Deborah Robson's Blog, page 9

December 22, 2012

Finding the right direction

Sometimes it's hard to find the right direction to go on the road, even though the pavement is smooth enough that riding is easy.

Then a marker appears. This is a lane. But is it heading the right way?

Sometimes the directional hints seem to be correct but not clear. Is this path worn out? Was it meant for someone else?

At other times the signs are well defined but confusing.

But now and again the markers are completely unambiguous: Yes, this is your path. Keep going this way.

December 21, 2012

UK visa saga, continuing

I spent a lot of last week working on how to get a visa to teach short, small-group, low-key workshops in the United Kingdom. A friend wrote, "It seems it shouldn't be that difficult!"

That made me laugh, because it's turning out to be one of the most bureaucratically difficult tasks I've ever encountered (and I've had my share of bureaucratically difficult tasks). This type of activity falls between the cracks of what the Border Agency and immigration generally handle.

As the situation stands, I can't find a viable option. It's true that every time I visit the Border Agency site for details, I find additional categories that end up not being appropriate. The information for any single category has to be pulled from a lot of different pages on the site, then assembled like a puzzle. I'm never sure I've got it all—although I'm always pretty quickly assured that the choice I'm trying to figure out doesn't apply. Then again, the rules just changed on December 13. I don't think the changes affect anything I've been looking at, but I can't be sure.

There is a "permitted paid engagement visitor" classification that looks promising, but that requires sponsorship by an entity as large as a university (or similarly well-established organization in a different arena), and the criteria for qualifying are extremely unclear. In fact, in some places the information for permitted paid engagement visitors says no visa is required, and in other places it says one is needed. Even in the not-required advice, a visa is recommended. Getting one seems prudent, to be sure.

The other visa type that is a leading contender (Tier 5, migrant worker, creative/sporting) is constructed to accommodate music and sports stars, and other people who will participate in large, well-funded events. They require a sponsor who has the appropriate license, at a cost of around £500 (about $808), plus a fee for assigning a certificate of sponsorship to an individual, £13 (about $21). Once the license has been obtained and the certificate has been assigned, the fee for each sponsored individual is either £194 or £661 (about $314 or $1,069), depending on where and how the application is submitted (submitting online from outside the country is a less-expensive alternative). Prorated over the 12-month (normal) to 24-month (extended) working period allowed with that visa, that might be sustainable. For a week or so of work, it's not.

I don't know of a guild or local sheep-and-wool festival that can handle the initial expense and paperwork—even a collection of guilds and fiber festivals would be challenged to pull it off. (Here is a PDF explaining what's involved in becoming a sponsor.) And then the teacher needs to be paid for the work performed, and travel and accommodations have to be covered.

Visa advisers exist, in both paid and nonprofit versions, but they have no expertise relevant to this situation. Their clientele needs help with issues like permission to immigrate in order to marry; to immigrate permanently as a refugee or family member of previous immigrants; and so on.

The situation we are talking about requires a policy decision pertaining to cultural exchange. The Border Agency implements the rules, but does not establish them.

While the Embassy guidelines say that they do not deal with visa questions, this is not a matter of an individual visa problem but, as a friend pointed out, of policy relating to cultural and scientific interchange. The questions pertain more to the fiber (or general arts) community than they do to me as an individual, although obviously the individual situation is what makes the policy problem clear and puts me in a position to ask.

Here's the gist of my inquiry, which I supported with an introduction to my background, publications, and other credentials (they do add up over the decades), a brief bio, and other details:

___

I’m planning a . . . research trip to the United Kingdom for fall 2013, and a number of people have asked me if I would be willing to teach a few workshops while I’m there. I am writing to you at the Embassy because I am stumbling across concerns relating to “cultural relations,” which are stated as part of the ambassadorial responsibilities.

. . .

The primary purpose of my trip is research. . . . If I were to teach to the extent that my research is compromised, the trip would be a failure; if I am unable to teach and spend my entire time in research and visiting friends, it will be a complete success. . . . I will be self-supporting throughout, except that I would need to be paid for any teaching (for both personal and legal reasons).

In extensive reading of the Border Agency information, it appears that there is no visa option that would allow me to give talks and teach workshops of the types that are being requested:

of short duration (between one hour and five days, most likely half- to three-day workshops),

to small audiences (generally between six and twenty-four people, although possibly more for a slide-talk),

under the auspices of local groups with minimal resources (guilds of handspinners, weavers, and knitters; or local smallholders’ or sheep-and-wool festivals).

Here are the closest-to-possible visa categories, and why they don’t seem workable for the situations in which I’m being asked to teach:

The Tier 5, Creative/Sporting, visa requires a sponsor license, which is vastly beyond the means of the groups that would like me to teach for them. [NOTE for the blog: This is the £500 + £17 + £194/£661 option.]

The permitted paid engagement visitor option requires collaboration with a U.K.-based organization of greater stature than a local gathering of fiber artists (who likely get together in each others’ living rooms or a local shop) or a small holders’ fair. (Criterion for this category: “must be invited by a UK higher education institution or UK-based arts or research organisation. . . [or] a UK-based arts or sports organisation or broadcaster.” Those are large, formal organizations.) For this option, even if it were otherwise workable, it’s not clear whether its thirty-day limit refers to the number of days of paid engagement or the entire visit (the latter would not allow me adequate research time). [NOTE for the blog: This is the one with very unclear parameters. It would be possible to arrive at the Border Agency and be turned back if the paperwork, undefined, is not in order.]

The academic visitor choice doesn’t pertain. As an independent researcher, I do not have an academic affiliation. In any case, my short-stay trip would be much more abbreviated than this category seems intended to accommodate.

At this point, I am on the verge of giving up on the possibility of teaching. I can, as originally intended, limit my trip to research, and will respond to inquiries about workshops or talks with a note saying that the visa situation makes it impossible for me to teach, even though I love sheep and wool (especially British sheep and wool) and it’s a delight to share what I know with other people who care about these topics.

___

This overall situation causes a great deal of trouble in the fiber community and is restricting the intellectual and cultural interchange among its members. I know that similar issues affect citizens of other countries who want to come to the United States to teach, but this is one aspect of the problem that I can work on. While it does affect me, I am not dependent on any specific outcome. If I teach: good. If I don't: my research can continue—no visa is required for that. By endeavoring to find a way through the thicket, I may help clear at least one pathway for sharing knowledge within what is increasingly becoming a global fiber community.

(I wrote a letter in order to effectively present the information. I couldn't figure out a way to do it succinctly on the phone, and there are no e-mail contacts. A good, old-fashioned letter seems better anyway. I didn't handwrite the whole thing. I want the people I'm approaching to be able to read it easily! And to take their time considering and, I hope, responding to the issues I am raising.)

Teaching across international boundaries is very important to the transmission of the skills involved in traditional textile crafts, and to our ability to work for the conservation of the endangered breeds of animals that provide us with essential materials. I can, and do, teach through print, digital media, and the internet, and I plan to do more of that.

But there is no substitute for being in the same room with people and putting carefully selected fibers in their hands and considering together, on the spot, the questions that we come up with.

The embassies of all countries have much bigger issues than this on their lists of concerns and requests. Most of those have to do with averting or dealing with crises.

I hope that in this case the staff of the British Embassy in the United States, in particular, will have time to consider a situation that has the potential to strengthen international lines of communication and support peaceful, collaborative activities.

It might be a nice change of pace for them.

December 19, 2012

Q&A: Tibetan lambskin

From time to time, I've decided to do a few Q&A posts. Sometimes people write with questions that I answer, or take a stab at answering, or for which I can at least offer resources that will help the inquirer track down more information. I don't have time to do a lot of specific research other than what I'm already doing, but I do spend a lot of time reading appropriate source material and sometimes—as in the case of this recent inquiry—I happen across useful details, which may, combined with a bit of interpretation I can supply from having seen and touched and spun and made fabric with a lot of different fibers, come close to providing an answer.

