Deborah Robson's Blog, page 7

August 10, 2013

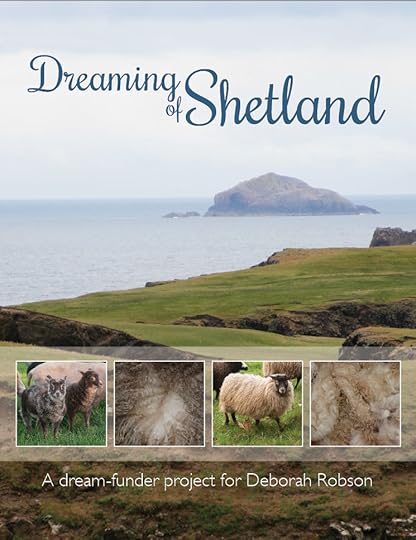

Dreaming of Shetland launches!

In February, friends came up with an amazing and unexpected idea to help me do the next phase of research into sheep and wool, which involves a study of Shetland sheep and their fleeces. Shetlands are really complex, even controversial, and consideration of their development and current situation encompasses many questions relating to fibers, regardless of type or breed. They're a microcosm of the wool world—physically, historically, and culturally. I wrote about "Why Shetlands?" in an earlier blog post, and that piece was initially constructed for and appears in the Dreaming of Shetland e-book that is coming into being through these folks' amazing and unexpected idea.

Their idea: to ask a selection of talented people each to contribute a pattern, an essay, or some other item to what would be combined into an e-book anthology, the sales of which would be used to fund my Shetland inquiries: essentially, a community fundraiser, operated informally (albeit rigorously) and in ongoing fashion. Here's the associated website.

The gist: They asked me to meet with them before lunch one day at an event we were mutually participating in. We sat down in the empty dining room. They told me that they had "an idea" and that all I would need to do was "say yes" and "have a PayPal account." Well, I do have a business PayPal account, which I use mostly to buy fiber and books (about fiber, surprised?).

So they gave me the outline: people within the knitting community who might have an interest in seeing what I would come up with in the way of research would be asked to contribute a pattern each to a collection. The plan was to have the whole project happen quickly, so that patterns that would be included would likely already exist—for example, a neat design that was still in the files because it had never found a public home.* The instigators (more on them both below and in a future post) would assemble, design, and set up an e-book collection through Ravelry (to keep this as simple as such an outrageously ambitious endeavor could be). All proceeds would go to my research.

* It only sort of worked that way. A lot of people got inspired to create original designs.

I was, and am, gobsmacked. I prefer to be stubbornly self-reliant and can be more independent than most cats. Yet I am also obstinate about my research, which was being implemented at about 1/1000 the speed that I envisioned, for lack of resources.

I looked across the table at their inspired faces. I thought about the sheep. I thought about the wool. I thought about knitters and weavers and spinners of the future. I thought about all of us now, and how much we appreciate knowledge that deepens our craft and our appreciation for life. I thought about how I am relatively reserved (yes, I can talk fine in public—when I'm talking about fibers) and that this would put me in a bit of a new spotlight—and I decided that the spotlight would be on the sheep, and I could just be a lens. And I thought that at this point in my life, I'm in a position to ask questions and know how to dig for information, if not answers, and to put together what I discover in ways that others may find interesting and useful. I thought about the sheep again—all the sheep, in addition to the Shetlands—and all of the lovely, dramatically versatile and dissimilar wools they grow, wools that we need to know better. And I envisioned that at the end of it all, lots more people would be connected to, and know the joy of, the sheep and their fleeces. And that it could be fun for everyone involved. (And a lot of work. I had no illusions about that. They didn't, either, although like all good things it has become more than anyone expected.)

I slowly nodded yes, making myself say the word out loud as well. I knew that, because of the people who were already involved and those who might be, this would be a big deal.

Yes.

For the most part, I was asked to pretty much stay out of it—to, if I had a spare moment, go research sheep and wool. So I was asked to write the "Why Shetlands?" piece and to review the sheep photos that would be on the cover (to determine whether they were of the Shetland breed, or simply sheep of other breeds in Shetland). While I've seen the photography for the projects (both the photos and the designs make me want to pick up my needles, and in one case I already have), the book is as new to me as it will be to those who choose to buy it.

The scope: The project got quite a bit bigger and more complicated than the initial intention (doesn't everything?). As matters proceeded, the organizers needed to put a cut-off date on participation in order to actually make it happen within anyone's lifetime. They also decided to release the book in sections, in order to make the logistics (and the file sizes) manageable, although signing up for it once will, over the next several months, yield the whole thirty patterns and associated articles and photographs.

In the interval between the idea's origin in February and the initial release a few days ago, two things became apparent to me. One was that without some practical help, it would take years, or decades, to accomplish anything toward this research, and the second was that the moral and psychological support of the idea alone has already been hugely beneficial.

A quick note: Even though the release of the e-book has been "soft," without a lot of fanfare and the "announcement" mostly by word-of-mouth so far, the initial proceeds have already enabled me to obtain resources that have previously been very difficult or impossible for me to access.

Whose idea was this?

The idea came from Donna Druchunas, and Anne Berk immediately stepped in to collaborate, enlisting her husband, Bill Berk, to do the photography. Donna's husband Dominic Cotignola provided invaluable, and mostly unheralded, technical help.

Sarah Jaworowicz supplied creative energy, organizational prowess, and graphic design skills.

Susan Santos coordinated the tech editing and kept everyone centered and optimistic.

But listing those individual responsibilities obscures the closely integrated teamwork that even from a distance I was fully aware of, as they nurtured a spark into a whole series of warm campfires to offer to the fiber world.

It says "for Deborah Robson," but I'm just the conduit here. Although yes, I have a dream that this research and our mutually growing efforts and knowledge will have a long-lasting and positive effect on our fiber activities and on communities' and individuals' and several landscapes' health.

Whose work is featured?

The designers and researchers and creative souls who have graciously and enthusiastically come forward to make Dreaming of Shetland a reality include:

Deb Accuardi

Gladys Amedro (with some help from her friends)

Janine Bajus

Anne Berk

Amanda Berka

Cat Bordhi

JC Briar

Beth Brown-Reinsel

Ann Budd

Ava T. Coleman

Linda Cortright

Susan Crawford

Jeane deCoster

Donna Druchunas

Priscilla GIbson-Roberts

Ann Glassley

Franklin Habit

June Hall

Sivia Harding

Lynn (ColorJoy) Hershberger

Shelia January

Jennifer Leigh

Lynette Meek

Cheryl Oberle

Cheryl Potter

David Roth (elusive online) got involved, too, with his camera

Betty Salpekar

Susan Santos

Kristi Schueler

Myrna Stahman

Jeny Staiman

Meg Swansen

Stephannie Tallent

Nancy Powell Thompson (internetarily semi-invisible, and a wonderful designer)

Gladys We

Jill Wolcott

Take a look at the kinds of work they've packed into the e-book here.

I'm looking forward to seeing and reading it myself! One of the reasons it took me a few days to put this post together was that when I got the preview section last week, I read Donna's dedication and had to compose myself. I always see the shortfalls of what I do: I want to do more than any day permits, and I want to raise all of our boats together. Donna's words let me see that even when my reach exceeds my grasp, I may be getting a handle on some things in a way that's helpful.

So if you are inclined (with all those incredibly talented people involved, I don't know how anyone could resist, even if this were "just" a regular book), there's information on the website (of course they put together a website {wry grin}).

Meanwhile, I need to get back to the quest. As soon as my eyes quit misting up and I can see clearly again.

Thanks, all. I'll bring back sheepy and woolly information and share it.

Photos © Deborah Robson

Dreaming of Shetland cover design by Sarah Jaworowicz

July 29, 2013

One way to wash fleeces, part 3, quick overview and then drying

The previous two posts covered, in some detail, my preferred fleece-washing process, with part 1 covering preparations and part 2 the soaking cycles. In this post I'll summarize the accomplishments of that sequence of soaking baths in one instance of a filthy fleece, and then I'll talk about getting the wool dry.

