Deborah Robson's Blog, page 8

March 22, 2013

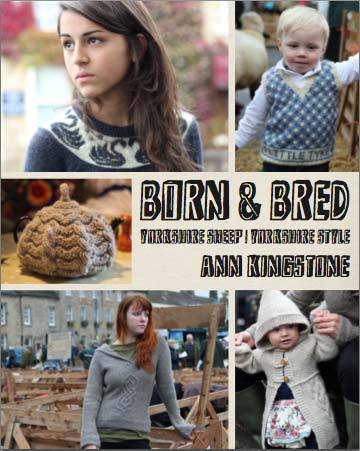

Ann Kingstone's "Born and Bred" Yorkshire-based designs

Those of you who, like me, enjoy books on the order of Clara Parkes' The Knitter's Book of Wool and Sue Blacker's Pure Wool: A Guide to Using Single-Breed Yarns have a new collection to check out: Ann Kingstone's Born & Bred: Yorkshire Sheep, Yorkshire Style (the extra links go to Ann's other collections, also good to peruse).

I'd describe Ann's accomplishment here as succinct, sweet, and a little bit sassy—while well seasoned with elegance. She published this collection in conjunction with yarn shop baa ram ewe, from which all the yarns are said to be available. (I also found some kits. Nose around the site and see what you discover, too.)

I love the way Ann has designed for a variety of styles and situations and yarn weights, producing nine projects, all of which I find appealing enough to cast on for. I found myself wishing that I'd had the hooded jacket pattern to knit for my daughter when she was small. I knitted her a hooded jacket that she wore for several years (handknits seemed to fit for longer than commercial knits did), so we didn't miss out, but what a sweet garment that is (lower right on the cover, above).

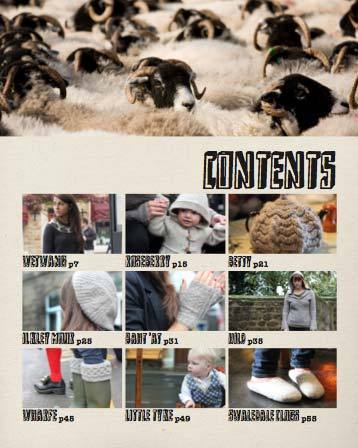

Among other things, I greatly enjoyed the connection Ann made between a number of sheep of the area (of course!) and the designs. The sheep she talks about, and some of whose wool she uses in her patterns, include Wensleydales (both white and colored), Swaledales (those are the sheep at the top of the contents page, just below), Whitefaced Woodlands (a really old breed), and Mashams, which are a traditional crossbred (composed often of Wensleydale × Swaledale, or very similar breeds). Yorkshire is where the annual and famous Masham Sheep Fair is held (it will be September 28 and 29 this year). Both Wensleydales and Whitefaced Woodlands are rare breeds.

Because this is how I think about collections of knitting patterns, here's a summary of the patterns, with quick notes about the designs, the yarn weights, and the specific yarns Ann used:

Wetwang, a pullover sweater (jumper) with graceful black swans around the yoke and lovely, subtle detailing - DK weight, Wensleydale Longwool yarn from the Wensleydale Longwool Sheepshop

Roseberry, the wee one's coat - bulky weight, Rowan Purelife British Sheep Breeds Chunky Undyed in the shade "Light Masham"

Betty, a tea cosy named after some tea shops I've been told are wonderful - bulky weight, baa ram ewe's "Rare," which is Whitefaced Woodland (yay!) combined with Hebridean (lovely stuff, too)

Ilkley Moor , a tam - fingering weight, from baa ram ewe "Titus" (Yorkshire fibers: 50% gray Wensleydale, 20% Bluefaced Leicester, and 30% alpaca—yes, the alpaca connection is explained)

Baht 'At , fingerless mitts - fingering weight, from baa ram ewe "Titus" (same as Ilkley Moor, above; the two designs are related in concept as well as yarn and patterning)

Hild, a pullover hoodie - aran weight, "Jarol Pure British Wool Aran" from Masham sheep

Wharfe, boot toppers (not just pretty but practical: keep the wellie tops from chafing legs!) - bulky weight, from baa ram ewe's "Rare" again (Whitefaced Woodland and Hebridean blend)

Little Tyke, a color-patterned vest for small people - DK weight, Wensleydale Longwool Sheepshop yarn

Swaledale clogs - aran weight, felted, from British Breeds "Swaledale Aran" (which may later be in stock at baa ram ewe, but I can't find it right now although I did find this)

The names of the designs come from places, a saint, a song (okay, DON'T miss that link! it's just over a minute, and goes really well after the longer clip at Baht 'At above), and more, all with Yorkshire ties. Even though the accompanying text is short, it strikes me as perfectly suited and it's personably informative.

Born & Bred is available in print and digital editions (Ravelry link for the digital version, with more photos of the designs). I am utterly charmed by it.

I haven't done giveaways much before, but Ann tells me we can do one and I opted for the digital edition. If you'd like your name thrown in the hat (probably a hand-knitted cap, actually), let me know in the comments. I'll figure out how to do a giveaway. I'll probably make my daughter do the drawing, so: (1) all names in by April 2, (2) drawing the weekend of April 6 and 7. Please remind me if I forget (see note about the days getting away from me in the post from two releases ago).

Oh, and I almost forgot. Yes, I did already cast on for one of the patterns and it's a fun knit. This one still needs finishing of the ribbing around the hand (in process) and on the thumb opening. I'd hoped to have it done in time for this post (well, I'd hoped to have a pair, but I always want to do more than is quite possible), however . . . I got most of the first one completed!

Baht 'At (check out the song, or Ann's book, for the meaning of the name):

Not entirely off-topic:

While I was finding links for this post, I discovered Moorland Pottery, which has a number of items I enjoyed looking at, some of them relating to sheepdogs, Herdwicks, other Lake District sheep (which look a whole lot like the Scots sheep, but then we're not talking representational art here), and what caught my eye first, the chickens in the wooly jumpers. . . . And yes, Yorkshire-themed items, including some that are "born and bred," which was how I ended up on the site.

March 20, 2013

Why Shetland sheep as a research focus?

This follows the previous post and pertains to the reason for my next research area, Shetland sheep and wool, and to the impetus behind the Dreaming of Shetland project (website to come at dreamingofshetland.com).

Donna Druchunas sent a link to some fantastic photographs of Shetland and of sheep on Shetland.

Deb:

GORGEOUS pictures, and interestingly they point out some of the challenge in this whole project—or at least the sheep photos do!

The only sheep shown that I'd bet is a full Shetland is that ram with the curling horns (this is not a reason not to use the photos: all of the sheep shown grow Shetland wool because they grow wool on Shetland).

But the others don't have characteristics of the Shetland breed, most obviously the fluke-shaped tail (a short tail, narrower at its tip than at its base). That black-faced one is at least part, and possibly full, Suffolk. Some of the sheep that do have tails like Northern European short-tails don't have the Shetland body type.

COOL.

Not a reason not to use images. But I'd go with lambs or pictures of sheep in the distance or that ram.

Donna:

I guess we should include a short article about this topic because people will be wondering and interested. Would you want to do that or would it be too much? I would just want it to be "a letter from Deb" off the top of your head. Don't do any research FOR this, just outline the questions that come to your mind quickly and show why the research and further work is needed? Is that something you could do in 15 minutes or so?

[Insert a short interval here.]

Deb:

Well, more like 60 minutes, and it's definitely a "letter," not a "draft," much less finished piece. And now I need to quit, because the temptation is to revise and refine. . . .

______

Why Shetlands?