Here's the first Q&A. I've edited the questions and amplified my responses to make them read more smoothly than our original e-mail volley did. However, the interchange retains some of the progression of information that came from our discovery process. The only photos are, unfortunately, accessed through links because I don't have time to track down the owners and request permission to include images.

For those of you interested in the topic of making doll wigs, the questions came from Jessica Hamilton, who is writing a tutorial called Doll Makers Guide to Wigging Fibers. It will consist of ten complete lessons on how to wig dolls of all types, including restoration and doll-alteration projects—sounds fascinating and useful! Jessica says the first lesson will be released free to all of her Doll Project newsletter subscribers, and she sends out free doll-related projects on the first Friday of every month. Her newsletter sign-up box is here.

Now let's deal with that question, which initially stumped Jessica, my co-author Carol Ekarius, and me, but ended up revealing interesting wool-related information.

_____

Q: I am a doll maker interested in doll wigging and hair fibers. I picked up your Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook. . . . What a wealth of information. I am finding all the information on loose fibers I could possibly need, but I am a bit stumped when it comes to popular lambskins. Many wig makers use "Tibetan lambskins" to create wigs. I realize this is the whole skin and is out of the normal realm of spinning, but I am hoping you can help. I having a difficult time finding out what exactly a Tibetan lambskin comes from.

In your book you explain that the name doesn't always really fit the fiber. Is the Tibetan really a type of sheep? Or is it just a name for the skin? What breed or breeds is it derived from? I realize the animal is killed for food and the skins are then harvested—do you know if there are ethical and/or humane concerns about skin procurement?

I read the first sections of your book and have read pieces and parts of the animal sections—I apologize if this information is already in the book, it's a big book! If this is the case, please let me know which section(s) I might look in!

Thanks so much!

A—phase 1: Pelts

Use of fibers for dollmaking and skins for pelts aren't topics I know a great deal about, but I may be able to shed some light for you.

Certain of the English longwools are often mentioned as resources for making doll hair (Lincolns, Cotswolds, Leicester Longwools), as is, of course, mohair, but mentions I've found for use of those fibers refer to their shorn form. These are especially supple, lustrous, long materials.

Co-author Carol Ekarius chimed into this conversation with some notes about what are traditionally called pelt sheep, which are raised, as more commonly understood fur animals are, for the skin-plus-fiber combination. Slaughtering is how those materials are acquired. The advantage to using sheepskins for doll wigs is that the hair doesn't need to be rooted in a base—it is already rooted. Some sheep bred for their pelts include Karakuls and Norwegian Pelssaus.

I'm a vegetarian. I prefer to have my fibers come without the skin—and for the animal who grew those fibers to continue growing more for the next year. I don't even like talking about how Persian lamb (from Karakul sheep) is obtained; the animal is slaughtered before or shortly after birth, because the fiber only has Persian lamb's characteristic texture and curl during a very brief period in the growth cycle. As the animal matures, the fiber quickly opens and loosens and becomes longer and wavier, instead of curly. I do read about Persian lamb because it reveals a great deal about wool growth, and the lamb pelt is amazing, beautiful stuff—which I can certainly do without as a material for crafting of any sort, although I think using it when it comes from an animal that didn't survive for other reasons (for example, died of natural causes, not just the obtaining of the pelt) is a means of honoring the brief life that produced it.

A—phase 2: Tibetan—geographic catch-all or an identifiable breed?

Next comes the question of what a Tibetan lambskin might be. Often such a broad geographical term refers not to a specific breed but to any sheep of any breeed from a given area, and that was both Carol's and my first instinct in guessing what you're dealing with.

Yet when I went to Mason's World Dictionary of Livestock Breeds, Types and Varieties by Valerie Porter and I. L. Mason, the latest edition (5th, 2002), I learned that there does appear to be a distinct Tibetan breed, generally raised for meat. Meat animals are most often killed young; the lambskins would be a byproduct and not the reason for the slaughter.

Here's what Mason's offers us in the way of breed information, with a geographic link I've added:

"Tibetan: (Qinghai-Tibet plateau, China, also N Nepal, also N Sikkim and Kameng, Arunachal Pradesh, India)/m.cw.(pa)/usu. black or brown head and legs; hd; st/vars: Sanjiang, Shangu, Tengchong, Yaluzangbu; strains: Ganjia, Ganqin/orig. of Qinghai Black Tibetan/Ch. Xizang, Aang, Zangxi/syn. (Nepal) Bhanglung, Bhote, Bhotia, Bhyanglung"

Well. Because the information is so condensed, deciphering a listing in Mason's can be like working a puzzle. There are a few items in there that I'm not entirely clear on, but I can put most of that data into plain English. This is my attempt to get as much information out of the listing as I quickly can:

There is a Tibetan breed, which is found in the locations noted. It's grown primarily for meat and produces a carpet-type wool. (The abbreviation (pa) means "pack" according to the book's key, but I don't have time to figure out what that means in this context. It doesn't currently make sense to me.) These sheep usually have black or brown heads and legs (that's clear enough). Both males and females have horns (if the males did and females did not, that would be indicated with symbols). They have short tails. Varieties or subbreeds derived from this breed include the Sanjiang, Shangu, Tengchong, and Yaluzangbu. Strains, or subpopulations, include the Ganjia, Ganqin. The Tibetan is the origin of the Qinghai Black Tibetan. The Chinese names for the Tibetan breed (Pinyin romanization) are Xizang, Aang, and Zangxi. Synonyms (names for the same breed(s) in one or more countries other than their place of origin or primary identification) are, for Nepal, Bhanglung, Bhote, Bhotia, and Bhyanglung.

(Note that Mason's introduction offers up a flexible definition of "breed" and doesn't define "variety" or "strain." There are practical reasons for this, although as a result we end up with useful but fuzzy information.)

A—phase 3: A follow-up response with some details about Tibetan sheep that fiber folk will understand

I've been doing research on other sheepy topics and just happened across some relevant information in an article. The source is Kalle Maijala, "Genetic Aspects of Domestication, Common Breeds and Their Origin," in The Genetics of Sheep, edited by Laurie Piper and Anatoly Ruvinsky (Oxfordshire, UK; New York, NY: CAB International, 1997, page 44). (Maijala is, by the way, one of the primary researchers into sheep genetics.)

"Tibetan is an autochthonous breed developed in the Qinghai-Tibet mountain plateau (now in China), at more than 3000 m of altitude. It is almost the only breed of Tibet and is also kept in northern Nepal and three regions of India. It is a carpet-wool sheep with a small tail. It is adapted to unfavourable environments and can deposit fat in the viscera around the stomach and kidneys and in the mesentery. The fleece weight of rams/ewes is 1.4/0.7 kg, staple length 9.5 cm and fibre diameter 20.6μ [microns]. There are 80% of true fibres, 5% of heterotype fibres, 15% hair and no kemp. The dressing % in males/females is 48.3/54.0. The average height of rams/ewes is 66/42 cm and weight 45/34 kg, and lambing rate 103% (Cheng, 1984)."

Okay! This is getting really interesting!

First, the Tibetan sheep is a breed on its own.

Autochthonous means, according to a dictionary, "formed or originating in the place where found." The use of the word is debatable in terms of long-term sheep history (and the debate probably can't be resolved) because almost all sheep originally came from somewhere else, but this does mean that these sheep are closely identified with their location and not obviously descended from other breeds in ways that we know about yet.

