Deborah Robson's Blog, page 13

January 26, 2012

How I came up with the numbers I used in The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, part 1

I've been promising, or threatening, to write a post about how I came up with the numbers used to describe the fibers in The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook—you know, the parts in the boxes, where the text talks about fiber diameters, staple lengths, fleece weights, and the like.

The short answer is that . . . well, there isn't a short answer. The shortest is that I didn't just copy numbers from somewhere else. Instead, I did research, drew on almost forty years of experience looking at and handling wool, and came up with numbers that I thought would best represent what a fiber person (for example, me) could expect to find.

Two decisions, one philosophical and one practical, set the foundation for my work with the numbers.

Philosophically, I wanted the data we provided to reflect what fiber folk were likely to hold in their hands: in other words, to give a reasonable ballpark idea of the range of fibers an animal, or breed, is probably growing.

From the practical perspective, I wanted a consistent approach to underlie all the sets of numbers.

Co-author Carol Ekarius and I had already spent months deciding what would be on our list of animals to cover.

The first thought that arises for anyone engaged in such a quest is to use the numbers published by breed associations. Yet those aren't available for all breeds and not all types of animals have breed associations. In addition, those numbers may reflect a particular group of people's ideal for judging animals in the show ring, not what's showing up on the shearing floor.

What comes next is wondering how people who have written down numbers before have decided what to use—but that lasts only a moment, because in almost all cases the back stories can't be discovered. A reasonable approach would be to choose an ostensibly reliable source and copy its numbers. I've done this in the past, as a result of personal curiosity and for my own notebooks, and it takes a long time.

Yet this time I was responsible to more than my personal curiosity—or, rather, to new levels of that curiosity as well as to a potential community of fellow fiber-users. So I moved to a new level that involved gathering as many numbers as possible for each type of fiber from a wide variety of sources, and then taking a look at them to see if I could discern patterns or irregularities.

To demonstrate my process, I'm going to use four sheep breeds that presented radically different problems in deciding what numbers to use:

a very consistent breed (Cormo)

a breed with a lot of variety (Romney)*

two breeds with almost no data (Santa Cruz and Hog Island)

* If I'm feeling brave when I write up the "a lot of variety" section, I'll mention the Cheviots again. . . . Does it indicate anything that, when I went to link to a blog post about the Cheviots, I could remember the EXACT MONTH AND YEAR when I had a serious tussle with their identities and data? I have a good memory, but for things like "when did I write that specific post?" I generally need to refer to my notes. Not in this case.

___

The numbers part of writing The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook operated as a separate sub-project and had its own dedicated working spaces, including a physical folder:

It was about 1.5 inches (4 cm) thick. Inside were sections with pockets:

It also willingly held a few extra manila envelopes of papers.

I happened across this organizer while I was buying yet another dozen cardboard file boxes to hold fiber samples. I bought it on a whim, feeling extravagant because I had no precisely defined use for it. It became a reliable sidekick. Although the data it held was partnered with a lot of computer files, my thinking processes took place with the help of the papers it protected.

As I mentioned, I began by simply gathering data presented by other people. I looked at the Oklahoma State University site and at Wikipedia, of course, in part because many fibers are listed and it's nice to start a search with success (or to be warned that the digging will need to be deep). It was interesting to discover later what the sources of these sites' data were—when I located matching material elsewhere that appeared to predate the compilations. I was able to perceive this cross-linking between sources (print and web) from time to time throughout my research, and it helped me evaluate and weight my results.

Then I consulted as many breed and trade associations as I could locate, performed multiple web searches, and prowled through a couple of shelves full of books. Repeatedly.

When I had exhausted at least myself, if not the options (although I worked to plumb those as deeply as I could), I assembled in a spreadsheet the data I had found for each type of animal or breed of sheep.

___

Example 1:

Cormo

Cormo is a relatively modern sheep breed developed with strictly defined performance standards, including for the quality of the wool. Individual animals that don't meet those requirements are culled. You'd think I could have almost instantaneously processed this breed through the numbers-cycle. While it was easy relative to other fibers, it shows that none of my decisions worked by cut-and- paste.

Sometimes I obtained information in imperial designations, sometimes metric, sometimes the Bradford or USDA numbers. (These two systems use the same notation system, although they are not completely interchangeable.) I started by putting whatever information I had on one sheet of paper (well, sometimes, as for the Romney, two sheets of paper).

Here's my Cormo list, in its neatly presented spreadsheet form:

Because I ended up looking for regional variations, I coded the column just to the right of my source indicators for the potential geographic bias of the data, if I could perceive one. (1-US, 2-UK, 3-NZ, 4-AU.) If I wasn't sure, I left the column blank. (Fournier & Fournier sometimes got coded as 3-NZ—when the data matched what I found in a New Zealand breeders' association. Sometimes I could tell where Wikipedia's information had been drawn from. In this case, the Oklahoma site referred specifically to Australian sources.)

While Cormo was one of the simplest breeds to come to conclusions about, you'll note discrepancies in the collected numbers.

In staple length, the two sources I found said 2.5 to 4 inches OR 4 to 5 inches. Well, 4 inches seemed like a safe place to land, but there will always be some variety in a natural item like wool. I knew from experience that not every Cormo fleece is exactly 4 inches long.

Staple length can be defined either as "how much wool can these sheep grow in a year?" or as "how long was the wool that the shearer clipped off?" They're not the same. Which were people talking about?

Suspending judgment temporarily, I simply moved to other parts of the summary to see what I could learn.

In fiber diameter, I found additional intriguing oddities. Initially, the numbers looked pretty consistent at 17 to 23 microns, with 21 to 23 microns coming from In Sheep's Clothing (Fournier & Fournier), possibly a reflection of the authors' New Zealand origins. (The breed developed in Australia, but there might be more focused goals among New Zealand breeders. Or not. This was part of my discovery path.)

Turning to ASI, which is the American Sheep Industry Association, I found an even more arresting set of numbers. These were at cross-purposes to each other. This source specified both 17 to 23 microns AND 46s to 56s USDA grades. The micron equivalents of USDA 46s to 56s are 26.4 to 32.7. The site did helpfully specify that it was looking at American Cormo, which might mean it was recording information on a regional variation, even though with this breed the standards appeared to be both strict and internationally consistent.

Fournier & Fournier, with their 21 to 23 microns, in addition specified 64s to 58s. They didn't say whether this was Bradford or USDA, but in either case a ballpark equivalency would be 21 to 27 microns. The grades corresponding to 21 to 23 microns would instead be roughly 64s to 62s, a much narrower span.

I'm skipping lightly here over a discussion of how Bradford numbers differ from USDA grades. We did talk about that in the book. By the way, I constructed the chart comparing fiber counts and USDA grades that appears on pages 12 and 13 of The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook to help myself keep track of all this stuff.

Now, without having resolved anything, I turned to fleece weights. As an initial observation, rams and ewes tend to produce different amounts; rams grow heavier fleeces. Yet a lot more ewes are kept and shorn, so sometimes fleece-weight numbers ignore the rams. Like staple lengths, fleece weights are subject to a lot of interpretation, because the parameters aren't specified. In addition to "ram or ewe?" there's "a full year's maximum growth?" and "skirted, or not?"

The general assumption is that a fleece weight will be grease, not clean; a full year's growth; from a ewe; probably lightly skirted.

But you never know whether that is the case for a particular set of numbers unless it's spelled out.

Where my chart says (e), that means the source specified that this was the weight of ewes' fleeces. (Similarly, some of my charts have both (r) and (e) measurements.)

The Cormo Sheep Conservation Registry liked 12 pounds as a nice, single number, presumably an average. Fournier and Fournier were in the same vicinity, with 9 to 12 pounds. ASI thought fleeces from this breed would be a good deal lighter, 5 to 8 pounds, but they also specified that they were talking about ewes.

When I did my research on Cormos, I did not find micron counts or fleece weights on the Cormo Sheep Conservation Registry website, which is now listing 21 to 23 microns and 5.5 to 12 pounds.

Okay, what to do with all these flying numbers?

At this point, I began to draw pictures.

When I first felt backed into one of these corners, I was on a retreat in Salida, Colorado. This was fortunate, because my retreat times gave me opportunities to stick with one thorny issue or another until I had resolved it, something that wasn't anywhere near as easy when I was home and juggling writing tasks with regular duties and interruptions.

