Michael Lopp's Blog, page 52

January 1, 2013

The Process Myth

On the list of ways to generate a guaranteed negative knee-jerk reaction from an engineer, I offer a single word: process.

Folks, in order to make sure that we hit our ship date, we have a new bug triage... process.

You've heard the groans and you've seen the rolling eyeballs and made the fair assumption that engineers are genetically predisposed to hate process. It's an incorrect assumption that doesn't add up. Engineers are creatures who appreciate structure, order and predictability, and the goal of a healthy process is to define structure so order is maintained and predictability is increased. The job of a software engineer is writing code, which is codified process.

So, what gives? Why the groaning?

Engineers don't hate process. They hate process that can't defend itself.

Don't Answer the Question

At Apple, there is a creature called an Engineering Program Manager ("EPM"). Their job is process enforcement. They are the folks who sat in meetings like bug reviews and made sure that every part of the process was being followed. As a person who prefers to spend mental cycles on the people and product rather than the process, I appreciated the role of the EPM.

A good EPM's job is to keep the trains on time by all reasonable means. However, my experience with program managers over the past two decades is that 70% of them are crap because while they are capable of keeping the trains running on time, they don't know why they're doing what they're doing. When someone on the team asked them to explain the reasoning behind the process, they'd say something to the effect of, "Well, this is how we've always done it..."

If you want to piss me off, if you want me to hugely discount your value, do this: when I ask you a clarifying question that affects how I will spend my time, my most valuable asset, don't answer the question. This non-answer is the root cause of an engineer's hatred of process. A tool that should help bring order to the universe is a blunt instrument that incites rage in the hands of the ignorant.

Healthy Process is Awesome

It pains me to type that heading because of the 70% out there who are giving process a bad reputation with their blind enforcement. But if we explore where process might come from, you'll understand three things: the circumstances that lead to the necessity of process, how it could be awesome, and most importantly, your role in maintaining the awesome.

With a small team, mostly you don't need process because everyone knows everything and everyone. You don't have to document how things occur because folks know how to get it done, and if they don't they know exactly the right person to ask. If something looks broken, you don't hesitate to stand up and say, "That's broken. Let's fix it." You do this because, as a small team, you feel equally responsible for the company because everyone is doing everything.

Hidden among all this work are essential parts of your company that everyone knows, but no one sees: your values and your culture. If you're a small team, you likely don't have a mission statement, you have the daily impossible amount of work you must do to survive and the way you do that work is an embodiment of your culture and your values.

Now, if you stopped someone in the hallway of this hypothetical company and asked them to explain the values, they'd look at you like a crazy person and give you exactly the same damning answer as the program manager above: "Well, this is how we've always done it." Double standard? No. The difference here is that if you could actually get the attention of the hallway person, if you pressed them, they'd be able to explain themselves. When you asked them, "Why must we debate every decision?" they'd say, "We encourage debate because we want to make the most informed possible decision."

Then, at some magical Dunbar number, you pass two interrelated inflection points. First, the number of new hires arriving exceeds your population's ability to organically infect culture and values. Second, because of the vast swath of preexisting people, the arriving individual erroneously believes that they as a single person can no longer influence the cultural course of the company. The team is fractured into two different groups that want exactly the same thing:

#1 The Old Guard. These are the folks who have been there for what seems like forever. They understand the culture and the values because they've been living and breathing them. They have a well-defined internal map of the different parts of the company that consist of the rest of the Old Guard. Whether they like it or not, they are the exemplars of what the company values.

#2 The New Guard. These folks have arrived in the last year and while they understand that there is culture and there are values out there, they spend a lot of time confused about these topics because no one has taken the time to sit them down and explain them and the folks who are qualified to do so are busy keeping the ship pointed in the right direction. This situation is exacerbated by the fact they don't have an internal map of the company in their head and they don't know who to ask what, so once their honeymoon period is over, they get angry because they don't know why they're doing what they're doing.

Problem is, the Old Guard can't conceive of a universe where everyone doesn't know everything, and they have difficulty explaining what they find obvious. The Old Guard begins to hear the New Guard's crankiness, but their suggestion is, "Duh, fix it. It's your company. That's what I did." This useless platitude only enrages the New Guard because while they desperately want to fix it - they don't know how - and having the Old Guard with their informed confidence and flippancy imply it's simple is maddening.

Eventually, meetings are convened, whiteboards are filled with suggestions, and while different companies give the end result different names, it's the same outcome: someone volunteers to document the means by which we get stuff done. They document the process.

When you think of process, I want you to think of this moment because it could be a noble moment. Process is being created not as means of control; it's being built as documentation of culture and values. It's likely you can't imagine this moment because you've been clubbed into submission understanding process as the dry documentation of how rather than the essential explanation of why.

The Dry Documentation of How

Here's some really boring process for you. It's an internal transfer process. Leads refer to it when someone wants to move from one group to the next. Chances are, you may even be aware this thing exists. Lucky bastard. Here's the breakdown:

Employees must have been in their current job for one year before applying for a new job.

Employees must have a performance rating of solid or higher in order to apply for a transfer.

An employee may have one conversation with a new job's hiring manager before discussing the internal transfer with their current hiring manager.

And it goes on, but you get the idea.

Who wrote this? HR prescriptive bullshit, right? Yeah, it probably was someone in HR that wrote this years before you arrived, but they were trying to help. When it was 42 of us, how did this internal transfer happen? Well, Frank wanted to try out design, so he talked with the design lead, Luke, who then talked with Frank's lead, Alex, over a beer and it was done in a week.

This informal conversational process doesn't work at 420 people for a lot of reasons: Frank doesn't know if there are opportunities in design because he doesn't know Luke. If he does figure out that there is a gig and has a chat, Larry doesn't even think to talk with Alex because they don't know each other. This leads to all sorts of misunderstandings and crankiness about who knows what, which leads to trust issues, crap communication, and politics that could have been all avoided if we simply agreed to document how our company felt about internal transfers.

I want you to look at this boring process from the perspective of someone who cares about preserving culture. What values are they attempting to capture? Look again.

Employees must be in their current job for one year before applying for a new job. We meet our commitments to our teams.

Employees must have a performance rating of solid or higher in order to apply for a transfer. If someone is failing at their job, we work to improve them rather than shuffling the problem elsewhere in the company. We fix problems, we don't ignore them.

An employee may have one conversation with a new job's hiring manager before discussing the internal transfer with their current hiring manager. We understand that situations change. We want people to grow, but we are adamantly transparent in our communications because we know that poor communications results in painful misunderstandings.

The unfortunate fact is that when an internal transfer policy does need to be defined, it often falls to an HR person who is good at defining process, but is shitty at explaining the culture. This means that as they diligently and capably do their job, they're also merrily eroding your communicated culture and values. Process should be written by those who are not only intimately experiencing the pain of a lack of process, but who are also experts in the culture.

Imagine all process as a means of capturing and documenting culture and values. Unfortunately, in a larger company, it doesn't work that way. Even if qualified cultural bellwethers took the time to document their pain and to write a process, these folks eventually leave. When they leave so does their cultural context, and the root pain that defined the process leaves with them. The company forgets the stories of how we ended up with all these bulleted lists, and when someone asks why, no one knows the story.

