Deborah Robson's Blog, page 2

September 15, 2014

Iceland 3 - sheep roundup

Preface: The sheep roundups we saw were highlights of my time in Iceland, and also emotionally difficult for me. As much as we textile folk hear about Icelandic wool, the primary market is meat, principally lamb. Most of the four-month-old lambs born last spring leave the roundup area on trucks headed for the slaughterhouse, or abattoir. There was an abattoir tour as part of the North Atlantic Native Sheep and Wool Conference this year, as there was last year. The management of this aspect of sheep raising plays a critical role in the overall economic and welfare picture. Every farmer and shepherd I have met cares a great deal about the welfare of the animals, up to and including the slaughter. (Some don’t, of course, but I haven’t met them.) Part of me thinks that in order to have a comprehensive view of the world that I research I should fully understand this part of the cultural picture as well, and should not shy away from direct contact with the meat processing, but I have not been able to bring myself to do so. (I did visit the tannery, although I didn't take the tour or stay as long as others.) I don’t eat meat, for many reasons, and that choice has worked for me for decades. I do want to see increased use and valuing of wool—which I think is appropriate from multiple perspectives, including the ecological, long-term economic, aesthetic, and ethical. I suspect that if I forced myself to personally witness the meat-processing aspects of sheep farming I would not be able to continue my work, which I think is important—or I wouldn’t be doing it. I don’t judge the existing situation. I would like to see a shift in priorities and values in the larger economy. I’m perfectly aware that this is like somebody in a kayak wanting to change the course of a cruise ship (and I’ve paddled a kayak around an anchored cruise ship, so I know exactly what sort of size disparity I’m suggesting). What I can do is paddle my kayak, admire the sheep and the humans who care for them, and hold the hope that some of my actions may make a difference in the long run. But I need to leave the meat-related parts of this story to those who are involved with them. And so, other than to mention my personal challenges here, I will simply note—and not elaborate on—some aspects as we go through the roundup.

Roundup

Most Icelandic sheep spend the months from approximately May to September on their own in the common grazing areas. Flocks have assigned areas, and return to the same location annually. The types of landscape and quality of grazing vary, but all are remote. Familiarity with the environment likely helps members of the flock retain an understanding of weather patterns, sheltering areas, vegetation, and other aspects that help ensure the animals' survival over the summer.

In September, the sheep are rounded up and sorted by owner. The ewes are mated in the fall and spend the winter in shelters. Shearing takes place in the fall and again in the spring; the fall wool, cleanest and whitest, has the most value. Spring wool contains more vegetable matter and may be off-color, because it has been grown under more restricted conditions. After lambing in the spring, the sheep return to the common grazing areas.

Roundup schedules vary by common grazing area, and generally take four or five days of intense work involving sheep, humans, horses, and dogs. The sheep walk a long distance into the mountains in the spring—and walk a long way back in the fall to a sorting area; each grazing unit has its own facility, consisting of a large fenced pasture that initially contains the sheep after they come off the mountains, connected to a central, circular enclosure into which smaller groups of sheep are released for sorting, which in turn is surrounded by pie-shaped pens for the sorted groups. From these smaller pens the sheep are trucked off, either back to the appropriate farm (ewes, for breeding) or to the abattoir (most lambs and the older ewes who will not be bred again).

We watched two parts of the roundup process at two different locations: we saw the sheep coming down from the mountains in one area, and the sorting at another location. Here’s an overview of what a sorting area looks like, because you need to be able to get an aerial shot to comprehend the structure. That image is a pretty fancy one! They can be constructed from a variety of materials, including wood, concrete, or whatever is available that will be strong and durable enough.

From the rain-spattered bus window, we caught sight of one sorting area as the sheep were still coming down from the mountain but due to arrive in the foreseeable future. The building is a community house, which offered us some shelter while we waited. To its left, that big brown area contains the sorting pens. The sheep would be coming from the right and across the road.

After watching for an hour or so, we caught sight of the first horses and riders. At the far edge along the horizon, you can see the next batch, which turned out to be about a dozen horses that had also spent the season on the range.

Not too long after that, the lines of sheep began to appear.

They arrived in clusters, and spread out as they got near the road, where interesting grass grew.

They were encouraged to cross the road. . . .

. . . which they tended to do at a bit of a run. At this point, everyone involved was tired—sheep, people, dogs, horses. They’d been walking for literally days, and were ready for a rest.

Just the other side of the road, they were funneled into the large holding area, where they would spend the night resting up. Sorting would follow the next day.

Again through a rainy bus window: an indication of the way multiple generations were involved—both with the roundup and with the sorting. There were toddlers, and there were ninety-year-olds. It’s definitely a family and community event.

That was the first stage of the roundup, involving perhaps 30 people and 12,000 to 15,000 sheep. A number of days later, another, smaller group of people will go out and do a second pass over the same area. Finally a skilled pilot with intimate knowledge of the terrain will fly over, looking for more sheep and will communicate their locations to a smaller crew on the ground. Then that job is done for the year.

Now we skip to the other location for an actual sorting. The perimeter was lined with cars and small trucks filled with rain gear, picnic equipment, kids, and other necessities.

There are many more people involved on sorting day than on the long days of the roundup.

Interesting window sticker. . . .

Within the circular center section, representatives of each flock grabbed likely sheep . . .

. . . checked ear tags and earmarks (distinctive for each farm, and useful if tags are lost) . . .

. . . and put each sheep into the appropriate pie-shaped pen.

Some pens were fuller than others.

Sometimes the vegetation in an adjacent pen was more appealing.

Mostly the sheep were grateful to settle down once they’d been put in their assigned location.

Iceland has had problems in the past with disease transfer that have resulted in large-scale slaughter of animals. A number of measures have been put in place to prevent a recurrence of similar problems. Since before the middle of the twentieth century, no new sheep have been introduced to the country. If you see a sheep in Iceland, there’s no guessing game about what breed it is. In addition, the country has been divided into regions. Each region has a characteristic color of ear tag. Sheep that are missing identification or that have strayed from another region are placed in the slaughter group. In addition, most of the breeding takes place through artificial insemination. We did meet a farmer who breeds his ewes “the old-fashioned way,” buying in rams from the handful of disease-free locations from which it is possible to transport animals.

Speaking of transport, while there were large trucks arriving and departing with loads of sheep, going either to farms or to an abattoir, one nearby farmer transported ewes to pastures with a tractor-pulled trailer that needed to ford a fairly wide river (almost a small lake).

Here are two posts from Baablog, by a U.S. shepherd who participated directly in a roundup:

And here’s a post by an Icelandic farmer with a small flock.

