Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 89

October 8, 2019

How to Improve Your Amazon Book Descriptions

Photo credit: tiny_tear on VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from How to Sell Books by the Truckload on Amazon: 2020 Updated Edition by Penny Sansevieri (@Bookgal).

Whether we’re talking about Amazon, or any other online retailer, book descriptions are more important than most authors realize. Too many times I see blocks of text pulled from the back of the book. In theory, it’s not the worst idea. However, it may not be the greatest idea if your book description isn’t strong to begin with, or if the book details are just slapped up on Amazon without any attention to spacing, bulleting, short paragraphs, and bold face.

We’ll discuss some ideas about book descriptions specifically, and then how to enhance your own book description for maximum effectiveness on Amazon.

Is Your Book Description Memorable Even If Scanned?

Most people don’t read websites; they scan. The same is true for your book description. When your description is visually and psychologically appealing, it invites the reader to delve in instead of click off. Huge blocks of text can overwhelm.

Even on sites like Amazon—where consumers go to buy, and often spend a lot of time comparing products and reading reviews—it’s important to keep in mind that most potential readers will move on if your description is too cumbersome. So how can you make your description more scan-friendly?

Headlines: The first sentence in the description should be a grabber, something that pulls the reader in. This text could also be an enthusiastic review quote or some other kind of endorsement, but regardless, it should be bolded. In the case of your Amazon book page, you could also use the “Amazon Orange” to set your headline apart from the rest of the text.

Paragraphs: Keep paragraphs short, two to three sentences max.

Bolding: You can boldface key text throughout the description. In fact, I recommend it. Just be sure you aren’t using boldface too much. Don’t highlight two or three sentences in bold, because it’ll have more impact if you do just one sentence or a few keyword strings.

Bullets or numbers: If your book is nonfiction, it can be very effective to bullet or number as much of your information as possible. Take key points and the “here’s what you’ll learn” elements and put them into a bullet point/numbering section that’s easy to scan and visually appealing.

Writing Descriptions for Nonfiction

It’s likely that whomever you’re targeting already owns a few titles similar to the one you just wrote. So why should they add yours to their collection? While you’re crafting your book description, keep in mind that you’re likely serving a very crowded market. You need to be precise and vividly clear about why your book matters.

Nonfiction shoppers often look for the solution to a problem. So your book description needs to zero in on what that problem likely is. Plus readers need to feel like you understand them, and they need to be convinced you’re the best person to help them work through it. If you’re a noted expert in your field, with accolades to back it up, work those in briefly, because it truly does set you apart. So do reviews by other experts in your field or industry, but keep them short and sweet—excerpts of the best parts are plenty. Save your full bio and complete reviews for the other sections that Amazon gives you.

Writing Descriptions for Fiction

Fiction is a bit tougher, because it’s easy to reveal too much, or not quite enough. For this reason, I encourage you to focus on developing your elevator pitch. Every other piece of the story anchors to that.

For our purposes, the elevator pitch is the briefest of the brief descriptions you will develop. Elevator pitches are important because there are times when you need to capture someone’s attention with a very short, succinct pitch.

And why does this matter for your book description? Because having a short hook is an excellent way to start building your book description. Elevator pitches focus on the core of your book—the one element that your book could not be without—and that’s what matters most to your reader.

When it comes to fiction, buyers have a lot of options, so your opening sentence should be the best you’ve got—because it might be the only chance you get. And don’t confuse not giving it all away with being vague. If you’re vague, the potential reader won’t experience the emotional connection they need that makes them want to find out more. So give them a story arc to latch onto and leave them needing more.

Writing Descriptions for Children’s Books

Make sure to include the intended age range. Even though you can add it in the Amazon details, I’ve had parents tell me that seeing it in the book description is incredibly helpful, because if anyone is short on time and needs help making smart buying decisions, it’s parents. It also helps a lot to let parents know right away what their child will learn, or what discussions or themes the book will highlight. While you wrote the book for children, you’re selling it to adults, so don’t oversimplify your description, thinking you’re off the hook.

Include Top Keywords

Keywords are as important to your Amazon book page as almost anything else. I’ve written a lot about Amazon-specific keyword strings that you can see on our blog: Demystifying Amazon Categories, Themes, and Keywords, but here’s a quick overview:

The term “keyword” is actually inaccurate, because readers don’t search based on a single keyword. Think instead of keyword strings.

For example, “Romance about second chances” or “Second-chance romances,” have been popular search strings on Amazon for a while now. However, by taking that sentence and inserting it into your book description, you can help boost your visibility on the site, as well as keying into your readers’ specific interest. If they’re searching for, “Romance second chances,” and they see it in your book description, it’s going to ping them with: “Oh! This is the exact book I’ve been looking for.”

That said, it’s a good idea to avoid overstuffing your book description with keywords. I recommend finding six or seven strings and using them sparingly throughout.

Update Your Book Description Often

Here’s something you may not have considered: Your page isn’t set in cement. In fact, ideally, it shouldn’t be static. When you get good reviews and awards, update your book page to reflect that. When you do your keyword string and category research every quarter (yep, put it on the list), consider whether there are any new ones you can sprinkle throughout the different sections.

Here’s a Model to Follow

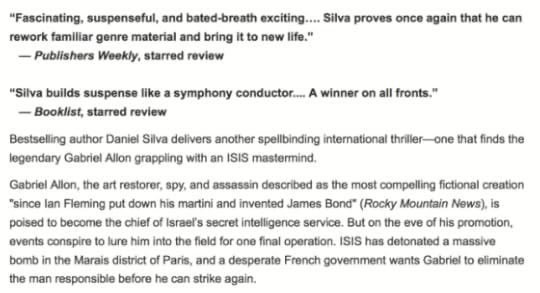

Take a look at the book description below from Dan Silva. It’s a great example of a blurb that combines great review quotes with a book description that pulls you in from the first sentence.

Book blurbs are eye candy, because people like what other people like. Even if you don’t have review quotes from highly respected or recognizable publications such as Booklist and Publishers Weekly, you should still add reviews. Just be sure to cite them correctly.

Notice how they are boldfaced to draw attention to them? And check out the second paragraph. Whoever wrote this book description inserted a review to help bolster the character description, which is another clever idea.

Notice how they are boldfaced to draw attention to them? And check out the second paragraph. Whoever wrote this book description inserted a review to help bolster the character description, which is another clever idea.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out How to Sell Books by the Truckload on Amazon: 2020 Updated Edition by Penny Sansevieri.

October 7, 2019

How to Effectively Use Live Video (Even If You Fear the Camera) to Reach Readers

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from The Bestselling Author by Amy Collins, Daniel Hall and John Rhodes, partners in Best Seller Builders (@NewShelvesBooks).

I’ll bet you dollars to doughnuts that you have within 6 feet of you right now either a smartphone or a tablet with the capability of broadcasting video (also known as livestreaming). Not only that, but chances are very good that also installed on your device is an app like Facebook, YouTube, or some other platform that would allow you to livestream.

And even if you don’t have a device, I’d wager that you own some sort of laptop or computer with a built-in webcam and microphone, which you can use to broadcast live video. The problem is, even though most of the world has this technology, very few use it and an even smaller percentage of people will use it to build their business— their platform.