I remember the morning I stared at a sheet of statistics that were not coalescing. I felt compelled to confront the problem with a pencil and some graph paper. I took a brain-clearing walk to the office supplies store and splurged on a spatious pad of quadrille paper, 11 x 17 inches of open territory on each sheet. Back at the cottage, I wrote reference numbers across the long side of one sheet and then sketched where all my different sources thought a particular breed's wool should be (I may have started with the Romneys).

This turned out to be a breakthrough. During my retreat time, I hand-wrote a number of these sheets and refined my system. When I got back to my home computer (and its printer), I made up an Illustrator file with the key across the top and lots of guidelines, like my quadrille paper, in the body of my form. I printed out blanks and used them the same way that I had the big sheets. With pencil. These got tucked into my blue pocket file, either alphabetically by breed or, when I was looking for patterns in particular groups, in clusters by family or fiber type.

The top row of numbers represents micron counts, in crisp, even numbers. Next comes the Bradford scale, and below that the micron counts broken into fragments (with standard deviations) assigned to Bradford-like numbers when the USDA grades were established. Below that, there are the traditional fine/medium/coarse/very coarse designations, and the bottom row relates all the other measurement methods to the old blood system.

What I ended up with for Cormo, as my final numbers to go in the book's box of data:

Staple lengths: 3.25 to 5 inches

Fiber diameters: 17 to 23 microns (in the realm of spinning counts 62s to 80s)

Fleece weights: 5 to 12 pounds

I'm sure some Cormo fleeces are as short as 2.5 inches, but the wonkiness in the ASI wool grades made me mistrust that low end. Of the Cormo wool I've seen, the 4- to 5-inch range seems typical, although some has been shorter.

It seems clear that 21 to 23 microns is where the breeders would like the wool to be. It also seems likely that some may be as fine as 17 microns.

Because of the difficulty of confirming Bradford versus USDA throughout the entire inquiry, and because many people are familiar with those methods of describing fiber diameters, we supplemented the micron counts for fiber diameter with what we called spinning counts, meant to communicate in terms similar to those of the two closely related older systems.

For this breed, one developed at a time when micrometer measurements were coming into fashion and one that is defined in part in terms of the micron counts of its wool growth, I gave more weight to the ranges in microns than to the USDA-Bradford-style numbers that were causing problems. In order to get our "spinning counts," I translated from the micron measurements, coming up with 62s for the 23-micron end of the range and 80s for the 17-micron end. It seems pretty clear that most of the wool will be 21 to 23 microns, or 64s to 62s, but we couldn't write a whole essay like this about every breed.

I settled on a range of 5 to 12 pounds to take into account the span from what was probably a light ewe fleece to what was likely a heavy ram fleece.

Wool is a natural, not manufactured, material. It will always have variability—more than anyone coming newly to the topic of studying it can begin to imagine. Getting more precise numbers would require a dedicated research project for each breed (with an extensive budget for communication with breeders, likely including travel, as well as sampling and analysis). The end results would not serve our intended purpose any better than what I'd done.

___

Having wrestled a clutter numbers to a ground of my own defining, I would let myself spin some samples, as a reminder of what it was all about: a person, at a wheel, with some fiber, enjoying the process of making yarn.

And that's enough for one day. I'll continue later.

Spinning photo taken on a writing/research/spinning retreat in the mountains of Colorado, March 2009. Photo by writing friend Judy Fort Brenneman.

_____________________________________________________

Information and new sources continue to appear. Here are a couple of items that would have fed into my research, except that they appeared after I had to call it quits and give the manuscript to the publisher. (We tweaked until the last minute, but couldn't continue the fundamental heavy lifting for that long.) First there's an article with great quotes from Ian Downie, who developed the Cormo breed. Second, a new registry was established in 2009, also too late for inclusion.

The new Cormo Breeders Coalition has this to say about the wool: "Sample from mid-side 17–23 micron. Consistent wool with 90% of wool within a two micron range. Staple length 3.5" to 5.5". Dense soft wool. Fleece weight mature ewe 5–8 lbs." Add this set of numbers to my list.

There's always more to be discovered! Sometimes those discoveries will result in corrections to previous conclusions. In this case, I read that and said, "So far, so good for my conclusions on that breed."

January 17, 2012

Scrivener and the Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook

—> Long post warning

Before I launch into a fairly technical discussion, I want to mention one of the things that makes it all worthwhile. This week's Spinning Daily newsletter shows what Betsy Alspach did following the SOAR workshop that she took with me this past October. Thanks to Betsy for continuing her enjoyment of the fibers we played with; for making her magic skein; and for sharing it and the story. Click the image to read the whole article online.

_____

The nitty-gritty

I've been researching and exploring new software solutions. As I do so, I would like to shine a spotlight on a piece of software that I came across by accident, as a result of a series of computer disasters. I treasure it. It is, and will continue to be, key to my work.

When I began research for The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, I employed PCs running Windows XP and, the primary machine for that project, a laptop running Linux. I organized my research in traditional computer folders. The method was cumbersome, but familiar. I did a lot of tedious keyboard work—for example, making notes from websites—while remembering, and being glad to be past, the days of writing longhand on index cards.

About that time, the PCs started not playing nicely and I lost about two years' worth of income-producing work: not because my hard drive crashed or my files were lost, but because all my time (and a lot of money, hiring consultants) was spent trying to get the PCs to let me get something accomplished other than talking to tech support.

Cutting to the chase, after waiting far longer than I should have (because although the solution cost a lot, so did the troubleshooting), I ditched all but one of the PCs, bought a couple of Macs, and . . . discovered

I like Scrivener so well that even though time now is short, I opened up Illustrator and played with some type in a garish display of enthusiasm. (That's P22 Vale Pro, a dignified face that I've abused amused(?) with an array of colors.)

In 2011, a version of Scrivener became available for PCs; in 2008, it was Mac-only. If I'd known about it, I would have figured out how to buy a Mac just to run it. Wow, did it make my life easier for the extended, focused, broad-based, complex project that became The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook. I'm not sure who told me about Scrivener: my niece, Corey, or my daughter's best friend, Jenny, or both. They, and the program, saved whatever shreds of sanity I had left after the PC nightmares.

This will be a nuts-and-bolts post about organization and process. Keep in mind that I was using an earlier version of Scrivener. I've upgraded, but I haven't implemented any new tricks in this legacy file. I also didn't master all of the software's capacities in the version I used then. I didn't have to. Without asking a lot of me, Scrivener provided a flexible, friendly, reliable foundation for a huge project.

_____

The Scrivener screenshots should be clickable for larger versions. I generally try to keep my images small, but because some people may want to see more detail and I still don't want to hog bandwidth for my friends who are on dial-up (yes, some are), I'm trying something new.

_____

Moving into Scrivener

I'll start with my overall organizational scheme. I'll drill down into it, then back up to show part of my working process. The entire process would require another book to explain. . . . I hope that what I'm presenting here is helpful and clear.

Keep in mind that you're seeing the final working file. It evolved over several years and through many iterations. Scrivener is so accommodating that way. I would save a snapshot (so I could go back, if I needed to), move things around, and keep making forward progress as I did so. I never did have to go back to a saved version. And I should mention that one of the things I like about Scrivener is that everything in it can be accessed without the program, should computer disasters occur. I don't find a link explaining that detail right now, but I remember it clearly. Scrivener's storage methods are not proprietary.

I started by importing my existing PC folders full of files into Scrivener, which was easy, even though there were heaps of them. Then I started arranging and rearranging, as well as continuing with my research and doing things I couldn't do before—like importing web pages instead of re-keying the pertinent bits.

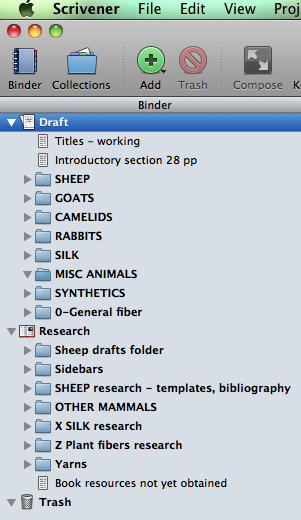

The Draft folder: overall conceptual framework and a container for final files

In Scrivener, a Draft folder can contain only text, not images or other miscellaneous file types. So I used that top, Draft section for an overview of where we were going, and then as a container for final files. The heavy lifting took place in the Research folder.

This is the big picture, the view from space. Within each folder, we estimated the components' final page counts. The associated file for each family or group sketched out how we intended to use those pages. The allocations changed, of course, but you see the "introductory section" above was scheduled for about 28 pages.

I also ultimately made a second Scrivener project file for Fleece & Fiber. The original project collection ended up being dedicated to the sheep, with cross-references to the second file for all the other animals and the peripheral research (synthetics, silk, and plants). I did keep the old folders in the original file, mostly because I didn't need to take them out (speed, speed . . . ).

