Deborah Robson's Blog, page 12

June 11, 2012

High Park Fire, 1

I had a great weekend at the Estes Park Wool Market, which I'll write about soon, but at the moment obsessed with the High Park Fire, currently burning in Larimer County, Colorado, where I live. We thought the recent Hewlett Fire, started in mid-May, was bad. It was, and while contained it is still burning. (The first date I pick up for newspaper notifications is May 14.) On June 4, the Stuart Hole Fire got going. And on June 6, the Camman Fire. Now we have the High Park Fire.

Let me tell you a little about it and why it's got my attention.

Saturday

When I went to pick up a friend to go to the wool market on Saturday morning, I saw a plume of smoke on the horizon and thought, "Uh oh."

Saturday, 10:20 a.m., from Fort Collins

By my quick eyeballed estimate, Estes Park is about 25 miles, as the crow flies, southwest of Horsetooth Reservoir, a landmark that I can use to mark the lower part of the fire-evacuation area. From Estes Park, this is what that plume looked like about 2.5 hours later.

Saturday, 1 p.m., from Estes Park

When they say it's a fast-growing fire, that's what they mean.

Saturday evening, as we walked the dogs, this is what the fire looked like from our neighborhood.

Saturday, 5:50 p.m., from Fort Collins (from our back deck)

Saturday evening, as we walked the dogs, this is what the fire looked like from our neighborhood.

Saturday, 8 p.m., from Fort Collins

That's the view across the park about a block from our house, looking northwest.

Sunday

On Sunday, I was at the wool market again, working (had a great time, except for the worrisome views to the north). We left the house at 7:45 a.m. Throughout the morning, from both Fort Collins and Estes Park, the smoke was a haze across the horizon (and at home, there was ash on the newspaper and all over the cars in the driveway).

By afternoon, the wind patterns, and possibly fire behavior, changed so the smoke was again dramatically visible.

Sunday, 3:20 p.m., from Estes Park

I got home about 5:30, had a bite to eat, and then we took the dogs for a walk. The color in the next two photos, taken from our neighborhood, is from the sunset. It's gorgeous, and extremely eerie. The photos are looking to the northwest, although we could also see evidence of fire directly to the west.

Sunday, 7:15 p.m., from Fort Collins

Sunday, 7:18 p.m., from Fort Collins

I didn't intend to get my daughter in that photo, but there she is. The dogs, of course, are out of the frame.

Overview

I have, of course, been reading information online. The best official sources I have found are the Larimer County emergency notifications and the Inciweb reports (note that to see the full extent of the fire perimeter on the maps, you will now have to reposition the view). The best news source I have located is KUNC, which is not broadcasting over its 91.5FM frequency because the transmission tower has been knocked out by the fire but is providing web feeds and excellent online summaries (succinct overviews, understandable, current, and accurate—as gauged by the county and Inciweb reports). KUNC also offers selected links to other coverage.

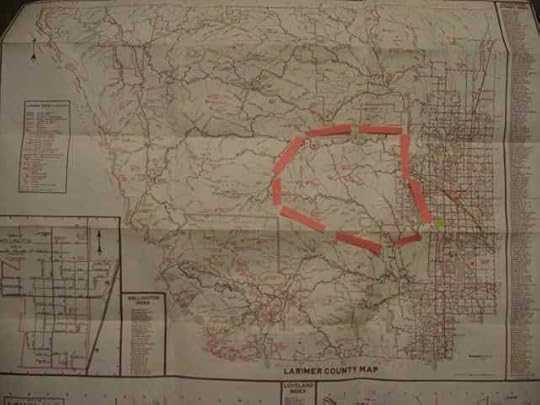

Reading all the road closures felt like a patchwork, so I took out an old county map to get a sense of the evacuation area. I'm really visual. This shows the whole county, which is large: 2634 square miles (6822 km2). The evacuation area is within the pink flags. Some sections have been evacuated because the fire threatens to cut off all escape routes. The gridded area on the right is the city of Fort Collins. Road closures begin 1.5 miles west of our house.

We're okay, although we have to keep our windows firmly closed. It's stuffy in the house, but that's not something to complain about.

The latest report on the fire area itself includes 36,930 acres, or just under 58 square miles—probably more than that by now, because the fire is growing, with 0% containment. The best information on extent appears to come after evening infrared assessments from the air. (The city of Denver covers 155 square miles; Boulder covers 25 square miles; thanks to KUNC for those numbers. Fort Collins covers somewhere between 47 and 53 square miles, depending on what you count. The city's website doesn't seem to have information on its area.)

Because fires are erratic and unpredictable in their behavior, I am hoping for the survival of the 17 wolves that could not be evacuated from the W.O.L.F. Sanctuary. They have newly constructed, but of course untested, fire dens. Thirteen wolves have been removed from the sanctuary. (The best information on the situation at W.O.L.F. I have found is on the WOLF Sanctuary Facebook page.) Several of these wolves provided fiber for The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook. The intelligence and dedication of the people who run this sanctuary are exemplary, as is the difficulty of the work they do.

I am also hoping for the survival of other animals that have not been able to be removed from the area, and for all humans who have gotten caught in this mess. Humans are easier to move out than livestock or wild animals.

Beyond all that, some of my favorite landscapes in this entire region are going up in flames.

Drought + beetle-kill trees as fuel + heat (90°+F on Saturday) + wind + a spark = inferno.

The suspected immediate cause is lightning, although there are deeper causes that have produced the drought and beetle-kill and changing weather patterns.

The note I am holding in mind from the just-issued county report (11:17 a.m.) is this one: "There are many unburned areas within the perimeter of the fire, so residents should not assume their homes are damaged or destroyed."

May 25, 2012

Aphasia, and apraxia of speech

Three weekends ago, I was at the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival. Two weekends ago, I was at Shepherd's Harvest in Minnesota. I flew back from Shepherd's Harvest not certain whether I would go immediately from the arrival gate to a departure for Seattle; my mother had a stroke just before I left on the Minnesota trip, and we were monitoring the situation closely on a daily basis throughout the family. (Note: There are no direct Minneapolis-to-Seattle flights on United. When checking options, I learned that to get to Seattle as soon as the festival was over I would have had to return to Denver on my regularly scheduled flight and then catch a plane for Washington.)