Because it is "almost the only breed of Tibet," then it has a defined identity in that region and we're not talking about whatever varied types of sheep happen to be in Tibet (even though there is variety within this breed, as we can tell from Mason's mention of varieties and strains).

Second, the description of the wool got my attention.

Carpet-wool: generally long, coarse, and often a mix of wool and hair. (The small tail is an interesting aside, because many of the sheep in the part of the world we're talking about have fat and/or long tails. Genetically this raises interesting, but not currently relevant, questions. Okay, avoiding a trip down that side trail. . . .)

They have small fleeces: ewes (of which there are many more than rams, no matter the husbandry goal of the flock) grow about 0.7kg (1.5 pounds) of wool a year. That's a tiny amount. The wool is a little under 4 inches long (9.5cm) and. . . .

Here's where I went on alert: "fibre diameter 20.6μ" (microns). That's in the range for Merinos. It's exceptionally fine. Classification of cashmere starts at 18 microns and goes finer. Average (not Merino) wool knitting yarns tend to be in the 25- to 32-micron range. Something very interesting is going on here.

That mix of fibers types (and their percentages) is also suggestive, but I'd need to see actual wool from the breed to talk a lot more about it.

Qs continue: This is fantastic information! In light of this, would you say the skins being purchased are still likely a regional mix of the carpet-wool breeds?

Do you know what age a sheep of this sort would be butchered for skin/meat? Is it the meat that dictates the slaughtering age or the fiber growth? I know if I can find these answers it should help further educate a doll maker's purchasing decisions when it comes to skins vs loose fibers. . . . [T]he already rooted fibers are easy to brush and style, but many creators snip the locks off the skin and use them for direct application, which defeats the purpose of having the skin. There is much more variety to be found in loose locks and fibers, as you well know.

A—phase 4: In sum, so far

I think at this point that the skins are likely coming from lambs of the Tibetan breed, and I say that only because the article in The Genetics of Sheep says that it is "almost the only breed of Tibet"—and because the description of the wool was unusual enough to get my attention. Thus the term "Tibetan" likely can be applied in both senses—type of sheep and geographic region of origin, and the wool likely does not come from a regional mix of carpet-wool breeds. My further investigations (phase 5, below) support me in this theory.

My original guess is that the slaughter occurs because of meat and the skin is a byproduct. Humane aspects of the slaughter would be determined by the husbandry preferences and cultural practices of the humans who keep the sheep. The age of slaughter would be determined by the meat aspect, rather than the fiber growth, and I would estimate four to eight months.

A—phase 5: What is this stuff like???

I looked up "Tibetan lambskin" in a search engine to see if I can give you a better answer to why Tibetan lambskin has become a mainstay of dollmakers' wigs.

The images I located showed me clearly why it's so appealing, and give some context to those of us not in the doll world. (I do note that some of the sites think that Tibetan lambskin is another name for mohair; it is not. Mohair, grown by angora goats, is quite different.)

Here's an image of a Waldorf-style doll, likely made of all-natural materials (as Waldorf toys tend to be). I hope it won't have moved by the time you look; this is a sale site for an individual item. Yet the text says the item is no longer available and the page remains, so perhaps it will stay put.

Here's a group of images of completely different styles of dolls, and includes detailed information on how the wigs are constructed.

Maijala's description of the average fiber diameter of the Tibetan breed as around 21 microns means this is unusually fine wool, especially for a breed with the length and texture seen in the fleeces—that's in the same range of micron counts as Merino, but for a very different type of fiber. That's why it makes good dolls' hair. (Merino would not, unless spun into yarn, which would give a totally different effect.)

It has an excellent texture and fineness; it has an intriguing appearance and feel (compared to the English longwools and mohair, it's not as shiny and has a "fluffier" look); it "falls" naturally; and it is likely pretty easy to work with.

Here's one supplier, with information on the status of the skin as a byproduct of meat.

Among collectors, I am guessing that some vegetarians (including most vegans) would not be comfortable with the use of the skins. And I'll bet that because of the texture and the ease of working with the material, they'd be sorely tempted. Making use of the skin is a way of deriving some good from the death of an animal that died for other reasons.

In short: Tibetan lambskin comes from a specific breed of sheep. It has unique and valuable qualities that make it especially well suited for making doll wigs. Where the ethical lines about its use get drawn is, of course, up to the individual.

December 11, 2012

UK visa requirements for people like me who might want to teach a fiber workshop, as far as I can understand them

I'm putting together this somewhat technical post in case any other potential fiber instructors or workshop sponsors might want to try to figure out the visa situation as it relates to U.S. residents (in particular) who might want to teach short workshops in the U.K. I'm summarizing my research and welcome any discussion, insights, ways other people have managed to leap the bureaucratic hurdles, and so on.

(Photo I took on one of the lovely walks I enjoyed around Stirling while the visa situation for UK Knit Camp was churning its way to conclusion.)

As I've mentioned, in the case of UK Knit Camp in 2010 even though there was preparatory correspondence about visa requirements and even though we overseas, non-EU instructors had supplied all necessary information in advance, once we arrived the paperwork was not in order. We could not teach initially, even as volunteers (notes about why below), and one instructor was turned back—i.e., had to spend the night in an approved location and fly back across the Atlantic the day after her arrival, and never did teach. One consequence of being found in violation of the visa requirements is not being able to enter the UK for any reason for ten years. (This did not affect the turned-back instructor, fortunately. She just had a very expensive round-trip, anxiety-wracked adventure.)

My source of information is the UK Border Agency website, which I must say is amazingly complicated.

The most promising category for traveling instructors in the fiber arts appears to be:

"Permitted paid engagement visitor"

"If you want to come to the UK as a visitor to do short-term, fee-paid activity you can apply for a visa as a permitted paid engagement visitor." The time covered is limited to a month. That's okay for almost all of us.

"The category of visitors undertaking permitted paid engagements is for a defined list of visitors who are invited to come to the UK because of their particular skills and expertise. They may apply to come here for up to 1 month without the need to be sponsored under the points-based sytem. The category is for visiting examiners or assessors; lecturers; overseas designated pilot examiners; qualified lawyers; and professional artists, entertainers and sportspersons."

In order to do this: "You must provide a formal invitation to undertake the pre-arranged engagement, and show that the engagement relates to your: expertise and/or qualifications; and full-time occupation in your home country."

The option requires sponsorship that may be possible for many of us to obtain, except that it isn't clear what level of formality is required in the sponsoring organization: "Visiting lecturers: You must be invited by a UK higher education institution or UK-based arts or research organisation to give a lecture or series of lectures in your field of expertise." or "Arts, entertainment or sports professionals: You must be invited by a UK-based arts or sports organisation or broadcaster to carry out an activity related to your profession in the arts, entertainment or sports. This may include fashion models coming to the UK to undertake a specific engagement, providing they do not intend to base themselves in the UK long-term." Would a fiber guild qualify as an "arts or research organisation"?

There are limitations to this option that apply to most of the other alternatives as well: "You must also be able to show that, during your visit, you do not intend to: take paid or unpaid employment, produce goods or provide services, including the selling of goods or services directly to members of the public other than as permitted for by the permitted paid engagement." I think this means that the "permitted engagement" list needs to include each workshop, if more than one will be taught. And I'm not sure what the paperwork and coordination for that would involve. I don't think sponsor licenses are required, but I may have missed that tidbit in the morass of detail.

How the mess was ultimately managed at UK Knit Camp

For a while, it looked like all the U.S. instructors were going to need to fly to Ireland and then re-enter the U.K., because all visa details have to be in place before entry. As it was, we took a useless round-trip drive to Glasgow, and then had to send our passports off for special treatment. High levels of government got involved in creating a way through the tangle of red tape, and while we didn't have to do a quick visit to an Irish airport, we did end up anxiously awaiting the outcome (as did the people registered for our classes: because the schedule had to be rearranged, I ended up teaching two classes simultaneously on the Friday of that week—fortunately, in the same room).