Remember this fleece?

This is the fleece I showed in the first wooly image of part 1, about how to figure out how much fiber will fit in a batch. Dirty, wasn't it?

The other half of that fleece was even grubbier.

Here's how that second half progressed through the baths.

I didn't record precisely where I was in the process when I snapped the photos, so my dividing points between plain-water and cleansing baths may not be exact, but I'm guessing that because of the extreme grunge I gave it three initial soaks.

Then I added the Power Scour for three washing soaks, including a flip. This was, indeed, dirty wool.

This has been flipped from the first wash.

And two final rinsing soaks, but just one photo.

At this point, I assigned responsibility for the remaining discoloration to mineral staining from the dirt. That sort of thing isn't likely to be gotten rid of without serious chemical intervention, which I'm not willing to do, and I know that the finished yarn will look fine (believe it or not—sample pictures to follow later in this post).

Drying

We'll return now to the fleece used for most of the washing photos. It's been through its final rinse and is ready to start the drying portion of the activity.

This next part goes fast.

It's time for the lingerie bags. I put each wool tray crosswise on its container tray to start draining. Then I tip one wool tray so a corner is inside a lingerie bag and let the wool slide from the rigid tool to the flexible one, offering encouragement (often just by shaking the washing tray) as needed. I zip the bag shut.

If I'm going to do another washing sequence immediately, I'll save the final rinse water and use it for the first soak of the next batch. That bag up there is probably sitting directly in the water of the container tray. It will drain out when I lift the bag. I don't squeeze the bags or do anything else to them.

I'll often use the smallest solid tray to collect the wool-filled lingerie bags, and then to carry them downstairs to the washing machine, which I use as a centrifuge to get out a good portion of the water.

I have a top-loading washing machine with a spin-only cycle. I sure don't want to have water running directly onto my wool at this point!

I put the bags in and distribute their weight relatively evenly around the tub, make triply certain that I'm selecting "spin-only" from the dial, and then let the machine do its work.

(If you have very sharp eyes, you may be wondering if this has suddenly turned into a Jacob fleece. It has.)

In medieval times, when there were no washing machines, there were spin-only cycles. They were found out of doors next to a wall or a fence with a shallow hole at about waist height. A bag or basket of wool would be tied to the middle of a long stick. One end of the stick would be stuck into the hole, and the power source (a human) would hold the other end of the stick and move it quickly in a big circle, causing the bag to swing around the stick and the water to fly outward. This was called wuzzing. (I wonder if, when this was done in the summer, kids ran through the "sprinkler"? Or if teenagers were sent outside to expend some of their excess energy by providing the wuzzing power? I wonder if there were ever wuzzing contests?)

If you don't have an appropriate washing machine and don't feel like putting together a wuzzing arrangement, you could seek out a big salad spinner at the thrift shops while you're looking for your washing containers, or you could roll your wool in an old terrycloth towel like a jellyroll and then squeeze some of the water out into the towel. If you truly have no resources for getting water out, you can just lay out the wet wool and it will dry, although it will take longer.

In any case, the next thing you want to find is a place where air can circulate around the wool. Ideally it will be out of direct sunlight and not near a fire. The free air circulation is the most important part of drying; heat and sun exposure can damage the wool (especially now that you have removed its protective coatings). The damage might be slow, but why risk it?

One bag- or tray-full covers about half of one of my stackable sweater dryers, so here are the first two batches in one layer:

(Note the card identifying which fleece this is. I always think I'll remember, but I nearly always remember that's a mistaken idea.) Here's the third of the three bags' worth on a second dryer, stacked over the first:

The wool in the big mesh bag to the left is clean—probably the earlier batch from the same fleece, waiting for the rest of it to come along. At the bottom right, in plastic, is a raw fleece needing to be taken upstairs and doused in water.

At a moderately busy time, there are four drying racks stacked on the guest bed (potential visitor be warned), one propped on a towel over on the left, and several fleeces in large mesh bags almost ready for labeled-clean storage and several more in plastic, as I received them, needing the whole treatment. Yes, that's a fan on the bed. It's mostly for household air circulation in the summer, but it can also speed wool-drying when necessary. I currently have eight stackable drying racks of the same type, and sometimes I use them all. Lack of drying racks can be the bottleneck in wool washing. (Spreading the wool out on towels works, but with less air circulation it again takes longer to dry.)

During the drying time, I sometimes flip over the batches of wool. It's not necessary, but can speed the process just a bit. I think mostly I do it because I like to say hello to the wool again and admire it from another angle.

This is what happens when I have to leave to teach and some of the wool isn't quite dry.

Air circulation. The fact that the hotel's air-conditioning unit was near the window was completely irrelevant. I turned the fan on low/no-cooling and the wool, which I rotated when I thought to do so, was fine by morning.

Sorting the wool

Some of you will have noticed that I don't sort the wool for quality before I wash it. If I were dealing with one or two fleeces at a time for my own use, most likely I would, putting the coarser or dirtier bits in one pile and the finer or cleaner in another. However, most of the wool that I wash will be distributed to participants in my workshops—and I have, at any given time, a dozen or two fleeces that need to be washed and stored and then packaged and then. . . .

The storage and fussy labeling issues alone would be insurmountable if I sorted before I washed, and when I do make up packets for classes I try to grab different types of fleece for each bag, so the people in the workshops get a sense of the range of possibilities from a breed. I could do that more methodically if I sorted, but I'd also go nuts.

If I do decide to use a portion of a fleece for myself, I find it simple enough to spread the clean wool on a sheet and, by touch, pull out sections that feel compatible with each other.

Your needs and procedures will need to be tailored to fit each other, as mine are.

The big points: (1) Don't worry. (2) Don't agitate. (3) Don't let the water cool off too much between baths.

So you find it hard to believe me when I say some really dirty wool can clean up quite nicely?

Note the different textures of the wools in the next four photos. They are all white (to make it easy to see their basic form) and they are of several different types. None of these was an especially clean fleece. Certainly none was coated (I get some coated fleeces, but mostly not). The Down wool (the second photo) has rather a lot of vegetable matter in it (typical!), which will mostly drop out as it's picked in preparation for spinning.

Will those formerly very dirty wools truly make nice yarns?

In my opinion, yes.

This is Rouge de l'Ouest, a meat breed, which arrived with characteristically dirt-tinged tips, and a fair amount of grunge farther down the staples. It washed up pretty well, leaving slight discoloration at the tips. The yarn looks just fine.

I mentioned that the washing technique I use works for all types of wools, including those inclined to felt or to end up sticky (because they carry a lot of lanolin) or to otherwise be difficult. Here's some Romeldale:

Every one of the fibers I've shown here—and all the fibers I cleaned for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, which was everything that came to me in raw form—was washed with this method.

As I said, the results are delicious to work with.

In sum

Spinning from wool you have carefully washed and prepared by hand is like eating fresh-picked, tree-ripened apricots, still warm from the sun.

Haven't tried it yet? Do. You don't have to wash all the wool you spin. I don't. And sometimes in the winter I buy hydroponic tomatoes, too.

July 28, 2013

One way to wash fleeces, part 2, the wet work

Part 1 of this set of three posts covered my basic approach to washing, the equipment I use, and figuring out how much wool to include in a batch. Now we'll get the wool wet and start getting it clean.

Basic water-filling or changing technique, demonstrated with the first (plain-water) soak

The procedure here will be followed for all of the changings of the water, although you'll see some variations on the theme as the photos progress (mostly because all the changes after this involve already-wet wool).

For this first run, I'm using warm, plain water. With a filthy fleece, I might start with one soak in COLD water and leave it for as long as overnight. (If the water isn't warm, the redepositing problem mentioned in post 1 doesn't occur.) I might even do two cold-water soaks for something full of mud that I want to salvage. However, for the most part we need the bathtub for family use at night and in the early morning, so if I do a cold-water soak it's most often just from when I get up to after I've had breakfast and am ready to get serious about washing some wool.

