Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 87

November 27, 2019

A Vivid Character Is More Than a Series of Attributes

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress.

First Page

When Lucia and I met in the mid-1960s, we were thoughtful, idealistic young women. Knowing her really began after she realized what those around her always knew—that she was not crazy but a true individual, an independent thinker with an incredible imagination.

Her affinity for names began almost at birth when her parents were told before her Baptismal that the name they had chosen was not a saint’s and would have to be changed. Her parents kept the name they originally selected and added two saint’s names. Her identity was forged with two first names, two middle names and a surname. Her mother contributed the nickname, Boobie, which she kept along with the many names she gave herself. She acquired the name Lucia as part of the Italian persona she assumed after several visits to Italy and a lifelong obsession with the Italian Renaissance.

Lucia understood from early childhood that she possessed characteristics that made her different from others—an only child, left-handed, born under the zodiac sign of Capricorn in the Chinese year of the Water Horse. Quite a combination of attributes and not easily understood. Few people are confronted with queries about what defines them, and even fewer ask themselves. It becomes one of those mystery-of-life conundrums that when pondered reveal interesting truths—if answered honestly or at all. Lucia considered all aspects of her personality a means of gaining self-awareness. Left-handed people are visual thinkers, and Lucia epitomized this mindset.

“Nothing analytical, thank you very much.”

“What about math?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“Repetitive tasks?”

Again, not for Lucia, who was unlikely to engage in something that when considered, if she took the time to do so, was to her way of thinking so mind-numbingly dull. To delight her, one need only provide something to quicken the pulse and stir the heart, something to make her laugh and cry—simultaneously if possible. For her, Renaissance art, Barber’s Adagio for Strings or watching Baryshnikov dance filled the bill.

First-Page Critique

The very well-written first page of this novel-in-progress presents us with a female protagonist, a woman of extraordinary virtues and eccentricities. Or so we are told by the first-person narrator.

According to the narrator, Lucia

— is “a true individual.”

— is “an independent thinker.”

— has “an incredible imagination.”

We learn furthermore that Lucia is a woman of many names—including the saintly names given to her at birth by her parents, and nicknames assigned to her later by herself and others, Lucia being just one of many (presumably the one by which the narrator knows her).

But Lucia’s abundance of names accounts for only one of many eccentricities, which include her being an only child, left-handed, and a Capricorn “in the Chinese year of the Water Horse.” All this we’re told by the narrator, who goes on to tell us that these and other characteristics “made [Lucia] different from others.”

One method of evoking characters is by way of other characters—in this case, by way of a first-person narrator who, at least for the time being, remains unnamed, and, for the most part, anonymous. With respect to the narrator, we can with certainty say only that she is a woman, that she came of age in the 1960s and is probably a woman in her sixties. We can also assume that she admires Lucia; anyway, she couches her opinions in terms of admiration (so does Marc Antony when speaking of Caesar to the mob).

There are two potential problems with this method of character evocation. The first is that it leaves room for doubt. First person narrators are human, and unless they are of a particularly objective bent, humans tend to look at the world through subjective eyes. Therefore first-person human narrators are seldom completely objective; which is to say that no character narrator is one-hundred percent reliable.

Instead, what we typically get from first person narrators (as opposed to omniscient or third-person narrators) is, to some extent, an opinion. It’s up to us readers to decide how much to invest in those opinions, what degree of credibility to assign to them.

And the degree of credibility assigned to a first-person narrator is based largely on the extent to which the narrator’s opinions are supported by evidence. The more concrete the evidence, the stronger. When, for instance, the butler narrator of Ishiguro’s Remains of the Day tells us that, in forsaking his love for Miss Kenton he was acting appropriately given his vocation, we see right through this rationalization into the narrator’s broken heart. Similarly, when at the start of John Cheever’s short story “Goodbye, My Brother” the narrator tells us, “We are a family that has always been very close in spirit,” we do well to greet this claim with—if not utter skepticism, something short of complete trust—since by the end of the story the same narrator will have clobbered his brother with a large tree root and it will be all too clear that the only “spirit” binding this family is gin (with a touch of vermouth).

Here, with this first page, since we’re presented almost exclusively with abstractions (“thoughtful,” “idealistic,” “independent,” “incredible,” “different”), with no concrete evidence in the form of scenes or tactile examples to illustrate and lend support to them, at the end of this first page we’re left with only a fuzzy sense of both the narrator and her subject. Neither character leaps off the page, and both remain largely abstract.

Which brings us to the second problem with the approach used here. It relies too thoroughly on abstractions. “Show, don’t tell,” goes the creative writing teacher’s chestnut. And though it’s not terrible advice, still, there’s nothing wrong, intrinsically, with telling, just as there’s nothing wrong per se with abstractions. But unless they’re backed up with solid evidence in the form of actions or images, abstractions alone aren’t very satisfying.

Here, to the extent that Lucia is evoked at all, she is evoked through a series of abstract opinions. On the continuum of evidence, opinions rank pretty low, down there with rumor, gossip, and innuendo. As with rumors, we reserve judgment on them until they are either proven or refuted.

Until I have more evidence, I’ll do likewise with Lucia.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

Note: The publisher of Your First Page is offering free shipping if you order the book directly from their site. Use code YFPfreeship.

November 21, 2019

6 Steps to Get Your Self-Published Book Into Libraries

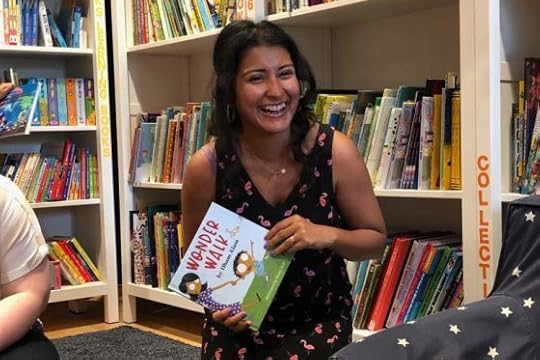

Today’s post is by debut children’s author Ilham Alam (@IlhamAl50397575), whose rhyming picture book, Wonder Walk, is available now.

I’ve long dreamed of getting my book into the public libraries at home, in Canada. But because I published with a hybrid press for my debut children’s picture book, I had to do the work of getting the book into libraries myself.

With trial and error, I’ve identified six steps that have helped my book enter library circulation, even though I did not have the might of a traditional publisher’s marketing team, agent, or PR team.

While this worked for library systems in Ontario, Canada, the same steps should work for any local library system. I’m also sharing the template I used to approach libraries.

1. Research, research, research.

Look at the public library’s website to find out whether they have a system for accepting self-published books into circulation. Or you can contact the head librarian or the procurement librarian for the specific department that corresponds to your book genre. For example, I always looked for the head children’s librarian of the system that I was reaching out to.

2. Nice people finish first.

Whether you approach via phone, email or in-person, always remember to be polite and approachable. When you find out the name of the relevant person to contact, address them personally and show you care.

3. Create a sell sheet.

Prepare a basic sell sheet including your book’s cover, title, the publisher, available formats and ISBNs, pricing, a brief description of the book, why it will appeal to library patrons, significant blurbs or awards, and how it can be ordered. This information can be incorporated into an email, or it can be designed and printed as a one-page shell sheet that you can take with you if meeting librarians in person.

4. Show off (persuade) a little.

If you pitch the library via email, definitely include links to your profile on your publisher’s website (if there is one), your own author website or blog, and your social media channels.

For easy reference, on a single page of your website, compile your review links, pictures of your book’s cover, social media links, and photos of any author events you’ve done. Then link to this in your pitch email.

In your pitch, mention other libraries that have already bought your book, if any, as that helps validate the quality and desirability of your book.