I was in a significantly better position than some of the other instructors because the teaching was only part of the agenda for my trip. Admittedly, I would not have made the trip in the first place if the teaching had not promised to pay the expenses and permit me to make enough to meet my bills at home. However, by the time I made the trip I was also going to do freelance research for the book (Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook) and for some magazine articles, which I did write and publish (although by themselves those articles would in no way have even begun to cover the trip's expenses). So I did have legitimate reasons for being in the U.K. beyond the teaching engagement, and those reasons did not require a visa or any additional paperwork.

(I had a wonderful time researching the Stirling tapestry project. Unfortunately, the magazine that published the piece had nowhere near enough space for what I wanted to write. Actually, what I did write, before I cut back to their word count.)

(The Sheep Day sponsored by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust took place at this lovely location, and there were amazing people in attendance.)

For the teaching portions of the activities, the UK Knit Camp instructors ended up with temporary residence permits as Tier 5 TW (Cre-Sport) Migrants; Cre-Sport means Creative/Sporting and the category is intended for entertainers (and presumably other creative types) and athletes. This classification requires a sponsor, who has to have a sponsor license for tier 5 (there are several tier types, and each requires that the sponsoring-and-employing organization pay a £500 licensing fee). Each sponsored individual must also be issued a Certificate of Sponsorship (a quite affordable £13).

A common theme within the visa requirements is that the person does "not intend to: take paid or unpaid employment, produce goods or provide services, including the selling of goods or services directly to members of the public." That "unpaid" provision meant that at UK Knit Camp we could not even work for free until the bureaucratic machinations had been completed.

Other categories

Here are the other options I have taken notes on—all are far more restrictive, expensive, or complicated than the "permitted paid engagement visitor."

Visitors:

- "General visitor" - "must . . . be able to show that, during your visit, you do not intend to: take paid or unpaid employment, produce goods or provide services, including the selling of goods or services directly to members of the public." This was what I was, as a freelance writer researching for future publications.

- "Business visitor" - "This includes academic visitors, visiting professors, overseas news media representatives and film crews on location." Sounds promising. But "you must be able to show that: you receive your salary from abroad (although it is acceptable for you to receive reasonable travel and subsistence expenses while you are in the UK)" and same as above (no paid or unpaid employment or services). I.e., no payment from U.K. sources.

(Admittedly, for tax purposes it is far better for U.S. instructors to be paid in U.S. funds on an U.S. bank. Otherwise we also have to figure out how to negotiate international tax filings, something I am failing at this year with regard to brief Canadian employment. The Canadian government will be benefiting to the extent of the money withheld, which I could legally reclaim if I filed another double set of tax returns, both provincial and federal—yet it would cost me more to complete this process than I would be refunded.)

(View from a hotel room in Glasgow.)

(Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow.)

Temporary workers:

"High value migrants" - these are on what is called a points-based system, and require a sponsor as one of the components of getting enough points to qualify. I think these are intended for people who plan to stay for a longer time and actually work a job that might otherwise be held by a U.K. resident (perfectly understandable that those would be protected).

- The writers, composers and artists category is closed and not taking any new applications.

- Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) includes "people who are recognised or have the potential to be recognised as leaders in the fields of science and the arts." Might be supportable in some environments, but there are a strictly limited number of these types of endorsements, and they can only be issued by the Royal Society, Arts Council England, British Academy, or Royal Academy of Engineering. And the application fee is £816.

- Tier 1 (Entrepreneur) requires even more money (investment of a huge amount of cash and guarantee of two new jobs for people already in the U.K.).

- Tier 1 (General) would have been promising, since "The Tier 1 (General) category allows highly skilled people to look for work or self-employment opportunities in the UK. Tier 1 (General) migrants can seek employment in the UK without a sponsor, and can take up self-employment and business opportunities here." EXCEPT "This category is now closed to applicants who are outside the UK, and to migrants who are already here in most other immigration categories."

"Temporary workers" of other types require sponsorship. This includes the previously used Tier 5 (Creative & Sporting), for which the sponsor must have the appropriate £500 license and the aforementioned individual Certificate of Sponsorship (£13).

In sum

This visa question poses interesting (if frustrating and befuddling) challenges. It would be helpful if those of us in the position of wanting to share information about fibers through workshops or presentations, and also to be able to meet our household expenses when we return home, can work together on what we learn about negotiating this labyrinth, climbing these cliffs, safely navigating these waters, or whatever it takes to get the job done. Especially, in my case and some others', because a huge part of what we do involves the use of British breed-specific wools and also carrying back to North America information that will increase awareness of, and presumably income from, British knitwear designers' and teachers' efforts.

If appropriate visa or permit conditions can't be puzzled out in a way that works efficiently and economically for the upcoming hypothetical trip, I'll have no problem simply enjoying the research and writing aspects (even though I do like to teach) and will plan upon my return to teach related workshops (somehow) by way of the internet, from my home base on this side of the Atlantic.

But it's so much more enjoyable and rewarding for everyone involved if I can put fibers directly into people's hands, and if we can talk in real-time about what we're discovering. I just don't know how it's possible.

(I have a lot of wonderful photos from my extensive walks around Stirling during the visa complications.)

December 9, 2012

British Isles 2013?

I apologize in advance if I'm not very responsive right now. The hard drive (six months old) on my computer (4+ years old) died completely on Friday, which explains the computer's increasingly balky behavior. The drive is under warranty, but at the moment the computer is best suited for use as a doorstop. Thus I have only intermittent and partial access to my working files—actually, I have the files. I just don't have the programs that I use to work with them. I'm sorry for any delays in getting back to folks. I'm working on it. Fortunately, this post was almost done and I transferred most of the photos to Dropbox as my mainstay machine wavered, then stumbled, and then quit. If a few of the photos here look odd, that's because for some reason those particular images inexplicably vanished during my emergency saving operations. And now to the main topic of this post. . . .

___

So there's plotting going on. It seems to be gathering momentum. Because there's close to a year to get ready, I might actually be in the British Isles next fall. I would be there to do more on-site research about sheep and wool, which is absolutely the best kind of research. (I do consider the research that I do on a daily basis, at home, with the help of books, interlibrary loan, e-mails, and the internet to be absolutely essential foundational work.)

Several friends with whom I've talked about my challenges in getting information of all types, as an independent researcher without any organizational sponsorship or funding, have been encouraging me to make a trip and offering both moral and some crucial logistical help.

Much Depends. However, the fantasy of this trip is coalescing around October 2013, in large part because of a number of events that will be taking place then, including Shetland Wool Week and the Campaign for Wool's Wool Week.

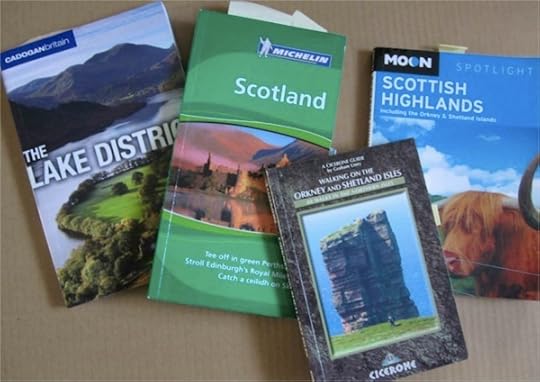

When I was in Scotland in 2010 for UK Knit Camp, I had hoped to take one side trip to do some research. I had to think of a single place that would have sheep that I wanted to have more firsthand knowledge about, that I could get to in the available time, and that would fit my budget. I settled on North Ronaldsay, in Orkney: Shetland was farther and more expensive than I could manage. I did a lot of what-iffing and planning. I got books. (I had maps.)