Defend Itself

An engineer instinctively asks why. When someone or something doesn't make sense to them, they raise their hand and say, "This feels inefficient. Explain this to me." Now, they don't usually ask that way. They usually ask in a snarky or rude fashion that gives the process enforcers rage, but snarkiness aside, the engineer is attempting to discover the truth behind the bulleted list.

Anyone who interacts with process has a choice. You can either blindly follow the bulleted lists or you can ask why. They're going to ignore you the first time you ask, the second time, too. The seventh time you will be labeled a troublemaker and you will run the risk of being uninvited to meetings, but I say keep asking why. Ask in a way that illuminates and doesn't accuse. Listen hard when they attempt to explain and bumble it a bit because maybe they only know a bit of the origin story.

It's a myth, but healthy process is awesome if it not only documents what we care about, but is willing to defend itself. It is required to stand up to scrutiny and when a process fails to do so, it must change.

Insist on understanding because a healthy process that can't defend itself is a sign that you've forgotten what you believe.

December 26, 2012

Six Years of Rands

I enabled Google Analytics on October 21, 2006, roughly a year after I started using Shaun Inman's real-time (yet infrequently updated) Mint software. Both packages are part of my daily routine to see what is going on with the site, but I've rarely used them for more than understanding the basics: How is this article tracking? Who is talking about it? More recently, I've started to use the Chartbeat package, a solid combination of what I get out of Mint and the real-time portion of Google Analytics.

With the quiet of the holiday season, I wanted to take a step back and analyze a question I've had for years: should I be writing less... more? I'm averaging around two articles a month and the trend is that the articles are getting longer and slightly less frequent. My question was: how was this trend affecting my traffic? Thanks to years of analytics and my obsessive nerd tendancies, I can start to consider these questions:

The following is a graph with two Y-axis: the left axis includes total page views, visits, and uniques. While I've obscured the detailed totals, for context, in 2012 I did ~ 1.2M page views. The right axis and the red bars represent the number of articles published in that year. Again, for context, this is the 20th piece published in 2012.

To my surprise, for the first four years I was keeping regular stats, my traffic was shrinking. I had no idea. At a glance, it looks like the trend downward is related to the number of articles, but in 2011, the traffic picked up even though I was still writing less. This trend continued in 2012 when I wrote the least amount in terms of number of articles, but had the best year in terms of traffic. Further investigation is warranted.

2007 was the debut of The Nerd Handbook and if there was ever an article that defined this site, it was this piece that explained to the significant others of nerds what the situation was with all the nerdery. A Glimpse and a Hook was in the sidebar for years (and only recently replaced by Bored People Quit) and stood out as practical and usable advice for your resume. (For the record, resumes are dead, we're just in denial) N.A.D.D., a piece I wrote in 2003, took the #3 spot in 2007 and is testimony to how much ongoing traffic you can garner with a single popular article. #4 was the debut of The Button continuing my "Looking for a new Gig" series. Finally, The Gel Dilemma, my obsessing about gel pens, took the #5 spot.

In 2008, a year I now see was a traffic down year, the top 3 pieces were articles I'd written the past year: The Nerd Handbook, Glimpse, and NADD represented 20% of page views in 2008. Two new articles broke the top 5: Out Loud was my first piece on developing presentations (and my love of Keynote). Horrible was my explanation of the futility of improving yourself where you were legitimately impaired.

In what will be a recurring theme, The Nerd Handbook returned in the #1 spot in 2009. It was a year where traffic losses appeared to stabilize. Glimpse returned in #2, but The Words You Wear was a new piece that continued my war against managementese. Gaming the System was my first foray into applying ideas of gamification into shipping software. The Maker of Things - a love note to the Brooklyn Bridge - was #5 on the year and remains one of my favorite pieces that I've written.

2010 was a down year. I haven't looked at the detail traffic stats as I type this, but based on history, I'd guess that the top 5 was dominated by existing pieces. Odd, I'm wrong. The Nerd Handbook remains in #1, but #2 was the arrival of a popular piece - How to Write a Book - which explained the final days writing Being Geek. At #3, The Update, the Vent, and Disaster documented my experiences with running 1:1s. Glimpse dropped to #4 and #5 was my treatise on How to Run a Meeting. What is unique about 2010 is the number of articles I wrote was down and you'd think that was why traffic was down, but, as you'll learn, you're wrong.

2011 was the first year since 2007 that the #1 spot was replaced. Bored People Quit garnered Nerd Handbook-type traffic. Nerd Handbook remained steady in the #2 spot followed by How to Write Book. You are Underestimating the Future was my goodbye note to Steve Jobs and grabbed the #4 spot which is impressive since it was written late in the year. Managing Nerds which I thought would be Nerd Handbook like, landed in the #5 - less impressive since it had all year to gather traffic.

Traffic wise, 2012 was my best year ever. Like 2010, I wrote 19 pieces (this is the 20th), but unlike 2010, the top 5 were dominated by new content. #1 - Someone is Coming to Eat You was a post-Steve Jobs piece regarding innovation followed by an exploration of hacking in Hacking is Important. #3 continued my innovation exploration in Innovation is a Fight with an analysis of the departure of Scott Forstall from Apple whereas #4 was a plea for folks to Please Learn To Write. #5 was A Design Primer for Engineers, again, the first piece of the year that I expected to fare better.

If you look at total traffic for the past six years, the articles you'd expect are the leaders. They're the ones in the right bar because they're the ones that continue to resonate and therein lies the answer to my question. The interesting aspect of traffic to me is to understand: was what I wrote valuable?

I scratch my link blog itch with Twitter, I share my travels with Instagram, but here - I continue to learn how to write.

Thank you for reading and Happy New Year.

December 9, 2012

How I Instagram

I remain steadfast in my belief that one of the best examples of the disproportionate value of the iPhone is the fact that we are able to completely ignore the fact that its form factor is horrible to use as a camera. Yes, the internals are amazing, the guts of the camera are terrific, but when you're awkwardly holding it out, taking pictures with this device, admit it, you're always 22% certain the thing is going to pop out of the delicate cradle of fingers that you've constructed to hold it.

And I eagerly take photos with my iPhone every single day.

It is with equal irony that the app I need the most to post my photos is the one I use the least - Instagram. Now, I love Instagram and there is no denying that the team hit on a pitch perfect combination of the right, minimal feature set during a critical rise of mobile phone operating systems. But the majority of my learning about how to take and edit photographs with my iPhone has occurred outside of Instagram where I figured out how to be a better storyteller.

Here's what I've learned and how I've learned it:

Find your edit. The initial attraction of Instagram is one-stop shopping. The application does represent a complete solution for capturing, editing, and posting a photo. Instagram found a sweet spot for the core set of essential tools, and much of my early photography with it was spent exploring what I could capture in a square photograph and how that capture might interact with Instagram's clever spectrum of filters.

There is a special pride that comes from taking and posting a photograph that you feel needs no editing - when you've found that perfect combination of composition and color. But in my experience, the majority of photographs will benefit from some type of editing. I came to this realization with my beloved Gotham filter in Instagram, which did something absolutely magical with blue skies and clouds. Gotham instantly transformed a bland horizon shot into something that appeared to be from another planet.

