Deborah Robson's Blog, page 10

October 7, 2012

High Park Fire, 10: Gardening, such as it's been this year

This has not been a great year for gardening.

Our raised beds got built a few years ago. We didn't have the repeated hailstorms pounding the tomato plants into green pulp before they had a chance to get started. There's been a drought, but the water's been applied regularly, if judiciously (none extra for the grass). The squirrels have been far less interested in devouring the vegetables—mostly because of the new reasons that the garden never quite got going with gusto this time around.

(Lady, a visitor, and Ceilidh, a local, very interested in where the squirrel went.)

This has been the year of the High Park Fire, and of resulting guests: Bear (in back) and Lady (in front).

That photo was taken just after they arrived to stay with us in June, when their home burned down. In our back yard it was very hot, although not fire-beset, so they hung out under the deck, where we wetted down the gravel. Later, Bear went to live temporarily with a bunch of livestock for him to protect. Bear is a sweetheart, but he isn't an inside dog (we tried). Lady was scared to come into the house for the first week or two—we could barely get her up the stairs to even look inside, but she's since adjusted.

The house is a bit small for playtime with close to 200 total pounds (90 kg) of dog, but they make do.

Our friends, their dogs, their cat, and their llamas are still living in separate places around the country, most in-state but three critters out-of-state.

I do need to do a fire update.

It's far from over. For those who lost their homes, the process of digging out and determining where, and how, to live next is still in the beginning stages. The fire itself isn't out, although it's 100% contained. During some of our friends' clean-up work this week, which involves removing debris, they saw a plume of smoke very close to where they were working, and discovered a still-hot spot.

Here's Earl's account of what he experienced at their property a couple of days ago:

Way back in June when the wildfires raged through our hills we heard that the danger wouldn't be over until the first snow flew. I didn't take it seriously at the time and was stunned to find smoke coming up from a small pile of rubble uncovered by the clean up crew this week. As I walked up the hill to the barn site I was smelling smoke and wondering if it was just the smell of all the ash that had been pushed into one pile prior to removal. That wasn't the case and as I rounded the corner at the top of the grade I saw a plume of smoke. What ever was smoldering had been under a pile of ash and when that was removed the wind rekindled the hot embers. Three months out and hot spots still remain!

And here are Kris's notes from just two days ago. Samaritan's Purse, which she mentions, is a group of Christian aid-workers that has given them more tangible help than any other organized group, including the government or the Red Cross (or insurance).

As we've been sifting up there, even after Samaritan's Purse, and all the rains, we'd be standing on a pile of soot and have to move, because the underlying soot was still giving off heat. Thankfully, the work boots the kids sent us are heavy enough that we didn't toast our toes. Will be interesting to go up today, see if there was snow there, and where there might still be hot spots—or were. The cleanup crew is amazing. Have already taken over 4K pounds of metal to the recycler. . . .

Toward the end of July, Samaritan's Purse sent a large crew that spent days helping our friends sift through the ashes for anything that might have survived the inferno. Our friends have no connection to this group. Someone who knew about Samaritan's Purse just asked if help was needed, were told "yes" (the timing was perfect: our friends had been estimating it would take many months to even assess the damage), and a large crew was assigned to work "as long as they're needed" to go through the ashes and retrieve any personal belongings that could be salvaged.

Those are only some of the workers on the team. That's Kris and Earl in front, in the (appropriately named) fatigues.

So first there came the "do we have anything left?" part. The next photo comes from early July, when our friends were (1) allowed to go look, because the fire was sufficiently controlled, and (2) able to face seeing what had happened to their home (not easy).

The so-called shabin (the small shed with no utilities that was on the property when they bought it) survived untouched, as did the tractor.

The barn didn't.

That's a steel beam from the barn, along with its roof and a stock gate. Wildfires are both unpredictable and fierce. Note the damage here, and see the building at the upper right in that photo, which is their only neighbor's house, untouched.

Their own house did not survive any better than the barn. Our friends had built it recently, over several years, using all the best fire-resistant techniques and materials. It wasn't quite finished inside. Firefighters who checked their property during the Hewlett Fire (which was nearby not long before the High Park Fire) assured them that their ranch would be easy to defend. The fire took its final run to the north with a speed and intensity that nothing could withstand, and against which defense was impossible.

That's the metal roof of the house, along with melted glass from the windows. Not even the foundation can be salvaged because it was too extensively damaged. Concrete, well-known to be a fire-resistant building material, is not immune to failure when exposed to excessive heat.

Then there's the scraping away and disposal of the debris—very costly, in work, equipment, and dumping fees. Here's some debris that needs to be hauled away and disposed of:

Yes, there's a car in there. The vehicles that our friends saved were the livestock trailer and the truck that hauls it, as well as the small SUV (with a lot of miles on it) which they used to evacuate the small animals and the few personal belongings they could grab. The SUV's removable seat was in the fire, and they've been unable to find a replacement for it, so they now have no method of transportation that can carry more than two people at a time. They have to rent a car when they need to take elderly family members to or from the airport.

Note: Corning ware made it through—just needs cleaning.

The rest of the cookware didn't.

Ditto the washer and dryer.

Yet a pot I had made and given Kris did, albeit re-fired and so not the same colors it used to be. It looks more like raku now.

The Samaritan's Purse folks also retrieved Earl's wedding ring, which he'd taken off while working in the barn. (That's a press release. I'd link to the original news story, except that our paper doesn't make "older" news readily available.)

Our friends are now at the debris-removal stage of the process. They are still living in another set of friends' spare bedroom, with the few things they've gathered to begin replacing their lives stored at our house and in a storage unit. They are still wondering whether, where, and how they might rebuild. (At the end of September, for 259 homes lost in this fire only 20 owners had gotten to the stage of having a permit to rebuild.)

Returning to dogs, Lady has decided that we are okay company, and her safety and well-being is one thing our friends don't have to worry about at all.

Which returns us to the garden. We got some plants in the ground about June 20, which is three weeks after our frost date, but we were busy with all sorts of things.

While both Bear and Lady were with us, it became apparent that it didn't make sense to plant much in our raised beds. (We also didn't waste water on the lawn.) This is what the garden looked like on June 30.

Once Bear moved to a place where he could guard ducks (they're not llamas, but it's a job), we dared to get more plants into one of the beds. (The small bed has a couple of perennial herbs in it. The plan was to plant more. It didn't happen.) The second four-foot bed still was appealing to the remaining visitor. The biggest problem was that the nesting instinct tended to transfer our carefully prepared soil (not the local clay) outside the frame.

We tried putting in an impediment to sleeping in the bed (it's a BED, but still), or at least something to slow down the removal of the dirt. That worked for a few weeks, but I removed it when I discovered it had been knocked over and was posing a risk to the canine members of the household.

Here's 5:50 a.m. two mornings ago, just after the smoke alarm started chirping to tell me that its battery was low and two of the dogs decided they'd like to be outside, thank you (perhaps to see whether the squirrels were awake yet):

And the same morning at 7:20:

Just before the recent frost warning (we iced up last night), we gathered our final harvest of the year. The ripe tomatoes about double our take (from the entire gardening push) for the whole season.