5. Ensure your book is available from library wholesalers.

This makes the difference between your book getting accepted or rejected. And I found this out the hard way! Ensure that your book is available through Baker & Taylor (US and Canada), WhiteHots (Canada) and Library Services Center (Canada). Libraries can then easily find your book and buy it from these wholesalers.

6. Offer to do an event.

Let libraries know that you are happy to come in and do author readings and book signings. It’s a win-win: you get more exposure and the library gets to have programming for their community members. This is especially helpful for smaller libraries.

To do this, however, you must do your part to promote your appearances, as you want to ensure there is good attendance at your author reading.

Librarian pitch template

Hello [Name of Librarian],

I hope that this email finds you well. I’m a Canadian author of children’s books from nearby Toronto. My debut picture book, Wonder Walk, has been released by Iguana Books and is available through library distributors such as Library Services Centre, WhiteHots and Baker & Taylor.

Written in rhyming verse, Wonder Walk is perfect for pre-schoolers and celebrates the parent-child relationship, when the insatiably curious Johnny asks his mom endless questions about the cuddly cuddle-bug and the curt red bird, and all the other natural wonders that he sees.

Beagles and Books wrote, “With big, bold illustrations and concise, rhyming text, Wonder Walk is a story that young children will enjoy and may prompt families to take their own walk together to observe nature and ask questions.”

Libraries in the Durham region such as in Whitby and Clarington have added Wonder Walk to their children’s collections. I was hoping that Blue Mountain Public Libraries would be interested in adding Wonder Walk to their collections as well.

Here’s more information about Wonder Walk at Iguana Books:

[web address]

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1771803236 ($25.99)

Paperback ISBN: 978-1771803076 ($9.99)

Moreover, here is a link to my author website, Story Mummy, which includes more reviews for Wonder Walk:

[web address]

Thank you, and I look forward to hearing back from you.

For more insight

Getting Self-Published Books Into Libraries

Public Libraries: How Author Can Increase Both Discoverability and Earnings

November 20, 2019

When Your Story Opening Does Nothing But Blow Smoke

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress.

First Page

It was midnight when I sat down to write my masterpiece. I would include everything and nothing. In so doing, I would transform my personality, distilling it into some immortal work of art, created by me, for me. I would be the vatic chronicler of my own mind-windings, the perambulations of a brain seeking egress from banality. Either it (my personality) would flower, bloom and expand like some kaleidoscopic balloon, or it would vanish entirely from the earth, allowing whatever creativity was trapped inside my brain to surge forth unchecked like a rabid river. Either way, I would sooner or later have on my hands something worthwhile, a collection of letters, words and phrases that meant something, meant something powerful, did justice to all my dreams, longings and hopes.

Of course, I didn’t really believe in anything that was immortal. Nor did I think that anything I wrote would somehow supply me with a final, terminal quenching of my desire. But a part of me wanted to believe in such a possibility, the same part of me that wanted to believe in God, even though I knew it was only a morbid consolation. I wanted to believe in these myths, while at the same time I was skeptical of them.

But, either way, I poised my pen above the paper. I was prepared to strike, to draw fresh blood, to finally write the masterpiece whose possibility and potential gnawed at the gnarled roots of my soul, even while I mocked the hope and set it on a realistic table to see its worried corners and haunted dents. My experience, I said to myself, in all its mortifying banality, would serve me now. How, I wasn’t so sure. But it seemed to me that experience was like a landscape; that the sun shone on it and the moon flowed down it like anything else, and it was up to me to capture those moments when something interesting happened, when the flowers bloomed or the tulips cracked.

So then and there, I wrote down the first words, the unremarkable, terrible words. These words were profoundly un-sublime. They were mired in the juice of the mundane, fairly squeaking with a lack of originality. I will not repeat them here, but suffice it to say they were mawkish and uninspired, which I found confusing, for the fit that produced them seemed to me then to be very inspired, somehow forceful and effervescent.

First-Page Critique

Older readers may remember The Honeymooners, and Ed Norton, Ralph Kramden (Jackie Gleason)’s sidekick, the vest-and-tee-shirt wearing municipal sewer employee played to a fare-thee-well by Art Carney. In one of his better schticks, Norton would confront some trivial task with extravagant overtures, loosening his shoulders, licking his lips, rubbing his hands and rolling his sleeves (or their equivalent, Norton being sleeveless), approaching the task like a pool player trying for a three-ball shot the hard way, until finally an exasperated Ralph Kramden bellowed, “Will you cut that out!”

Reading this impressively written, ornately empty opening, I feel like Ralph Kramden, or like Dorothy confronting the man she believes is The Wizard of Oz, when in fact she’s witnessing a fraud operated by a humbug. In The Wizard of Oz the sham is achieved with smoke, flames, a thunderous basso profundo, and 1939’s cinematic equivalent of a hologram. In this first page the smokescreen is achieved through language as oozing and pungent as an overripe Camembert (“gnawed at the gnarled roots of my soul,” “a landscape that the sun shined on”), language designed as much to camouflage a lack of content as to convey it. The purple prose is amusing (“[My words] were mired in the juice of the mundane, fairly squeaking with a lack of originality”). The narrator is blowing smoke, but it’s witty, colorful smoke.

I’m reminded of another smoke-blowing opener:

“Listen to me. I will tell you the truth about a man’s life. I will tell you the truth about his love for women. That he never hates them. Already you think I’m on the wrong track. Stay with me. Really—I’m a master of magic.

“Do you believe a man can truly love a woman and constantly betray her? Never mind physically, but betray her in his mind, in the very ‘poetry of his soul.’ Well, it’s not easy, but men do it all the time.

“Do you want to know how women can love you, feed you that love deliberately to poison your body and mind simply to destroy you? And out of passionate love choose not to love you anymore? And at the same time dizzy you with an idiot’s ecstasy? Impossible? That’s the easy part.

“But don’t run away. This is not a love story.

“I will make you feel the painful beauty of a child, the animal horniness of the adolescent male, the yearning suicidal moodiness of the young female. And then (here’s the hard part) show you how time turns man and woman around full circle, exchanged in body and soul.

“And then of course there is TRUE LOVE. Don’t go away! It exists or I will make it exist. I’m not a master of magic for nothing. Is it worth what it cost? And how about sexual fidelity? Does it work? Is it love? Is it even human, that perverse passion to be with only one person? And if it doesn’t work, do you still get a bonus for trying? Can it work both ways? Of course not, that’s easy. And yet—”…

The more this narrator of Mario Puzo’s Fools Die exhorts this reader to “stay with [him],” to not “run away,” the more inclined I am to head for the hills. That the author’s previous novel was the mega-bestselling The Godfather changes nothing for me. For me this first page is all foam and no beer, less amusingly so than the first page that precedes it. Meant to pull me in, Puzo’s hard sell puts me off.

Puzo is hardly the first novelist to roll his sleeves up in public. Somerset Maugham begins The Razor’s Edge (1944), his most ambitious novel, thus:

I have never begun a novel with more misgiving. If I call it a novel it is only because I don’t know what else to call it. I have little story to tell and I end neither with a death nor a marriage. Death ends all things and so is the comprehensive conclusion of a story, but marriage finishes it very properly too and the sophisticated are ill-advised to sneer at what is by convention termed a happy ending. It is a sound instinct of the common people which persuades them that with this all that needs to be said is said. When male and female, after whatever vicissitudes you like, are at last brought together they have fulfilled their biological function and interest passes to the generation that is to come. But I leave my reader in the air. This book consists of my recollections of a man with whom I was thrown into close contact only at long intervals, and I have little knowledge of what happened to him in between. I suppose that by the exercise of invention I could fill the gaps plausibly enough and so make my narrative more coherent; but I have no wish to do that. I only want to set down what I know of my own knowledge.

