Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 84

March 19, 2020

3 Unique Research Methods for Identifying Small Publishers

Today’s guest post is by writer and publisher Rosalie Morales Kearns (@RMoralesKearns).

Back when I was seeking a publisher for my novel, finding small presses was a haphazard process. I would compile lists from various sources, only to find out that some of the presses specialized in categories other than literary fiction (poetry, for example), or hadn’t published anything in the last several years.

Now that I’ve started my own small press and am more familiar with the small-press landscape, I have some ideas about how we writers can go about not only finding small presses, but narrowing down our search to presses in specific categories that are actively publishing at the moment. (For the more traditional ways of finding publishers, see this post from Jane.)

1. Browse review venues that specialize in small-press books.If a forthcoming book from a small press is getting reviews, chances are good that the press is actively publishing right now and is effective at getting its titles into the hands of reputable reviewers. Foreword Reviews is dedicated specifically to reviewing books by small presses in many categories. Subscribe to their quarterly magazine or check out the Book Reviews section on their website, and look in the category your own manuscript belongs in—for example, YA, memoir, literary fiction, etc.

Sites like Small Press Picks, the Independent Book Review, and Melissa Duclos’s newsletter Magnify are much smaller but are also worth a look, especially if your manuscript is literary fiction.

2. Identify awards for small-press books.Looking at literary awards that are specifically for small presses will also help you compile a list of active publishers who are sending their books out for award consideration. The Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP) has its yearly Firecracker Awards specifically for literary fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. You’ll find a larger array of categories in the Foreword INDIES Book of the Year awards, administered by Foreword Reviews. Here’s the list of 2018 winners. 2019’s finalists will be announced on March 20.

3. Check bestsellers and new releases through book distributors that specialize in small-press books.A number of distributors specialize in titles published by small presses. My own press is distributed by Small Press Distribution (SPD), which represents over 400 small literary publishers. Rather than adding all those presses to the list you’re compiling, here’s a shortcut: check out SPD’s lists of new releases and bestsellers. Here are the appropriate pages for new fiction and bestselling fiction at SPD; there are also similar lists for poetry and creative nonfiction.

Also consider:

Publishers Group West offers a PGW Books in the News page. Independent Publishers Group doesn’t exclusively represent small presses, but it’s still useful to check out their New & Notable page and their Recent Reviews page. Consortium’s front page features hot news and the week’s top 12 bestsellers, and their Bookslinger blog has updates about awards and recognition for recent titles by Consortium publishers. Also check out their reading group guide page; and you can subscribe to newsletters devoted to different types of books they distribute.Ask questions or add other useful resources in the comments below. And best of luck in your search!

March 17, 2020

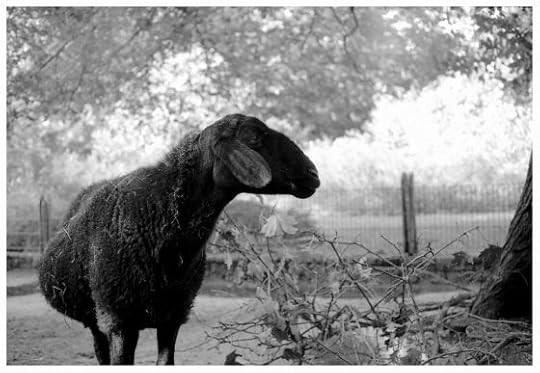

Writing Unlikeable Characters Readers Will Root For

Photo credit: irgendwiejuna on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s post is by author E. J. Wenstrom (@EJWenstrom). Sparks, the concluding novel of her four-part fantasy series, is out now.

I’m a big fan of antiheroes. A flawed character is just so much more interesting than your classic Dudley Do-Right. Anyone can like a character who makes the right choices and defends justice all the time. But that just doesn’t feel very authentic.

Can I just say it? True confessions? Traditionally heroic, always-good characters get boring.

Give me a character who struggles. Give me a character with flaws big enough to get in their way. Give me a character with complexity and baggage. This is a character that might surprise me. Perhaps not for the better—but I’ll be on the edge of my seat for sure.

I follow this mantra as much when writing my own characters as I do in my reading choices. Some—okay, most—of my characters are really rough around the edges.

But as my editor is always patiently reminding me, a lot of people don’t like unlikeable characters, on reasons of unlikeable-ness. This can be an especially perilous with female characters, whose margin for likability is even tighter than their male counterparts.

As I finished the final novel in my fantasy series this year, I gave some deep reflection to what exactly where the line is for unlikeable characters.

Can an unlikeable character still inspire readers to root for them? Heck yes—but it takes a little alchemy.

Here are a few key elements to create an unlikeable character readers will still be willing to root for:

Redeemable qualitiesEinstein once said that if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will believe it is stupid. Everyone is a genius at something. Likewise, when it comes to characters, every one has a quality worth respecting—something redeeming about them.