As I've recovered from the intense work involved in The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, the opportunities for future inquiry arise on all sides, and there are more fascinating possibilities than can be even listed, much less adequately considered, in a lifetime. Sheep and their wools continue to capture my interest and attention—even more than before, because of what I learned in writing the "big book." So the question over the past couple of years has been where next to invest my curiosity, since it won't be put to rest!

With about 1400 sheep breeds identified globally, I won't be able to cover them all in the years available to me, however many those are. The Sourcebook included fibers that English-speaking fiber folk might reasonably get their hands on. Natural next steps would include covering more sheep breeds from continental Europe, and that's a series of topics for which I'm collecting both fiber samples and reference books. It's a big enough area, and sufficiently complicated, that it will take years to manage. I'll be working on it.

At the same time, I've been ambushed by the Shetlands. This is a good thing. Shetlands were the most difficult breed to write up for the Sourcebook. They took the most time and raised serious questions that apply to all sheep, through all time, although not in as concentrated a form as for the Shetlands.

For publication in 2011 and 2012, Spin-Off magazine had me write up pieces on Soay sheep, Lincoln sheep, and a few puzzling aspects of wool quality. Also for 2012, The Journal for Weavers, Spinners and Dyers asked if I would write an article on the history and development of British sheep breeds. Next, for 2013, PLY magazine tantalized me with the idea of researching the origins of sheep: how they became domesticated, how they traveled around the world, how people have shaped sheep to fit particular environments and how sheep have been willing partners, able to adapt and thrive on every continent except Antarctica. I knew when I said yes that none of these would be an easy assignment. I couldn't resist the questions behind them.

As I've followed these intriguing trails, the Shetlands kept cropping up on the edges, emblematic of ideas relating to thousands of years of history, and of human/animal interdependence, and of breed definition, and of unique (and diverse) textile traditions, and of local and global economics, and of what we fiber artists pick up to spin, or knit, or crochet, or weave—and whether we will have these materials to work with in the future, or not.

Shetlands are (American Livestock Breeds Conservancy) and are not (Rare Breeds Survival Trust) a rare breed. Looking closely, it becomes apparent that whether or not the breed as a whole (whatever that is defined as) is rare, some strains of it, including some of the fleece colors, are quite endangered. Shetlands cannot be easily categorized or described.

Sheep known by one or another group as Shetland sheep grow single-coated fleeces that are very fine or medium in quality; double-coated fleeces that contain several fiber types; crimpy fleeces; wavy fleeces; and everything in between. They grow this wool in multiple countries and landscapes, in flocks shaped by differing human intentions and pressures.

Shetlands connect to the earliest sheep, and they demonstrate what happens when humans influence a breed to fit alternate environments and to respond to economic pressures—in fact, they demonstrate this multiple times, in many ways.

When I was researching the Sourcebook, it was at the point that I read a well-informed account of wools describing Shetland as a "Down" wool that I determined that I needed to spend as much time as necessary coming up with a supportable definition of "Down" wools. [Added note: In the end, I don't include Shetlands within my definition of "Down" wools.]

Shetlands open many questions, for which there are almost certainly no right or definitive answers.

But I think that spending the next year (or more) of my life exploring Shetland sheep and Shetland wool in greater detail will illuminate many aspects of how rich and interesting our fiber world is—in ways that will apply to topics as small as the hats we put on our heads and as large as the global wool marketplace.

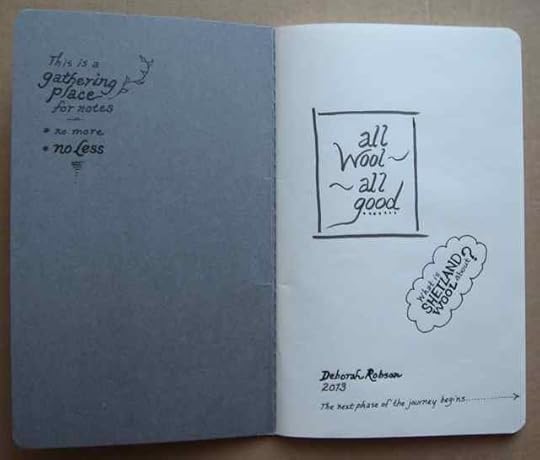

I can't wait. In fact, I haven't. I'm already deep into this project. The front page of my first notebook on the topic reads: "All wool, all good," and "What is Shetland wool about?" The study of Shetland sheep and their wool has already begun to reveal to me, and has the potential to show other people who care about these things, a lot about why it's true that "all wool" is "all good," and why we need to pay attention to both history and the future in order to maintain essential values related to being human and being responsible residents of the planet.

One bit of fleece at a time.

March 19, 2013

Dreaming of Shetland

Ah, time. There just isn't enough of it. If there were, I'd complete a lot more blog posts. I have ten started in MarsEdit, the program I use for composing, and another few dozen that I've meant to start writing but haven't even gotten as far as jotting down titles and concepts for. Often those ideas sit uncompleted because I have other work that needs to be done instead. The quiet here on the blog never results from lack of enthusiasm or a scarcity of things to share: it's an indication that the days end too quickly.

Thus the conundrum that I presented to a group of fellow fiber artists and writers when we got together in February: How to do more of the sheep and wool research that I feel called to undertake, while also earning a living? Most of the work on sheep and wool involves a lot of time for what amounts to honoraria: payments that recognize the value of what has been produced without actually providing enough to buy groceries or pay the mortgage.

The ideas these creative folk came up with surprised and floored me. I'm still recovering, and while I don't know what the efforts that were launched that evening mean yet in practical terms, the support all on its own has been so affirming that I'm challenged to just take it in. One of the ideas was presented to me with the following introduction: "We have an idea. All you need to do is say 'yes' and have a PayPal account." I had to absorb the proposal that they presented to me for a few minutes, then said, "yes," along with "thank you," and "I do have a PayPal account. It's already part of my freelance business."

Shetland

So there are two primary ideas afoot as a result of that gathering's attention to my sheepy obsessions. They both relate to an upcoming trip to the UK, which in turn has been instigated and is being facilitated by a small group of friends. The entire extended group of interested parties still hasn't resolved the visa issues involved in teaching, so this trip will be focused on research, although as the conversations have evolved other folks are stepping up and working on the paperwork part, and I may be able to teach on a future trip.

When the idea of a trip to the UK first began to be bandied about, the initial questions concerned when, and with what emphasis—which narrows down where. There are many ways to continue the research I did for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, and it would be easy to run off in all directions and end up with scattered bits that don't pull together into substantial insights. There are about 1400 breeds of sheep throughout the world and there is no way I can cover them all. I'm working, slowly, on more of the breeds from continental Europe, mostly with the help and support of people on Ravelry. That's a long-term project and one that so far has no clear boundaries. It will need to perk along in the background until its shape becomes apparent. We all knew a trip to the UK would need to be very focused in order to produce useful results. There are just too many options.

Shetland Wool Week arose as the optimal event around which to plan the trip. Over the past six months or so, I've been pushed toward intensive research on Shetlands, for a lot of reasons. Resources for deepening this research have been dropping onto the path in front of me, one after another, confirming this as a good next organizing principle. I'll have more to say about that as time goes on.

But first here are the two projects that this group of folks came up with barely more than a month ago: the ones that have left me nearly speechless since.