Maugham spends four more long paragraphs—all of Chapter One—rolling up his sleeves, clearing his throat, parsing his apprehensions with respect to writing the novel we are about to read, before getting down to brass tacks with Chapter Two. Could the first chapter of The Razor’s Edge be cut without harming vital plot tissue? Yes, if plot is all that counts. But with his first chapter Maugham is up to something else. He’s gaining a sense of authority through making himself human and vulnerable, swirling brandy in a padded chair in his fire-lit parlor: the author cozying up to the reader, earning the reader’s trust (that he happens to be Somerset Maugham doesn’t hurt).

Another kind of intimacy is established within the first sleeve-rolling paragraphs of Michael Faber’s 2002 historical novel, The Crimson Petal and the White. It begins:

Watch your step. Keep your wits about you; you will need them. This city I am bringing you to is vast and intricate, and you have not been here before. You may imagine, from other stories you’ve read, that you know it well, but those stories flattered you, welcoming you as a friend, treating you as if you belonged. The truth is that you are an alien from another time and place altogether.

It takes Faber’s narrator six more paragraphs—as long as Maugham—to bring us to an event, or rather to a place, Church Lane, “the sort of street where even the cats are thin and hollow-eyed for want of meat, the sort of street where men who profess to be labourers never seem to labour and so-called washer-women rarely wash.” From this seamy street we are escorted through the back door of a squalid rooming house, down a “claustrophobic corridor” reeking “of slowly percolating carpet and soiled linen,” up a flight of rotten stairs to a room in which a prostitute squats over a large ceramic bowl.

Unlike Maugham’s cozy first paragraphs, Faber’s achieve a tense intimacy between reader and narrator, such that, however reluctantly, the latter is compelled to follow the former into the most repugnant venues of Victorian London society. As the reviewer for The Guardian noted, “Playing on the omniscience of the … narrator, Faber leads us through his labyrinthine story in the come-hither voice of a brothel madam, breaching the boundaries of voyeurism within the first few pages by bidding us to slide into bed beside a prostitute.” Before doing so, however, first Faber gets the reader into bed with his narrator.

While the opening to Maugham’s novel plants the seeds of his story, and Faber’s delivers us into a prostitute’s boudoir while immersing us in its seamy Victorian London setting, beyond the anti-climax delivered by its last paragraph it’s hard for me to see what story our first page may be setting up for us. Perhaps that’s why, despite the amusingly overripe diction, it feels empty. It would help to be given some clue as to what is at stake for the narrator as he (let’s assume he’s a man) prepares to pen his “masterpiece.” What if he can’t write it? Obviously it matters to him. But what would make it matter to us? Instead we get three long paragraphs of the narrator telling us he wants (for no particular reason) to write a masterpiece, followed by a short one wherein he fails to do so. If there’s a potential story in there somewhere about the extremes to which one man will go to achieve literary fortune and fame, how those extremes are met and the consequences that arise from them, it’s been left out of the sandwich, leaving us with two slices of bread, a lettuce leaf, and some mustard. Empty calories. Sleeve-rolling, and not much more.

A final famous bit of sleeve-rolling:

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll probably want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.

Having acquainted us with his miserable attitude, from there Holden Caulfield dives straight into his story “about this madman stuff that happened to [him] around last Christmas …”. A good rule-of-thumb regarding sleeve-rolling: a little goes a long way.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

Note: The publisher of Your First Page is offering free shipping if you order the book directly from their site. Use code YFPfreeship.

November 14, 2019

How and Why to Build a Twitter Following While Unpublished

Today’s guest post is by author Emma Lombard (@LombardEmma).

As a new author, there is so much conflicting information about whether you should or shouldn’t have an author platform before you’re published. I decided to err on the side of caution, and forge ahead with building one, starting with resurrecting my dormant Twitter account. I pretty much started from scratch with only 36 followers and very little knowledge about how Twitter worked.

Through a crazy baptism of fire, I soon learned the ins and outs of Twitter. I jotted down my discoveries in a blog series called Twitter Tips for Newbies, which, to my utter surprise, has proven popular in Twitter’s #WritingCommunity.

So far, I’ve amassed 20,000 followers on Twitter in my first year. Before I dig into how that happened, a couple quick ground rules if you’re new to the Twitter community:

Don’t follow without screening who you are following first—or you’ll end up with some eye-popping content on your feed).

Keep your follower-following numbers even while you’re below the 5,000 mark. Don’t race ahead and follow a bazillion accounts. Essentially, this is what bots do and Twitter will put you in Twitter jail and prevent you from following accounts.

Here are my top three call-to-action strategies that work.

1. Retweeting = Exposure

Once a week, I post a tweet offering to retweet my follower’s pinned posts. When you offer this first, it makes it easier to then ask them to retweet yours too (as opposed to just yelling out into the Twitter void that you want your pinned post retweeted). But I always go one step further and ask them to also support and retweet 5 other pinned posts from folks on that thread.

The upside to this:

Folks online love this rallying of the troops. Yes, it may mean I end up retweeting hundreds of pinned tweets over a few days, but the payoff is having hundreds of folks retweet my pinned post. It’s a win-win for everyone.

Twitter’s algorithms perk up and pay attention to a post that is getting a lot of activity and will push your pinned post out for more people to see—so make sure your pinned post is worthy of sharing far and wide.

The downside to this:

I’ve read so many people (including those who comment on my retweet feeds) that they won’t even retweet all 5 pinned posts in one day because they don’t want to fill their Twitter feed with retweets and scare off their followers. But Twitter’s algorithms do not push every single retweet onto people’s feeds, so you won’t be flooding their feeds with dozens of retweets (plus, Twitter has an option to turn off follower’s retweets if you find them annoying).

If you don’t support your followers, later on, no one is going to step up and help you. You’ll be surprised who remembers.

My biggest wins using this strategy:

This is how my Twitter Tips for Newbies blog series exploded onto the #WritingCommunity scene.

It’s also how, in less than two months, I gathered over 100 subscribers to my brand-new newsletter, By the Book.

2. Promote Newbies

I regularly post a tweet dedicated to writers and readers with fewer than 1,000 followers. I give newbies a larger platform on which to meet other newbies. Some folks are terribly intimidated by large accounts, but they quite happily engage with smaller accounts. This is why I rally my other followers with more than 1,000 followers to retweet the post.

The upside to this:

Until newbies have at least 1,000 followers, they aren’t even a blip on Twitter’s algorithm radar. Even if they have a couple hundred followers, the algorithms don’t push them onto their followers’ feed. So, helping newbies get over this 1,000-follower mark is doing them a great service.

When you’ve helped someone in their often terrifying first few days or weeks on Twitter, they don’t forget you! It’s one sure-fire way to build up champions in your corner.

The downside to this:

Sometimes you might follow a new account that doesn’t have any history, so you don’t know if they’re a good fit for you. If you take a punt on a newbie and suddenly discover a few days later that they are pushing out content that makes you uncomfortable, it’s okay to unfollow them (though don’t just unfollow for the sake of building up your numbers—many folks have a nose for this and will call you out on it).

My biggest wins using this strategy:

I fell in love with literary agent Janet Reid’s Query Shark blog, where she critiques query letters online. So, imagine how hard I fan-girled the day Janet followed me on Twitter and then sent me a message thanking me for helping one of her authors build their Twitter platform! I nearly fell off my chair. It just goes to show, you never know who’s watching.

While I was still numb with shock, I made one of the most audacious moves of my career at that stage and I emailed Janet asking her if she’d grant me an interview with her. She said YES because by that stage I’d helped another two of her authors with their Twitter platforms. I was oblivious to these connections. This time, the chair could not hold me and I happy danced around my kitchen much to the disdain of my two cats.

This then opened the door for me to use Janet’s query letter critique service for my own query letter, which has so far helped me hook two agents into reading my manuscript.

