyone."

Nothing in that workflow needs to involve a traditional computer. Everything you need to participate in this workflow is sitting in your back pocket. Yes, the social angle of Instagram would be improved by a vast swath of eyeballs from the web, and I'm certain that's coming, but the opportunity for that feature to matter has been created by Instagram's choice to first intensely focus on the one workflow.

Limited options for altering photos. Ok, I didn't run screaming from Photoshop Express. It's a well-thought-out application that provides a solid set of photo editing tools, but after brief experiments I've never used it again for the same reason I've never written much of anything on my iPhone.

The interface of the iPhone is moment-based. You're in; you're out. Yes, I've lost many hours getting angry with Angry Birds, but for most interactions I want to get in and get out as quickly as possible. When I fire up Photoshop Express, the application asks, "Are you ready to spend the next 5-10 minutes of your life adding effects and borders to that photo of your cat?" The answer is no.

Other than cropping a photo to a pleasing Polaroid-esque square, the only options for photo alteration are a minimal set of 11 filters. No color correction. No brightness. No contrast. Where Instagram chose to invest their time (and yours) was choosing a diverse set of filters that seem to improve just about any photo.

Too dark? Try the 1977 filter. Flat color? How about X-Pro II? Too much color, but lots of detail? Try Inkwell.

The Instagram folks could've lost their frakkin' minds including any number of filters in their initial release, but they didn't. They picked a sweet spot for filters that improve just about any photo without overwhelming you with choices.

Minimal social. Unlike many of the other mobile photo editing tools, Instagram does have a social component. There's a backend service that uses a Twitter-like "we're sharing everything unless you tell us otherwise" privacy model, but similar to other Instagram design choices, the social angle is simple.

Instagram heavily leverages the work of others with their social strategy. You comb your Facebook and Twitter friend lists as a starting point for a follower list, but more interesting is Instagram's publishing feature set. It's one area that's feature rich. You can take your recently Instagramed photo and publish it to a bevy of services: Twitter, Facebook, Flickr, Tumblr, and Foursquare.

While this represents a lot of functionality, I still see Instagram's social angle as a study in Not. In the battle for eyeballs, Instagram knows they'll be more successful long term by not trying to be any of these established services, so they embrace them. Once again focusing on the last step of the workflow: "share it -- with everyone."

Regarding Product Market Fit

There's an inflection point in product development dubbed "product market fit". It's a milestone when a given service or product has found its market and can now focus on building a business.

It's comforting, the idea that there's a moment where you can safely say, "All that hard work has successfully resulted in our fit in this market ". Unfortunately, it's only an event you discover after it appears. It's a milestone, not a blueprint.

So, how'd Instagram do it? How'd they swoop into a cluttered market and grab 300,000 sets of eyeballs in eight weeks? Were they lucky? No. Did the have the benefit of examining the work of those that went before them? You bet, but that's not the biggest reason.

The Instagram team could have gotten lost in any number of distracting feature buckets. In fact, based on the Quora article, it looks like they did, but then they threw away that application and built one intensely focused solely on photos.

There's lots more coming from Instagram. There are subtle clues throughout the application that it could be adapted to share any type of media. Whatever they choose to do, they now have the opportunity to choose because of what they chose not to do.

November 4, 2010

Your Cat. My Socks.

We need to talk about your cat because your cat is pissing me off.

Your cat is eating my socks. No. Really. Your cat has eaten four pairs of my socks.

Yes, I know cats can't digest cloth. Your cat does not have super-feline sock-eating and digestion skills. Your cat nibbles the toes off my socks and then throws up these toe parts all over my closet floor as little gooey sockballs.

Your cat is pissing me off and we need to have a conversation about it.

The Topic of Conversation

In How to Run a Meeting, I describe a conversation as "verbal ping pong... you bat the little white verbal ball back and forth until someone wins". This describes a simple conversation, but conversations are rarely simple. They have a variety of structures that are carefully negotiated and molded by the participants.

To understand the different type of structures, we need to define a base unit of conversation and the actions that potentially surround it. Let's call this base unit of conversation a topic.

A topic is the headline you'd give to the current content and state of the conversation. Examples:

The problem with our bug queue.

I can't stand Stan.

You are bugging me in indescribable ways that I will now attempt to describe.