Elphaba was uncompromising. Dr. House was brilliant. Han Solo was charming. Redeemable traits can be found in almost any character if you spend enough time with them to understand their motives and underlying drives.

It doesn’t have to necessarily be a good quality. I enjoy Dr. House more for his wry humor at his interns’ expense than his ability to save lives—it’s just fun to watch, and I don’t have to want to hang out with the character myself to appreciate it.

If you can find and draw out these distinct qualities that make your character admirable (or entertaining), your unlikeable character will become a lot more root-able for readers in an instant.

VulnerabilityEvery character needs to show its vulnerabilities to the reader. It’s important to expose the humanity of your character—and don’t be afraid to cut deep.

If a character is despicable, what made them this way? Is it drawn from fear? A past trauma? What do they need that they have been denied?

A character who suffers can be forgiven a great deal. Who among us is our best when we are suffering or wounded?

Belief they are doing rightA character worth rooting for is a character willing to fight for something. In fantasy that fighting is often pretty literal, but it doesn’t have to be.

In real life, people make terrible choices. But most of us, most of the time, are legitimately trying our best to do the right thing. So are our characters, whether they manage to really do good or not.

Their nature, or the things that have happened to them, may make it harder to make the actions we’re used to expecting from our Knight-in-Shining-Armor heroes. But they’re doing their best with what they’ve got.

If you can get this clearly onto the page, your reader will be willing to go a lot farther with you.

Action-OrientationThis was one warning my editor gave me about unlikeable characters I took especially to heart—a character who wallows and whines through the pages is no good.

A root-able character is a character who takes action. Taking the wrong action is far better than taking no action at all (see above). Action is the momentum that keeps the story moving forward—without it, it’s going to flail, and your readers are going to lose interest.

So when in doubt, keep your character moving. Then, make them wrestle with the consequences, for good or for bad.

The Secret to Unlikeable CharactersCan an unlikeable character actually be…likeable? Maybe? Maybe not. And maybe that’s not actually the most important thing. You can get your readers behind a character they don’t want to grab a beer with—if you allow enough humanity to show through.

Ultimately, these elements help make a character be root-able despite major foibles because these qualities make these characters more like us.

Unlikeable characters work best the same way easy-to-like ones do—when we help readers to see themselves in the characters. Because a character we can recognize ourselves in, is a character we want to see succeed.

And in this way, perhaps, when that character’s relatability is rooted in how flawed they are, that ultimate victory after the struggle can be even more meaningful.

March 3, 2020

4 Reasons to Spend Time with “Bad” Books

Today’s guest post is by author Susann Cokal (@CokalSusann), whose latest novel, Mermaid Moon, is out now.

We’re all so judgy. We peer at storylines and dialogue lines and individual words, and we snort when a writer makes a choice we wouldn’t have made. We snort even more loudly at ourselves, those times when we just absolutely hate what we’ve written and think the author (Me! I’m the author!) must be an idiot. And then we’re stuck. So maybe we turn to someone else’s book for inspiration. Someone else’s good book. And then we’re more stuck than ever.

Over and over, we’ve heard that we need to read the best books first, learn from them, and apply the lessons to our own work. Never waste time with books you know you won’t like, ones that aren’t at the very pinnacle of your chosen genre or category.

This advice, like all advice, isn’t right all of the time. If the best is all you are reading, you’re limiting the sense of what writing is. You’re limiting yourself.

Here’s a wrinkle: Books you don’t like can be great teachers too. And when you’re really blocked and despairing, a bad book might give you just the help you need.

Here are four reasons why.

1. “Bad” writing refines your personal aesthetic.When you’re reading a bad book, it’s okay to let your nasty inner editor (let’s call her Judy) go to town. Let her eviscerate that best-selling whodunit with the plot holes a mile wide; she needs to get it out of her system. Dan Brown and Danielle Steel can take it; they have plenty of fans who love their work. Judy’s field day will give you a little break, and you’ll learn just as much from identifying what you don’t like as from what you do.

A gentler Judy can also show up to your workshop group and make it useful even when your writing isn’t up for discussion. By helping others identify weak spots in their work, you and Judy sharpen the eye with which you’ll read your own drafts later for revision. Being a discerning critic doesn’t mean you loathe the story or the writer, and you can honestly applaud the way each piece succeeds within its own parameters. As long as your comments are politely and helpfully phrased, it’s a win-win (a phrase often used in bad books).

2. A bad book can give your mind freedom in which to relax and explore new possibilities.Maybe you feel a bad book doesn’t deserve your full attention. That can be a boon to you too. When you’re not reading with 100 percent full focus and trying to squeeze every last lesson out of the book in front of you, your hard-working creative mind might take Judy’s hand and wander down a different path—and bring back something that helps you solve a problem in your story.