We have a good recipe for a green-tomato curry.

I think most of what we grew in the garden this year, other than a few marigolds that did reasonably well, was a big white dog. Fortunately, she's very nice.

October 4, 2012

Book review: Pure Wool by Sue Blacker

Sue Blacker is wise in the ways of wool, especially with regard to making high-quality yarns from special batches of fleece, including many from rare breeds of sheep that live in the British Isles. She has written us a lovely book that features single-breed yarns, specifically those made at her mill in Cornwall. If you don't know about these yarns, you will want to discover them.

Because I want you to appreciate the unique genius of Sue's Pure Wool: A Guide to Using Single-Breed Yarns, just released, let me begin by telling you about my major quibbles with it. If you are alerted to these at the start, you can get on with the business of enjoying the book's substantial benefits without wondering exactly how many small typos and other bothersome glitches have been allowed to slip through and get into print. The answer to that is: too many. The project would have been greatly improved if the publisher had paid closer attention to copyediting and proofreading. This applies to both the text and the patterns. These matters are important enough that I'd recommend that some ability to independently troubleshoot a pattern be considered a prerequisite for working the designs; that should be sufficient, and they are appealing, so if you have this, go for it. I plan to. The index is also rudimentary. While I generally like the unusual choice of doing color printing on uncoated (not-shiny) paper, in some cases—and this is one of them—crucial images, especially those with dark components (like black fabrics), lose all their detail. A number of finished products are shown for which the source patterns are neither included nor referenced. All these matters are significant; I suggest that you determine not to let them keep you from this book.

So now let's talk about the good stuff, of which there is plenty.

Sue's unique body of knowledge, and what that brings to this book

Sue Blacker began with sheep (Gotlands, which she still has) and then bought a fiber mill, called The Natural Fibre Company. Sue is a wizard at using the mill's equipment to make well-constructed breed-specific yarns, spun either woolen or worsted, available to people who want to experience these fibers without making handspun. Obviously, I'm a spinner. In a way, that makes me even more appreciative of the quality of the yarns produced by The Natural Fibre Company, especially those that are produced under the mill's own label, Blacker Yarns, and are featured in this book. (It's not necessary to have access to or to use Blacker Yarns to get a lot out of the book or its patterns.)

Sue knows a lot about value added: the multiple techniques available to shepherds through which they can increase the financial return they see from their animals' fiber. This is critical to the humans' ability to continue raising the sheep. Whether the value-added chain involves turning the fiber into neatly spun and packaged yarns ready to be worked on crafters' needles or the production of finished objects—blankets, socks, all-natural garden twine, and more*—Sue and The Natural Fibre Company help owners of small flocks in Britain increase their incomes. She also offers consultations to other small mills on how to process challenging fibers into predictable, practical, pleasant yarns.

* Bookmark for the holidays!

For yarn-users, Sue provides a guide to enjoying materials that are not generic (I might add to my description "that are not bland"). She has an intimate understanding of a number of breed-specific wools grown in Britain, of their processing on the small-mill scale (the only way to keep the breed identities distinct), and of how to make good use of the resulting yarns, with their distinctive and sometimes challenging characteristics. (As a bonus, she lightly seasons her comments with her delightfully wry sense of humor.)

Here are some of Sue's observations on spinning single-breed yarns in small commercial batches [my comment in brackets]: "Where a wool is very rare or pretty good as it is [meaning not blended or dyed], we have suggested leaving well alone!" (p. 133) and "As the Wool Qualities and Yarn Types chart . . . shows, soft wools do not necessarily make fine or drapey yarns, and coarse wools do not inevitably have to be consigned to the Aran section. Also a luster wool will be considerably denser than a non-luster, so will make very heavy garments if used as a worsted-spun yarn, in chunky weight, or for larger items. In fact, it is better to use woolen-spun, semi-luster, or non-luster yarns for these" (p. 134).

Her appreciation for the fibers' individuality imbues every page. While other people may make other choices in handling the fibers, of course, Sue offers her experienced opinions firmly and with supporting reasons: "North Ronaldsay makes a soft 4-ply if de-haired of its coarse hairs but loses its character—better to use Shetland" (p. 135). From her viewpoint, based on having processed a more wool than most of us could imagine even seeing in a lifetime, she considers blending, yarn weights, and applications for unusual wools, as well as dyeing for good results on wools that have natural colors to start with.

If you want to be convinced beyond a doubt that Sue knows what she's doing, order sample skeins of a number of the Blacker Yarns offerings and make swatches or fingerless mitts. I've got an ongoing project of doing just that, and it's always a pleasure to pull out a skein spun at The Natural Fibre Company and cast on. One of my favorite discoveries has been the Herdwick, overdyed. Herdwick is one of the least mainstream-familiar yarns to use. In Pure Wool, Herdwick gets equal time with the more familiar, and more pliable, Bluefaced Leicester. Thank you, Sue.

Breeds covered

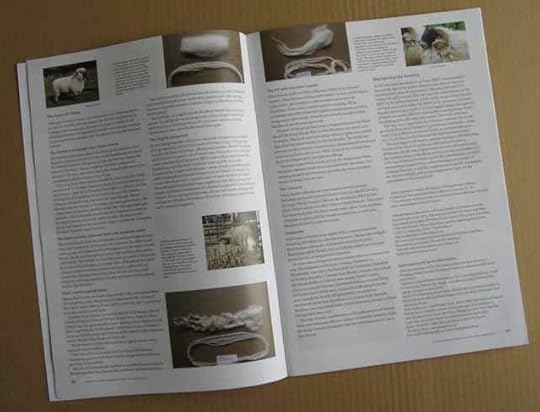

For each breed, there is an introductory segment about the sheep and the wool. The sample shown here is the Hebridean.

These are the breeds in the book, with links to a few of the yarns spun from these breeds that are currently available through Blacker Yarns:

Black Welsh Mountain

Bluefaced Leicester

Castlemilk Moorit

Corriedale/Falklands (explained as a Falkland Islands–sourced wool with a lot of Corriedale in its genetic background)

Cotswold

Galway

Gotland

Hebridean (in blends)

Herdwick

Jacob

Manx Loaghtan

North Ronaldsay

Romney

Ryeland

Shetland

Zwartbles

Patterns

Following the breed information is information on using the wool, including a pattern—or two or three, if small. This is a pattern for a shoulderbag made with the Hebridean wool shown in the previous example:

The designs offer classic-but-interesting approaches to making useful items, with information on why a particular breed's wool was chosen for the project.

In many of the patterns, the introductory description covers variations: changing breeds, combinations of yarns, needle sizes, and structures to individualize the final results. This sort of creative approach to the craft may alarm beginners, but it's how intermediate to advanced knitters think. Any nudging in this direction is all to the good, and beginners will benefit from choosing one of the simpler projects and experimenting with customization.