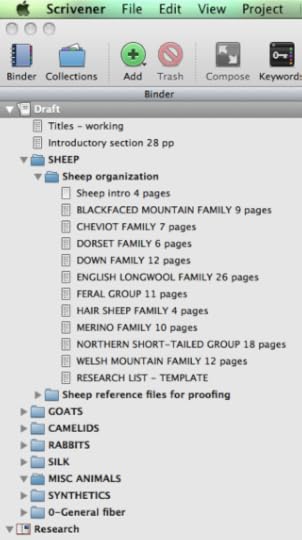

Here's the breakdown for the sheep section:

At the bottom of the sheep folder, there's a subfolder called "Sheep reference files for proofing," which contained the text-only versions that we compiled into the final manuscript. I worked FROM this area in Research down into the Draft folder, and then brought my finished work back up here.

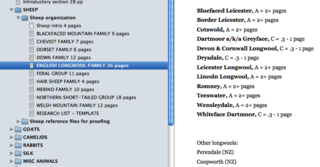

The next view shows both the organizing pane on the left and a portion of one of the component files in the window on the right. I've highlighted the file for the English Longwool family. At the right, you can see what breeds we planned to include in this section and the estimated number of pages for each (the bottom showing some of the other breeds we needed to keep in mind as we prepared this section, even though they aren't English Longwools):

A good six months' worth of work preceded the establishment of these folders, during which co-author Carol Ekarius and I went back and forth through e-mail, Skype, and in-person meetings about what would be included and how we would organize it. That's where the "family" and "group" units originated. Sheep breeds can be sorted and associated with each other in infinite numbers of ways. Our final method balanced my fiber-related wish list with Carol's livestock-focused perspective.

I haven't checked yet to see how closely the finished book conforms to the listed page-count targets. Everything changed constantly as we proceeded. (Silk and synthetics obviously weren't part of the scope of our finished work. We pulled them out in the interest of completing the book before the turn of the 22nd century.)

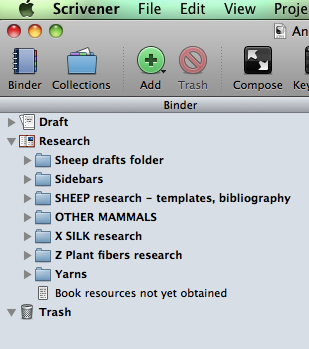

The Research folder: where I lived

Unhampered by the sensible yet strict limitations of the Draft section, a Scrivener project's Research area can contain many types of files: text, images, imported web pages. . . . Because of its flexibility, the research section of the Fleece & Fiber projects (numbers 1 & 2) became my electronic home for several years.

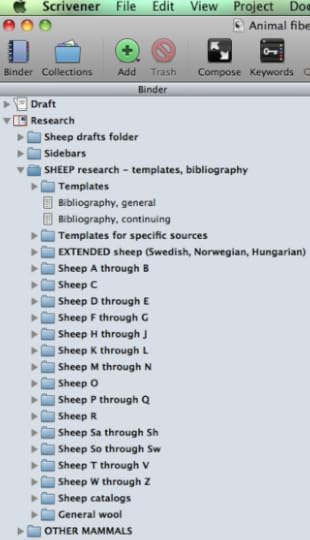

Here is the highest-level view of the sheep-corral Scrivener project, with the research subfolders revealed. It's deceptively (and comfortingly) simple.

Yarns contained details about potential sources for sample yarns (as opposed to fibers). That was mostly Carol's department, although when I came across options while I was doing other research, I'd make notes here and then tell her about them.

I'm going to demo with the SHEEP research.

To make the second project for the OTHER MAMMALS, I copied the original all-encompassing file, renamed it, and deleted all the sheep info from that copy. The X and Z codes in the folder names are my signals that this is information peripheral to the current project, although it's stuff I want to keep track of.

Going deeper into research

Now we begin to get serious. Here's the next level of files and folders under SHEEP research:

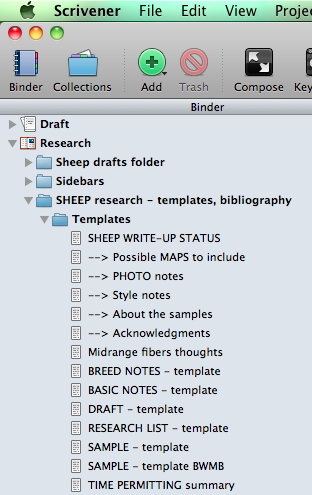

At the top are templates that I used for specific types of files, and a couple of running bibliography files. Scrivener now has (and may have had then) better ways to manage templates and bibliographies. My manually implemented methods worked fine, although I pushed the limits of practicality. For the next big project (she says, with trepidation), I'll do more with templates and corkboards. I really didn't need them this time.

Here's a quick side trip to see the contents of my templates folder:

Back to the main tour.

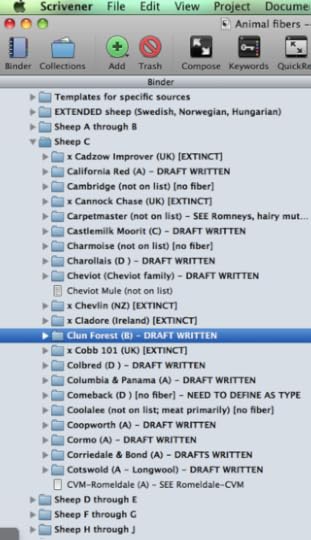

I organized the sheep breeds (and types) alphabetically in subfolders. Initially the folders encompassed larger chunks of the alphabet, say A through F. As time went on, I had to slice more finely. The S breeds ultimately needed two folders!

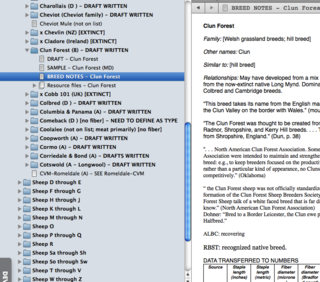

Here's the C folder, which I'll use for the demo because there were enough breeds to make a one-letter group but not so many I can't get them into a screenshot of reasonable size.

My comprehensive list included breeds that were mentioned in sources I consulted but that have become extinct. (The x in front of the name reminded me not to pay too much attention once I had resolved the breed's status: having these records within the file was useful when I was tracing the development of other breeds that still exist.)

A few of the breeds in that list did not end up in the finished book because we ran out of time. If we had fiber, we fit the breed in. If not, we were forced to let some go. We discussed mules as a category (for example, Cheviot Mule), but mules are crossbreds so the many types of mules didn't get individual treatment.

There are also cross-references in this list. CVM ended up being filed under R for Romeldale, because CVM is currently being treated as a specific type of Romeldale and not as a separate breed (there was a time when it was classed differently). To keep myself from wondering whether I'd lost my CVM notes, I made a blank file to tell me where I'd put them.

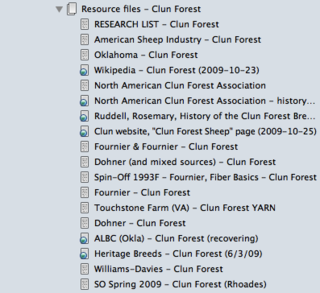

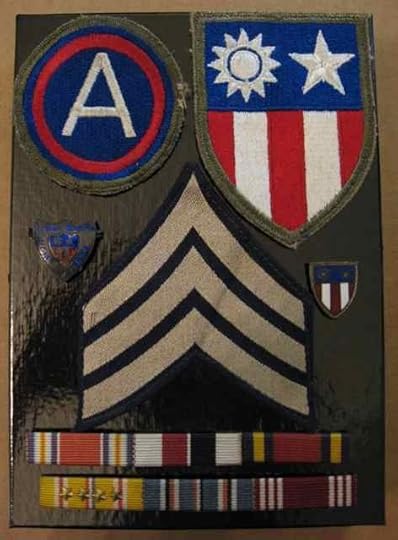

Clun Forest is highlighted in the screenshot because I'm going to use it as my example in drilling down farther. Within the Clun Forest folder, which is shown in its finished form, are the DRAFT (working text), a SAMPLE (spinning notes), BREED NOTES, which contained my summary of my research, which is in the stack (rather than folder) of Resource files. The files within the folder progress, in level of completion, from bottom to top:

resources (research) —> notes (summarizing) —> sample(s) (spinning) —> draft (writing).

