Michael Lopp's Blog, page 54

January 15, 2012

A Design Primer for Engineers

For a word that can so vastly change the fortunes of a company, it's worth noting that no generally accepted definition of the word design exists. This means when your boss stands up in front of the team at that all-hands and says, "We'll have a design-centered culture," there's a good chance he's saying nothing at all.

But you keep hearing this word. More importantly, you hear the urgency behind the word. You hear that choosing to design a thing is an important thing to do and the person saying it is also important, so you nod vigorously while silently thinking, "I have no fucking idea what you're talking about and I'm pretty sure neither do you."

There is no more evidence required that a magical focus on design can transform a company. In order for this to happen, engineering and design need to party more together, but there's a fundamental tension between design and engineering and understanding that tension is a good place to start thinking about design.

A Fundamental Tension

To understand the historic tension between the designer and the engineer, you need to go back to when software became mainstream, and in my mind that was with the arrival of the Internet. Software had been around and making piles of money long before Netscape, but it became a worldwide phenomenal when anyone, anywhere could mail anyone else a picture of their cat.

The arrival of everyone (and their cats) presented a challenge to these early software development teams. These teams were used to working with early adopters and their particular needs. See, early adopters are willing to put up with a lot of crap -- it's part of the deal we have with them. "You get to play with the latest and greatest, but it may explode at any point." Early adopters are cool with these explosions because early adoption makes them feel, well, cool.

When everyone arrived, everyone didn't want explosions -- they just wanted it to work. Engineers hear "just works" as "they want fewer explosions", but that's not what everyone wanted. They wanted to send a picture of their cat in the simplest way possible. They didn't care about JavaScript, security, frames or plugins; they just wanted to mail a picture of their goddamned cat without the application exploding.

Design results in the tangible translation between engineering thought: "fewer explosions" and user thought: "reliable, one-click cat photo mailing". Good design manages to both showcase the best of engineering efforts while simultaneously hiding them from the user.

After working with a wide of variety of designers, my opinion is that the role of design is:

Understanding what most users want.

Prioritizing and focusing on the most important of those wants.

Using this knowledge to exceed user expectations.

In the mid 90s, we, as traditional engineers, were not equipped for the role I described above. We'd been trained as builders of bits, and we believed that because we could build bits that we could build usable bits, but we were actually good at designing good product for ourselves... not everyone.

We don't see an explosion as a bad thing because we're intimately aware of how the sausage is made. We know that when a program crashes, you just re-launch the application and get back to work. Most humans on the planet do not see a crashed application this way. They are, at the very least, alarmed when something explodes. They're wondering, "Did permanent damage just occur?"

A Note to the Designer and the Engineer

With apologies to the incredible menagerie of design folk out there, this primer primarily focuses on the design denizens and design practices that surround software development. Furthermore, this primer is being written by an engineer for engineers. While I've spent a good many years soaking in design, I'm not a trained designer and the following descriptions of your history and your craft will piss you off with their simplicity, imprecision, incompleteness, and engineering bias.

But we're doing the same thing to design folk. We are well intentioned, but because we haven't repeatedly experienced the essential details, we are ignorant of them. We assume the act of describing the work somehow is equivalent to doing the work and, wow, are we wrong, but we are in good company because every eager master of their respective craft does this.

Engineers are uncomfortable with ignorance, but worse, we're bad at asking for help outside of our domain of expertise. This primer is the first step at building a solid bridge between our professions. So, chill. This is not a definitive design guide, it's a place for engineers to start thinking about design and if you happen to learn something about how we think -- super.

The Acronyms Matter

The phrase "we need a designer" is likely the first time you'll hear about design as a freshly minted software engineer. You wonder, "Well, what are they going to do that I'm not already doing?" The answer is an impressively long list of work that is beyond the scope of this article, but a good place to start is three key acronyms.

Like any profession, design is chock full of acronyms, but I'm going to focus on the three that are going be bandied about now that your boss has decided that design matters.

#1 GD -- Graphic Design

How they see the world:

Unfortunately, the most common name used to describe the graphic designer is, confusingly, the designer. The reasons are two-fold: first, he was the first person hired to work on the product who had any skill set outside of engineering, and second, he was placed in charge of the "the pretty". Someone in charge saw the first working prototype of the product and said, "This looks like an engineer threw it together", (you nod) and "We need a designer to fix this up" (blank stare).

You: "Fix what up?"

Person in charge: "I don't know... it just needs to... look prettier."

Designers who have not yet bolted from this article, yet, are now standing on their chairs screaming at the screen as they read this: "I KNOW THAT GUY."

Yeah, I know him, too. He's an idiot, but he has good intentions.

The craft of the graphic designer is a visual one. Via applications like Photoshop and Illustrator, a graphic designer gives visual form to ideas. Yes, the work they do is pretty, but it isn't just pretty. It speaks. It has an opinion about what it is and anyone who looks at it can see the opinion. Yes, a designer gives your application or website an air of clean, credible professionalism, but a well drawn anything does little to make your product easier to use.

A breakdown occurs when the person in charge walks into the graphic designer's office and says, "You're the designer -- can you help de-engineer the product?" Now, like you, the graphic designer wants to do more -- they want more responsibility -- so even though they don't know how the product works or who your users are, they sign up, thinking, "Sure, I'm a designer, right?"

And they produce. They generate an eye-pleasing prototype in Photoshop that you just want to lick. The graphic designer has done something most engineers cannot, and while important design work has occurred, the design is not remotely done -- your product simply has a pretty face. And while it does matter how your product looks, it's equally important how it works.

For the end of each section of this primer, I've selected a set of three design-related books that have shaped my design opinion. Let's start with design essentials:

The Inmates Are Running the Asylum

Meggs' History of Graphic Design

Universal Principles of Design

#2 IxD -- Interaction Design

How IxD sees the world:

The interaction designer has a fascinating gig: they abstract function from form. Think of how you regularly navigate your favorite application. You follow a familiar path that we'll call a workflow: it's a series of mouse clicks and drags accompanied by your rapid-fire keyboard wizardry. This is your interface with the application.

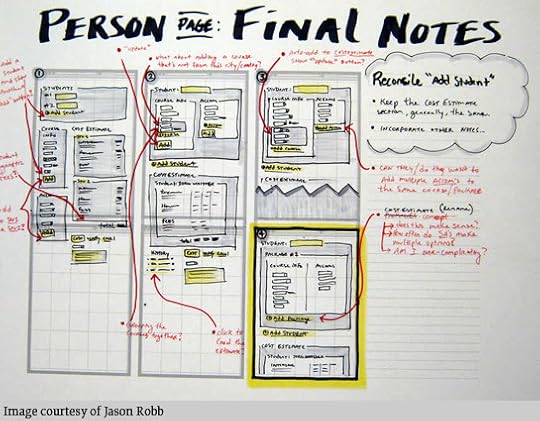

The interaction designer's gig is the care and the feeding of the workflow. Via the deft usage of wireframes and flowcharts, the interaction designer defines and refines the step-by-step process by which a user can traverse the application.

These low fidelity descriptions of the functionality are confusing to those who don't understand their intent. Is this how the application is going to look? No, this is the interaction. These are rough approximations of the user interface intended to describe how it will work, not how it will look. But how is it going to look? Could we get drop shadows on that text? I love drop shadows and blue, I love words with a punch. Yeah, ok, right -- you need to leave now. The door is down the hall on the left and it's a lovely shade of blue.

The separation of function from form involves making a mental leap and there are those who believe one cannot be considered without the other. I believe the answer is somewhere in the middle. While I don't believe you need pixel-perfect comps in order to think strategically about interaction, I do believe working prototypes with sample interaction and animation is a far richer place to have a debate than a whiteboard.

A low-fidelity scribble can describe how your product works, and it does remove many of the subjective elements of design that are apt to derail a perfect good design conversation into a useless debate about drop shadows. But color, typography, spacing -- all of these elements contribute to the feel of your product, and how your product feels is equally important to how it works.