I discovered the land-and-sea methods by which I could afford to get to North Ronaldsay, and that the Bird Observatory offers good, inexpensive lodging, and vegetarian meals.

Then it turned out that I would need to be back in the States to help with photography for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook a few days after I finished teaching at UK Knit Camp. I could still get to North Ronaldsay, but I would need to fly. Flying wasn't in my budget.

Instead, with the help of June Hall and Sue Blacker, I went to Cumbria. I had a fantastic time. I also visited Glasgow for a day and a half as a way of making my trip to the airport easier (and more fun). (Kelvingrove Museum. Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Walking around, including from one accommodation to the other, since I couldn't get two nights at the same location. Bookstores: bought a map.)

Nonetheless, my interest in the contexts of the sheep, especially of Shetland, has been longstanding.

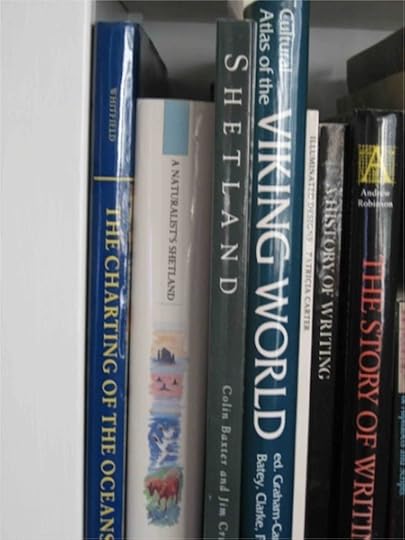

Close-up of a few of those books above:

I bought History of Scotland, Invaders of Scotland, Off the Beaten Track Scotland, Chronicles of the Vikings, and Penguin Historical Atlas of the Vikings at least a decade ago, and probably more like fifteen or twenty years ago, when I was researching something. The primary topic was probably sheep. The narrow item between the Scotland cluster and those two Viking volumes is the map of northern Scotland shown a couple of images ago. I suspect I got these resources when I was fact-checking items for Spin-Off. The map revision date is as of September 1992, and its printing date is 1993, which makes the "fact-checking for Spin-Off" and estimate of just under twenty years highly likely.

And. . . .

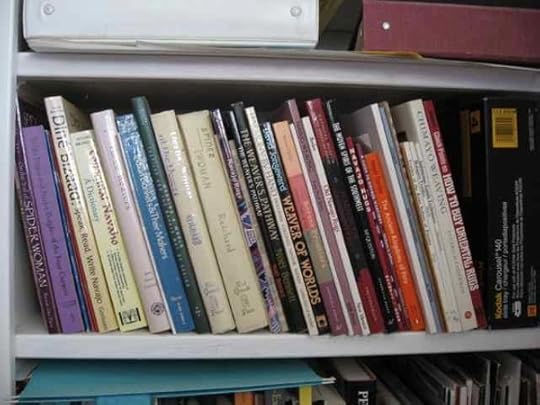

Another close-up:

Colin Baxter and Jim Crumley's Shetland: Land of the Ocean is, like the map of northern Scotland, dated 1992. I can tell from the label on the back, although the bookstore's name isn't included, that I bought it at the Tattered Cover in Denver. At the time, the main Tattered Cover store, where I went most often, was in the Cherry Creek neighborhood (the main store is now on Colfax). I don't remember where I came across J. Laughton Johnston's A Naturalist's Shetland, but I do remember that I caught sight of it in one or another independent bookstore when it was new (copyright 1999) and bought it without much internal debate, even though it was a hardcover and stretched my budget beyond its comfort level. It's a lovely book, although sheep are only mentioned on 9 of its 506 pages (and sheepdogs on just one).

I'm always interested in natural, cultural, and historical contexts. I've had some opportunities to explore those in relation to sheep (and generally) as I've traveled for other purposes. Because of time I've spent in the Southwest, I have always made sure that the vehicle I own has high enough clearance to manage two-track travel, away from pavement.

That's one of the shelves of books related to the Southwest, particularly textiles. I read Gladys Reichard's Spider Woman and Dezba, Woman of the Desert at least thirty-five years ago (they were written in the 1930s), about the time I was constructing a Navajo-style loom and weaving a rug that I gave my mother. (That was the same time that my cat had been hit by a car, and I spent a month tending him around the clock. He was a year and a half old. After the accident, he had only one intact leg-and-paw, one of the front ones, which earned him the additional nickname Thunderpaw. He lived to be fifteen; died in 1988; and I still miss him. Weaving the rug—which I did twice, since I pulled the weft out of the nearly finished first version because the edges were pulling in more than I wanted them to—and providing hourly care to that cat, whose most common name was Wow, are completely integrated in my memory.)

I do love books. But I love even more putting together the background information not only with the work of my hands, which I can do at home, but with the people, the landscapes, and the living animals that create and sustain both traditions and new visions.

So, while there are many places I want to go and people I want to meet and talk with, Shetland is very high on my list.

With the assistance of my "why not?" friends, we've gotten as far as picking a time to organize our ideas around (October) and securing a place to stay in the appropriate part of the world during Shetland Wool Week.

One item at a time: that's how The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook went from idea to completion.

As it stands, I will be traveling just to do research, and not to teach, although I've had people inquiring about whether I might be teaching in the UK in the foreseeable future. On the previous trip, I was fortunate that I was traveling both to teach and to do research, for the book and for some articles that I later published. For me, the trip had a clear purpose regardless of its outcome.

The ramifications of the visa situation that we overseas instructors encountered in getting permission to teach at UK Knit Camp were impressive. My explorations of the latest information on the UK Border Agency site (not the easiest resource for a non-UK resident to understand!) indicate that significant paperwork and fees, including investments for both sponsor licensing and individual visas, are required to clear all the necessary hurdles.

I don't want this potential upcoming trip marred by any potential problems. If there are other folks who understand this stuff better than I do and can help me negotiate the legalities, I'd consider teaching in person, which I love to do. If not, I'll be contemplating other ways to teach, likely computer-mediated. It's not the same as being together in person, and once UK Knit Camp actually happened I met many wonderful people whom I look forward to seeing again on the upcoming hypothetical trip. But teaching by internet doesn't require any visas.

In any case, I enjoy travel. I'm open to possibilities and suggestions. And some of this (or all, or more) just might happen!

* * *

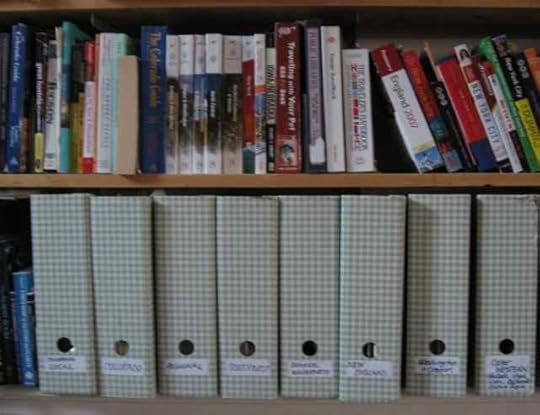

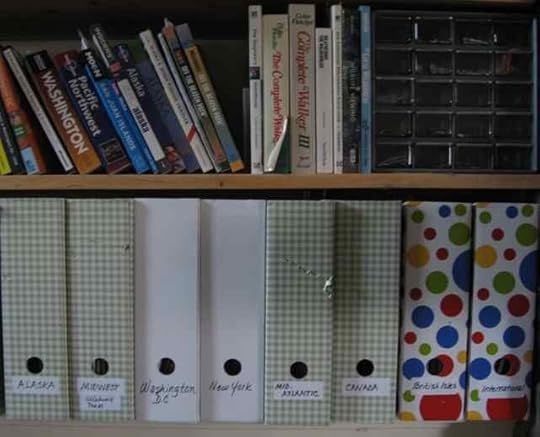

Have maps, will travel? Here's my personal map repository, part 1:

and part 2:

I couldn't get the whole shelf in one snapshot.