All of the files and folders contain the breed name, so if things got out of order I could put them back. Items moved constantly as I was working, and this naming convention served as a safety net. I added notes to the FOLDER names about the level of completion for that breed, so I didn't have to open the folders to see where I needed to turn my attention next.

EVERY BREED had a set of files that looked like these. Many sets were much more extensive.

The Resource files got the major action at the start.

I had a template file that stayed at the top of the resource pile called RESEARCH LIST. It summarized the basic resources that I wanted to be sure I checked for each breed. If there was no information on the breed in that resource, I'd mark "none" so I'd remember that I'd already done it. For example, there are no notes for the Clun Forest from Ryder (Sheep and Man). Because Ryder was a primary resource that I was unlikely to skip, yet the information in it is diffuse and requires time to assemble, I might think this was an oversight. I could check my research list and discover it wasn't. From here on, the screenshots show the folder organization on the left and part of the view of the highlighted file itself on the right. Scrivener, of course, has a larger screen area and shows more of the file. I've just cropped my images to keep this discussion as nimble as possible.

I had, indeed, checked Ryder. Yes, he had something to say about Clun Forests, but not enough to warrant a whole file of notes. (Often my Ryder notes were extensive.) On the summary page, I recorded page numbers and topics, in case I needed to retrieve a specific piece of information later.

"Dohner (and mixed sources)" above means that this was an imported file from early research and I'd keyed information from several locations into a single file. Once I was in Scrivener, I did separate out the Dohner portion, because the book (Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds) was one of my most important sources. (There's an individual file for it later in the list.) (Scrivener handles multiple files much better than my old C:/sheep folder did, and lets me look at the contents, not just guess at them based on the cryptic names I've given them. Oh, and its search functions are superb!)

The point was not to maintain the system perfectly but to set up scaffolding strong enough to support the bigger tasks of research and writing.

Once I had completed the review of resources, I compiled BREED NOTES into which I cut and pasted (or typed my comments about) the highlights from my searches. This file consisted of quotes and summaries, and is what I put in front of me when I actually started to write (using Scrivener's split-screen function, also a boon at many other times).

See the note about "Data transferred to Numbers" at the bottom of the righthand pane? While Scrivener doesn't handle spreadsheet information especially well, I managed to put some spreadsheets into my BREED NOTES files and to manipulate some data there. I supported this with Numbers (Mac spreadsheet) files; that's part of the "how did I come up with the numbers?" discussion. (Another idea on my list of topics to write about here is how I decided what numbers to put in the breed data boxes for The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook.But that wasn't a Scrivener task.)

When I spun fiber from the breed, I made succinct notes about the samples, the tools and techniques I used, and my subjective impressions. I kept a number of the variables standardized, for speed and ease of record-keeping, so those items aren't in the notes. Unless otherwise specified, I used a Lendrum folding wheel with a standard flyer, on its highest-speed whorl.

For some breeds, I made a lot of samples. I chose Clun Forest for this demo because it has all the necessary parts but was not complicated. Each SAMPLE file refers to one source or color of fiber—i.e., one fleece or batch. If I made more than one skein from the same wool, all my experiments are in the same file. (My sample notes are backed up by a separate database (print and electronic) of the fibers we obtained, where they came from, and what they were like. There's enough information here—Hagerstown, MD—for me to locate more detailed background on this wool.)

Finally, I would write. That step occurred in a DRAFT file (still in the Research section, not the Draft section).

When I finished, I would send a copy of that file to Carol, because this was the point at which our writing process became collaborative.

When I sent Carol a file, I marked its status in another Scrivener record I made up to track where we were in our final coordination on each breed, because we sure didn't work in lockstep—as individuals or as a team—from page 1 to the final page! Our major collaborative activities occurred at the beginning of Fleece & Fiber, with a determination of what we would cover and how it would be organized, and at the end, when we blended our contributions into what we think, and hope, is a seamless whole. In between, we kicked ideas and tasks back and forth as needed, but worked independently for the most part.

I put this tracking file under "Templates," back up at the top of the Research folder so I could find it easily.

I still kept within this list the names of breeds and types that we were not covering. Having that information readily available saved time and sanity. In an undertaking of this size, the less time you spend hunting for or wondering about things, the better.

At the bottom of the Templates group, you'll see a TIME PERMITTING summary. This was a place for me to note tasks I'd thought of to do, if we had time: additional types of samples to spin from specific fibers I'd had to set aside in order to move to the next; sidebars we might have written if we had possessed infinite time and could have printed infinite numbers of pages; and so on. I did complete the most important tasks on the list.

And there is, of course, the whole second Scrivener project file for the Other Mammals, which ended up including the EXTENDED sheep as well.

_____

Scrivener, my stalwart companion, has requested some software allies

Scrivener is an amazing tool for organizing and writing a massive project. Carol and I also used a lot of spreadsheets. The array sufficed. We made it.

So why am I looking at other software solutions?

I'm asking Scrivener to do jobs it wasn't designed for. It's been doing them exceptionally well to date, but I need to reserve it for what it's best at: organizing and facilitating writing projects, large and small.

Scrivener is fantastic when you know what you want to do. There are other tools that will work better for the amorphous, preparatory stages, and for managing information that may be used in multiple projects, not yet defined. It's also been fine for organizing workshops so far—planning, tracking details, and putting together the materials and handouts—but as I teach more workshops, I need to quit asking Scrivener to bend over backward for me.

I need to supplement Scrivener with a DATABASE to track fibers, yarns, and workshop information. I need a dedicated BIBLIOGRAPHIC system. I need a way to save, sort, organize, and OCR the PDFs and notes I'm gathering, even though I'm not sure which project or projects I'll need them for. And I need a flexible technique for gathering and moving my ideas around before they've become projects, so I can see how my coming-into-focus thoughts relate to each other (by means of a tool that won't let my ponderings get crumpled up and lost in a pile of papers).

I'm currently beginning to learn:

Database: Bento (the learning curve and price are appealing, and it already seems helpful)

Bibliographic system: Bookends (coming along nicely, although I'm not yet sure how it will connect to the other software—actually, the matter of connection is a question I have about everything I'm doing)

Collecting and organizing research: DevonThink (I have it, and have read the Take Control book and a bunch of stuff on the forums)

Ideas: TinderBox (I have it, and have read a bunch on the forums and have loaded the tutorials onto my computer)

This is going to take a while. Researching, trying out, deciding on, and investing in the tools has taken about a year. Now I need to get conversant enough with them to entrust them with parts of my workflow. I also have deadlines, which would be easier to meet if I had the new systems in place. Yet the time I can dedicate to learning them is limited.

Onward. The eternal balancing act.

_____

I know this: Scrivener is solid. Even though I've discovered I can't do everything with it, I can do amazing amounts. It's gotten me this far. And Scrivener is a tool that makes work fun.

Scrivener and the Fleece & FIber Sourcebook

—> Long post warning

Before I launch into a fairly technical discussion, I want to mention one of the things that makes it all worthwhile. This week's Spinning Daily newsletter shows what Betsy Alspach did following the SOAR workshop that she took with me this past October. Thanks to Betsy for continuing her enjoyment of the fibers we played with; for making her magic skein; and for sharing it and the story. Click the image to read the whole article online.

_____

The nitty-gritty

I've been researching and exploring new software solutions. As I do so, I would like to shine a spotlight on a piece of software that I came across by accident, as a result of a series of computer disasters. I treasure it. It is, and will continue to be, key to my work.

When I began research for The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, I employed PCs running Windows XP and, the primary machine for that project, a laptop running Linux. I organized my research in traditional computer folders. The method was cumbersome, but familiar. I did a lot of tedious keyboard work—for example, making notes from websites—while remembering, and being glad to be past, the days of writing longhand on index cards.

About that time, the PCs started not playing nicely and I lost about two years' worth of income-producing work: not because my hard drive crashed or my files were lost, but because all my time (and a lot of money, hiring consultants) was spent trying to get the PCs to let me get something accomplished other than talking to tech support.

Cutting to the chase, after waiting far longer than I should have (because although the solution cost a lot, so did the troubleshooting), I ditched all but one of the PCs, bought a couple of Macs, and . . . discovered

I like Scrivener so well that even though time now is short, I opened up Illustrator and played with some type in a garish display of enthusiasm. (That's P22 Vale Pro, a dignified face that I've abused amused(?) with an array of colors.)