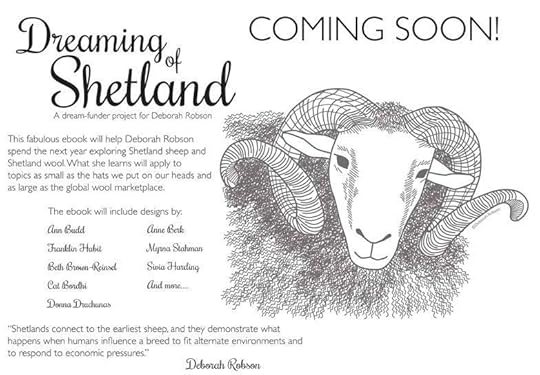

The e-book project: Dreaming of Shetland

A small crew of volunteers is organizing an e-book of patterns, essays, and photographs to be called Dreaming of Shetland to be sold through Ravelry to support my research. While a small crew is putting this together, a large number of people are contributing to the project. It's quite astonishing.

Yes, it will support me, but it will also support the sheep (all sheep, not just Shetlands), and I've been convinced it will also generate a lot of good energy for the people who are helping out, in ways large and small. So I have, indeed, said "yes" and "thank you." (I had a little practice with this earlier, in relation to a different offer. That helped facilitate this opportunity.)

The plan is that the e-book will be available some time in the early summer. Here are some of the materials that the group has generated so far. I really don't have much to do with this. My job is to keep chipping away at the research and writing that I have been set on doing anyway. Knowing that other people are actually interested in this research is a huge plus for me all by itself.

Here's a flyer that they made up to be distributed at festivals and workshops:

The drawing is mine; I've slowly been doing images of sheep, and had not done a Shetland. I didn't have time to do one recently, either, because of an onslaught of deadlines, but it seemed like an essential element of what was happening (plus I really enjoy doing the sketches), so I ended up "stealing" about 20 minutes a day over a couple of weeks to put this ram together. Drawing a Shetland is as complex a task as researching the breed!

I've written a "Why Shetlands?" letter that will be included in the book, and if I can grab the time I will also put it up in the form of a blog post. Because it's actually written, that should be possible.

Donna Druchunas and Anne Berk are coordinating the e-book project, with the able help of Susan Santos, Sarah Jaworowicz, and others: as I said, I'm doing my best to focus on the research itself and not get distracted by the fact that I can't believe all of this is actually happening.

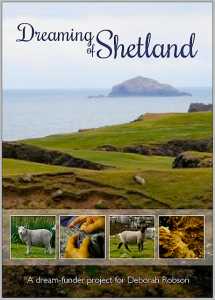

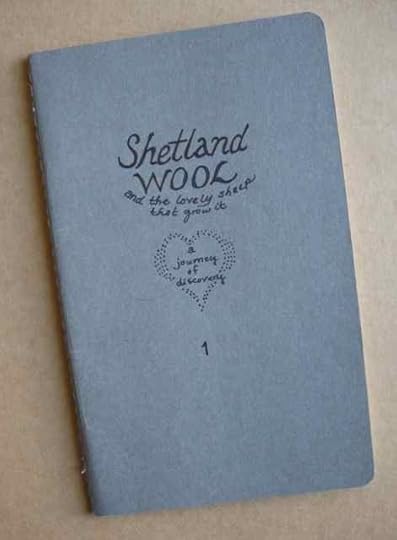

Here's Sarah's preliminary cover design:

Isn't it beautiful? I'm remembering that my job here is to admire and get back to studying sheep! The sheep shown in that lower band of images, while they live on Shetland and produce perfectly fine fiber, are not the Shetland breed. I talked about this distinction between sheep-of-Shetland and Shetland-breed-sheep in The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook on page 189. I'll be looking at the whole context, with an emphasis on the breed. There will be at least one sheep of the Shetland breed in the final cover. (Truly: I have yet to meet a breed of sheep whose wool I didn't like. The second-from-right image there is almost certainly a Suffolk, and last week I taught a day's worth of workshop on Suffolk wool, which is one of the most overlooked treasures of our fiber array.)

Here's Donna's description of the project, from her latest Sheep to Shawl newsletter:

I’m excited to be able to introduce you to a new collaborative project I am working on, Dreaming of Shetland. This will be an ebook featuring a group of incredibly talented designers who are giving of their time and talents to help fund Deborah Robson’s research about Shetland sheep and wool. Over the next few months I will be featuring this project in my newsletter and on Facebook, with updates and information about pre-orders as soon as we are ready to accept payments. I hope you are as excited about this project as I am and I look forward to telling you more soon.

There will be a related website at dreamingofshetland.com (no link because as of this writing it does not yet exist).

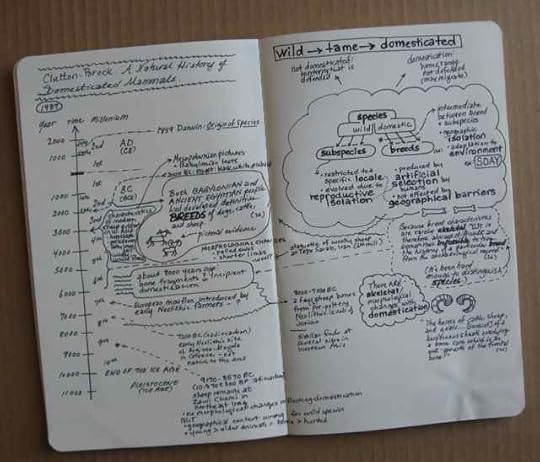

The notebooks: And a proposed inside view of the Shetland research project

At the gathering in February, I passed around a notebook I'd used to collect my research for the article I wrote for the first issue of PLY Magazine. The reason was to show part of what I've been up to and how I'm going about it. For that article, I had to leave the computer systems behind and work by hand—a practice that I expect to need to continue while researching the Shetlands. The computer was invaluable for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, and is also essential for the writing portions of other projects including the PLY article and certainly any summations I do of the Shetland research. However, where multiple small bits need to be comprehended and then pulled together, I found the visual and tactile approaches worked best.

Here's a page of the notes pertinent to the PLY article that I took from Juliet Clutton-Brock's A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals (1987):

It's essential to keep track of the publication dates of the research and commentary, because the state of knowledge is changing.

I also need to track dates within the material I'm reading. The timeline you see there is something I constructed to put observations in the appropriate sequence.

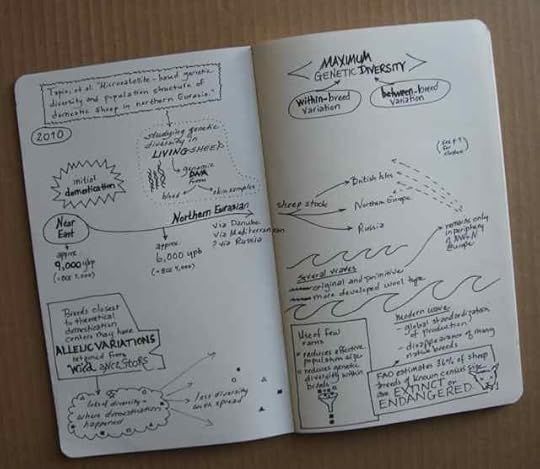

Here is one spread of notes from a later source, Tapio, et al., "Microsatellite-based Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Domestic Sheep in Northern Eurasia" (2010):

The reaction to this was: "You need to share these."

Me: "HUNH? They're just my notes."

Response: "You need to share your notes on the Shetland project while it is underway."

Not long after that, a member of the group offered to help me set up a subscription-based website on which I can post my thoughts and notes and other artifacts of the journey. We've had time to engage in preliminary conversations about this, but I haven't had time to do more than begin to consider what I might do with it.

Yes, high points of the quest will be on this blog. The subscription site will allow me to devote time to detailed coverage, which can't happen otherwise for the reasons noted at the start of this post. It will also provide interested readers with a central place to find more in-depth information about my research process, along with what I'm learning about the sheep and their wool.