For reasons I still don't understand, Instagram removed Gotham from the 2.0 release. Infuriated, I took to the Internet to understand how this filter I loved was constructed. Turns out, it's a non-trivial process outside of Instagram, which originally involved three different applications. The Gotham reconstruction process not only returned an approximation of my favorite filter, it showed me what decent amount of work Instagram did in order to find a set of compelling filters. More importantly, though, I learned that with equal work, I could build any filter I wanted.

You can hang out exclusively in Instagram, but my advice is to figure out how to recreate your favorite filter in other applications, such as Camera+ or Snapseed, because in doing so, you'll discover there are infinite filters at your disposal.

Light is only useful if you can see it. Or its absence. My next discovery has to do with lighting. In flying back and forth between the west and east I discovered I had a cloud problem. I couldn't stop taking pictures of clouds, but I also discovered there were optimal times to capture their shape and texture: sunrise and sunset.

What's going on the during these two distinct times of day? First, there are more yellows, oranges, and reds in the sky as the sun refracts out more of the light spectrum, but more importantly, there are shadows. You're going to read more about my fascination with contrast in a bit, but what is magical about sunrise and sunset is the strange black shapes that slowly stretch across the landscape. Objects you stare at every day are framed by oddly twisted and stretched shadows of themselves and it's these mutated mirror images that capture my eye.

It's instinct for me now. When the sun is either rising or setting, I look where it is in the sky and and I look in two directions: directly at the sun to see what it's playing with:

And then I look around to see what other shadows it's created:

I prefer contrast and drama. My standard editing process starts in Snapseed. I use "Tune Image" to adjust brightness, ambiance, contrast, and saturation. I rarely touch white balance. As you can see, I have a fascination with high contrast and deeply saturated photos. My wife does not and I wonder if that makes her a better casual photographer than I, but then I stop wondering because such mental excursions are a waste of energy.

While feedback from likes or comments are one of my favorite ways to get a sense of how folks feel about a photo, and while I love to see what other folks are building on Instagram, the joy of a great photograph is that it speaks to you. I love finding circles, deep perspective, vibrant colors, and contrast everywhere. This is why my last move in Snapseed is to try the Drama filter. This unique filter performs some crazy HDR transformation that finds unexpected depth in clouds, carves out deep shadows, and adds texture everywhere. Drama often takes my breath away.

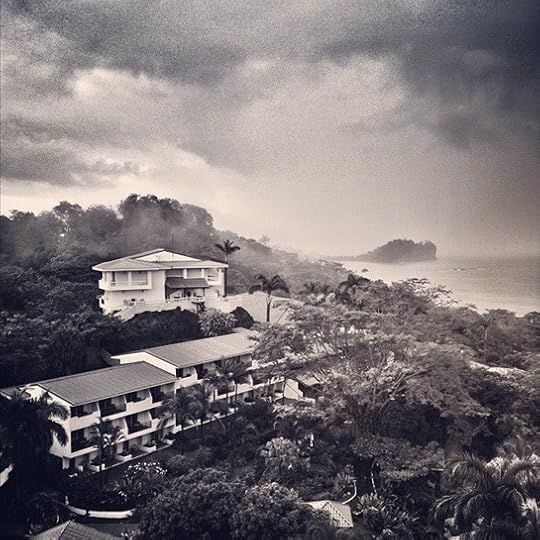

Black and white strips away color and reveals unexpected stories. I'm just back from a family vacation in Costa Rica and if Costa Rica were to nominate a national color that color would be green. In the areas we traveled, the average rainfall ranged from 80 to 200 inches a year and that means green everywhere. Given my preference for deeply saturated colors, you'd expect lots of jungle, and Costa Rica didn't disappoint, but my favorite jungle shot didn't have a smidge of green.

A lesson I learned in my reverse engineering of the Gotham filter was the strange power of black and white filters. The removal of color allows other elements of the photo to emerge. The haziness of the rainy sky. The pleasing geometry of buildings. The perspective afforded by fog. The original image is a blast of greens and reds and would've shown little of what I just described. The lesson of black and white photos is similar to the lesson of Instagram: what you remove, how you reduce, may allow previously hidden simplicity to appear.

My process for black and white varies, but the approximation of Gotham starts in Snapseed, where I perform the same image tuning as I described above. I follow that up with applying the red, black and white filter before I jump over to Camera+. In this app, I do the following:

Select the Darken filter.

Apply the Silver Gelatin filter at 50%. Apply changes.

Apply the Vibrant filter at 25%. Apply changes.

Lastly, apply the Cyanotype filter at ~10%. Apply changes.

Instant gorgeous Gotham. R.I.P.

People lose their shit for fog. Or, maybe, there is nothing negative about negative space. My last learning has to do with disproportionate value. There are a couple of semi-guaranteed moves that generate good photos and I think they relate to this article's theme.

First, if you want a reaction from your audience, I recommend fog. Like... any fog. I can rarely predict the audience reaction to my photos, but I know that fog is a crowd pleaser. I know this because one of my first well-received photographs, I believe, is only magical because of the fog that provided an otherwise unattainable Middle Earth quality.

Second, and similarly, I want to note the power of negative space. My gut instinct is to fill the photographic frame up with stuff, and that's precisely the opposite of what your eye wants to see. If you go back and look at my photo history, you'll notice I have a real problem with horizons and clouds - I can't stop taking pictures of them. However, you might also notice that the amount of horizon I capture is slowly decreasing. Negative space is the space around and between the subject(s) of an image, and what I've discovered after several thousand Instagrams is that the more negative space I place in a photo, the more story it tells.

Find a Story

A good picture tells a complete story. There is a beginning, a middle and an end. Unlike an actual written story, the words are captured in objects, color, light and arrangement. But the combination of each of these aspects is only half the story. The other half is provided by the viewer. It's the story they tell themselves as they process the image in a way that is entirely unique to them.

My belief is that good photography involves the same process as good application and hardware design. You find the essence of what you are photographing, writing, or building and that means you need to be willing to strip away the unnecessary over and over again. In a world where we love to preserve our options, reduction feels limiting, but sensible reduction allows the consumers of the work to better tell their own story.

November 14, 2012

Stables and Volatiles

Stephen was a hired gun at my first start-up. His contract started a year before I arrived, but he was long gone before I walked in the door. The story goes that when Stephen started, he found a small, solid team of five engineers, a QA lead, and a project manager. They were slowly and steadily going... nowhere. After two weeks of watching the team's slug-like pace, Stephen was fed up.

Stephen, a guy we hired as a temporary contractor to tidy up our database layer, grabbed the greenest of engineers, moved into the ping-pong room, and told the engineer, "We are not leaving this room until we can see the application actually work."

The engineer asked, "What does 'work' mean?"

Stephen, "I don't know, we'll figure it out when we get there."

Ten days later, a reeking ping-pong room contained three-quarters of the engineering team, none of whom had slept in the last 48 hours. The green engineer stood up and demoed the application. For the first time in the company's history, the team could see and touch the idea. Three months later, we released 1.0.