3. Engage, Engage, Engage

Lift other writers up and celebrate their achievements—they aren’t your competition, they are your peers and team mates. Share what you’ve discovered on your authoring journey, including your blunders (readers love seeing your vulnerabilities; it helps build real connections with people).

More ideas for engagement: Welcome newbies. If someone’s having a bad day, send them a gif hug. Enter competitions and giveaways. Respond to the comments on your tweets. Post and comment on interesting articles.

And have fun.

The upside to this:

You never know who just might pop out of the woodwork and end up following you.

Even if folks in the publishing industry are not following you, you can be sure that they’ll be noticing your online behavior and activity. If you’re playing the long game of becoming a professional writer, this kind of attention is invaluable.

The downside to this:

If you choose to be more liberal with your voice online, this may be a deterrent to some followers.

On the other hand, it may also attract you to others who are more your tribe, though this may shrink your networking opportunities.

My biggest wins using this strategy:

By using the #HistoricalFiction hashtag, I was followed by historical fiction specialist editor, Andrew Noakes from The History Quill at the exact moment in my career when I needed an editor! Not only have Andrew and his team proven to be consummate professionals in helping me edit my manuscript, but I was also drawn into his writing workshop and critique group. I now have several published historical fiction authors as critique partners, who provide exceptional feedback on my latest work.

Twitter is where I found my amazingly talented illustrator, Tara Phillips. And where I won a competition to have one of my characters illustrated by author and illustrator Eleonora Mignoli.

I’m now invited to write guest blogs on other websites, and I have successfully secured interviews with other publishing industry professionals and writers. (Don’t be shy to ask—you’ll be surprised how many people are amenable to doing an interview or being a guest blogger. The worst that can happen is they say no.)

I’ve been invited to write for and compile two separate anthologies (that I’ve unfortunately had to turn down due to not wanting to overburden myself).

Still Not Published

All this has happened in a year and I still don’t have my novel published—it’s currently in the querying trenches.

I don’t want this to sound like a brag fest—I want to show other new writers out there that there is great value in using Twitter as part of your author platform. Overall, the key to a successful Twitter account is engagement. Engage with and lift up other writers and readers so that when your day comes to share news about your book launch, you will have champions in your corner.

November 13, 2019

Exposition Should Serve the Scene, Not the Other Way Around

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Submit your first page for critique.

First Page

Easter sat on the clifftop looking out over the bright sea. There was a steady onshore breeze blowing, stinging her eyes and tossing her hair out behind her. She refused to bind her hair, as her mother bid her do, for the eyes of the young men followed the hair as it bounced and swayed and danced. The eyes of the young men were a novelty and a delight. Not so long ago a child’s smock had hung from narrow shoulders straight downward to the ground. But now a woman’s dress flowed over curves like the tide flowing over smooth stones. The eyes of the young men followed the curves. They hung around her like seagulls hanging on the wind, eyes hungry for something beneath the surface of the wave.

Nor was she shy about looking at the young men. In the autumn, when the harvest had called every able body, man, woman, child, noble, free, and slave, into the fields from dawn till dusk, she had gloried in their broad backs, the flow of their muscles under the skin, the salt sweat of their tanned faces. And in the quiet of the evenings, she had found herself delighting in the thought of lying beside this one or that in the soft new-cut grass, and of the rasp of a calloused hand upon soft flesh.

She was not for them, of course. She was a thegn’s daughter, and promised long since to an ealdorman’s son. Their eyes had no right to follow as they did. Her thoughts had no right to stray to hard hands or soft grass.

She was herself the product of a harvest tryst, as she had learned the year before, when her mother, Edith, a little wistful and a little tipsy, in the glow of a winter fire, had told how the daughter of a Welisc slave had become the wife of an Anglish thegn. Her mother’s tale had, for a while, made a pile of straw beneath of dome of stars seem a richer bed than any hall or villa could provide. But the tale had ended with a moral. Had her father not chosen to take her mother to wife, he had only to place a few shillings in a freeman’s pocket to marry Edith and raise the thegn’s child as his own. That would have settled that matter, and Edith would have lost nothing. But there was no such option for a thegn’s daughter, particularly one who had been promised from birth to the son of a greater lord. From where she sat, she could only fall. And so Easter had not lain in straw beneath the stars, not tasted salt sweat or a warm mouth, not felt hard hands gentle on her softness. She had lain, as she always did, at home in the hall in the bed she shared with her sisters.

First-Page Critique

In Glengarry Glen Ross, David Mamet’s drama about a group of desperate real estate salesmen, there’s a scene in which an aggressive head-honcho from headquarters (Alex Baldwin in the movie version) arrives to remind them of the most important imperative of real estate sales, the “ABC rule”: “Always Be Closing.”

I share a similar injunction with my writing students: Always be writing scene, with the understanding that a scene includes not just the basic elements of drama—action, dialogue, and setting—but descriptions, exposition, flashbacks, and any other contextual matter that helps us to understand and appreciate the scene in question. If “show, don’t tell” isn’t always good advice, it’s because it ignores the fact that more often than not telling and showing go hand in hand. They need each other.

Sometimes, though, showing may be at odds with telling, and vice-versa, as on this first page, one that—however beautifully written—raises the question: When is a scene really a scene, and when is it just an expedient for exposition?

The scene: a woman (“Easter”) sits at the top of a cliff overlooking the sea, the wind tossing her hair behind her. The exposition occasioned by the scene: how for years Easter’s hair has been an object of fascination among the local “young men,” and how, as she has matured, to the presumed consternation of her mother who consistently “bid her” to wear it bound, she has become an object of sexual intrigue and conjecture.

The image of Easter sitting on that wind-swept cliff in her “woman’s dress [that flows] over [her] curves like the tide flowing over smooth stones” is powerfully evoked and no less alluring than her hair to those young men. But no sooner is it evoked than we leave her sitting there on that cliff to be taken to a vague location where “[t]he eyes of the young men [follow those] curves.” Or are the young men actually watching her from a distance as she sits on that cliff, as suggested by their eyes being likened to the seagulls “hanging on the wind”? Though it’s possible, I doubt it. To me the scene finds the protagonist distinctly alone, out of sight of those probing eyes.

Which raises the question: does this clifftop scene, this action of a woman sitting alone on a cliff, furnish the best opportunity for the exposition about the young men and their probing eyes? Does that exposition arise organically from the scene, or is the scene merely an excuse for it? While it’s entirely possible to imagine those young men’s eyes forming part of Easter’s experience as she sits there, either because she’s aware of them watching her at the moment, or because she’s aware of having escaped them, neither of those motives would seem to apply here. The wind tossing her hair: that’s the one thing that connects the cliffside scene to the exposition about those young men and their eyes, but it’s a tenuous connection. From there we proceed to the young men’s broad backs as they work the fields during the autumn harvest, and quiet evenings during which Easter contemplates “the rasp of a calloused hand” upon her “soft flesh.” From there we go on to some exquisitely written exposition concerning Easter’s birth and lineage: “She was herself the product of a harvest tryst”.

All this vivid exposition comes at a price: it leaves the scene of the girl sitting on that cliff in the dust. By the end of the page we’ve all but forgotten it. No wonder, since the author, too, seems to have forgotten all about it.

But was it ever really a scene to begin with? Where a true scene might occasion exposition that furthers and deepens our understanding of and involvement in it, in this case the author has given us a “pseudo-scene” the purpose of which is merely to provide a tenuous occasion for the rich exposition it gives rise to. No sooner did we engage the scene than we, along with the author, bailed out of it.

I see two solutions: either dispense with the pseudo-scene and launch us directly into exposition setting up a genuine scene, or make the cliffside scene a genuine one, an active here-and-now scene in which the exposition about the young men and their eyes is interspersed and out of which it springs organically and urgently, motivated either by Easter’s having momentarily evaded them, or by her gratified if guarded awareness that they are nearby, watching her as she sits on that cliff.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.) Here’s how to submit your first page for critique.