There are two other acronyms in close orbit to IxD that you're likely going to discover that are worth mentioning:

IA or Information Architect is a title falling out of favor in recent years. Perhaps the best model for thinking about IAs is the role of a librarian. The mindset of information architects is what gave us the Dewey Decimal System: a classification system for information. An IA does not sleep well until information has been organized. I haven't run into one of these folks in a while.

HCI or Human Computer Interaction is another title you'll discover. It appears this title is one granted exclusively from University and those sporting this title first self-declare their degree, then pause, then add their University. Yes, I have a PhD in HCI from Carnegie Mellon.

My experience with the HCI folk is that they are often brilliant researchers. If you want to understand every possible workflow your users are trying on your application, the elapsed time to complete these workflows, and the enumerated set of quantified emotional damage these workflows are inflicting on your users, find an HCI guy, give him 18 months, and you'll be dazzled.

Continuing with the reading list. These books were selected because I believe they are approachable by anyone. Reading these will not give you a complete design education, they will give you a good solid taste of the different parts of design:

100 Things Every Designer Needs to Know About People

Envisioning Information

About Face 3

#3 UXD -- User Experience Design

Finding the one image that describes how UxD thinks is tricky, so here are three (click on any for further detail):

User. Experience. Design. What do they care about? Well, you care about the whole damned thing. You care about the visual design; you care about the interaction design; but mostly what you care about is the experience of the user.

In my experience, the folks sporting the UxD title have nothing like a degree in UxD. It's a title they've adopted over the years because they know what I know: the title of designer is too general to be useful. Graphic designer and interaction designer are too specific. The user experience designer likely had an acronym in her past, but somewhere in the journey she decided it was to her advantage to care about the whole damned product.

Awesome.

There are a pile of design disciplines that contribute their acronyms and abilities to product design efforts and there is a time and place for each. The reason I seek the person that labels or thinks of herself as UxD is because I'm looking for a person who is willing to step up and be accountable for the entire experience.

The last part of the reading list includes absolute design classics. Yes, a book about comics:

The Elements of Typographic Style

The Design of Everyday Things

Understanding Comics

Party. More. Together.

Usability as a design discipline is conspicuously missing from this list. Thing is, even if it had a clever acronym I wouldn't include it.

Prior to Steve Jobs' return to Apple, there was a decent centralized usability team equipped with those fancy rooms with one-way mirrors and video cameras. I'm certain these folks did significant work, but when Jobs returned, he shut it down and he cast the design teams to the wind. Each product team inherited part of the former usability team.

Now, I arrived after this reorganization occurred, so I don't know the actual reasoning, but I do know I never saw those usability labs used once and I would argue that in the past decade Apple has created some of the most usable products out there. My opinion is that the choice to spread the usability design function across the engineering team was intended to send a clear message: engineer and designer need to party more... together.

I can't imagine building a team responsible for consumer products where engineers and designers weren't constantly meddling in each other's business. Yes, they often argue from completely opposite sides of the brain. Yes, it is often a battle of art and science, but engineering and design want exactly the same thing. They want the intense satisfaction of knowing they successfully built something that matters.

A design-centered culture is at throwaway empty phrase unless everyone responsible for the culture of design is in each other's faces. Titles and acronyms give you a starting point for understanding what a person might do, but what really matters is the respect that comes when you take the time to understand how they build what they love.

December 22, 2011

2011 in Review

Over a half a million unique visitors stumbled on Rands this year and as the year winds down, I wanted to take a look back at the year in articles. These are articles that turned out to be popular or just pieces I loved to write:

Bored People Quit. From a traffic perspective, the clear winner for 2011. This is article is a good example of a piece where I've no idea how it will resonate until I hit the publish button. There are articles I feel have a good chance before they are published: they target a specific group and cover a topic I think will appeal to that demographic. This was not one of them.

The Rands Test. However, this was. This homage to The Joel Test is actually a collection of threads teased out from the entire archive. This gave the piece a chance to resonate. Finding the precise number of relevant questions and points was the tricky part of this piece. Yes, the math is fuzzy - it's actually quite hard to get 12 points.

You Are Underestimating the Future. Most articles stew in a Dropbox folder for weeks. This article was written in an hour, straight out of my head, the day Steve Jobs passed away.. Another notable: titles normally mutate a few times as a piece is being written and rewritten. This piece started and finished with exactly the same title.

Fred Hates It. Any time I get to disassemble a part of conventional business wisdom, I am content. Taking apart and rebuilding off-sites was payback for every off-site that wasted days of my time. I also liked the Fred character that was built around the piece. He was not central to early drafts, he just showed up -- yelling. I couldn't ignore him, so he got the title.

A Bag of Holding. Writing obsessive research-based articles about things you love feels like a guilty pleasure. As I wrote in the newsletter, these pieces seem to just get longer and longer and I briefly worry that I'll lose the audience. Reading the comments on the piece is a good reminder that obsession loves company.

Lastly, there are still charity shirts available. If you're reading this, there's a good chance you like reading, so why not share that love with someone less fortunate this holiday season.

I'm thankful for all of you who showed up in 2011 and wish you a spectacular 2012.

Happy Holidays.

December 4, 2011

A Bag of Holding

The fundamental goal I have for a wallet via its design is that it prevents me from randomly collecting crap.

Years of folding leather wallets with myriad pockets and flaps all yielded precisely the same result: a Costanza-sized monstrosity that contained random crap that at one time I thought I needed, but eventually became useless clutter. This collection sat in my back pocket as a constant reminder of a tidying task I never did. Meanwhile, the massive collection of clutter ultimately destroys the wallet because no wallet is designed to perpetually hold everything.

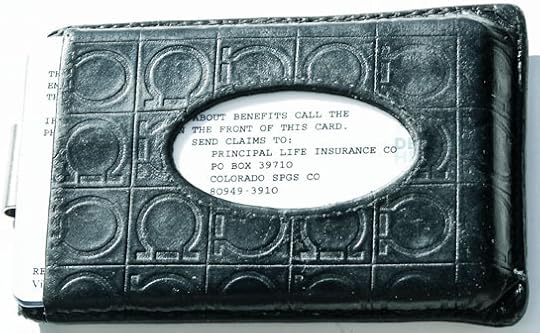

The current wallet is perfect.

It's perfect because:

There are zero moving parts. Whether it's a flap or a mechanical money clip, moving parts fail.

There is limited capacity. The card sleeve barely allows me to hold eight card-shaped objects. Eight. This means that each time I attempt to keep a receipt I think I'll need I have to fold it and slide it into the money clip. This means each time I handle my cash, I have to make a critical decision about the receipt -- do I still need it? You'd be surprised by the half-life of items in your back pocket that you recently thought were important when you're forced to look at them an hour later.

I'm not constantly stressing the architecture of the wallet attempting to contain everything. The current wallet has already lasted 4x as long as its predecessor.

It's with this wallet design win that I embarked on a quest for comparable bag.

The Bag Requirements

My requirements for a bag start with those of the wallet, but with an important essential addition: my bag has multiple use cases. My bag needs to adapt to whatever journey I'm currently on, whether it's a trip to work; a trip far, far away; or a trip where I'm sleeping in the dirt under the stars. A trip is either work or play, and since I work a lot more than I play, I chose to focus on work scenarios for my bag research.

I've heavily used two different types of bags over the past five years, and each has some win. To understand my initial requirements for a good bag, let's quickly look at each.

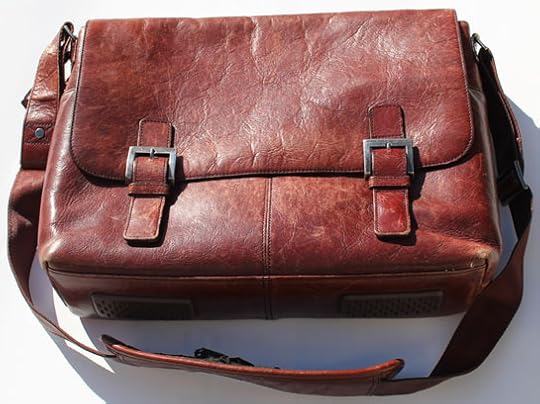

A Christmas present, this Johnson & Murphy messenger bag was the first work bag I loved. I find it gorgeous. A large, comfortable shoulder strap and decent space made this my go-to bag for years. All that was missing was the addition of a Incase sleeve to give my MacBook a little cushioning and I was set.