In sum. . . .

There are lots of fantastic ideas bouncing around, and what I need to do now is (1) get on top of mail and finances again, following my recent return from a teaching trip; (2) see whether I can get my taxes for 2012 done without having to file an extension (haven't had time to finish up the data—mileage, inventory, and so on); (3) proof pages for The Field Guide to Fleece; (4) continue organizing all the details (and fiber acquisition) for the remainder of the year's teaching events; and (5) keep up with the freelance editing work.

At the same time, tomorrow night I will, as usual for Tuesday nights when I'm at home in Colorado, go to a coffeeshop for three or four hours. While there, I hope to be able to read and take notes on one Shetland article (maybe two? hope springs eternal). I know which one I will turn to as soon as I get my cup of tea (perhaps Ti Kuan Yin) and bowl of vegetarian soup. That article has been printed out and has been riding around in my backpack, along with the notebook, the highlighters, and the pens, awaiting the moment when I can devote my attention to it.

I can't wait to find out what piece of the puzzle that particular article will fill in. And to make a list of further sources, another task that I have been looking for time to enjoy.

March 4, 2013

A Peruvian weaving technique: ñawi awapa

Following my day of learning a few Peruvian knitting techniques, I was fortunate to have a long half-day workshop with Nilda Callañaupa Alvarez on a single weaving technique from her home village of Chinchero.

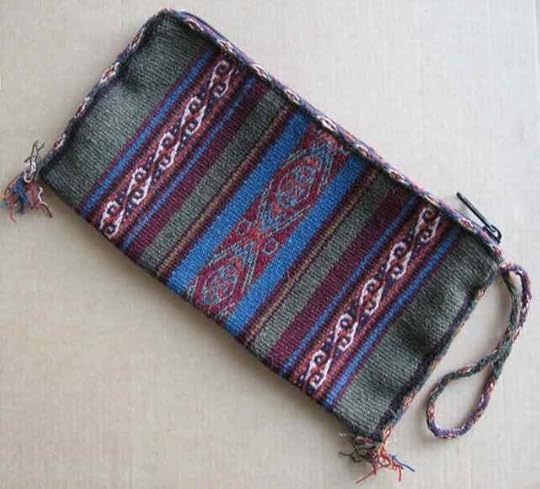

Ñawi awapa means "eye border," and it is a cord used to finish the edges of textiles, as you can see on the small bag below:

The cord protects the fabric, reinforcing vulnerable spots against wear, and produces a neat finish, and, as in parts of this bag, functions as a joining technique. It is attached to the fabric as it is worked, although it can also be constructed as a free-standing tube, as is the case for the nifty little handle on the bag above.

Ñawi awapa strikes me as the weaverly equivalent of the knitter's I-cord, combined with a variant of cardweaving, also called tablet weaving (albeit, in this case, card- or tablet-less: the similarities are in the warp-faced structure and manipulation of those warps). That's not very helpful, but if you have experience with either of those techniques it will give you a starting point for understanding. It's also like intricate braiding with the crossing of the threads held in place by the weft thread. From the perspective of weaving processes throughout the millennia, it falls into the realm of crossed- or twisted-warp, warp-faced tubular weave structures.

Enough of that.

Here's what it looks like, woven freestanding. That bit where the weft shows between the warps (right at the top) is part of what I wove. The lower "eyes," much neater, were on the starter section that Nilda supplied for me. She got us all off to a good start.

Then it was our job to continue the pattern, although she clearly instructed us to, if (WHEN) we messed up, just keep going. This isn't something you can easily unweave to correct.

This is the basic setup. That starter length is fastened to a string, which in turn is tied around my waist, like a backstrap loom. The far end has been secured to one of the legs of an overturned table. The warp is tensioned between my body and the table leg. (The tables were not entirely stationary enough to resist moving completely, but they were adequate for our needs.)

That forked stick holds the threads of the warp in order and forms a cross, with threads alternating between up and down positions. In this technique, the cross only forms the baseline for the manipulations to follow. A string is tied across the open end of the forked stick to keep the warp threads from slipping out, which would be disastrous. On my lap are Nilda's detailed instructions, which most of us spent a lot of time following precisely, one step at a time.

Sorry this view changes directions, but that's the way it goes. So did we. In addition to the forked-stick loom, we needed a temporary shed stick to hold some of the crosses in place.

You can see that I'd done three eyes (two gold and one, hiding on the other side, red) and was working on the second red eye. The two colors of eyes alternate. My eyes were nowhere as neat and compact as the ones that had been woven for me at the starting end of the cord. But they were eyes. That's no small thing.

The weft (that brown puff in my hand) always goes through the warp threads in the same direction, which is how the tube is formed. It's like sliding all the stitches of I-cord from one end of a double-pointed needle to the other before working the next round.

The unused eye color is hidden inside the tube when it isn't predominant, although it's brought up to form the very center of the contrasting-color eye.

Who thought this up??

Simply getting an eye to appear correctly is an accomplishment. Below, you see one of my Picasso-esque results, with the center of the eye off to one side. The eye above it has the center gold portion in the correct position, but for some reason (probably I didn't get the weft tensioned just right) there's a crossing strand of weft getting in the way.

Peruvian techniques are so diverse that each village has its own set. During our knitting workshop the day before, Antonia Roja spent part of her time weaving on her backstrap loom (in the image below, it's secured to, and resting against, a full-size floor loom). Then she spent most of the day weaving ñawi awapa.

What we didn't know until later was that this technique was new to her. Antonia is from the village of Pitumarca, not Chinchero, as Nilda is. Nilda had showed her how to do it the day before. Based on her previous experience with the plenty-intricate weaving of her own hometown, Antonia caught on really quickly. And at the end of our workshop, it turned out that there was a bracelet-length piece of Antonia's ñawi awapa cord for each of us to take home. What a treat! (In the photo below, Antonia's is the finer one with the more consistent eyes. Mine is the bigger, lumpier version.)

I've previously admired this corded edging on a number of the textiles from the Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco, known as CTTC.

(Sorry for the slightly fuzzy photo. I've made two attempts at shooting this decently and instead of trying again I need to get back to the work I should be doing right now. . . .)

There was a trunk show of woven and knitted textiles going on all around us as we crossed and uncrossed threads, hoping we were twisting the right selections in the right directions each time. I went home with a couple of small, very useful, objects that I will enjoy making part of my daily life. I've made a practice over the past several years of selecting one piece from the CTTC or Cloth Roads displays whenever I come across them: at the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival, Convergence, SOAR, or wherever. I've also been given a lovely bag by a friend. Understanding the work involved in making them—which I thought I knew about, but now comprehend at a whole new level—I can't believe how inexpensive the finished pieces are. Fortunately, the pricing is high enough that the weavers and knitters are able to substantially improve their lives in many ways by doing this work, which also honors and sustains their traditional cultures.

For more, see Cloth Roads again. There are new items arriving regularly. But the best way to see this stuff, if you can, is to locate a booth at a festival. Look closely. The number of textile wonders contained in a small space will astound you.

This is my day's worth of ñawi awapa. I did get to advance the warp twice because I had woven enough to need to reposition it! But I still wasn't consistently getting nice clear centers on my eyes, even at the end of the day. Then again, about two-thirds of the way through the workshop Nilda came around and told me to do it without looking at the paper. Mistakes are less important than incorporating the learning.

Maybe next time I'll be able to both skip watching the paper every step of the way and form the eyes precisely. . . .

____

(Photo of Antonia courtesy of Kris Paige.)