Note: The publisher of Your First Page is offering free shipping if you order the book directly from their site. Use code YFPfreeship.

November 12, 2019

What Makes Readers Give an Unknown Author a Chance?

Today’s guest post is by author Barbara Linn Probst, whose debut novel, Queen of the Owls, will be published in April 2020.

It’s natural to gravitate to the familiar, and it’s proven that readers tend to buy books by authors whose prior novels they’ve enjoyed. We expect to like the author’s newest book. And we will, unless our expectation is disproven.

It’s the other way around for an unknown author with no “upfront credit.” For a familiar author, positive regard is already there, although it can be lost; for an unfamiliar author, positive regard has yet to be earned.

There’s a psychological term for this. It’s called priming. In the same way that priming a wall allows the paint to adhere, psychological priming sets us up to embrace and endorse whatever we’re predisposed to like. First articulated by Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tverksy in the 1970s, priming has been widely studied in areas of human behavior from shopping to voting.

In my own experience as a university professor, I remember that the highest predictor of how students rated an instructor was whether he or she was an instructor whose course they wanted to take in the first place. In other words, if they expected to like this instructor, they did. Human beings just love to be right.

Exposure also plays a role in shaping our selections. Seeing something “everywhere” brings a sense of familiarity, trust, and inevitability. It can be hard to resist feeling that “everyone” is reading a certain book right now, so it must be good. Certainly, some debut novelists have hit that jackpot. Delia Owens, author of Where the Crawdads Sing, is a recent example.

For most new authors, however, that doesn’t happen. They have to build awareness interview-by-interview, tweet-by-tweet, hoping that readers will give them a chance. Debut novelists—and I’m one—are competing for the attention of people who can’t read every book that comes out.

When faced with an array of novels by unknown authors, why do we give some a try and not others?

I posed this question on ten different Facebook groups for readers: “Would you give a new author a try? Which of these (if any) might make you buy a book by a brand-new author?” I followed this with a list of possible reasons, asking people to select as many as they wished. Although I didn’t ask people to rank their choices, some did.

As a former researcher, I tend to dislike “forced choice” questions in which the possible responses are pre-determined; they don’t leave room for answers the researcher hasn’t anticipated. However, I’d learned from previous Facebook surveys that I would get far more responses by offering a list; it’s quicker and easier, and I wanted to cast a wide net. I’d also posed a similar question a month earlier—in a more open-ended way, without asking specifically about brand-new authors—so I already knew that a personal recommendation from a trusted source was the major reason that people choose one novel over another. This time, I wanted to understand what other elements mattered to readers—specifically, when the author was someone they didn’t already know.

One of the items on my list was “seeing the book on this and other Facebook groups.” This was, of course, a version of “recommendation from a trusted source”—and no surprise that it was one of the reasons cited most often, since I was asking the question on Facebook! The popularity of the response was circular and predictable, so I set it aside; had I asked the question at live book club meetings, people would probably have told me that they picked novels that fellow book club members had praised.

The other options I offered had to do with a book’s cover, title, awards, and reviews from Amazon, Goodreads, newspapers, and trade reviewers like Kirkus and Booklist. Within three days, over 750 people had responded.

Overwhelmingly, what made respondents willing to “give a new author a try” (other than a trusted recommendation) was the book’s cover and title: in other words, their first impression.

That didn’t mean they would end up loving the book or even finishing it, only that it would motivate them to pick it up, open it, and purchase it. Together, cover and title were mentioned more than all the other reasons combined: it accounted for 50% of responses, with some people adding a note to apologize for “judging a book by its cover.”

Many people added another reason: the short summary description that told them what the book was about. Recommendations on Goodreads and Amazon reviews were of intermediate importance. Many people explicitly said that they “didn’t trust” reader reviews, which they considered to be too subjective, not necessarily corresponding to their own taste, and suspicious—authors asking their friends to post excessively glowing reviews.

Awards and praise from newspapers, Kirkus, Booklist, and other professional sources didn’t matter very much to these readers. Awards came in lowest of all, although some respondents felt that an award was a “signal” that a book had merit.

Most people chose more than one reason. People who cited the cover usually cited title as well, suggesting that the two work together to form an overall visual impression. If that first impression drew them in, they would read the summary blurb and then decide. But if the first impression wasn’t strong, most were unlikely to proceed further.

Obviously, this was not a comprehensive survey. As with all studies, results were shaped by how the question was worded, who was asked, and how. It also reflects the perception of consumers and not the perception of bookstore owners, bloggers, reviewers, or anyone in the book trade. For those groups, media reviews and awards may carry more weight.

Nonetheless, the results offer some indications that debut authors may want to consider.

First, looks matter.

If you’re a new author about to launch, keep an eye on book cover trends; a particular look may not be your “style,” but it may be what readers are gravitating toward. Remember priming theory: if your cover resembles the covers of successful books, that might be a good thing. You don’t always have to be unique.

Experienced cover designers know what catches a reader’s attention, especially in the thumbnail versions that appear online, so listen to what they say about font, color, and composition. At the same time, it’s your book and you have the right to ask questions and to speak up if the cover doesn’t feel right. If you’re hiring your own cover designer, don’t skimp or settle. If your publisher is designing the cover for you, ask for options and for the rationale behind the various concepts. The cover should reflect the story in some way, as well as being visually pleasing.

The same is true for the title. It’s common for a publisher to change the book’s title, and the new title may feel strange or even wrong if you’ve lived with another one for a long time—as if your child started school and the teachers suddenly decided to change her name!

But the publisher may have a very good reason. Go on Amazon and search for books with titles similar to yours. If you find a long list, you may want to shift to something fresh. Go through your manuscript and look for phrases that capture an important aspect of the story. If you find a title you like, ask people what they think it means. A misleading title can backfire.

Consider where you want to focus your energy as you prepare for your book’s launch.

You can go high and try for endorsements from well-known authors or celebrities, awards, glowing reviews from newspapers and trade publications—with the idea that these will “influence the influencers” who can place your book where it will be seen.

Or you can go wide and make friends with people who host book clubs, book fairs, or online groups for readers and writers—with the idea that these are real readers who will spread the word about your book to other readers.

One strategy isn’t better than another, but you may not have the time or resources to do both. As you work to convince people to “give your book a try,” you’ll have to decide which approach suits your story and temperament.

Remember, you only get one debut. But ultimately, your aim is to move from being an unfamiliar author to a familiar one—someone who makes people say, “Oh, I just love her books!”

November 6, 2019

The Problem Confronting Memoirists: Overabundance of Material

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Submit your first page for critique.

First Page

Title: Notes from Under Water

1. How to Flee.

How did you get here? You’ve spent half your life trying to keep your mother from committing suicide, but she did it anyway, and three weeks later your husband disappeared without a word. You finally found him living with another woman, so you filed for divorce while telling yourself, no, I don’t really want to set that floozy’s house on fire and watch them both burn, when you knew perfectly well how immensely satisfying it would have felt for about a minute before you’d’ve dashed in there to pull them out of the flames, crying I’m sorry, I’m sorry. You didn’t want to be sorry. You didn’t deserve any of this. There are things you know you’re supposed to forgive, awful things, but you can’t. There are so many things to run away from right now, everywhere you look. You have fears so deep you don’t even know what they are.

But there are so many places to run away to. A beach in Xijuatanejo, where nobody can find you. You speak a little Spanish, no? Or Paris, where you once met a man on a train; Paris, yes. You were twenty-one. It was August 1972, two years before you met your husband, five years and eight months until your mother killed herself.