In the past few years I began to travel more, and the travel exposed a core weakness: the bag doesn't scale to far, far away. I found myself stuffing, shoving, and reorganizing headphones and power supplies in the bag, and while the magnet clasp works fine for a trip to work, when the bag is at capacity, it feels like it might pop open at any moment. I had a similar over the shoulder Tumi bag that was my workhorse for far, far away, but after sitting in a lot of airports, I'd seen a new development. Folks were wearing backpacks again.

I'm scarred by backpacks. My memory of backpacks was of these massive canvas-like bags full of immense and dense text books, crumbled paper, and a distinct smell of partially rotten peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. I remember constantly losing important papers in what was the seemingly infinite space contained within my bag, and I wasn't interested in returning to that frustration.

However, after countless hours watching travelers sport backpacks, it was time to get past my scarring and give backpacks another try. Tom Bihn's Smart Alec backpack was a chance to test this development.

After six months of steady use of my Bihn backpack, not only do I understand why people love them, I also better understand the complete set of questions and requirements I have for a good bag.

Does this bag make me look like a nerd? (Because I am.)

Bag religion is rampant. The only thing I'm looking forward to more than finishing this article is the crazy, foaming at the mouth bag nuts that are going to comment on this piece. My research is far less complete than in prior obsessive excursions, so bring it. I want to hear it. I've seen a lot of different bags, and my first requirement is that while I need my bag to be nerd-compliant, I don't want it to scream "nerd". This was part of my love affair with my messenger bag. It looked like I was part of the Pony Express when I was actually just a nerd hoofing my nerd crap hither and yon.

My bag needs to walk a delicate line between form and function. I need it to elegantly contain my various nerd crap, but I don't need to broadcast to the world that, yes, not only am I sporting my nerd gear, I also have a back-up of the aforementioned gear because I've built in redundancy. That's how I roll. I'm a nerd.

The messenger bag is a slight winner in this very subjective category. While the Smart Alec avoids most design disasters that remind me of JanSport-esque high school backpack monstrosities (straps, zippers, every kind of fabric everywhere, minimal pockets, and the color taupe), it makes less of a statement. It's slightly more function than form. However, it is a better answer to the question...

Am I going to beat you through the security line?

The hands down collective best measure for any bag is its relationship to your situation in the security line at the airport. Let's start with my mindset when I'm standing in line at security. I'm furious. Everyone's furious. While we suspect the security line is essential, as we stand in that endless line, we know -- we're absolutely sure -- there is a better way.

I'm fuming with this frustration when I finally get to the front of the line, but more importantly, I want to prove a point: I will now demonstrate to everyone the value of efficiency. Grab two trays, slip shoes off and put them in tray #1. Stuff wallet, iPhone, and boarding pass in shoes, belt off -- NEXT TRAY -- MacBook Air in second tray. Bag behind second tray, luggage behind that. And done. Why yes, I can do this and move the trays at the same time -- WHY CAN'T YOU?

No where in the above process did you see "futzing with my bag and looking for shit". In times of stress, a good bag demonstrates a couple of essential design points:

Easy access to the items I commonly need. This means my computer is a single zipper away, but this ease of access does not mean the safety of these essentials is compromised. The Smart Alec is a clear winner here. In addition to the main compartment, there are two external side pockets that are large enough to hold the answers to most travel questions.

Simply amazing zippers. My messenger bag has a magnet clasp and that works, but when I'm moving quickly, I'm wondering when this bag held together with a magnet is going to explode. When I close any pocket on my bag, I want to be left with the clear impression that the pocket is seriously closed.

A minimum of crap hanging from the bag. Each strap is an opportunity to snag myself on a random piece of crap that I didn't happen to see at the least opportune time. Traditional backpacks are the worst offenders when it comes to these straps. The designers seem to think I'm always mere seconds away from base jumping off a bridge where I need my backpack affixed to me in seven different ways. I don't. I need two straps. That's it.

However, I do want to know...

Can I go ninja?

The rule is: the further you are from your cave, there's the exponential increase in the chance something will go wrong at the least opportune time. The best example of this is standing in front of 1,000 people who are expecting you to smoothly and expertly talk for the next hour and you've just discovered your MacBook doesn't connect to the venue's projector.

In my bag, I'm certain I have video connectors for most projectors on the planet. Furthermore, I have a universal power converter, a power supply, two presentation remotes, and sundry other essential white cables. All of these items are expertly collected in what Tom Bihn calls a Snake Charmer bag. This mesh bag is not only of a size that it can handle all of these items, it takes oddly shaped items such as power supplies and Jamboxes and molds them into an easily transportable rectangle that fits inside of my bag.

To allow for ninja-like moves, a good bag is designed to maintain state, which means:

There is a knowable set of intelligently aligned pockets of a size and shape that make sense. This is where my messenger bag fails. In order to maintain that Pony Express feel, the messenger bag design assumes that everything I'm going to lug about is roughly shaped like a stack of 8.5x11 paper. While the MacBook and the iPad are paper-shaped, I have essential items that aren't square: delicate sunglasses, clumps of pens, and bizarrely shaped collapsible headphones. When I attempt to gear up for the long trip, it's clear from the resulting lumpiness that the messenger bag was designed for a pleasing form and not useful function.

The Smart Alec backpack not only has a sensible number of pockets, they are of a size that accounts for the fact that oddly shaped items follow me on my travels. More importantly...

In time of stress, the items are readily accessible, remain safe, and don't shift around. I can't predict when I need to go ninja. I don't know when it's absolutely essential that I have a pen ready to go in five seconds. When this moment does arrive, I don't want to be digging feverishly around my bag, placing various items on the floor as I search the bottom of the bag where the small stuff has fallen. The Smart Alec backpack not only has a sensible number of pockets, they are readily accessible and not cavernous. At this moment I can tell you: right side external pocket is notebooks and the essential small crap bag (which I'll explain in a moment), left external pocket is pens, mints, and playing cards, and the internal top pocket is safe and easily accessible for sunglasses, random small pieces of paper, a passport, and the occasional stash of hard candy.

All my stuff, readily accessibly at a moment's notice -- that's pretty ninja. Still...

Is my bag smarter than I am?

Everything is exponentially and unnecessarily harder when you're stressed, and it's in these moments that you appreciate the design of a good bag. A well-maintained state allows me to go ninja, but knowing precisely where my stuff is safely located is just the first step. A well-designed bag is thinking for you when the last thing you're doing is thinking. Some examples:

Sub-bags. In addition to intelligent pocket size and positioning, Bihn pushes an idea to help me maintain state: sub-bags. For everyday trips, I have a single sub-bag that I'll call "essential small crap". Everything I'd normally lose or constantly be untangling is in a small bag that is transparent on one side, and which sits well contained precisely in the same pocket.

An unexpected sense of space. This is a direct contradiction to my requirement that my bag prevents me from randomly collecting crap, but part of being ninja is the need to scale. I will randomly need to lug around a randomly shaped something from here to there and my preference is that my bag does this without fuss. The messenger bag fails here, especially on longer trips. I'm at max capacity on a long trip, which means I'm shoving newly acquired items in coat pockets or onto fellow travelers. As for the Smart Alec bag, I never felt I've filled it. Sure, I can lug your randomly shaped something... anywhere.

Agility. My agility test is relatively simple: how many people are impacted/aware when I attempt to retrieve my MacBook while sitting in the middle seat? Any answer higher than one is too many. For the messenger bag, I first need to find the handle, which, given how it was shoved under the seat in front of me, is trickier than it needs to be. Then, I slide the bag out, lift the flap, unzip the Incase, and slide out the hardware. If you're sitting on either side of me, you're going to be well aware of this process because of my odd elbow gyrations.