But doing live video broadcasts are an effective way to engage with your target demographic, get them to know and like you, become your fan, and eventually buy from you. As I write this, the big players in broadcasting live video are the aforementioned Facebook and YouTube. However, by the time you read this that may well have changed. Platforms come and go. That is why I am somewhat platform agnostic because I know that there will be a platform where you can broadcast and where a large segment of your target demographic hangs out.

Before we go further, I want to address the topic of fear of appearing on camera. Actually, fear is quite natural, but here’s the thing: Like everything else, you’ll get better by doing it. And people watching are not expecting broadcast television quality. The fact is, if you’re real and not slick you are much more relatable.

Also, keep in mind that if you do a livestream and mess up royally that you can always end the broadcast and delete the video. So really there is very little risk and you are in control.

But the reason you want to livestream is to give people in your audience a chance to fall in love with you and your message. So honestly, if you approach doing live video from the standpoint of being of service to your audience, they will see it and appreciate it regardless if the presentation has a few warts.

Be that as it may, it is still a good idea to prepare for and have a plan for each of your broadcasts.

Preparing to Livestream

As we have already pointed out, you probably already have access to technology with which to “go live” with something like a smartphone, tablet, and/or laptop. And these are great to start out with but in the future, you will probably want to upgrade your microphone. For example, if you’re going live with an iPhone/iPad or Android device, I really like my iRig HD 2 microphone, which sounds great and is relatively inexpensive on Amazon.

In addition to your microphone, you will always look more pro if your broadcasts are well lit. Once again, if you are on a device, a simple rechargeable ring light would make a great addition to the tool box. These lights are cheap, stay illuminated a reasonably long time, and help make you look great.

If you don’t have a ring light or other lighting, then I suggest you set yourself up in front of a window to take advantage of natural light or, alternatively, do your broadcasts outside.

For the most part, platforms like Facebook and YouTube make it easy to go live directly from their apps. Simply tap a button and the app will ask for permission to use your device’s camera and microphone, and you are off to the races. The big difference between them is that what you broadcast live on Facebook belongs to Facebook. What you broadcast live on YouTube is still your content owned by you.

If this is important to you, then you might want to make your choices based on current agreements. Always check the agreements and rights clauses when starting to broadcast on a platform.

If you’re on a laptop or desktop computer, while you can certainly go live directly from Facebook or YouTube, you would definitely up your game with cool, paid third-party services like BeLive.tv or Zoom. The advantages of these services are that you can schedule your broadcasts, you can use lower-thirds graphics for your name, and you can interview up to three other people with a split screen (which will be useful if you decide to interview others in your niche). The big disadvantage is there is a monthly fee of $20 to $50.

While these services will certainly make you look more pro, I would recommend not starting with them. Just launch with what’s free, and as you get more proficient and build an audience, then you can switch over if you like.

Planning to Livestream

A big criticism of livestream videos is that many broadcasts are frankly boring and meandering and there is no clear destination. You are, after all, vying for attention. And let’s face it, there is no shortage of distractions. Accordingly, to honor your viewer’s time and attention you must have a plan for your livestreams. That is, each livestream should have a goal or intention.

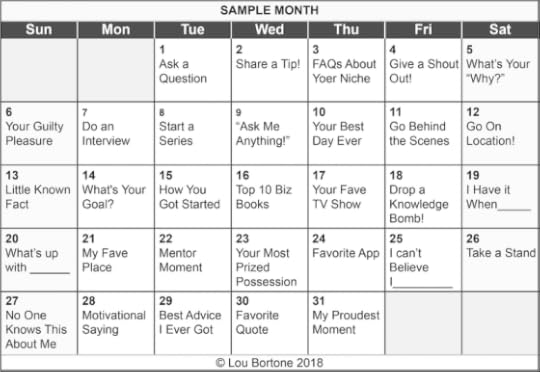

My friend and video trainer par excellence, Lou Bortone, solved this problem. He devised a brilliant sample calendar with ideas of what to cover on your livestreams:

Of course, you don’t have to do all of these topics. Pick and choose those you like or use it for inspiration to create your own. The key is to have a plan and intention for each livestream.

Additionally, your livestreams don’t have to be long, 60-minute affairs. In fact, you want to strive to be succinct on one hand while encouraging audience interaction and questions on the other. Because let’s not forget that the whole reason of doing livestreams is to build your platform and one of the key ingredients to that is including a call to action. One such call to action should be something like: “Get your questions in the chat now” or “Don’t quite understand this concept? Then hit me in the chat with your question and let’s get this cleared up for you.”

Of course, at the end, and during your broadcast, if appropriate, you should include a call to action to go download your free gift, check out a new blog post or podcast interview, etc. The point is, you must get comfortable with telling people what you want them to do. And you’ll train your growing platform to do exactly this if you’re consistent about calling them to action. The most effective platform builders I know have become masters of this.

Another hallmark of great platform builders is consistency. So pick a day and time to do your broadcast and do your level best to stick to it. I recommend starting with at least one livestream per week. Or try more frequent broadcasts if livestreaming really appeals to you. Whatever you decide, stick to it and you’ll train your audience to know that you are consistent and reliable. Further, these livestream videos can be downloaded and re-used.

Yes, there are intricacies and nuances to livestreaming effectively but the potential rewards are significant. There is yet an additional benefit to getting in a habit of livestreaming and that is it will help you become a better communicator. You’ll get better at being more precise in your verbal communication skills. And that will result in you being understood more quickly with less effort on the part of your audience. This one factor alone will serve to build your platform.

Yes, there are intricacies and nuances to livestreaming effectively but the potential rewards are significant. There is yet an additional benefit to getting in a habit of livestreaming and that is it will help you become a better communicator. You’ll get better at being more precise in your verbal communication skills. And that will result in you being understood more quickly with less effort on the part of your audience. This one factor alone will serve to build your platform.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out The Bestselling Author by Amy Collins, Daniel Hall and John Rhodes of Best Seller Builders.

October 4, 2019

Sure, Write for Yourself—But Know Your Reader When It Comes Time to Sell

Photo credit: Singing With Light on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

At writing conferences and industry events, agents and editors alike are fond of saying you should write what’s in your heart, or what you most want to write. Don’t pay attention to trends or what sells, they say. Write your story, even if it’s out of style.

While that may be sound advice if you’re focused on the creative process, once the writing is done, if you haven’t the faintest clue about your readership, you’ll run in circles trying to market and promote your work. Of course, you can rely on a publisher or a marketing professional to do the work for you, but that can be risky as well as expensive—and not always an option.

Even you didn’t consciously have a reader in mind while writing your book, you’ll have to research or identify one once it’s on the market. But ideally, your concept of your target reader (or to start, the genre you’re working in—which equals a findable audience) should be clear from the start. In my latest column for Publishers Weekly, I discuss: No Clear Readership, No Clear Sales.

October 3, 2019

How to Convert Book Readers into Email Subscribers

Photo on Visualhunt

Today’s guest post is by Dave Chesson (@DaveChesson) of Kindlepreneur.

Obtaining readers for your book is hard enough. It takes intentional marketing strategies, review management, and other techniques to build an audience. But how do you take a stranger who bought your book on Amazon or received a copy from a friend and get that person on an email list where you can stay in touch with them?