In 2011, a version of Scrivener became available for PCs; in 2008, it was Mac-only. If I'd known about it, I would have figured out how to buy a Mac just to run it. Wow, did it make my life easier for the extended, focused, broad-based, complex project that became The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook. I'm not sure who told me about Scrivener: my niece, Corey, or my daughter's best friend, Jenny, or both. They, and the program, saved whatever shreds of sanity I had left after the PC nightmares.

This will be a nuts-and-bolts post about organization and process. Keep in mind that I was using an earlier version of Scrivener. I've upgraded, but I haven't implemented any new tricks in this legacy file. I also didn't master all of the software's capacities in the version I used then. I didn't have to. Without asking a lot of me, Scrivener provided a flexible, friendly, reliable foundation for a huge project.

_____

The Scrivener screenshots should be clickable for larger versions. I generally try to keep my images small, but because some people may want to see more detail and I still don't want to hog bandwidth for my friends who are on dial-up (yes, some are), I'm trying something new.

_____

Moving into Scrivener

I'll start with my overall organizational scheme. I'll drill down into it, then back up to show part of my working process. The entire process would require another book to explain. . . . I hope that what I'm presenting here is helpful and clear.

Keep in mind that you're seeing the final working file. It evolved over several years and through many iterations. Scrivener is so accommodating that way. I would save a snapshot (so I could go back, if I needed to), move things around, and keep making forward progress as I did so. I never did have to go back to a saved version. And I should mention that one of the things I like about Scrivener is that everything in it can be accessed without the program, should computer disasters occur. I don't find a link explaining that detail right now, but I remember it clearly. Scrivener's storage methods are not proprietary.

I started by importing my existing PC folders full of files into Scrivener, which was easy, even though there were heaps of them. Then I started arranging and rearranging, as well as continuing with my research and doing things I couldn't do before—like importing web pages instead of re-keying the pertinent bits.

The Draft folder: overall conceptual framework and a container for final files

In Scrivener, a Draft folder can contain only text, not images or other miscellaneous file types. So I used that top, Draft section for an overview of where we were going, and then as a container for final files. The heavy lifting took place in the Research folder.

This is the big picture, the view from space. Within each folder, we estimated the components' final page counts. The associated file for each family or group sketched out how we intended to use those pages. The allocations changed, of course, but you see the "introductory section" above was scheduled for about 28 pages.

I also ultimately made a second Scrivener project file for Fleece & Fiber. The original project collection ended up being dedicated to the sheep, with cross-references to the second file for all the other animals and the peripheral research (synthetics, silk, and plants). I did keep the old folders in the original file, mostly because I didn't need to take them out (speed, speed . . . ).

Here's the breakdown for the sheep section:

At the bottom of the sheep folder, there's a subfolder called "Sheep reference files for proofing," which contained the text-only versions that we compiled into the final manuscript. I worked FROM this area in Research down into the Draft folder, and then brought my finished work back up here.

The next view shows both the organizing pane on the left and a portion of one of the component files in the window on the right. I've highlighted the file for the English Longwool family. At the right, you can see what breeds we planned to include in this section and the estimated number of pages for each (the bottom showing some of the other breeds we needed to keep in mind as we prepared this section, even though they aren't English Longwools):

A good six months' worth of work preceded the establishment of these folders, during which co-author Carol Ekarius and I went back and forth through e-mail, Skype, and in-person meetings about what would be included and how we would organize it. That's where the "family" and "group" units originated. Sheep breeds can be sorted and associated with each other in infinite numbers of ways. Our final method balanced my fiber-related wish list with Carol's livestock-focused perspective.

I haven't checked yet to see how closely the finished book conforms to the listed page-count targets. Everything changed constantly as we proceeded. (Silk and synthetics obviously weren't part of the scope of our finished work. We pulled them out in the interest of completing the book before the turn of the 22nd century.)

The Research folder: where I lived

Unhampered by the sensible yet strict limitations of the Draft section, a Scrivener project's Research area can contain many types of files: text, images, imported web pages. . . . Because of its flexibility, the research section of the Fleece & Fiber projects (numbers 1 & 2) became my electronic home for several years.

Here is the highest-level view of the sheep-corral Scrivener project, with the research subfolders revealed. It's deceptively (and comfortingly) simple.

Yarns contained details about potential sources for sample yarns (as opposed to fibers). That was mostly Carol's department, although when I came across options while I was doing other research, I'd make notes here and then tell her about them.

I'm going to demo with the SHEEP research.

To make the second project for the OTHER MAMMALS, I copied the original all-encompassing file, renamed it, and deleted all the sheep info from that copy. The X and Z codes in the folder names are my signals that this is information peripheral to the current project, although it's stuff I want to keep track of.

Going deeper into research

Now we begin to get serious. Here's the next level of files and folders under SHEEP research:

At the top are templates that I used for specific types of files, and a couple of running bibliography files. Scrivener now has (and may have had then) better ways to manage templates and bibliographies. My manually implemented methods worked fine, although I pushed the limits of practicality. For the next big project (she says, with trepidation), I'll do more with templates and corkboards. I really didn't need them this time.

Here's a quick side trip to see the contents of my templates folder:

Back to the main tour.

I organized the sheep breeds (and types) alphabetically in subfolders. Initially the folders encompassed larger chunks of the alphabet, say A through F. As time went on, I had to slice more finely. The S breeds ultimately needed two folders!

Here's the C folder, which I'll use for the demo because there were enough breeds to make a one-letter group but not so many I can't get them into a screenshot of reasonable size.

My comprehensive list included breeds that were mentioned in sources I consulted but that have become extinct. (The x in front of the name reminded me not to pay too much attention once I had resolved the breed's status: having these records within the file was useful when I was tracing the development of other breeds that still exist.)

A few of the breeds in that list did not end up in the finished book because we ran out of time. If we had fiber, we fit the breed in. If not, we were forced to let some go. We discussed mules as a category (for example, Cheviot Mule), but mules are crossbreds so the many types of mules didn't get individual treatment.

There are also cross-references in this list. CVM ended up being filed under R for Romeldale, because CVM is currently being treated as a specific type of Romeldale and not as a separate breed (there was a time when it was classed differently). To keep myself from wondering whether I'd lost my CVM notes, I made a blank file to tell me where I'd put them.

Clun Forest is highlighted in the screenshot because I'm going to use it as my example in drilling down farther. Within the Clun Forest folder, which is shown in its finished form, are the DRAFT (working text), a SAMPLE (spinning notes), BREED NOTES, which contained my summary of my research, which is in the stack (rather than folder) of Resource files. The files within the folder progress, in level of completion, from bottom to top:

resources (research) —> notes (summarizing) —> sample(s) (spinning) —> draft (writing).

All of the files and folders contain the breed name, so if things got out of order I could put them back. Items moved constantly as I was working, and this naming convention served as a safety net. I added notes to the FOLDER names about the level of completion for that breed, so I didn't have to open the folders to see where I needed to turn my attention next.

EVERY BREED had a set of files that looked like these. Many sets were much more extensive.

The Resource files got the major action at the start.

I had a template file that stayed at the top of the resource pile called RESEARCH LIST. It summarized the basic resources that I wanted to be sure I checked for each breed. If there was no information on the breed in that resource, I'd mark "none" so I'd remember that I'd already done it. For example, there are no notes for the Clun Forest from Ryder (Sheep and Man). Because Ryder was a primary resource that I was unlikely to skip, yet the information in it is diffuse and requires time to assemble, I might think this was an oversight. I could check my research list and discover it wasn't. From here on, the screenshots show the folder organization on the left and part of the view of the highlighted file itself on the right. Scrivener, of course, has a larger screen area and shows more of the file. I've just cropped my images to keep this discussion as nimble as possible.

I had, indeed, checked Ryder. Yes, he had something to say about Clun Forests, but not enough to warrant a whole file of notes. (Often my Ryder notes were extensive.) On the summary page, I recorded page numbers and topics, in case I needed to retrieve a specific piece of information later.

"Dohner (and mixed sources)" above means that this was an imported file from early research and I'd keyed information from several locations into a single file. Once I was in Scrivener, I did separate out the Dohner portion, because the book (Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds) was one of my most important sources. (There's an individual file for it later in the list.) (Scrivener handles multiple files much better than my old C:/sheep folder did, and lets me look at the contents, not just guess at them based on the cryptic names I've given them. Oh, and its search functions are superb!)

The point was not to maintain the system perfectly but to set up scaffolding strong enough to support the bigger tasks of research and writing.

Once I had completed the review of resources, I compiled BREED NOTES into which I cut and pasted (or typed my comments about) the highlights from my searches. This file consisted of quotes and summaries, and is what I put in front of me when I actually started to write (using Scrivener's split-screen function, also a boon at many other times).