I need to get water into the bottom, solid trays without running it onto the wool (which counts as "agitation" and can lead to felting). By placing the wool-filled trays at right angles to each other, I can balance them all on the solid tray farthest from the faucet. I'm using two of the large trays and one small one here. All of this wool is still dry.

I run straight hot water into the tray nearest the faucet.

I put the matching wool-filled (perforated) tray into the water-filled base and just let it begin to sink on its own.

I slide that small tray to the middle position, lifting the available empty bigger tray over it, and fill that one in turn.

After settling the second wool-containing tray into that newly filled receptacle, I lift the remaining empty container tray to the faucet end, putting its still-dry wool tray crosswise on the first tray, which has now moved to the far end of the tub.

I always slide full trays away from the faucet and lift-to-move the empty (or recently dumped) trays.

Now all three trays have water in them, along with wool that has begun to get wet.

If you are nervous, you can leave the wool to sink into the water on its own. It will.

But I like to speed things along a bit and also to get gently involved at this point. So I put on my gloves and softly press the fiber so it's all immersed in the water.

Here are all three trays of quite a clean fleece taking their first soak in warm water.

I walk away and leave them for 20 minutes.

When I come back, I check to see how the dirt is dissolving by gently pressing down again.

Moving trays with wet wool

It's time for the second plain-water soaking. If the wool is quite clean at this point (the sample above is pretty clean), I might move directly to a washing bath, but usually I think that the more dirt I can remove with just water, the better.

So we're ready to prepare for the second soak. The upper trays are quite a bit heavier now, because the wool is wet. As I move things around, I have added the goals of not sloshing (much) water on the floor, and of draining out as much of the dirty water as possible before putting the wool trays into fresh water. The extra trays that came with the cat-box sets are about to come into play to provide more working space.

First I take one of the perforated trays and put it crosswise on its base. This allows a lot of the extra water to drain out. (If I'm using colanders, there's space at the end of the tub farthest from the faucet to just set them there to drain.)

Then I use one of the extra trays, set right next to the tub, to get the somewhat-drained first wool tray out of the way.

This is the point at which water can start making inroads on the bathroom, so I'm careful about the placement of the extra tray and the movements I use in transferring the wet-wool tray.

I continue to use that far-end tray to support the two other wool trays.

I dump out the dirty water by simply tipping each solid tray up on its side. (One thing I'd like to be able to improve about my system is being able to put the waste water on the yard and garden. That's not currently feasible.)

Then I refill the trays, sliding each over away from the tap as it is filled.

And I set the wool back inside as each container tray is ready. (Interesting color shift between drained and soaking wool, isn't there?)

Ending up with the one original tray with dirty water in it, ready to be dumped so it can have its portion of wool (resting in the tray outside the tub) back again. The water ready to be dumped here is from the end of a second rinse, which is why it's not as dark as in the photo farther up in this section.

If you have really dirty wool, the tub after a first, or even second, rinse can look like the bottom of a riverbed. Here's a different fleece, and far from the worst I've ever seen (but take a look at how white that wool is already, from what you can see at the far right edge of the photo; differences like this happen dramatically in the first soak or two).

Reminder:

Adding the cleaning agent: washing

I do the plain-water preliminary soak once, twice, or three times. The condition of the wool, your patience, and sometimes just the available time will determine how many initial soaks to use. I don't expect fully clean water at any stage, and that's not what I'm going for. However, as the soaking and water-changing continues, the water will become clearer.

When it's time to add the cleaning agent, the technique differs very slightly. You could add it to each tray individually and do just as you did before, but I find it's more efficient to "treat" all trays with the scouring agent at the same time.

I set the trays crosswise to drain a bit, and empty the old water.

Because I need access to all three bottom trays at the same time, I stack the wool trays in the extra working space outside the tub. They've already drained partially, so I don't need to arrange them in crosswise fashion. (Yes, I do have to empty extra water out of the holding tray after they're all back in the tub.)

In filling the solid trays, I continue to slide the full ones along the bottom of the tub. They're heavy, and I don't want to slosh and waste water.

When all three have clean water, I add a squirt of cleansing aid to each. It's in a pump dispenser that I balance on the edge of the tub while squirting. (I have the giant size. I use Unicorn Power Scour, which is specially formulated for use on grease wool. A little goes a very long way.) When I used dishwashing detergent, I might need a quarter-cup or so to each of the larger trays. With specialized wool-wash, I use a tablespoon or two (a half-squirt or so).

I gently swirl the water in the tray to distribute the cleanser. It's the same process if you use something like dishwashing detergent, but in that case you keep the swirling especially low-key because you don't want to raise any more suds than you have to (they're hard to rinse out).

A note on cleaning agents: Even though I'm wearing gloves, I won't use anything I don't want to keep my hands in. I look for low personal and environmental impact.

I re-settle the wool trays and press down to be sure the solution reaches all parts of the fiber.

20-minute timer. . . .

When I come back this time I examine the fiber with an aim to loosening up any clumps of dirt that remain. I wait until after the first washing soak so the cleanser has time to do some of its magic. What I want to do at this point is make sure I'm loosening up any clumps so the solution can get inside them.

I do not want to agitate or rub the fiber. I do want to open up stuck spots. I'll give you a series of photos of what that can look like.

I find a spot where, for example, the tips of a lock are holding some dirt. (Note that I'm not doing anything about that bit of grass just above my fingers. Unless it is completely unentangled with the fiber and just lying on top, trying to remove it at this stage will just mess up the locks. Wet wool tends to both stretch and hang onto what it's attached to. Dry wool lets go far more readily.)

Lightly pinching my fingers on the tip of the lock, I slide them past each other. I'm not rubbing. I'm lightly compressing—with the intention of loosening the dirt more than of manipulating the fiber. I do this when the lock is submerged. It works best that way: quickest and most thorough.

Here's what the same tip looks like when I'm done:

You can still see a little darkness from the dirt, but it's much more diffuse. Less is more.

Then I change waters and add roughly half as much cleansing solution to the next bath. (If the fleece is caked in dirt, I'll use a little more cleanser all along and may do three washes.)

Flipping is definitely optional

Occasionally, in order to get at the tips that I've placed in the lower part of the bath water at the start of this all or because I simply want to see the whole range of the fiber, I'll gently place my hands above and below the mass of wool and flip it over like a pancake. Sometimes I drain and flip; sometimes I flip while the wool is in the water. It's always a delicate motion, and I don't by any means always do it. The risk is that I'll lose lock formation. The technique is most useful with Down and meat-breed wools, which are most likely to have badly dirt-caked tips and where maintaining lock formation is least likely to be successful or desirable in any case.

Here's a batch of a type of fleece that this treatment (extra soaks and wash baths, tip manipulation, and flipping) was made for:

Yes, it washed up beautifully! That's just the first soak up there. You'll notice, however, that in this situation I only used two of the big trays. That gave me room to move the trays around without using the extra space outside the tub; I just didn't want that much grubby water having an opportunity to spread. (After any washing session, the tub is exceptionally clean because it gets a full Bon Ami scrubbing.)

Take a look at the way the locks are sitting in this series of photos and you'll see that I've flipped the batches:

I delicately re-distribute the wool in the baths after flipping. That's most obvious on the small tray, where I've also already loosened the dark areas (stuck tips) that were revealed by the flipping.

Soaking rinses with clean water

I do two soaks with clean water at the rinsing end of things. Some people use rinsing solutions as well at this point. I don't, although I have no feelings either way about that. I do two final rinses because I want to make sure all that's left at the end is wool and water. I'm not looking for an excruciatingly uniform result. I'm looking for a point when I'm convinced that any "dirt" that remains is clean "dirt." Sometimes wool will be slightly discolored by minerals in the soil. There are all sorts of reasons it won't look like it's been washed to sparkling and colorless homogeneity. That's all okay. The mud, dust, grease, and suint are gone.