This is a question that plagues all writers, but one proven way to do this is through reader magnets.

What’s a Reader Magnet?

Reader magnets are free resources you create to incentivize book readers to join your email list. As you can imagine, this is easier said than done. And some approaches work better than others. We’ll explore several strategies for converting readers into subscribers, with some that work well for fiction and others that are better for nonfiction. We’ll also look at examples of how authors have used these strategies successfully.

But before we do, let’s answer the question I bet a lot of you are asking.

Where Can You Tell Your Readers About Your Reader Magnets?

Short answer: In your book!

At the end of his popular book Ego Is the Enemy, bestselling author Ryan Holliday has a page titled “What Should You Read Next?” which says:

I have prepared for you—my book-loving reader—a full guide to every single book and source I used in this study of ego. I wanted to show you not just which books deserved citation but what I got out of them, and which ones I strongly recommend you read next.

He then invites readers to visit a specific URL and join his email list, promising to send them, “a collection of my favorite quotes and observations about ego—many of which I couldn’t fit in this book.”

Smart, right?

And you don’t have to wait until the end of the book to offer a reader magnet. Some authors do it before their first sentence. It’s smart not to wait too long — because most people don’t read a book from cover to cover.

In his New York Times bestselling book Launch, Jeff Walker ends his introductory chapter with this sentence:

One more thing: Make sure you go to [URL] to get all the extra training videos and resources that go along with this book.

At the end of the second chapter, he invites readers to visit his website to read the full case study of a story he just referenced. He does that again in the fourth chapter with a different case study—and one more time in the thirteenth chapter. He closes the book by again inviting people to sign up for supporting resources he created just for readers of the book.

Now, you might be thinking, “Doesn’t this get annoying for readers? All these reminders to join the email list?” I say no, and here’s why.

In the examples I just mentioned, the authors strike a smart balance. The freebies Walker and Holliday offer relate directly to what people are reading; due to their length, they don’t really belong in the book. This way, readers don’t feel shorted or spammed, and they get an opportunity to go deeper if they want to.

Now that you get the big picture, let’s look at some ideas for nonfiction reader magnets, then we’ll talk about fiction.

Nonfiction Reader Magnet Ideas

Nonfiction reader magnets are usually easier to create than their fiction counterparts. That’s because authors of nonfiction can easily guess what their readers might be interested in.

When a reader picks up a nonfiction book, it typically means they want to learn something. They’re trying to create a change or transformation in their own life. And just to be clear, this doesn’t only apply to self-help books. Even in the case of memoirs and autobiographies, readers are drawn in by the opportunity to learn and grow.

This realization can generate ideas for free resources you might create. Let’s look closer at two specific examples.

Idea #1: Create a Free Online Course

When it comes to using courses as a content upgrade, Pat Flynn of SmartPassiveIncome has mastered this technique. In his wildly successful book Will It Fly, Pat created a free video course as a content upgrade for everyone who purchased his book.

First, Pat used the course as a reader magnet to convince book buyers to join his email list. Then, once people were enrolled, he used the free course as a launch pad for a premium course people had to pay in order to access. This allowed him to not only grow his email list, but his revenue as well.

If the idea of creating a course sounds intimidating, remember that as an author on your chosen subject, you’re already a content expert. Platforms such as Thinkific and Teachable make creating online courses surprisingly simple, at least from a technical standpoint. Plus, the video component of a course can help your readers get to know you, which deepens the connection moving forward. That said, there is a simpler approach.

Idea #2: Create a Free Ebook

Ebooks are easier to create than video courses, and often easier to deliver. If creating an online course isn’t your thing, consider putting together an ebook with additional information the reader will want.

Fiction Reader Magnet Ideas

At first glance, fiction reader magnets may seem more difficult to create. However with a little bit of creativity, writers of fiction can still develop compelling freebies.

There is one big difference between fiction and nonfiction, however. In storytelling, you want your reader to feel immersed in the world you’ve created. You don’t want to “pop the fictive bubble,” as novelist and writing coach Ted Dekker puts it. For this reason, it’s smart to only mention reader magnets outside of your story, so as not to distract from the tale.

That said, in writing, rules are made to be broken, and if you have a map of your world, a genealogy, or some other resource you think readers will be dying to get their hands on, you can certainly ignore my advice. Here are two ideas for fiction reader magnets.

Idea #1: Use The Kobayashi Maru Tactic

Although I cannot take credit for the method, I have officially dubbed it the Kobayashi Maru Tactic.

For those of you unaware, I am a huge Sci Fi fan. And that extends to Star Trek. In Star Trek, the Kobayashi Maru was a starship mentioned as part of Captain Kirk’s impossible test. But, even though the name of the ship was mentioned throughout the TV series, the ship was never revealed. It just grew within the readers’ minds and became an unseen part of the story. Only when the movie was released did viewers get to see the Kobayashi Maru.

You can use this tactic to create reader magnets just like author W.H. Lock did. In one of his stories, Lock wrote a character who was always greeted by, “I thought you died back in Cleveland.” But here’s the thing. Lock never revealed what actually happened in Cleveland. Not until he offered it to readers as a short story, in exchange for signing up for his email list.

Do you have a hidden chapter, side story, or alternate ending your readers might enjoy? Tell them about it, and give them a chance to join your email list to get it.

Idea #2: Create Supplemental How-Tos or Further Reading Related to Your Book

Suzanne Woods Fisher is a well-known author of historical Amish and Quaker fiction. Her readers find that period and lifestyle fascinating. So, for one of her book launches, she created a guide explaining the difference between Quakers and the Amish, as well as beautiful Quaker quotes designed to print and display.

You can also create supplemental material that pulls your story into reality. Perhaps one of the best examples of this is with the Harry Potter series. Throughout Rowling’s books, the characters gobble down delicious treats, one after the other—leading to fans creating Harry Potter-inspired recipes and cookbooks.

Although these recipes weren’t specifically written by JK Rowling, they could have been. And you can use a strategy like this to create your own reader magnet and offer it as a free add-on to people signing up for your email list.

Perhaps you’ll offer some barbecue recipes to allow readers to experience, in their own homes, the fare featured in your Western romance. The ideas are endless.

Idea #3: Give Away a Preview of Your Next Book

Here’s one final idea that’s worth a quick mention. If you’re writing a series, or if you know what your next book is going to be about, you, as a self-publisher, can give away the first one or two chapters from your upcoming book—along with the promise that you will notify readers when the book is available for purchase. This can be an effective reader magnet because it promises more action and adventure at a time when readers are craving just that.

Parting advice

You work hard to attract readers. You want that hard work to grow your community and raise your baseline potential for future books. So make it easy for them to stay in the loop.

Each of the methods I’ve shared has a degree of creativity to it. Yours will require some creativity as well. The big idea is simply this: What’s something your readers would love to have that you can create and offer for free? Once you know the answer to that question, you’ll be able to level up your book marketing.