As it turned out, I went home for four days to do laundry and bills, and to re-pack my suitcase. (During that time, the Hewlett Fire erupted in the mountains nearby, and we all were tracking that as well, taking action and preparing refuge for human friends and animals in the fire's vicinity. It's been way too exciting around here.)

On my mother's 88th birthday, I flew to Seattle to lend a hand as well as I could, and to learn about things like aphasia, as well as apraxia of speech, which Mom's stroke has caused. The ability to communicate, through speech, writing, and other means, plays a normally invisible and absolutely crucial role in every other aspect of living. We didn't mention her birthday to her. Despite my arrival, which got a smile out of her, that day wasn't so great. We gave her the cards a couple of days later, when things were, at least for the moment, looking a bit better.

Aphasia is neurological damage affecting language functions, including speech. Apraxia of speech is a type of speech disorder in which the brain knows what it wants to say yet the muscles can't translate those ideas into forms that other people can understand. It's not muscle weakness. It's like the muscles have lost known skills. The brain knows the ability should be there, and the means of articulation don't cooperate.

It's incredibly frustrating for everyone. Watching Mom attempt to speak is like watching someone in a swimming pool try to capture brightly colored balloons that skid away across the water's surface just as they come within reach.

She can hear and understand what we say, and can nod "yes" or "no" in response to questions. My sister is much better than I am at thinking of questions to ask that will yield useful information. Then again, my sister's full-time work in the public school system involves teaching autistic (and other) kids about movement and dance.

I have an unusual amount of experience with communication issues posed by neurological and psychological challenges. I've dealt with situational muteness. I'm good at thinking of alternative modes of communication. Most of the ideas I could come up with this time didn't work.

Mom can't write. We're not sure about reading, although she enjoyed having me read to her (Erma Bombeck's newspaper columns worked well: good lengths, good topics, and mostly humorous; when she's feeling okay, Mom's sense of humor and of the absurd appears to be intact). My sister read to her the previous week, and my niece, who had flown in to help and left the day I arrived, brought Mom some music.

We're working on how to get more music to Mom. She doesn't seem any more interested in television than I am, yet operating electronic devices that might play music is a bit beyond what she can do. The speech-and-language therapist says Mom is 100 percent accurate in responding to one-stage requests. ("Touch your nose.") Her accuracy drops somewhat when the requests move to two-stage sequences ("Touch your nose and then touch your ear."). I don't recall the percentages exactly, but I think at that level she varies between 70 and 90 percent accuracy. That's not bad for a short time post-stroke, but so far we can't think of a music-playing device that would be familiar to her, and operating a new-to-her option would require her to learn a sequence of actions. Since her energy is limited, we think she would be better off spending it in reinvigorating her how-to-talk skills. But it would be great if she had some music, and could control it. Rehab can be a really boring existence when your non-therapy alternatives are so limited.

In trying to decipher Mom's utterances when she was working on communicating verbally, I was hampered by the amount of noise in most of the spaces where we were located—it's a rehab facility, and in the daytime there's a whole lot going on. Mom's articulation isn't clear and she can't vocalize very loudly. On one day, it was sunny and we went outside into a courtyard and that was delightful. The next day it began raining, a situation that continued for the rest of my visit; the precipitation was good, but the limited access to quiet space was not.

On the occasions where all of us (especially Mom) managed to muster enough patience to slow down and make our way through a whole sentence, Mom was able to convey quite complex ideas. The high point in my week came when I guessed the word "niche" and got a strong affirmative nod from her. "Niche" is a really hard word to speak or interpret!

Right now, it's hard to tell what sorts of recovery the rehab therapies may accomplish. The aphasia and the apraxia of speech are not the only things Mom's dealing with, but they are the core issues. Mom's doing physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-and-language therapy. At the evaluation and treatment planning session we all participated in on Monday, the overall opinion was that she may be able to regain nearly all of the independent skills she has currently lost. (I learned that ADLs are activities of daily living, the benchmarks for independence.) But her success will depend on a few things that we can influence, as well as many things over which we have no control at all. It's one day at a time.

And we will do everything we can to support her.

This is why.

It's impossible to tell what will be needed in the family constellation over the next few weeks or months. My sister and brother-in-law are handling the great bulk of details and visits and paperwork, due to their proximity. The rest of us are doing everything we can, either from a distance or by showing up in person.

One day at a time. One step at a time. One word at a time.

May 24, 2012

Shepherd's Harvest Festival 2012, in Minnesota

Weekend before last, both authors of The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook—Carol Ekarius and I—flew to Minnesota for the Shepherd's Harvest Festival, which was celebrating its 15th year. It's a lovely event, held at the Washington County Fairgrounds in Lake Elmo, east of the Twin Cities but easy to reach from the metropolitan area. This gathering has many of the attributes of the Maryland Sheep & Wool Festival although on a smaller and more intimate scale.

They've got music. This is Paul Imholte, who's an amazing multi-instrumentalist.

I first encountered Paul and his music when Shelley Hermanson and I were judging the skein contest. Before he began to play, Paul came over to ask if it would be okay for him to set up nearby. I really appreciated being asked, because judging requires both concentration and, in this case, conversation between the judges, but we took a quick look at him and his instruments, took a mental leap, and said "No problem!" So we got to listen while we worked. It was a good choice.

That beautifully built cart in the background stores and transports Paul's instruments and CDs. It's a very efficient and versatile set-up. We got to enjoy his music at several other locations. Sometimes there were 20 or 30 people standing around tapping their feet or dancing in place. In the case of the photo above (which I took while we were doing one of our two book signings), a young fellow was learning what to do when the music won't let you stand still.

According to the program, there were other musicians. But because of where and how I was working, I didn't happen to hear any of the others.

There was shopping—several barns full. I'm highlighting Bleating Heart Haven for two reasons: one was that they were selling their own fiber in a very constructive way. . . .

