Michael Lopp's Blog, page 53

July 4, 2012

Managing Humans, 2nd Edition

I'm pleased to announce the 2nd edition of Managing Humans is now available.

I'm pleased to announce the 2nd edition of Managing Humans is now available.

I've always wanted to write the preface to the 2nd Edition of a book. To me, a new preface implies that something has both timeliness to it, but continues to have more to say. It's 2012, five years after the initial publication of the first book and the world of technology and leadership continues to evolve and my hope is the second edition of Managing Humans provides further relevant and timely clarification.

Topics of note to this edition:

I've added 14 new chapters. Yes, like previous books, much of this work has already been seen on the blog, but I believe there is a substantive difference to reading these chapters as a collection rather than individually. Some of my favorite articles such as Bored People Quit, Hacking is Important, and The Update, The Vent, and the Disaster are now a part of this book.

Many of the existing chapters have had another editing pass for both errors and clarity. The closing glossary had major editing surgery and remains one of my favorite sources of tweet-sized snark. In related news, I am told that no one knows what a Rolodex is which I find disturbing.

Lastly, several embarrassing chapters are simply gone - I will sleep better at night knowing these poorly shaped thoughts are no longer part of the book.

In the last five years, I've changed my stance on remote workers (We have to make it work), I still firmly believe that you need to spend 30 minutes at least with each of your co-workers (It's the cheapest early warning system you can build), and I increasingly believe the reason you see hackers as CEOs of significant businesses is because the more the hacker mindset infects a company, the healthier the company (And healthy companies survive).

Once more, I'd like to thank the Rands in Repose readers for their continued support. I believe the topics we chew on on this oddly shaped corner of the Internet are increasingly important.

Thank you.

June 27, 2012

Someone is Coming to Eat You

One of my favorite Apple product announcements happened on September 7, 2005. In an Apple music event announcement, Steve Jobs got on stage, gave the usual state of the business update, and then he did something I'd never seen before. He killed a wildly successful product.

The iPod Mini was one of the most popular consumer electronic devices of the time. iPod market share was skyrocketing and the Mini was leading the charge of segmenting the market with a variety of consumer-friendly price points. The Mini, with its size, sleek metal enclosure and variety of colors was loved, and Apple killed it. They completely redesigned around flash memory and shit-canned the Mini's name and design.

The Mini had a worthy replacement - the flash-based iPod Nano - and it was likely that favorable price points for flash memory were a driving force in the new product. But why not milk it? The Mini had been on the market a year and a half and Apple was still having difficulty keeping the Mini in stock. Why kill a best-selling product? I think the reason, and, more importantly, an emerging Apple strategy, was announced as part of the keynote. Steve spent multiple slides showing off the Mini's competition, and, not surprisingly, it looked a lot like the Mini. So rather than letting them catch up, he changed the game.

If there was ever a moment where Steve Jobs tipped his hand regarding what drives him, it was this moment.

Faster Than You

You have a hit. Congratulations, you've built something that is perceived as being best of class. Seminal moment - go you. What's your next move?

Well, we've been busting our collective asses for a good long time and I think it's high time that we all take a break and catch our collective breath.

If your goal is this solo win, if you have achieved everything that you want to achieve with this hit, here's to you - the first round is on me. If you goal is growth, if you want to turn this win into more success, taking the time to catch your breath is the wrong strategy. Like, really wrong.

Your success is a battle plan for your competition. Your success is a public acknowledgement of a strategy that works, and while I appreciate that you and your team are tired, I'm going to be a buzz kill. Your success is your worst enemy. Your success, while hard earned, is a curse.

Your success is delicious. Others look at your success and think, "Well, duh, it's so obvious what they did there - anyone can do that" and, frustratingly so, they're right. Your success has given others a blueprint for what success looks like, and while, yes, the devil's in the details, you have performed a lot of initial legwork for your competition in the process of becoming successful.

More bad news via metaphors. Your enticing success has your competition chasing you, and that means that, by definition, that they need to run harder and faster than you so they can catch up. Yes, many potential competitors are going to bungle the execution and vanish before they pose a legitimate threat but there's a chance someone will catch up, and when they do, what's their velocity? Faster than yours.

Shit.

The reward for winning is the perception that you've won. In your celebration of your awesomeness, you are no longer focused on the finish line, you now lack a clear next goal, and while you sit there comfortably monetizing eyeballs, you're becoming strategically dull. You've forgotten that someone is coming to eat you and if you want until you can see them coming, you're too late. Just ask Nokia or RIM.

The Devil in the Details

Apple's current biggest competitor is itself, and I think Steve Jobs learned this the hard way - from the sidelines. When he returned, one of his first hires was a gentlemen named Tim Cook, and while Tim Cook holds a degree in industrial engineering, he is not an engineer, a designer, or a poet. Tim Cook is an execution machine and he exists at Apple to enable them to pull off one thing - the iPod Mini moment.

By initially focusing on getting Apple out of manufacturing and streamlining the supply chain, yes, he dramatically cut margins and it's a lot easer to kill a bestseller under the warm blanket of an attractive balance sheet. But Cook's larger contribution is an operations team that enables Apple to build and ship new products with increasingly ferocious regularity.

The reason you'll see new iPhone hardware in the fall and yet another iPad come spring is because Steve Jobs knew that he didn't just need to out-design his competition, he needed to out-execute them. Apple is an ambidextrous organization that is equally adept at designing products as they are at making sure millions of them are ready the moment you want them.

If you think nothing revolutionary was announced at the recent WWDC event, if you think you've heard it all, I ask you to think about what they're not talking about. I was thinking about the iPod Mini as I watched the announcement of the MacBook Pro. While it is certainly one of the sexiest pieces of metal on the planet, it also represents painfully consistent execution by Apple.

Yes, you've heard it all before - Retina display, thinner, faster, and more, but I trust Apple when they say they re-imagined everything in the design. I fully expect there is design work in the MacBook Pro that you've never heard of that will give the next iPhone or iPad a competitive edge and I believe the experience they've gained executing this design will allow them to not only maintain, but increase momentum.

How long can they keep it up? I don't know, but I do know that Apple believes the future is invented by the people who don't give a shit about the past.

May 16, 2012

Please Learn to Write

There's been lots of buzz on the topic of whether or not you should learn to code. As an engineer, I don't have unbiased thoughts on the matter. I tweeted Jeff Atwood's piece because, well, I agree that it's pretty silly to think that the world is going to be a better place if the Mayor of New York City learns how to code. I agree with Atwood that his valuable time would be better spent elsewhere.

I believe there are essential skills you learn as an engineer who codes. It teaches you how to structure your thinking, and the process looks something like this:

I have this thing I want to to build.

I have a finite set of tools that enforce a certain set of rules I must follow.

And... go.

Coding is unforgiving. Its structure is well-defined and enforced by whatever interpreter or compiler you might be using. You are punished swiftly for obvious errors. You are punished more subtly for the less obvious ones.