It reads like an inspirational story. The whole team mobilizing for one last push to get the product out the door. Except Stephen didn't mobilize the whole team, he marshaled three-quarters of it. While the folks who weren't sleeping in the ping-pong room clapped just as loudly when they saw the product, they knew the corners Stephen had cut to get it done because they'd seen the code. They knew many features were smoke-and-mirrors placeholders, they had big questions about scale, and most of all, they knew it'd be their job to clean up the mess because they'd seen Stephen's ilk before. They knew he was a Volatile.

The Factions

The reward for shipping 1.0 is a deep breath. Whew, we did it. In the days, weeks, and months that follow shipping 1.0, the work is equally important to your success. But you never forget the moment when you consider the product done, because you are intimately aware of the blood, sweat, and tears it took to get it there.

I've written a lot about shipping 1.0, but it's only recently that I've been thinking about what happens after a successful 1.0. First, yes, there is someone coming to eat you, but the act of shipping 1.0 creates an internal threat as well. The birth of 1.0 initiates a split of the development team into two groups: Stables and Volatiles. Before I explain why this rift occurs, let's understand the two groups.

Stables are engineers who:

Happily work with direction and appreciate that there appears to be a plan, as well as the calm predictability of a well-defined schedule.

Play nice with others because they value an efficiently-run team.

Calmly assess risk and carefully work to mitigate failure, however distant or improbable it might be.

Tend to generate a lot of process because they know process creates predictably and measurability.

Are known for their calm reliability.

Volatiles are the engineers who:

Prefer to define strategy rather than follow it.

Have issues with authority and often have legitimate arguments for anarchy.

Can't conceive of failing, and seek a thrill in risk.

See working with others as time-consuming and onerous tasks, prefer to work in small, autonomous groups, and don't give a shit how you feel.

Often don't build particularly beautiful or stable things, but they sure do build a lot.

Are only reliable if it's in their best interest.

Leave a trail of disruption in their wake.

Lastly and most importantly, these guys and gals hate -- hate -- each other. Volatiles believe Stables are fat, lazy, and bureaucratic. They believe Stables have become "The Man." Meanwhile, Stables believe Volatiles hold nothing sacred and are doing whatever they please, company or product be damned. Bad news: everyone is right.

Because of this hate, there's a good chance that these two factions are somehow at war in your company, and while all your leadership instincts are going to tell you to negotiate a peace treaty, you might want to encourage the war. Hold that thought while I explain where the war started.

A Stable Evolution

I'm of the opinion that many successful Stables used to be Volatiles who are recovering from the last war. Think about it like this. Go back to your successful 1.0. You're taking your deep breath because you appear to be past the state of imminent failure, enough money is showing up, and the team is no longer working every single weekend just to keep the lights on. My question: "How'd you get there?"

Someone bled.

The birth of a successful 1.0 is a war with convention and common sense. It is built around a handful of Volatiles who believe that "We can bring this new thing into the world," and no one believes them. It's excruciating, and the majority of Volatiles who embark on this quest will fail, but if and when success arrives, those who survive are scarred and weary. More importantly, they are intimately aware of what it cost to get here and they want to protect it.

This is how a perfectly respectable and disruptive Volatile transforms into a Stable. They are eager to make sure the team does not return to a war-like state because, well, war sucks. These emerging Stables build process and carefully describe how things should be done because they have the scars and experience to do so. They hire more people and they become a moderate-sized, well-run engineering team. They hire people who are familiar, who have traits that remind them of themselves. Yes, they hire engineers who are predisposed to be Volatile.

Unintentionally, they plant the seeds for the next war.

See, these new Volatiles arrive and they look around and they are told, "This is a well-run machine built on the success of the first war. Shiny, isn't it?" The Volatiles nod cautiously, but in their heads they're thinking, "Shiny. Polished. This isn't very exciting. I mean, it's certainly pretty, but where is the threat? Who is coming to eat us?" The irony is that the Volatiles want exactly what created this company in the first place. The thrill of 1.0, but when they make their intentions known, the recently minted Stables show up and start yelling, _YOU THINK YOU WANT 1.0 BUT LOOK AT THESE SCARS - YOU DON'T WANT A PIECE OF THIS. IT'S WAR. WAR SUCKS._

The Volatiles nod and acquiesce, but this does not scratch their disruptive itch. They continue to believe the right thing is something risky and something new. We need to make a big bet.

This transformation of first generation Volatiles to Stables among the arrival of the second generation Volatiles is the source of an amazing amount of organizational discontent. It's how a team that used to cohesively sit on the same floor stratifies and fractures into multiple teams on many floors where there is an emerging, unfamiliar sense of us and them. It's the beginning of the worst kind of politics and gossip, and it's often the source of the vile reputation managers receive for being out of touch.

The arrival and organization of the new Volatiles actively disrupts the organization. While it is dangerous work and well-intentioned people will yell at me, your job as a leader is to nurture this disruption.

Wait, What?

Once you're successfully past 1.0, you have a choice: coast and die, or disrupt. No one in history has ever actually chosen coast and die; everyone thinks they're choosing the path of continued disruption, but it's a very different choice when it's made by a Stable than by a Volatile. A Stable's choice of disruption is within the context of the last war. They can certainly innovate, but they will attempt to do so within the box they bled to build. A second-generation Volatile will grin mischievously and remind you, "There is no box."

Many incredibly successfully multi-billion-dollar companies fall under my definition of coast and die. They are sitting there, impressively monetizing their original excellent 1.0 for years -- for decades -- but there's a smell about them. Sure, the money is still pouring in, but what have they built that is actually new? They have huge sales forces, impressive glossy ad campaigns, and legions of lawyers, but you can't point at anything that they've built in the last five years where you thought, "Holy shit." That distinct musty smell is the lack of Holy Shit, and its presence sends Volatiles running, because that's the smell of stagnation. Volatiles want nothing to do with a group of people who no longer take risks because they believe the stagnation is death.

As a leader, you need to figure out how to invest in disruption, and this is counter-intuitive because disruption, by definition, is destructive. It breaks things that others covet.

While Apple is a good example of a company that doesn't give a shit about wars of the past, I think Amazon is an equally solid example of a company that has chosen to invest in their Volatiles. In 2002, they introduced Amazon Web Services and we all collectively scratched our heads: A company that sells books online is getting into online services for web sites? Whatever.

Present day, and I just returned from Ireland's amazing FunConf where I stood in a room full of developers who are intensely dependent on Amazon's vast array of web services. My belief is that years ago, some Volatile thought, We are not a seller of books, we are builders of technology. It's this type of Volatile thinking that has Amazon going toe to toe with Apple in an entirely different space. Who thinks it'd be crazy if Amazon did a phone? Not me.

I don't know the inner workings of Amazon, but when I see strategies that diverge wildly from conventional wisdom, I smell Volatiles at work.

Take Crazy Risks

I believe a healthy company that wants to continue to grow and invent needs to equally invest in both their Stables and their Volatiles.

Your Stables are there to remind you about reality and to define process whereby large groups of people can be coordinated to actually get work done. Your Stables bring predictability, repeatability, credibility to your execution, and you need to build a world where they can thrive.