The backpack is shaped like a bullet. You slide the base easily under the seat in front of you, leaving the tip pointed directly at your feet. When I need something, the handle is at the tip of my toes, the zipper is easy to grab and works every time, and the Brain Cell holding the MacBook is right there. If you're sitting next to me you'll end up wondering, "When did he pull his computer out?" Whether it's shoved into an overhead compartment, slid under a seat, or thrown in the back of a taxi, my bag needs to remain accessible and useful. This means I can get to it, and once I get to it, I can perform whatever action I intend without annoying every single person around me.

Full range of motion. The defining aspects of a backpack are its most obvious -- it's on your back. After many years of single-strap messenger bags, I was shocked when I moved to the backpack and suddenly had two hands. A messenger bag does not full occupy one of your arms, but your shoulder is in a constant balancing dance with the bag to make sure it's in the right place. With a backpack, this is a non-issue. When it's on your back it's gone and you've got a full range of two-handed ninja motion.

Through its design, a good bag makes me look smarter by giving me deft answers to most travel disasters, but I have one more request.

Can I take a bullet? Do I look good after I've taken a bullet?

As my bag accompanies me everywhere on the Planet Earth, it's apt to encounter small random disasters. Briefly dragged on the asphalt, being drenched by half a cup of airplane coffee, or being unceremoniously thrown in the back of a cab. When these micro-disasters are going down, I need two things of my bag:

Everything in it needs to admirably survive and generally remain in the same location, and,

The disaster results in the bag acquiring additional character.

Sturdy is the word you're thinking. Good solid craftsmanship. Yes, this is all true, but the art lies in building a bag that doesn't look tired after the unexpected has occurred -- the bag needs to look like it's lived.

The messenger bag is a solid winner here. The bag has had the shit kicked out it, but it doesn't look like it's beaten, it looks worldly. The Bihn bag is well constructed out of impressive sounding materials such as ballistic nylon. It looks sturdy, it looks like it can take a bullet, but once the damage is done, I don't know what story the damage will tell.

Efficient Disaster Management

When I stand up to go somewhere, the routine is precise. Right pocket, wallet. Left pocket, iPhone. Keys in hand, grab my bag and go. It's this sort of workflow precision that allows me to stay cool when the unexpected occurs. My inner dialog during the situation is, Well, see, I've got my shit together, so even though this unpredictable thing is going down, I'm doing my part to support predictability.

Whether it's a wallet or a bag, its design needs to encourage and support my irrational worldview that with the proper level of organization those disasters, large and small, are all manageable.

November 13, 2011

How Can I Help You?

Being computer literate means getting asked to help. I'm happy to help. I believe the less you fear your computer, phone, or tablet, the more you'll get out of it, so, absolutely, How I can help you?

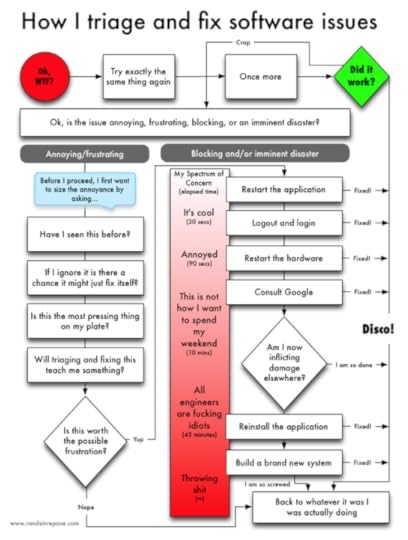

However, this free tech support does come at a cost. I have a system for evaluating a problem which is accompanied by colorful inner monologue. The following flowchart explains both the details of how I triage a problem, how I might fix it, and how and why I'm likely to swear while I'm helping.

Download the larger version.

November 6, 2011

Why?

Early in the design discussion for the logo for the latest Rands in Repose charity t-shirt, Robert Padbury responded to my early design feedback: "You know, I realized something when I was thinking about this the other day - People don't really have more than the following three responses to a design:

It's awesome.

It sucks.

Apathy."

This short list of responses captured me with their lack of subtlety. Three bullets effectively describe the majority of opinions people have about topics that often deserve more consideration. While Robert's eventual point was different, his observation serves as a starting point for understanding why I'm once again offering a t-shirt supporting a literacy charity.

As with all other prior shirts, all of the profits go to First Book, a charity focused on promoting children's literacy. The reason I continue to choose this charity is simple: I think the more people take the time to read increases the likelihood that they can build a defensible opinion.

Having a defensible opinion takes work. There is infinite information out there and that means you need to pick and choose the topics where you want to stop and ask, "Wait... why?" I'll explain via a creepy story.

Back before there was a publicly available Internet, a doctor told my mother that smoking would keep the baby's birth weight down. Funny thing is, it's true. The unfunny thing is that low birth weight babies are at an increased risk for serious health problems and lasting disabilities. The decidedly unfunny thing remains -- it was her doctor who told my mother this "good news".

History is full of lies and ignorance propagated by people who've put their trust in the ideals of allegedly qualified others. Now, as we live in a world divided by opinions acquired via Twitter, it's never been easier grab onto a clever 140-character quip and assume it's the truth. The fires of ignorance burn wildly on these acts of intellectual laziness.

Having an opinion takes work. It means stopping in your tracks and staring conventional wisdom in the face and asking it to explain itself. It means drilling deeper than the conventionally polarizing opinions that a topic is simply awesome, it totally sucks, or it's completely irrelevant to you. Chances are, it's a little bit of all three, but that type of ambiguity is mentally exhausting, right? Can't we just love or hate? It's so much easier to yell when it's right versus wrong or us versus them.

Having an opinion means starting to explore in Wikipedia as a means of defining and refining your curiosity, but not trusting that it's true. It means researching and building an intellectual map around a question. It means having the confidence and the courage to open a book, find the facts, and working to build a complex and defensible opinion so you can personally answer the question: "Why?"

And I think it's a habit we want to encourage as early as possible.

The third version of the Rands charity shirt has a new purchase option. You can either purchase the lovely red shirt or the limited edition gun metal version, which also includes a set of customized Field Notes. The clingy bamboo stylings of previous shirts are gone and replaced with American Apparel's finest short-sleeve cotton t-shirt. Again, all proceeds of both shirts go to First Book.

I'd like to thank Robert Padbury and Jim Coudal for their generous donations to this effort. They are both awesome and now you know why.

October 23, 2011

The End

When I'm presenting to a large audience, I have three internal states:

"I'm screwed." I have not yet begun the presentation, but I'm imminently starting. This phase sucks. Every possible screw-up I've ever performed or could perform is running through my mind and my gut instinct is a sensible "just fucking run for it". This state does not end when I walk up on stage and begin talking. In fact, this phase doesn't end until...

"I'm really just glad that I don't appeared to be screwed." After a few minutes, after I've stepped through the introductory slides, gotten the audience to laugh once, and have a sense of the room, I pass into the second state, which is a presentation steady state. I'm still operating at very high nervous energy because I'm a nerd introvert standing in front of a room full of strangers, but I've had enough success that I believe I can make this presentation happen. My practice has paid off and this is the state I operate in until...

"The end." After all of the build-up of all potential screw-ups, plus my very high energy, and the multiple sleepless nights that led into this presentation, this final state used to show up with a calming sense of relief: "Whew, I'm like three slides away from escaping the firing squad. Didn't think I'd make it without taking a header off the back of the stage." I take a deep breath and then race towards the ending, and when I get there, I blast by it and stand there lamely wondering why everyone isn't clapping. The room is full of exactly four seconds of dead air. What happened?

Either the audience did not know I was at the end, or maybe they had no idea what I just said, or worse, they had no idea what was important.

The End of the Beginning

The sister studied communications in college, and one break she returned full of interesting points about the construction of movies. A point that stuck: a movie has a well-defined point when the beginning is over. The main character has been introduced, the dramatic premise has been established, the dramatic situation around the premise has been constructed, and with a single defining action, the scene changes, and you're done with the beginning.