The brightly colored boxes on the righthand end include places I can't get to (theoretically) by walking, biking, or driving. The British Isles burst out of general International in conjunction with the 2010 trip. The only state in the US that I haven't been to is Hawai'i, although many years ago I was accepted to the university to study languages, and one of the things I have always wondered about is what my life would have been like if I'd gone there, instead of getting married. I've been in Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and British Columbia. I've been to Japan for a whole summer, and briefly, southern Spain (eight days, during most of which I had food poisoning; it was still a good trip). And the one trip to the UK for Knit Camp.

Due to previous adventures, many imaginary and that one real bit of 2010, I'm especially well supplied with maps of Scotland, although I have maps of other places in that part of the world. My aunt gave me her maps from her trips to the UK, doing genealogical research. I'm also willing to get new maps of other places.

Map of South East Scotland: one of my aunt's; copyright MCMLXXVIII (1978).

Pink-covered map of Barnard Castle & Richmond on the right: one of my aunt's, copyright 1982. Map of Penrith & Keswick: bought in Glasgow to help me remember where I'd been in Cumbria. Map of Ireland on the left: we got this almost a decade ago to see where our friend JG lives. The place is so small that it doesn't show up on any but the most detailed maps. Five years and a lot of saving later, one of us got to go to Ireland, including that tiny place, for two weeks.

* * *

Maps are magic. Maps can make dreams happen.

December 2, 2012

Sending more wool locks off to be photographed

It's been a busy six weeks. In addition to finishing work on the manuscript for a new project, I've selected, labeled, taken reference photos of, and packaged more than a hundred locks of wool.

Four breeds are missing.

One (Stansborough Grey) should be en route. I hope we're able to locate sources for the other three quickly enough to meet the deadline. The so-far-missing breeds are:

Brecknock Hill Cheviot—the Welsh breed, not the American Miniature Cheviot which was, through an odd fluke, once called "Brecknock Hill Cheviot";

Est à Laine Merino; and

the new type of Norwegian Spaelsau—the second most common breed in Norway. I do have samples of the older types of Spaelsau. Sometimes the rare breeds are easier to get fiber for than the more prevalent ones, because for the latter a bit of wool needs to be diverted from the processing stream and that's not always simple to accomplish.

(The colored stickers on the Brecknock Hill Cheviot card indicate that the breed is, according to The Sheep Trust, geographically vulnerable.)

I'm also researching two different topics for articles, and have some interesting freelance editing work about to arrive on my desk.

Thus perhaps the shortest post I've ever written!

November 30, 2012

June Hall: someone you'd like to know

My friend June Hall has been named Cumbria Woman of the Year, and a well-deserved honor it is. Not mentioned in the article at that link are a number of aspects of what June does, including her personal textile work, which warrants a spotlight of its own.

Completely under the article's radar are the great help June provided in gathering hard-to-find fiber samples for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, and the delightful time she facilitated for me following UK Knit Camp in 2010, when she took me under her wing and introduced me to people and places and sheep that I would not otherwise have encountered.

This is a photo I took through the windshield of June's car:

We visited a friend's farm. . . .

. . . with its flock of Herdwicks (and a few Gotlands and mohair goats). We also participated in a sheep day, for current and prospective shepherds, sponsored by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, and I got to watch and listen to Herdwick expert Jean Wilson talk about judging animals.

For someone like me who's interested in sheep and wool, I'll tell you there is nothing like a conversation with June, Sue Blacker, and Lawrence Alderson, all happening in June's living room. (It was June's cosy living room that demonstrated to me the delights of Herdwick carpet, and the trip we took to The Wool Clip that left me with a lasting appreciation for Herdwick blankets.) I'm still high on the experiences.

And I also now understand the special appeal of the Lake District . . .

and what fells are, and why hefting of sheep (a topic for another day) matters, all thanks to June.

And I'm just ONE of the people June has touched in this way.

If you went to look at the article, you probably noticed that June is working on a book about Lithuanian textiles. She's engaged in this project with Donna Druchunas, and I'm pleased to be a supporter of the work, and the book's editor.

But most of all, I am thrilled that June's quiet, persistent efforts are being recognized.

November 24, 2012

The Shepherd and The Shearer

I'm taking a break from my efforts to sort out the Norwegian spaelsaus (short-tailed sheep) to highlight a wonderful project that is right in line with the celebration of wool known as Wovember. It's The Shepherd and The Shearer, and if you want to be part of it here's the sign-up page, which I'm posting at the beginning since in the first twenty-four hours after the announcement at least half of the available two hundred spaces sold out.

Now I'll back up and give you part of the story, with links later to more details.

The gist:

1. Shepherd grows wool.

2. Shearer shears.

3. Special yarn is spun.

4. Two exceptional designers develop patterns for the sweater you just naturally wear all the time for work, play, and comfort.

5. A limited number of people, who have signed up in advance, get the results of all this next fall: special pattern booklet, enough yarn to knit one of the sweaters (they're thinking about an add-on for enough yarn to knit both), and, at the end,

6. Knitter knits: a classy, classic, year-in/year-out, wearable sweater (maybe two).

Oh, and there'll be a bag with that fantastic logo on it.

This is the sweater that inspired it all, on Susan Gibbs, one of the initiators of the project (and a shepherd):

The shearer is Emily Chamelin. She specializes in shearing sheep these days, and has to refer out to other shearers for alpacas, llamas, and goats because just doing sheep she has about four hundred shearing customers in a season. She works hard. She does fine work.

There aren't enough shearers working these days, and one of the side benefits of this project will be the establishment of a scholarship fund to get women to sheep-shearing school. Learning to shear doesn't involve huge expense, but it takes physical, psychological, and intellectual strength, as well as a love for animals, and folks who have that combination of attributes may not have the resources to get themselves over the hurdle of training, for one reason or other. In addition, women may not think of this as work that's open to them, and there's (obviously) no reason they shouldn't. This scholarship idea embodies focused encouragement to solve a few problems with just one of the extra goodies wrapped up in The Shepherd and The Shearer.

Moving on to the exceptional designers of the patterns:

Kate Davies, who has produced (among other things) Sheep Heid and Rams and Yowes and Deco and my particular favorite, Sheep Carousel, and a new book (available in about ten days)

Kirsten Kapur, whose Fractured Light mitts and hat are in a new Knitty, and check out Washington Square and, if you like mitts as I do (they're super for testing yarns), Twizz and Genmaicha.

If you'd like the back story, check out these links:

Susan's additional information

I'm looking forward to following the progress of this super idea! A whole year of delicious anticipation, and sweaters that will warm next winter in the knitting . . . and probably decades beyond in the wearing, because of the care with which the fibers have been grown and processed and the yarns have been constructed.