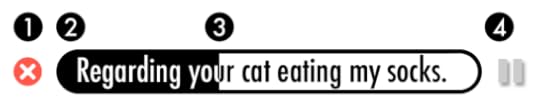

In my head, a topic looks like this:

The key parts of this model are:

Stop button. For any number of reasons, a conversation can stop or be interrupted. When this occurs, all conversation participants are effectively agreeing: "This topic is done and there will be no further discussion during this conversation".

The agreed upon Topic of the conversation.

Progress Bar. This is a totally subjective measure that indicates how close a conversation is to being resolved. If the bar is moving, this topic is currently in play.

Pause button. A healthy conversation is rarely only focused on a single topic. Conversations meander from one topic to the next. When paused, a topic is no longer being discussed, but it remains open and unresolved in the minds of the participants.

This is a lot of preamble to describe an act we do automatically. If this model strikes you as overly complex, know this -- you are going to spend half of your goddamned life suffering through the alignment of differing perspectives in any given conversation. It's the single biggest waste of your time in dealing with other people and the better you understand, the less time you'll waste. So, let's circle back to...

Your Goddamned Cat

As we sit down to have our conversation regarding the sockballs littering my closet floor, I'm thinking about how I'm going to successfully convince you to keep your cat on a tighter leash. In fact, I don't want the cat in the house at all, but you pay half the rent and we did agree when we arrived that the cat was cool. I need to figure out how to verbally amend that agreement, which means we're going to need to negotiate. I'm going to have to concede something in order get the goddamned cat away from my delicious socks and out of the house.

In this case, I don't know what my concession is -- it's something we need to discover via our conversation, which means there are a couple of potential topics:

Regarding your cat eating my socks.

The cat eviction negotiation.

Things I know that piss you off.

With these topics in mind, our conversation starts gently, in the living room. I explain, "I would like to discuss the matter of your cat eating my socks," to which you respond, "I am sick and tired of you not cleaning the bathroom".

Whoa. Wait. What?

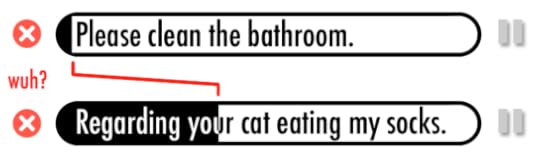

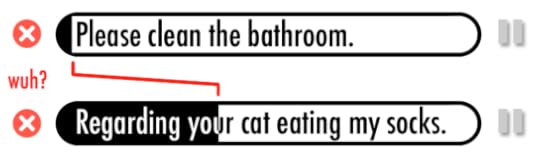

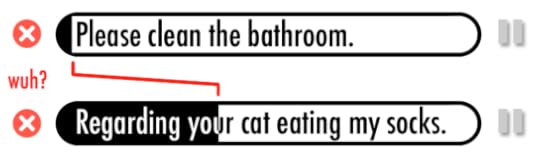

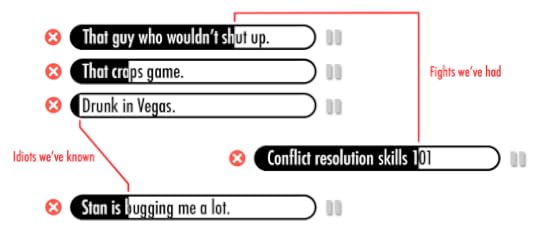

In my head, the conversation looked like this:

But you just hit the pause button on our first topic and started another topic:

The second topic introduces a new element in the model -- the segue. This handy line is the context that ties one topic to another, which, in the case of the sockball situation, is currently a confusing, "Wuh?"

The point: it takes at least two people to have a conversation, but the real work is in making sure you're both having the same conversation.

I can help.

A Conversation Structure

In computer science, there's a concept called data structures. The idea is that a data structure is a model used to organize data so that it can be used efficiently. One of the simplest structures is called a list and it looks like this:

In terms of a conversation, think of lists as the most basic and easy to follow type of conversation. Using the model I describe above, no topic can be paused or stopped until the topic is resolved. There are no segues, tangents, or sidebars.

You're thinking conversations as simple and structured as these don't exist, and you're right. This type of meeting does occur, but it's called a presentation -- where the speaker is click-click-clicking through his topics on his merry way towards the undisputed end.

While this basic list of conversations doesn't exist, there are people who want them to exist and will make this clear as part of the conversation. They sound like this:

"Wait, wait, wait, we're not done with topic #1. Can we talk about topic #1?"

"Hold it, before we go there, what about the issue at hand?"