Your Volatiles are there to remind you that nothing lasts, and that the world is full of Volatiles who consider it their mission in life to replace the inefficient, boring, and uninspired. You can't actually build them a world because they'll think you're up to something Stable, so you need to create a corner of the building where they can disrupt.

These factions will war because of their vastly different perspectives. Stables will feel like they're endlessly babysitting and cleaning up Volatiles' messes, while Volatiles will feel like the Stables' lack of creativity and risk acceptance is holding back the company and innovation as a whole. Their perspectives, while divergent, are essential to a healthy business. Your exhausting and hopefully never-ending job as a leader of engineers is the constant negotiation of a temporary peace treaty between the factions.

We were cleaning up the results of Stephen's Volatile engineering coup for years, but during that clean-up we went from zero customers to 30. We went from a handful of volatile engineers to a stable company of 200, and this was partly because Stephen gave us a chance to see our platform. But our platform was never done. The boost from Stephen got us out the door, but we were forever in a state of functional incompleteness and architectural inconsistency. The second-generation Volatiles pointed this out, but the Stables assured us that better is the enemy of done.

Eventually, the second platform began. It started as a side project in a silent fit of Volatile rage. It developed over weeks into the beginnings of an actual strategy, but the rebellion started too late. One big enterprise customer dropped us loudly when it was clear we never built for the scale we were selling. Credibility crumbled, the Volatiles bolted, and we sat there in the middle of the dot-com implosion consoling ourselves that "there were macroeconomic forces outside of our control", which is exactly what a Stable says when they've surrendered.

November 11, 2012

Innovation is a Fight

Apple is eventually doomed. Yes, the most valuable company on the planet will slowly fade into stagnant mediocrity. It will be replaced by something that they will not predict and they will not see coming. This horrifically efficient culling is a fact of life in technology because it is an industry populated by a demographic intent not on building a better mousetrap, but who avidly ask, "Why the hell do we need mousetraps?"

Apple's doom will start quietly and I doubt anyone can predict how it will actually begin. It will be historians who, decades from now, will easily pin its demise to a single event that will appear obvious given years of quantifiable insight. And it will only be "obvious" because the real details will have been twisted, clouded, or forgotten entirely, so it will all seem clearer, faster, and simpler. Their explanation will start with the passing of Steve Jobs, and they will draw a clear line to a subsequent event of significance and will say, "Here. This is it. This is when it began."

Executive rearrangements have been going on at Apple for years. Remember Mark Papermaster? Avie Tevanian? Jon Rubinstein? Steve Sakoman? Tony Fadell? Sina Tamaddon? Bertrand Serlet? Fred Anderson? Nancy Heinen? There's likely a compelling departure backstory for all of these key players, but the sheer length of this incomplete list gives some perspective to the recent announcement regarding Scott Forstall and John Browett - no big deal. Happens all the time.

Maybe.

Like Papermaster before him, all the signals point to the fact that Browett was not a cultural fit, which is Apple-speak for the organism having an intense allergic reaction to his arrival. Forstall, however, was old school. In my years at Apple, the Caffe Macs chatter about Forstall was that he was the only legit successor to Jobs because he displayed a variety of Jobsian characteristics. Namely:

He was an asshole, but...

Success seemed to surround him, and...

No one was quite sure about the secret recipe to achieve this success.

While I'd continued to hear about the disdain amongst the executive ranks about Forstall after I left Apple, I was still shocked about his departure, because while he was in no way Steve Jobs, he was the best approximation of Steve Jobs that Apple had left. You came to expect a certain amount of disruption around him because that's how business was done at Apple - it was well-managed internal warfare. Innovation is not born out out of a committee; innovation is a fight. It's messy, people die, but when the battle is over, something unimaginably significant has been achieved.

With Forstall's departure, I believe his former lieutenants have been distributed to Bob Mansfield, Jony Ive, Eddy Cue, and Craig Federighi. While there is no doubt in my mind that these are talented and qualified leaders, are they disruptive? Are they incentivized as such? Because from where I'm standing, the guy in charge is possibly the most talented operational leader on the planet. And an operational leader's job is ferret out and exterminate all things that make their world less predictable and measured.

The word that worried me the most in the press release was in the first sentence. The word was "collaboration". Close your eyes and imagine a meeting with Steve Jobs. Imagine how it proceeds and how decisions are made. Does the word collaboration ever enter your mind? Not mine. I'm just sitting there on pins and needles waiting for the guy to explode and rip us to shreds because we phoned it in on a seemingly unimportant icon.

As someone who spends much of his time figuring out how to get teams to work together, the premium I'm placing on volatility might seem odd. I believe Apple benefits greatly from having a large, stable operational team that consistently and steadily gets shit done, but I also believe that in order to maintain its edge Apple needs a group of disruptors.

Love him or hate him, Scott Forstall's departure makes Apple a more stable company, and I wonder if that is how it begins.

October 14, 2012

The Elegant Email

For me, the amount of email that arrives is inversely proportionate to my amount of free time. This means the less time I have to read mail, the more mail that arrives. Greater minds than mine have attempted to tackle this unfortunate time management situation, so I'm going to keep it simple. You and I are busy people. We may or may not know each other, but we have the same goal - how can each of us effectively surf an ever-growing pile of information?

To this end, I would like to come to an agreement with you. Let's agree to small set of rules that we'll follow when we mail each other, ok?

An Email Contract

Before we start, there are two kinds of email: original content and follow-on content. Original content, an email that is the first mail in a potential thread, is the focus of this piece unless otherwise noted. Follow-on mails, the ones where everyone else jumps into the conversation willy-nilly, are an entirely other article.

Let's begin...

Say something of substance with your subject. (Perhaps with poetry.) The first line of defense against the absurd number of unread messages is the subject line. For a new topic, my expectation is that the subject line gives me an inkling of what I'm about to read. "Question" is not a subject. "Question regarding the impending disaster in engineering" is a better subject. The best, "Calamity is a man's true touchstone."

As I'm considering a subject line, I work under the erroneous, paranoid assumption that the someone I'm sending an email to is not going to read it. Chances are that they will, but when I fret about them not reading the mail, I get amazingly creative about making the subject line descriptive, relevant, and poetic.

Yes, poetry.

In the world of databases, there is a concept called an index. Simply put, an index makes finding the location of a single row of data much faster. A substantial portion of the field of computer science is devoted to the design and analysis of these data structures because computer scientists know what you know: finding what you're looking for quickly is awesome.

When you take a moment to add a bit of art to your subject line, you are indexing the mail in the minds of those who read it. You are making an impression, and that means not only are they more likely to read it, but also to remember it.

A three (or four) paragraph limit. I do not believe email is not a long form communication medium, and my rule of thumb is that an email should be no longer than three (or four) paragraphs. You might hate this stipulation.

Here's the deal. I'm not suggesting the three-paragraph limit because I'm in a hurry. What I'm asking you to do is think. I've made it past your subject line - super. Now, I'm staring at 14 paragraphs regarding whether we should or should not open a new office in Berlin. My unfortunate knee-jerk reaction to 14 paragraphs is to flag the message for later reading. Flagging a message for later reading creates the same fake sense of accomplishment as putting an item on a to-do list - you give yourself permission to never think about it again.