March 1, 2013

A workshop on Peruvian knitting, mostly of puntas!

Last weekend I took two textile workshops. This is remarkable. Mine is one of those lives where if I have time for a workshop, I don't have the money to do it; and if I have the money, I don't have the time or I'm in the wrong part of the world. I've been at more festivals and events than I can count or remember, but I'm most often the person behind the registration desk, the one driving the staff rental car into town to buy food for the participant who forgot to mention she was vegan and allergic to nuts, or the one teaching the class.

In 1990-something, I sat in on a half-day workshop at SOAR with Ed Franquemont, on a couple of Andean handspindle techniques. In another 1990-something, Stephenie Gaustad sat in a hallway during SOAR, when we both had a few moments, and taught me to spin cotton on a charkha (it was, I think, at Snowbird, which would make it 1996). In 1986, shortly before I moved to Colorado to work at Interweave Press, I took Celia Quinn's comprehensive spinning workshop under the sponsorship of the Boston Area Spinners and Dyers. What fine and memorable occasions. Most of my other recent learning has come through testing out the instructions that were about to be published in Spin-Off magazine or various textile books.

But last weekend Nilda Callañaupa Alvarez was teaching within easy reach of my home at a time when I wasn't out of town and when there was a bit of money in the bank that could be diverted. Wow.

Saturday was a knitting workshop. The only thing the workshop description mentioned was puntas, which I had learned to make from one of my editing projects, but I thought that Nilda would likely have different approaches to the process, and in any case I wanted to get to know her a little better: I've been following her work for years, and we'd met in passing at a number of fiber events but never had an actual conversation.

Puntas: literally "points," or in this context a type of edging, with many variations possible, used to begin the knitting on some Peruvian hats, bags, and other textiles. Think of them as cast-ons and picots that have grown up and gotten advanced university degrees.

The sum of my weekend experience: if you ever get a chance to take a class with Nilda, do.

Saturday we did learn to make puntas. All day. It was very cool. The varieties are endless, as are the techniques. Although I "got" all the ones Nilda showed us, I don't have a lot of faith that I'll remember how to make each of them without some refreshers. I heard a rumor that in the week after our workshop (the one just completed) Nilda would be at Interweave recording video of how to do some Peruvian knitting techniques. I trust the result will be a replacement for, and expansion on, the notes I didn't have time to take while I was learning, or the energy to jot down after I got home. Nilda is a superb teacher and her handouts are excellent. Still. These are tricky little processes.

Life is pretty crazy around here right now, so I won't do justice to the workshops in this blog post, or the next one. But I want to get something set down before yet another idea I want to share is gobbled by the press of deadlines and doesn't get into the blog at all.

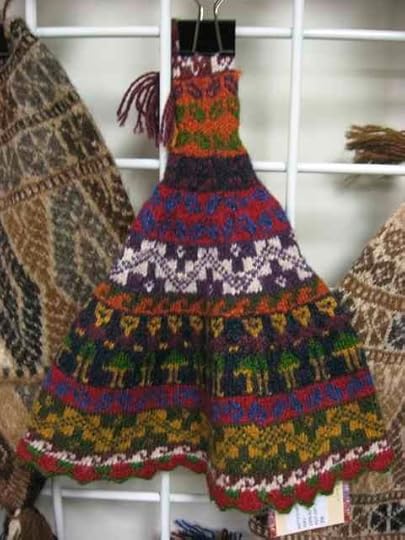

This image shows my trial versions of the puntas we learned to make (plus an inspiring little hat that was tucked into the second bag of yarn Nilda gave me to work with: we each got one, all different).

Top right are the three-color puntas that we started with (#1), and bottom right are the five-color puntas that followed (#2). As I went along, I got better at putting the color joins where they were supposed to be.

Top left is a deceptively simple little rickrack-like punta form (#3). These are the ones about which I woke up the next morning thinking, "I'll never remember how to do those!" (At the moment, I can still remember how to do all the others.) Bottom left is a relatively easy form of puntas that Nilda taught us at the end of the afternoon (#4). I think it was a reward for working the others.

She also talked about handling multiple colors of yarn, both tensioning and securing. These are things I know how to do, but now I have more options. Options always come in handy. The more I learn about textiles, the more there is to learn.

Now, here are puntas in use. Note the yarn above, which was about worsted-weight, very tightly twisted, two-ply handspun that Nilda provided for us. It's a lot bigger than the yarn used to knit the puntas on the pieces below. She thought it would be nice if we could easily see the stitches we were forming. We agreed.

Those are the #4-type puntas around the bottom of that hat.

Here's another type of puntas:

I'd need to look at them more carefully than the resolution of the image will allow to figure out which kind they are. Possibly a type we didn't cover.

The edges of this hat definitely display a punta variation we didn't do:

But the top of this little bag displays those sneaky little #3 puntas:

That's an interesting knitting technique on the bag, too. Nilda gave us a glimpse of how it's done, but there wasn't enough time to do more than enjoy it vicariously. We were too busy getting to know a few puntas.

Now one of the questions that arises is why does learning this stuff matter, either to me or to human civilization in general? For me, it's an opportunity to wonder at the number of things that people have devised to do with a material as simple as yarn: what we can fashion with, in this case, wool or alpaca fiber. For another, it's a chance to marvel once again at the astonishing ingenuity and endless creativity that people express through textiles. Especially the Peruvians. Throughout the history of the world, they have been the most prolific cultural group at devising amazing ways to construct and decorate textiles. Their accomplishments seem to me to be on a conceptual par with the greatest of modern inventions. All with very simple tools and materials.

Nilda and the Center for Traditional Textiles of Cusco (Centro de Textiles Tradicionales del Cusco) have been doing a lot to keep this body of cultural knowledge and these ways of thinking alive and vital, while providing sources of income to the weavers and knitters that are allowing them to, for example, send their children to school.

It was an honor to participate in that process in a small way.

And a friend who saw me there said, "I'm not used to seeing you this happy!"

When I'm home, I'm normally content and satisfied and interested, and also a little bit (or a lot) too busy. Simply "happy" is, therefore, apparently not something my hometown friends usually perceive. (I think I probably look pretty happy when I'm teaching; when I'm off somewhere quiet researching and spinning and knitting and weaving and writing; or when the dogs make me laugh; but for most of those times there aren't hometown witnesses.)

For the course of a weekend, though, I was able to enter a "beginner's mind" part of the textile world and discover new depths of creativity in fingers and fibers. That definitely made me happy.

Here's Nilda, checking Handwoven and Weaving Today editor Anita Osterhaug's punta progress.

There's always something new to learn.

Anita's vest is one of the products of CTTC weavers. It's handspun, naturally dyed, and handwoven. It's stunning, and it will last nearly forever. As the techniques have and will—as long as people keep learning and practicing them, even if it's just for a delightful day that ends in appreciation for the skill of the experts.

____

How to easily buy CTTC textiles in North America? Cloth Roads.

February 27, 2013

One Explore 4 opening (March 11-14 event)

There is one opening for the Explore 4 retreat in Friday Harbor, Washington in about ten days. Arrive Sunday, March 10, retreat March 11-14, depart Friday, March 15. I haven't advertised this at all because I don't want to disappoint people; there was a small waiting list and we've found space for everyone on it—in part by re-evaluating the space and determining that we could fit in a couple more people and their wheels. It's still small. If you're interested, get in touch with me as soon as possible at deb at drobson dot info.

Information is available here until some time later in the year when I remember to take the link down.

This is a view of the lodge where we meet, from the lake side.