Once you've mastered a particular language, you've also mastered a means of thinking. You understand how to decompose a problem into knowable units, and you learn how to intertwine those units into pleasant and functional flow. Perhaps you've figured out how to get that flow to perform at Herculean scale. There is no doubt in my mind that this is an essential and valuable skill for anyone to learn and master.

However, there is a language you could master that teaches many of the same lessons, appears far more forgiving in terms of syntax, and has immediate broader appeal.

The language you can learn is your own.

I argue that there is an essential set of skills that intersect both with writing words and writing code. Let's revisit the process:

There's this thought I want to write.

I have finite set of words, a target audience, and, likely, a certain article length that all serve as constraints.

And... go.

Writing appears more forgiving because there is no compiler or interpreter catching your its and it's issues or reminding you of the rules regarding that or which. Here's the rub: there is a compiler and it's fucking brutal. It's your readers. Your readers are far more critical than the Python interpreter. Not only do they care about syntax, but they also want to learn something, and, perhaps, be entertained while all this learning is going down. Success means they keep coming back - failure is a lonely silence. Python is looking pretty sweet now, right?

The articles on Rands keep getting longer and longer, and as I'm finishing a piece, I worry, "Is it too long?" I worry about this because we live in a lovely world of 140-character quips and status updates, and I fret about whether I'll be able to hold your attention, which is precisely the wrong thing to worry about. What I should be worried about is, "Have I written something worthy of your attention?"

Writing is the connective tissue that creates understanding. We, as social creatures, often better perform rituals to form understanding one on one, but good writing enables us to understand each other at scale.

Now... go.

May 8, 2012

Two Universes

You wake up in a small, enclosed glass cube. There's a bed, a toilet, a radio playing music, and other bare essentials, but no door. You have no idea why you are here or what's going on.

After a few minutes of looking around your tiny space, a calm yet creepy electronic voice begins speaking. The voice explains that you're part of a testing program, and a moment later a door-sized, orange-tinged portal opens.

Portal, developed by Valve Software in 2007, is a first-person puzzle-platform game where you're running with a gun that shoots... doors. The handheld Portal gun allows you to create a doorway by placing both an entry and an exit portal. These portals can only be created on certain types of surfaces, and only a single portal pair may exist at a time. Using a combination of these portals, your beloved companion cube, and your brain, your character will experience a series of puzzles in test chambers where the goal is simple: get out - don't die.

That's the literal minimalist description of the Portal universe, but it explains little about how you'll survive that universe or what makes it fun. To understand the universe where Portal exists, you have to play it, and then you'll discover two things: it is a wildly entertaining place, and, while it is a game, it's a game full of well designed lessons that teach you how to learn.

The First Universe

Portal is a nerd fantasy. You've got this gun and when you blast a wall with it, you literally rip spacetime wide open with an entry portal. Blast another wall and there's the other half of your portal.

How. Cool.

That's the beginning of the cool and the simplest part of the game. As you progress through the increasingly complex puzzles, Portal does something even cooler. It teaches you the game, it teaches you how to improvise solutions to the puzzles, and it eventually makes you a master of the Portal gun and its associated physics -- without a single page of documentation. You learn about the Portal universe intimately, but you don't notice the learning because you're too busy playing.

Here's how...

Sandbox Learning

In addition to not knowing what the hell is going on in terms of the plot, the first time you play Portal, you have no idea how to play it. Like all games, the initial levels teach you the very basics: how to move, how to pick up an item, and how to use items to get things done. Yes, there is a heads up display indicating how to move, but it's up to you to learn. Oh look, when I put the cube on the button, it opens the door... to where? The plaques at the beginning of each level seem important, but I don't know why. Why do I feel something sinister is going down?

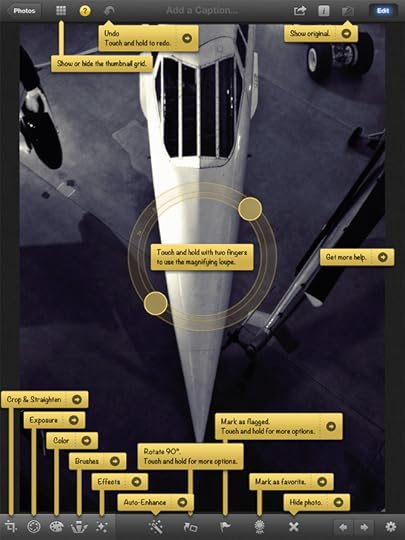

The mystery of the player not having a clue what the hell is going on is the initial incentive to learn. It's the desire to discover the story that situates the player in the Portal universe. It's a difficult balance to strike in designing a game or application. How much do you explain versus how much do you let them discover? Too much explanation and you get this:

Too much reliance on exploration and they may never discover what they can actually do. I'd include a great example of a game that was designed in this manner, but I can't and that's the point - you never played the game enough to understand and remember it.

Atomic Chunks of Understanding

Subsequent test chambers continue to clearly demonstrate additional rules of the Portal universe:

Place a cube on a big red button to activate a switch.

Portals have two sides. One end is blue and the other orange. You can enter and exit from either.

Nothing can be carried with you from test chamber to test chamber.

The discovery of these rules is paired and reinforced with increasingly complex puzzles that continue to teach the player about the increasingly foreign physics inside of Portal. What happens when I enter a portal that's on the floor, but exits on the ceiling? Which way is up? Success is not measured with points, timers, or headcrabs. Success is measured by the satisfaction you receive when you use the mechanics you've incrementally learned to solve the puzzle and exit the chamber in a not-dead state.

Testing, Testing, Testing (And the Second Universe)

As the game progresses, the increasing complexity of the puzzles introduces a bevy of hazards, including high energy pellets, goo, and turrets. The goal remains the same: get out - don't die. This is a tricky inflection point for any game: the arrival of the puzzle which is no longer a straightforward challenge, and I believe Portal's developers have solved for this moment in two ways.

First, Valve play tests the hell out their games. They are intimately aware of when a chamber is too laborious, too complex, or introduced before the player has learned the lessons they need to satisfyingly solve the puzzle in a reasonable amount of time. This is essential testing that must be performed again and again to find a delicate balance providing a sense of progress and accomplishment with just enough challenge.

This is a critical inflection point where the user is weighing the following: is the amount of investment I've made to date worth banging my head against the screen trying to figure out what to do next? An application like Photoshop doesn't do this type of testing because they know you're going to be committed to figuring out the challenge because you plunked down $700 for the privilege of owning Photoshop.

Yes, I'm going to compare Portal and Photoshop. Yes, they reside in two entirely different universes with entirely different motivations. This is about how these two universes should collide and that means what I'm really talking about is gamification. There's a reason I didn't mention this until paragraph 17 because there are a lot of folks who think gamification means pulling the worst aspects out of games and shoving them into an application. It's not. Don't think of gamification as anything other than clever strategies to motivate someone to learn so they can have fun being productive.