Our Berlin office is a big decision and every single one of your 14 paragraphs demonstrates this importance, but are we really going to make a decision of this magnitude via email? No. There's great content in your Berlin office opus, but I'm going to have lots of questions for which you are going to ask for clarification, and suddenly we're in the middle of a lengthy email thread and my question is, Wouldn't this have been easier if we had just sat down and had it out face to face?

One of the many joys of email revolves around instant gratification. There is a topic that is suddenly bugging you in the middle of the night, and you're not going to sleep until action, any action, has been taken, so you write an email. I get it.

Think. Yes, you want the problem solved, but is email the right medium for solving the problem? If the answer is yes, then start writing. When you get to that fourth paragraph, ask yourself again: is email the right medium? Are you writing this because you want to get it out of your system RIGHT NOW or because email is the correct place to start this conversation?

As a person who spends a good portion of his life figuring out what he thinks by writing it down, I have learned to recognize when an email is therapy is for me and only me. I still write that 17-paragraph opus about the horrifying mess that is our interview process, but halfway through the rant I realize this mail is just for me.

The amount of editing time doubles for each paragraph. Your instinct is to hit "Send". It's so satisfying to get to the end of your thought and just fire it off into the ether, but my request is that you reread it. I am particularly bad at this.

What makes an idea interesting to me is partially that I'm thinking it. In fact, it's so interesting that I'm going to write you an email on this interesting topic because by doing so I'm infecting you with its exciting and obvious interestingness. For me, the problem is that in my rabid fury of interestingness, my typing suffers. I drop words, I don't tie up logic, and often what starts as a well-intentioned email turns into a confusing, multi-paragraph mess.

With each paragraph you write, double the amount of time you spend editing. It's not just grammar and spelling errors that might be hurting your credibility. Is your point clear, literate, and concise? Have you pruned aggressively to find the core of what you're saying? With each additional paragraph, the higher the chance becomes that you've made an egregious mistake that might make your email confusing and forgettable.

If your instinct is hit to sent "Send" without any editing, my thought is that you're more interested in therapy than progress. This thing you are writing is important or we wouldn't be here, but by choosing to send this thing to others, the burden of clarity and coherence is on you.

A Sense of Doneness and Humanity

It takes practice, but after I've written three (or four) paragraphs, after I've reread them three (or four) times, after I've written my alliterative subject line, I am looking for a calming sense of doneness. This email... is done. It clearly, intelligently, and briefly describes my thought. I've exposed a truth. I've constructed a call to action. Now I finish with a smidge of humanity - I sign it.

I look at every signature in every single email and I assign a humanity value to it. Sincerely? Cordially? Best? Thoughts? No signature at all? You've taken the time to write these paragraphs, to transcribe your thoughts, and you've left me hanging?

At the gig, we're writing a lot of mail because we're very busy. I've noticed that we've taken to blasting through our paragraphs and either using a default signature or no signature at all and I'm of the opinion that an unsigned email is a lost opportunity to say something small and important.

Email is imprecise. It is easy to misinterpret. Email is a digital force of nature. It's not going anywhere, but email, while convenient and sometimes efficient, is dehumanizing. An original signature tailored to the email, no matter how brief, is a small reminder there is a human behind these three (or four) paragraphs who is worth your attention.

With hope,

Rands

September 17, 2012

The Second Test

A quick search of Rands in Repose archives reveals that I have never mentioned Piers Anthony as a major influence. I consumed the Xanth series over the course of several years, and am certain much of a formative teenage wit is based on the literary stylings of Anthony.

These books have not aged well, or perhaps I've aged too much. When I recently picked up The Source of Magic, I appreciated the trip down memory lane, but it's a lane firmly entrenched in my youth. Other books of the time, Ender's Game and Asimov's Robot and Foundations series, have stood the test of time as evidenced by my ability to endlessly reread them.

Anthony wrote a mostly forgettable series called The Bio of a Space Tyrant. The series describes the rise of the Tyrant of Jupiter, hilariously named "Hope Hubris". Don't read it, but know that that main character's talents has stuck with me through the years because it relates to why you think engineers don't like you.

Show Me Your Power

Whether you're an engineer or not, if you're reading this there is a good chance that there are engineers in your life. And that means there is an equal chance that at some point an engineer appeared to not like you and you weren't quite sure why. Engineers are not a rare breed these days, but they are an odd breed. I've documented a lot of their, uh, attributes over the years. I've explained why they're system thinkers, where they like to work, and why they hate meetings, but I haven't explained why they hate you.

Ok, hate is a strong word. How about distrust? How about the sense that when you're sitting in the room that they're looking at you like you're an alien when all you're thinking is you're the alien.

There is a variety of nerd quirks that can lead to this social impedance. Yes, we are generally low on emotional intelligence. Yes, our preference is that we could resolve whatever called for this crap meeting via email. Yes, we don't like like talking to, you know, people, but a lot of that social awkwardness goes away when you've passed the Second Test.

Back to Piers Anthony's forgettable Tyrant series. Hope Hubris (seriously, that was his name) had the ability to look at someone and immediate understand their character. As the series progressed, characters in the book would ask him to "show me your power" and he'd immediately respond with a complete analysis of their character. I'd dig up a specific example, but I can't bear to read these books again.

Piers Anthony is a perfect read for the nerd teenager. He taps into the unabashed imagination of youth combined with the complex insecurities of the teen years. He also empowers. His Xanth books describe a land where magic exists everywhere and each person has a unique magical talent. In Tyrant, Hope's character assessment talent is the same type of empowering, impossible magical talent that appeals to the awkward nerd teen.

I've never forgotten Hope's talent because it's a test I employ on every new person in my professional world. It is the Second Test.

The Second Test

In your company, there are three kinds of people. There are those you are aware of, but who don't immediately affect your world. There are those who mildly affect your world and upon whom you have a lightweight dependency. And there are those who are an active part of your world. You depend on them.

I don't want to depend on you. It's nothing personal, it's just that as an engineer I irrationally believe that anything I don't build with my own hands is going to get fucked up by someone else. I believe this because I've spent a good portion of my life watching other well-meaning people sit down at a computer and simply... make things harder for themselves.

It's an irrational, unfair, and annoying perspective, but when you're sitting there across from an engineer who has been forced to depend on you, he or she is wondering, "How are they are going fuck up my shit?"

The good news is that you already passed the First Test - you were hired. The folks sitting around the table hired you and that means they believe you should be there. Hopefully, it was a nontrivial process to get hired. Hopefully, they put you through a professional wringer and now that you're hired you're basking in a sense of accomplishment. Bad news, the Second Test is harder.

The Second Test is: you must build something of value as perceived by the organism.

It's a deceptively slippery test, so let me explain each part:

You must build something. You're thinking that I'm talking about coding or designing, but I'm not. I'm talking about a thing that you built by yourself, or for which you led development with others. You have mad skills of some sort and you have used those skills to build something that has previously not existed for the team.

Of value. This thing that you've built, this process that you've defined, this story that you told, it must be clear what value it's adding to the company. You rebuilt the front page of the website - terrific - does it tell the story of the company better? Does it feel like the company? You optimized our bug tracking system - splendid - did you actually make it better or are you just trying to show you can do useful stuff? This leads us to our final clause.