Try it. Next time you're watching a movie, watch for when the beginning has ended. Be warned, once you start, it's hard to stop. It's been years since I learned about the endings of beginnings and I still compulsively measure for when the beginning has ended.

We spend a lot of time worrying about the importance of beginnings: first impressions, great opening lines, or the perfect handshake. The theory is that a huge amount of context regarding a person, place, situation, or thing just shows up in the first few seconds of interaction. I buy that because people like to believe they understand what is going on long before they do, and with experience, sometimes they actually do.

A good beginning grabs your attention. The great opener elegantly and simply explains why you should listen. The well-played handshake instantly physically connects you to a person. Any of these beginnings, well executed, focuses you on the task ahead of you and asks you to listen, but what have you actually learned? Nothing. All a good beginning does is open you up to possibility.

The bulk of learning comes in the middle of the story and there's a lot to be said for great middles. The middle is the bulk of the plot of your life, it's the meat of the conversation, and it explains the intent described by the beginning, but I don't think middles are easy to screw up. I think we're inclined to explain our agenda, but I think we're undervaluing the power of the ending.

Awkward Endings

You sit down for coffee at Philz with a co-worker. Your go-to beginning with co-workers is something lame and innocuous like, "How was the weekend?" It's a verbal handshake of a question intended to create a sense of familiarity. You have an agenda, he has an agenda, so you spend the middle wrangling through your agendas, making decisions, creating next steps.

Then, when the agendas are all done, there's a pause where each of you is clear that you're somewhere near the ending. Like the way I used to close a presentation, I finish these types of meetings with a hurried declaration of "cool". But inside of that "cool" I'm making some massive and incorrect assumptions, including:

The idea that every single thing important to me is at the front of your mind.

Every action we've agreed upon is clearly assigned and ready to go.

Everything that was a professional issue that arose between us during this time (unless otherwise flagged) is fully resolved.

"Cool" covers none of this. "Cool" is just another crap ending.

A good ending, whether it's a meeting, a presentation, or an article:

Introduces itself, invites the audiences to the stage, and acknowledges receipt.

Reminds everyone what was actually important.

Says one more thing.

An introduction, an invitation, an acknowledgement. Whether you're filming a movie, running a meeting, or writing a presentation, each is a story with a beginning, middle, and end. The first responsibility of the end is to remind everyone involved what parts of the story we're supposed to care about and you need to tell them when the ending has begun.

The introduction of the ending varies depending on the medium. In a presentation, I stop before my ending and count five alligators and pace. In those alligators, the audience wonders, however briefly, "Did he forget where he was? Did he lock up?" I didn't. I just wanted your attention before I told, "Everything important that just happened is about to happen again. Quickly."

With their attention in hand, you need to change perspective. What was the point of this speech, meeting, or article was yours -- now it needs to be theirs. A good ending is a selfless act where you put everything important squarely in the audience's lap. Whatever your point was, it's now their point, their lesson, their view of the story. The invitation is a question: "How can I make this theirs?"

Do you have a friend who sucks at goodbyes? You stand up, walk to the front of the bar, shake hands, and they walk off. You stand there with a strange emptiness, wondering, "Did anything we just talk about actually matter?" Of course it did. You've known them for years and they listen hard and they debate hard, so what happened? They suck at goodbyes, at endings. The last part of an ending is deceptively simple; it's the audience acknowledging, "Yes, we heard you". They clap (or they don't), they repeat the most important part, or they sit there, tilting their heads slightly to the left with a half-grin, and psychically project: "Yes, I understood what you just said." The act acknowledges receipt of the ending and you've got to ask for it.

A reminder. As I write, I find myself staring at the beginning of a lot of endings. I'm clearly at the ending because the last thing I said was the last thing I wanted to say and I'm now staring at nothing. The easiest trick in the book regarding the absence of an ending is to look at your beginning. It's likely been long enough for both you and your audience that a quick repeat of the beginning is just the thing to starting an ending, but it's just a start. You said some important things in the middle, too. How about synthesis of that, too? Yeah, that's looking good.

Ok, throw it away.

A pure repeat of the high points of the beginning and the middle is a total cop-out. You need to find a different way to say the same thing. It's a different story, a slightly different perspective. Sure, you can use the same pictures or bullet points, but the words that you use need to be different. What you really need is...

One more thing. The beauty of a good ending is that you can't find it until you've written, spoken, or built a good part of your beginning and middle. For me, that's the high in building a thing -- the moment of clarity when you're hopelessly lost somewhere in the middle and you suddenly discover the slide, the paragraph, or the design that immediately and simply encompasses everything you've just been trying to say. You need to save that discovery for the end.

Endings Everywhere

The ending compliments the size and type of story. If you're drunk with Paul in the bar, the ending is small and it's social. I'm shaking his hand... with both hands because we talked about some shit and while I won't remember any of it, I want us both to remember that we did. The email ending is written and deliberate. If I sign this 'Sincerely', I will obliterate everything important I just wrote. So, I will choose "In related news, you rule..." The meeting ending is more formal. The action items aren't world changing, but your ending, the reminder that we actually love working here, explains to everyone that there is no crap work when you're doing what you love.

If your ending feels empty, perhaps you haven't said anything. Perhaps you have no story to tell or perhaps you don't what what that story is, yet. If your ending is full, if your ending is an invitation to remember what's clearly important, and if your ending leaves them with just a little extra, you've succeeded, it's a story told.

One more thing. Remember, they never remember the beginning. They only remember how it ended.

October 11, 2011

The Rands Test

It's hard to pick a single best work by Joel Spolsky, but if I was forced to, I'd pick The Joel Test. It's his own, highly irresponsible, sloppy test to rate the quality of software, and when anyone asks me what is wrong with their team I usually start by pointing the questioner at the test. Start here.

It's a test with 12 points and as Joel says, "A score of 12 is perfect, 11 is tolerable, but a 10 or lower and you've got serious problems". More important than the points, his test clearly documents what I consider to be healthy aspects of an engineering team, but there are other points to be made. So it is completely an homage to Joel that I offer The Rands Test.

I was employee #20 at the first start-up and the first engineering lead. Over the course of two years, the team and the company exploded to close to 200 employees. This is when I discovered that growing rapidly teaches you one thing well: how communication continually finds new and interesting ways to break down. The core issue being the folks who've been around longer who also tend to have more responsibility. As far as they're concerned, the ways they organically communicated before will remain as efficient and simple each time the group doubles in size.

They don't. A growing group needs to continually invest in new ways to figure out what it is collectively thinking so anyone anywhere can answer the question: "What the hell is going on?" This is the first question The Rands Test answers. As I'll explain shortly, the second question The Rands Test helps you answer is selfish. The second asks: "Where am I?"

12 Points

Let's start with bare bones versions of the questions and then I'll explain each one.

Do you have a 1:1?

Do you have a team meeting?

Do you have status reports?

Can you say No to your boss?

Can you explain the strategy of the company to stranger?

Can you explain the current state of business?

Does the guy/gal in charge regularly stand up in front of everyone and tell you what he/she is thinking? Are you buying it?

Do you know what you want to do next? Does your boss?

Do you have time to be strategic?

Are you actively killing the Grapevine?

(Note: While I'll explain each point from the perspective of a leader or manager, these questions and their explanations apply equally to individuals.)

Do you have a consistent 1:1 where you talk about topics other than status? (+1)

I think you'd be hard pressed to find anyone who would suggest 1:1s are a bad idea, but the 1:1 is usually the first meeting that gets rescheduled when it hits the fan. I'm of the opinion that when it hits the fan, the last thing you want to do is reschedule 1:1 time with the folks who are likely either responsible for it hitting the fan and/or are the most qualified to figure out how to prevent future fan hittage.