At least eight photographs are included of items for which instructions are not in the book. The good news is that I've tracked down patterns for most of them (or for patterns that sure look like they'd produce the same or very similar results) by digging around on the Blacker Yarns website. In case other readers find the items shown in these images as appealing as I do, here are the results of my quest:

p. 27: The Bluefaced Leicester vest was made with the Jester Waistcoat pattern.

pp. 34, 60, and 125: The vests made from Castlemilk Moorit, Gotland, and Zwartbles appear to be variations on the V- or Round-neck Sleeveless Slipover/Tunic (vest) pattern.

p. 91: The Manx Loaghtan cardigan is the Chevron Cardigan.

p. 98: I kind of struck out on the North Ronaldsay vests shown on this page (and there is a North Ronaldsay waistcoat, or vest, pattern given in the book, but it's not like the vests on p. 98). Something relatively similar to the vests on p. 98, albeit with fancier patterning, could be made from the Diamond Cluster Fitted Waistcoat pattern.

p. 111: The Ryeland pullover was the first item I went looking for, even though I'd probably draft my own version, and I found it (modeled as sized with a good deal more ease than in the book's photo) in the Cable Panel Unisex Pullover.

p. 117: That Shetland kids' pullover is the Child's Henley Sweater pattern.

It would be very handy to have this information in the book.

For the designs that do appear in the book, the printing choices obscure the detail on photos of the dark-colored items, and the pattern instructions reside in a stylistic realm somewhere between British and North American conventions. Those with moderate familiarity with both systems will do fine. The sizing designations don't conform either to Craft Yarn Council of America standards or to so-called US standard clothing sizing, with at least one tempting garment (the Pucker Cable Tunic, from Galway yarn) having wandered closer to the vanity-oriented catalog sizing realm in which I am a 4 or 6, which is absurd, and makes me wonder what small people wear: size 0000? So ignore the so-called size designations and head straight for the body and finished-garment measurements; that's the only sizing that matters in any pattern, in any case. Some of the schematics don't match the knitting instructions, so either use those with caution or skim past them as well.

The huge strength of the patterns is in the coordination between the qualities of the individual wools and the items designed to be made from them. The comments on how the items were designed are worth reading, even if you never knit any of these things—although I am strongly drawn to:

the Scallop Shell Top by Rita Taylor (Bluefaced Leicester),

that Pucker Cable Tunic by Amanda Crawford (Galway) (the one with the down-skewed size designations),

the Long Cardigan with Hand-Warmer Pockets by Myra Mortlock and Sue Blacker (Gotland, although for such a great winter-jacket design I'd use the optional buttons or a zipper),

the Fall Leaves Beret by Rita Taylor (Gotland, and the photos miss the design's most interesting aspects—which I figured out by reading the pattern, those being the leaf forms at the juncture between the crown and the ribbing),

the Hebridean Handbag by Sue Blacker (guess the breed!),

that Ryeland pullover noted above in the missing-patterns section,

the Ryeland Child's Hooded Jacket by Myra Mortlock and Sue Blacker (another breed-guessing occasion), and

the Climbing Vine Cardigan by Sian Brown (Zwartbles, but there's a much clearer photo of the design, knitted in Jacob, on p. 82).

For me, that's a huge number of patterns having immediate appeal in a single book. And on another pass-through six months from now, I might come up with an entirely different selection. There's a Guernsey pullover by Sue Blacker (Romney) and a color-pattern vest by Sasha Kagan (Shetland) that are already exerting a certain amount of pull.

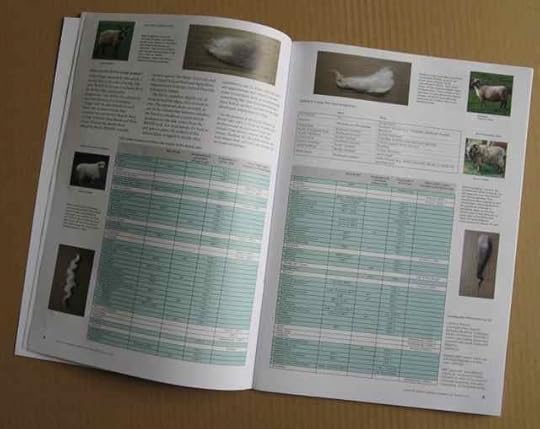

Supplementary sections

The front and the back of the book contain general information, called "Pure Wool Basics" in the front and "Pure Wool Practicals" in the back. The information in the back is meatier, giving insight into the breeds covered from different angles and incorporating three charts that consider wool characteristics and qualities from the small-mill perspective, and a visual representation of suggested substitutions between breeds for the patterns in the book. The dark red indicates the breed suggested in the book; other breeds Sue considers as appropriate substitutions get progressively lighter with their decreasing suitability.

There's also a chart on natural colors along with general thoughts about dyeing these fibers. It does not include information on using any specific types of dyes, but the overview and way of thinking about dyeing apply to any type of supplementary coloring.

The "Wool terminology" and "Yarn terminology" (front of book) and "Knitting know-how" (back of book) sections appear to have been put together quickly and could have been made more useful with appropriate editorial guidance.

In sum

There's a tremendous amount of unusual and intriguing information in Pure Wool. If you like breed-specific fibers and yarns, it will be a fine addition to your library, despite the shortfalls in the editorial processing and production. Although I was provided with a review copy of the book by the publisher at the author's request, that obviously has not influenced (and never would affect) what I have to say. I would have happily purchased a personal copy—and would have paid significantly more than the US$19.95 cover price for a book that had been edited more thoroughly.

There is excellent material here. I would have liked to have seen it fully honored in its presentation.

Forewarned, do seek out Pure Wool for all that it does provide.

September 28, 2012

3Ls, 3Cs, and a Cormo sweater

Last weekend I was at The Spinning Loft in Michigan teaching a two-day workshop called 3Ls and 3Cs. With such a cryptic title (although yes, there was a description of the class), I was delighted to find a room filled to capacity with wonderful folks. We couldn't have fit in one more. Fortunately, everybody had a comfortable spot to work (once we fiddled with the positioning of a table and a couple of wheels).

This is half the room before we got started on messing it up:

And this is looking in the other direction:

I didn't get a picture of what the space looked like two days later. It was impressive.

The top photo shows a pretty good view of one of the THREE walls of wool Beth Smith has displayed for sale in the shop. She's in the process of reorganizing her business so she can do more teaching and writing, which means she's closing the retail location, focusing her sales on wool and some selected equipment, and moving the collection of fleeces to a workspace at her home. The website will be the way to find her and her treasure trove.

This was a new workshop for me. It could have been two one-day workshops, instead of a two-day, although the material became a whole lot richer because I could relate the two experiences to each other. When Beth and I decided that I'd do another class for her, we both thought, "Let's do something different." We came up with the concept and the description, both of which remained true throughout the preparation and teaching phases. Yet between the two, when I was researching the material I would present, I made so many new discoveries about sheep and wool and the history and practice of using these resources that it was like I'd unintentionally opened a door into yet another room full of fiber-y magic.