October 2, 2019

Beware of Blending One Too Many Literary Devices

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

[Stated Genre: Historical/Magical Realism (written as memoir)]

CHAPTER ONE

The Southwest Missouri Ozarks

December 30, 1852 — As Told to Me by Miss Jesse Settle

Milksnake Hollow glides lithe as a cottonmouth between Grit’s Hill and Prophet’s Mountain, following the course of Deer Lick Creek. Our nearest town of any size is Springfield, a gateway to those lands where prosperity is more than a far-flung wish.

Come with me to the Hollow if you will, Dear Reader, to an old four-square cabin constructed of logs gone gray, and, within that cabin, a woman—my mother, Yvette Creed—writhing upon her bed, where I am soon to be born, a child of prodigious lungs and a tight grip.

Her husband, Parnell Thaddeus Creed, planned to celebrate my birth with a jug of moonshine, but on that day, whether due to poor planning or lack of moderation, he was down to the last sip in his last jug.

When the midwife came from the bedroom, Parnell was sitting in the stronger of the two kitchen chairs, a chaw of tobacco tucked inside his lower lip. The midwife was Cherokee, dark as river clay. Folks called her Miz Settle. Her Christian name was Jesse.

“Ya gotta healthy daughter.”

“A daughter? Sheeit.” Parnell released a gob into his spit can. “How’s my wife?”

“Fine. Done a good job, your wife.”

Miz Settle washed her hands in the basin atop the dry sink then turned and fixed my father with a hard stare.

“What?”

“Midwives get paid, Mr. Creed.”

“You deliver me a daughter and still expect money? And here I am, tryin’ to make a livin’ upon a rock acreage, half of it vertical.”

“Where you live ain’t my problem. Keeping my body and soul together, that be my prime concern.”

“You’re a greedy one, Miz Settle.” He rubbed his forehead with the heel of his hand. “How about a chicken? Yvette’s got a fine red-feathered hen. Lays good.”

“Not a pullet?”

“Well … about one year old. Almost full growed.”

The midwife sat down in the other chair. “All right then. We’re even.”

First-Page Critique

All art comes down to choices. With every choice we make, we eliminate countless others. Which is all to the good, since in art as in life too much freedom is not only burdensome, more often than not it results in chaos.

This first page offers a blend of superb writing and some big choices yet to be made.

Let’s start with the good writing, obvious from the first sentence: “Milksnake Hollow glides lithe as a cottonmouth between Grit’s Hill and Prophet’s Mountain, following the course of Deer Lick Creek”—a sentence so grittily specific you can mill grain with it. With this muscular, musical sentence (the author has a very good ear), we are thrust deep into Milksnake Hollow, a setting as yet untamed, or anyway not yet completely tamed, a place of natural beauty, but also—as suggested by the snake in its name and the serpentine metaphor that comes with it—foreboding.

From there we’re taken inside the “four-square” cabin in which, accompanied by her husband and a Cherokee midwife, a woman is about to give birth to the daughter who will eventually become none other than our narrator.

And here we confront one of those big unmade choices, namely: who is this narrator? From what vantage point in time and space does she bear witness to and report these events? To whom does she report them? Regarding these questions, what choices has our author made—or not made?

As a matter of fact, I hadn’t yet read that fine first sentence before encountering another big, yet-to-be-made choice, which is why—though I don’t usually do so—I’ve included the author’s stated genre, or genres. No sooner did I see the words “Historical/Magical Realism” slashed together than I wondered where the common denominator of those two genres—one based upon a factual historical record, the other antithetical to literal, let alone historical, facts—lies.

Not that those two genres can’t get along. Many works of magical realism have some historical basis, including the most famous, Gabriel Garcia-Màrquez’ One-Hundred Years of Solitude, whose setting, Macando, a magical (and thoroughly fictional) “city of mirrors,” reflects the historical Columbia surrounding it, a newly independent nation rife with rigged elections and civil war. That said, no one would call Màrquez’ novel “historical fiction.”

To complicate things further, this historical/magical realism novel has been “written as a memoir.” Which is it? Novel? Memoir? Faux memoir? Aren’t all fictional first-person narratives faux memoirs? Even if we accept that a work of magical realism can embrace a historical record, or that a work of historic fiction may contain elements of magical realism, and that said work may assume the form of a memoir, we’re still not out of the woods—or out of Milksnake Hollow, as it were. The chapter subheading goes on to tell us that what we’re about to read is “As Told to Me by Miss Jesse Settle.” With that the waters are thoroughly muddied, for by definition a memoir is told by the person whose memories are its subject (The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, by Gertrude Stein, is no exception: it’s not a memoir, and is written in Alice B. Toklas’ voice).

Now I’m deeply confused: a confusion shared, apparently, by the same talented author who penned that fine first sentence, and whose subsequent dialogue is swift, witty, and says so much about the characters who speak it. But talent must be controlled; in fact the greater the talent, the more constraint it requires, lest its beneficiary end up with something that, wanting to be all things to everyone, ends up being nothing to nobody.

In this case we have an author whose perfect ear for diction and dialogue is matched by her love of devices: indeed, she can’t bring herself to forsake any of them. How else explain a narrator who isn’t the narrator, but someone to whom the narrator has told her story, notwithstanding that, as far as this first scene goes, she was in no position to recall it, having yet to breach her mother’s birth canal? Or that Lawrence Sterneian “Dear Reader” that adds yet another wrinkle, a metafictional one, dragging the reader into this already murky mixture, to where we can scarcely see the forest of this strong opening through all those literary-device trees.

And yet with very little work this opening can be rescued from its author’s wish to avail herself of every tool in her kit. I say ditch the Dear Readers and all other forms of direct reader address (“Come with me…”). Let the narrator narrate her own birth; fine; but not as told to or by anyone else. Write a novel in the form of a memoir, but know for certain it’s the former and not the later. And blend genres to your heart’s content, but only once you’ve realized which genre rules the roost, and which are subordinate. Do that, or make big choices of your own, but choose. And this opening that reads so well despite its befuddling blend of genres and devices will read that much better.

A final nitpick concerning the otherwise first-rate dialogue on this page. Like so many authors these days, this one appears to have gone out of her way to avoid using “said.” Especially among young authors there appears to be an outright injunction against that innocent word, as if avoiding “said” were among an author’s greatest contributions to literature while furnishing irrefutable evidence of stylistic virtuosity. Whoever tells you to avoid using “said” may be your good friend but should not be your editor. “Said” is a perfectly good word. It melts in the mouth of dialogue, so the reader scarcely registers it. Meanwhile not only can it make dialogue easier to follow; it can make it read better, too. Judge for yourself the efficacy of the added “said” here (in bold):

Miz Settle washed her hands in the basin atop the dry sink then turned and fixed my father with a hard stare.

Miz Settle washed her hands in the basin atop the dry sink then turned and fixed my father with a hard stare.

“What?”

“Midwives get paid, Mr. Creed.”

“You deliver me a daughter and still expect money? And here I am, tryin’ to make a livin’ upon a rock acreage, half of it vertical.”

“Where you live ain’t my problem,” said Jesse. “Keeping my body and soul together, that be my prime concern.”

“You’re a greedy one, Miz Settle.”