Furthermore, as I wrote about in The Update, The Vent, and The Disaster, conveyance of status is not the point of a 1:1; the point is to have a conversation about something of substance. Status can be an introduction, status can frame the conversation, but status is not the point. A healthy 1:1 needs to be strategic, not a rehashing of tactics and status that can easily be found elsewhere.

A 1:1 is a weekly investment in the individuals that make up your team. If you're irregularly doing 1:1s or not making them valuable conversations, all you're doing is reinforcing the myth that managers are out of touch.

Do you have a consistent team meeting? (+1)

The team meeting has all the requirements of the 1:1 -- consistency and a focus on topics of substance -- but don't give yourself a point just yet.

Status does have a bigger role in a team meeting. As we'll talk about shortly, the Grapevine is a powerful beast and a team meeting is a chance to kill it. I have a standing agenda item for all team meetings that reads "gossip, rumors, and lies" and when we hit that agenda item, it's a chance for everyone on the team to figure out what is the truth and what is a lie.

After that's done, my next measure of a team meeting is: did we make tangible progress on something? I don't know what you build, so I don't know what's broken on your team, but I do know that something is broken and a team meeting is a great place to not only identify the brokenness, but also to start to discuss how to fix it.

If you're killing lies and fixing what's broken in a team meeting, give yourself a point.

Are handwritten status reports delivered weekly via email? (-1)

If so, you lose a point. This checklist is partly about evaluating how information moves around the company and this item is the second one that can actually remove points from your score. Why do I hate status so much? I don't hate status; I hate status reports.

My belief is that email-based status reports are one of the clearest and best signs of managerial incompetence and laziness. There are always compelling reasons why you need to generate these weekly emails. We're big enough that we need to cross-pollinate. It's just 15 minutes of your time.

Bullshit. The presence of rigid, email-based status reports comes down to control, a lack of imagination, and a lack of trust in the organization.

I want you to count the number of collaboration tools you use on a daily basis to do your job -- not including email. If you're a software engineer, I'm guessing it's a combination of version control, bug tracking, wikis, CRM, and/or project management software. All of these tools already automatically generate a significant amount of status regarding what has tactically gone down each week.

When someone asks for a status report, my first thought is: "I'm already generating piles of status on these various tools, why not just ask those?"

Well, there's a lot of noise in those tools. Well, write a report that takes out the noise -- collaboration tools are built around reporting. The status information is out there. In what managerial textbook does it say it's a good idea to "Distribute the task of figuring out what is going on to the people who are performing the work?" That's, like, your job.

Well, what I really want is your high level assessment of the week. Three things that are working, three things that aren't, and what we're going to do about it. Ok, now we're talking. I can do a strategic assessment of the week, but why don't we just put that at the beginning of the 1:1? That way when you have questions (and you will), we can have a big fat debate.

But I'd like to have a record I can review later. Super, feel free to write down anything we talk about.

Yes, status reports are a hot button for me. I've written hundreds of them and each time I've begun one, I start by thinking, "Why in the world do I feel like I'm performing an unnecessary act?" Status reports usually show up because a distant executive feels out of touch with part of his or her organization and they believe getting everyone to efficiently document their week is going to help. It doesn't. Emailed status reports say one thing to 90% of the people who wrote them: "You don't value my time". This leads us to our next point...

Are you comfortable saying NO to your boss? (+1)

Perhaps a better way to phrase this point is: do you feel your 1:1 with your boss is somehow different than every other meeting you have during the week? Part of healthy communication structure is when information moves easily around the team, organization, and company, and if you walk into a meeting with your boss always on your best behavior and unwilling to speak your mind I say something is broken.

Yes, he or she is your boss and that means they write your annual review and can affect the trajectory of your career, but when they open their mouth and say something truly and legitimately stupid, your contractual obligation as a shareholder of the company is to raise your hand and say, "That's stupid. Here's why..."

Easier said than done, Rands.

Ok, don't say it's stupid.

Here's the deal. I believe that leaders who think they're infallible slowly go insane with power created by the lie that being wrong is a sign of weakness. I screw up -- likely regularly -- and I've been doing various forms of this gig for twenty years. While it still stings when I stumble upon or others point out my screw-ups, I'd sooner I admit I fucked up, because then I can figure out what I really did wrong faster, and that starts with someone saying "No".

Can you explain the strategy of your company to a stranger? (+1)

Moving away from communications, this point is about strategy and context. If I was to walk up to you in a bar and ask what your company did, could you easily and clearly explain the strategy?

This is the first point that demonstrates whether you have a clear map of the company in your head, and you might be underestimating the value of this map. If you're a leadership type, chances are you can draw this map easily. If you're an individual, you might think this map is someone else's responsibility and you'd be partially correct: it is someone else's job to define the map, but it's entirely your responsibility to understand it so you can measure it.

As we'll see with the following questions, The Rands Test isn't just about understanding communications, it's about understanding context and strategy. How do you think the employees of HP and Netflix feel given the strategy flip-flops over the past few months? Safe or suspicious? Let's keep going...

Can you tell me with some accuracy the state of the business? (Or could you go to someone / somewhere and figure it out right now?) (+1)

It's a brutal exaggeration, but I think you should independently judge your company the same way that Wall Street does: your company is either growing or dying. Have you ever watched the stock price of a publicly traded company the day after they announce that they are going to miss their earnings numbers? More often than not, no matter what spin the executives have, the stock is hammered. It's irrational, but what I infer when I see this happen is that Wall Street believes the company has begun a death cycle. If the executives can't successfully predict the state of their business, something is wrong.

I realize this isn't fair and there are myriad factors that contribute to the health of the business every single day, and I encourage you to research and understand as many of those as possible. But when you're done, I'd also like you to have a defensible opinion regarding the state of the business, or at least a set of others whose opinion you trust.

This is a picture that you are constantly building, and this is an easier task if you've given yourself a point on the prior question regarding company strategy. If you have a map of what the company intends to do, it's easier to understand whether or not it's doing it. This leads us to...

Is there a regular meeting where the guy/gal in charge gets up in front of everyone and tells you what he/she is thinking? (+1) And are you buying it? (+1)

Our last point regarding context involves the person in charge. In rapidly growing teams and companies there's a lot going on -- every single day. When the team was small, the distribution of information was easy and low cost because everyone was within shouting distance. At size, this communication becomes more costly at the edges. Directors, leads, and managers -- these folks tend to stay close to current events because it's increasingly their job, but it's also their job to take steps to keep the information flowing, and it starts with the CEO.

On a regular basis, does your CEO stand up and give you his impressions of what the hell is going on? Whether it's 10 or 10,000 of you, this is an essential meeting that:

Gives everyone access to the CEO.

Allows him/her to explain their vision for the company.

Hopefully allows anyone to stand up and ask a question.

If the value of this meeting isn't immediately obvious to you, I'd suggest that you are one of those lucky people who already has a good map of the company as well as a sense of the state of the business. That's awesome -- here's a bonus point for you: does the CEO's version of the truth match yours or is he/she in a high Earth orbit with little clue what is actually going on? Give yourself a point if it's the former and if it's the latter, what does that say about the state of the business? Growing or dying?

Can you explain your career trajectory? (+1) [Bonus: Can your boss? (+1)]

Next, switching gears a bit, give yourself a point if you -- right this very moment -- can tell me your next move. You're already doing something, so explain what you're going to do next. It's a simple statement, not a grand plan. One day, I'd like to lead a team.

Part of a healthy organization isn't just that information is freely moving around; it's what the folks receiving and retransmitting it are doing with it. You're going to mentally file and ignore a majority of this information, but every so often a piece of information will come up in a 1:1, a meeting, or a random hallway conversation, and it will be strategically immediately useful for you to know what you want to do next.

Angela got a promotion and her team is great and I've always wanted to be a manager.

Jan just opened a requisition and his group is working on technology I need to learn.

They fired Frank. That creates a very interesting power vacuum...

You can argue that even without a plan you'd make the same opportunistic leap, but I've found that having a map is usually a better way of getting to a destination.

There's a bonus point here as well. Does your boss know what you want to do next? He or she likely has even more access to the information moving around the company, and whether they like it or not, have equal responsibility to figure out how to get you from here to there.