See the note about "Data transferred to Numbers" at the bottom of the righthand pane? While Scrivener doesn't handle spreadsheet information especially well, I managed to put some spreadsheets into my BREED NOTES files and to manipulate some data there. I supported this with Numbers (Mac spreadsheet) files; that's part of the "how did I come up with the numbers?" discussion. (Another idea on my list of topics to write about here is how I decided what numbers to put in the breed data boxes for The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook.But that wasn't a Scrivener task.)

When I spun fiber from the breed, I made succinct notes about the samples, the tools and techniques I used, and my subjective impressions. I kept a number of the variables standardized, for speed and ease of record-keeping, so those items aren't in the notes. Unless otherwise specified, I used a Lendrum folding wheel with a standard flyer, on its highest-speed whorl.

For some breeds, I made a lot of samples. I chose Clun Forest for this demo because it has all the necessary parts but was not complicated. Each SAMPLE file refers to one source or color of fiber—i.e., one fleece or batch. If I made more than one skein from the same wool, all my experiments are in the same file. (My sample notes are backed up by a separate database (print and electronic) of the fibers we obtained, where they came from, and what they were like. There's enough information here—Hagerstown, MD—for me to locate more detailed background on this wool.)

Finally, I would write. That step occurred in a DRAFT file (still in the Research section, not the Draft section).

When I finished, I would send a copy of that file to Carol, because this was the point at which our writing process became collaborative.

When I sent Carol a file, I marked its status in another Scrivener record I made up to track where we were in our final coordination on each breed, because we sure didn't work in lockstep—as individuals or as a team—from page 1 to the final page! Our major collaborative activities occurred at the beginning of Fleece & Fiber, with a determination of what we would cover and how it would be organized, and at the end, when we blended our contributions into what we think, and hope, is a seamless whole. In between, we kicked ideas and tasks back and forth as needed, but worked independently for the most part.

I put this tracking file under "Templates," back up at the top of the Research folder so I could find it easily.

I still kept within this list the names of breeds and types that we were not covering. Having that information readily available saved time and sanity. In an undertaking of this size, the less time you spend hunting for or wondering about things, the better.

At the bottom of the Templates group, you'll see a TIME PERMITTING summary. This was a place for me to note tasks I'd thought of to do, if we had time: additional types of samples to spin from specific fibers I'd had to set aside in order to move to the next; sidebars we might have written if we had possessed infinite time and could have printed infinite numbers of pages; and so on. I did complete the most important tasks on the list.

And there is, of course, the whole second Scrivener project file for the Other Mammals, which ended up including the EXTENDED sheep as well.

_____

Scrivener, my stalwart companion, has requested some software allies

Scrivener is an amazing tool for organizing and writing a massive project. Carol and I also used a lot of spreadsheets. The array sufficed. We made it.

So why am I looking at other software solutions?

I'm asking Scrivener to do jobs it wasn't designed for. It's been doing them exceptionally well to date, but I need to reserve it for what it's best at: organizing and facilitating writing projects, large and small.

Scrivener is fantastic when you know what you want to do. There are other tools that will work better for the amorphous, preparatory stages, and for managing information that may be used in multiple projects, not yet defined. It's also been fine for organizing workshops so far—planning, tracking details, and putting together the materials and handouts—but as I teach more workshops, I need to quit asking Scrivener to bend over backward for me.

I need to supplement Scrivener with a DATABASE to track fibers, yarns, and workshop information. I need a dedicated BIBLIOGRAPHIC system. I need a way to save, sort, organize, and OCR the PDFs and notes I'm gathering, even though I'm not sure which project or projects I'll need them for. And I need a flexible technique for gathering and moving my ideas around before they've become projects, so I can see how my coming-into-focus thoughts relate to each other (by means of a tool that won't let my ponderings get crumpled up and lost in a pile of papers).

I'm currently beginning to learn:

Database: Bento (the learning curve and price are appealing, and it already seems helpful)

Bibliographic system: Bookends (coming along nicely, although I'm not yet sure how it will connect to the other software—actually, the matter of connection is a question I have about everything I'm doing)

Collecting and organizing research: DevonThink (I have it, and have read the Take Control book and a bunch of stuff on the forums)

Ideas: TinderBox (I have it, and have read a bunch on the forums and have loaded the tutorials onto my computer)

This is going to take a while. Researching, trying out, deciding on, and investing in the tools has taken about a year. Now I need to get conversant enough with them to entrust them with parts of my workflow. I also have deadlines, which would be easier to meet if I had the new systems in place. Yet the time I can dedicate to learning them is limited.

Onward. The eternal balancing act.

_____

I know this: Scrivener is solid. Even though I've discovered I can't do everything with it, I can do amazing amounts. It's gotten me this far. And Scrivener is a tool that makes work fun.

January 12, 2012

Choosing the breeds for Explore 4

For the survey classes on wools that I teach (on both general breed-specific wools and rare-breed wools), I aim to have a variety of types of sheep represented in the fibers I collect to share with people. The final line-up always involves an interesting balancing act, limited by what's available when the fiber-gathering takes place:

representing different parts of the available fiber world (geographically speaking)

long / short

crimpy / wavy / straight

supple / sturdy

matte / shiny

single-coated / diverse fiber mix

butter-soft / warmly lofty, and, for fun,

in different colors

Choosing and acquiring the four breeds for the Explore 4 workshop that I'll be teaching in March, where we will focus on a single breed each day, has required the same careful assessment of which will complement each other in ways both obvious and subtle. In this case, I need to cover the broad set of bases with a handful of choices.

It's been a fun challenge, and as of yesterday I've lined up the crew! I've got my breeds, and I've also got the specific fleeces, selected for qualities like individual character and color.

Now—because this is the way I work, with the fiber we'll have in our hands preceding everything else—I can start to prepare detailed background information on the breeds. For the survey courses I teach, I already have the materials roughed out and I refine and adjust them when I know which specific breeds will be included. Yet Explore 4 provides a welcome excuse to present even richer stories about these breeds' history and characteristics.

For Explore 4, we'll be getting to know:

Black Welsh Mountain (black, of course),

Leicester Longwool (shiny white and long),

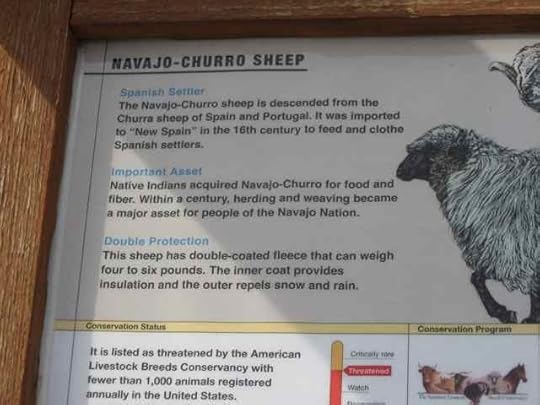

Navajo Churro (this one will be gray), and

Romney (I'm getting a brown one: brown Romneys aren't common, and the breed produces gorgeous shades).

The first three are rare breeds, and the fourth is a classic.

That's a Black Welsh Mountain sheep; I took the photo at the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival a few years ago during the Parade of Breeds. (Last year, my camera wasn't working right and I missed a lot of good pictures, although I have some. I'll be there again this year and will see if I can do better. Same camera, hopefully working more reliably.)

I've already been washing the Leicester Longwool, which I bought at a freeway stop in Oregon last August. (I just needed a few yards of yarn, but I couldn't resist the raw wool.) Isn't it beautiful when it's released from its covering of grease, suint, and garden-variety dirt? The top and bottom in the next photo are the same fleece. All I did was wash it! Yet the luster and potential are clearly evident in the just-shorn state. (Um, the bottom is the clean portion {grin}.)

Speaking of washing, I've been asked to write some background information on how wool gets cleaned for a couple of upcoming online posts on other websites. (I'll try to remember, when these go live, to mention them, either here or on Twitter, where I'm @effortlesszone.)

I do love the transformation that happens in the tub. It's magic. And it's the start of a whole bunch of other magic.

* * * * *

Detail-y stuff, for those who want to know:

I'll be conducting survey workshops—expeditiously covering as many breeds as we can fit into the scheduled hours—at the Madrona Winter Retreat (in Tacoma, Washington) in February, and later in the year at the Maryland Sheep & Wool Festival (schedule not posted as of when I'm writing), Olds College Fibre Week (Canada; registrations open March 1), Convergence 2012 (California; registration open now), and the Weavers Guild of Minnesota (registration open now). I'll also be teaching at The Spinning Loft (Michigan) in the fall, although we haven't decided what topic(s) we'll feature.