Most Icelandic sheep are white, but we were told that colored percentages of the wool clip have recently increased some, to about 17 percent.

Some farmers breed more colored animals than others.

From the commercial wool-processing perspective, the most valuable fleeces are the solid colors. From a handspinner’s point of view, the multicolored ones have a lot of appeal.

White, black, brown, solid, or patterned, aren't they pretty sheep?

September 14, 2014

Iceland 2 - miscellany

The last post gave an overview of geography and travel. This will grab a few random impressions. The next one will dig into content. I’m warming up—!

Reykjavik served as base of operations for the beginning and ending of the trip. It has a lot of touristy shops, and some others, like the one operated by the Handknitting Association of Iceland, that warranted repeat visits. What gorgeous sweaters! Also mittens, hats, gloves. . . .

We also encountered samples of the Icelandic sense of humor, as in the Woolcano gift shop.

Icelanders need to, and do, take the extremes of their geological environment in stride. Lava fields are everywhere (there’s a remarkable and extensive one on the route from Keflavik airport into Reykjavik). It’s standard knowledge that IMO stands for Icelandic Met Office, and that “met” stands not for “metropolitan” but “meteorological,” an organization that issues regular, thorough updates. Eruptions, earthquakes, and floods—potential or actual—are part of everyday life.

Iceland presented more challenges than most places (other than, say, Idaho and Oklahoma) for the traveling vegetarian. Reykjavik, fortunately, offered up two restaurant treasures, both of which were also comparatively reasonably priced.

Gló: what can I say? I wish we had a place like this back home. The menu changes daily, and there are generally three major offerings, only one of which includes meat. Each is marked as to whether it’s vegetarian, vegan, and/or gluten-free. The cuisine features raw-food principles, and although that’s not something I know much about the results tasted great. You can choose just to have the main course or, as most people did, a main course plus your choice of three side salads, selected from an array of ten or more that change, depending on what’s most available. Adding the salads to the order only minimally increased the pricing, and resulted in a luxurious array of flavors.

We never got around to doing more than admiring the desserts. And on my last visit, I was asked if I’d like a frequent-diner card. Tempting, except that I was about to leave.

Just down the street from Gló is Garðurinn, a fully vegetarian restaurant, open only for lunch. The week’s menu is posted outside, with one soup and one other offering, each in small or large sizes.

Inflation means the Icelandic krona, or ISK, isn’t worth much. A comparatively inexpensive meal ran ISK 1200 to ISK 2500, which is equivalent to $11 to $21, or £6.50 to £13.50. At one location I paid ISK 1800—$16 or £9.50—for a bowl of soup and a small cup of tea. Fortunately, the soup was excellent.

For the days outside of Reykjavik, it was me and the grocery stores. I had let the conference know that I’m vegetarian so they wouldn’t include me in the meat count, but there wasn’t any way to accommodate alternate choices, so my challenge was (as it has been in other locations) to equip myself with food that was nutritionally balanced, tasty, didn’t require much refrigeration or heating, and could be neatly eaten on, say, a bus. Also that I could identify in an Icelandic store. Mainstays included various types of crackers and flatbreads, hummus, carrots, sweet peppers, apples, a bit of cheese, fruit-and-nut mixes, and, one of my new favorite foods that is unfortunately not available at home,* skýr. Skýr’s description makes it sounds like a variant of Greek yogurt: it’s cultured milk—in this case, skim—that has been strained. It’s smooth and thick. But it isn’t Greek yogurt. And the flavored skýrs I had in Iceland were nowhere near as sweet as the flavored yogurts in the U.S., Greek or otherwise.

* Siggi’s is marketed with both the yogurt and the skýr names on it, yet it’s different in texture and taste from what I had in Iceland. Apparently skýr from Iceland (or, if made in North America, under the auspices of the same source as the Icelandic skýr that I enjoyed most) is selectively available in some U.S. regions, not including where I live.

As I mentioned in a previous post, rainbows became a regular part of each day.

So did sheep, most of whom, however, were skittish enough that they’d turn tail and bound away when the bus passed by, even when they were in a fenced field and fifty yards or so from the road.

These were braver than average.

I got one slightly better photograph of Hofsjökull, the glacier on the east side of the mountain track on which we traversed the highlands. (Vatnajökull, the larger glacier farther to the east than Hofsjökull, is the one under which the current volcanic activity is taking place, focused on Dyngjujökull, an outlet glacier along its northern perimeter. Correct me if I’m wrong, please. Keeping track of what’s a glacier, what’s a river, what’s a volcano, and why the names overlap has been one of the challenges of this trip.)

Waterfalls, mountain vistas, breathtaking scenery—well, we missed a lot of that. As part of the return trip from Blönduós there was a tentative plan to stop at Gulfoss (a waterfall) and Geysir (hot springs), but we ran out of time.

Finally, on the last full day in Iceland, I got to see two of the country’s striking waterfalls. I was grateful to get a glimpse of what photos document and books enthuse about.

I’m pretty sure this is Seljalandsfoss. We didn’t have time to go up to it for a closer look, although what I read tells me that if it was indeed Seljalandsfoss you can even go behind it. That would be an experience!

A little farther down the road was Skógafoss, which we did investigate more closely because the turnoff also leads to Skógasafn, the folk museum that was our destination.

Thanks to the light rain that was falling, a here-again-gone-again rainbow complemented the plunging water.

Again thanks to limited time and the rain (which intensified during our foray), we didn’t climb to the top. Still: I got to see a couple of Icelandic waterfalls, and they were, indeed, spectacular.

September 13, 2014

Iceland 1 - orientation

The final eleven days of my trip ended up packed full of experiences. Two were essentially travel days. On the first I went from Scotland to Heathrow airport near London, then flew into Keflavik, Iceland’s international airport, and took a Flybus into Reykjavik proper. On the final day I reversed the Flybus route and then went by Icelandair from Keflavik directly to Denver. Oddly, as I arrived in Denver I realized that although I’ve done a fair amount of international travel and have frequently departed from Denver I’d never before re-entered the U.S. through that portal.

Because the nine full days I spent in Iceland were so crammed, I’m going to break down this series of posts into increments. Five of the days were dedicated to the North Atlantic Native Sheep and Wool Conference; two days before and two days after were available for other explorations.

This first post involves orientation: maps and buses (which relate to terrain).