Jesus, what eyes. You can’t stop staring at the man on the train, with his thick, jet black hair and dark chocolate eyes, Cat Stevens eyes. He’s wearing a well-cut suit, no tie, white shirt slightly open at the neck, is traveling with an older man, and you cannot for the life of you stop. your. looking. Sitting by the window, the two men are speaking in French, and, thank god, he doesn’t see you staring. Or so you think. You, long-haired, blue-jeaned freshly minted college graduate seated in the center, are traveling on a Eurail Pass with your sister. The compartment is full, eight people sitting four per bench, face to face. My god, you have never seen a pair of eyes like his, and you silently self-scold because you cannot control your own.

An old man in a greasy coat sits across from you with a faded, floral headscarfed woman, who unwraps a smelly hunk of cheese for their lunch, merciful distraction. A noise startles everyone: ba-dingalingalingaling! It keeps ringing. All eight passengers freeze, look around, puzzled. Then you realize, oh no, it’s your alarm clock going off stupidly inside your backpack in the overhead rack. Shut up shut up, please. But it won’t stop. You cannot outwait it and let it wind down of its own accord because the others are beginning to look worried, and you recall winding it up tight this morning, so until you climb up there and shut it off, it won’t stop. You sigh and stand on the seat, reaching, blushing, so vivid you could light up the whole train. Because now you’ve got his attention, he’s on to your secret crush. He has no reason to look elsewhere but at scarlet you as you sit back down. He smiles gently and you feel a little less ill at ease, and later, he stares deep into you as the train lurches rhythmically. Your cheeks burn and you stare back at him from a place you’ve never been: naked, seeing, rocking with him in unison to the motion of the train.

Much later, he signals with his eyes for you to follow, and then gets up and leaves. Heart thumping, you wait a decent interval, worrying, is this real? Did he mean to just go to the bathroom and I’ll look like a hussy if I follow? I’ve already embarrassed myself on this train, and I would be mortified… Your sister has noticed neither your electrification nor your conundrum. You go.

First-Page Critique

This first page of this memoir presents us with not one but two opening gambits. In the first opening, a woman reflects on recent dramatic events in her life: her mother’s suicide, her husband’s disappearance, her discovery that he has set up house with a “floozy,” and her divorcing him. In Opening #2 we’re taken back “five years and eight months earlier” to a time when, as a twenty-one year-old “freshly minted college graduate” aboard a train in or near Paris, the narrator finds herself so captivated by a strange man with “Cat Stevens eyes” she follows him out of the train compartment to … she knows not where.

Apart from being well-written using the second person “you” (more on that later), what do these openings have in common? First, let’s look at what distinguishes them.

The first opening is entirely abstract. Though it alludes to emotionally charged dramatic events, it does so in a vacuum, void of setting and time, with the closest thing to action consisting of the narrator’s internal musings on those past events. By contrast, the second opening is firmly grounded in setting and scene: we have a time, a place, an event. We’re invited into an experience.

The first opening points to the tale of a grown woman’s emotional unravelling in the face of nearly simultaneous betrayals: her mother’s suicide and her husband’s infidelity; the second points to a different story, that of a young woman’s romantic coming-of-age abroad.

In content and form, like a striped blazer worn with plaid pants, instead of complementing each other, the two openings clash. Even if we assume that both stories belong to the same memoir, shouldn’t their relationship be, if not obvious, somewhat apparent from the start? Or might the whole point of juxtaposing them on the first page be to raise in readers minds the tantalizing question, “What do these events have to do with each other?”—a question that, presumably, the memoir will go on to answer? For me, however, the arbitrary way in which Opening #1 wanders into Opening #2 negates that possibility. So I turn to the book’s title for a clue. But “Notes from Under Water” doesn’t help.

Were this a novel, I could imagine all kinds of ways in which these two openings might be joined together meaningfully. A memoir allows no such inventions. The author is bounded—if not by the facts, then by her memories.

Which brings us to what I suspect is the underlying issue with this first page, one that often confronts authors when they first set out to write a memoir: an overabundance of material, and the urge to use all or too much of it. Our lives hold so many dramas, all so colorful and romantic (at least so they seem to us in memory): how to resist sharing them all? The result: a manuscript the working title of which could be “My thrilling adventures up till now.”

But a memoir is both more and less than a repository of our indelible personal experiences. Unlike autobiography, it’s shaped by an overarching, narrower, not strictly personal, theme. Our lives may supply the raw material, but a good memoir isn’t about us, or isn’t just about us. It concerns some facet of our lives as illustrated by certain experiences that readers will, hopefully, relate to. In illuminating some aspect of our shared humanity, it’s as much about the reader’s life as about our own.

As for what theme unites the experiences presented on this first page, I can only guess. I’m guessing it’s nothing more specific than the author’s eventful life. And though memoirs are distilled from lives, however eventful in itself a life doesn’t equal a memoir any more than the juice from so many grapes adds up to a bottle of wine.

* * *

Now to the second person. There are two kinds of “you” narrators, second person and second person direct address. With plain second person, the reader is pressed into service as the main character in the story. With direct address, the narrator speaks not to the reader but to another character in the story. With both approaches you run the risk of alienating your reader, in the first case by forcing them into a role they may not want to perform, in the second, by turning them into eavesdroppers listening in on a one-sided exchange between narrator and character. Often the best thing that can be said for a second person narration is that we forget that it’s in the second person and read it just as we would a third- or first-person narrative.

So why use the second person? According to narrative theorist Joshua Parker the second person “gives authors a degree of alterity from their own experiences (or desires) without having to ‘own’ them as an authorial persona.” In other words, it functions as a kind of mask or disguise—albeit not a very clever one, but one that, especially in writing a memoir, may help an author gain some distance from their material.

This was certainly the case for me in writing my own memoir. In fact, I wrote it three times: the first time in the second person, the second time in the first person, and a third time again in the second person. My wavering stemmed on one hand from my agent’s conviction that a memoir written in the second person wouldn’t sell, and on the other from an equally strong conviction—my own—that it had to be written that way.

As my agent predicted, sales of the published second-person memoir were modest. Still, were I to do it over again, I’d stick to the second person—and not because second person has since come into vogue, but because that’s the right choice for it.

All things being equal, however, I would avoid the second person, which, like antibiotics and parachutes, should be used only when necessary.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.) Here’s how to submit your first page for critique.

Note: The publisher of Your First Page is offering free shipping if you order the book directly from their site. Use code YFPfreeship.

November 5, 2019

6 Tips for Securing Speaking Engagements as a Self-Published Author

Today’s post is by author Karen A. Chase (@KarenAChase).

For self-published authors, getting your book into the hands of readers who are specifically interested in your genre or your expertise is imperative. Even if you’ve managed to get your work into bookstores, your title is one thousands of books they carry. Online, your title is one among millions. So how do you stand out? Presentations.

When you find the right venues for a presentation about your book, you are the expert that people (readers) have come to see and hear. This results in a deeper connection to you and your book as well as stronger book sales and a more robust and loyal following.

Here are six ways to secure more speaking engagements or presentation opportunities.

1. Presentations matter more than book signings.

Most authors have held at least one book signing that makes them want to give up writing altogether. The sad little table at a bookstore. The avoidant glances. The one lonely reader who tells you their whole life story and waves goodbye without buying a book.

The tiny number of book sales is barely enough to cover the container of ice cream needed to soothe your tired soul.

Presentations, however, can result in greater sales—as well as profit, if readers purchase a book directly from you that you’ve ordered at cost. So, stop signing and start speaking. Ask yourself: What is your unique viewpoint on the space-time continuum, on a historic battle, the style or voice you write in?

2. Understand your audience first.

Before you pick up the phone or send emails to inquire about speaking at a conference or an organization, take time to understand your reader (a.k.a. your target audience). If you write books about the art of knitting, do your readers attend any knitting events that happen near you? Youbetchya. (See this list of Knitting and Fiber Arts events all over the country.)

Regardless of genre, with pen in hand, write a profile of your reader, answering these six questions.

Which organizations or trade groups do your readers belong to?