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

September 25, 2019

Point of View: Moving From Plural Perspective to Individual Perspective

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

To the Swedish team: With the improved performance against all Service Level Agreements (SLAs) for Squadster, the management at Oros award you with a special night of pizza and delight. Each employee can choose a 40-centimeter pizza to share and one drink for free! Meet at 18:00 at Fast Pizza Italian Food restaurant. There are distractions including Darts and sports television! RSVP to Levi Bakker!!

September 18, 2019

Vivid Storytelling Requires Delivery of Experience, Not Just Information

Photo credit: WabbitWanderer on Visual Hunt / CC BY-SA

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

In the morning, the soldiers will pack the women prisoners into cattle cars and send them away. A lieutenant stands atop a crate and snaps at the prisoners to form a line for rations. When a pained cry rises from the crowd, pleading with the officer as to where the army is sending them, it goes unanswered.

Lee Palmer muscles to the front of the line in case supplies are limited. Someone elbows her ribs. There’s a fierce yank on her braid. Despite the yelling and crying of the women, she overhears a whisper that their destination is Nashville. This would not be so wretched, she thinks, there are worst places to go.

Lee reaches the two privates who shove rations across a wide table in a mechanical, hurried fashion. Lee seizes the parcels and forces her way back through the crowd so she can examine her food in safety where no greedy hands will tug it free. Twenty ounces of salted pork in a cloth, hardtack crusted with weevils, three cans of peas. This is too much food for Nashville, she thinks. The army is not generous with its food. She closes her eyes as she remembers the railroad maps of this region. Travel time to Nashville with stops in Chattanooga and Murfreesboro: two weeks. This was before the war. Perhaps there is no longer a railroad to Nashville. For all Lee knows of the outside world, there may no longer be a Nashville.

Lee sits on the dirty wood floor amongst the other prisoners, but despite their shared condition, despite her years at the mill alongside them, she is not invited into their little circles of panic.

Nancy, her only friend, hops over the outstretched legs of an elderly woman, her hands clutching her measly rations to her chest like family heirlooms. She settles in beside Lee, and though Lee can tell her friend has been crying, she has to say it.

“They’re sending us somewhere far,” Lee says.

Nancy’s tears are immediate and furious. She curls up beside Lee, head on her shoulder. Lee strokes Nancy’s hair since that’s how Mama calmed her after a nightmare, but it does little to soothe Nancy.

They were four hundred women in total. All of them poor. Many without a full set of teeth, many without shoes. At the Roswell Mills, they spun cotton for rope and uniforms and stitched tents and stretchers in a room flush with hot cotton fibers in exchange for a place to sleep and one hot meal a day.

When the Yankee Army came to this corner of Georgia, it found little resistance. The Yankees seized the Roswell Mills without firing a contemptuous shot.

The only gunfire came from overzealous privates who shot out the windows of the barracks after the officers told the women, gathered in the center of the property, they were under arrest.

The Yankees then brought the women—now prisoners—to Marietta to wait in the abandoned military college there till someone with authority decided what to do with them. Now they know. They’re to be deported.

Lee continues to brush Nancy’s greasy hair while her mind reels.

Theo, you promised, she thinks. You said you would come back for me.

They’re sending us away. You need to come back before it is too late.

First-Page Critique

Though I know which side won, I’m no expert on the Civil War. And though I’d heard of the Roswell Mills, it was only after reading this first page of a work of historical fiction that I did some digging to learn the role it played in that terrible conflict. Located north of Atlanta near the Chattahoochee River, the cluster of mills produced textiles from cotton grown on nearby plantations. When the war started, the mills turned to producing a fabric of a uniquely drab color known as “Roswell Gray” and made into Confederate uniforms. On July 5, 1864, General Sherman’s troops seized the mill and ordered all four hundred of its employees—mostly women and children—arrested for treason and sent by train to a military institute in Marietta, where they were held for a week before being expelled to points north. During that week, many of the women were subjected to assaults by Union soldiers assigned to guard them. Subsequently their fates were no better. Left to their own devices, without money, contacts, or any prospect of employment, many starved to death.

That’s the background of this first page. But unless readers know it, they can’t be blamed for thinking they’re dealing with entirely different “cattle cars” in an altogether different war. That was my experience on first reading this page, at least up to the word “Nashville” toward the end of the second paragraph, by which time my imagination had already conjured a quite different scene. Possibly this was the author’s intent: to achieve a sort of lap-dissolve in the reader’s mind whereby an infamous twentieth-century wartime horror is supplanted by an obscure, nineteenth-century one. But though such a dissolve effect might be extremely effective on film, where it can be choreographed to within a fraction of frame, on paper it’s a recipe for confusion and the dismay and resentment bred by it. Unless absolutely warranted by the material, my general rule is never confuse your readers.

Confusion aside, this little-known episode of the Civil War is terrific material for a historical novel, and overall the writing on this first page is more than competent. Still, there are ways in which it can be improved.

Let’s start with the first paragraph, written from a non-specific, neutral perspective. Who sees the Lieutenant? Who hears that “pained cry”? Whose experiences are given to us here, from what vantage point? Answer: that of a colorless narrator located everywhere and nowhere. We may as well be getting not experiences, but information. The difference between the two is the difference between bland and vivid storytelling.

In fact, someone must be hearing and seeing these things, and that someone, we soon come to realize, is the “Lee Palmer” who “muscles to the front of the line in case supplies are limited.” With that first sentence of the second paragraph a clear perspective is engaged. We are no longer reading information; we are sharing an experience.

We would share it even more solidly were the emphasis of the sentence not misplaced, with the subordinate clause serving as its punch-line, and the words “in case,” which convey motive rather than action, replaced by an active verb. The sentence would be stronger still if we had some idea who “Lee Palmer” is: not an officer or a soldier—in fact not a man—but a female prisoner of the Union Army. (On a side-note: it was not until after the Civil War that, in the Northern states, anyway, and for obvious reasons, the name Lee became fashionable.)

“Knowing how limited supplies were, Union prisoner-of-war Lee Palmer muscles her way to the front of the line.” Now not only do we have some idea of who Lee Palmer is, we know we’re in not World War II but the Civil War, so we can more-or-less form an accurate picture of the scene in our minds. And isn’t that the point of fiction, to create experiences for the reader precisely and clearly, so that the experiences become theirs? To that end what role does confusion play? Unless the experience is confusion, none.

This is why properly engaging POV is so crucial, since things are always experienced by a particular sensibility operating from a specific vantage point, rather than generally from a neutral, disembodied perspective.

The rest of this first-page engages its protagonist’s experiences tenuously and fitfully. “There is a fierce yank on her braid.” That’s half or two-thirds of Lee’s experience; it would be the whole shebang if the sentence were, “Someone yanked on her braid” or “She felt a tug on her braid.” In the next sentence Lee “overhears a whisper.” But to overhear a whisper you have to be close enough to the source to both hear and see the whisperer, yet the source of the whisper is unidentified, as if it doesn’t matter, or—less likely still—as if Lee Palmer doesn’t care, though she certainly would, since those whispered words may seal her fate.