The other is that their yarns were clearly labeled as to fiber components (specific fiber types, at the breed or grade level). As large and shiny as the labels were, they didn't interfere with shoppers' ability to look at and evaluate the skeins, which were lovely.

Bleating Heart Haven does a great job of farm-to-finished processing, design, and marketing of its fiber. It was so easy to browse and know what I was looking at! Bleating Heart Haven has a variety of types of animals producing their fibers. Even booths with single-source fibers could benefit from clear labeling of their breed-specific and home-grown yarns. Usually I have to hunt for the presence and identity of the yarns I'm most interested in.

The animals were over in another set of barns. The shepherds and farmers were on site to educate the public, sell wool or stock, and otherwise be ambassadors for their breeds. Here's a young Horned Dorset lamb with a shepherd who had interested onlookers—with good reason—every time I passed by.

The barns were stroller- and wheelchair-accessible, as were the animals.

The weather for the weekend was perfect, and there were plenty of visitors to the festival, but it never felt crowded.

Some of the sheep went on walkabouts to look at the people. Sometimes they got to go outside and enjoy the grass.

(Yes, there was a booth with lefse. I didn't have time to try it and compare it to our family's versions. It's true, I'm pretty spoiled by our family's versions, and when I read other recipes, I tend to think, "They're making it too complicated, too rich, too . . . not perfect." Norwegians can be very opinionated about their lefse.)

Other sheep helped demonstrate what rooing is (collecting wool as it naturally sheds: shears are used only on bits that haven't quite loosened up enough, and the rest is just hand-gathered). The folks below represented the Fine Fleece Shetland Sheep Association. That young sheep was experiencing her first rooing. She was very calm about it all. I think she was ready for her summer wardrobe.

What's funny in that picture is the way the sheep fits (or doesn't fit) a standard grooming (or fitting) stand, any more than her "shearing" process fits the usual trimming technique used for sheep being shown in competition. That vertical structure at the left in the photo is usually used to support the sheep's head while it's being groomed, so it won't jump off the stand or get its ears nicked by the shears. This little one just needed a halter tied to the post to make sure she stayed safe. But all of the sheep I saw at this show were calm because the whole event was so low-key.

Carol wanted to take home Babydoll Southdowns.

Note the size (the bandanna will give you scale).

For comparison, here's a regular Southdown  whose picture I took at the Maryland Sheep & Wool Festival the previous weekend, over waist-high on the person leading it. This bigger Southdown was trimmed for show on one of the stands like the Shetland above is standing on, but its head likely fit in the brace.

whose picture I took at the Maryland Sheep & Wool Festival the previous weekend, over waist-high on the person leading it. This bigger Southdown was trimmed for show on one of the stands like the Shetland above is standing on, but its head likely fit in the brace.

Another barn was packed with llamas (both regular and the long-fleece suris). . . .

. . . and alpacas (both huacaya and suri).

One large stall contained baskets of more than a dozen types of fiber for people to look at closely and even touch. The photo shows just one section.

It wasn't fancy, but it was very smart to do and interesting. People enjoyed the ability to compare side-by-side a number of different types of fibers.

And then there was me and Carol.

We presented three programs, all as slide-talks. We both have ties to Minnesota and were glad to be part of the event. Our Saturday evening talk (where this photo was taken: thanks, Sarah Jane!) was about how we wrote the book. Then on Sunday we gave one talk for people who want to use different types of fibers and another for people who want to grow and sell fibers to folks like us.

Here's the weird thing. While Carol and I both live in Colorado (and have also lived in Minnesota), our homes are about four hours apart. We haven't seen each other in person since the Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival last year. We met up at the airport to fly to Shepherd's Harvest, boarded the plane, found our seats, and Carol mentioned she'd brought her knitting. I asked to see it, and she pulled it out.

"Wait a minute," I said. "BFL?" (Bluefaced Leicester)

It was. She's making her mother a shawl from worsted-weight yarn.

"Where from?"

She pulled out the tag: Lisa Souza Knitwear and Dyeworks.

"WAIT just a minute." I pulled out my knitting. "BFL. Lisa Souza. SOCK weight."

We're both working wool from the same sheep breed. Obtained from the same source, and the same small-scale dyer. We're even working with the same hand-dyed color: Forbidden City.

This was NOT planned.

What are the chances?

And that's how the visit to Shepherd's Harvest went: serendipitously well.

May 20, 2012

Seattle downtown on a Sunday, not where I planned to be

This is a total digression. I have more wool posts, but on a Skype call with my daughter last night I mentioned the drive I took yesterday from SeaTac through Seattle, and she wants to see photos.

I flew in (my mother's ill), arriving an hour late because our plane was delayed to permit people coming from the east through a thunderstorm to make their connections. Picked up the rental car and called my brother-in-law to let the family know I was on my way to their house. He mentioned that the highway 99 viaduct is closed this weekend for construction, and the only option for the southern part of my trip would be I-5, and that it would be crowded. He mentioned that getting off the freeway when possible and taking 4th Avenue through downtown would be a potentially good alternative.

I know Seattle somewhat, because I lived here 40 years ago and took the buses back and forth between Lake City (way north), downtown, and my classes at the University of Washington. Things have changed a little between then and now, and I have never done much driving in this city. I did have a map (not very detailed) from the car-rental agency. (I forgot to bring a better map, and I'm not sure it would have helped.)

The freeway became a large-scale parking lot beginning about 2 miles south of downtown, so I edged over and exited at something called Martinez. It appeared to be willing to connect to 4th Avenue, but that didn't work out: I could SEE two lanes of access to 4th Avenue, but the elevated highway segment I was on wouldn't let me get to them. I headed north and attempted to find 4th Avenue by driving around some stadiums (post-1970s construction) and ended up on 1st Avenue South, where some event was going on involving teams of people running through the streets wearing costumes or at least matching t-shirts. I think beer may have been involved. There were a LOT of teams: hundreds of people. One team had Viking-style horned helmets and armor that I think was made of Rainier beer cans.