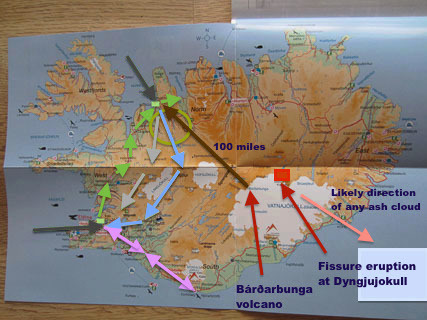

Here’s the basic map of Iceland. The white spots are glaciers.

Since August 16, a volcano named Bárðarbunga has been rumbling and earthquaking. The first question was whether I’d be able to get to Iceland if there was an ash-producing eruption, which could interrupt air traffic to the southeast—i.e., toward the U.K. and Heathrow airport. Later questions involved to what extent the conference might be affected.

Although we all monitored the geological status at least once a day, as it turned out the biggest immediate concerns were fog and rain, which kept us from seeing what I’m told was some fantastic Icelandic scenery that we drove through.

Here’s a marked-up map. Lacking refined tools and time to be precise, the markings are very approximate.

The dark gray arrows point to the places I stayed: Reykjavik at the lower left and Blönduós on the north coast.

The green arrows indicate our outbound travel path between the two locations.

The light olive-green oval indicates an area within which we did a lot of shorter trips, although it’s beyond me to figure out exactly where we were: why that’s the case will become apparent later in this post with some snapshots of the roads we were on.

The light gray arrows indicate the intended return path if the weather was bad (bad = snow, mostly).

The light blue arrows show the return path we did take, through the highlands and between two major glaciers.

One red arrow points to the volcano Bárðarbunga. The other red arrow points to a red square, indicating the fissure eruption that became active at Holuhraun (near the Dyngjujökull glacier) shortly before I arrived in Iceland and continues to erupt as I’m writing this.

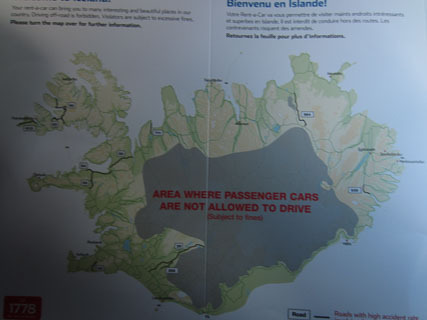

To amplify the above, here’s the map provided with the rental car that friends obtained for the last few days in the country:

The legend on that big gray blob says “area where passenger cars are not allowed to drive (subject to fines).” It overlaps a number of the areas we traversed. But not in a passenger car.

Last year I attended the North Atlantic Native Sheep and Wool Conference in Shetland (and was one of the presenters). When this year’s event was scheduled for Iceland and it became apparent that by slightly extending my stay in the British Isles I would be able to go there, it seemed shortsighted not to take advantage of the opportunity.

It has been true at both conferences that I’ve had access to experiences and sights that would be difficult to arrange otherwise—especially within such a short time, and in the company of other people who are equally interested and bring very different perspectives to bear on what they’re seeing.

Next year’s conference will be in the Faroes around the second week in September. I will say that getting information on the conference, registering, and so forth is not as straightforward as for many events. And also that hanging in through the challenges and uncertainties has been abundantly worthwhile.

During the conference, we traveled by bus. Our driver was Jóhann, and if there were an Olympic event in bus driving, he would be a clear contender for a gold medal. Where and how he took the buses . . . well, you’ll get a few glimpses. The rides were as smooth as the roads would allow and he remained calm and confident throughout. The travel could have been white-knuckle at many times, but only reached the raised-eyebrow stage now and then, always because of the conditions and never because of the driving.

Bus 1

Our primary bus, and the one we used for four of the days, was comfortable and versatile. (There was also a mini-bus at times with a few extra people.)

On the first day, I grabbed a seat right at the front.

This was the basic set-up during most of the bus journeys, beginning with the drive from Reykjavik to Blönduós:

Jóhann was in the driver's seat, of course. Oláfur Dýrmundsson, whom I’d met in Shetland last fall, sat nearby and offered commentary. (This is why I know some of what we drove through but couldn’t see.) Sitting next to him was one of the Greenlanders, who translated his commentary into Greenlandic for the contingent that didn’t speak English. Basic languages of the conference were English, Icelandic, and Greenlandic. Participants came from fourteen locales: Australia, Canada, England, Faroe Islands, Germany, Greenland, Iceland, Isle of Man, Norway, Scotland, Shetland, South Africa, Sweden, United States.

We enjoyed intermittently clear weather on that first day. And a fair amount of pavement and two-lane width, neither of which was to be taken for granted.

Not all roads looked like that.

Jóhann managed not only to get the bus into some interesting locations, but also to efficiently get back out of them. From my seat near the front, I was aware that he knew not only exactly where the corners of the bus were but precisely where each wheel was. He drove through some pretty chaotic situations, too. I don't think he ever even bumped a tire.

This bridge might have been 2cm wider than the bus. If that’s an exaggeration, it isn’t much of one.

He was with us for the full five days, and at least two of those required extremely long hours of driving.

Bus 2

On the fifth day we got on the bus—but it wasn’t the same bus. “More rugged,” we were told.

Okay.

Some of the roads were only a notch more challenging.

The next photo, however, is not in focus because it couldn’t be: too much shaking going on. That blue isn’t sky: it’s the tinting at the top of the windshield. That’s the Greenlander who translated, sitting behind Oláfur. I’m in about the third row of seats back. See the road?

Someone commented that if we’d brought raw milk with us we could have made butter in no time.

After a bunch of that, we reached a high point, and while we were taking a break (and most people were outside the bus) Jóhann quietly walked down the bus and hooked plastic bags on about every other seat. This was a sign that the roads for the rest of the day were not going to be better.

And they weren’t, although I’m not aware that anyone needed to use any of the bags.

The bus forded this stream: no bridge.

It was cold and rainy and fog obscured the mountains and we only got a hazy glimpse of one of the big glaciers we passed between, when on another day we might have clearly seen both.

(There’s a glacier in there. That’s about what we could see: just a change in the way light reflected along the horizon.)

I developed an even greater admiration for Icelandic sheep, because most of what we traveled through was common grazing land, where the sheep spend about four months of the year on their own.

There are two sheep in that picture. They're pretty easy to spot, if you can believe you're seeing 'em. Often there were threesomes: a ewe and twin lambs.

Chilly precipitation, and a lunar-bleak rocky landscape. The sheep in this area would not be rounded up for another week. By this time of year, the plant matter (such as it is) is losing its nutritional value.

Yes, that's the road along the lefthand edge of that photo.

Once in a while we got a fairly clear view of where we were.

Occasionally it got almost bright.