See, whether you're developing a game or an application, you want to your users to experience...

"The Moment"

Inevitably, you're going to need to make a split-second decision in Portal. The floor will literally be vanishing from under your feet and you'll have no time to consider your options; you will just improvise. It's these moments of well-informed improvisation that I believe are Portal's greatest accomplishment and best design. See, while you were busily having fun you had no idea that you were becoming an expert in the ways of the Portal universe. You now have experience using each of the individual tools and their behaviors to be able to combine them to handle the unexpected. The result: you are now able to effectively deal with novel and unknown situations.

It's incredibly satisfying to sneak out of a tight spot by performing an action you didn't know you could do, but created instinctively because of your experience.

That's how I want to learn. Don't give me a book; I don't want a lecture, and I don't want a list of topics to memorize. Give me ample reason to memorize them and a sandbox where I can safely play. Test me when I least expect it, shock me with the unknown, but make sure you've give me enough understanding and practice with my tools that I have a high chance of handling the unexpected.

Mastery is Well-Informed Improvisation

When someone raises their hand in that design meeting and suggests gamification, you have my permission to stand up, walk over, and poke them in the eye. But just one eye. While it's likely they are merely parroting a buzzword they heard from someone else, it's not pure buzz. Games like Portal have something to teach anyone interested in the motivation surrounding learning.

A video game has a very different goal than Photoshop. A video game is designed to be pure entertainment, while Photoshop is a tool by which you get work done. A game designer knows that if a game isn't both immediately entertaining and usable, the folks sitting in front of the Xbox 360 are going to stand up, toss their controllers on their beanbags and declare, "Screw it." Worse, they are going to tell every single one of their friends about this gaming disaster because they feel stupid for wasting their time and money on something that was supposed to be fun, but turned out to be lame. This is game death.

Photoshop's goal isn't entertaining unless you think the national pastime of bitching about Photoshop is a sport. Photoshop has no points or leaderboards because Photoshop is a tool and the perception of tools is that you must be willing to supply blood, sweat, and tears in order to acquire the skills to become any good at using them.

Bullshit.

Make a list. Tell me the number of applications you use on a daily basis where there is a decent chance that you'll end up in a foaming at the mouth homicidal rage because of crap workflow, bad UI, and bugginess. Is Photoshop on that list? Yeah, me too.

The plethora of online Photoshop tutorials demonstrate its power and its flexibility, but I believe they also demonstrate its poor design. Think about it like this: what if each time you plunked down in front of World of Warcraft, you had to spend an hour trying to remember, wait, how do I play this?

Great design makes learning frictionless. The brilliance of the iPhone and iPad is how little time you spend learning. Designers' livelihood is based on how quickly and cleverly they can introduce to and teach a user how a particular tool works in a particular universe. In one universe, you sport a handheld Portal gun that cleverly allows you to interrupt physics. In a slightly different universe, you have this tool called a cloning stamp that empowers you to sample and copy any part of a photo.

Both are concepts easy to initially understand, but eventually tricky to master. One comes from a game and another comes from an application, but the universes and names aren't important. When you master either, they both feel like magic.

Game designers have a different set of incentives to make their tools easier to learn via sandbox and atomically chunked learning. They may obsessively play test their games looking for user frustration earlier, but whether you're leaping through a portal or creating masks of transparent elements in Photoshop, both use cases strive for a moment where you can cleverly and unexpected solve a seemingly impossible problem on your own.

Game designers and application designers might exist in different universes, but there is no reason one universe can't teach the other.

April 22, 2012

10 Years

April 2012 represents the 10th anniversary of Rands in Repose. I don't normally celebrate these occasions, but serendipity has given me something to talk about.

As you might have noticed, I've recently made a few design changes to the site. I'm honored to participate in Hoefler & Frere-Jones private beta for their forthcoming web fonts offering.

Frequent readers will appreciate and understand the use of my beloved Sentinel for headlines as well as the revised header, but I believe the bigger impact is where I hope you spend most of your time - the body typeface. H&FJ's screen version of Ideal Sans, for me, is a joy to read especially on the iPad's Retina display. I can't get enough of the whimsy of the numbers (1234567890) or the calm clarity of the small caps.

If you see anything wrong, please don't hesitate to drop me a line.

10 years. 451 entries with 6500+ comments. I'd like to thank the readers of this now typographically-enhanced corner of the Internet. The only reason I'm here is because you keep coming back. Thank you.

March 12, 2012

Hacking is Important

Back in the early 90s, Borland International was the place to be an engineer. Coming off the purchase of Ashton-Tate, Borland was the third largest software company, but, more importantly, it was a legitimate competitor to Microsoft. Philippe Kahn, the CEO at the time, was fond of motorcycles, saxophones, and brash statements at all-hands meetings: "We're barbarians, not bureaucrats!"

At the time, Kahn was not only navigating the integration of Ashton-Tate, he was in the midst of moving the product suite from DOS to Windows. All the products were complete object-oriented rewrites and they were running late. Years late. At one all-hands, he explained how he wanted the company to think about itself. Recounted from a story in the LA Times from 1992:

... Kahn was reading a dense history of Central Asia a few years ago when it struck him that many of the nomadic tribes of the steppes were actually far more ethical and disciplined than the European "civilizations" they were confronting.

They were austere and ambitious, eager for victory but not given to celebrating it. They were organized around small, collaborative groups that were far more flexible and fast-moving than the entrenched societies of the time. They were outsiders and proud of it. They were barbarians.

Kahn's thinking regarding "barbarians" was prescient. It not only partially inspires Agile and other lightweight software development methods, it reinforces a theme big companies are often unintentionally trying to forget: hacking is important.

"Hackers Believe Something Can Always Be Better"

Facebook doesn't want to be a big company. Like Google before it, Facebook took the time to carefully document the reasons they were not intending to become a traditional company in their S1 filing, and while this letter is positioned to the future legion of investors, the letter is a recipe for Facebook employees:

The Hacker Way is an approach to building that involves continuous improvement and iteration. Hackers believe that something can always be better, and that nothing is ever complete. They just have to go fix it -- often in the face of people who say it's impossible or are content with the status quo.

Facebook is worried about the growth paradox, which goes something like this: The end result of successful hacking is product, and that product needs to grow by building more things. The more you grow, the more things you have, and the more you need people whose job is simply to coordinate the increasingly interdependent building activities. These people, called managers, don't create product, they create process.

Hackers are allergic to process not because they don't understand the value; they're allergic to it because it violates their core values. These values are well documented in Zuckerberg's letter: "Done is better than perfect", "Code wins arguments", and that "Hacker culture is extremely open and meritocratic". The folks who create process care about control, and they use politics to shape that control and to influence communications, and if there is ever a sentence that would cause a hacker to stand up and throw his or her keyboard at the screen, it's the first half of this one.