As perceived by the organism. This is the hard part. I see that you've built this thing and I attended the meeting where you eloquently explained the value of this thing, but the test isn't passed without independent confirmation. Even if I sat there nodding the entire time as you pitched me on the value, I'm not signed off until Arthur walks by, sticks his head in my office, and says, "Did you see the thing? That is going to save me hours each week. Awesome."

Engineers are meritocratic, which means we don't really care about your resume or your title. While your resume might be an interesting story that eventually led to your hiring, we want to see what you can build. Right now, that alien sitting across the table is wondering about your power. You passed the First Test, so the question now is, what power do you have and how are you going to use it for good? What you see in their eyes is not hate, it's a deep skepticism.

I'm Skeptical of Experts

An unwatched successful business gets fat. The money pouring in means there's far too much work, which means you go on a hiring spree. What was 15 folks rapidly becomes 50, and the experts start to show up. Experts are the folks who are allegedly really qualified to do a job. See, at 15 people everyone did a little bit of everything, but there is no time for that now because of the success. You think you need HR, Marketing, Sales, and Business Development.

Incorrect. What you need is people who get shit done.

I am not suggesting that the hardworking people in these other disciplines don't have amazingly complex and difficult jobs, but I do think they should be able to clearly describe the work they do and the value they provide... to anyone. They need to pass the Second Test, and that means being able to fully and clearly explain your job to the rest of your team not with words, but with action.

Most folks believe that if they can describe a job that they can do it. Most folks are wrong. I've been spun and burned by too many fast-talking, charismatic experts in my career to trust anything but results. The Second Test is not the exclusive domain of engineers. In most groups of people, there is a means by which you earn your stripes. The difference with engineers is a combination of their low tolerance for spin and their deep desire for measurability.

Passing the Second Test when engineers are involved means that you've built something that fully and clearly explains your power.

August 27, 2012

You're Not Listening

I don't want to write this article. I believe there is no way to provide advice about listening without sounding like a touchy-feely douchebag. But I'm going to write this article because there is a good chance that your definition of listening is incomplete, and what I consider to be obvious and simple ways to listen are not obvious at all.

The problem starts with the word: listen. Of course you know how to listen. You sit there and let the words into your head. Perhaps your definition is more refined. Maybe your definition of listening involves hearing because you're aware of that switch in your head that you must flip to really hear what a person is saying. It's work, right? Pulling in all the words, sorting them in your head, and mapping them against the person who is speaking. That is listening, that is hearing, but if that's all you're doing and you're a leader of people, then you're still only halfway there.

Let's start with the most basic rule of listening: If they don't trust you, they aren't going to say shit.

A Listening Structure

First, context. The type of listening I'm going to describe is not the listening you're going to use all the time. This is the aggressive listening I employ with co-workers and friends, but once you understand the different parts of this seemingly laborious listening protocol, you'll start using them elsewhere. Another thing: there's armchair psychology going on below. I'm going to say "I feel" a lot and your inner systems nerd may rage, but my experience, after years of listening to all types of people, is that these are useful moves.

Second, it would be easy to flip this article and make it a piece about healthy and useful conversations. Some of my advice has to do with building these conversations, but my belief is that a good conversation starts with the ability to listen. A good conversation is a bunch of words elegantly connected with listening.

Let's start...

Open with innocuous preamble. In most discussions or 1:1s, you have an agenda. There is a question that you really want to ask. Don't start with this question. In fact, start with something small and innocuous. Crap openers like, "How are you?" or "What's up?" are actually better than blindsiding someone with, "Hey, I hear Oliver lost his shit in the design review. Weren't you running that? What happened there?"

Your preamble defines a quiet, safe place where you and your whomever can transition from wherever you were before you sat down together to this new, calm place where intelligent and reasonable conversation occurs. Your preamble states your intent: "Outside of this door it is professionally noisy. Inside of this room, we are going to talk and listen."

Look them straight in the eye and don't look at the clock. Once you're past your opener, it becomes a real challenge. See, Oliver losing his shit is actually a really big deal with lots of implications, and that's one of three disasters in progress today. Your preamble set the stage, but with all the disasters in progress, you need to focus.

It's simple, it's trivial, but attention is defined by eye contact. Think about the last time you sat in the audience in a huge presentation. Remember when the presenter walked to your side of the room and looked you straight in the eye? WHAM She's... looking at me. What I am going to do? For reasons I do not understand but completely feel, we are more mentally engaged when we're staring at each other's eyes. Eye contact is the easiest way to demonstrate your full attention and it's also the easiest way to destroy it.

23 minutes into your 1:1, you remember an essential part of one of the other disasters going on today and you glance at the clock... and they notice. Listening is built on a evolving attention contract that initially reads: "He is really busy and has no time for me". Each time that you successfully sit down and give someone else your full attention, the attention contract gradually evolves. After a time, it reads: "He and I meet each week and we honestly talk about what matters".

A single glance at your clock is not going to void the attention contract, but early on in a relationship it can certainly set the tone.

Be a curious fool. This is a restatement of advice I gave in the 1:1 article: "Assume they have something to teach you". As a lead, manager, or director, early on in establishing the attention contract, they're going to be nervous. They're going to assume that you'll be talking and not listening and the exact opposite is what you're looking to negotiate.

It's a game. Keep asking stupid questions based on whatever topics arrive until you find an answer where they light up. She sat straight up when we started talking automation. The first time he didn't seem nervous was when he talked about traveling. Being a curious fool means talking about things that appear to have no substantive value to the conversation or the business - that's ok. Over time, your foolishness will allow you to build connective tissue, to further develop your mental profile of this person. When you understand what they really care about, you'll be better equipped to have bigger conversations, and that is where trust is built.

Validate ambiguity, map their words to yours, and build gentle segues. There will be bumps while you listen. There will be strange sentences and awkward pauses, statements that make no sense, and unanswerable questions. And your job during all of this confusion is to maintain the conversational flow.

In my head, a good conversation has a steady, healthy tempo. This. Is How. We Speak. Listen. And Learn. When a bump in the conversation arrives, I ask myself: do I need to understand what just happened or is it in our interest to move along? If further understanding is the move, I repeat their last sentence, "What I hear you saying is..." and then I repeat my version of their thought.

It feels redundant, repeating what was just said. It feels inefficient because the words were just out there, but trust me when I say that a decent amount of your professional misery is based on the simple act of one person misinterpreting the intent of another and misinterpretation avoidance isn't even the goal of this move. The goal is make it clear to the other person: "I know you just said something complicated and I am directing my full attention at understanding what you said and what it means".

There are two possible reactions to this restatement: the nod or the stare. The nod means, "You heard me correctly and let's move along". The stare means, "I don't know what you just said". I counter the stare with another restatement, except this time I use more of the words and language that were in the original idea - I make it sound like they said it, but it's me talking.

The last tempo maintenance move I have is the segue. Similar to your preamble, part of your job is to discover how to move from one topic to the next. The validation and repetition moves I suggest above one one way to pull this off, but a segue can be even simpler. It can be, "Ok, next thought?" or "And then what happened?" A conversation without clarification and segues is an exhausting circular exercise where two people are working increasingly hard at not understanding what the other is saying and failing to get to the point.