And during the week as a whole, we saw disproportionate numbers of rainbows.

September 12, 2014

Scottish Highlands 2

A welcoming sight in a B&B: a well-behaved rescue Border collie who knows where to hide herself when there are guests who are not comfortable around dogs . . . and where to get comfortable (below) when the guests display a distinct fondness for good dogs (and might possibly be missing their own). (Trying to link to Larick House in Newtonmore, but the internet here is too slow.)

The Highland Folk Museum has been on my wish list of places to visit for several years, since a friend came back from Scotland with enthusiastic reports about it. It’s an excellent place to spend parts of two days, even in a gray drizzle.

Buildings and equipment have been relocated to the site or constructed here to represent several periods in highlands life. The structures extend along a pleasant walking path that covers quite a distance (about a mile), so we got a strong sense of transition between the periods and focal areas.

We began in the afternoon of our arrival with a simple reconnaissance trip to get the overview, check out the shop (and buy a guide to read that evening), and see the sheep. Several Scottish Blackface and one Soay share a pasture. We asked about the sheep, and there used to be more Soay but just the one is left. A friend of mine is looking for a no-kill home for some young Soay wethers, so I wrote her and suggested she might get in touch with them. . . . We’ll see what happens. . . .

The next morning we began with the early- to mid-twentieth-century buildings. Most of these were from a generation or two before mine.

The intimacy of the museum impressed me.

The site includes open areas, sheltered spaces, and woodsy sections.

I wanted to inflate the bike’s tires and take a ride. Although I’m guessing I’d need to install new tires first. (I miss my bike, too.)

One of the reasons I enjoy having a focus when I travel is that I can follow a theme. That (usually) keeps the constant flow of new information from being totally overwhelming. It’s easy to take looms for granted; most people take textile technology so much for granted that it’s completely invisible. In this trip, I’ve enjoyed noticing a variety of weaving systems, from warp-weighted looms and tablets through “standard” four-shaft looms (counterbalance, countermarch, and jack) to pedal looms and later, more fully mechanized mill equipment. (I’m thinking here of Shetland and Wales, the latter still awaiting a write-up, although I’m also undoubtedly forgetting some specifics because I’m an hour from departure from Reykjavik and the past weeks have been full to overflowing.)

If I’m recalling correctly, this loom, in use, occupies the Craig Dhu Tweed Shop (center section of the museum).

After we’d wandered through all the available buildings at the 1900s end of the site, we headed down the forest path toward the eighteenth-century township, looking for red squirrels. There was at least one!

This busy soul offered photographic challenges. It’s amazing that any of my images worked out. I have a lens that does zoom but loses resolution rapidly after a certain point, which I had to exceed by a lot in order to catch any squirrel imagery at all.

Within the woods is a Travellers’ camp.

The tent, unexpectedly spacious inside, in shape and function (if not materials or construction) resembled buildings we saw later in the township.

Late in the season as we were, only one costumed interpreter needed to hang out in the light rain of the township answering visitors’ questions.

One of the roofs was being reworked. Smoke drifted from a chimney.

I love seeing the details of how people solved construction and living problems, often with elegant and aesthetically pleasing combinations and arrangements of materials.

The weaver’s space seemed very dark when we first stepped into it, but as our eyes adjusted I could see how it would be possible to work there, although I’d still prefer more light.

On our way back through the woods, we caught sight of what might have been the same red squirrel—or not.

In addition to the museum, we visited the Wildcat Centre back in the town of Newtonmore. Scottish wildcats are endangered, and people in Newtonmore have thought of several good ways to bring attention to the situation while also increasing visitors' reasons to come to and stay in the area. They have a facility with excellent information, and they’ve created a walking tour focused on the cats. . . .

. . . and also community members have painted cat figures that are located over an extended area. The figures are the size of an adult male wildcat, which is pretty large. Each is different, and you can pick up a map at the centre and mark the number of every cat you find at the appropriate location. If you locate a certain number, you get a certificate or prize. Kids apparently love it, and I could see having fun with it as an adult. We found one next to the Travellers’ camp. Others are easier to discover: in store windows, for example.

It was time for more driving. I enjoy the critter signs along the road.

Especially these. . . .

. . . and there was one for a frog crossing that I didn’t get a snapshot of.

We turned in the rental car a day early in order to have a bit of time to regroup (repack, do laundry, take a walk that was just a walk).

Note: I drove more than 500 miles in the highlands, in a righthand drive car. On two occasions, there were headlights coming toward me on my side of the road. Both times, the other driver was the one in the wrong place and all positioning got straightened out in time. Whew!

Magnus accepted some affection, within his limits (while guarding knitting).

And generous friends even got me to the train station to catch the sleeper into London, for the next leg of my journey (in a light rain). The train to Aberdeen had been cancelled, but my train was fortunately running, and on schedule.

Scotland : London Euston station : London Paddington station : Heathrow : Reykjavik.

September 11, 2014

Scottish Highlands 1

The time came to leave Shetland.

I flew into Aberdeen, rented a car, and met up with Jeni Reid. As I noted in an out-of-sequence post earlier, we went to visit a flock of Valais Blacknose sheep, which were hard to photograph only because they were so friendly.

We tore ourselves away and kept moving west. We drove a lot of roads that are closed or impassable in the winter. These are the sorts of places where sheep ramble around without fencing. It reminds me a little of parts of the American West, where if you want to keep livestock off your property, you fence them out.

Scottish Blackface sheep crossing the road. . . .

We stayed in a hostel and came across a flyer for what became one of the highlights of the trip: the Knockando Woollen Mill.

What a treasure! It’s a restored historic site and a fully functioning mill.

(The shadows across that image are cast by bunting made of rectangles of fabrics of the type produced at the mill over the years.)

There’s a mule spinner to make the yarn. . . .

Looms to weave fabric (still working after more than a century). . . .

And machinery for finishing fabric. . . .

I love the way natural teasels are still in use to brush fabrics, and not just at historic sites.

The mill is such a pleasant place that people from the area come there just as a place to visit. The lovely gardens are created by volunteers. The food in the café is worth the trip all on its own. And the interpretive film shown in a room adjacent to the shop is so good I bought a copy on a USB drive to take home. The Knockando Woollen Mill is a class act, all the way through.

We continued west on increasingly smaller roads, heading for the northwest coast of Scotland.

The highlands are beautiful in August.

Yes, it rained. . . .

. . . but it also sometimes didn’t. The afternoons tended to be clearer than the mornings.

We went to visit Helen Lockhart of Ripplescrafts. We’ve connected through Twitter for quite a while, and after saying we need to meet in person sometime, we finally did.