The concept:

3Ls: The three Leicester breeds, which have confusing names and quite different wools: Leicester Longwool, Border Leicester, and Bluefaced Leicester.

3Cs: Two C breeds that I couldn't tell apart before I began work on The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, Corriedale and Cormo (they're EASY to distinguish now, of course), plus another C that I knew would offer a totally distinctive spinning experience and that came from the same part of the world, Coopworth.

So we had three British breeds and three from New Zealand and Australia. We had six wools that vary in texture, history, interrelationships, and behavior.

I knew we'd come up with a good idea for a workshop, but I didn't realize exactly how good it was.

When I was getting ready for the class and dug into the details of these breeds (more deeply than we could for Fleece & Fiber), I came across details pertaining to each that opened my eyes to new ideas, as well as relationships that I didn't know existed between them, and so we ended up looking at about how breeds come into being and are defined, how some of them move around the world, why some succeed wildly while others (equally valuable) become endangered, how to tell one type of sheep from another (although it's hard to be certain, especially with all the crossbreds out there, a set of clues can help narrow the field) and the same about wools. We touched on how people worked with genetics before Mendel and Darwin came along, and some ways in which they work with them now.

And we spun a lot of delightful wool while surrounded by adventurous and interesting companions.

Thanks to all the folks who came to Howell, Michigan, for this voyage of discovery!

______

Then there's the sweater. In my so-called spare time, I'm making both swatches and a few finished objects that show possible applications of breed-specific wools. Recently finished, and debuted at The Spinning Loft as a working part of my wardrobe, was my new Cormo sweater.

I completed it while I was in Seattle helping get Mom settled in her new living situation. That's where I took the photo above, my first experiment with the self-timer on my camera. (My sister's house is set up better for this type of activity than my house is: she's got a great dividing wall between the kitchen and the dining room which can be used for an appropriate-height camera support. Plus she doesn't have boxes of wool samples in the background everywhere.)

It's Elsawool Cormo, fingering weight, woolen spun, in medium gray and dark gray. The pattern is Ann McCauley's Corrina, from Jared Flood's publication Wool People 3.

I made a few modifications in the design. Ann likes to work her sweaters in pieces, while I like mine in the round, so shifting construction methods was number one. Ann's design is single-color, and I had two colors that I wanted to use; the question was how, and you see my solution. I didn't figure I needed to draw a dark horizontal line across my hips, so the lower lace section is in the main color. I also have quite narrow shoulders that benefit from enhancement, so I added saddle shoulders. The biggest trick in that modification was calculating the saddle construction so they didn't bump into the lace patterning at the center front. (There is also a small lace motif at the center back, but its positioning wasn't an issue for this modification. I could have worked the lace and the saddle shaping simultaneously, but I didn't want to.) The other thing I needed to determine was how to combine the color shifts for the motifs at center front and back (intarsia) with the lace patterning—that is, where to change colors. I made my joins one stitch outside the lace areas, so that the lace-producing maneuvers would be cleanly inside the dark sections.

Oh, and I lengthened the body and the sleeves, but I always do that. I'm long-waisted, and I also like to have sleeves that keep my wrists, and ideally part of my hands, warm.

The sweater is extremely comfortable and practical. I ended up wearing it all last weekend, because the zipper on my sweatshirt broke on the first evening and limited my weather-appropriate wardrobe options. Not a problem. This sweater is a delight.

Cormo: Soft enough to be worn next to the skin (like in camisoles or sweaters to be worn without an underlying shirt); woolen-spun for lightness and warmth; fingering weight for flexibility and versatility; great color for travel; and it's wool, so when I spilled tea on myself I just grabbed a kleenex and dabbed it off, with no damage done, even temporarily.

I could live in this sweater. I may need another one . . . from a different breed-specific wool. I'll have to contemplate which breed, and gather or make the yarn. I also need a cardigan.

_____

At the end of the weekend, Beth and I got to go see sheep! (This is a Scottish Blackface.)

September 14, 2012

Researching sheep (still), and miscellaneous semi-related comments

When Carol Ekarius and I wrote The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, my responsibility focused on the fibers and hers on the animals. While I got into research and writing on some of the species and breeds where I'd already done a lot of digging and thinking (notably Soay, Boreray, and unsnarling a few of the Cheviots right at deadline), for the most part she handled breed definitions and history. We both worked to our strengths and backgrounds. It was an excellent division of labor.

Now that I'm teaching, and don't have the book deadlines pushing me so hard, I'm building into my life opportunities to study additional breed history to increase my understanding of how the fibers we have to work with have been, and are, influenced by social, political, economic, and geographic forces.

At the end of next week, I'm teaching a new two-day workshop at The Spinning Loft, in Howell, Michigan. It's called Three Ls and Three Cs: Two Clusters for Spinners’ Delight and Edification.

Each day will focus on three breeds that are related historically and very different to spin.

The "three Ls" include Leicester Longwool, Border Leicester, and Bluefaced Leicester. These three breeds from the British Isles all have lustrous longwool fleeces that differ from each other in enchanting ways, and examining them will give us an opportunity to look at the shifts that came with early understandings of genetics, along with changes induced by human population growth.

The "three Cs" are Corriedale, Cormo, and Coopworth. These three come from the Pacific nations of New Zealand and Australia. They link to the classic European breeds but take them to different places in the fiber spectrum, again pushed by social and economic forces that are related to, but not at all the same as, those that produced the British wools we have today.

Every time I research a breed, I make amazing discoveries that apply directly to my fiber work and that also compel me to read and think more.

What I'm trying to figure out now is how (other than workshops and classes, because I can only do a few of those each year) to present the material I'm coming up with—and wondering whether (and how many) other fiber folk may be interested in examining the topics at this depth. I know some are. I don't know how they might want to access the information. In the "old days," I would have written another book (although I'm not sure it would ever have gotten finished). In these "new" days, it's tempting in many ways to throw it out on the internet for free, although I have no idea how I could afford to pay the bills if I did that. (I'm not willing to put ads on my blog or elsewhere).

At the moment, I don't need to solve those problems. At the moment, I have a workshop to teach next week and will be able to spend time with people with whom I can share these insights I'm mining and collecting out of a variety of sources. I'm pulling together disparate bits of information with the help of graph paper, pondering, and some computer programs. (Right now, I'm using Illustrator to make timelines and breeding charts and other graphics that pull together what I'm seeing in ways that I can present to others. I've been dipping into Tinderbox for collecting and organizing thoughts while they're still at the "scrap" level. I need to learn to use DevonThink, into which I have been throwing resources for a while but from which I haven't figured out how to retrieve stuff. I need a few months just to learn the basics of the software that I now need to use because the scope of my work has exceeded the previous systems.)

This morning, I spoke with Carol at The Spinning Loft (another Carol) about the wools we'll have to play with while we talk about how the breeds came into being. We'll have in our hands the tangible evidence that goes with the history. It doesn't get better than that.