Here's the fireplace in the great room where we meet:

We have four days, and we explore one fiber per day. This year's fibers are:

Suffolk

Shetland

yak

Jacob

Yesterday, my friend Kris came down the mountain and helped me pack up a bunch of fibers, starting from this pile, which is maybe as much as one-third of the fiber that's being prepared for the retreat, maybe a little less:

Another friend, Jennifer, has been washing wool for me in Washington. I bought it there just under two weeks ago and she offered to not only help me out by washing it but save me from having to haul it to Colorado and back again. She has posted a lot of captioned photos about her process.

Meanwhile, Debbie and Maxine from Island Fibers have gotten another several fleeces together for us. I like to source fibers locally when I can, and they're fantastic people (who will be coming to set up their moveable shop at Lakedale during the retreat). One of the breeds I wanted to feature—Suffolk—wasn't one that they'd located as a wool source on the islands before. They found us great fleeces and convinced the shepherd that the breed's wool wasn't just a nuisance! (Suffolk is fun.)

I've also gotten shipments from across the country (oh, make that the world), including this rooed (naturally shed) moorit (brown) fine-fleece Shetland that's in my bathtub right now. Jennifer and I have different washing techniques, which is part of what Explore 4 is about: finding the ways for each of us to enjoy spinning as a comfortable, ongoing, endless adventure.

If you'd like to enjoy an information- and experience-filled but relaxed time in a beautiful setting the week after next, let me know.

Happy almost-spring. The snow here is melting: so good to have water running down the streets! So good to have water!

January 24, 2013

Blogtalk radio with Natalie Redding of Namaste Farms: 2 hours of conversation!

[image error]

January 21, 2013

Penny Straker's knitting patterns

There's a Kickstarter project going right now to fund converting Penny Straker's knitting patterns into digital format. Since every little bit helps, I've kicked in my contribution. There are lots of reasons why, even on a slim budget any spare bits of which tend to go toward the acquisition of out-of-print books about sheep or wool, it took only a few minutes (deciding which level) to commit to this endeavor.

Penny Straker's designs are described as classic, and that certainly applies to garments I can put on twenty-five or thirty years after making them as if they'd been finished yesterday, and still get compliments on as soon as I walk out the door.

Penny Straker's designs also taught me a great deal of what I know about careful planning and construction of knitwear: the fine points of the craft.

What major contributions they've made to my life!

It was fun to go to the Kickstarter page, when a friend told me about it, and see a video of Penny Straker herself talking about the project. That link's the same one found in the first paragraph, and here's another that talks about the history of the Straker designs, although I'll skim across a few high points in this post.

First, though, as soon as I heard about the project I went to my closet. I pulled out the Straker designs that I still have and wear. Then I thought about others I'd made: the child's Owl sweater in lavender Harrisville sportweight yarn for my daughter when she was a toddler (when she outgrew it, I hope I sent it along for her cousin to use; it's not here; both daughter and niece are adults now); the Staithes guernsey that I made for my sister in natural dark brown alpaca; and more.

The fact that I could immediately locate or recall so many projects that owe their origins to Straker designs is a big deal. I've knitted a lot. I made all of these garments in just a few years when my daughter was young. I didn't take notes, except on the patterns themselves, so the details come from my brain cells. The experiences were remarkable, and entirely in good ways.

And when I look at the array of Straker designs, I want to make even more of them.

Second, I wondered how many of the original leaflets I could find in my rather full box of single- and small-collection paper patterns. Without as much effort as I expected to invest—like, in about four minutes—I came up with fourteen:

The copyrights are all 1981 and 1982, which means they were new when I discovered them. I've knitted most of these designs. Ten are Penny Straker's own. Four are by her mother, Janice Straker. Where links are not included below, the patterns are out of print and thus not currently available in any format. Which is a bummer. I hope and trust that it's a temporary bummer, because of Kickstarter.

These are, top row, left to right:

Jennifer Cardigan (Janice Straker), #770—sportweight, "intermediate" level—I have this one, and will show it to you in a moment; a penciled note says Borgs yarn—a reason it would have lasted well! Although I also see that I swatched for it in Briggs and Little, which would also have been a good choice. I'm dating myself with both the patterns and the yarns, and that's okay! It was splendid stuff.

Gretel Pullover (Penny Straker), #876—worsted weight, "intermediate" level—I have this one, too; you'll see it.

Staithes Guernsey (Penny Straker), #796—worsted weight, "seasoned intermediate" level—my sister has this.

Owl Cardigan (Penny Straker, more recently updated with a charming hat), #C818—sportweight, "intermediate" level—knitted for my daughter in, I see, size 4.

Blackberry Jacket (Penny Straker), #746—another one I have.

Middle row, left to right:

Tuckernuck Jacket (Penny Straker), #799—and yet another I still wear.

Becky Pullover (Penny Straker), #737-P—light bulky weight, "beginner" level—made and given away? Size 42 notes in place.

Mercedes Pullover (Janice Straker), #101—for Elite's Manhattan mohair (an unusual, because yarn-specific, design, but yardage and weight are also given)—made and given away? Size 34 notes, and a two-page letter from my mother, on blue paper, tucked inside the flap.

Potomska Pullover (Penny Straker), #740—worsted weight, "seasoned beginner" level—toward the top of my list yet to knit, along with Inverness, a candidate for the digital project that I don't own in a hard copy.

Bottom row, left to right:

Jamie Cardigan (Janice Straker), #837-C—sportweight.

Boater Pullover, adult (Penny Straker), #841—worsted weight—I made the child's and liked the project well enough to buy the adult pattern; I may have knitted it, too.

Rigby Vest (Penny Straker), #802-V—sportweight, "seasoned beginner" level.

West Bay Pullover (Janice Straker), #735-P—sportweight.

Boater Pullover, child's (Penny Straker), #C841—worsted weight, "beginner" level—made for my daughter in size 6.

I'm sure there are a few more hiding in the pile. If the patterns were digitized, I could locate them without digging through a box.

I love these originals. I love their consistent and clear formatting; their gray borders; their black-and-white photography (described by Penny Straker's own website as "outdated," although the neutral color left this knitter's imagination free to fill in with favorites).

Yet the information itself, more even than the presentation, is what's magic about the Straker patterns. Here are some of the things that have been unique, or way ahead of the pack, about them:

They are nearly all written for generic yarns, with yardages and/or weights given instead of the number of balls of a specific manufacturer's product. For handspinners, this is great and it was very unusual for the time (still is, to some extent), although I also used commercial yarns—and I'll say I chose well, as you'll see in the garments to come.

The back of each pattern contains essential basic information on how to measure, how to choose a size, basic washing instructions, and metric/American equivalents for needle sizes. The pattern overflap often contains information on yarn qualities to help the knitter choose good materials, as well as guidelines for checking gauge, and sometimes additional technical points.

Even the "beginner"-level designs are intriguing.

Pattern stitches join and flow together impeccably.

There's an abundance of technical information: techniques are clearly chosen, described, and illustrated.

From the Jennifer Cardigan description: "The Mock Cable decorates the yoke and cuffs giving the knitter the opportunity to become familiar with the pattern stitch before beginning the Raglan decreases which shape the armholes. These decreases steadily break into the Mock Cable pattern. This section of the cardigan requires a working understanding of the stitch. At the beginning of every right-side row, the knitter has to calculate exactly where to resume the all-over Mock Cable." In the "old days," we discovered these things on our own as we worked the patterns. It was fun, but it's nifty to be warned in advance. More on this in a moment, when I show you my Blackberry Jacket.

They teach excellent design practices, and are reliable guides in their execution.