In short, bad writing might inspire you.

If you want to learn from Jennifer Egan but you’re having trouble sustaining both lyricism and a plot, try reading the latest in the Harlequin line and let the structured approach to storytelling give your overly busy creative mind a little rest. The hit-all-the-marks-right-on-schedule plot might help you subliminally with yours too. I neither confirm nor deny having done this.

Which leads to the more conscious choices in Reason Number 3.

3. Bringing in tropes from different types of writing can inject new life into yours.In recent decades, it’s become legit for literary writers to dive openly into genre writing—science fiction, comic books, pulpy mysteries, the stuff your college professors and their own Judys probably sneered at—and come back up with a long, rich novel inspired by the themes, structure, and language of those genres.

Think of Nobel laureate Kazuo Ishiguro’s riff on detective stories in When We Were Orphans, or Margaret Atwood’s post-apocalyptic Oryx and Crake, Susanna Clarke’s best-selling Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell, or MacArthur genius Octavia Butler’s seventeen books of science fiction. Where would they have been without Agatha Christie, H. P. Lovecraft, Jack Finney, and now-forgotten writers whose words swelled the pages of magazines with names like Le Zombie, Analog, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine?

And even way back when, now-canonical literary writers were already adapting genre tropes and tricks. For every House of Mirth that Edith Wharton wrote, she penned a half-dozen routine ghost stories; we just don’t hear much about them because they are, yes, “bad.” F. Scott Fitzgerald stepped into fantasy with his short stories “A Diamond as Big as the Ritz” and “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.” Virginia Woolf told ghost stories too.

So the line between good and bad may not be so sharp after all. Which brings us to:

4. The definition of a good book can change. You might change it.Writers we worship now may not have been so highly regarded in the past. I’ll give three examples: For one, Charles Dickens was the most popular author in Victorian England, but when he died, critics fell out of love with his work, even calling it “dull and wearisome.” For seven decades his reputation languished, until in 1940 George Orwell and other fancy-schmancy literary types started praising his work. Now it’s taught in just about every high school and college in the nation.

Zora Neale Hurston wrote one of the great novels of the last century, Their Eyes Were Watching God—and the world’s Judys took over thirty years to recognize its greatness. The book fell quickly out of print, to be rediscovered during the black and feminist movements.

Mid-century British author Barbara Pym published six sparkling novels of manners between 1950 and 1961, but when tastes changed, she couldn’t find a publisher. Then in 1977 she was named one of the most underrated writers of the century, and suddenly she was the It Girl. Fortunately she had never stopped writing and had several novels lined up and waiting. She fell out of favor again in the nineties but is back again now, thanks in large part to her devoted following in the Barbara Pym Fan Club.

Now it’s impossible to imagine a world in which Hurston, Dickens, and (sometimes) Pym aren’t considered to be among the great writers of the canon, that sometimes fusty list of things everybody should read. And if no one had looked back at authors deemed trivial (Pym), clumsy (Hurston), or all flash, no substance (Dickens), we wouldn’t have those books—or the thousands inspired by the writers who’ve read them.

So maybe you’ll be the one to bring a beloved writer into the canon. Maybe you’ll be that writer.

February 26, 2020

Audiobook Publishing and Distribution: Getting Started Guide for Authors

This post collects information first published in The Hot Sheet, the essential industry newsletter for authors. Get a 30-day free trial.

In 2015, audiobook sales started to enjoy booming growth in the US and UK. It was the same year that novelist John Scalzi noted that the audiobook release of his new novel with Tor outsold both the ebook and hardcover formats two to one. Indie author Joanna Penn, around the same time, noted that audiobooks represented 5 percent of her overall book sales income—on par with or better than traditional publishing.

Since then, traditional publishing has enjoyed double-digit sales growth of digital audio every year, although for authors going it alone, the results can be decidedly mixed.

How to know if the investment is right for youQuality audiobooks require significant investment (typically thousands of dollars), and the returns may be minimal to start. Before you decide to move forward, consider the following.

Sales potential is partly driven by genre and length. Mainstream audiobook subscription services, such as Scribd and Storytel, see the most activity in mystery/crime, suspense, science fiction and fantasy, personal growth, and career and money.

Indie author Cheri Lasota, who once ran an audiobook advertising business—and characterizes audiobook listeners as avid and sometimes “ravenous” fans—says listeners are lovers of sci-fi, fantasy, romance, and horror (and, to a lesser degree, mystery and historical fiction).

Indie author Craig A. Price Jr. points to science fiction and fantasy and horror as strong categories; he says, “Why did Audible select Brian D. Anderson to be the first indie author to receive a six-figure audiobook contract? His books are good, but look at them. They’re fantasy. Epic fantasy.”