It's ready to get dry.

By the way, if you need to go walk the dog or something while the wool is in its final rinse, you can. There shouldn't be anything left on the wool to cause problems if the water cools off, although I do like to move it along to the drying phase without delay.

Part 3

In part 3, I'll run through a quick series of photos that shows the progression of cleanliness through the series of soaks, and I'll show you how I dry the wool.

July 27, 2013

One way to wash fleeces, part 1, getting ready

It's been quiet around here because life events have needed all my attention. Fortunately, I've had some time over the past ten days to let some of recent turbulence settle and to begin re-establishing an equilibrium that isn't braced to handle a tidal wave that can be seen approaching. That doesn't mean the storms are over; they aren't. But I'm in a bit of a breathing space, with about a dozen blog posts in the background waiting to be finished (or started).

Today I'll warm up with a topic that came up recently on Twitter: how to wash a fleece of a type that is known to be prone to felting. This is the inquiring fleece-washer's first fleece. (By the way, it will be just fine. The fleece involved, a Hebridean, won't likely be stubborn about holding onto either its grease or its dirt.)

Part 1 of 3

My general washing practices take the potential for felting into account, and I use them with all types of wool. In these posts (I see there will need to be three, as the words and the photos have added up), I have done my best to use a sequence of pictures from the same washing session, although I needed to insert a few non-sequential photos to fill in particular points. I'm also going to show and talk about at least one thing I used to do that I don't do any more, and why: your washing situation may require it, as it may require other adjustments along the way.

I'll also go into a whole lot of detail, because it can be unnerving to wash one's first fleece, and I think more detail may be reassuring as long as the novice fleece-washer keeps in mind that there are only two esssential things to remember:

Don't agitate the wool.

Don't let the water cool off so that the dissolved stuff recongeals on the fiber.

My goal is to remove the lanolin and as much dirt as possible without drying out (or felting) the fiber. I don't pay much attention to vegetable matter during washing, except to note how much there is and of what type(s), for future reference. With few exceptions, it's easiest to remove vegetable matter when the wool is clean.

I make many choices that are very personal. I hand-wash in batches that let me see the wool as I'm working. I want to start getting to know the fiber at this stage, and I want to be able to ease out some of the dirt that might not be released if I were cleaning larger quantities or containing the fiber in bags (although I use bags in part of the drying stage).

There are myriad ways to clean wool. Some people prepare net-wrapped rolls of individual locks. Some wash in big bags. Some use the container of a washing machine as a basin. Some use methods similar to mine but with fewer rinses and washes (maybe they generally have cleaner fleeces to work with!—with some of the breeds I enjoy spinning, I don't have the option of a super-clean starting point). All of these are appropriate choices for certain situations.

There is also the so-called suint method, which some people like a lot but I don't intend to try, again for personal reasons. I'm allergic to mold and mildew. I dislike strong, bad smells (barnyards are fine; feedlots and other odor-sources of similar intensity are not). And while I'm willing to accept the risk of fleeting exposure to small amounts of agricultural chemicals (like sheep dip) when well diluted by water that is continually freshened, I'd rather not spend time in the vicinity of a solution that contains (with the recommended repeated use) increasing concentrations of those unknowns.

So: I like to wash wool in the way I'm about to describe. It takes some time, but not an inordinate amount. It gives me access to quite a bit of knowledge of the individual fleece while I'm working. There's a rhythm to it. It suits the layout of my house reasonably well. And I find it rewarding to fully experience the transformation from raw substance to clean working material. Every time.

I'm going to overuse some words. One of them will be "gently." There's a reason I'm not editing out the repetitions. There's much less direct work in washing wool than you might imagine. Moving the water around is the big piece of it.

________

The entire normal sequence during which I need to pay attention takes on average 2 hours, give or take a little. It involves three stages:

Soaking in clear water. (Usually 1 or 2 cycles.)

Soaking in cleansing solution. (Possibly 1 cycle, usually 2 cycles, sometimes 3.)

Soaking in rinse water. (Maybe 1 cycle, usually 2 cycles.)

Each cycle is about 20 minutes long.

When I begin with a comparatively clean fleece, I can complete washing in about 1 hour (one cycle of each type) and be completely done (on the racks and drying) in 1.5 hours—1.25 if I don't get distracted by anything else while I'm washing (that's rare; I almost always get a little distracted). Because I do other work while the wool soaks (things that can be accomplished in short chunks of time) and am not maximally efficient, I plan on having at least 2.5 hours available before I need to be somewhere else. An especially dirty fleece will require extra initial soaks or washes (stages 1 and 2). And I always end by giving the bathtub a thorough scrubbing when I'm done for the day.

While my goal for each cycle is 20 minutes, sometimes after the timer has rung I finish the other task I'm doing and don't change the water for 25, or maybe even 30, minutes. If I'm in a hurry and have a comparatively easy fleece to wash, the cycles can be 15 minutes long. Whatever the length of the cycles, however, the goal is not to let the temperature in the baths drop significantly throughout the entire wet-wool time.

IMPORTANT NOTE 1: If the natural protective substances you are dissolving off the wool with the warm water and cleansing solution get redeposited on the wool, as will happen if the water cools off enough, the resulting—now chemically altered—substance can be difficult or impossible to remove. This is especially true for fine wools, but I don't risk it with any wool.

IMPORTANT NOTE 2: Felting occurs when you produce some combination of WOOL, WARMTH, WATER, AGITATION, and SOAP.* If you're cleaning a fleece, you can't avoid the wool and the water, and you probably want to use a cleansing agent (whether it's soap or not), so what you have most control over is the temperature and—most important—agitation. Guard against agitation. A lot.

* Why might wool felt while it's still on a sheep? Let's see, I haven't had time yet to research this fully, but it might be because there's WOOL, body and environmental WARMTH, atmospheric MOISTURE, RUBBING or FRICTION from movement, and a natural SOAP-like substance produced when the lanolin and sweat salts that protect the fibers dissolve in the aforementioned moisture.

Aside: If you have especially hard water, you will get better results if you add a water-softening agent.

_____

The basic plan

So here again is the outline of the washing process:

Soaking in clear water. (1 or 2 cycles.)

Soaking in cleansing solution. (Between 1 and 3 cycles.)

Soaking in rinse water. (1 or 2 cycles.)

_____

Here's a newly acquired fleece with moderate dirt levels:

Here's a portion of that fleece after washing:

Pretty, isn't it? It will be scrumptious to spin, too.

Although I don't take meticulous care to preserve locks while washing, I don't jumble the wool around, so it ends up still pretty much in lock formation. I can then comb, card, spin from the locks, or do whatever else I would like. Admittedly, the fleece above is a Border Leicester, so the locks are easy to both see in a photograph and keep in shape during washing, but the general principle applies to any wool.

____

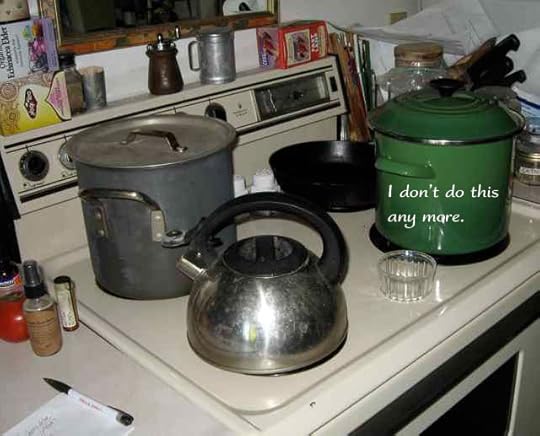

First comes something I don't do any more:

When I was using dishwashing detergent for my washing, I heated water on the stove to raise the temperature in the baths, and carried lots of boiling water from the kitchen to the bathroom. I'd worry about spilling (or dumping) the water every time I had to step over a sleeping dog to get through the hall. Plus it was a lot of work: filling and refilling the kettles, rotating which one I was using, hauling.