I ended up progressing slowly through Pioneer Square (my first, four-week weaving class, in 1971, was in a second-floor space in Pioneer Square; I transported my rented Pioneer table loom there on the number 7 bus from Lake City). I decided to delay my attempts at finding 4th Avenue for a few blocks because I wasn't sure I could access it from the clutter of streets around Pioneer Square.

I figured out that the people I was seeing darting in and out of traffic were likely participating in a large-scale scavenger hunt. Reason? MANY people running in front of my car when traffic slowed to a stop (every 5 feet or so) to get their pictures taken with the license plate of the car in front of me.

The car from California had cut me off when I was attempting to merge onto some more-major street from the narrow alley near one of the stadiums (stadia?) that I'd inadvertently gotten onto while looking for a way to get to 4th. At this point, I became glad that the California driver hadn't let me in, and that the more generous driver following it had, because being behind that car made my travel across lower downtown Seattle a lot more interesting than it would have been otherwise.

Note the "construction ahead" sign. This was also a theme of the day. And more frequent than the photos indicate. I only snapped pictures when I was not moving.

The construction was not minor.

Nor was the event.

When people were not running in front of my car, this is what they were doing:

I headed up the hill, still seeking 4th Avenue (lots of one-way streets to figure out, with more construction, undocumented because my car was actually moving).

I did find 4th Avenue. My connection to wherever I went next involved going down a street that my map, also studied when I was fully stopped, suggested was the connector (Battery). Once I turned onto it, the two lanes (out of three) that went where I needed to go were clearly marked BUS ONLY, but (1) I couldn't see how else to get there and (2) lots of other cars were using the BUS ONLY lanes. So I followed them.

Whew. I decided to park the car and walk as much as possible for the rest of the day. But my journey was a whole lot more interesting than I-5 was!

While walking back from visiting my mother, here's a bridge I waited to cross:

I am undoubtedly not the first person to think this looks like a TARDIS:

(There are actually four of them on the Fremont bridge.)

May 17, 2012

Maryland Sheep & Wool Festival 2012

I'm so far behind on blogging that I'll never catch up, so here's an overview of this year's wonderful Maryland Sheep and Wool Festival. I taught a two-day workshop on rare wools, participated in as much of the book signing as I could get to, and facilitated two walkabout classes in the barns, which was a new event and a lot of crazy fun.

Here's everybody except the photographer (and me; I'm organizing things off to the left) concentrating on a new fiber. (Thanks, Nancy, for taking pictures while I was all-out focused on teaching!)

One of the biggest reasons that I love teaching is the great people I get to meet. And that's a roomful of them.

And here are the fibers at the start of the workshop:

We worked our way through them over two days. Our selection for this workshop included:

Black Welsh Mountain

Clun Forest

Dorset Horn

Gulf Coast Native

Jacob (American)

Leicester Longwool

Navajo-Churro

North Ronaldsay

Oxford

Romeldale/CVM

Santa Cruz

Shetland

Wensleydale

. . . and, courtesy of BitsyKnits, a sampling of Sharlea, which is a rare wool although not from a rare breed (it's specially grown and prepared Saxon Merino).

Thanks once again to The Spinning Loft and Spirit Trail Fiberworks for making these workshops possible. There's no way I could acquire, wash, and prepare all the fibers myself. I do some of that work: The Spinning Loft does most of it, with essential contributions from Spirit Trail.

On several of the evenings, after we had finished teaching, Maggie Casey and I were lucky enough to walk around the lake near the hotel. (I was looking for a photo of Maggie, but we'll have to settle for a selection of her DVDs and her book.)

The barn walkabouts on Saturday and Sunday mornings were amazing. Registration was limited to a small group so we could move with relative compactness through the barns and talk about wools in connection with the sheep that grow them. We only had time to do barn 8: and it was a full three hours! There was a lot of variety in breeds and many topics to consider. The walkabout description said we'd cover between 10 and 12 breeds. Because they were there, we saw and talked about more than 25!

On Sunday, I juggled myself back and forth between the walkabout, the book signing, and the Parade of Breeds, which is my favorite event at the festival. Here's a Border Cheviot (in front) and a Border Leicester (behind):

My favorite Shetland ram was there again, once again charming everyone within viewing distance. This year he had been shorn before the festival—many more of the sheep were in their summer wear this year than usual. The dogwoods and azaleas had also passed their bloom-time (climate change affecting shearing, as well as blossoms?).

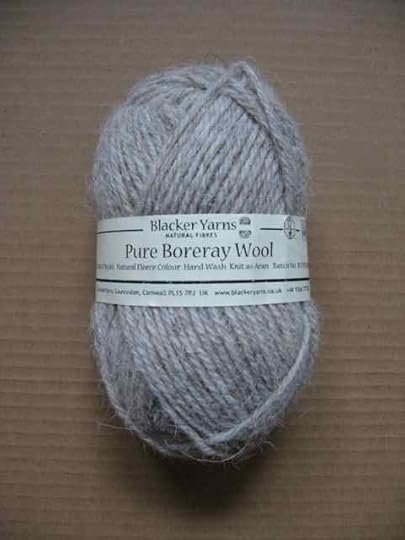

Sue Blacker and Douglas Bence of Blacker Designs and Blacker Yarn in the UK attended the festival and gave a presentation on the value-added work they do to increase shepherds' and farmers' income from the fiber their animals grow. One of the things they have done recently is work with some wonderful, visionary people to produce what is likely the first commercially spun Boreray yarn, and here's a ball of it!

Boreray is a rare breed of sheep from the same small set of islands, called St Kilda, that are home to the Soay. This Boreray yarn is one of two that the Blacker mill is producing. The other will be a blend of finer Boreray fleeces, hand selected, with Soay wool, as a St Kilda laceweight. I can't tell you how exciting this is. It's one of the fantastic ideas that grew out of the odd experience that was UK Knit Camp in 2010.

What with teaching, book signing, and a few wonderful meetings, I finally got to walk around the festival for a short while at the end of Sunday. I spent most of that time taking pictures of sheep. And this Karakul sheep from Redgate Farm looked exactly like I felt at that point:

So it was time to call the festival a huge success and wonderful time, and to go home.