In other words, audiobook length is a driving factor in the current market. Audible subscribers get one credit to spend each month, and Price says they’re going to pick the trilogy with 30-plus hours over the book with six—especially if there’s a great narrator.

In 2018, Penn reported that the majority of her audiobook sales was for nonfiction. Of her fiction audiobook income, just over half was for box sets. She says that fiction audio buyers are price- and length-sensitive, plus an increasing number of fiction audiobooks are read by top actors or big-name narrators, so fiction listeners are more sensitive to that too. “They have a lot more choice than they did a few years ago,” Penn says.

Usually your number-one criterion should be a strong existing market or sales foundation. For authors who do have that foundation, as well as the resources and ability to produce a quality audiobook, then genre and length are mostly likely to influence the sales outcome.

Quality is paramountPrice, who has listened to about two to three audiobooks per week for the last nine years, says, “A narrator really makes the book. If it sounds like the guy from the old dry-eye commercial, it makes for a rough experience.”

To retain quality and continuity, author Jennifer Ashley used the same narrator across her series that began traditional and moved to indie. She pays her narrators an upfront fee (no royalty share) at a fairly high per-hour rate, a practice to which she attributes her good sales overall. Some authors recommend avoiding the royalty-share option through Audible’s ACX (where you pay nothing up front to the narrator and split royalties for seven years), because quality narrators avoid such arrangements. But Price has been able to work around that by showing narrators a strong marketing plan and offering a more modest fee per finished hour in addition to the royalty split. Since Price started releasing audiobooks, they have outsold his ebooks.

Where to sell and distribute audiobooksAudible (owned by Amazon) is the leader in digital audio sales in the US market; authors can reach the Audible market through its subsidiary, ACX.

But Audible is far from the only player in digital audio, particularly when considering international markets. Currently, there are several dozen viable players in the retail, library, and subscription space. To reach the widest market—libraries and subscription services, especially—a distributor is required. Several options are available to authors, including ListenUp and Author’s Republic, but so far the strongest player is Findaway Voices.

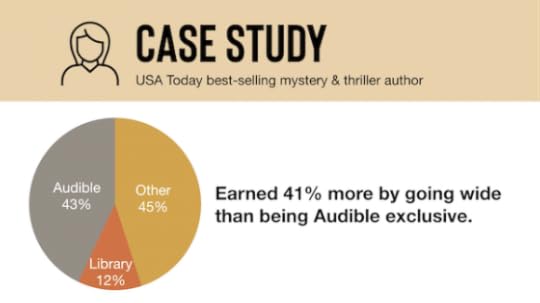

Last year, Will Dages at Findaway Voices presented an ALLi conference session, How Indie Authors Can Sell More Audiobooks, that indicates Audible represents not quite half of all audiobook sales for some authors they distribute. Partly this is because Audible operates only nine localized storefronts: US, UK, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, India, Australia, and Japan. Dages says, “For all of you who think ‘Audible, they’ve got to be 90 percent of the market,’ it’s just not true.”

In a case study of a USA Today bestselling mystery and thriller author distributed by Findaway Voices, Audible represents just 43 percent of her overall sales. Another 12 percent are library sales, then 45 percent “other.” Dages says this “other” category includes retail sales on Apple, Google, and Kobo but also streaming subscription services like Scribd and Storytel.

Authors who distribute wide can see significant earnings from libraries, particularly hoopla. Hoopla delivers digital books, video, music, and more to thousands of public libraries reaching 5 million patrons. At Digital Book World last year, hoopla said it has seen huge growth in the home use of audio. In particular, hoopla says, audio in the children’s space outperforms in libraries when compared to retail. (Authors using Findaway Voices can choose to have their works distributed through hoopla.)

Dages also says BookBub’s Chirp, which offers daily deals on audiobooks, is growing at an “incredible” rate and motivating consumers with low price points. “They are one of the most exciting things that I think is happening in the audiobook space right now. … They’re training more and more consumers that there are better places than Audible to get audiobooks.” Findaway Voices is the only audiobook distributor at this time that reaches Chirp.

We asked Score Publishing CEO Bradley Metrock, who runs Digital Book World, about the most important opportunities after Audible. He says, “I would make sure to work with a distributor who can get your audiobooks onto Google and Apple, the number-two and number-three options to me as we head into a brand new decade. Apple’s sales right now surpass Google’s in the audiobook realm. Google, however, has recently invested significant resources into audio over the last 12 to 18 months to correspond with their tremendous investments into Google Assistant and the voice/AI realm. Add to that a rise in popularity of Google mobile devices, further eroding Apple’s advantage, and I’m bullish on Google over the short-to-intermediate term for the second-best place to find audiobook sales revenue for indie authors and larger publishers alike.”

How the money worksAudible/ACX pays authors a 40 percent royalty if they are exclusive to Audible; otherwise, the royalty rate is 25 percent. When distributing directly through Audible/ACX, the author has no power to determine the audiobook price, so it’s hard to calculate exact earnings until the audiobook starts selling.