Which locations or organizations host events or conferences for them?

Which percentage of your genre’s readers are men or women?

Are they typically introverts or extroverts?

What age(s) are they?

Where do they hang out or where do they share online—which Facebook groups or social platforms?

From all this you can make a list of locations where your insights might be most treasured. As an example, I write about the American Revolution, so my list includes all the “heritage” organizations, like the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Heritage groups have members that can prove they had ancestors who supported the war. Through my research, I became a DAR. The benefit of presenting to other DARs is they support their own members, and I don’t have to make them love my topic because they already do.

Bonus tip: Put writing conferences last on this list unless your book pertains specifically to the craft of writing. You need a robust and targeted audience of readers, not writers. And while book launch presentations can be at bookstores, turnout there can be scant compared to trade organizations.

3. Define your angle and develop unique presentations.

Simply reaching out to an organization about your book isn’t enough. You need to define the new perspective you bring to the same genre. And you need a plan—also written down in the form of a proposal that you can share widely—for the unique presentation you’ve developed.

Kris Spisak is a fine example; she’s the author of Get a Grip on Your Grammar. While she could have reached out to groups with presentations on why grammar matters, she instead created and trademarked Grammartopia. Spisak hosts this game-show style panel, where three to twelve contestants battle it out for grammar prowess in an entertaining and educational program. It’s as unique and fun as her book, and attendees never forget her. Furthermore, it has reach beyond writing conferences, because corporations can book her to help employees up their grammar game.

Bonus tip: Build a presentation that is authentic to you. Not everyone is a game-show hostess level extrovert like Kris Spisak. If you’re more introverted, keep reading.

4. Build your own panel discussion.

If the spotlight freaks you out, share it by inviting others to join the discussion.

The advantages to creating a group presentation are two-fold. First, it may be easier to secure a gig. My book is not traditionally published, and while that doesn’t matter to some organizations, to nonprofits on budgets I’m not a big enough draw on my own. So I’ve joined forces with two other novelists, Libby McNamee and Suzanne Adair. Like me, they are women writing about the American Revolution, specifically southern campaigns. McNamee writes young adult, and Adair also provides tours of historic sites. Our unique perspectives complement one another and for organizations who book us (three events and counting), we are viewed as a viable investment.

Secondly, the other panelists draw in potential attendees from their own audience who might not know you yet, and vice versa. That means new readers for each of you.

Bonus tip: You don’t have to pair up with other authors. If you write murder mysteries, invite experts like an undertaker and a private detective.

5. Begin outreach regionally.

If you still have a day job, you need to secure or create events close to home first. Go back to tip #2 and reorganize that list, putting all your local or regional events and opportunities first. Make special note of those that take place when you’re not working. If none exist in your area or when you’re available, this is an opportunity for you to consider creating them.

6. Contact potential venues or event coordinators far in advance.

Attendance at events is a direct result of how much marketing you (or your panelists) and the venue or organization can put behind your event. And lead time directly affects marketing.

Planning ahead gives you and the coordinators time to put together graphics, social media posts, advertising, and PR for the event. It allows time for attendees to register if the event is ticketed, and to coordinate food or beverage orders. In some cases where there is more coordination needed, like annual conferences, I’m booking presentations into summer of next year.

Bonus tip: Once you have a publishing date for your current book and especially if time is limited, reduce your writing hours for the next book and instead devote your time to connecting with readers and building presentations.

Parting advice

Ensure you post events on your website, and that you share them in your newsletter or blog. And when you get to presentations, have a sign-up sheet for your newsletter so interested attendees can follow your journey and hear about other events.

Why do all this in addition to writing? Ultimately, when done well, sharing the details behind your research, expertise, or writing can be incredibly rewarding for everyone. Moreover, if you plan on writing more books, what you need is simple. Readers. Focus your time on connecting to them via presentations, and they’ll come back for more.

November 4, 2019

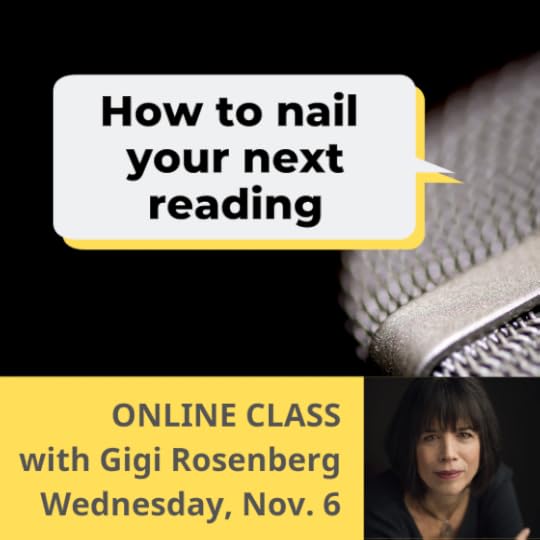

A Game Plan for How to Nail Your Next Reading

Today’s guest post is by public speaking coach Gigi Rosenberg (@gigirosenberg). She’ll be teaching a class on how to nail your next reading on November 6. Learn more and register here.

Two minutes into my first public reading more than 20 years ago in Portland, Oregon, my mouth was parched and my nose ran so much I had to ask the audience for a tissue. I stood at the podium with my lips welded to my teeth, until someone handed me a cocktail napkin and a cup of water. The rest of the reading was an out of body experience.

Until that moment, I had assumed that reading was easy. I had acted in plays and sang in musicals. How hard could it be to read aloud? I had failed to consider that for the plays and musicals, we had done hours of rehearsal. What I had attempted to do was the equivalent of showing up opening night with sheet music in my hand planning to wing it.

Since then, I’ve done many readings and even performed my solo show off-Broadway at the United Solo Theatre Festival. I’ve learned that to read well, you must train like a pro. Here’s a guide to what you need to do to show up with confidence.

Two Weeks Before: Have a Rehearsal

Rehearse in front of at least one friend. Warning: You may resist this. I hate how vulnerable I feel at this first rehearsal. But now I know that I’d rather be embarrassed in front of one person than a roomful. The more you rehearse, the more relaxed you will be. Rehearse at least once.

Give thought as to which friend you invite to this rehearsal. You want to rehearse with someone who inspires confidence, who can tell you what you did well and who can give you suggestions that leave you feeling motivated, not devastated.

Before your rehearsal, warm up your body and voice.

If possible, rehearse in the space where you’ll be reading. If you’ll be using a microphone, practice with one.

At your rehearsal, have your friend read your introduction, time your reading and practice the Q&A with you.

If you plan on standing, stand with your weight evenly distributed on both feet. If you’re reading at a lectern, practice with one.

The more familiar you are with your text, the more you can look at the audience during your reading. But don’t worry about looking at the audience.

Ask your friend: “Am I reading too fast? Can you hear me?”

Your reading voice may drone. This is common when anyone reads. If you notice this, stop reading. Have your friend ask you a question about anything, as simple as: “What did you do this morning?” Answer the question. Notice how different your voice and intonation sound when you speak in conversation. This is the voice you want—your conversational voice.

The Week Before: Confirm with Your Host

Warm up your body and voice every day. If you exercise regularly, do your routine. If you never exercise, take a walk. While walking, feel your feet hit the ground; notice your breath. Observe sights, sounds, smells. After your exercise, practice a facial and vocal workout.

Choose your outfit. Your clothes should: look great on you, feel comfortable and been worn before or at the rehearsal. You don’t want to discover during the reading that your fly unzips on its own.

Confirm with your host the following:

You’ll arrive 45 minutes before the reading. This allows time to get lost and check out the room.

They will introduce you. You can mention that you’ll write your own introduction if they would like.

How long you’ll read and answer questions.

Where you’ll sign books and that someone else will be handling payments.