_________

Meanwhile.

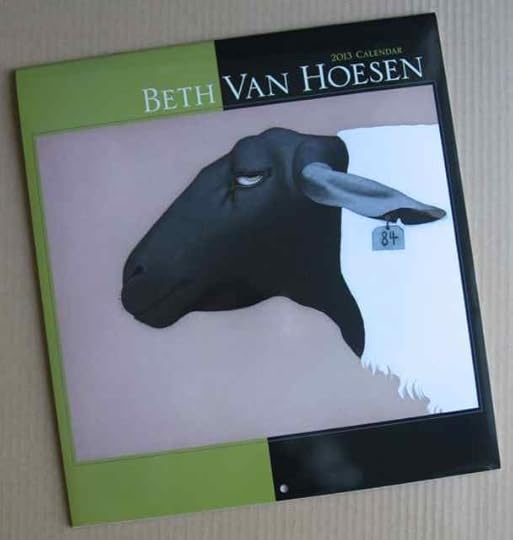

I bought one of my calendars for next year. I happened across it at the Tattered Cover on a visit a couple of weeks ago, thought about it at length, and purchased it at the Colfax store on Wednesday when I needed to be in Denver again. I was glad to find that a copy had waited for me to return.

It's not a sheep calendar. The only sheep image is this one Suffolk. I looked across the internet for the possibility of getting a print of this piece, and while they exist they're nowhere near affordable for me. Artist Beth Van Hoesen is unfortunately no longer with us, although from her 84 years she left a splendid legacy. I'm captivated by her sense of graphic design as well as her ability to dance between the unique and the universal.

The other images in the calendar also appeal to me, but yes, the Suffolk hooked me. People talk about sheep as stupid. They are not. The relationships between humans and animals are complex, and far from one-sided. Beth Van Hoesen captured that here, and the other art selected for this calendar speaks to the conditions of some other inhabitants of our world. It is, as a whole, a celebration of individuality and diversity.

I can live with that on a daily basis for 2013.

______

Speaking of 2013, my teaching calendar is penciled in. Because of my mother's stroke, I haven't had time to finalize the arrangements for several events and I need to get on that soon. One of the things that's in the works for late 2013 or some time in 2014 is another trip to the British Isles, for both research and some teaching.

______

Unexpected postal delivery:

To whoever sent me this surprise package from The Loopy Ewe, thank you! I have not been able to determine, and the elves won't reveal, the source.

Very sweet. A special set of coordinating colors dyed by Lorna's Laces. Something fun and lovely will come of this.

_____

But not until I finish prepping for next week. Well, I could probably wind the yarn into balls. . . .

_____

Note: Because I got 25 spam comments in one day this week, I've notched up the requirements for commenting on this blog. I'm trying to keep them at the minimum reasonable level.

September 7, 2012

Unexpected yarn shop: Warehouse Woolery, Chelan, Washington

You never know where you'll find a great yarn shop.

I was recently visiting family in Washington and a bunch of us spent some time together near Lake Chelan in the eastern part of the state. What I discovered there was the Warehouse Woolery. By address and identity "in" Chelan, the shop is actually located a few miles outside the town, toward Chelan Falls, in an old apple warehouse closer to the Columbia River than the lake. I drove by the signs several times as the family went about its activities, and on one of our outings I managed a snapshot from the passenger's side of the car.

Another thing I managed to snap (although it was hard) was the charming collection of goat sculptures at the intersection of highways 97 and 97A, between the main part of Chelan and the Warehouse Woolery.

There's no place to slow down or reasonably pull over and get a good shot of the collection. I did manage one photo while I was a passenger, and another while at a stop sign on a day when there was no traffic in any direction.

It by Jerry McKellar, although they are not stylistically like his other work. I love the way the flat planes of the metal pieces have been combined to produce such a sense of movement. They are far nicer in reality than I am able to hint at with these drive-by images. I think there are five goats in all, although I'm not sure because I only captured four with the camera.

Only on my way out of town at the end of the visit was I able to visit the Warehouse Woolery, which ended up being warmly welcoming in a bleak stretch of industrial landscape.

The Warehouse has a lovely and diverse selection of yarns. One of the means I use to evaluate a shop is its selection of knitting needles, and this spot passed my most stringent tests. They didn't have a lot of different needles, but were well stocked with some of my favorites (Addi lace; instead of getting the longer double-points I needed for the project-in-progress, which they also had, I got two 24-inch Addi lace needles in the appropriate size—far more versatile in the long run).

The pile of books by the sit-and-knit chairs and couches told me immediately that the buyers of stock for this store are imaginative in their selection of titles to carry:

That's Annie Modesitt's independently published Cheaper than Therapy anthology on top. I did not rearrange the books. The relatively small number of titles on the bookshelves showed similarly nuanced selection criteria.

Of course, the yarn that interested me most showed up in the back room. Did not have any identifying information. Was not priced. I picked up one skein of the creamy heavier weight and one of the moorit (light brown) fingering weight, walked to the front counter, and asked, "What can you tell me about this yarn?" The answer, correct but not quite what I had in mind, was, "It's wool."

(It was in skeins, not balls. These are the two units I brought home: the fingering weight.)

The ensuing discussion, following my "Tell me more . . . " and a suggestion that I really did want a lot of detail, was MUCH more interesting than the initial response.

As it turns out, the wool had been very well spun by a small-scale mill (no longer operating) from the fleece of a sheep named Roo, who was part of a flock that one of the shop's owners used to have (before the shop began to compete for her shepherding time). Roo's father was a Merino/Rambouillet cross (and moorit-colored) while Roo's mother was a full Rambouillet, making Roo 100% fine-wool, consisting of 25% Merino/75% Rambouillet. Delightful fleece, made into a "this is your reliable, soft and yet durable, security blanket" yarn. I rationalized that some day I'll be able to take time to knit something that is not exclusively breed-specific as a demo for teaching (either a swatch or an actual item) . . . or that Merino/Rambouillet is close enough to breed-specific to count. Whatever. I couldn't leave these skeins there. I wanted to take the entire quantity of both types of yarn, because it wanted to come home with me, but my current accounts of both bank and energy argued against that option.

Two is good.

It is, indeed, a very nice yarn shop in an unexpected location. If you visit, be sure to look thoroughly at the high-quality yarns in the front room, but also check out the corners in the back room. And ask questions. You'll end up in an interesting discussion, and just possibly with some unique yarn that comes with a story.