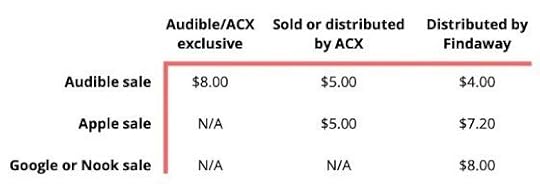

Findaway pays the author 80 percent net of all sales, on the price the author sets and controls. Retailer cut varies but is typically between 40 and 50 percent on a standard sale. For example, authors earn a 45 percent royalty on audiobook sales through Apple and 50 percent through Nook and Google Play. Here’s how the math works if an audiobook sells à la carte for $20 through various outlets:

Important caveat: Not all audiobook sales happen à la carte. Subscription services like Audible have a credit system, so payouts vary and can be determined after the fact—and payments are always lower through subscription services than through à la carte sales. Also, much of Findaway’s power lies in reaching subscription and library markets, which have varying payment models. You can explore those models here.

There are cons to going wide. Obviously, the decreased royalty rate hurts you on Audible, which is judged to be roughly 40 percent of the market; authors accustomed to 40 percent royalties will feel the pinch right away. Authors who don’t go exclusive also don’t get access to Audible promo codes—often used for audiobook giveaways to reviewers, fans, influencers, etc. While that may not seem so important, authors receive royalties for redeemed codes (yes, you read that right, you earn money on a freebie!), plus those code redemptions boost your sales rank. Authors are limited to 100 codes per title, parceled out 25 at a time.

Parting adviceThe only thing that’s for sure: the audiobook retail market is still taking shape. Last year, when Penn offered her insights into the audiobook market, she wrote, “Some authors who are exclusive [to Amazon] with ebooks are choosing to go wide with audio,” citing Michael Anderle, who founded the 20BooksTo50K group, as a prime example.

If you have signed an exclusive contract with ACX but aren’t doing a royalty split deal, you can move it to a non-exclusive contract after one year. (Email ACX and request it.) If you are on a royalty split deal, you might want to consider buying out your narrator. For more thoughts on the future of audio from the indie author perspective, see Kristine Rusch’s December post.

If you have signed an exclusive contract with ACX but aren’t doing a royalty split deal, you can move it to a non-exclusive contract after one year. (Email ACX and request it.) If you are on a royalty split deal, you might want to consider buying out your narrator. For more thoughts on the future of audio from the indie author perspective, see Kristine Rusch’s December post.

If you found this post useful, you’ll love The Hot Sheet, the essential industry newsletter for authors, published by Jane Friedman.

February 25, 2020

5 Mistakes When Writing Flashbacks in Memoir (and Fiction)

Today’s guest post is by freelance editor Sarah Chauncey (@SarahChauncey).

Flashbacks are scenes that take place prior to the narrative arc of a story. They can illuminate any number of story elements, from revealing the origins of an unusual habit to new information about a relationship. Flashbacks can give the reader a depth of context not available in the primary narrative.

Alternately, flashbacks can help the reader understand your reaction to an event in the primary timeline. For example, maybe you had a fight with your spouse, and the exchange reminded you of how you used to cower in your closet when your parents fought. While you can tell with that line, showing via a flashback can be more engaging for the reader.

However, flashbacks can be tricky to write. Written unskillfully, flashbacks can leave a reader disoriented and disengaged.

What follows are the five mistakes I see most often in memoir manuscripts, though these principles are also relevant to fiction. If you’re writing fiction, just substitute “your main character” for “you.”

1. Including irrelevant flashbacksWhen used properly, flashbacks can be illuminating. When used haphazardly, they detract from the primary narrative and leave the reader confused (or worse, bored).

You should understand how each flashback enhances the story. If it doesn’t, cut it. Flashbacks should be earned, just as any plot development is earned.

Ask yourself these three questions about every flashback in your current draft:

How does this flashback serve the story?Could the information be revealed chronologically within the time frame of the primary narrative?Is there a direct relevance to the present-day scene?Writers sometimes pepper their manuscripts with flashbacks to appear more “literary,” though from my perspective, there is nothing intrinsically literary about a flashback. I’m a big fan of chronological structure, because it keeps the reader clearly oriented. However, you may want to reveal certain information from the past at a specific, strategic point in your narrative.

A related mistake is the use of multiple flashbacks to shine light on one particular issue. For example, let’s say that you had a job as a dog walker in college. If that’s relevant to your (primary narrative) decision to adopt an English Springer Spaniel 20 years later, it might warrant a flashback. Write one compelling flashback that gives the reader a taste of your experience, but don’t create five or six different dog-walking flashbacks to make your point.