Pause. Like, shut up. There will be times when you're listening and it's clear they want to say something else. They're dying to say it, but you cannot find the question, the segue, or the words to pull it out of them. In what is one of the more advanced listening moves, my advice is: shut up.

Yes, I just told you to gently guide a conversation by listening and finding segues from one thought to the next, but that's not working. It's time to be quiet for as long as it takes. When I'm pulling this move, I sit there maintaining eye contacting and repeating to myself: I will not be the next person to speak. I will not be the next person to speak. It's maddening... for both you, but that's the point. The conversation is not headed where it needs to go, so you're going to disrupt with silence.

You are not in their head. No matter how empathic or smart you believe yourself to be, the story they're telling themselves is vastly different than the story you're telling yourself. In these awkward silences, I find people volunteer the part of the story they really want to tell.

If They Don't Trust You, They Aren't Going to Say Shit

Everything I just described can be faked. Anyone who has been pressured into buying something they did not need has been on the receiving end of faked listening skills, but there's a reason why, when you leave the car dealership, that you feel used. You slowly become aware that you were manipulated with a false sense of familiarity and connection. You realize that while they showed interest in you, they didn't really listen. They have no clue who you are. It was an empty conversation facilitated by manipulation cloaked as listening skills.

Listening is work, and the difference between listening well and making them feel like you're selling them a car has to do with intent. Each time sit down to listen, my goal is the same: continue to build trust with the people I depend upon and who, in turn, depend upon me. It takes months of listening, but I want a professional relationship where my team willingly tells me the smallest concern or their craziest idea. Think of healthy listening as preventative relationship maintenance.

The longer you're a bad listener, the smaller your world gets and the narrower your mind becomes, because you're not exposing yourself to different ideas and perspective. The better you become at listening, the more of the world you'll see, and the world knows a lot more than you.

August 12, 2012

One Job

Look up for this article and say the time out loud.

Rands, it's 10:35 am.

Now, I can tell when people are reading the site. I'm a nerd which means I've got all sorts of analytics on this site so I know when you're collectively reading, what you like, and where else you might stumble on the site, but for you... it's 10:35am and the fact you're reading at 10:35 am means you're not really that busy.

I want to be busy. Not "I've got a bunch of stuff to do" busy, but "The weight of the important work I need to do is literally crushing me" busy. This state is not for everyone and while I'm extremely appreciative of the fact you're reading this site, if you're at work and you're reading the site at 10:30 am then there is a chance you're not busy.

There are many forms to not being busy. You might just be getting your day started with a cup of coffee, you might be on your lunch hour, or you might have seven precious minutes to take a deep breath amongst your crushing responsibilities, but here's my question: is the lack of busy more fun than your job?

I've debated many different sponsorship strategies for the site and recently stumbled on one that will both support the site while helping your busy situation. Rather than promoting a product, I'm interested in getting you a new job because there is a finite chance that reading this site might be more fun than your current job.

Starting next week, I'm kicking off a weekly sponsorship program where savvy employers interested in interacting with the equally savvy Rands audience can purchase a spot on the front page of the site for one job. Not every job, just one. If you're a prospective employer, you can find more details regarding the program here.

You're in a hurry. Someone is coming to eat you. You are underestimating the future. Most important, you're the business. My belief is you should pour your heart into your job. I'm very interested in making sure that you're making the most of your time you have and my hope is the presence of frequent and high quality jobs on Rands in Repose might not just improve your busy, but your life.

July 22, 2012

One More Thing

As each post-Steve Jobs event comes and goes, I wonder whether they'll ever use "One More Thing" again. For those who haven't watched a Steve Jobs keynote, "One More Thing" is an anticipatory moment that the Apple faithful have come to expect at the end. Just when it appeared that Steve was done with his presentation, he'd stop, look confused for a moment, raise one finger, and say, "Wait, you know, we have one more thing."

As you can see from that collection of "One More Thing" introductions, early in his return to Apple, Steve literally acts like he almost forgot to introduce a product that has likely been in the works for years, involving hundreds, if not thousands, of people. Understanding the reasoning for this well-orchestrated and completely manufactured moment gives you a glimpse into the identity of Apple.

It's Not Secrecy

Every week for several years, I'd have lunch with Shane at the mothership. He and I went to college together and landed at different parts of Apple. I was in Mac OS X and he was... somewhere else. Every couple of lunches, I'd throw it out there, "So, what are you working on?" and I'd receive precisely the same response, "You know... stuff."

Two years. Shane didn't give me a single clue what he was working on. I finally figured out that that he was on the Numbers team, Apple's spreadsheet, and I learned about it the same time as everyone else - at a keynote.

Secrecy at Apple is part of its DNA. Information is compartmentalized on a need to know basis, and jumping from one compartment to the next is a pain in the ass. Legitimate needs to understand the impact or direction of a product or technology are heavily scrutinized. Much of your life interacting with folks outside of your group involves a strange abstract language and bizarre body language protocol where you attempt to determine whether the person sitting across from you knows what you know:

Me: "So... do you know about... the thing?"

Them: "The big thing or the little thing?"

Me: "THE thing."

Them: "THE thing for WWDC or the after thing thing?"

Me: "The AFTER thing thing."

Them: "I don't know anything about that."

Me: "Me either."

It's frustrating and at times demoralizing, and it meant that there was a good chance, even as an Apple employee, that when a keynote rolled around you were going to be just as surprised by a majority of the announcements as the rest of the audience. But when Steve walked on stage, you forgot about the secrecy and you began to anticipate. The show started and you realized there was a good chance that your world was going to change in the next 90 minutes.

You realized: it's not secrecy, it's theatre.

Many companies are capable of this type of show, but what makes Apple different is the one-two punch of combining the surprise announcement with the equally surprising announcement - the product is done. In my opinion, these carefully scripted sequence of events amplify both the sense of exclusivity and urgency.

One More Thing

Imagine this: you're sitting in your living room with some friends and for some bizarre reason you've never seen The Empire Strikes Back, so you're fixing this nerd travesty by watching it. You press play, the movie starts, and one of your friends leans over and whispers in your ear, "Darth Vader is Luke's father."

What. The fuck.

When Steve walked on stage, he wanted to tell you a great story. The arc is now familiar: state of the business, preamble to the announcement of the product, actual product announcement, wrap-up of that announcement, repeat as necessary, wrap up the whole damned thing, and... then... sometimes... One More Thing. Hey, yeah, so, by the way, the MacBook Air no longer sucks. Or iTunes no longer has DRM. Or, you don't know it yet, but the iPod Touch is a much bigger thing than you think.

The best stories, the ones we love, have a surprise ending. Since Steve returned to Apple, an essential part of the keynote was the anticipation of the unexpected, and that means aggressive and invasive secrecy. Not because they don't want you to know, but because they want to tell you a great story.

It takes a showman to tell a great story. No one really believed Steve forgot to announce The Thing, but he made an amazing show of it.

Michael Lopp's Blog

- Michael Lopp's profile

- 144 followers