This was a major reason that I changed to using a cleansing aid that works at lower temperatures, like what normally comes out of the hot-water tap (about 125–135°F [52–57°C]). It made a huge difference in the time and effort required, and the wool is cleaner.

____

Second there is the matter of containers for washing, and this may be the part of washing-prep that involves the most creative advance thinking, but once you've solved it, you've solved it.

When I washed my first fleeces about 40 years ago (!), I would run water into a bathtub, put in a whole fleece, and then start wrestling. I'd push the fleece all the way to one end of the tub and hold it there while I drained the water out of the tub or (slowly) let it refill from the faucet. It took longer. It's riskier than the process I use now—more chance of running water onto the wool, which encourages felting; more opportunity to mess up the lock structure; more pressure on, and potential agitation of, the wool while it's wet. I never got into trouble using that method, even when I washed star-felters like Karakuls, but also don't want to work that hard any more. (Washing a lot of fleeces is still hard work. It just doesn't need to be made harder. Washing a little bit of fleece is no big deal at all.)

For small batches of wool, I have collected size-matched pairs of colanders and bowls from second-hand and outlet stores:

The pieces came from as many different sources. I learned not to count on memory to identify potential "matching" sets. I carried measurements with me from store to store as I collected. I still use these for small amounts of fiber, or small batches of varied fibers for sampling. The quantities they hold vary pretty dramatically, which is handy.

But for larger amounts of wool, I use sifting boxes intended for use with cat litter. The pairs consist of a lower, solid tray and an upper tray with a perforated bottom. The pieces are shown here after a washing session, with the solid bits turned over so they'll dry quickly. You'll see these in action throughout the images to come.

I have two different sizes. I found all of these at close-out stores. They actually come in sets consisting of two solid trays and one perforated one. As you'll see, I use the extra solid trays for temporary working space, although they're not essential. I haven't been able to find more of these sets recently, so if you can't locate such things you may need to consider what types of containers you can find or make that will do the same job. Just keep in mind that the part with the holes is the most important component. Water needs to be able to drain out fairly quickly without disturbing the wool.

Cast a creative eye around. I didn't know when I began my search that I was going to end up on a colander hunt, or going to every BigLots! store within fifty miles, whenever I had a reason to be in the area, to buy up its stock of cat-litter pans. I found the smaller size more recently at a Harbor Freight store. If desperate, I would start looking for two solid items that would fit together and would drill holes in the bottom of one of them. Be careful that what you choose is lightweight. It will be heavier with wet wool in it.

I also use, as you'll see when we get to the drying stage, lingerie bags (which I've gotten at dollar stores) and stacking sweater dryers.

Oh, and I do use rubber gloves. The sturdiest kind. I've worn out a bunch of the lighter-weight ones. Gloves aren't essential. I don't use any substances in this process that I'm not comfortable putting my bare hands into (although I always wash my hands after handling grease wool). I'm just more comfortable putting on a pair for most of the operations, because the water's a little hotter than I like to keep my hands in for long and as you'll see I manipulate (but do not agitate) the wool. The gloves also keep my hands from drying out excessively when I'm doing a lot of washing. Which I usually am.

For a cleansing agent, you can use any number of things, from hand-dishwashing detergent to shampoo to substances specially formulated for fiber. I would warn you away from laundry detergents. Most of them have a lot of additives and are harsher than is necessary. Hand-dishwashing detergents and shampoos raise a lot of suds that are hard to rinse out. Specially formulated fiber-cleaners have worked by far the best for me, and I like Unicorn Power Scour, which has been made not just for fiber but for raw fiber. It's low-sudsing, highly concentrated (not much is required), gentle on the fibers and my hands, and works well in water of moderate temperatures. There are other options that I hear good things about that have been formulated to work with fiber straight off (or on) the animal, notably Orvus Paste and Kookaburra Scour.

____

Deciding on how much wool to include in a batch

This is one of the ways I roughly gauge how much wool can go into a batch. The three pairs of trays that I'll be using (that's what fits in the tub) are under that bunch of fiber, but there's no water in them yet. I've just flung a layer of fleece across the dry trays. The goal is "full but not too full." I don't want to waste time, but trying to cram too much in makes it harder to get the fiber clean. Most fleeces can be done in one, two, or three batches (small, medium, and large fleeces). Only an enormous fleece will take more than that. The photo shows half a fleece.

The idea is that any extremely dirty (especially dung-caked) and matted fiber has been skirted off, by the seller or by me, before I start. Still, fleeces can be quite dirty—and this one was. Sheep live outside. Some of them live in climates that are wet and muddy (this one did). Some have fleeces that are full of windblown dust. While coated fleeces can be lovely, it can also be a source of great joy to release wool from its burden of dirt and grease and see it shine more brightly at each stage of the washing and drying sequence.

I can already see as I lay out the fiber which portions are going to need more attention. I'm sure you can, too!

Another way to determine how much wool to wash at a time is to pull off clumps and start laying them into the trays. The tray below can accommodate a couple more clumps (it is, perhaps obviously, a different fleece than the one in the first photo).

If it's a type of fleece that's especially dirty at the tips, I may try to arrange the locks so the tips begin facing down (near the bottom of what will be the liquid).

Here's that second fleece, with full containers but not yet any water.

The amount ends up fluffy up to, or maybe slightly beyond, the edges of the trays.

Here's some Jacob, at the maximum amount I ever consider.

Less is more, although once the wool is wet the amount shown above can be easily immersed in the quantity of water the trays will hold.

Dirty wool: Less fiber in relation to the liquid.

Relatively clean wool: You can push the wool-to-water ratios higher.

Part 2

In part 2, I'll cover the wet parts of the washing. In part 3, I'll run through a quick series of photos that shows the progression of cleanliness through the series of soaks, and I'll show you how I dry the wool.

If you're thinking about washing a fleece, start pondering ideas for washing containers. It's okay to start small: with a couple of handfuls of fleece in a couple of colander/bowl pairs.

June 21, 2013

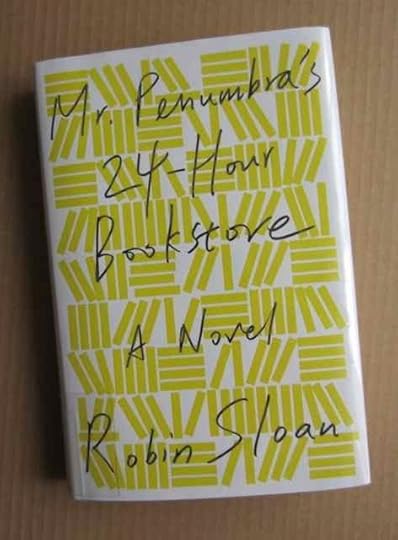

Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore

I love this book.

But only in the print version.

When I recently had a lot of travel to do, I borrowed an e-reader from the library. My daughter noticed that Robin Sloan's Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore, a novel, was one of the titles loaded onto the device's memory, and she recommended it to me.

Determined to see what I thought of an e-reader in general and this one in particular, I deliberately created a situation where I was stuck without a paper-and-ink book for part of the trip. I opened the file for this title, tried to read it, and decided the narrative felt cold and mechanical and that I would never develop any interest in, or empathy for, the main character. My daughter can tolerate some strongly idea-based books that I find tedious, and I pegged it as one of those. I quit after about the equivalent of fifteen pages. (I usually set fifty pages as my "trial amount" in a print book, but I find any quantity of text harder to gauge in e-format.) I ended up instead happily reading parts of Tina Fey's Bossypants. I didn't finish that book, and would like to. But it was episodic and immediately witty enough to survive the format.