"This new topic has absolutely nothing to do with what we're talking about."

The intricacies and implementation of various data structures are not the topic of this article. What's relevant is understanding that there are different conversation models you might find yourself in and then figuring out how to adapt.

The Stack

A slightly more complex data structure, and one that is more representative of a real conversation, is the stack. This is where our Pause and Stop buttons come into play. Let's go back to that goddamned sock-eating cat to understand. Our conversation started with the sock topic, but you immediately put a Pause on that first topic and fired up a new one. In my head that looks this:

This is a stack. The topics are literally stacked on top of each other because, in my head, we're actually talking about both topics, and the successful conclusion of all topics is key to this entire conversation coming to a successful conclusion. The question is are we both prepared for this type of conversation?

My definition of an effective conversation is if, at any moment, you could ask any participant in the conversation to point at precisely which topic was being discussed and how that topic was progressing. Bonus points for walking through the stack and explaining how you got there.

When conversation participants lose the context of the conversation, when they lose track of where they are, they stop listening and stop participating. The conversation no longer has a chance of resolution because resolution requires their active involvement and all they're doing is fake listening to your speech.

Conversation Tolerances

A stacked conversation, one with multiple topics tied together with segues, is where everyone involved needs to keep track not just of the complexities of the conversation, but of the tolerances of those participating. Again, this is not a meeting with a well-defined agenda and anointed leader; this is a conversation where everyone needs to keep their wits about them.

When a conversation gets complex, this is what I'm watching for:

How many open topics can we handle? Each segue moves us slightly further from the starting topic. Are you cool with that? Ok, how many topics can you keep in your head? There's a point where everyone will lose track of where they are if we have too many open topics -- what's your threshold? Wait, now I'm lost, so I'm going to ask: "How'd we get here?"

What's our segue tolerance? How deliberate do I need to be switching from one topic to the next? Do I need to explicitly say, "We are switching topics now," or can you keep up? How much segue detail do I need to give? Can anyone hit Pause and pivot to a new topic? Will you? Ok, you just did, but I don't understand your segue, so I'll ask: "Please explain how this relates to that."

What's our closure tolerance? How much progress do you need to make before we switch topics? Will you get cranky if we don't even try to resolve something? Is this topic more important to you than other open ones? Will you freak out if all is not resolved? Can the conversation totally mutate into something else? Is that a bad thing?

Understanding both your own conversation tolerances as well as the ones of those you converse with is essential to having a successful conversation, and the best way to know where they're at is to look. Humans wear a bevy of visual cues that indicate their comfort with a conversation. Nods, sounds, and eye contact -- these are potential signs of engagement. The rule is, if they look lost, you ask: "What did you just hear?" If you're lost, you say: "I'm not following you."

The Tree

Problem solving is the art of a finding a solution acceptable to everyone in the conversation. If everyone knew the solution to the problem, you wouldn't be having the conversation in the first place. If there is no problem, then, well, you're shooting the shit. Problem solving means getting conversationally creative, and being creative means letting yourself mentally wander -- eschewing structure. This is why my favorite conversation structure is the Tree.

The Tree is the pinnacle of advanced conversations. Where a stacked conversation looks like this:

The tree appears chaotic:

The simple explanation of the Tree conversation is that it's multiple conversations. In the image above, you're looking at three seemingly disparate conversations, except they're not. The reality and the definition of the Tree-based conversations are the inspired segues. Think of a conversation with your best friend. Would anyone listening to this conversation actually be able to follow it? Could they diagram it? Of course not.

Could you? Of course.

For qualified participants, the Tree is pure conversational joy. Topics vary wildly, being held together by only the thinnest of segues that are often unspoken, but there is a structure. And more importantly, there is mutual understanding and appreciation of this wonderfully chaotic verbal mess, because it's in this mess where you have the most potential to resolve the topic.

Remember, this is a conversation; it's not a story and it's not a meeting. There is a topic to be resolved and no one is happy until that topic is resolved. If this was a trivial topic, if we could just tell your cat to stop eating my socks. Resolution might be easy, but it's not. My spoken frustration about your sock-eating cat has triggered your response about my inept cleaning skills, which means now we're going to do some heavy-duty roommate therapy.

The resolution might be tricky and it might involve verbally wandering to disparate topics, but you and I have known each other for years. We're ok with a deep stack of topics that eventually transform into a forest of conversations. We know that part of big discovery is verbally wandering into strange mental places.