2. Writing a flashback “because it really happened”Sometimes, especially in memoir, writers want to include everything interesting that happened, and they rationalize including an irrelevant flashback by saying, “But it really happened!”

With memoir in particular, it can be difficult for a writer to discern which events are relevant to the story and which aren’t. Implausible, mind-boggling experiences that defy logic happen every day. It’s very cool that you (or the character) had that experience, but that alone is not a reason to include it in your story.

Often this tendency comes from a well-meaning place: Memoir writers typically want to be as truthful and as clear as possible. Some writers I’ve worked with have wondered whether omitting X flashback makes the story less honest or clear. It all depends on the bigger context, but in general, memoir is like carving: You start with a huge block of marble (your life experience to date) and then carve the story out from there. There’s nothing dishonest about cutting an irrelevant flashback, any more than it’s “dishonest” not to mention that you accidentally overfed your goldfish when you were five. In most cases, it’s simply not relevant to the story.

3. Forgetting to anchorOne of an author’s tasks is to keep the reader oriented in the time frame of your story. Inserting flashbacks randomly, or without “anchoring,” can leave readers adrift and confused.

To “anchor” is to use a phrase or sentence to introduce the flashback: “Twenty years earlier…”, “Before my sister was born…”, “The sound of the fire sirens took me back a decade…” The strongest anchors help the reader follow the narrator’s train of thought and connect the dots about why you’re transitioning to another time and place: Your new coworker has a vocal tic similar to your abusive mother’s. The smell of a clove cigarette takes you back to your semester in Paris. You hear a songbird from that time you went camping in northern Michigan.

Depending on the length of the flashback scene, you may need to anchor on the other side, too, to re-orient the reader to the primary narrative. Better to err on the side of anchoring too much—a beta reader or editor can tell you if you’ve overdone it—than to leave readers wondering where in your world they are.

4. Leading the reader by the noseNearly all of us—myself included—have a strong need to be understood. That often translates on the page into a final, punctuating (and telling) sentence that reiterates how you felt or one that explains your actions. For example, “My father’s stubbornness that morning infuriated me” or “I figured I was better off without Ben, anyway.”

I call this “leading the reader by the nose” and—surprise!—readers, like all of us, don’t like being told how they should feel or what they should think.

The trick is to create the scene in a way that the reader’s emotional or cognitive response is virtually inevitable. If you write it well, using characterization, action and dialogue to bring the reader into your experience, the reader will feel what you felt.

Also, no matter how much you cringe at your past behavior or worldview, resist the urge to rationalize or justify your behavior—that only comes across as defensive, and then the reader will wonder why you’re so defensive.

5. Writing recollections instead of flashbacksA recollection is a thought. A flashback is a scene. Reading about a character’s thoughts can be less compelling than giving readers the opportunity to have an experience with them. Flashbacks bring the reader into the moment with you, whenever that moment happened.

On the page, what makes something a “recollection” rather than a flashback is point of view. If you’re writing a recollection, you retain your present-day POV and reflect on an event that happened in the past. Here’s an example of a well-written recollection from Mira Bartok’s The Memory Palace:

The last time I visited my mother in a hospital, it was over 20 years ago. She was in a lockdown ward at Cleveland Psychiatric Institute (CPI) and had asked me to bring her a radio. She had always needed a radio and a certain level of darkness. In her youth, my mother had been a musical prodigy. When I was growing up, she listened to the classical station night and day. I always wondered if her need for a radio meant more than just a love of music. Did it help block out the voices in her head?

In a flashback, you create a scene as though it were happening in real time. By this, I don’t mean write it in the present tense. Rather, I mean that the scene should immerse the reader in your flashback experience. Flashbacks retain your POV at the time, rather than superimposing your present-day POV onto the memory.

Here’s an example of a skillful flashback from Huda al-Marashi’s memoir, First Comes Marriage:

In the fifth grade, I had a sleepover for my birthday (my parents’ rule was that I could have friends over, but I couldn’t spend the night at anyone’s house). When the conversation turned to my friends’ on-screen crushes, I wanted to shush them. In my house, there was nothing innocent about girls discussing boys. It wasn’t long before Mama picked up on the topic and called me out of the living room and into the kitchen to ask, “Are your friends talking about boys?”

I nodded, mortified and ashamed, and then added, “But they’re not real boys. Just actors.”

She didn’t meet my gaze. “Already?” she said, as if she were addressing herself. “These are eleven-year-old girls. What’s wrong with this country?”

That I could feel so much shame just being in the company of girls talking about boys made it clear—this was a taboo unlike any others.

Some literary memoirists skillfully weave recollections into their stories in a way that creates the same emotional impact as flashbacks. For the average memoirist—let’s say those who have yet to win a major literary prize—I believe flashbacks should be shown, rather than recounted. However, there is a place for recollections in both memoir and fiction, and not every glance backward has to be a fleshed-out flashback.