At least for a few days.

April 19, 2012

Moose!

It's been silent around here because I said "yes" to too many things, some of which don't help pay the bills (but were irresistible) and thus make paying the bills even more challenging than usual. I've been teaching; planning for future teaching events; freelance editing; trying to keep on top of Nomad Press concerns; and writing articles on topics that are huge, complicated—and fascinating.

There will be an article in the summer 2012 issue of Spin-Off on the relationships between fiber diameter, softness, and crimp (not a full discussion, because that wasn't possible).

Most recently I've been working on another article for another publication, on a HUGE topic that I only took on because I wanted to know enough to write it. Which means I've been researching. And thinking about how to condense the information into the available, limited space. I've been poking at the subject(s) for several months, collecting bits and pieces, writing sections, getting flashes of insight. But I have been frustrated by my inability to bring the scraps together into a coherent whole. In the past, I have been blessed with a week here and there at one or another location away from home, where I could concentrate. I've had an open invitation to use one of these places since January, but I haven't been able to get here.

I saw a two-day spot in my calendar and seized it. I drove up yesterday. I'm in the mountains. It's quiet. While there are uncounted numbers of items on my "to be done by last week" list, my goal for these two days is to complete writing that piece.

As of this morning, I have 1600 of the 3000 words written, and I think they're in decent shape (i.e., won't need to be ripped completely apart and rewritten). There's plenty of material to fill out the remaining 1400 words, although I need to do a little more research before I can write the next section. Plus I slept on an air mattress for the first half of last night, and only the second half of the night (couch) was really restful.

So I decided that after lunch a walk would be a good idea: between snow flurries (the snow from early this morning didn't last past noon).

I intended to walk up to the highest point on the road, then turn around and walk back down. That's always a wise approach to exercise on the first day at an altitude higher than the one I'm accustomed to. Just before the turn to the last switchback, I heard something crunch and looked up.

My camera has a little zoom lens on it, but definitely not a telephoto. (To quote the manufacturer's specs, "a full 6.0 megapixels of imaging power and a high-quality 4x optical zoom lens.")

The reason I heard the CRUNCH was that the other obvious megafaunal inhabitant of that piece of the planet had just taken a bite. And I was that close.

I decided to retrace my steps instead of taking the switchback, which goes up the hill just behind the amazingly multi-hued diner.

Here's what I saw as I descended:

That gives a sense of how steep the terrain is and how the moose and I hadn't noticed each other until I was pretty much eye-to-eye with it.

Heading downhill again, there was this:

And then this:

Which turned out to be this:

That photo isn't as clear as the first one because I was walking on the far edge of the dirt road, to give as much space between us as possible, and I just held up my camera as I was passing and clicked the shutter. The first moose seemed calm despite my presence. This second one was a bit skittish, and less sanguine about my presence. I didn't want to disturb either of them. The path of least disturbance was the one I took.

To get enough walk in, I went to the bottom of the road, coming across this:

Apparently at least one of the moose had been down lower earlier in the day. Not much earlier: the scat was pretty fresh.

So I huffed my way back up the hill, feeling like I'd chosen the perfect time for a break. Here's what the weather looked like as I climbed:

And now I need to sit here at the table and sketch out a timeline of a couple thousand years so I can write the next paragraph or two of that article.

There's a lot of sheep-related stuff going on in my life, including several blog posts I've started but not had time to finish. Those stories will have to wait, unfortunately, for clearer brain-space.

Happy moose day, though!

February 25, 2012

Shipping wool internationally

Carol Ekarius, co-author with me of The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook, was our primary coordinator of obtaining samples that I then analyzed, washed, recorded, and spun. Therefore she's the one who needed to figure out the logistics and legalities of moving wool, in the quantities we needed, across various types of boundaries.

She wrote up her findings. I've added some links and the 2012 update of countries' Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) status; the need to prevent the spread of FMD is the reason for caution in transferring animal products between countries.

In short: It's easy to ship wool. You can make it VERY easy by knowing what the regulations are and putting a couple of extra sheets of paper inside your package. For the most part, the papers aren't necessary and the wool goes through without a hitch (as it should). But we're all about preventing problems, whenever possible. (Moving meat products across borders is a whole different issue.)

________________________

Getting Your Raw Wool Fix from Far Away:

Or, importing raw fleeces to where you call home from foreign ports of call. . . .

by Carol Ekarius, co-author of The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook

I have seen a few questions popping up in places where people are talking about The Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook that go something like, "Now I am finding out about all these breeds, I'd like to be able to [buy/sell] fleeces to or from [fill in the name of a locale]. Can I order them from overseas and have them shipped in, or are there issues with importing raw wool?"

I actually looked into this somewhat as we were working on the book thanks to a conversation I had with Tim Booth, our wonderful friend at the British Wool Marketing Board (BWMB). Tim went above and beyond the call of duty to (with the help of some other BWMB staff) get us many fleece samples and photos for some tougher-to-find British breeds. He said that BWMB was a bit cautious about sending fleeces to the United States because they sometimes got held up at customs, and occasionally rejected. Rejects got shipped back, which cost a bunch of money on what is still a low-value commodity overall.

Was I familiar with the regulations? he asked me.

"Not offhand, but I'll find out," I responded.

Importing to the United States

I called the Animal Plant Health Inspection Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (it's called APHIS for short). I was quickly connected with a veterinarian who said it is fine to import wool from many countries, as long as it isn't covered in blood or manure. He explained that there are countries where Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) is active, and those countries have a few more considerations that have to be taken into account, but those that are FMD-free—including the United Kingdom—should not be a problem.

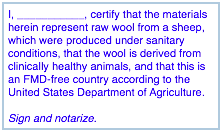

I told him Tim's story of shipments that were turned around by U.S. Customs, and he said sometimes the customs agents, who actually do the inspections, may not understand the rules regarding wool. He told me to check out the Animal Product Manual chapter on Hides and Related Byproducts and he suggested that I send Tim the link with a note to check tables 3.7.14 through 3.7.17 (these charts are available at our Fleece & Fiber website), and he also suggested that the best way to ensure that customs agents know what to do is to include a written statement (see the sample) that this was raw wool from a healthy animal from an FMD-free country (notarized if you are concerned about validating fully), and include the table that shows the customs agent that he or she should release the fleece from customs with no problem so long as it is free from blood.