The next paragraph (“Lee reaches the two privates…”) is the first one that thoroughly and consistently engages Lee’s experience, so by the time we read “The army is not generous with its food,” we read it not as bland information, but as Lee’s perspective on things. Things continue well through the next paragraph, until we get to the fifth paragraph and Nancy, Lee’s “only friend,” who “hops over the outstretched legs of an elderly woman.” “Hops” is the verb, but it should be “sees” or “watches,” and it ought to pertain to Lee’s experience, not Nancy’s. “Lee sees Nancy, her only friend, hopping over the outstretched legs of an elderly woman.” See the difference? As written, either the sentence engages Nancy’s experience, in which case it’s a jarring point-of-view shift, or it engages the author’s perspective, which is as good as none at all. Point of view is the difference between the author and the narrator.

Two sentences later we read that Lee’s stroking of Nancy’s hair “does little to soothe Nancy.” I believe it, but it’s information. Whose information is it? Lee’s. How does she know it? We don’t know, but we can guess. Perhaps by the look on her friend’s face as Lee strokes her hair, or by the tears still welling in her eyes, or the trembling of her shoulders. Those may be Lee’s experiences, the concrete evidence from which she derives her information. Instead of giving us Lee’s information, give us that evidence; let us draw conclusions from it.

Similarly, Lee can’t possibly experience “400 women in total.” What she experiences is a throng of women. She might conclude—with remarkable precision—that they total 400; but the more likely explanation for that figure is an author injecting her own awareness.

Similarly, Lee can’t possibly experience “400 women in total.” What she experiences is a throng of women. She might conclude—with remarkable precision—that they total 400; but the more likely explanation for that figure is an author injecting her own awareness.

Reread the rest of this page and see for yourself which moments authentically engage Lee’s experience, and which fail to do so. Then imagine, with her experiences thoroughly and consistently engaged throughout this already striking and gripping first page, how much more striking and gripping it would be.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

September 17, 2019

7 Common Mistakes in First-Time Memoir

Today’s guest post is by developmental book editor Jessi Rita Hoffman (@JRHwords).

1. Confusing Memoir with Autobiography

Writing a memoir is not the same as writing an autobiography. In an autobiography, you typically start at the beginning of your life and record all the details you can remember, chronologically. In a memoir, you take a slice from your life—a particular theme or lesson or flavor of experience—and write about that, pretty much ignoring the rest.

Famous people, like celebrities, can write an autobiography and manage to sell it successfully because the public is already fascinated by them. Everything about the author is considered interesting, because the author is perceived as interesting. For the rest of us, however, selling an autobiography is in the same category as winning the lottery or getting struck by lightning.

That’s because even if we’ve had a fascinating life, it probably won’t be fascinating enough to the public at large for them to want to read every detail of our experience. There are too many other books out there vying for people’s time and attention.

That’s why authors with a special story to tell generally write memoirs, not autobiographies. They focus on the aspect of their life that is most unusual or fascinating, and structure the book around that. If the story is unusual or fascinating enough, their book will find an audience.

2. Telling a Story Already Told

That brings us to the second mistake people make when attempting to write and market their personal story: often they don’t realize that their story has been told before, by other people who have experienced the same thing. Growing up with an alcoholic mother or father or going through a divorce, for example, are stories which countless other books have already explored.

If you want people to read your memoir, it must be unique enough to stand out amidst the sea of other memoirs. Not only that—it also must sound unique in your marketing materials (including your query letter to agents). Agents don’t want to represent a book they think is a rehashing of books already written, because they know they can’t find a publisher for that. Publishers are interested in buying unique memoirs only, because that is what the public wants to buy.

3. Shoehorning Several Books into One

Most memoir manuscripts that come across my desk from first-time authors are massive conglomerations of two or three books, all shoehorned into one. They want to write about their paranormal experiences, but they also want to write about the funny things their child did growing up, and also about their lifelong struggle with ADD, at the same time sharing their heartfelt political opinions.

Any one of those could be the topic for a book, but trying to combine them all into one memoir is a mistake. Different audiences will be interested in those four different topics. If someone buys the book hoping to read about paranormal experiences, and instead finds 75% of the book filled with mommy stories and other material they have no interest in, they will feel you, the author, have cheated them, misrepresenting what the book is about in your advertising, and selling them one quarter of a book—one quarter of what they paid for.

A memoir needs to be focused on one theme, or one life lesson, that has wound its way like a bright thread through the experiences of your life. Yes, you have many such threads, many lessons that make up your life experience, but don’t try to include them all in one memoir. Pick one—the most important one to you—and write about that, stoically ignoring the others, which will vie for your attention and writing space like insistent ghosts at your shoulder. When you sit down to write, tell them no, and stick to it!

Most writers don’t realize that they typically have two or three potential books kicking around in their head, asking for written expression. They mistakenly try to put them all together into one book, which causes all of the stories to fail. Mentally separate the themes that you feel compelled to write about, and regard them as distinct and separate books. Start out writing just one of them. Save the others for later, if you truly believe they are unique enough to be marketable.

4. Confusing Memoir with Journaling

Writing down our experiences has the effect of helping us make sense of our own lives. That’s why journaling has become such a popular therapy and self-help tool. There’s real, personal value in contemplating the details of our lives and setting them down on paper. Writing forces the mind to reflect, to organize experiences, to distill and extract the meaning stored in our memories.

But writing a memoir is something else entirely. When we journal, we write for ourselves. When we memoir, we write for others. Other people aren’t interested in all the details of my personal life story the way I naturally am—close family may care, but not strangers. Strangers come to read a memoir in hopes it will somehow shed light on their own life experiences. This is an important distinction.

When you have lunch with a friend, you don’t tell them every minute detail of your life for the past several weeks. You select from among your experiences those you suspect they will resonate with, those they will find interesting, challenging, or amusing. You would bore them to tears if you didn’t mentally edit what you talk about. In the same way, a reader will be bored to tears if you indulge in writing about things that have special interest only to you.

Think about who you are writing for, who your target audience is, and always keep them consciously in mind while you’re writing. Don’t allow yourself the luxury of randomly writing whatever comes into your head, or you’ll veer off the pavement and into a ditch.

Try to imagine the reader sitting in front of you, and always write as if they were listening, as if you were sitting together sharing a cup of tea or coffee. Sometimes it helps to think of one real person you know in particular, and imagine yourself writing the book to them. The important thing is to keep your readers in your mind whenever you sit down to write. That will keep you driving within the lines, steering the book where it needs to be going.

5. Overdoing the Family History

Most memoir manuscripts I come across get into irrelevant side trips regarding family history, local history, or other topics of interest to only a very small audience. If you’re writing your memoir only as a gift to your family, and don’t intend it for public consumption, then by all means delve into the details of your family’s past. Write down everything you know and remember. Your loved ones will thank you for it, and you will have preserved the family stories for future generations.

But if you’re writing your book with the intention of selling it, with the goal of reaching a broader audience than just your kids and grandkids, stick to your topic and don’t get caught up writing about how your great-grandmother met your great-grandfather at the meatpacking plant (of which you give the history) and then settled down to raise nine kids, all of whom you individually name, along with birthdates.

Readers want to read about the life theme you advertised your memoir as exploring, so focus on that subject and don’t get distracted. Like journaling, writing family history has its place—a very respected place—but that place is not the domain of memoir writing. Memoir is a different genre entirely.