February 18, 2020

How to Build an Author Website: Getting Started Guide

Note from Jane: Next week on Feb. 26, I’m teaching an online class on author websites.

This post was originally published in 2015; it has recently been updated and expanded.

I strongly advocate all authors start and maintain a website as part of their long-term marketing efforts and ongoing platform development. But it’s an intimidating project because so few authors have been in a position to create, manage, or oversee websites. Where do you even begin?

With this guide, I hope to answer all the most frequently asked questions and make the process a manageable one.

First, decide on your website building tools and what services you’ll use (either free or paid).

When you choose your tools, consider these three factors.

Cost. Unpublished authors or those not earning much money should probably start with the free options.

Ease of use. Less tech savvy people appreciate platforms that take the guesswork out of website design and building. Unfortunately, the easy-to-use platforms often have drawbacks or eventually cost you money and frustration.

Portability and longevity. Not all platforms will stand the test of time, which is especially true of proprietary systems. (Remember Geocities? Or Apple iWeb?) Open-source platforms tend to benefit you over the long term because you’re not locked into any one service provider or hosting company. But they may be more difficult for you to learn.

My quick recommendations

If you want a free option that has already stood the test of time, try WordPress.com to start. It’s open source and powers about 1 in 5 websites in the world. It’s not going anywhere. Later on, if you need more features, you can upgrade your WordPress.com account to paid plan, or easily move to self-hosting. I comment more on the self-hosting question here.

If you want an option that’s easier to learn or use—and you have the money to spend—try SquareSpace. However, it’s hard to transition away from SquareSpace; it’s a proprietary system.

A new open-source platform that may be easy for you to learn is Ghost. It will cost you a monthly fee unless you’re advanced enough to set it up on your own host/server.

I’m not a fan of Weebly or Wix because they are proprietary systems where you ultimately have to pay to get full website functionality. If you’re going to pay for a platform, I’d learn toward SquareSpace instead. I think it’ll be around longer.

I admit to favoring WordPress—I’ve used it for site building since 2006. My 15 years of experience has made me very comfortable using it, but I am not a coder. I have never taken a coding class, and my coding knowledge primarily involves basic HTML and CSS, all self-taught.

I recognize that few authors are as comfortable as I am when it comes to WordPress. Still, I think it can be a very cost-effective option that becomes more powerful for your online presence, over time, if you’re willing to commit to learning it.

Buy your own domain

The domain is the URL where your site lives, and it should be based on the name you publish under, not your book title. Your author name is your brand that will span decades and every single book you publish. If you can’t get yourname.com, then try for yournameauthor.com, yournamebooks.com, or yournamewriter.com. If that fails, consider something other than .com (like .net or .me).

Carefully research and select a website theme or design template.

Whether you’re using WordPress or not, one of the keys to a good experience is your choice of theme. Think of a theme or design template as a skin for your website. It dictates the aesthetics—the colors, the layout, the fonts, the styles, and more. Some themes (especially WordPress themes) come with some rather incredible customizations and additional functionality, whereas very simple themes might have little or no additional functionality at all. This is why your choice is so important—it affects your overall site design but also some of your capabilities to customize your website or push it further without knowing code.

Important factors in choosing a WordPress theme

WordPress themes can be created by anyone, anywhere and made available with very little testing. Always check the ratings and reviews for each theme at WordPress, as well as if it has been recently updated or developed. You can also see how many people have downloaded the theme—and popularity works in your favor. The more people who are using a theme, the more likely the bugs are getting worked out and few conflicts exist with other third-party stuff you might use for your site. It’s also helpful if the theme has a support community where you can go to ask questions. Very new themes should generally be avoided by beginners unless it’s from a developer who has many other respected themes.

For WordPress.com users, you’ll be limited in your choice of theme—for good reason. You’ll be presented with well-tested and robust themes that are free or premium (premium themes cost you money).

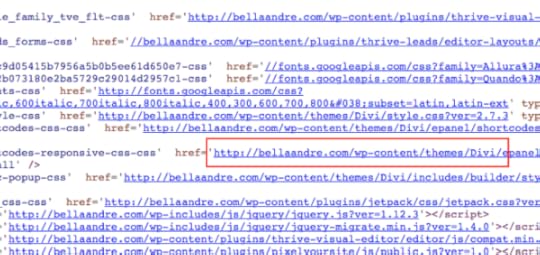

If you’re running a self-hosted WordPress site, then you can choose any theme you’re able to find in the WordPress universe, which can sometimes be paralyzing. I recommend researching as many author websites as you can, and when you find one you like, look for information about what theme they’re using. You can tell by looking at the source code. (In Chrome, go to View > Developer > View Source.) Look for the URL that indicates the theme name. For example, here’s a snippet of the source code for Bella Andre’s site:

This tells us that the WordPress theme is Divi.