Do you have well-defined and protected time to be strategic? (+1)

If you gave yourself two points on the prior question, congratulations, I think you're in better shape than most, but there's one more point. Are you making progress towards this goal? Can you point to time on your calendar or even just in your head where you are growing towards your goal?

I like being busy. Like really busy. Like getting in, grabbing a cup of coffee, and suddenly finding the coffee is cold, it's 6pm, and I forgot to eat busy. Busy feels great, but busy is usually tactical and not strategic. This is why I'm constantly maintaining my Trickle List -- it's my daily reminder of doing work that is larger than right now.

If you have time where you're investing in yourself while you're at work and your boss is cool with it -- give yourself a point.

Are you actively killing the Grapevine? (+1)

When Grace walks in your office, you know she knows something by the look on her face. She moves to the corner of the office and starts with, "Did you hear...?" and the story continues. It's a doozy, full of corporate and political intrigue, resulting in your inevitable response: "No. Way."

Being part of a secret feels powerful. In a moment the organization reveals a previously hidden part of itself, and in that moment you feel you can see more of the game board. So, that's why they fired him. I was wondering. Grace finishes with the familiar, "Don't tell anyone," which is ironic since that's precisely what was asked of her 15 minutes ago.

There is absolutely no way you're going to prevent folks from randomly talking to each other about every bright and shiny thing that's going on in your company. In fact, you want to encourage it. 1:1s and meetings are only going to get you so far. The thing you can change is the quality of the information that's wandering the company.

In the absence of information, people make shit up. Worse, if they at all feel threatened they make shit up that amplifies their worst fears. This is where those absolutely crazy rumors come from. See, Kristof is worried about losing his job so he's making up crazy conspiracy theories that explain why THE MAN IS OUT TO GET HIM.

Without active prevention, the Grapevine can be stronger than any individual. While you can't kill the Grapevine, you can dubiously stare at it when it shows up on your doorstep and simply ask the person delivering it, "Do you actually believe this nonsense? Do you believe the person who fed you this trash?" Rumors hate to justify themselves, so give yourself a point if you make it a point to kill gossip.

Magnitude and Direction

There is a higher order goal at the intersection of the two questions The Rands Test intends to answer: Where am I? and What the hell is going on? While understanding the answers to these questions will give you a good idea about the communication health of your company, the higher order goal is selfish. I'll explain.

I think of the two lines of questions as a vector. A simple vector can be drawn as two points connected by an arrow, but a vector is far more interesting. It's a geometric object that describes both direction and magnitude. Understanding how information moves, how you communicate with your boss, and being able to describe both your career strategy and that of your company sketches a vector in your head. The first point is you at this very moment and the other point is where you want to be. The distance and direction between the two start to explain how you're going to get there. I love vectors because they draw a picture about a complex problem and I hope as you were answering the questions above this mental picture began to appear in your head.

Like the Joel Test, the point of the Rands Test is not the absolute score, but the score is good directional information. If you got a 12, I'd say you're in a rare group of people who have a clear picture of their company and where they fit in. Between 8 and 10, you are likely troublingly deficient in either communications, strategy, or your development - it depends where the points are missing. Less than 8 and I think you've got a couple of problems.

There are a lot of different scenarios I expect folks to find themselves in as they explore these questions, which is why it's tricky to proscribe specific action. Your company may be doing well, but you may be unhappy and have no clue what you want to do next. You might love your job, but have no idea whether the company is actually growing. Your course is dependent on what you care about and the Rands Test points out good places to start.

October 6, 2011

You Are Underestimating the Future

I do this talk called "The Engineer, The Designer, and The Dictator", and it's a talk about the things I love. It's a little bit about the nature of engineers and why I think we might have more power than we deserve. I talk about designers, the creators of art, and how I want the engineers and designers to party together more. Lastly, I talk about the importance of dictators -- forces of nature whose vision is terrifyingly clear and whom we willingly follow even though we're a little scared of them. I explain how a dictator mediates the battle between art and science with a curious mind, an iron fist, and taste.

Yeah, it's about Steve.

My first thought as I stared long and hard at Apple's home page yesterday wasn't a specific Steve story or one of his many insightful quotes. The thought was...

You are underestimating the future. You are fretting about the now; worrying about little things that don't matter. You are wasting precious energy obsessing over irrelevant details. You don't believe that a better future is out there and can be built, that it can exceed people's expectations, because you're spending so much time considering the truth of the present and the seemingly important lessons of the past.

You are underestimating the future because you believe you cannot see it, but you can - you've seen it done before.

My favorite video of Steve was shortly after his return to Apple. He wasn't CEO yet; he was still consulting and was speaking on the last day of 1997's WWDC. It wasn't a prepared speech; it was Q&A, an open microphone where anyone could apparently ask Steve Jobs anything. (Steve starts at 2:12)

I've watched this video a few times, and what consistently impressed me wasn't just his ability to elegantly answer random and sometimes hostile questions from an audience, it was the fact that it was abundantly clear what he wanted Apple to be. Again: 1997.

I was an Apple employee for eight and half years and I didn't see the video until after I'd left the company. For those who worked there and for those who have watched Apple's success, what resonates from this crackly old video is that it was clear that Steve could see the future. He may have given features, products, and strategies different names at the time, but so much of what Apple has become is described in a video from almost 14 years ago.

Steve didn't underestimate the future; he could see it, and, more importantly, he built it.

October 3, 2011

Building Serendipity

Blake looks tired. He's sitting in the food court at O'Hare Terminal 1. He's halfway through a beer and the jokes are coming out, but they're a little labored. Blake is tired.

Blake's tired because Blake goes to a lot of conferences. Earlier in the conversation, he was explaining the next month of travel and I lost track of the number of conferences he was attending somewhere between Peru and Brazil. I feel like I attend a decent number of conferences over the course of the year, but Blake's list quickly demonstrates that I'm a conference rookie.

Still, I know why Blake is tired.

That One Person

I have exactly one goal when I attend a conference. Through some bizarre and unpredictable sequence of events, I'm going to meet that one person I absolutely need to know. Who they are, what they're building, or what they've done -- it's mind-blowing shit that, once identified, forever alters my perspective. In hindsight, after each conference is complete, it's obvious who this person is because I can't stop fucking talking about them. Before the conference this person is a mystery and there is no reliable way to predict who they might be.

My evolving experiences with conferences over the past two decades both conveniently enable documenting the three types of conferences out there, as well as my strategy for building the possibility of serendipitously meeting that person who will rock my world.

The Everybody Conference

Comdex was my introduction to both conferences and Las Vegas. In my late teens, my Dad was making a tidy profit building clone PCs, and Comdex was the place to see the latest developers in the PC world. I remember when Bill Gates got up on stage and showed a new feature in Microsoft Word that allowed you to visually draw tables in a document. Times were simpler then.

The Everybody Conferences are defined by their hugeness. Present day WWDC, SXSW, and JavaOne are similar beasts where each and every one of the faithful gathers to drink deeply of the Kool-aid. The food sucks, presentation quality varies wildly, and you seem to constantly be in line, but everyone is there and how often do you get an opportunity to hang with everyone?

For me, the Everybody Conference is a stressful affair. I am uncomfortable in large crowds and standing in lines drives in me insane. However, I appreciate that both lines and crowds are significant opportunities for serendipity, so where's the middle ground?

I've refined the compromise strategy after many years at SXSW: find a conveniently located bar near where everyone is stumbling, invite two close friends and buy them a lot of booze, and then tell anyone who might care where you are. This event comfortably starts with just the three of you and becomes even more comfortable as the booze begins to flow. Serendipity is encouraged both by being in a public location where folks randomly show up as well as via your invite to those who might care.

At SXSW, I rarely attend sponsored events (lines), I rarely attend talks (panels? really?), and while I might wander the conference hallway a few times, my strategy of hiding in plain sight allows me to balance avoiding the hugeness while still encouraging serendipity.