6. Chronology Mismanagement

Chronology in a memoir will be problematic when it errs in either of two directions. On the one hand, readers get whiplash when an author jumps forward and backward in time often and without good reason. Amateur writers sometimes do this, thinking it makes their writing seem “stylish.” But unless you have a good reason to relate events out of order, you risk confusing the reader as to when the various incidents occurred.

On the other hand, it’s a mistake to slavishly narrate events in the order they happened when a different ordering may accent the story’s most important events, creating questions or suspense in the reader.

A good technique is to open the story with an incident that focuses the theme of the memoir, after that starting the story at the beginning and continuing with scenes chronologically (unless you have good reason to do otherwise).

For example, you might start a memoir about your lifelong struggle with ADD with the scene where you lost your first job after college because your employer thought your learning style meant you were slow and stupid—an event which made you doubt yourself and almost give up on your future. That could be your Chapter One, followed by a chapter where you switch to your first day of school, where you also confronted ignorance about your disability, this time on the part of your first-grade teacher. Then you could continue chronologically after that.

In this example, by starting the book with the crisis event that caused you to seek help and self-understanding, you create a need in the reader to keep on reading, in order to find out what happened. Don’t make the mistake of ending the first chapter by revealing how you worked your way out of the problem, or you’ll ruin the suspense. Save the resolution for the end of the book, where you circle around back to the crisis event and tell how you rose above it.

7. Writing Libel

If your memoir contains stories of villains and people who have wronged you, you have to be really careful, or you could get sued. Contrary to what many writers think, using fictitious names is not enough to protect you. I’ve written a whole article about the libel problem, which you can find here.

When in doubt, consult a lawyer. That can be expensive, but check out the various services online, such as Legal Shield, that allow you to speak with a lawyer for a small fee. Talk to a defamation attorney, not just a general attorney, to ensure you’re getting accurate information. Legal Shield allows you to specify the kind of lawyer you wish to speak to, and if you don’t like the person assigned, you can ask to speak to a different lawyer afterwards. I’ve had good luck with Legal Shield and have used their services for various matters over the years.

With the above information, you can avoid the major pitfalls involved in writing a memoir. When you’ve given it your best effort, pass it by a qualified developmental editor before contacting agents. You only get one shot at impressing them, so make sure that what you’ve written passes muster.

September 16, 2019

3 Critical Things You Won’t Learn in an MFA Program

Today’s guest post is by author, editor, and educator Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire).

The pros and cons of an MFA in creative writing are widely debated: on one hand, such programs offer students the opportunity to work with accomplished authors, whose expertise (and endorsements) could make all the difference in publishing their first book. On the other hand, such programs often come with a hefty price tag, with fully funded options few and far between.

But regardless of whether you go for an MFA, some things are critical to establishing a career as an author that you probably don’t know, unless you’ve learned them the hard way (or you’ve worked in publishing).

I say this as someone who went for an MFA and then went on to establish a career as both an author and an editor. And this is information I want to circulate widely—first, because I know how hard it is to have all the education in the world and still feel like you have no idea what you’re doing, and second, because until you really know what you’re dealing with in this industry, it’s easy to find yourself paralyzed by self-doubt, second guessing yourself and your work ad infinitum.

Writing takes grit, and so does publishing. Both are easier if you understand what you’re up against. Here are three publishing “secrets” I think everyone should know.

1. Agents and acquisitions editors don’t read the same way peers and mentors do.

When you’ve written a full-length manuscript, it’s nearly impossible to read it the way a stranger will (as Margaret Atwood put it, you already know “where the rabbits are hidden”). Which is why so many experts emphasize the importance of mentors and critique groups.

But mentors are often focused on teaching the principles behind good creative writing, and helping the author develop their skills overall, rather than on what it will actually take to get a given manuscript over the finish line. Like members of a critique group, mentors also tend to look at the manuscript a piece at a time, rather than as a whole, which inevitably results in more feedback on the manuscript’s details than on its overall structure.

Also: both mentors and critique group partners tend to have a certain amount of patience for work that “isn’t quite there yet,” in a way that can obscure the issues that will keep it from getting published.

Agents and editors have two modes when they read. The first is the mode applied to the opening of a manuscript, where they’re reading quickly but closely, alert for the sort of prose that signals a unique voice, control of the language, and stakes in the story, along with the sense that they’re “in good hands” with this storyteller. Everything else, the publishing pro will happily delete from their inbox.

The second mode is also quick, but not nearly as close—in this mode, the agent or editor is often skimming for story as a whole, looking at the way the characters develop, the way one thing leads to the next, and how the story adheres emotionally. If any of these elements are missing, misplaced, or murky, no matter how good the writing is, the pro is likely to pass.

This is why, when I work with aspiring authors, we zero in on their book’s opening pages, with a focus on clarity, concision, and word choice. I also encourage them to think critically about where that book opens, what kind of picture the opening creates in the reader’s mind, sentence by sentence, and how to front load the book’s key themes with those first few pages. (Peter Selgin has a great series on this topic here on Jane’s blog, which I encourage everyone to check out.)

This is also why I emphasize the key big-picture issues in long-form storytelling: character arc (and the internal reflection that reveals it), causality and consequence, questions and tensions (the fuel that feeds narrative momentum), and pacing.

You’ll never be able to forget where your rabbits are hidden, but teaching yourself to read your own work in these two modes will change the way you see it, guaranteed—and, ultimately, improve your odds when you send it out.

2. It’s a numbers game.

Much has been said on the subject of grit as a writer, and beyond the fortitude it takes to actually write a book, publishing is where that quality really comes in. There are two main factors here, beyond the quality of your work: the first is how many submissions you’re sending out, and the second is where you’re sending them.

When I work with authors, I emphasize the importance of establishing a submissions practice as well as a writing practice. Just like writing, the process of submitting should feel regular and routine, rather than something that only happens when you’re inspired. A good way to accomplish this is to build your submissions practice around your existing rhythms and routines—for example, by dedicating a portion of your writing time each week to submissions, or by creating a spreadsheet that takes the guesswork out of where to submit next when you (inevitably) receive a rejection.

That’s the “how many” part of the submissions process. As far as the “where to,” you can increase your odds of acceptance by being smart about where (and how) you submit. For instance, submitting earlier in the open period for a journal or anthology is often a good idea; if the journal is run by staff, as opposed to students, those staff members probably won’t wait until the deadline has passed to get started in on the slush pile, and, as with anthologies, the first story submitted on a given subject or theme has better odds of being selected than the second. Also, look for submissions opportunities with clear constraints, as only being open to submissions for a week or two, or exclusively to contributors hailing from one geographic region or demographic, can cut down on the competition considerably.

All of us start off wanting to be the exception, the one who didn’t have to try all that hard to get published. But if a half-hearted submissions game hasn’t yet gotten you where you want to be, it’s time to get serious, and strategic.

3. “Comps” aren’t just for the marketing department.

Agents and editors always want to know about “comps,” or comparable/competitive titles for the books they represent, acquire and market, but this tends to be something the writer puts off thinking about until they’re trying to write a query letter for their manuscript. This leads to freaking out, because not only do they have no idea what a comparable title might be, they have no idea how to talk about their book in a way that will make sense to other human beings.