August 29, 2012

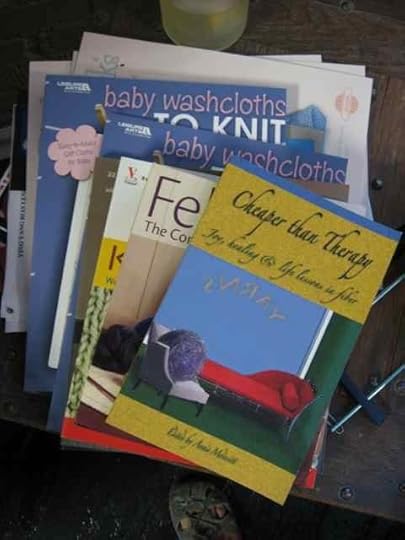

The Journal for Weavers, Spinners & Dyers - Wool Issue

I'm way behind on blog posts. I love writing them, but have been traveling both for work and for family, and have jotted down notes upon notes that have not turned into the reality of new posts.

Here's a quick item, though.

I arrived home from the airport (again) at midnight last night to find the Autumn 2012 issue of The Journal for Weavers, Spinners and Dyers, which is a special wool issue celebrating The Campaign for Wool.

My daughter, who ordinarily does sort my mail while I'm gone but never opens it without checking with me first, confessed that in this instance she couldn't stand the suspense of waiting until I returned from this latest trip to see what had come of the endeavor she'd watched take shape over more than a year. She had opened the plastic wrapper and taken a look. The issue contains an article that I was intrepid enough to undertake writing, called "Tracing the British Sheep Breeds."

There's a story behind this, of course.

More than a year ago, spinning editor Christina Chisholm contacted me and asked if I could write an article for an upcoming special issue on wool, the subject to be "the history and development of British sheep breeds"—as I mentioned in my reply, a "vast topic." Christina indicated that they were looking for "a central lynch-pin educational feature to the whole special focus issue, which will mean that a huge amount of information will have to be condensed. . . ."

Now here's the problem. I knew right up front that this would be a nearly impossible task. Even (perhaps especially) because I had The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook and the Interweave DVD set on spinning rare-breed wools behind me (the reasons Christina had contacted me), I wondered why I'd been chosen for this assignment and whether I really would have the temerity to say yes.

While I have a reasonable amount of common sense in my daily life, I seem to have almost none in determining what jobs I consider too intriguing to decline. I looked at the generous deadline—it was merely July 2011 and they would not need the article until March or April 2012—and considered that I might be able to move forward at a pace that would make it possible to pull off the challenge. I really wanted to dig into "the history and development of British sheep breeds" and see what kind of sense I could make of them. I would simply have to accept that I'd need to do so in a good deal less space than has been devoted to the task by wiser heads before me. The allowable space was 3,000 words (an increase over the journal's regular 2,000-word maximum for a feature).

Well, I was right. It wasn't easy. At the same time, it continued to be irresistible. I had to begin with "what ARE the British sheep breeds?" (a question that led to the chart in the middle photo above) and go from there. This research and writing pursuit is part of why my blog posts were few and far between over the fall, winter, and spring than they might otherwise have been (then, of course, I also need to make a living, so it was time to start traveling to teach workshops, with some family adventures thrown into the mix).

By April 14, I sent Christina a progress report: "Yes, indeed, I've been working on that article. The BIG problem is that it's an impossible topic, although of course I'm not letting that stop me. I keep wrestling with it, and it keeps growing more arms and legs and throwing me to the ground. I get up again and go back at it." I got a bare-bones version of 6,000 words written, and then went to the mountains for two days of concentration, during which I cinched it down to the requisite 3,000 words, which I transmitted by April 24—at which point we began to work on photos. Over the next two months, we worked out the details.

The result is not definitive, but it's a snapshot of how to approach the basic questions about the history and development of British sheep breeds, and some observations that I came to while diving into those questions.

I just read the piece in print for the first time, and while I think a lot (all?) of the statements would benefit from more depth and elaboration, I think it has value as an overview and that, ultimately, it works.

If you're a sheep-and-wool enthusiast, you might want to check out issue 243 of the journal. If you do, let me know what you think. The publication contains a lot of other interesting articles, including one by Margaret Russell and another by Elizabeth Lovick—and much more. The short news blurbs contribute useful information and links. Also, if you think you might be traveling in the British Isles, Isabella Whitworth has been brave enough to assemble a list of woolly sites and events that can be downloaded from the journal's site until August 2013.

(By the way, those are Ryeland lambs on the front cover.)

July 6, 2012

Waltz for the Wolves

Last Saturday night was the Waltz for the Wolves, the annual major fundraiser for W.O.L.F. Sanctuary, a rescue and education organization working with wolves and wolf-dogs, which recently has been hit by the High Park Fire, although all the wolves were—over a number of days and by a number of means—relocated to appropriate alternative locations outside the fire area. (I hesitated over adding the word "local" on that description of the fundraiser, but left it off because people attend from quite far away.)

Here's the room where the Waltz was held; I'd guess there were between 300 and 400 people there.

The slide show primarily documented the relocation process. The wolves normally live in large, customized habitats, a number of which now contain specially constructed fire dens—recent additions that likely made a big difference in the survival of the less socialized wolves who had to be evacuated later, rather than sooner.

The balloons were part of a raffle for special, donated prizes, one of which will appear later in this post.

Here's this year's program for the event, with the special bookmark featuring Whisper:

Some of the wolves and wolf-dogs serve as ambassadors, because they are able to handle, more comfortably than the others, (1) travel by van, (2) being around people, especially ones they don't know, and (3) unexpected events. These animals are key to the sanctuary's educational programs. I have always seen them taken out together (that is, at least two wolves in each adventure), and their needs always come first. The two ambassadors at the Waltz were Pax and Sasha, who are habitat-mates.

At this year's Waltz, the main room was quite noisy, so Pax and Sasha came inside and looked around (meaning cruised the WHOLE perimeter of the space, quickly), went outside and got quiet again, then got curious and asked to go back inside for another speedy tour, part of which was captured above. They were on site for about an hour, then taken back to their temporary residence while the humans continued to do their thing. If you have access to Facebook, there are much better photos of Pax and Sasha on the W.O.L.F. page there.

Tunyan and Sigmund are also, as two pictures from 2010 show, quite social, but they aren't ambassadors. Among other reasons, Siggi doesn't like the car-transport part of the equation and Tunyan is a sneak-thief with a special interest in cameras.

Here's Sigmund with Kris Paige, who introduced me to the sanctuary and has spun and knitted items of wolf fur for the Waltz for the Wolves auctions for the past several years. Like many of the others, Sigmund is a wolf-dog, with too much wolf in him to be a good household pet. Tunyan is coming up behind Siggi to see whether she can steal my camera.

She didn't get it that time. (Tunyan is Lakota for "brat.")

These are some of the wolves whose fur I spun for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, thanks to Kris's introduction.

One of the reasons that I am fascinated by and interested in the W.O.L.F. Sanctuary is its strong, clear advocacy and its blend of empirical and intuitive guidance. When faced with thorny questions, they consult various people beyond their immediate boundaries, including bioethicist Bernie Rollin, and they pay a great deal of attention to the wolves themselves: what their behavior indicates about what they need. Also because we know Michelle Proulx, who began as a basic-level volunteer (when she was working at the same bookstore that my daughter did) and is now the educational program director for the sanctuary, in addition to being a brilliant animal caretaker.