The growth paradox is that the chaotic means by which you found success might become distasteful to those you hire to maintain and build on that success. Once they've established themselves, they will point at the hacking and ask important sounding questions like, "What is it they are building?" or "How does this poorly defined thing fit into our overall strategy?" They will label these hackers "disruptors" and they are 100% correct.

Hacking is disruptive, and whether you code software, write books, or film movies, I believe bringing anything new into the world is a disruptive act. By being novel and compelling, the new is likely to replace something else and that something else isn't being replaced without a fight.

Reasonable people are often scared by the new. This is because reasonable people are not Barbarians and they are not hackers. They appreciate the predictable, profitable, and knowable world that comes with a well-defined process, and I would like to thank each and everyone of them because these people keep the trains running and on time. No one likes Barbarians because the Barbarian strategy is one at odds with civilization. By definition, a Barbarian, a hacker, is building on a strategy that is at odds with the majority.

It's awesome.

Facebook's letter documents its core values: focus on impact, move fast, be bold, be open, and build social value. And as I read those bullets, I see two people at the table defining them. A high impact, fast moving and bold Barbarian who couldn't care less about the Biz Dev guy who is arguing for being open and building social value.

Both people are essential to a business thriving, but only one of them knows that hacking is important.

"Where's Dieter?"

Apple solved the disruptive hacker problem by hiding it, and it starts with a question:

"Where's Dieter?"

"He moved to another project."

"Uh, he has 32 open radars and we've got two weeks until Feature Complete."

"He moved to another project."

"Ok, what project?"

"I don't know."

It happens quietly, but the projects that could be the most disruptive to the company begin in silence. Someone, somewhere has a bright idea and a handful of talented engineers are whisked off to a different building behind a locked door. Their status is "elsewhere" and their project is "need to know."

Having never sat with one of these projects, I can only infer how they work, but when you see the results, you know for certain - these guys and gals are hacking. Their projects are the definition of ambition, you've never heard their names, they are small and fast-moving, and they are outsiders in their own company. Sound familiar?

Now, I don't believe the secret projects are entirely about preventing disruption, there is a large marketing component. The return of Steve Jobs was the returning of marketing and a project being secret was less about secrecy and more about marketing. Steve wanted to be the first guy standing in front of the entire planet telling you the story: "You are not going to fucking believe what we've done."

Yes, there is internal jealously about the teams performing the wizardry that resulted in products like the iPad, the iPhone, and AppleTV. There are people wondering, Why wasn't I invited to the hacking? Yes, this did create some elitism, but, for better or worse, the secrecy kept this discussion out of the mainstream.

The secret projects at Apple are institutionalized hacking. They are places of elsewhere where the engineers don't have to worry about being Barbarians because everyone there knows hacking is important.

Unintentionally Forgetting What It Took To Get You There

The story of every company begins with a clever hack. Pick any company, read its history, and I'm pretty sure there will be a well-documented origin story that will define its beginning and involves someone building something new and possibly of unexpected value. What isn't documented is the story of every moment before where everyone surrounding the hacker asked, "Why the hell are doing you that?", "Why would you take the risk with so little reward?", or "Why are you wasting your time?" What's not documented are the nine spectacular failures the hacker survived before they built one success.

The well-intentioned people who arrive after the initial success of the hack don't know of a world without it. They assume its existence and are tasked with growing the company around it. Don't for a moment think I don't value these people, because I happen to be one of them, but I am also intimately aware that the people who grow the company are not same people who found it.

A healthy product company is, confusingly, one at odds with itself. There is a healthy part which is attempting to normalize and to create predictability, and there needs to be another part that is tasked with building something new that is going to disrupt and eventually destroy that normality.

Failure to create some form of predictability will result in chaos. Failure to create some sort of well-maintained Barbaric chaos inside the company guarantees that a fast-moving, ambitious, risk-taking and ruthless someone else - someone outside the company will invade, because they know what you forgot: hacking is important.

March 3, 2012

A Dependable iPad

Apple is maintaining a difficult balance with the iPhone and the iPad. On one end, they appear to want to release each product yearly. The first three iPhones were either announced or arrived in early June, until the iPhone 4S was announced in early October with initial shipments two weeks later. So far the iPad debuts in the March/April time frame. This yearly cadence mirrors the fashion industry, where each year something new and beautiful to covet is introduced.

However, theses devices are expensive. In the US, the carrier supported 32GB iPhone 4S is currently $299 and the 32GB iPad 2 is $599 - both prices feel well above your average impulse buy. This is why I think it's no mistake that the two devices' release dates are as far apart as possible on the calendar given the yearly release cycle. This gives you the maximum amount of time to forget how much money you just plunked down on the latest bright'n'shiny.

It's a strategy that has normally worked brilliantly on me, until the arrival of the iPad 2. It wasn't that I didn't covet the slim stylings, I just didn't feel like I'd yet gotten my money's worth with my original iPad by the time the second iPad arrived. When it did, I carefully held it in my hands, drooled a bit on the black Smart Cover, and considered the question, "Is it worth it?" and discovered the answer was, "No". Interestingly, this answer did not change over time. Perhaps a function of the iPad's price point? Release date? Feature set? I don't know.

What I do know is that barring an unexpected post-Steve-Jobs apocalyptic design disaster, there is no way I won't be purchasing the forthcoming iPad 3, and following is a prioritized list of the features I'm looking forward to considering.

Features I want:

Retina display. You generally hold the iPad farther away from your face because of the larger form factor, which is why I don't think I notice the difference switching between the iPhone's Retina display and my iPad. But I'm fully expecting to be dazzled by the shine of Retina's double pixel density. I believe the Retina display will be your Holy Shit moment with the iPad 3. This will be the feature you'll be showing your friends.

Snappiness. My measure of CPU and graphical processor speed is completely based on feel. The test is, "When I perform a common action is it faster or slower?" Slightly faster is not snappy. Snappy is measured in a word: "Whoa".

As much battery as possible. Rumors are pegging the iPad's shell as being ~0.81mm thicker than the iPad 2. My hope and belief is that every single millimeter is being stuffed with additional battery. I'm fine with a reasonable amount of heft as long as I'm getting impressive battery life. Using the initial iOS for the iPhone 4S, it was clear that it had a shorter battery life. It's better with later iOS releases, but my impression is that it's still not as good as my prior iPhone. My fear is that the combination of additional processing and graphical power is going to weigh heavily on battery life. Via whatever my final usage patterns are, if I need to charge the iPad more than once a day, I'll be disappointed.

Features I'm interested to consider:

The absence of a physical home button. My son just explained the possible appeal of virtualizing the Home Button. It's so that no matter how you are looking at it, there's a home button right under your nose. I use the Home Button on the iPhone all the time for a very basic maneuver: I reach in my pocket and feel for the front button on the phone. The Home Button instantly orients me to the location of everything else on the phone, whether it's the headset jack or the camera. I don't have the same need with the iPad, and, in fact, I like the idea that Home may always be in the same place. I would not say the same thing if the button was being removed from the iPhone unless some type of haptic magic is being deployed, which is entirely possible.