Each size was test-knitted, so the detail work designed into one size carries over to the others. (Read that again and marvel.) The patterns have also been very carefully edited and proofread. If not perfect, they're extremely close to that.

I don't recall having found an error. Ever. My notations indicate that sometimes I altered the construction to eliminate side seams, but not that I found any problems. The Straker website has one pattern with errata, from a 2010 version of the child's Staithes sweater. It's always good for me to find evidence that other people who seem to be able to accomplish perfection—which I keep aspiring to, working hard to reach, and failing at—are actually human, too.

They're printed on cardstock in a weight, size, and format that can hold up to the challenges of being stuffed into a knitting bag repeatedly.

With the ability to print out new copies of a digital pattern for each use, this is not as big a deal as it used to be, but it's still worth noting. The fact that those patterns in the first photo have been used says a lot for the physical objects. Although I didn't keep many records on my knitting projects, I can tell a great deal about what I did with these patterns because I jotted notes on them and they've held up well.

The typographic design and layout are clear and easy to follow.

Other knitting designers and writers who followed have built on these foundations, but there are aspects of the Straker patterns that many could still benefit from studying. Now that some of the pattern descriptions are on the website for Straker Designs, there are a couple of plusses we didn't have with the printed versions:

Degree of difficulty is indicated. There is also now enough information to allow the prospective knitter to understand the philosophy of the piece and its design components. Interesting that I type "philosophy of the piece," but yes, that is a big part of the simple explanation that accompanies each pattern in the digital presentation, and a philosophy definitely underlies the design process that informs these pieces.

Here's a portion of the description for the Becky sweater, a "beginner" piece: "The directions are threaded with caveats, pointers and illustrated techniques to help all knitters enjoy the knitting process of this pullover." Again, we found this out by using the patterns.

I can't say enough nice things about these patterns, nor can I adequately credit the benefits they have given me as a knitter. So I'll show you a few of the things that I made from them.

Here's Gretel: decades old, and much worn. Good yarn. Great design. Lots of fun to knit. I did slightly modify the heart design (giving it more height), because I'm long-waisted, always need to add length, and wanted the hearts themselves to be very open. My graph-paper notes are taped inside the pattern, one of them bearing the inscription "shoot on black backdrop, larger photos." (That would have been film I was shooting. I have no idea why I needed the images.)

It was a yarn called NZN in a color called orchid. Although I don't know what wool it was spun from, it behaves like a fine-micron Romney. Thus it has very, very few pills, despite advanced age and wear, and yet isn't itchy.

Here's the Blackberry Jacket.

Aside #1: I had that wonderful tweedy purple yarn, from Candide, but not enough of it to make the jacket. I'd probably gotten the skeins on close-out. I worked at Webs at the time, both helping customers and filling mail orders. (Webs was not then located where it is now. It was behind the post office in an old Victorian house, the third location that I know of: (1) Elkins' basement, (2) behind the police station, (3) behind the old post office.) I wanted to use the yarn for this jacket despite the scant supply. Fortunately, I realized in advance I would run short. So I found the two other colors—the navy and . . . hmmm, I think that pink may have been a leftover bit from Gretel . . . and planned how to combine the colors so it would look like I'd meant to do so from the start. I actually think the addition of the pink lines just above the ribbing are what turn it from "doing the best I can" to "yes, I absolutely meant to do this."

Aside #2: Thanks to Penny Straker, I did shape the neckline, the sleeve openings, and the set-in sleeve caps in blackberry stitch (also known as trinity and a few other names) while keeping the pattern intact. The stitch count varies from row to row, so working increases and decreases that don't interrupt the texture is an extremely interesting technical challenge. I haven't encountered a stitch pattern since where I didn't think, "Well, if I could do refined shaping in blackberry stitch, I can sure do it in this stitch."

Aside #3: I did modify the pattern to eliminate side and sleeve seams. That's just my preference. I do it routinely.

And now for the Jennifer Cardigan, one of Penny's mother Janice Straker's designs:

I bought more of Janice Straker's patterns than I knitted: I love their delicate detail work, so I use them for inspiration, but for the most part they don't fit my sturdy style as well as the other designs. It's nice to be able to dress up in the Jennifer cardigan. However, I usually need sweaters that are a bit more robust.

Like this one, which will get its own full post some day (possibly soon, but you never know):

It's a variant of the Tuckernuck jacket. It's handspun. I'll tell its bigger story later. It's another "need to make up a yarn deficit" one, with some wrinkles.

But for now, a snippet of a digression: in 1986, when I flew from Massachusetts to Colorado to talk with Linda Ligon about whether I might come to work at Interweave Press, the two sweaters I wore were the jackets shown here, Blackberry and Tuckernuck.

The Kickstarter project aims to digitize forty-four Straker patterns, beginning with a first round of fifteen. Although only one of the patterns I want sooner rather than later is in that first round (the Inverness Pullover), I look forward to having access to the full range of Straker designs, especially the Shalor Cardigan, Galway Cardigan, Jim Vest, and Eye of the Partridge Pullover. I've admired a number of the others for years (decades, now) and would be delighted to be able to pick them up easily, as needed.

The thing is this: Even after more than forty-five years of steady knitting, I know I can still learn a lot from Penny Straker's patterns, and that I will have a good time (and produce timeless garments) in the process. I'm really glad I chose good yarns for them. I design a lot of my own garments now, and have for years. One of the reasons that I do so with confidence and a sense of adventure is because of the experiences I had with these patterns.

Go check out that Kickstarter project, if you feel so inclined. If you do decide to support it, make sure you do so at a level that gets you some of the wonderful patterns for your own delight.

January 13, 2013

On the sharpening of pencils

Over the holidays, members of my extended family were discussing real (as opposed to mechanical) pencils. This was in relation to a gift my sister received: a real pencil, and an eraser. It pleased her a great deal. I think there was even a hand-held sharpener included in the package, which was limited to a value of $4. (We performed a holiday-gift experiment this year. It was an amazing success, and we'll do it again.)

The giver of the gift would have provided an artisan-sharpened pencil, except that the still relatively modest cost (in the gift realm) exceeded the constraints put on that part of the present-finding exercise. But the topic of pencil sharpening came up, and we considered for more than a passing moment some aspects of the craft, with which most of us were of an age to have been acquainted in at least an amateur or student's role.

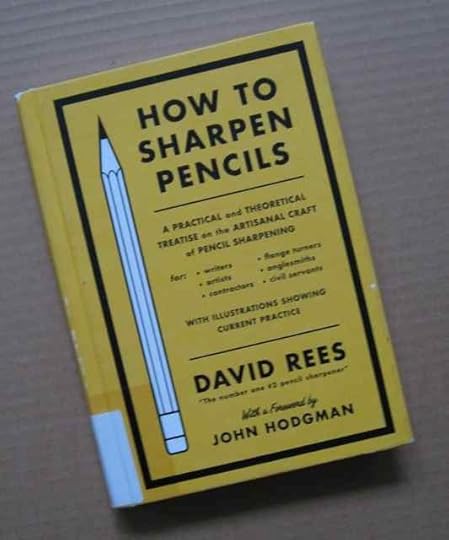

As I was leaving the public library the other day, the following appropriately colored book caught my eye:

So, of course, I had to pick it up.

Here's a brief quote from page 157, with one bracketed comment:

For readers of a certain age [that includes me], the sight (and sounds) of a wall-mounted hand-crank pencil sharpener is as powerfully nostalgic as the odor of tiny milk cartons, the heft of a chalkboard eraser, or the rap of an unforgiving teacher's ruler across the knuckles.

Those happy days, alas, are long gone. . . .