When I got home, one of the library books my daughter had left for me to consider reading was Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore. I was dubious. She'd forgotten she'd mentioned it to me in the previous context. She assured me it was good. I needed to grab a book when I was going somewhere that would potentially involve reading-appropriate types of waiting (rather than knitting-appropriate waiting), I needed something that would be diverting and not dismal, and that was the one I shoved in my bag. (Along with one of Alan Bradley's Flavia books, as backup. Just in case.)

Well!

Mr. Penumbra is a completely different experience in print.

Among its topics are technologies (old-style and electronic), ways we discover things about the world around us, typography, and (toward the end) even some knitting. Also about making things by hand or through computer-power. And human relationships and power dynamics and. . . . That's just skimming the surface. It's an entertaining and thoughtful book, and not at all cold and mechanical.

It has earned a space on my short shelf of favorites. That's a library copy above, indeed, but there will be a personal copy added to the household library by this evening.

IN PRINT FORM.

The jacket design, by Rodrigo Corral,* is kinda magical. That doesn't translate to the e-version, either. In fact, you can't experience it unless you have a physical copy of the book (looking at an image of it online won't do the job; even looking at it in a bookstore probably isn't adequate).

____

*Cool. He also did the cover for Jeannette Walls' The Glass Castle.

June 10, 2013

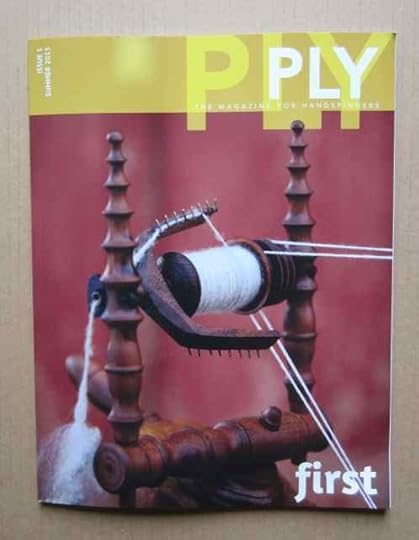

PLY magazine has arrived!

There's way too much going on around here, and I have posts-in-mind about Kentucky, and Estes Park, and some of my research into Shetland sheep, but meanwhile I've been, instead, writing things like my mother's obituary. As much as I love the other parts of my life, family comes first. (What's bigger than "love"? I don't know. But that's what goes in the second half of that sentence.)

Last night, I arrived home from the Estes Park Wool Market and the North American Shetland Sheepbreeders' Association's annual meeting in time to attend a local theater group's performance of David Mamet's Oleanna as a staged reading. Because I have season tickets and didn't have time to check the particulars of the evening's schedule, I didn't realize until I got there that it would be a Mamet play, which, to me, means (1) emotionally fraught and (2) things will not end well. Not exactly what I need right now. However, I made it through the event, which was acted and directed in interesting ways.

Then today's mail brought something much more cheerful and encouraging: the first issue of PLY magazine!

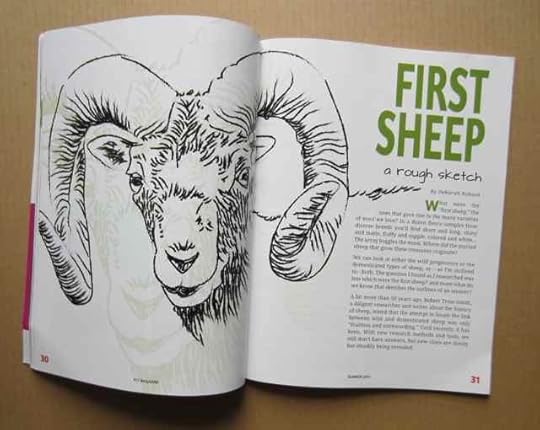

The topic of this first issue is "firsts," and it includes an article editor/publisher Jacey Boggs asked me to write on "first sheep." There are a lot of other firsts, including how to buy a first fleece, who might have been the first spinners, what was the first spinning wheel, starting a fiber guild. . . . It goes on. I'd list the contributors, but really, you just need to get the magazine.

Here's the introduction to my article (and there are great sheep photos later on, including the wild sheep species that either definitely or probably did, and most of those that did not, contribute to our domesticated varieties):

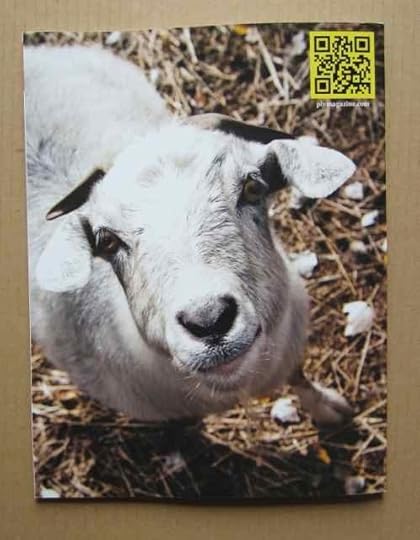

Back cover, irresistible:

Intended for the very curious spinner with a bit of experience—enough to enjoy the types of questions asked, and the variety of personal answers offered.

It's a gutsy thing putting out a magazine, even an established one. It's beyond comprehension to start a new print magazine at this point in history. As Jillian Moreno, now on the editorial advisory board, said to then-prospective editor Jacey, "You are nuts—it will break your heart. Let's do it." Part of what I love about the fiber community is the number of people within it who go ahead and do things that require intelligence, risk, compassion, and nerve: where the fully realized heart requires jumping off the cliff.

I look forward to reading PLY #1 cover to cover.

June 1, 2013

All shall be well again, I know (Julian of Norwich)

Allene Robson (locally known as Mom, or, by some, Gramma)

May 19, 1924 to May 31, 2013

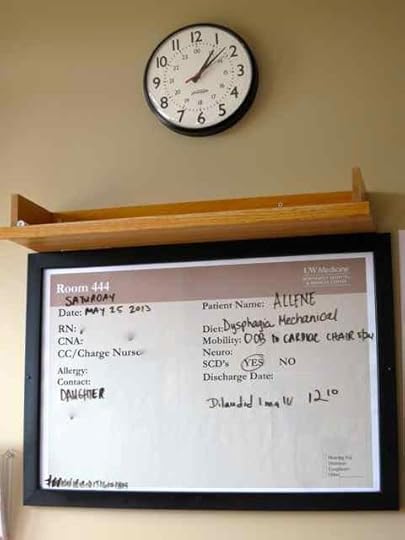

May 20 to 25, 2013 - hospital: broken hip, clear directives in place for what she did and did not want in the way of medical intervention

May 25 to 31, 2013 - Serene Corner, Kenmore, Washington - back to familiar people and place

The day after Mom moved from the hospital back to where she's been living for most of the last year (a wonderful adult family home), I took my usual afternoon walk and snapped some photos that reminded me of Mom.

May 28 to 31, 2013 - with special thanks to Evergreen Hospice

She made the world a better place—past, present, and future—in ways that we know about and ways that we don't: quietly in charge of her life and her destiny, to the last breath, despite all obstacles.

Journey well, Mom.

Love you forever.

___

Many thanks and eternal gratitude to Cynthia, Tita, Danny, Chris, Joe, Patricia, Jeff, Pat, Ben, Bessie, Susan, Melanie, Justin, Pat, and the rock-solid family Mom built.

May 11, 2013

Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival 2013, a random report

I love the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival. I love other festivals, too, but Maryland was my first wool festival (many years ago, when it was substantial but significantly smaller than it is now), and always gives me a feeling that I'm going home to a place and a community (of humans and animals) that exists fleetingly but regularly. I've almost always worked when I was at the festival, either in the Interweave Press booth, or researching and gathering materials for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, or, last year and this year, teaching.