Cost. To date, Apple seems very happy sticking with their Good, Better, Best pricing structure, with the only variables being storage and 3G - pricing was unchanged for iPad and iPad 2. There are two obvious pricing pressures on iPad 3: component prices and competition.

Component price. Clearly the hardware necessary to provide the Retina display is going to cost more. Same with a new CPU and all the other whiz bang Apple shoves into the enclosure. The question really is: what's the total cost to Apple given that existing component prices continue to come down, combined with Apple's ability to write monstrous checks to the tune of, "We don't want lots of that component, we want all of it... for, like, ever, and if you're not interested, well, we'll just go build or buy our own factory. Your thoughts?"

What's the delta on cost to Apple? Even with all the purchasing muscle, my guess it's still higher.

Competition. The tablet space is Apple's. Amazon's had a foothold with its recent impressive land grab of market share in the space, but I'm very interested to see what happens in the post-Christmas quarter where, oh yeah, the iPad 3 shows up. Will Apple competitively price the iPad 3? Absolutely, but Apple is defining this category and, as such, they are defining - not reacting to - pricing.

My only prediction: Wi-fi pricing stays exactly the same at $499, $599, and $699. If there is a going to be a price increase it will be for the 4G units, and, as you'll see below, I'm not considering that option. Faced with increased component costs and increased competition, I don't think Apple is going to blink.

As for my ideal price point, that's better answered by...

Affordable storage. I've only run into storage issues on my iPhone primarily because of my Instagram addiction. This was mostly solved with my 32GB iPhone 4s. As for the iPad, its 32GB are fine, and if we're putting it all in the cloud, I'm not likely to bump to 64GB (or higher) unless it's price effective. Given my pricing guesses above, I'll happily pay $599 for my iPad 3.

Acceptable weight. The weight of my current original iPad is only an issue when I'm in bed on my back with the device on my chest. I'm likely watching Hulu and after a couple of episodes, I begin to feel the iPad's weight. This is the only time I've noticed the iPad's weight and I've taken it all over the world. The iPad 2 was almost 80 grams lighter than its predecessor, and in my informal poll of friends, they haven't complained about weight. So, close to that, ok?

Features I don't think I care about (but could be convinced otherwise):

4G. At the house, I have a Verizon MiFi and it's jaw-droppingly fast and also a complete power hog. I'm regularly getting 10Mbs downstream and I live in the middle of nowhere where Verizon fleeces me for crap DSL. I've never considered the data version of the iPad because the majority of the time I need my iPad there's either wireless nearby or my iPhone serves whatever mobile need I have at the moment. Besides, I want that larger battery powering all those pixels and processor cycles.

Camera. The iPhone is a clear replacement for a point and shoot camera. The iPad's is not. The use case for the iPad's camera is FaceTime, and for me and I'm likely in the minority here, FaceTime is a classic You-Gotta-See-This-Once feature. You demo it once and never use it again. The line I draw for the cameras is "it can't be crap."

Siri. Sure, ok.

My final wish is the hardest to define. I am not regularly using my iPad for anything substantive in my day. I use it, but I don't depend on it. Whereas if my iPhone isn't within arm's reach, I get twitchy. I don't know what combination of features might make the iPad more attractive, but I'm certain that a dose of snappiness, a plethora of the pixels, and the three subtle details that no one will predict but everyone will love could make a difference.

(Disclosure: I own Apple stock and I worked at Apple for the better part of a decade, which fulfilled a dream I had since I was a kid.)

February 29, 2012

A Precious Hour

I am told that the manner by which others understand that I am busy is when my writing coherence suffers. This primarily occurs in email when whole words are dropped, sentences become jumbled, and logic falls on the floor. Rands, I literally did not understand what you were asking in that email.

Poorly written emails are an early warning of intense busy. Yes, I lack the time to proofread an email, but the mail is sent. At least I accomplished something. The step beyond this is when shit is truly falling on the floor, and while shit on the floor is professionally unacceptable, there used to be a point of irrational pride in my head during this situation: Look at me, how important I must be, with all the... busy.

It's this irrational pride I want to examine because hidden inside of it is an insidious red alert situation.

The State of Busy is Seductive

7:15am. I sit down at my desk, fire up my calendar, and examine my day. Six meetings starting in 45 minutes. All are compelling, all are likely to lead to progress. Good. Switch to Things and examine the backlog. I've got 45 minutes and 23 open tasks. Which of these should I prune? Which of these stay... Say, I've been meaning to call Joe for a week. I'll call him now.

7:25am. Joe and I are on similar morning caffeination plans, so the call is high bandwidth. We're done with our three topics in 10 minutes, and I'm now sporting the rush of not just completing a task, but completing it at speed. I need to parlay this intense rush -- what's next? Where else can I exceed my productivity expectations?

7:30am. Ok, now I'm rolling. I've skimmed my email and as I think of them, I'm writing tasks on a paper next to my keyboard, because I've somehow convinced myself that writing the task down on paper is faster than putting it in Things. (Huh?) No matter - all hail the rush of getting things done. The cycle continues. Another task is knocked off, a sip of coffee, and now I'm headed into my 8am with a head full of palpable busy.

The Zone is a well understood mental state where you are fully dedicated to the problem in front of you. First, you take the time to get the complete state of the problem in your head, which then allows you to make massive, creative mental leaps using a precious type of focus that is fleeting. In the 45 minutes leading up to my 8am meeting, I did not get in the Zone. However, don't tell my brain because I've worked hard to create the illusion that I am: massive amounts of data flowing about, a sense of purpose, and scads of coffee, but I am not in the Zone. I'm just busy.

The Faux-Zone

When an engineer becomes a lead or a manager, they create a professional satisfaction gap. They've observed this gap long before they became a lead with the question: "What does my boss do all day? I see him running around like something is on fire, but... what does he actually do?" The question gets personal when the now freshly minted manager begins to understand that life as a lead is an endless list of little things that collectively keep you busy, but, in aggregate, don't feel much like progress.

The positive feedback an engineer receives in the Zone is the sensation that you literally performed magic. From the complete problem set in your mind combined with your weapons-grade focus, you build a thing that you immediately recognize as disproportionately valuable. And you see this value instantaneously - that's the high.

I believe that leads and managers are forever chasing the high associated with the Zone, but rarely achieve them because their job responsibilities are in direct contradiction to the requirements to achieve it. We often lack the time to have the intimate knowledge of a problem space because we rarely have 10-15 minutes free to consider it.

The amazing set of skills we've built to compensate for this utter lack of context is impressive. You would not believe how many times your boss has walked into a meeting with absolutely no clue what is supposed to happen during that meeting. Managers have developed aggressive context acquisition skills. They walk into the room and immediately assess whose meeting it is, listen intensely for the first five minutes to figure out why they're there all, while sporting a well-rehearsed facial expression that conveys to the entire room, "Yes, yes, I certainly know what is going on here".