Consider what follows a re-introduction to a set of skills that were likely central to your portfolio in the distant past, but now risk fading into the ledger of the lost arts. Let us turn our contemporary sensibilities to the wall-mounted hand-crank sharpener and rediscover what pleasures remain thereby.

Urban explorers make a habit of carrying a #2 pencil on their person in case they stumble upon a wall-mounted sharpener in one of the decrepit buildings they trespass.

(Hmm. I travel with a spindle, in case of fiber encounters, and a tiny bit of fiber, in case of spinning-tool encounters. How far-fetched is Rees's observation about the carrying of pencils, just in case?)

What was interesting to me in reading this book (and yes, I read the whole thing) was how many of the pencil-sharpening tools and techniques were completely familiar, and the realization that for many people these would be objects as foreign as a spindle, and the associated skills as peculiar-seeming as the making of yarn by hand: knives, single-burr and double-burr hand-crank sharpeners, single-blade pocket sharpeners, and even electric sharpeners (the chapters on these and on mechanical pencils were among the most enlightening). I even learned something: I'd missed the precise application techniques for the multiple-hole, multiple-stage pocket sharpeners, even though they were around and I'd used them often! I also became aware of a number of fine points [sorry . . . or not {grin}] about pencil-sharpening that I considered common knowledge, and I refined [ . . . ] my knowledge in ways that will improve my sharpening technique in the future.

Oddly, the book was a good (if quick) read. The author was previously a political cartoonist, and a census-taker (the precipitating occupation in his career change), both of which occupations explain a lot. The pages contain good, serious information. Note: The book is not suitable reading for most children, due to levels and types of vocabulary. The only chapter I snoozed through was the one on celebrities, but then I don't follow celebrities so I may have missed something that others will appreciate.

Here's an interview author (and pencil sharpener) David Rees did on Portland TV before a book-signing at Powell's. (I wonder: does he sign in pencil??) The prices of pencil-sharpening have increased since the interview aired. An artisanally sharpened pencil would be out of reach of all but the largest of our family's gift-giving categories ($0, $4, $40). If one of us received such a pencil, it would be our Big Gift for the year. (Although with the remaining $5, the giver could also provide a pencil, a sharpener, and an eraser—but, unfortunately, not also the book that provides training in how to use the first two.) It's also true that Rees may actually be making something of a living at his chosen pursuit now.

All this certainly does put my own focus on sheep and wool into perspective. I'm not entirely sure what perspective. I'm working on that.

January 7, 2013

Wool and chocolate: treasures to start a new year

Now here's a splendid way to start a new year.

On the right, treats from Theo Chocolate in Seattle. My daughter and I like to walk to the factory store and pick out a few delights to enjoy after we get home: one per day, split and shared. (The other members of our household don't appreciate chocolate, so we don't give them any.)

The ganache-filled confections have fairly short shelf-lives and you may have to get them on site; there was an "eat by" date on the case that was less than two weeks from when we were standing there choosing (January 9). The chocolate with the white square and stripes is a lemon ganache.

The caramels go a bit longer and can be ordered online. The one with the single swooping line is a gingersnap caramel. That one with the diagonal dusting of reddish sprinkles is a ghost chile caramel. Yum.

Theo is one of very few chocolate producers in North America that roasts its own beans (Hershey's is another; Blommer is a third—the differences in scale between these organizations and Theo is significant). Theo is also the only roaster that is organic and the first to be Fair Trade. Most chocolate manufacturers get their chocolate already processed from the beans--in bulk, ready to melt and form into finished items. (There's a lengthy and fascinating PDF here about the cocoa-to-chocolate process.)

So we came home with our small stash of chocolates—eight, to be savored, one at a time.

And I found waiting for me there a package with a skein of Blacker Yarns' St Kilda laceweight yarn. It made me think immediately of the Theo chocolates: smooth, elegant, tasty, exquisitely prepared.

Let me tell you a little about this yarn, which is a tour-de-force accomplishment that I look forward to savoring as deliberately and carefully as I will the chocolates. Unfortunately, I have no idea how you can get a skein, because I can't locate it on the Blacker Yarns site, but simply knowing it exists shows what can happen when determination, energy, skill, experience, and vision combine.

Okay, I am waxing rhapsodic. There's a reason.

St Kilda is a cluster of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean west of the Scottish Outer Hebrides. No one lives there any more, although evidence of human (and sheep) habitation goes back thousands of years. Two rare breeds of sheep have their home bases on these tiny outcroppings of land, otherwise best known for geology and populations of birds: Soay (from the island of Soay and now also on the larger island of Hirta) and Boreray (from the island of the same name). Their histories are quite different, and I can't go into that much detail or this post will never get done. The association of the breeds with the place is the reason for the yarn's name.

Neither Soay nor Boreray sheep have been bred for consistent wool. Both grow a range of fibers from very fine to remarkably coarse, both within individual fleeces and throughout the flocks.

A couple of years ago, Jane Cooper and Sue Blacker began a project to gather Boreray fleeces from throughout the U.K. and make a commercially spun yarn available, as a very limited run. The goal was to show the shepherds that their wool has value and to show fiber artisans that this breed-specific fiber can be rewarding to work with. Boreray wool doesn't fare well in mixed-wool large-scale commercial operations because of its variability in color and texture. Jane drove all over to get the fleeces—a feat in itself. Then Sue's expertise and the capacities of her mill in Cornwall took over. They produced a wonderful, robust aran-weight yarn.

My concern about the project was that the fine wools that some Boreray sheep produce would be obscured by the blending process. Fortunately, there were a number of identifiable fine-wool Boreray fleeces, and Jane and Sue were aware of this potential issue. They kept aside a selection of the finest Borerays for separate processing.

The result is brilliant. Blacker Yarns blended fine Soay (also a wool that requires sorting at a level that often isn't feasible) with the fine Boreray and spun a delicate yet sturdy yarn that is like a fine ganache: the right flavors in the right proportions, so that each enhances the other, in this case spun to the correct weight and with appropriate amounts of both singles and plying twist.

Handspinners, you can do this—if you have the patience to pull it off. Most fiber mills wouldn't even dream of making a small, specialized run like this. Vision + experience = delicious.

____

Note 1: Apparently one yarn shop in Edinburgh bought the entire small batch of the St Kilda laceweight. There will be a follow-up run, using Shetland along with Soay and Boreray because there currently isn't enough of the latter wools in the right qualities to do a repeat of the first blend. I'm looking forward to seeing that, too—and grateful for the opportunity to enjoy special, short-run yarns now and then, even with the occasional disappointment of not being able to get more. Because who knows what we'll see in a future year?

Note 2: During the holidays, in fact, while I was traveling, someone wrote me through one electronic channel or other to ask if I could teach a workshop at a festival this year. With all the electronic forums out there, I can't remember which one and a lot of digging hasn't revealed the message. The weekend in question isn't an option, because I'm already booked (in fact, it looks like I'm fully booked for 2013 with a couple of commitments in 2014 already), but it would be nice if I could say so directly to the person who asked! If it was you, please get in touch again. Maybe we can consider 2014.

Note 3: I only teach at between four and six events a year. Getting the details squared away for 2013 has been an extended process because of family emergencies (and now I've come down with a post-holiday bug), but we'll soon have details up on the website at www.drobson.info. As a heads-up for this year, however, I will be teaching at the Maryland Sheep & Wool Festival; the Kentucky Sheep & Fiber Festival; and the Wisconsin Sheep & Wool Festival. I'm doing the Explore 4 workshop in Friday Harbor, Washington, in March (full, with a waiting list) and it looks very likely that I'll be doing a similar event on the east coast in the fall.