The Specific Agenda Conference

The Specific Agenda conference is a smaller affair and has a specific theme, whether it is technology or audience. There is delightfully less pomp and circumstance with the Specific Agenda conference, but more importantly, there are fewer people. Whew.

A smaller conference is more palatable to me not only because the horde isn't there, but because the conference can be comprehended. I can get both the entire theme and audience in my head, which, as a nerd, gives me the illusion of predictability and knowability. However, the decrease in population size means more aggressive steps are necessary to encourage serendipity. I can't hide in a bar and tweet my location: I need to be proactive.

The strategy at the Specific Agenda Conference is: attend everything. After I've arrived, checked in, and am sitting in the hotel room reviewing the conference, I invariably find an event and think "lame". I still go. Yeah, I don't need a job, but I'll check out the job fair. Yeah, there's an awkward corporate speaker whose presentation is more advertising than content -- I go to that as well. I might walk out after three minutes, but I still show up because at a smaller conference I want to know the Story.

Because of its size, the Specific Agenda conference builds a discernible shared story. It starts when the keynote speaker is simply awful and you lean over to a stranger and ask, "Is he that bad?" In a moment, the stranger becomes slightly less strange when she nods, "Yes, he's really awful. And he's my boyfriend."

Oh.

There is now one less stranger at the conference and the first page of the Story, which is titled, "Wherein I make a new friend by ripping on their boyfriend's crap keynote" and it's a great story that everyone has a version of because they're all sitting there with their own experience of the horrific keynote.

By including myself in the majority of the Specific Agenda Conference, I see what everyone else sees, and we collectively build a Story that introduces and intertwines us. I can think back to every Specific Agenda conference and feel the Story that was built. There was that one in Montreal where at 2am we ended up in a line in subzero weather waiting to eat poutine. Yeah, I was in a line. You know why? Because I knew I was in the middle of a great Story and great Stories are great fodder for serendipity.

The Welcome to Our Home Conference

The final conference is just a variant of the Specific Agenda conference, but I'm calling it out because this conference is one built with serendipity in mind. To date, I've only attended two Welcome to Our Home conferences: Webstock (three times) and Funconf (twice).

This conference is what it's called: an invitation into someone's home. It has some technology, design, or open source theme of some sort, but that's just there to get your attention. The real intent of this conference is building serendipity, and they do in three increasingly important ways:

Quality of speakers. Each year, Wellington, New Zealand's Webstock shocks me with their speakers. Go look now. Yeah, you'd go for just half of those folks. Dublin, Ireland's Funconf is less forthcoming with their speakers, but that's because they sell out tickets simply on the strength of word-of-mouth from the first conference, which included a bevy of fascinating speakers.

The Venue. Webstock is held in Wellington's town hall, which looks like this:

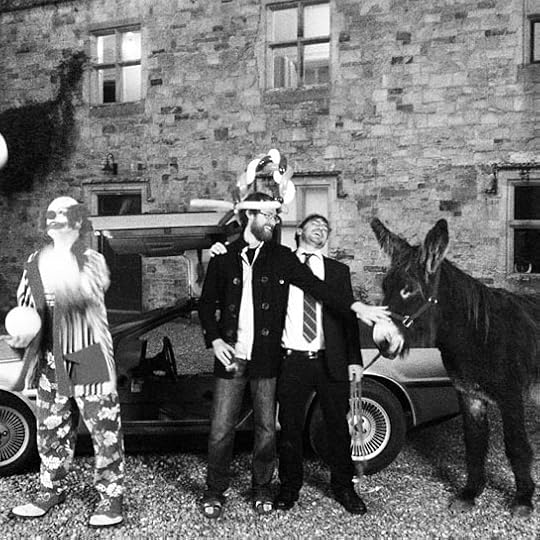

This Funconf was held in a castle and that looks like this:

The venues for both conferences go out of their way to make you feel like you're not at a conference, but rather hanging with your friends, well, in a castle. More on this aspect in a moment.

The Organizers. In my opinion, the defining characteristic of the Welcome to Our Home conference is the organizers. Whether it's Webstock's Natasha Lampard and Mike Brown or Funconf's Paul Campbell and Eamon Leonard, each conference is a reflection of the care of these organizers. I just returned from my second Funconf and I know that it was held in a castle because of Paul, and I know there was a clown, a DeLorean, a llama, and a donkey in the courtyard thanks to Eamon. You're right -- it doesn't make sense -- but that's because you weren't there and you weren't a part of the Story.

There is very little strategy in play when it comes to the conference. They tend to be small enough that I don't hide and there is rarely an event I'm not tripping over myself to attend. The Story builds itself with little effort on my part and there's serendipity everywhere.

Welcome to Our Home

I'm eating an awful ham and cheese sandwich and drinking a Sam Adams when I ask Blake what his favorite part of Funconf was, and he gives the same answer everybody does about any conference: "Well, it's the people, right?"

Blake knows what I know. Whether it's Everybody, A Specific Agenda, or A Home, a conference is defined by the people. And that's why I'm a little a jealous of Blake. I know why he's tired. He was up until 6am drinking with the CTO of Amazon in front of the fire... in a castle.

And that's a great story.

September 11, 2011

Fred Hates It

Management has a set of power words that it's appropriated as a means of giving it a sense of identity. This list is endless and entertaining. When these words are spoken, they are said in such a way that you are meant to wonder in awe, "What does that mean?" but you don't ask for fear of looking like an idiot.

Today's word: off-site. An off-site is a... meeting. There are some specific characteristics to an off-site, but all it is a meeting with a group of people that likely lives up to its name in that it's elsewhere, it's off-site.

Now that you understand what it is, let's understand why you might hate it.

Why I Get in Fred's Face

The reason an off-site exists is simple: you, the leader of the people, need certain essential work to occur that cannot easily occur now under normal conditions within the building. It's a little sad. When it was only 20 of you, each of three different off-sites I'm about to describe would just happen... organically. Fred would stand up in the middle of the office and say, "Ok, we need a new UI framework. I'm going to do it, and anyone who wants to get in my face needs to do it now."

So you got in Fred's face. You argued. You debated. Fez and Phil jumped in and in 17 very important minutes, you fundamentally changed the UI architecture of the product.

At an organizational size that varies for every team, natural cross-pollination and communication activities that used to happen organically, that allowed for cultural and strategic work to get done, and allowed for big decisions to be made, can no longer occur. The team can no longer look around the room and get a sense for how everyone is doing because there are too many everyones.

Zeitgeist has become diluted. Random hallway error correction doesn't happen because the right folks aren't bumping into each other. It's sad especially for the folks who vividly remember standing up and getting in Fred's face. You need to recreate the space and place where a team can bond, a strategy can be devised, or you can begin an epic journey.

You need a well designed off-site.

Who We Are, What We Need, and Our Epic Journey

The reason you invoke the off-site is going to vary from group to group. The following are three specific scenarios where I believe you need to employ the off-site, but there are more.

We need to understand who we are. If you're familiar with my writing, you'll know I don't think you really know what the hell is going on in a team for 90 days. You have moments of comforting clarity during the first three months, but you don't really know all the moving parts until a chunk of time has passed. Now, multiply that early confusion by every single person who has been hired in the last nine months.

During times of rapid growth, a team doesn't necessarily take the time to stop and get to know each other because they arrive and the first thing they notice is, "Whoa. Everyone is in a big fucking hurry, so I must hurry as well." Their normal instincts regarding getting to know those around them are buried in their goal of being recognized as a person who is also in a hurry.

You need an off-site not to solve a strategic product problem, but to give the team time away from their hurry to get to know each other. Socialization will happen via each of the off-sites I'm about to describe, but the need for a team to understand itself is a cause worthy of an off-site all by itself.

We need a new direction and/or we need fewer disasters. Something significant is broken. Either disasters are occurring and the normal processes of detection and correction aren't working, or everything appears to be working but we're not achieving success -- for whatever success means at that stage of the company. In either case, the status quo represents a legitimate threat to the company.