Lo and behold, these tables are a great resource. They help quickly clarify the process for fibers coming into the United States from FMD-free or FMD-troubled countries. Blood and excess manure are to be diligently avoided, but if you are buying fleece for handspinning, you sure as heck want it to be well skirted, and there should never be any appreciable blood stains on a fleece from a well-sheared critter.

So, if someone in an FMD-free country (list at the bottom of this post) wants to sell wool to someone in the United States, copy the first chart (3.7.14) and include it in the package, along with your statement that this is raw wool from [type of animal] (usually sheep, but could be goat, musk ox, yak, alpaca, or other ungulate not protected as a threatened and endangered species), grown in an FMD-free country. If you are in an FMD-troubled country, include the appropriate chart, and no matter which chart you are using, use a yellow highlighter to emphasize the correct decision mode.

Here's a link to the APHIS publication listing foreign countries and their disease status (including FMD) as of January 2012. It's the resource from which we developed the list included in this post. If you are reading that original APHIS document, note that some requirements (marked FMD/SR) apply to meat-based products only.

Exporting from the United States

This gets a bit more complicated for me, because each country has its own rules, but for European Union (EU) countries, I can define the current status. On February 25, 2011, the EU Commission adopted Regulation No. 142/2011, which allows that "fully treated" hair or wool can be imported into the EU countries from the U.S. and no documentation or APHIS approval is required. The U.S.-based exporter should have the European importer confirm in advance with the Border Inspection Post (BIP), through which the product will enter the EU, that the hair/wool is considered fully treated. In general hair/wool is considered by the EU to be fully treated if the wool/hair has undergone factory washing or been obtained as a by-product of the tanning of hides/skins. Hair or wool that is not "fully treated" doesn't require shipment certification either, but it must be shipped from a U.S. facility that has been inspected and approved by APHIS Veterinary Services to ship untreated hair/wool to the EU. You can find a list of these facilities at https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/sanco/tr...#

The other suggestion from the U.S. veterinarian is to contact the relevant country's agricultural service (in Britain, this is DEFRA, the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, and ask if they need an import permit. He also suggested that you can check with United States embassy in your country and ask for the trade or import/export department, which may be able to help.

February 7, 2012

KDTV: Washing wool

I still need to write the third post about the numbers in The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, but I'm prepping to teach at Madrona and it's all-consuming.

Yet here's a loooooong post that was published on the Knitting Daily TV site today. I'm taking the unusual step of presenting it here as well, because it involved a lot of work and because I want to alert my blog readers that if they go to the KDTV site and leave a comment by noon Central Time on Monday, February 13, they might win some Unicorn Fibre Wash, Unicorn Fibre Rinse, and Unicorn Power Scour.

I've just watched the KDTV video segment on cleaning wool, and considering that host Eunny Jang and I work entirely unscripted and that I wasn't able to get the specific background information I wanted from some sources in time for the taping, I think we did a pretty darn good job. (You may notice my slight discomfort in the situation because of the number of vocal pauses―um―in this segment. I need to learn to relax and trust that I do know enough about fibers to fill a five-minute spot on the spur of the moment, even when I didn't get the info I wanted!)

Anyway, this post contains useful information about cleaning wool. My study of the topic has come up with even more cool stuff that I'll need to write up another time.

I really like the Unicorn products. I'm not paid to say that—not paid here, not paid when I appear in the KDTV episodes that they sponsor, and not paid for the ad they've been running—although Unicorn has helped out with my research by sending me Power Scour to use once they figured out that I think it's great and am happy to say so.

_____________

Washing wool

I love washing wool, whether it's fleece I'm going to spin, a newly finished garment whose beauty will be revealed after its first bath-and-blocking, or a loyal garment that has earned refreshment.

Freshly shorn wool may be the most fun to wash, because of its dramatic transformation. The grease that coats the fibers when the sheep is using the fleece to keep herself warm through the winter is still soft, resilient, and relatively easy to remove. I think of the animal, freshly released from this seasonally necessary burden to enjoy the spring air (and to begin growing next winter's blanket), and I think of the fabrics I will make from her hand-me-downs to keep other beings cosy in the future.

Even long-stored fleece can be rewarding to put through the washing process, which releases it from a stiff accompaniment of old grease and dust. Although it's best to wash wool soon after shearing, in part because moths especially savor the "extras" that are removed when the fiber is cleaned, as long as you can keep pests away you can safely store wool for many years.

Here's Emma's fleece when she was done with it, on its first trip into the warm water that begins my washing process:

START OF CYCLE, when the wool has ONLY been soaked in warm water. The dark brown in the center tray is water soluble dirt and suint, formerly in the wool that's in the tray on the right. The wool in the tray on the left is still soaking.

It's easy to imagine that Emma would want to start over with fresh growth!

Emma is a Leicester Longwool sheep, a breed known for its long, shiny, strong fiber. The beauty of the wool becomes apparent after about two hours of soaking in a series of baths, beginning and ending with plain-water versions, and with two or three in the middle that are infused with a washing agent.

END OF CYCLE after use of washing aid. Again, the tray of wool on the right has been pulled out of the center tray, and the one on the left awaits draining. You'll notice some color variation still in the wool. It's all clean, however. This cycle consisted of (1) two plain-water rinses, (2) two soaks with washing aid, and (3) two plain-water rinses. Each bath was 20 minutes long, for a total of two hours of washing, although my active involvement only occurred at each transition point, removing the upper draining tray, changing the solution, and re-immersing the fiber. All water temperatures were standard-issue from the household system, which is not set to be exceptionally hot—about 135°F.

I've described the details of my washing process elsewhere. Today I want to talk briefly about the transition from dirty to clean, mostly for fleece but also for garments.

These are both Emma's wool, from the same shearing: as shorn (dirty) on the left and after its trip through my bathtub (clean) on the right.