In addition, Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook co-author Carol Ekarius and I may be doing a couple of informational programs (not hands-on workshops) together at one 2012 event. We have a good time working together, so we've agreed to see if we can get it onto our schedules. I'll provide details when they're firmed up.

Registration numbers for all my classes and workshops are limited, yet openings do occur—one workshop that sold out on its opening day ended up having a space freed up a couple of months later. It's worth checking back. For all of these workshops, only basic spinning skills and equipment (listed in the descriptions) are necessary. It's all about starting where we are and moving to the next level.

Speaking of moving skills to the next level, I THINK I've figured out how to make the basic information for Explore 4 available here: click to download a PDF about Explore-4_2012. We've got a fantastic group coming together and there are still some spaces available for folks to join in.

* * * * *

All of the photos of wool in this post, from raw to knitted swatch, are Leicester Longwool. I do need to get a good picture of the Leicester Longwool sheep at Maryland! The photo with the skeins shows a couple of handspuns. I knitted the swatch from commercially prepared yarn.

January 5, 2012

Playing with yarn

I'm acquiring and preparing fibers and yarns for upcoming workshops. The amount of up-front work, and its complex nature, is one reason I only accept a small number of teaching opportunities each year. (Over the course of 2012, I'll be teaching in Washington, Maryland, Minnesota, California, Alberta, and Michigan.)

First up is the Madrona Winter Retreat, from February 16 to 19 in Tacoma, Washington. At Madrona, some of my classes have filled, but others have a few openings; there are sessions for both spinners and knitters, as well as for people who are interested in publishing their fiber work. I'll also be doing an informal clinic, and giving a talk on Saturday night at the banquet.

Here's what I've been up to in getting ready for just two of my seven Madrona offerings. These are yarn-based classes (rather than fiber-based ones). One is Understanding Breed-Specific Yarns and the other is Introduction to Rare-Breed Wools.

My first challenge is to determine which breeds will be covered—in other words, what I can find appropriate yarns for. I want to make sure that each class has a variety of types of wools, and, in this case, that the breeds covered in the two classes are all different, in case anyone wants to take both. (There will be no repeated breeds.) Although I ask people to bring a variety of sizes of needles for swatching, I try to find yarns for sampling that are within a fairly narrow range of weights. This can be challenging, because these artisan yarns often only come in one or two weights. I aim for sport or DK, and I settle, when necessary, for worsted or aran.

With one exception, all of the yarns are undyed, because I want to keep the emphasis on the fiber qualities. We are so easily seduced by lovely colors! They can obscure our perceptions of what the fiber itself is like. (The one dyed fiber wasn't available undyed at the moment when I ordered, and I decided I wanted to include it anyway. As it turns out, the dye effect—which happens to be lovely—will offer a chance to include an extra instructional point. It will earn its keep.)

I order the yarns and they start arriving.

I wind skeins into balls.

I go back and forth with one producer about what's been happening with her production runs, which are not meeting her standards, and she sends samples and we converse at some length before making decisions about which option I'll obtain for the classes. Because of the issues involved, I need to redesign part of the class plan and figure a different way to demonstrate the point I wanted to make. Her yarns will be there. My point will get made. Those two goals just won't happen in conjunction with each other.

Another source never replies to my inquiry, although that's unusual. I do have to find another supplier for that breed's yarn, because I'm determined to include it.

More yarns arrive.

I wind more skeins into balls.

When it's time to visit family for the holidays, I take yarn with me and during in-between moments I begin to prepare the sample kits for class participants. When I'm ready to fly home, I have a duffel that doesn't have anything but yarn in it, and all of that yarn is workshop-ready.

Unzipping it causes a minor explosion (the packs below those on the surface are still compressed).

There's more yarn waiting for me at home.

I count the samples. I count the breeds. I compare the lists of what I have to the lists of what I meant to have.

The participants in Understanding Breed-Specific Yarns (workshop is full) will be treated to:

Black Welsh Mountain

Border Leicester

Cormo

Corriedale

Gotland

Herdwick

Icelandic

Romney

Suffolk

Those in the Introduction to Rare-Breed Wools (which has a space or two! - edited to add: full again; one of my followers on Twitter, where I'm @effortlesszone, snagged what was apparently one spot released by someone with a change of plans—it had sold out on the first day) will discover:

Cotswold

Karakul

Leicester Longwool

Manx Loaghtan

Navajo-Churro

North Ronaldsay

Shropshire

Tunis

Wensleydale

The only problem with this type of work is that for every breed whose samples I prepare, I not only want to keep the yarn for myself but to order more and make a whole project. However, I remind myself what a delight it is to introduce other fiber folk to all the possibilities that breed-specific yarns open up for them. Still, with each option that runs through my fingers I find myself imagining all the things I could make with it. . . .

Those are just a few of the bags of prepared yarn. I have just over 400 samples wound and ready to go, and last night I printed out the corresponding information cards that I'll give to the people in the workshop to help them keep track of what they're experiencing.

That's just for two classes, and short ones at that. Next I need to be sure that the fibers for the Madrona spinning workshop are ready; get moving on washing two fleeces (and making final selections for two more) for Explore 4 (there's another note about this event below); and begin the selection and acquisition processes for Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival, which will follow before long (I've been completing paperwork for Maryland this week: lots of details).

Oh, and now that I know which breeds will be in the Madrona line-ups, I can start putting together the background material: the slides and the handouts.

____

Internet radio interview

Meanwhile, yesterday I was interviewed on an internet radio show about the article that I wrote for the November/December issue of PieceWork magazine, called "On the Edge: How a Handful of People Have Preserved Some Rare, Valuable Sheep and Their Wools." The show, broadcast live, is Creative Mojo with Mark Lipinski. Mark is an energetic, opinionated, outspoken host and I only hoped I could keep up with him! The show is two hours long and I was the second guest, beginning about 45 minutes into the program. It was fun, and the results are available now as a podcast.

____

Early

Veering toward a completely different topic, Tuesday morning shortly after I got up I noticed that the light outside had a very warm quality to it. I looked out the window and noticed we were having an especially beautiful sunrise, so I grabbed my camera and ran out front in my pajamas to see if I could catch it to share.

This was 7:20 a.m.:

And by 8:30 a.m., just over an hour later, the same view had acquired its more normal winter coloration:

I'm glad I didn't miss the show!

Come to think of it, that's sort of how I feel about breed-specific and generic wool yarns. The generic ones are lovely, reliable, and nice to work with. I wouldn't be without them.

But the breed-specific ones are something else.

___

Explore 4

A month after Madrona comes the Explore 4 Retreat in Friday Harbor, Washington (March 10-16). It's a fiber-based event, for spinners at all levels beyond the basic skills of spinning and plying.

Most of the workshops I offer are surveys, in which we cover a lot of ground really fast. They're fun and energizing.

Explore 4 will will be quite different, providing an unusual opportunity to relax and go into more depth with fleeces from four carefully selected breeds. I'll share more of the process of preparing for that event as we go along here. Registrations have been arriving in clusters as people hear about it through various channels (all word-of-mouth, in this case), but there are still some spaces available.

___

And now it's time to make another checklist.

January 2, 2012

Holidays

The year-turning holidays are always a bit disjointed for me. Here are a few tidbits from recent travels.

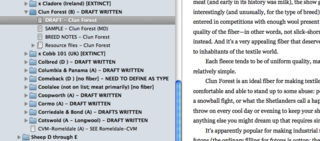

First, an art assemblage I saw being constructed at Denver International Airport a while ago. It is ephemeral, as is its topic, and it will be going away. I'll miss it.

It extends through both sides of one of the arched bridges between the terminals and consists of 10,000 paper cranes constructed from an unpublished manuscript, along with similarly sized crystals. Called "Shadow Happy," it is by Brianna Martray.

DIA's copy of the artist's statement is here. There are many more photos on the artist's site, as well as a link to a YouTube video (about 11 minutes long) about the installation, which I'm so glad to have had the opportunity to see part of. I flew in and out of DIA a number of times during construction, guessing at and then having revealed the reasons behind the blue-tape markings throughout the passageway.

"Shadow Happy" will be in place through February 2012 along the walkway from the main terminal to the A concourse.

______

Because of our travel plans, I wasn't able to be in Salida, Colorado, for the winter solstice celebration of the life of my friend Richard Cabe, who left this plane of existence on November 27. Richard, who was among other things a sculptor who saw rocks as "ambassadors of the earth," worked in a way that was as elemental as, although dramatically different from, the vision in "Shadow Happy." (That last link contains a couple of pictures of Richard shaping granite, and a mention of a scholarship in his name to support other artists.)