Michelle is a reason that one of the program items at the Waltz is belly-dancing, because that's another thing that she does. So we enjoyed the proficiency and variety of the Rocky Mountain Belly Dance Company.

This year, Michelle didn't dance with the troupe because, with the fire, she had too many other things she was responsible for. This year her fellow dancers told her enough.

The Stone People Drummers played for the dancers and also by themselves.

The belly-dancers even, later in the evening, got a lot of people up dancing with them because of this kind of energy.

The live auction included some of the items made by Kris, who had been working on them both before and during the time when she was evacuated from her home. The GREAT auctioneer for the live auction was Debbie Stafford (for an interesting time, read her bio!), who I gathered is the sister of the sanctuary's clinical director, Priscilla Dressen. She did an amazing job.

Back to those gold balloons. They had ticket numbers on them, and could be purchased for a reasonable sum for a chance to win one of the raffle items. By means of her gold balloon, Kris won a custom skateboard with an image of Shaman, a wolf who has been important to her, as well as to a number of other people involved with W. O.L.F.  Kris looks whomped here because she and her husband Earl lost their house and barn to the fire just a week earlier, and she'd recently seen photos of what was left, although she hadn't been to the site yet—pictures of that are forthcoming. We had to egg her on to go to the Waltz, which is a lot to take in for humans as well as wolves—but a number of us, all over the country, thought it was really important for Kris to be there, even though we knew it would be hard. It was hard. It was also worth it: Shaman said so.

Kris looks whomped here because she and her husband Earl lost their house and barn to the fire just a week earlier, and she'd recently seen photos of what was left, although she hadn't been to the site yet—pictures of that are forthcoming. We had to egg her on to go to the Waltz, which is a lot to take in for humans as well as wolves—but a number of us, all over the country, thought it was really important for Kris to be there, even though we knew it would be hard. It was hard. It was also worth it: Shaman said so.

Shaman, who has now (as the sanctuary phrases it) returned to spirit, is a perfect guide for the Paiges' rebuilding effort. Two people came over with offers to buy this item from Kris, but we all agreed that it was the perfect thing for her to have as a cornerstone for bringing into existence what will be the Paiges' new home. Shaman was, for a long-time, one of W.O.L.F.'s primary ambassadors, and he's still doing good work.

Here's one of the items Kris donated to the fundraiser—fingerless mitts from Sigmund's fur:

And another, a hat from the signature wolf for this year's Waltz, Whisper:

In all, Kris made two hats, two pairs of fingerless mitts, and a six-foot-or-so scarf, all from either Whisper's or Siggi's fur this year.

Kris is doing much better now. It's one step at a time, and Saturday night was a big and important leap. Thanks to everyone who has sent messages and/or help through the website I mentioned in a previous post. Kris keeps saying things like, "There's someone here who says they came from your blog!" and "Scotland?!" The support, both emotional and practical, is priceless.

Here's another photo of Kris from our visit to the sanctuary in 2010. In this one she's with Rajan, who is a sometimes ambassador (in a pinch, though I hear he'd rather stay home). I think he'd just been nibbling on Kris's hair.

Photos by Judy Fort Brenneman (at the Waltz, because I forgot my camera) and by me and Kris Paige (at the sanctuary).

The wolves have all returned home to their sanctuary habitats now, with much relief all around. W.O.L.F.'s major advance fire planning has paid off—combined with a bit of luck that the fire, when it reached the sanctuary site, was not burning more fiercely than it was. Several small buildings were lost, but the main buildings and most of the habitat—and the fire dens! which worked!—came through.

July 5, 2012

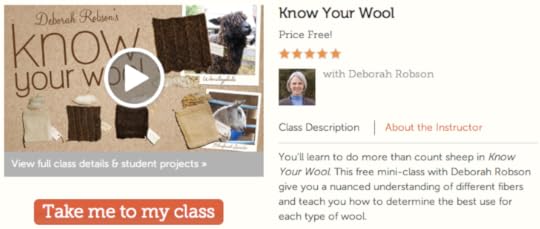

Craftsy online class: Know Your Wool

A while back, Liz Gipson, who was an assistant editor of Spin-Off after my years at Interweave Press, asked if I'd consider presenting an online class through a new outfit called Craftsy.com. Because I know and like Liz, I said okay, not really knowing what I was getting myself into.

It turned out to be enjoyable and, I think, really useful, even though it involved having me make it look like I was calm and coherent in front of a camera (not one of an introvert's usual top skills). The fact that Liz was the producer and the studio folks were fantastic helped a lot.

The course was released a couple of days ago: it's called "Know Your Wool." I love that it's free—Craftsy offers free courses as a way to introduce people to the platform, which is unique, innovative, and very interesting. There are videos, downloadable materials, and easy ways to take notes, ask questions, and have discussions. In the case of the free courses, the instructors aren't required to participate in the discussions, although I've been doing that and will continue to check in from time to time, as my schedule permits.

Here's the introductory screen for people who have already signed up:

As the instructor, I'm considered already signed up {wry grin}.

If you decide to check it out, let me know what you think. The lessons are between about 10 and about 20 minutes long. Even when I got the alert that I needed to proofread the onscreen type within twenty-four hours (with several other imminent deadlines), I was able to fit the viewing into odd moments during the day and get done in time.

Also, if there are other things you'd like me to teach in an online format, let me know. I had a great time and am contemplating what to do next.

As time permits, I'll be giving the back story here on the several pieces that I made to demonstrate the concepts that I talked about in the lessons. They include the Suffolk sweater, the Merino cowl, the Bluefaced Leicester socks, and the Wensleydale socks that weren't completely finished when we were in the studio preparing the course but as of yesterday only need to be washed and blocked.

Craftsy on Twitter is @beCraftsy.

On Facebook, they've got pages at craftsy, FiberArtsClub, and KnittingClub.

On YouTube: beCraftsy.

High Park Fire, 9, relocating dogs

Our friends Kris and Earl Paige have eleven llamas, four livestock guardian dogs, and two cats (one still missing, and we are hoping she found a safe place during the fire: it's possible). Since their house and barn burned down, the Paiges need a place to live, but first the animals need to be settled.

The llamas have been in a first set of temporary digs (two locations, one for the males and one for the females). They are in the process of being moved to a second set of temporary, but more long-term, housing, since it's obvious now that rebuilding will have to occur before they can go home.

Two dogs, Bear and Lady, have been with us, while the other two, Hoss and Heather (siblings), have been boarded at a vet clinic. Just before July 4, Bear was moved over with Hoss and Heather because, while he will protect his llamas from mountain lions, coyotes, and bears, he's afraid of thunder, lightning, and other things that go boom. We have been having daily bouts of thunder and lightning (without much rain), and even with a fireworks ban, we didn't trust folks not to explode things around here. (For the most part, they haven't. But a small handful of people did ignore the prohibition.)