Helen works color magic in her compact and well-organized studio-shed.

Although, given the weather, she has to be creative about where and how she hangs skeins to dry.

There were also some inside the house.

The tent arrangement has been the site of some interesting corollary events, like when a wren made her nest inside a skein. After she was done with it, it went on display in the natural history exhibit in a nearby town.

Because the afternoon sky was bright, we rambled up to a high spot for a look around.

Lexie chose not to join us.

Peggy did.

Sunny and breezy!

With sheep at the same elevation. (Cheviot.)

Jeni and I also took an evening walk down to the bay, where she undoubtedly got better photographs than I did, although some of mine aren’t bad.

Scarp, who is one of the best dogs on the planet, went with us.

He does not chase sheep.

Which is a very good thing, because they are everywhere.

Adjacent to the friend’s house where we were staying are both a classic phone booth (which turns out to be a good place for cell phone reception as well as a functioning land line) and a post box.

So I wrote and mailed a couple of postcards from the top of the world.

It’s a gorgeous place, and I got quite proficient at driving single-track roads.

More Scottish highlands to come.

September 8, 2014

Rambling around Shetland, 4--sheep

While I was in Shetland, I also watched sheep—in addition to those I saw at the Cunningsburgh show. I could have spent the whole time running around looking at flocks, but I had other types of research to do that needed to precede the conversations I might have with the sheep and their people (for the most part). I did visit some flocks. But I also simply noticed which sheep were where.

This black sheep was not where it belonged, nor where it wanted to be.

It was actually loose, and able to get out onto the main road leading to the airport (the A970, which is the main north/south route). In the photo above you can see the road with the airport beyond it. Lots of sheep ramble around without fencing in Shetland, but not intentionally in locations like that. So before I went to the Jarlshof historic site, I stopped in at the nearby Sumburgh Hotel (which looks like a terrific place to stay) and asked at the desk if they knew who to notify about the errant sheep.

They got in touch with the owner. I noticed a while later (while I was touring Jarlshof) that he came by, and then there were three sheep outside the main enclosure, but all effectively blocked from getting to the road.

Those are sheep in Shetland, but they are not sheep of the Shetland breed. They are also in a location where there is grass and where their welfare can be monitored on a regular basis. The “which sheep are where?” question hinges, for the most part, on those two factors.

These Suffolk tups (rams) grazed in lush surroundings near the Crofthouse Museum: again sheep in Shetland, but not sheep of the Shetland breed.

Of course, I saw plenty of Shetland sheep of the Shetland breed as well. A number of Shetland tups were in inbye fields (inbye being close to houses, as opposed to hill-grazing areas), enjoying some feasting before they go to work in the fall ensuring that there are plenty of lambs next spring.

However, Shetland sheep are easiest to find if you get out away from the main human habitation areas: away from two-lane roads, and into places where there are single-tracks with passing lanes. Rumble across the subtle barrier of a cattle grid* and start driving more carefully, because sheep will be next to and wandering on the road. I don’t know if there are any other breeds in these areas, but I doubt it. Many people assure me that any other type of sheep won’t survive in that environment and without closer attention. Shetlands have a reputation for hardiness.

* British English. US English = cattle guard. Called this even when it’s sheep that are being kept from crossing outside the area.

I went to visit a flock that is fenced but lives on rougher pastures than the inbye sheep. These are the ewes. . . .

. . . and these are the handsome rams.

They’re owned by Mary Macgregor, who has published a book of Fair Isle patterns collected by Robert Williamson and whose croft is as close to Foula as I got.

On the way to see Mary and her sheep, I also passed a spot where a flock had been gathered for shearing. These are the post-haircut crew. I counted six shearers working, most with hand shears although at least one set of electric shears ran off a generator.

Nearby were some question marks. There appeared to be a mix in this field. That’s likely a Shetland on the left. The one in the middle has a Texel-y appearance (face, set of the ears, and stance). The one with its head down has four horns. There are genes for this in the Shetland breed, but they aren’t common. The tail would provide additional information, but the photo doesn't show its shape clearly enough and I didn’t take the time to get permission to go into the field or to simply ask the owner. At that moment, I didn’t really need to know; the pieces of information I filed mentally were “mixed flock” and “interesting horns.” Again, this was pasture, carefully maintained, and close to the relevant house.

In Shetland-spotting, the first giveaway is location. Another clue: color. White Shetlands abound, but colors also appear frequently, especially in the hill sheep. (Inbye Shetland sheep tend toward the white and moorit, or solid brown, and at this season were often rams. Colored sheep could also be Zwartbles, but they’re bigger and have a characteristic marking pattern of white-on-black—not at all like the markings on the sheep below right—and will be in the cushier digs.)

Shetlands (through the windshield):

Shetlands:

Shetlands (the fence is behind them, and I took the photo from the road):

Shetlands, wandering around on top of a fairly bleak hill reached by a gravel, potholed road, and home to telecommunications sites, both currently functioning and abandoned:

Shetland, sheltering, not far from those other two:

Driving down the other side of that hill, different types of sheep began to appear as I got lower and closer to where people were living. These are likely Shetland-Cheviot crosses.

These are Shetlands (great color on the righthand one).

Scottish Blackface: another sturdy breed, able to live on rough turf, but not let loose on the hills with the Shetlands for many reasons.

On St Ninian’s Isle, a mix of crosses, with lots of green to eat and not too far from the tending humans.

Another thing that I became more familiar with was the predators that cause the most losses of lambs and weak sheep. For the most part, in Shetland that means birds, and I suspect they are primarily a problem to the hill flocks.

For example: the bonxie, or . This one was flying over St Ninian’s Isle.

Another concern is (and PDF here). I’m pretty sure that’s what these were; I’m only a casual birdwatcher, but the only crows in Shetland are , which can also do a lot of damage to a flock, and they aren’t all-black like these birds (which I saw before they took flight).

Understanding the threats to a breed of sheep is also part of getting a good idea of what “hardiness” means and what influences people’s decisions of which types to put in particular environments and how to manage them.

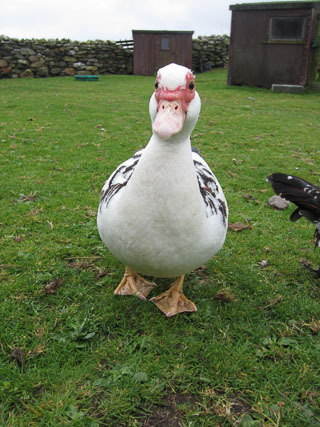

Ending on a more directly sheep-y and positive note, I did get to visit with Mary and Tommy Isbister at Burland Croft Trail, and their sheep (it was their poultry I met with earlier in my trip).