October 26, 2010

How to Be a Douche

Douche is trending.

I'm going to start by saying this is a dangerous article to write because an article that attempts to define the characteristics of douchery is, well, kind'a douchey. However, usage of the word douche has been on the rise in current culture and I believe I know why, so I'm going to risk it.

In the preface to Being Geek, I briefly explained the definitions of geek, nerd, and dork. While my research found no meaningful distinction between nerd and geek, the term dork was interesting -- while being a geek about a topic (say a music geek) means that you are self-declaring that you deeply appreciate a thing, dork is used by geeks to position their geekery above another geek's field. For example, I'm a computer geek, but those movie geeks are dorks.

See?

It'd be easy to simply map douche to dork and say that douchery was in the eye of the beholder, but I think there is something bigger going on with douche. The label of douche, while slightly hilarious, is also slightly serious.

The Douche Spectrum

To begin to understand the deviousness of the term douche, we need to explore its basic usage. There are three douche use cases:

Self-declaring as a douche -- "I can't figure out how to write this bio without sounding like a douche." A mostly harmless usage.

Labeling as douche in person -- "Your unearned high self-esteem... is kind'a douchey." Again, a face-to-face douche label is, in my opinion, just good constructive criticism.

Lastly, labeling as douche in absentia -- "I'm tired of his transparent self-serving bullshit. He's a douche". In an Internet full of individuals screaming for attention, this label is the kiss of death. Here's why:

The Sell

If you're taking the time to create and post content on the Internet, you are in the sales business. You're interested in someone buying the content; otherwise you'd be quietly taping that content to the wall of your office.

Rands, I want no money. There is nothing to buy.

Doesn't matter. Just because you're not charging for it, doesn't mean you're not selling it. Yes, there's a wide spectrum to selling varying from "I'm selling you on this idea" to "Please buy this poster regarding how to pet a cat", but the act of sharing something with the Planet Earth has a very different motivation than sharing with yourself, and it's within this act that the dangerous label of douche is hiding.

A Douche Criteria

The label of douche is the end result of a confluence of terribly subjective and contextual cues. As I'm reading your writing or watching your presentation, I mentally measure the following:

Are you for sale? Is it clear that your opinion is being motivated purely by money? Can I literally see the monetary strings dragging you hither and fro? Can I hear your thoughts above what is clearly your business plan? Am I hearing what you're selling before what you think? Are you never missing an opportunity to self-promote?

Is fame your goal or a consequence? Is your content deliberately inflammatory because you like to see shit burn? Are you enthusiastic with purpose or just annoyingly enthusiastic? Are you just trying to get attention? Wait, are you telling me you're famous? Really?

Are you human? Are you letting a bit of yourself into your ideas? Can I see you thinking? Do you have moments of humility? Empathy? Where do you end and your ideas begin? Are you just a mouthpiece? Can I discern your motivation?

Is there substance to your style? Did you earn your arrogance? Are you adding something substantive to the planet or are you just noisy? Are you pitching refinement as a mask for aggressively bad taste? Do I have a sense of your experience? Are you beating me over the head with it?

Are you aware that anyone else is here? Are you giving me room to think? Do you speak without understanding consequence? Are you aware of the world around you? Are you transparently self-serving?

Are you a douche?

The Douche Threshold

What matters to you is different than what matters to me. I have a douche hot button -- blatant self promotion -- but you couldn't care less. Still, when you label someone a douche, I giggle bit and then I wonder, "What do you actually mean?"

In this age of the empowered individual voice, we are flooded with opinions in blogs, tweets, and likes. As a means of managing this flood, we need a mental model to partition these unincorporated individuals -- we need a new vocabulary regarding who is worth listening to and not -- I believe that is why the term douche is trending.

The extreme subjectivity of the Douche Criteria can get you in a lot of trouble. If I had to boil all of the criteria down, I'd say the lazy version of the Douche Criteria is, "Do I like you?" Human beings are most comfortable when surrounded with those who look and sound alike -- who share the same values. Outsiders are viewed first by their differences rather than their potential. Yeah, it sucks.

My optimistic hope is the Internet hides the individual differences that don't matter while providing a stage for ideas. This is why the term of douche is not a goofy label that says, "You're different", it's a personal and essential judgement of authenticity.

(This post would not exist without the fine suggestions of the very-non-douchey folks who follow me on Twitter.)

Michael Lopp's Blog

- Michael Lopp's profile

- 144 followers