Like these context acquisition skills, we've also convinced ourselves that we have built a mental process that gives us the high that we're missing in our interrupt-driven lifestyles. We've created the Faux-Zone.

In my 45 minutes before my 8am meeting, I did not enter the Zone, but I am in the Faux-Zone. It is a place intended to create the same rewarding sense of productivity and satisfaction as the Zone, but it is an absolutely fake Zone complete with the addictive mental and chemical feedback, but there is little creative value. In the Faux-Zone, you aren't really building anything.

A Precious Hour

As a frequent occupant of the Faux-Zone, I can attest to its fake productive deliciousness. There is actual value for me in ripping through to my to-do list. I am getting important things done. I am unblocking others. I am moving an important piece of information from Point A to Point B. I am crossing this item off... just so. Yum. However, while essential to getting things done, the Faux-Zone is not a replacement for the actual Zone, and no matter how many meetings I have or how many to-dos are crossed off... just so... the sensation that I am truly being productive, that I am building a thing, is false.

My deep-rooted fear of becoming irrelevant is based on decades of watching those in the tech industry around me doing just that - siting there busily doing things they've convinced themselves are relevant, but are just Faux-things-to-do wrapped in a distracting sense of busy. One day, they look up from their keyboard and honestly ask, "Right, so, what's Dropbox?"

Screw that.

Other than spending time with my family, my absolute favorite time of the week is Saturday morning. I sleep in a little bit, walk upstairs, start the coffee process, and wander over to the computer. There's a Dropbox folder titled "Latest Rands Articles" and right this moment there are 65 articles in progress there. After a brief stumble of the Internet, a precious time begins. I have precisely the right music on, in the center of my screen is a wall of words, and in that moment I'm decidedly not busy, I'm not working - I am building a thing and I need this time every single day.

Starting at the beginning of February, I made a change. Each day I blocked off a precious hour to build something.

Every day. One hour. No matter what.

Every day? Yup. Including weekends.

A hour? Yup, 60 full minutes. More if I can afford it.

Doing what? The definition of "building a thing" is loose. All I know is that I get rid of my to-do list, I tuck the iPhone safely away, and if there is a door, I close it. Whether it's an hour of Choose_your_own_adventure Wikipedia research, an intense writing session, or endlessly tinkering with the typography on the site, it's an hour well spent.

No matter what? Since I've started I've had roughly a 50% success rate of actually getting to my hour. The excuses are varied, but the data is compelling. Even at a 50% hit rate, I've written more, I've tinkered more, and, most importantly, I've spent over eight hours this month alone exercising the part of my brain I care about the most: the part that allows me create.

What would you create if you had eight uninterrupted hours - every month?

An Insidious Situation

There is a time and place for the purposeful noisiness of busy. The work surrounding a group of people building an impressive thing contains essential and unavoidable busy and you will be rewarded for consistently performing this work well. This positive feedback can feed the erroneous assumption, "Well, the more busy I am, the more rewards forthcoming." This is compounded by insidious fact that part of being busy is you aren't actually aware that you're busy because you're too busy being busy. You have no internal measurement of the amount of time you've actually spent being busy.

In my precious hour, I am aware that it is quiet. During this silence, maybe nothing at all is built other than the room I've given myself to think. I break the flow of enticing small things to do, I separate myself from the bright people on similarly impressive busy quests, and I listen to what I'm thinking.

Every day, for an hour, no matter what.

February 28, 2012

Interview: Scott Berkun

My introduction to Scott Berkun was his amazing talk at Webstock 2008 on the Myths of Innovation, based on one of the three books he's published in the last decade. I remember his talk not only because of the compelling content, but because he eschewed the traditional get-to-know-you slides in his presentation - he jumped right in.

His latest book, Mindfire, is a self-published collection of best essays from his invaluable weblog.

RANDS: After many years out of the game, you recently started working at Automattic. Why the return to industry? Was this always the plan?

BERKUN: I have always hated arrogant author/consultant types who had either never done the job themselves, or hadn't in decades (See How to Call BS on a guru). After writing 3 books and being a speaker for hire for a decade, I was becoming that guy and I knew eventually I should get back into the fold and see how much of the advice I give people I practise myself. The opposite of a sabbatical. The awesome Matt Mullenweg approached me about Automattic, and as I used WordPress for my blog, it seemed a great way to return to the front lines for a time. Since 2010 I've managed a team of designers and developers working on WordPress.com.

After being out of the game for a decade, what changes (if any) did you notice with the software development teams?

The important things are the same: do we trust each other? Are we motivated? Are there clear goals? Can we move roadblocks out of our way? As simple as those four things sound, they're rare. Always have been and always will be. As a leader, my job is to make good decisions, and if I do that, all four of those things become true. I did notice some superficial things that have definitely changed: namely that I'm old. My jokes and references get blank stares. But that's recoverable. If you watch enough YouTube videos to catch up on the references du jour, you do fine.

Your most recent book, Mindfire, is self-published. What was the reasoning behind this decision? And what were the most valuable lessons learned?

The best way to learn is to do. I'm going to be writing books as long as I'm alive and I need to learn all I can. Doing something yourself forces you to learn every angle. Even if I never self-publish again, the way I can talk to any publisher is different: I know more. The big lesson is that self-publishing is easy. The technology is amazing. Anyone can easily publish a book for not much money. There are no excuses. The real challenge is, as it always has been, writing a good book.

How has the conversation with your publisher changed?

It hasn't changed much, which is nice. O'Reilly Media has been very cool. Joe Wikert, General Manager at O'Reilly, interviewed me in a video cast, where we had a frank chat about all the related issues. Why I did it. What I learned. What I'd recommend to authors and publishers. How cool is that? He even helped plug Mindfire.

The book is a collection of essays from your blog. How did you go about picking the articles to turn into chapters?

Every 4th or 5th post on the blog has asked big philosophical questions in a fun way. Book smarts vs. Street smarts, Hating vs. Loving, or How to detect BS. I wanted to take all those posts that asked big and fun questions and fit them into a single volume focused on that kind of thinking. We made a long list of candidates, and then removed ones that didn't fit together or had no easy place in the flow of essays.

Your title at Microsoft was program manager. I think there is a lot of confusion about this role -- what's your best definition?

It's a glorified term for a project leader or team lead, the person on every squad of developers who makes the tough decisions, pushes hard for progress, and does anything they can to help the team move forward. At its peak in the 80s and 90s, this was a respected role of smart, hard driving and dedicated leaders who knew how to make things happen. As the company grew, there became too many of them and they're often (but not always) seen now as annoying and bureaucratic. In simple terms they are team leaders; good, trusted sergeants near the front lines.