November 15, 2012

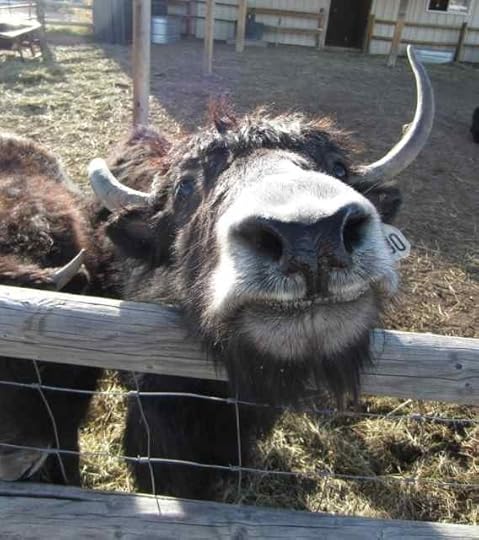

I love yaks (and their fiber)

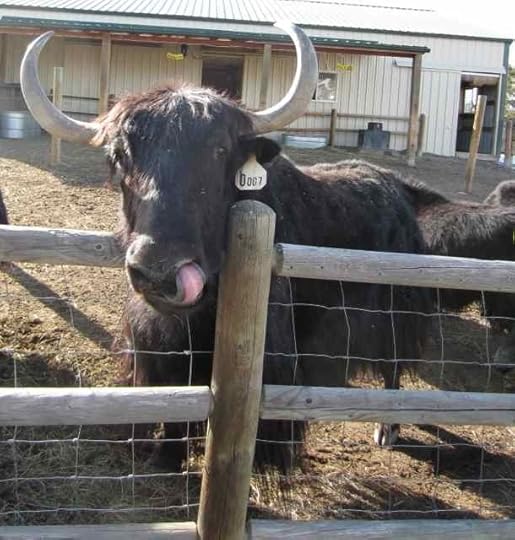

Yesterday I had the great good fortune of visiting Carl and Eileen Koop (and their yaks) at Bijou Basin Ranch. It was a 263.5-mile round trip and worth every bit of the journey. Here's part of why:

The yaks charmed me completely.

Backing up just a bit, here's a sign along the last bit of paved road (state highway, in this case) on my trip to the ranch.

And here's what that sign said:

West Bijou Creek. It's important in the story of this year on the Colorado plains to note that I didn't see any water in the creek. We've had a drought that's been affecting all sorts of livestock, including the fiber-producing types, like sheep and goats and yaks. I'll touch lightly on this again later.

Here's a view of the type of landscape in that part of the world.

And here's the type of wide county road I turned onto from the highway.

A number of miles later, I took the second right onto this narrower type of county road.

Over the years, there's obviously been enough water along that line running perpendicular to the road (likely a currently dry creek) to support the growth of those trees. It's good that they're well-enough established to withstand some dry times.

A few more miles, a driveway, and a turn into the yard brought me to this view.

Closer up, even before I said hello to Carl and Eileen, here they were:

I was at this point just under nine miles from pavement and twenty-nine miles from the nearest grocery store (which was a Safeway, but a rather limited one; I wanted, but couldn't get, unsweetened black tea, either cold or hot; they do normally stock it). The roads, however, were clear and well maintained. As long as there wasn't a storm of any sort making it impossible to see where the edges were (which there wasn't yesterday, but there was last Saturday, when I'd planned to make this trip), it was a smooth and easy drive.

There are nine yaks currently in residence. There were quite a few more, but a number needed to be sold to other ranchers because of the drought. The Koops see themselves as stewards of the land as well as of the animals, and even though they use a lot of supplemental feed they need to watch the condition of the pastures, which have diminished in capacity with the recent lack of water.

These yaks are the spirit behind Bijou Basin Ranch yarns. They provide the motivation for the Koops' business, and token amounts of fiber. The Koops want to do more to get yak fiber into our yarns than they could manage by growing it all themselves. So they work with other people who have yak herds, both in North America and in Asia, to make that happen in pretty magical ways.

I'll talk more about yarn (and spinning fiber) at the end of this post, but let's get back to the yaks I met.

This is Napoleon, the Big Guy.

He's especially fond of treats, and thinks he should have them all. (That's his YUM tongue-move.) The Koops make sure that their animals are well socialized, and put a lot of effort into establishing trust between animals and humans (and, consequently, vice versa).

These are Tibetan yaks. There are two types in this group, Imperials and what are called either gray-noses or Blacks. Napoleon is an Imperial yak. He's solidly black, including his nose.

So are this year's two babies (that's Napoleon's comparatively massive flank in the foreground).

The babies start out fuzzy, and as they mature their coats develop the mix of hair and down that will keep them warm. The down is also what makes luxurious yarns. (The hair is also a useful spinning fiber, but Tibetans know more about what to do with it, or with a mix of the two fibers, than North Americans do. We don't make many yurts here.)

Here's a baby face.

The yaks tolerate, and sometimes harass, the barn cat. Even the little guys chase the cat now and then. The cat goes with the flow.

Here's a this-year baby snuggled next to one of last year's calves.

Last year's complement consists of Knit and Purl, and aren't they fine-looking beings?

They're a little hard to tell apart. One is slightly larger than the other; I think it's Knit who is a little bigger than Purl. One of them was slightly lame when first born, possibly because of a lack of room to stretch out before they were born, but is fine now.

My photos of Ruby, Onyx, and Jade all ended up fairly backlit. But let's see what I can do for them and Doc. They're all grey-noses (Blacks).

Here's one of the ladies: I need a bit more help to tell the three of them apart, although they have distinctive appearances and personalities. I was just trying to learn all nine at once while engaged in fascinating conversation and taking pictures! (The first photo at the top of this post is another of the ladies, the one with a crooked right horn. The one with the crooked horn is not Ruby. Ruby is one of the two adult females with regularly angled horns. She is the least interested in being patted or given an ear-stratch, but I think she warmed up with time, and treats.)

And Doc is in front here, with Knit and Purl.

I tried to get a good photo of each of them, but I may need to go back and try again. That would be fun!

Recently I completed a pair of fingerless mitts using the laceweight, natural brown yak yarn that I got for the KDTV segment on yak fiber that I did last year (it's on YouTube). I made swatches for the show, and am now slowly (between other samples, research, and deadlines) using the leftover yarn to make teaching samples.

The pattern is Miriam Felton's Gable Mitts, from her book, Twist and Knit. I was a little concerned about how well the pattern would show up in such a dark yarn, but I'm pleased. I put the thumb gusset on the side of the hand (one of the pattern's options), and would probably use the palm-placement alternative next time, although I'm perfectly content with these. (I modified the thumb finish and cast-off slightly; the modification wasn't necessary, but I felt like it.)

The yarns. Ah, the yarns. That natural laceweight is, for me, the iconic yak-down yarn, but it's far from all there is to the inspiring and alluring array of Bijou Spun possibilities. When we went inside for more talk and a cup of tea, I almost disappeared into the yarns on the table. So much so that I forgot to take pictures. But let me tell you about some of what I saw there—and there are good photos at the link at the beginning of this paragraph.

There are both natural colors (brown and creamy-white) and dyed shades by Lorna's Laces. Weights range from ultrafine (a yak/silk 50/50 that Eileen is experimenting with but isn't satisfied with yet: it was absolutely delicious, and all I can do is trust that she has something even more exquisite in her mind) to light worsted (the yak/Cormo blend). There are also pure yak, natural and in dyed colors and in several weights; yak/bamboo; yak/Merino; yak with a tiny touch of nylon; and even more.

While any of these would make me happy at any time, my favorites are the yak/Cormo blend, the new yak/silk (a test run), and the sportweight pure yak (some in dyed colors). The yak/silk blend (Shangri-La) is a very slender yarn with enough twist to make it durable. It combines the shine and drape of silk with the warmth and body of yak. Note to the knitter who doesn't mind fine needles and has been looking for something extraordinary: check it out. In the right light, that gray is really silver. The other colors, not as intense as Eileen requested, are knock-me-down beautiful anyway.