A performer (which is what you are now) needs to know her choreography‚what happens when and where. Figuring out these logistics ahead of time allows you to enjoy the limelight.

The Day Of: Arrive Early and Belly Breathe

Get comfortable at the front of the room. Enjoy the view from the podium.

Practice with the microphone, if necessary. If you have a sound person, ask to do a sound check so you can hear your voice and they can check sound levels.

Place your water nearby.

Put tissues in your pocket.

Sit in the audience. Walk around the room. This is to help you get used to the space and so it can feel like it’s “yours” for the time that you’re reading.

You may feel nauseous, sweaty, shaky. This is normal. You may want to run for the hills. Again, normal.

Stretch, breathe.

If you brought a supportive friend, which always helps, talk to them. They’ll remind you that you’re prepared and gorgeous and that this is no big deal—just a rehearsal for the next reading.

If you brought a supportive friend, which always helps, talk to them. They’ll remind you that you’re prepared and gorgeous and that this is no big deal—just a rehearsal for the next reading.Note from Jane: To find out how to keep yourself focused, how to handle the question and answer, what to do if there’s a mishap, how to warm up vocally, and much more, join Gigi on November 6 for a live, online class on how to give great readings. Learn more and register here.

October 30, 2019

The Pros and Cons of Present Tense

Photo credit: soultoasty on Visual hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Submit your first page for critique.

First Page

Tonight is no ordinary night on the UNC academic calendar. Tonight is the night after classes end and the night before exams begin. A night of relief over what has ended and anxiety over what is yet to come. A night when the libraries and frat parties will be equally crowded.

I close my Intro to Marketing textbook with a thud and try to rub the tired out of my eyes. My roommate, Rachel, left our dorm room door open on her way to the bathroom to join the others. P!nk’s “Raise Your Glass” blasts from a speaker a few doors down. The girls on my hall sing along with the words and rock to the beat as they scurry back and forth to the showers filling the air with floral scents from shampoo, perfume, and hairspray.

I stuff my textbook into my backpack and hoist it over my shoulder. Marketing is my best subject. I’ve helped my parents think up ways to market the apples grown on our orchard for years, ever since the local applesauce plant closed. But rumor has it that my professor awards very few A’s. To keep my nearly perfect GPA, I need to ace the exam tomorrow. I wade into the hall and navigate my way upstream through the flow of pastel-colored robes.

Most of the faces I pass don’t know me, probably don’t even recognize me, but I recognize them. The girl who sings in the shower. The girl who plasters animal rights bulletins all over her door. The girl who sneaks guys into her room. Some of them nod politely when I catch their eyes. The rest probably don’t know what to make of me except that I’m the quiet girl who studies all the time.

My backpack accidentally bumps one of my hallmates and knocks her out of her huddle with her besties. We both stumble sideways. “Sorry!” I call over my shoulder to her. She shoots me the side-eye and returns her attention to her friends.

At the stairwell, I reach for the door handle. The bathroom door swings open behind me. “Shots! Shots! Shots!” Rachel’s loud party voice echoes down the hall, followed by the clink of glasses and laughter.

The ache in my heart returns.

With all my attention on my grades, I haven’t spent much time on my social life. So here I am. The only one left out of the fun.

Top grades will get me a top job—in corporate finance perhaps or maybe investment banking. A job where I’d never have to worry about money. A job where I’d have plenty left over to send back home and help save the orchard.

But… in two years, when I walk for graduation, I don’t want to have any lingering regrets.

I return to my room, throw my backpack on my bed, and cross the hall to the bathroom to be a part of the high-pitched excitement.

I excuse my way through the crowd, wash my hands, and sneak a look in the mirror. I’m not that different from them. Shoulder-length hair. Average height. Average size. Even though I’m not wearing a lot of makeup, I hold my own. I’m certainly attractive enough to go to a frat party.

“Oh hey—Jolene—” Rachel finally notices me.

“Where’re y’all going tonight?”

“Ummm, Phi Delt.” She cocks her head at me.

“Sounds like fun—”

“Oh, it will be.” She returns to the mirror and puts the finishing touches on her makeup. “Everyone’s soooo ready to party tonight.”

“I’ve never been to Phi Delt. Is it nice?”

Rachel flashes me the duh-look. “You’re so funny. It’s a frat house party. Believe me, it will be trashed.”

“It can’t be that bad—”

Rachel shakes her head with a laugh. She gathers her makeup and shot glass and crosses the hall to our room.

First-Page Critique

With classes over and the semester near its end, a habitually studious undergraduate faces a decision: to party or not to party? That’s the plot question raised by this opening.

But for me this first page raises a more intriguing question, one to do not with plot but with technique, namely: why the present tense? What are its advantages and disadvantages? Why is present tense so enduringly popular especially among younger writers? Has it usurped the past tense as the tense of choice for storytelling?

To answer those questions, it pays look at the history of the present tense in works of fiction.

Though its use can be traced as far back as Virgil and The Aeneid (59 BC), and it made many cameo appearances in between, it wasn’t until the first installments of Dickens’s Bleak House were published in 1852 that present tense was employed extensively in a full-length fictional work, with whole chapters of Dickens’s novel narrated by that means. Thirty-six years would pass before French novelist Édouard Dujardin used the tense exclusively in Les lauriers sont coupés, arguably the first stream-of-consciousness novel, and a primary influence on James Joyce’s Ulysses, published a generation later.

Though Damon Runyon and Joyce Cary both favored it, only after 1960, when John Updike used it for the first of a series of novels about Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom (Rabbit Run, Rabbit Redux, etc.) did the present tense gain in popularity—to the consternation of some, including author and literary critic William Gass, the title of whose 1987 New York Times essay (“A Failing Grade for the Present Tense”) makes no bones about his feelings.

Gass’s beef with the present tense came down to there being “too much of it going around.” “What was once a rather rare disease,” he wrote, “has become an epidemic.” Along with the first person and the declarative mode, Gass blamed the present tense for “that major social and artistic malaise called minimalism”—the literary movement inclined toward brevity and intensity as epitomized by Raymond Carver’s short stories and dominant when Gass’s essay was published.

Though more than thirty years have passed since then, the present tense remains as trendy as ever. For some writers—in particular students in graduate writing programs—it is the default choice, the past tense being, in their view, along with steam engines and bustles, a relic of the nineteenth century.

Apart from its ubiquity, there are good reasons to be wary of the present tense. Unlike the past tense, which allows narrators unrestricted movement between the past and the present, the present tense locks us into each moment, allowing for little if any reflection. And while the past tense lets us expand, compress, or bypass events according to their dramatic import, since in the present tense everything is happening here and now, it tends to treat all moments equally, however important or not, so a headache gets as much attention as an earthquake.

Since bringing the past into the present is crucial when it comes to evoking them, the present tense also greatly constricts the complexity of our characters, who must be evoked mainly if not strictly through their present actions. The present tense likewise restricts descriptions of settings and characters, limiting them to fleeting impressions.

Not that the present tense can’t be used effectively. For a sense of immediacy nothing beats it. Screenplays traditionally avail themselves of it. It is the most cinematic of tenses. But like the movie cameras that it replicates, it can feel icily impersonal. As for trendiness, at the risk of alienating two-thirds of my readership, for my money present tense passed from trendy to tiresome some time ago.

Of all the disadvantages of the present tense—and I’ve only touched on some here—perhaps the biggest is the inability to generate the sort of suspense that only comes with hindsight. The best example of this is provided by the Master of Suspense himself, Alfred Hitchcock. He posits two scenes in which a bomb hidden underneath a table explodes in the board room of a bank. In the first scene we have no idea the bomb is there when suddenly—BOOM!—it goes off, murdering everyone in the room. However surprising, that, according to Hitchcock, isn’t suspenseful. The second scene is identical to the first, except at some point we cut to the bomb ticking away under the table. Thus the element of suspense is introduced.