For two reasons, this will be a brief and random report on Maryland 2013. First, I'm home just long enough to prepare to teach at a new-to-me festival, the Kentucky Sheep and Fiber Festival. (There are still a few spaces left in the two-day workshop, 3Ls and 3Cs—it's about a variety of related sheep with diverse wools both from the UK (Leicester Longwool, Border Leicester, and Bluefaced Leicester) and from New Zealand and Australia (Coopworth, Corriedale, and Cormo), and about how breeds are developed and determined, all with fiber in hand.) Second, I have very few photos from the five days because I was teaching. (I do have a few, thanks to some participants in the groups. But when I teach, I teach.) I had Saturday morning and Sunday afternoon "off," so that's pretty much when I was able to take pictures. And meet up with people I had appointments with. And buy fleeces for future workshops.

One thing I always like to do at festivals is visit the animals and see what kinds of photos I can capture. This Corriedale and an Oxford were amazingly friendly every time I stopped by (which was as often as I could).

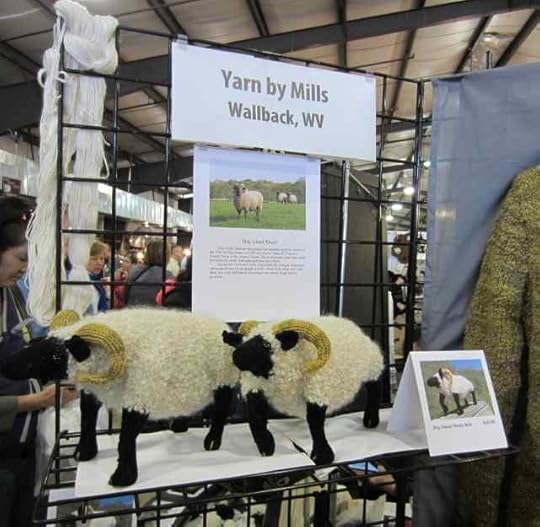

While zooming through the Main Building (which I still think of as Building V), I spotted these Hog Island sheep (a rare breed), available in knitting-kit form:

I was especially taken with the variegated yarn for the horns. The kits are produced by Yarn by Mills. They aren't on the website yet, so if you're intrigued you'll need to e-mail Margy Mills at yarnbymills AT yahoo.com to ask about them.

Then, of course, I had to visit George Washington's Mount Vernon Estate's Hog Island sheep, located as usual in the breed display section of the barns.

Here's another photo:

One of the ewes was being placed with a new young owner through a program that puts rare-breed sheep in the care of young shepherds, and the young woman who would be taking the ewe home showed her (with help from Lisa from Mount Vernon) in the Parade of Breeds on Sunday afternoon:

Hog Island sheep have quite the story to tell. I'll be including the breed as one of four locally sourced wools in a four-day retreat on Maryland's Eastern Shore in late October of this year.

I also bought two Jacob fleeces with different characteristics for the same retreat.

And got some photos of Jacobs. They tend to be very photogenic, as well as nice sheep!

This wee one seemed to have been hand-carried throughout the festival, as far as I could tell. I kept seeing it, always with an accompanying human.

I got in a quick visit to Clara Parkes' gathering for people involved with the Great White Bale project (I'm an armchair traveler):

It's all about the fiber.

That's the first yarn spun from the Great White Bale.

It's Merino.

I also got to see my friend Moe, who's a Shetland ram. He dressed up for the Parade of Breeds on Sunday.

I also got to sneak away for part of the shearing demo. Kevin Ford blade-sheared. . . .

And then Kristen Rosser, who is working with Emily Chamelin, showed how the job gets done with electric shears (she commented while Kevin sheared, and he commented while she did).

Emily and I managed to meet up on the fly and talk sheep, which was one of the highlights of the festival for me although I don't have photos—just a great link.

On Saturday afternoon and Sunday morning, I led barn walkabouts, which are a whole lot of fun even though they involve a bunch of on-the-fly changes of approach and plans (depending on what's happening in the barns). We alternate walking through the barns and looking at specific breeds of sheep, while either I or the shepherds talk about them. . . . (Thanks to Joanne Jaeger for the next photo.)

(That's Melissa Weaver Dunning, with whom I had the great good fortune of spending a fair amount of time during this festival. She teaches at John C. Campbell Folk School, among other places.)

. . . and finding a quiet place to discuss questions that have come up or give an overview of what we'll be seeing next. (Thanks to Melissa Weaver Dunning for this next photo.)

We did the walkabouts for the first time last year, and there were a few scheduling tweaks that made them work better this year (like: not trying to do one during the Suffolk lamb auction in the same building!) and a few logistical shifts that made them a little more challenging (lots more breeds on display—like more than 40!—which meant one of the aisles was very narrow, but we managed).

When I worked the festival at the Interweave Press booth in years past, representing Spin-Off magazine, I used to go to the breed barns to take a break—there and to the sheepdog demos. I didn't have a free moment this year during any of the dog events, alas, so I missed them entirely.

But I did find a few fleeces to bring home for teaching workshops this year.

And more.

ALL of this wool will be distributed to other people, mostly in workshops. Well, I'll get to make some swatches as part of the ongoing research. Yesterday I washed up the first two bathtubs-full.

Wow, do I love the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival!

And next week I'll be at the Kentucky Sheep and Fiber Festival, which I'm looking forward to experiencing for the first time. I hear there are still a few workshop spaces available. All of my workshops sold out at Maryland, and it would be fun if the one in Kentucky did, too! I'm bringing plenty of wool (including some of what's drying downstairs right now), so as long as there's an opening even walk-ins will work.

My, this is lovely wool. I can't wait to share it.

Okay. I need to go wash more of it.

April 23, 2013

Tussah: 19?? - April 23, 2013

We were Tussah's third home that we know of. She lived with us for eight or nine years. She was somewhere between six and eight years old when she came to us.

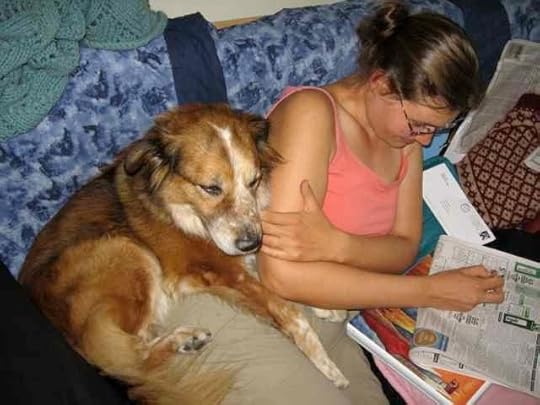

She had initially been abandoned at a reservoir in North Dakota. From there, someone picked her up and took her to the humane society in our area. She was adopted from there by people who were able to give her a good home as long as they lived in the foothills and let her run. They adopted two human children, moved to town, and didn't have time for the dog, whom they kept closed off in a shed after she'd eaten a deck and some trees. She managed to get out of the shed and to scale six-foot fences, repeatedly, looking for companionship. Their vet finally talked them into allowing her to be re-homed. At the time, we weren't ready for another dog, and several people were anxious to take her on but for one reason or another couldn't right then. We offered to foster her until a home could be found, and put her on the waiting list for a no-kill shelter in the area. The shelter never called. Before long, we wouldn't have let them have her anyway.

She helped write The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook (with Ariel).

She preferred to have company when she ate. Ours.

If we were going somewhere, she wanted to go with. And she was a very good traveler.

Wherever we were, that was home.

Just the right size for a lap dog, but never insistent, always invited.

With my aunt, my mother, Ariel, and me, in Long Beach, Washington.

Picnics were good (again with Ariel).

Or any time we were all together. Which was most of the time.

Especially liked wading: this is Long Beach again.

And a local farm pond. Happy to putz around. Not so eager to actually swim.

Superb at enjoying whatever was happening at the time.

And exceptionally good at basking.

Learned to walk on a leash early on (she didn't have that skill when she came to us) and enjoyed the twice-a-day outings, as well as longer hikes. (Here with Ariel again.)

This was the Ariel Memorial Hike, at Dakota Ridge west of Boulder.

She never met anything on two feet or four whom she didn't think would make a good friend.

But she was not fond of flies.

She always liked learning more about the world around her.