Bijou Basin also has, for spinners, "clouds" of down, which are a far cry from the fiber I encountered in the course of a freelance spinning-and-knitting job I did about thirty years ago. An Ivy League professor brought back mixed hair and down from "the Himalaya" (his term: I was never sure exactly where). He wanted it made into yarn and then into a sweater. I tried to talk him into shifting his goal to a welcoming rug for his office, but he would not be convinced, even by my most compelling arguments about the potential disadvantages of a hairy garment. (I was, and still am, convinced that the people who sold him the fiber could not imagine that anyone in North America could or would be spinning the stuff, and so sold him what they didn't want. Yes, they do often use the fibers mixed. But the condition of these several pounds of fiber was beyond the line of simply alternative preferences.) I did make him a sweater, as he firmly requested (he was paying the bill! and I needed groceries), although I purchased color-matched Lopi yarn for the ribbings (cuffs, neck finish, and lower edge), in order to give the sweater a chance of being wearable. I still wonder if he ever put it on for more than a few minutes. I never met the man, and I doubt that I will ever know what became of the sweater.

We fiber folk—yarnies and spinners alike—have come a long way from those days, in large part because of Bijou Basin Ranch. Their down ranges from 15 to 18 microns; in fineness, that's excellent cashmere territory.

What a wonderful day. Thanks to Eileen and Carl! And to their irresistible yaks.

___

Why did I happen to take a trip to Bijou Basin Ranch at this time? I'm gathering materials for the second Explore 4 Retreat, to be held in Friday Harbor, Washington, March 10–15, 2013. Each day will focus on a different fiber. One of last year's participants requested that 2013 include yak, so yaks we shall have! If the retreat were closer to Bijou Basin Ranch, we'd be taking a field trip. As it is, I picked up information—and fiber!—to share with the group. (The event is full, with a short waiting list.)

Napoleon says I need to end with another photo of him.

He's very handsome. Also basically humble, if just a touch at-the-front-of-the-line-please.

October 31, 2012

The 30th Spin-Off Autumn Retreat

Last week I took a quick trip to Granlibakken, in Tahoe City, California, to participate in a few days of the 30th Spin-Off Autumn Retreat, best known as SOAR. This post will consist mostly of a series of not-too-great but definitely on-the-scene photos, with captions.

SOAR began because Linda Ligon, who founded Interweave Press, thought that spinners needed their own gathering, not just to be the stepchildren at weavers' conferences.

At the time, Anne Bliss was the editor of Spin-Off magazine, which was transitioning from an annual publication supplemented by quarterly newsletters to the quarterly magazine it still is. (Spin-Off editors over its thirty-five years—the publication is five years older than SOAR—have been: Anne Bliss, Lee Raven, me, and Amy Clarke Moore.) I don't have photos of Anne or Lee handy.

Linda asked Dale Pettigrew to put the first event together, and Dale went on to become the SOAR coordinator as the gathering grew and moved around the country.

I came in at the fifth SOAR, which was bigger than the previous ones (because it was the fifth) and had the first real marketplace and added pre-retreat workshops as well. That was 1987. It worked so well that the market and additional offerings continued.

A lot of the event's spirit and practices were shaped by Dale. In 2008, she was in a bike accident. No one's exactly sure what happened, because there were no witnesses (she was found by a passerby on the ground next to her bike, on a bike trail), but she spent a month in a coma, including several weeks on a ventilator. She has had to slowly re-learn how to talk and walk. Initially, she thought she would never spin or weave or knit again.

But the brain and the spirit are both amazing, resilient things.

When the idea arose to get Dale to this big-anniversary SOAR, she had been spinning again for a while and had begun to weave once more, using a rigid heddle loom. Interweave and several individuals pitched in to get Dale to Granlibakken, with me as her traveling buddy. One of the biggest challenges turned out to be transporting a spinning wheel for her. She has two wheels, one of which is a Rick Reeves that needed to stay home. The one we needed to get to and from California was the first Louet S-90, which had been introduced at SOAR in Silver Bay, New York, in 1997 and signed by a bunch of folks there.

First we had to find a container large enough. We tried suitcases, and ended up finding U-Haul flat wardrobe boxes. Then we had to make that box fit within the allowable luggage dimensions for Southwest Airlines and reinforce it so it would be sturdy enough to fully protect the wheel. We ended up using two of the wardrobe boxes, one inside the other, cut down so that there was room enough to pad the wheel on the inside and yet had outside measurements within the airline's requirements. We ended up with an inch to spare on each critical constraint, and the wheel traveled in both directions unscathed.

It was snowy at Granlibakken (Dale and snow seem to go together), so we needed to rent a 4WD vehicle in Reno rather than the compact we'd reserved.

But there was so much warmth at SOAR! Here Dale and Jodie, a much-loved long-time SOAR participants, look through, and identify people in, one of the many SOAR albums. (I snapped the photos of Linda and Dale at the start of this post from one of these albums. They are from a very early year, but not the first.) Pat Wagner Thompson was the SOAR photographer for many years. We missed her!

The SOAR community extends over years and also across the globe. Richard Ashford is often there, and his wife Elizabeth got to come this year, too. Here they are with Jodie. (The handspun garments everywhere are enduring "friends" as well.)

I didn't get photos of so many people: Gord Lendrum and his wife, Linda; Selma Miriam; Charlene and Charlene; Stephenie; Jeannine; Kris. . . . the list goes on. We invoked the presence of many others by remembering them, and we also quietly welcomed new community members who were present for the first time.

A few long-timers attended in unusual forms. Here's Dale (center) with instructor Maggie Casey and wheel-maven Cindy Lair, whom sometimes is able to be at SOAR three-dimensionally. (In the background that's Maggie Reinholtz, who started out as a member of the events staff a while ago but I hear got to participate in a workshop as well this time!)

SOAR is more a community than a conference, and a lot of the reason that's the case is Dale Pettigrew. She set and maintained a tone that still imbues the event.

On Thursday night, I gave a talk on rare-breed wools. . . .

. . . after which we got Dale up there to talk. This is Amy Clarke Moore, Spin-Off editor; Dale, wearing a gorgeous sweater made and given to her by frequent SOAR participant Paula Shull, who unfortunately wasn't there; and me.

The gallery and the market were wonderful. I have about forty snapshots from the gallery, one of which I want to share here. This is Lundie Robb's "shepherdess and friend," made from rare wools and absolutely exquisite. Talk about capturing the joy of the craft, its history, present, and future:

What joy there is at SOAR throughout the gallery and the market and the dining room and in the workshops and walking through the halls!

It all started with a seed of an idea, grown for thirty years into a sturdy connection around the globe and, now, across generations.

Thanks to those who began this group adventure: Linda and Anne and Lee and, most of all, Dale.

And to everyone else who has participated, or thought about participating, or will be joining the community in the future. It might be snowing outside, but it's plenty warm when we gather together to spin and learn.

_____

Long before I came on the scene, Dale found a poem by Pamela Kelly that has served as a touchstone for SOAR since its beginning:

AS I SPIN . . .

As I spin,

I watch the fibers

Twist

Assuming a stronger character.

I reflect on the twists

I have endured today. . . .

As I spin,

I think of other

people—

a parade of a thousand

years.

Meditating

hour after hour

at the spinning.

I, like Gandhi,

fold up my wheel

and carry it with me

to the meeting place.

—Pamela Kelly

_____

Footnotes:

Thanks to Kris Paige for wielding my camera at critical moments.

Interweave, the company that sponsors SOAR, has been sold twice in fairly recent years. Seven years ago it was sold to Aspire Media. About three months ago, Aspire (including Interweave) was acquired by F&W Media. It's not clear what effect this may have on future SOARs. There have been some layoffs, predominantly in departments other than editorial. The events staff will be changing. The spirit of SOAR will continue, although it may need special care and nurturing to weather the newest transitions.