I encourage my clients and students to start thinking about “comps” early on. Well-known and much-loved books in your field or genre can act as touchstones, offering some useful shorthand for complexities that can be hard to describe; as such, the back-cover copy of comp titles can be hugely helpful in figuring out how to talk about your book, and then, when the time comes, pitch it.

The back-cover copy of such titles reflects the way books like yours are sold; slanting your pitch so that it’s clearly in conversation with that sort of copy reflects a level of savvy that publishing pros tend to appreciate, because it’s frankly pretty rare. (Many newer writers either don’t bother to read within their own genre or think their book is so exceptional that they have to reinvent the wheel in order to explain it, which is rarely the case.)

“Comps” can also be useful in terms of authors whose work is similar to your own. For instance: Love Kelly Link? Do you, like her, write short stories that blur the lines between literary and speculative? Open up Link’s first collection, Get in Trouble, and look at where the stories in it were first published. These are publications open to work that blurs those bounds; they can help you set the stage for a successful career with this sort of short fiction.

On the other hand, maybe you’re the sort of writer who’s all over the place: you’re working on a family saga, and you’ve got some short fantasy in a drawer, but really, your most marketable project may be that historical novel you abandoned a few years back. In that case, the publication history of the author Karen Joy Fowler may be a good model for you, both in terms of where to submit your shorter work and which book to debut with.

If you haven’t worked hard to hone your craft, none of these strategies will nab you a book deal or major byline. But if you have, they can—and if applied diligently, they will.

Many readers here are accomplished authors themselves, and I know many of you share my passion for helping writers. So now it’s your turn: What, in your opinion, is one critical thing “no one ever tells you” about publishing?

Note from Jane: Susan’s new class, Fiction: Final Draft, was developed for writers who’ve put in their 10,000 hours but have yet to break through with their first book deal. Participants will learn how to win the battle of publication at the level of the line, with tips and tricks from the editor’s toolbox, as well as storytelling principles derived from neuroscience, information theory, and more. Called by one participant “a finishing school for writers distilled into just four weeks,” Final Draft begins September 24; more information here.

September 13, 2019

The People in Publishing I Learn From

Jane at Digital Book World 2019

At Digital Book World this past week, I was honored to receive the Publishing Commentator of the Year Award. And when I accepted the award, I shared the following fun anecdote.

In 2009, when I was still working for F+W Media, the executive team came back from the O’Reilly Tools of Change (TOC) conference and expressed a desire to launch a competing event. At the time, TOC was the most forward-thinking event in the book publishing industry—incredibly well regarded—while F+W was a Midwestern publisher—not incredibly well recognized—inside the publishing industry. I more or less considered the idea crazy and thought the whole idea would implode before it could achieve liftoff.

I was wrong. To add to my consternation, once the event had a real date, it was put into my budget line. The executives reached out to Mike Shatzkin to program the event (a brilliant move I did recognize), and said I should start advising him on planning and programming. That was pretty silly, of course—it was Shatzkin who would be advising me.

Long story short, it’s been a strange and unexpected road from then to now, to be recognized at an event I discouraged from existing in the first place. One thing that hasn’t changed in ten years, though, is how much I learn from others in the publishing industry. Understanding the business is a continual work in progress, so here are some of the people who’ve taught me so much in their own commentary.

Longtime Industry Veterans

Victoria Strauss

Through her work at Writer Beware, Victoria is one of the most visible authorities in the author community, keeping us all informed about predatory companies and practices. At Writer’s Digest, she was a resource for editors to call on to vet publishers and services. She may be the most eminently fair and measured voice out there, someone whose opinion I seek out when I have questions about publishers or services I don’t recognize.

Bo Sacks

During my earliest days at Writer’s Digest, when I worked on the magazine, my boss told me to subscribe to the Bo Sacks newsletter. I did and haven’t stopped in the 20 years since. I credit Bo for eliminating any nostalgic, protective attitude I might have had toward my own industry—to accept the necessity of transformation and how we each can adapt, while retaining the values that brought us to the industry in the first place.

Michael Cader

Michael Cader founded and writes a good portion of Publishers Lunch, the weekday email every agent and editor reads. That’s about all one needs to know. My own newsletter, The Hot Sheet, is shamelessly and directly inspired by his work.

Mike Shatzkin

As I indicated in my prefacing story, Mike is a leading publishing industry expert, someone I discovered through his industry talks that I first read online. (He posted the written versions.) In the mid-2000s, he was the only one I could find—perhaps because I was not in NYC—who was speaking the truth about where the publishing industry was headed. His commentary at his blog remains among the most incisive and on target—he has a rich history and deep network.

Kristine Kathryn Rusch

While there are some other authors on this list, there is none like Kristine Kathryn Rusch, who has published an enormous volume of work over many years, both traditionally and independently. She writes a series at her blog, Business Musings, that discusses trends and changes in the industry. Her commentary reflects the business-oriented and proactive attitude that’s emblematic of the best of today’s independent authors.

Authors and Colleagues

Orna Ross

I first met Orna via email around 2012, when she was building a team of advisers for a new organization, the Alliance of Independent Authors. Knowing how hard it is to build a new brand and organization from scratch, I had my doubts about whether it would have legs—but that was a sore underestimation of Orna (and her husband, who is co-director). ALLi is now one of the most important organizations for authors, doing advocacy work alongside education, and she’s behind industry programming for authors at London Book Fair, among other venues.

Pete McCarthy

Pete is a former Big Five marketing VP whose writings and talks I started following after I saw him referenced by Mike Shatzkin. He presented something I didn’t see anywhere else: data-driven marketing strategies and tools—approaches that are clearly the future in an era of online retail, search optimization, and social media. Never miss his talks if you see him on a conference schedule, or follow him on Twitter.

Anne Trubek

Anne’s email newsletter, Notes From a Small Press, is full of insights each week about what it takes to run a sustainable (profitable) book publishing operation. Anne keeps it real, and the topics she covers are as relevant to authors as to small, independent publishers.

Guy Gonzalez

Guy and I worked together briefly at Writer’s Digest and Digital Book World, during which time I got a super-charged education in marketing for the digital age. He turned me onto The Cluetrain Manifesto, which holds up many years later as a set of core values for any business trying to succeed, especially in online environments. Guy has strong opinions on what’s happening in publishing, for which I’m grateful. Follow him on Twitter.

Margot Atwell

This is the newest person on this list—in terms of when I encountered them. I first heard Margot present at London Book Fair on the future of publishing. She’s since hosted an online conference on the same topic—and has a newsletter with regular insights about money and publishing. She works as head of publishing at Kickstarter.

And Others

I subscribe to a range of indispensable newsletters, blogs, podcasts, and social feeds, including those from Joanna Penn, Market Partners International, Thad McIlroy, David Moldawer, Kate McKean, Amy Collins, Sam Missingham, Mark Williams, David Gaughran—and more I know I’m forgetting!

As I mentioned on Twitter, the funny thing about being any good as a publishing commentator: it requires talking to many others, learning varied perspectives, and writing about ideas you didn’t come up with. I’m deeply indebted to the community and hope to keep serving in the years ahead.

Whose publishing commentary do you follow? Let us all know in the comments.

Jane Friedman

- Jane Friedman's profile

- 1882 followers