Do you think there is a cautionary tale in the rise of power of the project/program manager relative to Microsoft? How might you prevent that in other companies?

The short answer is too many cooks. The long answer is, in the case of Microsoft and most successful companies, decay and bloat are inevitable. The story of PMs at MSFT is just part of that. You can't be lean and have 100,000 employees at the same time. Some roles don't increase in value as you add people, particularly meta-roles (e.g, leads, managers, etc.) Somewhere along the way the ratio of PMs to engineers got out of control, and as soon as PM types were in charge of controlling that ratio, it's not a surprise no corrections were made. Over a few years it becomes part of the culture, and all the developers expect PMs to be there to protect them or do the annoying work. It becomes symbiotic. In some cases, it's codependent, but not always. The basic rule I was taught, which has been forgotten, is make the tough choices. If you can't make decisive choices, you're lost. I bet if we asked most PMs at Microsoft (or managers at any large company) if there are too many PMs, they'd passionately agree. The problem and the solution is all right there.

At what point/time/team size/inflection point do you think a team needs a program manager?

Once you have more than a handful of developers, leadership activities emerge naturally or productivity drops. Who is the tiebreaker in tough arguments? Who figures out how everyone's work will fit together best for users? Who makes the best trade-offs among time, resources, and customers? Who has the clearest vision and articulates it the best? Who knows how to say NO? A program manager is an encapsulation of many of those intangible leadership and decision-making skills into one person.

According to Wikipedia, you have a goal to fill a shelf with books that you've written. First, what is the origin of this story? Also, how many books does it take to fill a shelf?

When I quit to try and be a writer, I needed a visible goal. Something I'd see all the time. A book is hard work, but in the grand scheme it's nothing: I want to die with a body of work, and having a long-term goal makes many short-term choices easier to make. I cleared the shelf closest to my desk and the only thing I'm allowed to put on it are books I've written (4). I haven't measured it as it's mostly empty, but I suspect I need to write 25 books to fill it. I believe I'm entirely capable of this challenge; it's purely a matter of priorities and I hope the empty shelf helps me prioritize my working life.

I'm always curious about a writer's process. Can you walk me through the process of how an idea turns into an article?

As a fun cheat answer, I made a time lapsed video of this process, with audio commentary. It's all there.

What is your perfect writing environment?

I'm not that picky - with the right music I can concentrate anywhere. I work mostly in my home office, but I can write in a coffee shop, too. If I'm working on a book I need more desk surface area for notepads, books and things.

What's the next book?

All I can say is it's something different :)

February 19, 2012

When the Sky Falls

A few years ago I wrote a piece that romanticized the state of the sky falling. The article is not about fixing disasters, it's about preventing them, but no matter how much you prepare, disasters happen.

The romance surrounding disasters is history speaking. When the disaster shows up and you see it, no one but you knows that you want to throw up. That's your brain releasing a complex chemical cocktail that is physically and emotionally preparing you for the most sensible course of action - making a fucking run for it.

But, strangely, you do not run.

Having watched, participated in, and created a bevy of sky-falling situations in my career, I take the process I use for managing these situations for granted. It feels like I'm working on pure and spontaneous instinct, but these are honed instincts that I've built and refined over a great many DEFCON 1 disasters that I've had the unfortunate pleasure of attending.

This is my documentation of the process, and I sincerely hope you never have to deploy it, but I'm pretty sure you will. Before we start, a few assumptions and notes about this process:

This is not a solo disaster. It's not just you, it involves a large group of people wrestling with a complex disaster , featuring different politics and motivations with an unknown root cause.

No matter how much I sit here and EXPLAIN IN ALL CAPS THAT THIS PROCESS WORKS, you're going to skip at least one of the following four steps. That's cool. Each section includes a handy "This is what happens when you skip this section" addendum so you clearly understand the magnitude of your omission.

I'm going to describe this process simply and serially, but in reality these steps overlap and often run in parallel.

Oh yeah: there's a good chance this disaster is your fault.

Let's begin.

STEP NUMBER ONE: The Situation in the War Room

Your first job is to understand absolutely everything you need to know about the current state of the disaster - you are developing a mental model. Ideally, I want to be able to draw a complete picture for everyone about whatever the hell is currently happening. I need white boards - lots of them. I need a War Room.

The War Room is a base of operations. The requirements are simple: enough room to hold a quorum of people, a table, chairs, and lots and lots of white boards and markers. In this room, you are going to begin the immediate task of research, information gathering, and assessment. Every single person - everyone - who has any relevant knowledge about the situation is now going to parade through the War Room and you're going to capture and triangulate all of their knowledge.

The intent of the War Room is to break everyone from their flow. The War Room includes a menagerie of people coming in and out, empty pizza boxes and Red Bull cans, and white boards full of indecipherable scribbles. It sends a clear message: the status quo is not presently working.

As the people start streaming in for the inquisition, remember that this first step is data collection, not problem solving and not judgement. The hardest part of this step is not to jump when you think you see a place you can start moving. That! That! That! We need to fix that! It very well might be the right move to fix that, but you don't even know how much "that" there is, yet.

The initial goal during this step is information acquisition, not action. Each time you take action with incomplete data you risk stoking rather than extinguishing the disaster fire. And, by the way, this type of lack-of-foresight hyper-reactive mode is likely what got you here in the first place. The War Room is a place to focus on gathering a breadth of information first, then depth, so you can answer the question: "Do we understand the situation?"

For me understanding comes in three forms:

The picture I begin to draw repeatedly on the white board starts to represent a realistic picture of what has actually occurred.

A list of additional research, work, and potential next actions is developed, revised, and iteratively prioritized (but not yet acted on).

After much #1 and #2, I'm looking for a very precise moment. It always happens at a different time, but it is distinct. It is the moment I have the glimpse of a theory. This... is what we need to do.

What happens if you ignore this. A surprisingly number of smart people skip this step. They believe that they can both assess and solve the problem at the same time. This is akin to saying, "I will solve a math equation that I can only half see." It's absurd, but it's precisely what someone does when they start making critical decisions with incomplete data.

Action feels like progress, but undirected action is not progress, nor is it a plan. You're going to barge into the office and start barking orders because that is what everyone expects, but if your orders are not shaped by what you're really attempting to do, you are just scurrying people around aimlessly. Yes, you get lucky. Yes, everyone breathes a sigh of relief when you show up with your impressive sense of purpose, but in my experience when my direction doesn't map to intent, I'm usually getting no closer to propping up the sky.

STEP NUMBER TWO: The Bet Your Car Perspective

With your new found confidence that you've fully described the problem in front of you and have a semblance of a fix, my timely buzz kill is this: I am 100% absolutely certain that you've missed something essential in your first pass. There are two ways to discover this: you can jump straight into the next step and discover this absence at the most inconvenient and credibility-destroying moment, or you can check your math. To do this there are two phases:

#1 Vet your model with, at least, three qualified others. These are people who were not directly involved in Step #1 and who are people who don't need to understand the particulars of the disaster, but can appreciate the broad strokes because they've been there, and have no issue with telling you how screwed you are.