On my walk around the croft, I met up with some caddie lambs (bottle lambs in North America). This one had just had a good snack and had a face and neck covered with milk-spray.

While I was out at Mary’s, she took this photo of me. Windblown, but not rain-soaked.

Even the rainy days were good for sheep-spotting, although the clear days were better. I saw a few hundred sheep, maybe a thousand. That wasn't enough, but it was all I could fit into this trip.

September 4, 2014

On not getting to Fair Isle or Foula

This post is about why I didn’t get to either Fair Isle or Foula, two of the locations on my “must see” list when I arrived in Shetland. They're both islands that are part of Shetland but at some distance from the primary vertical cluster of islands. I did know that “must see” would have to be as flexible as everything else on my list. Getting to each of those locations requires the cooperation of the weather.

Access to both is by boat (mailboat or passenger-only ferry) or air. Going by sea takes much longer. The air option is more likely to be cancelled or aborted by weather conditions. Neither runs daily, even when everything is on schedule, which it was not during my time in Shetland. You have to think ahead about what day it is, which transportation methods are operating, and whether your choice is likely to successfully reach its destination or need to turn back.

For Fair Isle, the friend I intended to visit there said that I would need to plan to return to Shetland’s Mainland at least five days before my scheduled flight out in order to leave room for delays. Thus any trip to Fair Isle would need to happen within the first part of my Shetland time. As it turned out, my friend was on Mainland herself during those days, because she had meetings that she needed to be at and couldn’t otherwise be sure that she’d be able to be on the right island at the right time. (We did have opportunities to visit during my travels . . . in Lerwick.)

Foula can ordinarily be visited in a day trip—but only, in that case, by air, because the ferry takes too long and doesn’t run daily. Again, which day and the weather have to be taken into account. Other factors intervened there.

So here’s what I saw of Fair Isle and Foula, and how I saw them.

Fair Isle

When I came out of Jarlshof, the multi-layered historic site near the south end of Shetland’s Mainland, the day was so clear and beautiful—and I’d already spent so much time indoors—that I decided to check out the coast hiking trail to Sumburgh Head.

It’s well marked, if, as you can see, not trodden into a thoroughfare.

I made it about halfway along the route from Jarlshof to the lighthouse on its promontory when the narrow trail began to follow the edge of a precipitous drop-off that was located on the same side as my more-arthritic hip. In addition to the fact that it was a long way down onto a bunch of rocks in churning water, I hadn’t told anyone where I was going. And it’s true that people are lost off Shetland’s cliffs into the sea (due to wind, most often, which doesn’t rule out just a slip of the foot). I didn’t want to be an object lesson for future visitors, so I called it a good walk already, turned back, retrieved my little rental car, and approached the lighthouse by road instead. Because the car park (parking lot) is at the bottom of a hill, I got another good hike in up to the top.

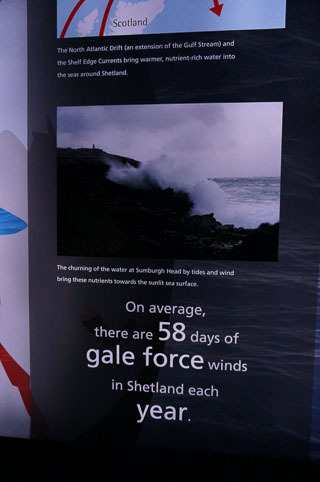

Weather is the topic of one of the many excellent new exhibits at Sumburgh Head.

From the rocky cliff just south of the lighthouse, I got a good look at Fair Isle on the horizon.

Here’s a closer look to distinguish it from some of the lower clouds.

Even when the weather is fine elsewhere in Shetland, a flight to Fair Isle can be forced to turn back because of suddenly appearing fog. I think the island may attract fog.

I took that photo on one of the clearest days during my two weeks in Shetland: I likely wouldn’t have made it to Fair Isle even if I’d planned to go then. (This was also three days before my departure flight to Aberdeen, so it wasn’t an option anyway.)

Foula

Foula was complicated for other reasons. As I mentioned above, going over and back in a single day by boat isn’t an option. In addition, air service is currently curtailed.

The folks (and sheep) I wanted to visit were also dealing with the aftermath of a fierce rainstorm and some flooding. It was not the time for me to come barging in, even if I could have arranged to get there.

I did get a nice clear view of Foula from the west side of Mainland on a clear day.

This is the same day, and a closer view of the island, although obviously the cloud situation and shimmering light have shifted.

On the following day, I got another glimpse of Foula from St Ninian’s Isle.

It’s out there somewhere. I could just make it out when the subtle shifts of light put enough contrast into the shades of blue-gray.

A few more notes

Shetland is diverse, variable, and splendid. It behooves one to be aware of the hazards, a few of which are marked.

Lerwick and other establishments have enjoyed both bright days and battering here for a long time—humans and sheep have been living in Shetland for millennia. To understand the sheep, it’s necessary to understand the environment. I got more experience with that during this trip, which still only allowed me experience of the moderate types of weather.

The photo above was taken a few yards from the photo below, on a different day.

(The reflected building in the water just above isn’t the same one as in the preceding picture.)

I don’t think rainbows ever become commonplace, but I saw many: in this case, a double one with both full arcs visible.

One representing Fair Isle, and one Foula?

I may need to find a way to try again on those goals.

September 3, 2014

Rambling around Shetland, 3--flexible planning

The key to success for my recent trip to Shetland consisted of two parts: (1) a series of goals, defined yet amenable to constant modification, and (2) a very flexible schedule.

For example, on my first visit to see a particular flock of sheep at Burland Croft Trail, it was raining; I didn’t have the right boots on (because I didn’t actually think I was going to find the location); and while we had an "any time" agreement, my inadvertent arrival coincided with a time when the people I meant to see had needed to run into Lerwick unexpectedly.

So between raindrops I met some other members of the extended community.

And we had some nice conversations.

Including a bit of group discussion, as the weather permitted.

Although even the Shetland natives ran for cover when the sky-water got more enthusiastic.

I went into the shed, where there was information on the croft and its activities, and a pile of beautiful fleeces. I got answers to a few of my questions just by looking at the fleeces.

And I went back another day, shortly before I left Shetland, and enjoyed a lovely visit with Mary and Tommy Isbister and their sheep. I also got to see photos and the actual garments for a number of one-of-a-kind creations made by their gifted daughter Sanna Isbister, who lives in West Cork, Ireland. (I bought giclée prints of two of Sanna’s paintings, one of Gypsy—an image you can see on the site—and one of a young Shetland ram. Ah, it can be found, too: “Kenny,” here.)