Hoss, Heather, and Bear now need to be transported to North Carolina to be cared for and to have work to do while demolition and reconstruction happen on the home front. They will be with the friend of the Paiges who introduced them to livestock-dog rescue. The trick is getting the dogs there.

Obviously, with the heat and distance involved the transport vehicle will need to be air-conditioned in the cargo area as well as the passenger area. Unfortunately, it appears that auto rental agencies don't do one-way rentals on cargo vans. What's needed is probably an air-conditioned panel van. The driver who is available and familiar to the dogs has a regular, rather than commercial, driver's license. We're working on finding interior measurements of regular vans to see whether big-dog crates will fit. That information is not readily available online (we keep finding cargo-area width measurements but not length measurements).

Putting this together is like building a house of cards and hoping it doesn't fall over.

All of the dogs were rescues and all have been given appropriate work to do with the Paiges. Directly after the fire, Kris thought she was going to have to turn three of the four over again to guardian-dog rescue for rehoming, until the friend stepped in with the North Carolina solution (offer of housing, as well as support for the expenses of transporting the dogs)—a great relief all around, even if the logistics are complicated.

Bear is a true sweetheart as long as you don't threaten his family, four-legged or two-legged. He's not a house dog or he'd be in our house.

We've done our best to keep him entertained, mostly with frozen peanut-butter-filled bones. When bored or anxious, he tends to go through fences. We thought ours was sturdy. He's determined. It's been reinforced several times during his visit.

We were really sorry to see Bear go to board elsewhere, but we couldn't protect him adequately from the daily weather rumblings and he was so happy to be allowed to share a run with Heather! He was also lonely here, despite our best efforts. We even took our work to the back yard and sat with him to keep him company, but he needs a job to do.

These are Heather and Hoss, in what Kris describes as "an unusual calm moment." Someone in California intentionally crossed Akbash and Irish Wolfhound (I think I have the breeds right) and then, when the pups were ten months old, became alarmed at how large they were getting (this was a surprise?) and wanted to get rid of them.

They're statuesque, and LIVELY. We didn't even consider trying to keep them entertained at our house.

This is Heather:

That's a corner of the house in the background. Kris and Earl were on the property yesterday and in another post I'll share some photos of what is left there. Throughout evacuation and all the other phases of this process, getting the animals settled has come first. Then the people. Then the buildings and property can be dealt with.

And this is Hoss, up on a hay bale, looking for trouble:

His paws are HUGE. So's his nose. Kris says of that photo, "Hoss, standing on the TOP of the hay, woofing down (from about 8 feet up) at me walking into the barn . . . it's his favorite trick."

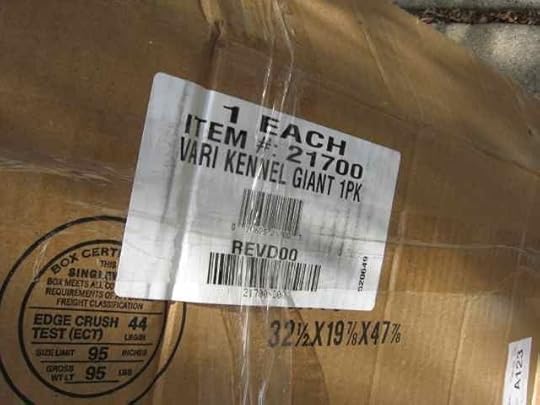

This morning, FedEx delivered to our house three GIANT dog crates for the transport of Bear, Heather, and Hoss.

Those boxes weigh more than 50 pounds (23 kg) each. I had to hip-shove them out of the way so we could get our bikes in and out of the garage.

Lady understands how to behave in a house, so she will be staying in Colorado during the regrouping time. She can walk on a leash, and do other tricks. She's not as good a livestock guardian as the others, but she's very protective of "her" people.

We now count in that number of honored folks.

It took a number of days before Lady was willing to come in the house, even when Kris was staying with us. (She and Earl are now with friends who have more space than we do.) Then it took a while longer before she decided she could go on walks with us. Now she's in the house most of the time, and walks with Ceilidh (the Border collie rescue) and Tussah (the red-dog rescue) twice a day.

Which is pretty darn nice.

I'll be glad when all the transport pieces are in place and Bear, Heather, and Hoss can be past this phase of the dislocation. This morning, we measured big dogs for harnesses to be used during travel, and those are being ordered. Food has been ordered for them (four big bags of dog food burned up). The crates have arrived. Now all that's needed is a vehicle that will hold three big crates and is air conditioned.

One step at a time.

Kris and Lady

(The photos are a combination of mine and Kris Paige's.)

June 29, 2012

High Park Fire, 8: Sunflower Ridge Ranch

I err on the side of caution about privacy, so have not revealed a lot about what my friends who lost their home have gone through recently, other than mentioning the dogs and some other details. There is now a website created by their adult kids to help them recover from the loss of their ranch to the High Park Fire.

My friends are Kris and Earl Paige. While moving around the country for Earl's job, from which he recently retired to the ranch, Kris has been extremely active in rescue efforts involving llamas and livestock guardian dogs. She's put a lot of miles on getting animals out of bad situations, and is an avid supporter of the WOLF Sanctuary; she's been spending time during evacuation spinning and knitting items, made from Whisper's and Sigmund's fur, for the silent auction happening tomorrow night at the Waltz for the Wolves. If that wasn't enough, she recently completed the rigorous vet tech program at Front Range Community College.

Their property is Sunflower Ridge Ranch, and it took them many years to put it together. On June 22, the High Park Fire jumped the Poudre River (with more than a spot fire: a blast across the river) and ran 7 miles in 5 hours. That was the event that incinerated the ranch buildings.

This is what the ranch looked like before the fire.

This is what it looked like yesterday.

When we hear that fire evacuations have been lifted, or when another event catches our attention, we tend to think it's all over and everything goes back to normal. It doesn't.

Their llamas are in two different locations, and have had to be moved not only out of the fire area but since then. Their dogs are being temporarily moved across the country, and Kris and Earl are hunting for a place to live while they start over at the ranch.

In some ways, perhaps what grows from the ashes will be better. Sunflower Ridge Ranch was built entirely off the grid, and the solar system, while it worked well enough, was somewhat problematic. I hope the new solar system goes in without those complications. It's a small thing to wish for, but it would be nice. And more little nice things like that would be super.

Meanwhile, the people who have lost their homes are taking one issue and one minute at a time: Are the dogs okay now? Are the llamas okay now? Do we have a place to sleep tonight? Even with abundant friends, these questions rise, and they rise repeatedly for all the people affected.

There are, at latest count, 259 other stories of homes lost to this one fire, the High Park Fire; an even larger number have been lost to the Waldo Canyon Fire (with no total currently listed on Inciweb or the Colorado Springs city site), and more fires burning, including the Flagstaff Fire very close to Boulder, Colorado.

______

Susan Tweit's article from Audubon, 2001 and still timely, on some of the effects of wildfire on the natural environment, plants and animals.

Notes from Colorado State University Vet Hospital on animals who found refuge there.