The joy that occurs at the end of Step Number One is the discovery of a fix. This moment of illumination is gratifying because it's the first time you believe there is a chance the sky can be propped up. Bad news: confidence is not a plan either. This situation is very common with software developers who are fixing bugs. They look at the bug description, write a few lines of code, rebuild, and, viola, it's fixed, because when they reproduce the exact steps of the bug, the bug no longer occurs. They have no idea that this small change in the import export code will also have unintended side effects on other file operations.

Having a solution where all the implications of the solution are not understood is not a fix. You must take the time explore all the implications, and in my experience this takes longer than it took to come up with your plan.

#2 Once your qualified others have discovered those gaping holes and unintended consequences that are guaranteed to exist in your fix -- your model -- you need to throw the current version on the nearest whiteboard in the War Room with the folks who are responsible for the work that's going to go down over the next few days and ask the same question: Does this picture, this list, make sense?

This is yet another error correction pass for gaping holes. It's also a pass on prioritization, but most importantly, it's an assignment of ownership.

One of the leading causes of sky falling situations is distributed ownership, and as a strategy distributed ownership seems very humane. We're going to put the right people on the right problems. We're going to empower the most qualified people to make their own decisions regarding their local problems because they have local knowledge and can make the best decisions using this knowledge. As a human being and a nerd who has an intense allergy to being told what to do, this model of distributed ownership appeals to me. I imagine small teams of bright people empowered because they feel they control their destiny.

A sky falling situation exists not because of a single failure on one team. It's a collection of multiple large and small mistakes on many teams that snowballs into an unexpected worse case scenario. Teams of people succeed and fail at scale. A likely major contribution to your current disaster is the fact that multiple well meaning and fully informed people looked at an emergent disaster and thought, "Well, someone who is not me is going to handle this, right?"

Since you're the person who is racing to work while panicking about the sky falling, I'm going to call you what we called these folks during my tenure at Apple: the Directly Responsible Individual or DRI. This name clearly describes the person who is directly responsible for whatever the situation might be and it's a person. It's not the Directly Responsible Group of People With Good Intentions Who Are Attempting to Feel Good by Building Consensus But Who Are Mostly Wasting Everyone's Time. It's an individual who is owning the entire situation.

However, as the DRI, the person who is most likely to be yelled at, your job is to be accountable. Your job is not to own all of the work, which is why the last part of this step is to put a proper name next to each and every task, and, as much as possible, this name should not be yours. When you're done with this assignment and someone in the War Room asks, "Hey, why isn't your name on the list?" Your answer is, "Because I'm the one making sure this whole thing is moving forward and I'm the one who gets fired if it doesn't."

What happens if you ignore this. There are a variety of skippable parts in Step Number Two, but I'm not worried that you don't have an initial plan or that you're incapable of pulling trusted others in to distribute the load. The part that has screwed me the most is failing to understand all of the implications of my theory.

A former boss used to put this into clear perspective, "Do you understand all of the implications of your plan?" Yes, I do. "Give me your car keys." Wait, what...? "Would you bet your car on the viability of your plan?" Right, yeah, let me do one more pass.

STEP NUMBER THREE: Constant and Consistent Sky Propping Pressure

When the sky is falling, everybody is watching. Everybody wants status an hour ago. Everybody is talking to everybody else about the state of your sky-falling situation, which means the Grapevine is actively working against you. The amount of fear, uncertainty, doubt, and outright lies generated about what's actually going is impressive.

I'm assuming that you've got a credible plan that you've carefully vetted with others. I'm assuming you've assigned the work to competent folks who have a sense of ownership of their respective parts of the plan. I'm assuming the War Room is abuzz with the action defined by the plan. While all of this going on, your job is internal public relations.

As soon as I have something to report, I send the report to everyone who wants to know. If you walk by the War Room, poke your head in and ask, "What's up guys?" I add you to the distribution list. You're going to get every update until you beg to be removed. Anyone who mails me any random question -- they're on the list. The game here isn't just over-communication and Grapevine eradication, I'm still worried I missed something in the plan, and the status spamming is another another means of vetting both the plan and the progress.

How often do I send status? It's a judgement call based on progress relative to the beginning of the disaster. The better the legitimate progress, the fewer the updates. It moves slowly from hourly updates to daily updates and ultimately to weekly ones, which is when I start thinking about tearing down the the War Room.

What happens if you ignore this. It's hard to imagine someone not regularly broadcasting clear, demonstrative, measurable, and consistent progress. Maybe because you're still deep in research and don't yet have a theory and you don't want to call attention to that fact? Maybe there hasn't been significant progress on anything since your last update? You still send status. The message you send by consistently keeping the folks who care up to date is not: "We've made unique progress or we have a theory," the message is, "We are applying constant and consistent pressure on propping up the sky."

The Elusive Step Number Zero

I'm reading an early draft of this piece and it still feels like there's romanticism about this process. Look at me, Captain of the War Room, I'M GOING TO SAVE THE WORLD. There's nothing romantic about this situation. There's no glory in propping up the sky because, chances are, you and your team are partially responsible for this situation and depending on the severity of the disaster, there's a good chance you could get fired. Even if you fix it.

There's a fourth step to this process that I've confusingly labeled as Step Number Zero. I've put the first step last because I believe it's the most important part of this process. I've put the first step last because if you're able to confidently answer it, you'll greatly increase the chances that you won't repeat this disaster in the future. The question is: What, precisely, are you trying to do?

It seems like a dumb and obvious question at this very moment, but right now you're chilling with your iPad in the coffee shop. You've just taken your third sip of that half-caf quad-shot latte and you don't have a care in the world. If the sky was actually falling, you'd be racing to work, breaking speeding laws, and frantically thinking, How am I going to unfuck this situation?

Unfucking this situation is a sensible and obvious outcome, and while you're driving 105 miles an hour down Highway 280 to the scene of the crime, I will repeat myself: What, precisely, are you trying to do?

It's a hard question to effectively answer when people are yelling, but phenomenal answers sound like:

We need to demonstrate to this customer that we are capable of exceeding their expectations.

We need the people who depend on us to trust that their faith in us is not misplaced.

We need the Planet Earth to understand that we aren't evil.

You will notice that none of these answers read "unfuck the situation". When the sky is falling, like I've said before, immediate action feels like precisely the right course of action because HELLO THE SKY IS FALLING. But there is a well defined reason for this situation, and it's likely you won't know the reason for a while. It's agonizing, but my advice is to not make any decisions on course of action until you have at least a credible answer to this question.

In the face of disaster, it's the wise person who does not act until they know. Unfucking the situation is a bandaid, understanding what you're truly trying to fix is a cure.

Michael Lopp's Blog

- Michael Lopp's profile

- 144 followers