And helping others do the same. At times like this, we would say, "She misses her shed. . . ."

The next photo was taken about fifteen minutes after we'd been introduced to Ceilidh at the meet-and-greet set up by Western Border Collie Rescue. Our primary criterion for a new member of the family: Must Not Harrass Tussah. Ceilidh went home with us, and while she taught Tussah a little bit about how to play, she never harrassed her for one second.

However, they did have different opinions about how much sniffing needed to be done (Tussah = more) and whether it was time to see whatever was next along the trail (Ceilidh = now).

At the top of the mountain.

Helping out at the Puppy Up! walk to raise money for canine/human cancer research. It was a very windy day (with Ceilidh).

Tussah was always willing to share. She knew there was plenty of love to go around. Always.

The only thing she asked was to be able to go with.

Even if it had just snowed a foot or more. This was last Wednesday.

__________

Details:

At 2:30 this morning, my daughter woke me, saying Tussah had had another episode, consisting of yipping and slight seizure; she's had maybe a half-dozen of these over the past three months or so, and has had several incidences of canine vestibular syndrome, or CVS, since last September. However, this one was not resolving as quickly as usual, and there were some different symptoms, and she wondered if we should get her to the vet hospital. We've had her to our vet about the episodes, of course. The next step in diagnostics was going to be a cardio/neuro workhop at the vet hospital, and they already had some records on her there from the CVS experiences. While what was going on with Tussah didn't seem severe, we thought it was important to have someone examine her while it was happening. Although the vet hospital operates 24/7, when we got there it oddly appeared not to be open (locked door, no people in evidence, lights very dim), but there are two other 24-hour alternatives available to us, so after a few minutes of trying to figure out how to access the hospital we headed across town to the next-closest option. (Tussah had not been to this second facility, but we'd taken other animals there and had good experiences.)

To make a long story short, ultrasound and needle biopsy showed that Tussah's liver was severely enlarged (indicative of massive tumor) and she had significant amounts of internal abdominal bleeding. It was almost certainly hemangiosarcoma. Even if it wasn't, there was no acceptable treatment route considering her age. We could have brought her home for a few weeks dedicated to pain control. She didn't deserve pain, so we made the decision to spare her an inevitable truckload of it.

Once we got home, I napped a bit, read some about hemangiosarcoma, and am now only more relieved that we were not seriously tempted to take her home to hope for the best. There wasn't any "best." The potential diagnosis also correlates with many of the other symptoms that she's experienced over the past six months or so. The vet and tech at the emergency clinic were fantastic. They took thorough, gentle care of Tussah and gave us clear, even-handed information, and plenty of time, although the decision we needed to make was pretty quickly clear. It was as good as it could get, for something that was so sudden and drastic.

__________

Tussah was the sweetest dog on the planet. We're so fortunate we were able to share a good portion of her life with her.

Tempest's Tussah Redfurr

— thank you for everything, T-bear. You are a treasure.

April 10, 2013

Types (and groupings) of wools

On Apr 9, 2013, at 12:48 AM, A. N. Mouse wrote:

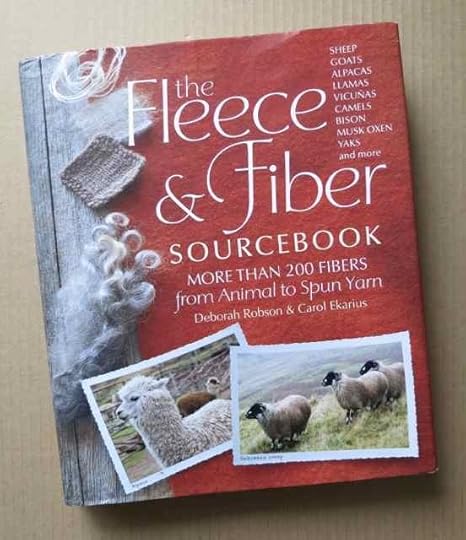

Subject: Types of wools from Craftsy, and Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook

Hi Deb,

I just watched your Craftsy class last night, thanks so much for doing that, it was excellent for a new spinner! I just have a question regarding a comparison between that and your Sourcebook.

In the Craftsy class, you talked about four general classes of wool and some of the major representative breeds in each class. Do you use the same general division in the Sourcebook, so that I would be able to tell which class various breeds fell into? Or, alternatively, I assume there's enough parallel information that I can bridge from the type description at Craftsy, to any classification you might use in the Sourcebook?

I find I want to spin All The Things, but at the same time I want to have some rationality about what I'm doing while I'm doing it!

Many thanks and best regards

A. N.

__

Dear A. N.:*

Thanks so much for your note, and I'm delighted that you enjoyed the Craftsy class!

You ask a very interesting question, and it doesn't have a simple answer. However, it does have a workable one.

The Craftsy class was very simplified, and its primary audience is both knitters and spinners, with a slight bias toward knitters (also crocheters, weavers, and so on). The wool-type groupings I used in the Craftsy presentation are aimed at people whose primary contact with the fiber is in touching the yarn (usually by squishing the skein!) and who want to then knit, crochet, or weave something that doesn't disappoint them (too soft or too harsh to function well in what they decide to make).

The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook has not been "distilled" to the same extent, and its groupings are different—they reflect a more comprehensive view of the sheep and their wools, and were developed in large part because I wanted to be able to consider related groups of wools together—and, most importantly, to help myself (and other people) more readily differentiate between sets of breed names and types that get confused. Fleece & Fiber covers a lot more territory, in a lot more depth, and its information is more nuanced.

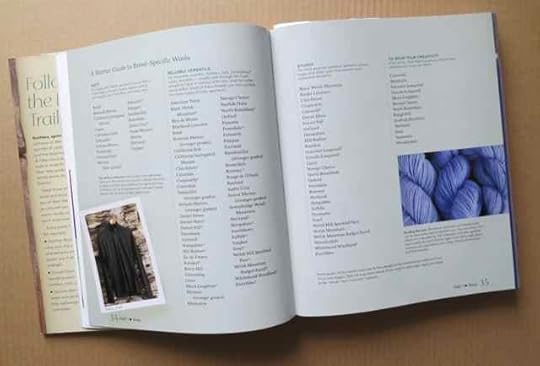

The key to connecting the types of concepts in the Craftsy class and the information in Fleece & Fiber is on pages 34 and 35 of the book, where you will find "A Starter Guide to Breed-Specific Wools" (it was co-author Carol Ekarius' brilliant idea to include this in the book, and I made up the categories and put the breeds in them).

The categories there are a bit different than the ones from the online class, because when I was developing the Craftsy course I came up with the (more memorable?) catchwords to be used in a video format to describe a smaller number of types of wools, and those groupings don't relate directly to the four lists of breeds in the book. Yet the Fleece & Fiber lists on those pages should give you the rationality in approaching the wools that you're looking for.

The study of wool, like wool itself, is not static. One of the things I like so well about learning more all the time about wool is that there are so many ways to organize and understand it. I hope the systems and terms I'm coming up with continue to help others. They're rough maps, based on my travels, to help guide others' explorations.

I'll have more ideas about how to think of wool groupings to throw into consideration in the future, as my understanding evolves. Don't take any of them as the last word: they're all sketches from a particular perspective, and they can all exist simultaneously. Use what is helpful. Skip over what is not, and instead find a different angle from which to examine what you want to get a grasp on. That's what I do. It's endlessly amusing.

With all best wishes, and happy spinning!

Deb

Deborah Robson

http://independentstitch.typepad.com

* A slightly revised and expanded response. With pictures. I like pictures. And links. Links can be useful.

_____

Congratulations to Joanne Seiff on winning the copy of Ann Kingstone's Born and Bred! I made up slips of paper and folded them and put them on the living room table and my daughter walked by randomly and snatched one out. It had Joanne's message on it. Both my daughter and I said later that we really wanted to pick EVERYBODY. But we couldn't, so thanks to everyone for throwing your names into the circle of chance. It's a wonderful book.