Washing or scouring?

Washing is what I just talked about. The process of cleaning raw wool is also sometimes called scouring, a term used in industry to include the removal of all contaminants from wool―scouring is "washing plus."

What might the contaminants in wool be? I say might because not every fleece will have all of these, and each fleece will have contaminants in differing types and proportions.

The big three, present to some extent in every fleece, are:

wool wax or wool grease

suint

dirt

Wool wax or grease is not water-soluble. It provides a protective coating, and, in general, the finer the wool the more grease it contains. It's the hardest of the three main contaminants to remove. That's the point for the sheep! It shouldn't be easy to remove!

Suint (think "sweat") is water-soluble―even in cold water. When we're washing wool, it's the easiest contaminant to get rid of.

Dirt is soil, and can be dust or mud. It can be sandy, or full of clay, or may correspond to any of the gardener's or farmer's other options, and it can be easy or hard to remove, although most of it isn't too bad. (Clay, of course, is most difficult, as it seems to be for growing plants where I live.)

Vegetable matter (or VM) is another contaminant that comes in many varieties. For hand processing, VM isn't, for the most part, removed during the washing sequence and its evaluation and management is a topic for another day. In industrial processing, treatment to remove VM occurs during the scouring sequence and involves a delicate sequence of chemical and mechanical maneuvers to get the plant material out without damaging the wool―a different topic for another day (although I talk about it some in the KDTV segment).

Some other contaminants―like dung tags, urine stains, marker dye, and insects―should have been removed before the fleece ever reached the washing or scouring stage.

What to use as a washing aid?

For the intermediate steps of cleaning wool, whether raw or spun or made into fabric, we have many choices in washing aids. I've used a number of them over the years. At this point, I have several criteria for the agent that I use. Oddly, they all start with E!

I want it to be effective, efficient to use, economical, and as environmentally benign as possible.

That means that I look for a washing assistant that

is concentrated so I don't need to use large quantities

creates minimal suds (which are hard to rinse out, wasting both time and water)

does not subject the wool to significant and potentially damaging pH shifts

works at moderate heat levels even for fine wools (in order to reduce the potential of fiber damage, and so I don't have to be boiling water or otherwise wasting energy)

cleans by bonding with the waxy or greasy particles, drawing them off the fiber and into the water so they can be rinsed away, instead of being knocked off through agitation (which can result in unintended felt, as well as more work for me)

does not involve enzymes (which continue to be chemically active even after they've been discarded) and

contains no ingredients classified as toxic.

I now use washing agents that are specially formulated for use with wool.

Dishwashing detergents and shampoos create annoying amounts of suds. I'd rather avoid the perfumes and colorants that many cosmetic products contain—and they suds a lot, too. Laundry detergents often contain brighteners, enzymes, and other ingredients I consider extraneous at best and damaging at worst. Some components of laundry detergents are actually designed to break down proteins (to get out stains like blood or egg), and animal-source natural fibers are also proteins. It is interesting to check these products' Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) or, for some items, the information in the Household Products Database maintained by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services ("Inside the Home" and "Personal Care" categories).

I wash all my natural animal fibers at between 50 and 60°C (120 and 140°F), preferably on the lower end. Wool wax, the stickiest contaminant to remove, melts at 35–40°C (95–104°F) and damage to protein fibers can occur at higher temperatures. The length of time that fiber is exposed to high temperatures, and the pH of the environment, matter a great deal. Dyeing fibers involves balancing these factors in exchange for a rainbow.

Undyed handspun Leicester Longwool samples.

________________

A practical footnote and a random fact

Footnote

Here's a quick note about washing fine wools in their raw form: When wool wax is dissolved, its chemical composition changes. If the temperature of the bath cools, the grease can be redeposited on the fiber as a scum that can be substantially more difficult to remove than it was in its original form.

Random fact

Lanolin is produced from a portion of the wool grease recovered from scouring liquid.

Two excellent resources

Simpson, W. S., and G. H. Crawshaw. Wool: Science and Technology. Boca Raton, FL, and Cambridge, England: CRC Press Woodhead, 2002.

von Bergen, Werner. Wool Handbook: A Text and Reference Book for the Entire Wool Industry. 3d enl. ed. New York: Interscience Publishers, 1963.

_________________________

Swatch knitted from yarn grown by Emma's Leicester Longwool flock mates, commercially spun.

For more on Leicester Longwool sheep, see "On the Edge: How a Handful of People Have Preserved Some Rare, Valuable Sheep and Their Wools," PieceWork, November/December 2011. Or, of course, The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook. And Leicester Longwool will be one of the breeds I'm including in the Explore 4 retreat in Friday Harbor, Washington, in March! Yes, that's why I have been washing Emma's wool. We'll be working with it. (Curious? Download Explore-4_2012 PDF)

February 4, 2012

KDTV - I've never embedded a video before

I have one more post on The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook's numbers to write, but I'm up past my ears in prepping to teach at Madrona. I have three of the five handouts prepared. I can do the slide shows while I'm traveling, because they don't need to be printed. I do have templates for the workshops I teach, but I never know what breeds will be included in the workshop materials until the last minute. So . . . the work has to happen shortly before the event.

Meanwhile, KDTV has been releasing on the web the episodes from the new series, which is 800. I recorded three segments last September, of which I've now seen two.

One is on yarns that pill. I spent a chunk of the summer knitting and "distressing" swatches. Assuming I can figure out how to embed the video, here's how that piece came out.

Another segment which I enjoyed doing is the one on yak. There's a lot to know about yak. When I researched for the book, I found a lot of great information. Some of the neatest facts ended up in this short KDTV spot.

And now I have another handout to get to work on. I'm even skipping the monthly ukulele group meeting this morning because I'm feeling far enough behind to need every minute.

(There was an unexpected addition to the Madrona schedule this week, relating to the charity-knitting event that is coordinated by Stephanie Pearl-McPhee. I can't believe I agreed to do what I agreed to do. However, it's for a good cause. It did take a full day to put together—with some work yet to come, which my daughter has offered to help with. I hope she wasn't kidding. Anyway, that set me behind on the prep for the workshops.)