In our luggage, my daughter and I carried with us some of the materials to make luminarias in Richard's honor, linking the memory of his life to another part of the globe that was important to him, the one we were traveling to, the Pacific Northwest. My sister and brother-in-law had on hand the other items we needed.

It was, fortunately, not raining. Beanie the cat supervised, as did the heron my sister received as a gift one Christmas.

The luminarias burned a long time (except the two that Beanie knocked off the deck rail).

____

Speaking of Beanie, she helped wrap presents:

. . . and got into my luggage and retrieved (and claimed) a plastic-wrapped fish knitted by my friend Jodie Aves. She liked it even better after we took the ripped plastic bag off.

It seemed to make her very happy.

____

The family gathering lasted close to a week and involved our two 87-year-olds, plus honorary long-time family members (I'm not sure what J. is doing with my aunt's cane, but neither she nor Mom looks worried) . . . .

. . . and, for the first time, one of the younger generation participating by video chat from across the country.

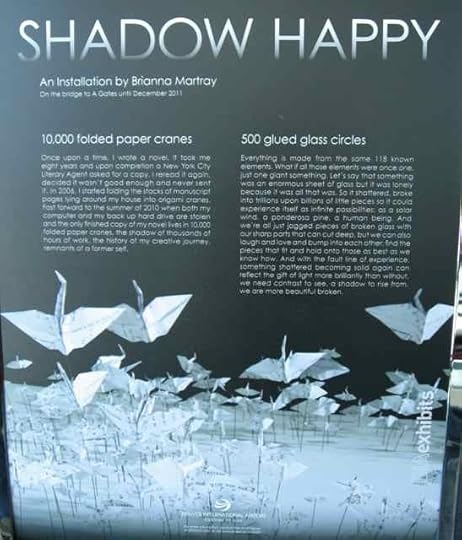

I spent a lot of time doing preliminary sorting of family photos and artifacts from the boxes we packed when we moved Mom to an apartment a couple of years ago.

That's just the start of one section of the 1940s material, which included about 200 photos Dad took in China/Burma/India.

____

We were home in time to pick up the dogs from the kennel on New Year's Eve, although I drove the backroads to get there because of the high winds—the interstate is exposed for most of its length. I learned later that it had been closed altogether for a couple of hours that morning. Our trip was uneventful, although the winds had also knocked out traffic signals along our route, and it was good to have the two-legged and four-legged household reunited.

A quiet evening was topped off by neighborhood fireworks (the official city ones had been cancelled because of the weather), which gave Ceilidh an opportunity to demonstrate exactly how small a corner a dog of her size can fit into.

I think her perception is accurate that there is safety in the vicinity of a spinning wheel, a ukulele (the black case along the bottom), and a supply of dog food (the white container).

____

We also played Settlers of Catan on several evenings, as well as one round of Carcassonne, and my daughter and I got my mother and a friend of hers past their stuck spot on one of their jigsaw puzzles. I also managed to get almost all of the yarn samples prepared for teaching at Madrona, but that's a story for another day.

____

May 2012 bring us all lots of friend-visiting time, good conversations, rewarding work and discoveries, and restorative play.

___

Edited to add another "we're home" photo, actually the one that started me writing the post. I looked down this morning and saw this, which amused me a great deal:

It's obviously an indicator that I'm in a familiar environment.

Happy new year again.

December 20, 2011

Kristi's Nourishing (Nibbles and) Knits

During my years as an editor at Interweave Press, I didn't have time to participate in any fiber groups—other than those that naturally arose as part of work, which were more task-oriented than social. I still don't have a lot of time. So I'm especially happy to have found, a number of years ago, a particular knitting group. We meet one night a week. We have no scheduled activities. We show up, we knit, we talk, we occasionally vent, we often laugh, we go home. Oh, yes, we also eat. Because we start showing up at 6 and hang out until at least 8, maybe 9 or later, we do have food around, although it's not planned.

This is the group that supported me through the research, spinning, and writing of The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, although most often—unless deadlines were just too imminent—I'd take my R&R knitting, like the Ink sweater. When I showed up with my spinning wheel, these good folks would know that I was seriously scrambling. I'm grateful for the ongoing and unqualified friendship of each individual and of the cluster that includes us all.

(Four folks are missing from that picture: Kristi Schueler, who took the photos of the group at our gathering last week; Dee, whose dining room we refer to as "the clubhouse"; Irene, who participates more often in the summer; and Ashley, who now occasionally commutes from her new job in California. Present are Kathryn, Amanda—who can be recognized as one of the models in Nourishing Knits—Sarah, me, and Rebekah. Rebekah's wearing her first completed knitting project, a blue wool pullover with a cable motif on the front.)

This group has also informally supported another recent project during its development: Kristi's Nourishing Knits: 24 Projects to Gift and Entertain. This electronic book contains a dozen knitting projects and a dozen (well, a generous dozen) recipes. The yarn-related and kitchen-based components are paired, with stories about each. Kristi is a gifted knit designer, recipe deviser, and photographer (she took the author photo of me that's on the back of Fleece and Fiber). We watched the development of the patterns and we taste-tested the recipes, sometimes in multiple iterations (from yum to WOW).

In the next photo there's Dee, pouring the spice tea that makes our world go 'round. (Recognize the sweater I'm wearing? Sarah's working on a Swirl, and has actually figured out how many stitches are in each section, as well as a total, and gives us reports on her status. She's an engineer. Dee's working on a Swirl of her own, and being an accountant has prepared a spreadsheet and revised some calculations: her work-in-progress is on the table in front of her. I think Kathryn is knitting socks. Rebekah is making another sweater. I have no idea what I'm knitting. I may have ripped it out. No, I think it might be a Christmas present that will be ready by spring.)

In addition to providing perspective, useful and not, on Kristi's knitting designs, we have joyfully contributed reliable feedback on her kitchen adventures. In the reddish glass by Kathryn and on the plate in front of Sarah are a few remaining saffron pastries that Kristi brought last week. They were absolutely scrumptious: not too sweet, delicately flavored, satisfying.

Nourishing Knits contains lots of options of the knitterly and cooking varieties. I subscribed to the early version of the book, so I've been getting updates as things progressed. Now it's finished, and I have the whole thing! You can, too. It's currently available only through Ravelry, the online knitting community (free memberships), but Kristi is working on a landing page on her website as well so non-Ravelry folks can get it.

One of the patterns in the book is "Guided by Love," a sock design constructed on one of Cat Bordhi's architectures so that pawprints go spiraling from the toe area up to the cuff, with "guided by love" added in braille beadwork around the top of the sock. (Note: Designing pawprints in lace is no small accomplishment. I've done it, independently. Getting the components to line up correctly takes a lot of trial and error. Kristi's standards for how things will work are really high.) Early sales of this pattern earned $1400 in donations for The Seeing EyeTM. The accompanying recipe is for Bow Wow Biscotti, dog treats that were tested by Kristi's dogs. . . .

very sweet Emma, who will, if she knows you pretty well and you don't look at her directly, let you pat her:

and spicy Brandon, a more recent addition to the household:

as well as our dogs, Ceilidh (with some of the yarn for Dee's Swirl). . . .

and Tussah, who, like the others, doesn't get fed people food but is hoping for a pup-biscotti:

. . . plus Amanda's and Sarah's dogs, and maybe some others as well. Everybody's been involved in Kristi's book, at least at the tasting level. All of the dogs shown here are rescues. Being rescued to test Kristi's dog treats is a pretty good deal for a dog.

Looking over the finished product of Kristi's book brings back lovely memories for me. The patterns and food ideas in it have been carefully selected to create similar fine memories for you.

Because it can be hard to know where to start, I'll pick out four of my favorite patterns and recipes.

Although I like and would knit all the patterns, the specific designs that I personally would be happy to cast on for immediately, and be working on by tonight, include:

"Buttercream," elbow-height hand and arm warmers with twisted-stitch patterning and shaped thumbs

"Challah," warm warm comfort socks

"Masala," unique slippers, and

"Ciabatta," a sweater to steal from the guys

I'd revisit all the recipes. Yet the ones I want to make this week are:

Savory Pesto Cheesecake, even though I don't like cheesecake! (it pleases cheesecake lovers and non-lovers alike)

Smoky Sweet Pumpkin Seeds, which I should warn everyone are addictive

Chai Concentrate, created in the spirit of a local restaurant's exquisite brew