Then there was another day when I set out to do something . . . right now I don’t remember what it was, but it wasn’t possible, and that impossibility may have involved rain . . . so I went to Jamieson & Smith to peruse the fleeces downstairs in the room that has the handspinners’ selection.

This time of year is part of the shearing season. As I arrived, a truck pulled up with a trailer full of wool.

I’m not entirely sure where they offloaded the bags, because every available cranny was already crammed. In fact, it wasn’t so easy to get to the wool room downstairs, because of the massive piles of wool. J&S could use some more space. They might get it some day, but it sure isn’t there now.

So instead of heading down to the wool room, I spent the morning with wool buyer Oliver Henry while he worked on mostly grade 2 wools (grade 2 going into the baler, with some grade 3 behind him, and grade 4 and also the finer fleeces going into nearby baskets).

I hope I was somewhat helpful with activities like moving bales around and/or out of the way, including at one point assisting in digging the scale out from under a small mountain of wool so it could be used.

A couple of hours later I made my way between bales to the downstairs and found a bit of wool to ship back for workshops.

At the end of that same day (not raining much right then, but my energy was lagging), I went to the Shetland Library to see what interesting things they had. I'd already made my first couple of trips to the archives, and in the course of my rambles had learned about a couple of documents I wanted to see that were at the library. I found some others, too.

One of them was a document about a marketing scheme that was never implemented. Nonetheless, it provides insight into some of the history of Shetland sheep and wool.

Sometimes what didn’t happen can be as important as what did.

On another day, I simply needed to take a break, and it was a gorgeous day for a change, so after visiting I ended up at Sumburgh Head, at the far south end of Shetland’s Mainland. I missed the annual puffin visitation by a few days, but it was beautiful with and and , among other avians.

There’s a lot to see and learn at Sumburgh Head about natural history and lighthouses and more. And even more.

Although I need to stay focused on sheep and wool to make progress with my work, I also need to understand the contexts and cultures of which sheep and wool are a part. That means a certain amount of serendipity is useful—the trick is always figuring out how much is enough, and when I’m being pulled off track instead of just deepening my thought processes.

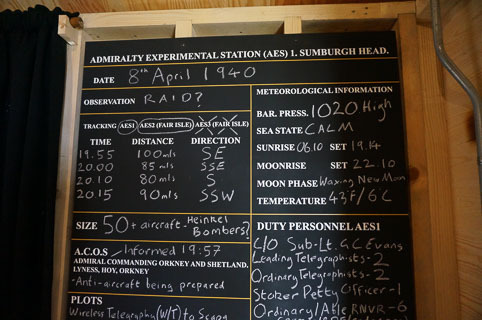

This visit was definitely in the latter realm—the good kind of peripheral excursion—because bits of knowledge I’d accumulated previously clicked into new thought-constellations. One of the exhibits where that happened was the radar hut, about the then-new technology and its importance in World War II. Last year on my trip to Orkney—the group of islands between Shetland and mainland Scotland—I had learned about the British fleet being at Scapa Flow in 1940. But being in the place where the intelligence was discovered that prevented its total and sudden destruction—a tiny building, staffed by young people with equipment so new they weren’t entirely certain how it would work—connected a lot of dots for me and stands out as a non-fiber highlight of this trip.

There are more dots of this type that I would like to connect in the future, some of them having to do with the Shetland Bus, an important part of the Norwegian resistance movement (also during World War II).

As is becoming very apparent, I did sort my ideas of where to go and what to do by what types of weather would accommodate the activities. And on another drizzly day, I made my way to the Shetland Crofthouse Museum, representing a croft of about 1880.

I learned a lot on this trip about crofting, which (to oversimplify) is the traditional agricultural/residential portion of many Shetlanders’ lives. It’s not farming, in that crofting represents only a portion of what a family would do for a living. And crofting has a lot to do with the ownership and management of sheep and of different parts of the landscape. I have a post in process that will provide a bit of information on what sheep I saw in which locations. Crofts are a big part of comprehending what goes on with sheep breeding, and therefore wool production and textile crafting.

Speaking of which, there were sample garment stretchers hanging by the fireplace in the croft house museum.

Up on top of one of the box beds was a spinning wheel—and, over on the right, a sweater frame.

Looking UP in historic residences of this type often results in the discovery of textile equipment. It’s nice, though, when the textiles themselves are a significant and appropriate part of the eye-level setting as well, as is this hap (everyday) shawl on a stretching frame.

I stayed a bit longer at the museum than I planned—and didn’t get down to the water mill—because it was pouring. But when the rain let up, I got another reward for looking UP.

August 31, 2014

Rambling around Shetland, 2

When I was in Shetland last October for Shetland Wool Week, there was so much going on that I didn't have much opportunity at the Shetland Museum and Archives to do more than notice where the textile collection was and wave "see you later" at it. This time I followed up on that promise.

Then and now, I did take a close look at the reproductions of the Gunnister Man's clothing. On this trip I was also able to get some of the back story on the recreation of the textiles from curator Carol Christiansen (here's a PDF about the project).

The only items in that case that have not yet been fully re-interpreted are the gloves on the figure's knee. Those are placeholders.

We talked about the detailed work and testing involved in finding fleeces that would behave in the ways necessary to replicate the effects of the original clothing, which took a lot of trial-and-error. The clothing in its finished form has even been "worn" appropriately.

After renewing and deepening my acquaintance with the Gunnister Man figure, I briefly reviewed all the exhibit cases, looking for textiles. I found quite a few incorporated into the stories about numerous non-textile topics told within the delightful museum—and look forward to another visit in which I'll be able to see even more of what it has to offer.

One thing I enjoy discovering is the tools that people in the past have used for wool preparation and spinning—for example, these combs (kems) from about 1750 to 1800.

I love spotting niddy-noddies as well, like this one from Lerwick, 1880 to 1920 (called a hesp tree).

And carders, these from Unst (the northernmost island in the Shetlands), from about 1900 to 1940.

Breathtaking laces and Fair Isle garments nestle in the cases and more can be discovered in the drawers and pull-out vertical displays. It's like exploring a treasure-trove.

Among the unusual pieces was this veil (1851):

One example (with incorporated magnifying glass) represents what may be the finest lace-knitting ever.

And while I was examining a particularly intricate and beautiful Fair Isle vest, a member of the museum staff came by and said, "My aunt made that." This sort of happening is part of what makes a visit to Shetland intriguing and multifaceted.