Hoping the videos embed successfully. The first time I tried, I discovered that if I previewed the post, nothing showed up where they were supposed to be. While bashing around trying to figure out what to do differently, I came up with two other solutions. They both seem to work. I used different methods for each of the videos. We'll see what happens.

For series 800 I did one other segment, which I was least satisfied with when we were in the studio and I haven't seen yet. (Okay, I'll come right out and say it: I was so dissatisfied with it that I flew home thinking, "I will never again do another TV segment. On anything. Ever.") I'm writing a blog post for KDTV on the same topic (it will be up next week), so I'll feel like I've provided some useful information, which I didn't feel like I'd done in the studio situation. The producer was happy with what went on for that segment. I was not. I can figure out how to embed that video, but I'm not ready to!

In all of these, I think I look strange in studio makeup. When you meet me in person, I am highly unlikely to look like this. I made the mistake of showing the wonderful friend who cuts my hair a photo from the studio. He said, "Wow, you should do that every day!"

NO WAY. I'd rather write, spin, read, or take the dogs for an extra walk.

______

That took longer than it should have. First you have to figure out how to embed the stuff. Then you have to figure out how to make it display correctly within the blog. I didn't succeed the first time. Or the second. Final assessment: marginally okay. Giving up for now, though.

February 1, 2012

Fleece and Fiber Sourcebook numbers, part 2 - Romney

My previous post laid out the background and my philosophy for presenting the numbers describing fiber qualities in The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook. As my first example, I used a breed that was relatively simple, because it's modern and part of its definition involves very specific wool qualities: Cormo.

Although the other breeds I'm going to talk about were significantly more complicated to come up with numbers for, I was able to lay out all of the basic issues with the Cormo (which was not, of course, as straightforward as it "should" have been). So let's look at another breed's scenario. . . .

________

Example 2:

Romney

The Romney is a breed with a long history and a lot of variation. It originated, and obtained its name, in southeastern England. However, it's a successful type of sheep for both wool and meat growing and has been exported around the world. In each locale, breeders have selected for different qualities of fiber. In addition, Romney genetics include the possibility of natural colors. For large-scale industrial production, anything other than pure white wool isn't desirable, but handspinners treasure the lovely colors.

So: what types of numbers could I use to describe the Romney's wool?

As for the Cormo, the first thing I did was simply gather a bunch of data from as many sources as I could find and put the information all in one place:

As before, I sorted by geographic location, when I could tell what that was. Noticeably absent from this list is the Romney Sheep Breeders' Society in the British Isles. When I reviewed its website, there were only subjective descriptions of wool quality (although it did mention "heavy fleeces of 4 to 5kg").

There's quite a lot of overlapping data: Fournier & Fournier's Romney Marsh, The Sheep Trust (UK), and the British Coloured Sheep Breeders Association have nearly identical information. Fournier & Fournier have separate data for the New Zealand version of the breed.

Then I got out my pencil and started sketching relationships.

As the data began to come into focus for me, I started over on another sheet of paper and sketched in approximate micron-count spans for the sources that only offered Bradford or USDA numbers:

Factors I was watching for as I evaluated sources were (1) geography, (2) color (if specified), (3) date of source (since breeding goals shift with time as well as location), and (4) overall reliability of the source—not necessarily in that order!

While there's definitely overlap, New Zealand Romneys look like they have fiber on the sturdier end, and the Americans are breeding for more fineness. Fleece weights were a bit scattered.

White Romney samples, with two-ply yarn

In the summaries, I wanted to indicate the potential for variation by region. Here's what I came up with for Romney:

Staple lengths: 4 to 8 inches (10 to 20 cm)

Fiber diameters:

North America: 29 to 36 microns (spinning counts listed at 44s to 50s, but micron counts suggest 44s to 54s)

New Zealand: 33 to 37 microns (spinning counts listed at 44s to 52s, but micron counts suggest 40s to 46s)

British Isles: 30 to 35 microns (spinning counts listed at 46s to 54s, but micron counts suggest 44s to 50s)

Fleece weights: 8 to 12 pounds (or more) (3.5 to 5.5kg)

For the Cormo I gave the USDA or Bradford grades less weight, because the breed is new and part of its definition involves fleece quality and consistency criteria based on micron-count data. For the Romney, the breed's long history suggests giving the Bradford grades a bigger say in the compiled description.

Overall, wool classification is moving toward the use of more objective—i.e., micron count—measurement systems. For a number of breeds, the contemporary preference for fine wools is pushing the breeders to select in favor of the "skinny" end of the spectrum. In selecting numbers to represent the Romney, what I did was attempt to embody the effects of these forces as I saw them appearing in the data I collected.

For some breeds (although this wasn't obvious in the Romney), I observed differences in quality designations between white and colored wools. That may be because the genes that produce color in those breeds act in combination with genes that result in slightly coarser fiber, or because the breeders who are going for color like sturdier wool, or for other reasons. There's a lot we humans haven't figured out yet about sheep.

Gray Romney sample with carded rolags

_____

In some cases, the metric/imperial conversions I'm giving here are not identical to those printed in the book. My numbers are more rounded-off, since the things we're measuring aren't manufactured to precise dimensions and thinking about them in ballpark numbers is more practical. Copyeditors, of which I was one for years, sometimes get more precise in their attention to details than the material warrants. For example, for Romney fleece weights, the book says "8–12 (or more) pounds (3.6–5.4 or more kg)." I'd go with "3.5 to 5.5kg." It's as good an approximation in the metric universe as "8 to 12 pounds" is in the imperial one. It's also easy to remember.

_______

Charcoal Romney sample with "bird's nests" of hand-combed top.

Whatever its numbers, Romney is a versatile wool. It's easy for beginning spinners to manage. It also will accommodate any preparation or spinning approach more experienced hands may want to try with it.

Just as a point of curiosity, although all three of the samples shown here have well-defined, bold crimp, as is typical of Romney, each has a different type of crimp. Crimp patterns are fascinating! And way beyond what we can consider here and now.