In addition to the textile collection at the Shetland Museum and archives, there is the Shetland Textile Museum, located in a structure called the Böd of Gremista.

This museum also packs a lot into a small space. It's different from the Shetland Museum in both its narrower focus and in placing a strong emphasis on the links between historic and contemporary textiles and workers.

One of the current displays involves mittens and gloves from a variety of northern European textile traditions. Perhaps most curious for me are the plain brown gloves in the center, which were made from horsehair. This led to a discussion of the feasibility of spinning the winter undercoats of Shetland ponies.

My interest in the origins of domesticated sheep, and of the history of the human/animal bond and interdependence, leads me to visit places like Jarlshof, a complex site with layered evidence of more than four thousand years of human habitation. Even the oldest archaeological remains indicate that sheep were present. But what kind they were is still, and may forever be, unknown.

The weather continued to vary. The day I spent exploring Jarlshof and nearby Sumburgh Head was the only really clear and bright day of the trip—and came at a fortunate time, because by then I needed to be outdoors, having spent a lot of time in the museum, archives, and library.

But there were special pleasures as well in the rainier days.

August 29, 2014

Rambling around Shetland, 1

During my time in Shetland, I focused on things I could not do elsewhere, because the time was short and precious. But there were also hours when none of the places I needed to access was open, or errands needed to be done (food, post office, map acquisition), and so on. Also my lack of familiarity with places to park in Lerwick meant that I left the car where it was easy to find a spot and walked to the other places that I needed to be—combination local-area transportation, exercise, and simply looking around (which can be informative).

Shetland weather varies a lot. During most of my trip, and for most of the places I needed to be, it was rainy.

That said, often it was possible to wait half an hour or drive five miles and be in a different microclimate.

Example above: fogged in on the east side of Mainland, and clearing on the west side.

High Level Music is a shop in downtown Lerwick that I hadn't had time to visit before, and which I'll need to explore more on the next trip. At least I got into it and looked around on this journey. (Although technically the address is Gardie Court, it's part of the Commercial Street area that is almost completely limited to pedestrian traffic.) I wish I had more time in my life for music!

Of course I stopped in at Jamieson & Smith early in my visit (and later, too). It's shearing season, so there was almost no room to maneuver in the wool sheds.

So Oliver Henry, the wool buyer, brought an unusual fleece into the shop area to show me. Sorry he's tilted, but I wanted both Oliver and the fleece, and I'd backed up as far as I could. . . . (If you like wool and/or sheep, don't miss the link at the beginning of this paragraph.)

Jamieson & Smith introduced a worsted-spun fingering-weight yarn a couple of years ago at Shetland Wool Week. They are now making (but have not officially released) a worsted-spun Aran weight. I bought a ball and swatched with it—the first of two swatches from this yarn that I'll make for my breed-specific reference collection.

That gave me the idea for another experimental project. This is the first attempt, although I've since started over with a slight modification. I'm using the fingering weight because I needed both worsted- and woollen-spun yarns of the same weight in the same color. I'd intended to use a lighter color, but this green was the best choice to limit the variables (thanks to Ella Gordon for helping me quickly narrow down the options once I'd given her the outlines of my idea).

The pattern is Martina Behm's "Leftie," although instead of doing color contrasts I'm alternating the worsted and woollen yarns.

On the next iteration, I've made a slight shift in the pattern so that the different qualities of the two types of yarns will be more evident. I'll show more photos later, after it's farther along (it's coming nicely).

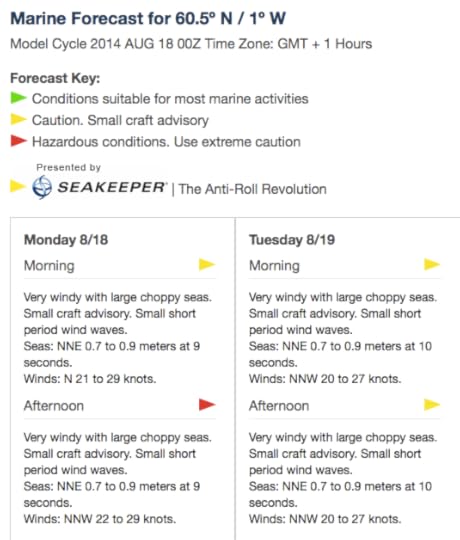

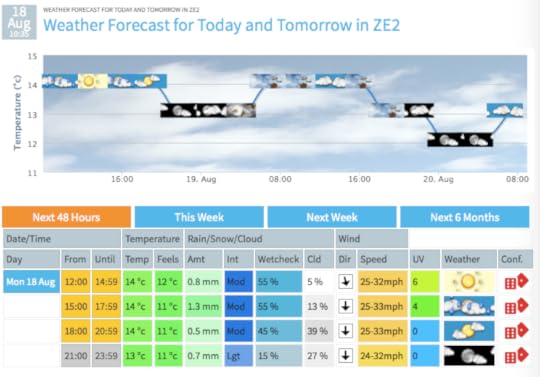

I perused a lot of weather forecasts while in Shetland. The Norwegian maritime forecasts seemed to be quite good, overall.

Still, the best way to figure out the weather was to look out the window.

And then figure it would change before I got my boots on and went out the door.

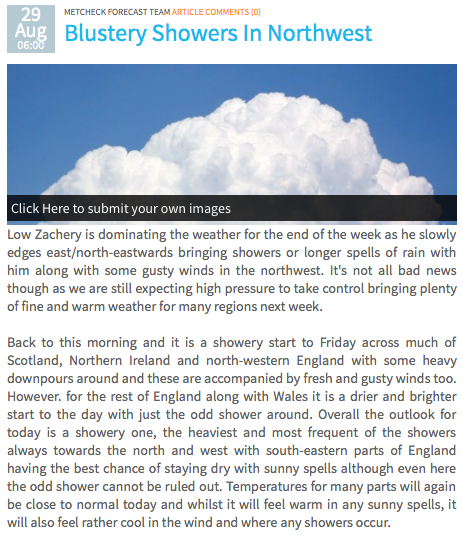

The Metcheck forecast system had a whole lot of appeal in the graphics-and-usability department, although I wasn't in Shetland long enough to really get adept at using all the content. The windspeeds turned out to be extremely useful. The rain projections were averaged over the whole area, and real-time evaluation out the window worked better for planning.

Here's today's Metcheck narrative overview for northwestern Scotland, which is where I am:

A look out the window a short while ago suggested that it's accurate.

Yet the drive down the coast may be pretty anyway.