Collect the following assets for your author website.

Your professional bio. If you don’t already have one, write a 100-300 word professional bio in third person that would be appropriate if used to introduce you at a reading or event. Optional but encouraged: a first-person bio that’s much longer.

Book cover images. For every book you’ve published, obtain the highest resolution image you can find. While you’ll be using lower resolution images for most of your site (to ensure fast loading time), it’s helpful to make the high resolution version available for download or as part of a media/press kit.

Brief descriptions of each book. Your book’s Amazon page probably has a brief description of your book that you can start with. If not, develop a 25-100 word description.

Long descriptions of each book. This would be the back cover copy or flap copy for your book. It’s probably around 200-300 words, or the full-length Amazon description.

Links to all major online retailers where your book can be purchased. At minimum, you’ll want to link to Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and IndieBound. Consider adding Apple, Google Play, and Kobo as well. Get links for print, ebook, audiobook, large-print, and foreign language editions.

Contact information for your agent or publicist, if you have them. Or whomever else fields requests on your behalf.

Links to your public social media profiles. If you have an official Facebook author page, or accounts with Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, Goodreads, etc., collect all of the direct links. Don’t bother with accounts where you’re not open to being friended/followed by the general public.

Your best blurbs or reviews. Collect any praise that appeared on the front or back cover of your book, or official (positive) reviews your book received from the media.

Create the critical informational pages for your author website.

We’ll get to the homepage next, but aside from the homepage, you’ll want the following:

About page. Add your professional bio. Also include a professional headshot if you have one; if not, a casual shot will do fine. Your about page can have several sections if you like—mine does.

A page dedicated to each of your book titles. Always show the cover image, but keep the resolution low (e.g., less than 500 pixels across) for basic display on your site. If you like, make the high-resolution version available for download or as part of a media kit. Add a brief description of your book; layer in blurbs, quotes, or praise that help indicate it’s a great book; and add buy buttons leading to all the major retailers. If you want, add the long description, too, and/or include a link to an excerpt—usually the introduction or chapter one. If there are any ancillary materials related to your book (book club guides, FAQs, etc), make sure those are readily available and linked to from the book page.

A page dedicated to each book series (if applicable). Make it easy for readers to see the order of books in the series and figure out which ones they’ve read. Plain chronological order (the order of release) typically works best.

Contact form. Unless you’re super famous and trying to avoid new opportunities, make it clear how you can be contacted. I recommend a contact form. If appropriate, add your agent or publicist’s contact info as well—or anyone who might handle communication or requests on your behalf.

Craft your homepage.

What appears on your homepage will be highly dependent (at least at first) on the template or theme that you choose. A simple homepage design will have the following elements:

A clear identity or header. This boils down to your name, tagline (“New York Times bestselling thriller novelist”), and possibly a headshot. This header will likely appear on every page of your site, depending on your theme. Ideally the visuals tie into the work you publish (e.g., book cover designs, themes in your work, any official branding you use). Multi-genre authors, or authors who have multiple types of audiences, usually face difficult choices about what to prioritize and what messaging to use. Your homepage will typically be more effective if you focus on appealing to the audience that you want to grow or if you focus on the type of work that you want to be known for. Other types of work may have to take a backseat, at least as far as the homepage is concerned.

The cover of your most recent book (or even all your books). Visitors should see or be introduced to your most recent book (or the book most important to you) on the homepage, without having to scroll or click around to find it. Ideally, visitors can click straight to their favored retail site to make a purchase. Alain de Botton’s homepage manages to encompass the author’s many different books and interests at a glance. Andrew Shaffer puts several book covers on the homepage. However, don’t assume people will scroll down a long homepage. Make sure you have a “Books” tab in your menu/navigation so people can quickly jump to or scan all your titles without scrolling.

Links to social media sites where you’re active. If you have an active presence on Facebook, Twitter, or elsewhere, include clear icons somewhere in the header, footer, or sidebar of the page where they can be found quickly. It’s OK to link to just one site if that’s the place where you prefer readers engage with you. Avoid linking to social media sites where you have an account, but don’t engage or actively post.

An email newsletter signup. The most important part of your sign-up is the language you use when asking people to subscribe. Avoid a generic call to action, such as “Sign up for my free email newsletter.” Instead, craft the copy in such a way that no other author could use the same language. Make it unique to you and what you send. See James Clear’s site for an example of how to do this in an elegant manner.

Social proof. This can be as simple as a brief quote from a brilliant book review. Or let’s say one of your books was an Oprah selection—that would go front and center. Some authors just stick with “New York Times bestseller” (assuming it’s true).

(Optional) A super brief description of who you are. Here’s the description on author Scott Berkun’s site: “Scott Berkun is the bestselling author of seven books on culture, leadership and how ideas work. You can hire him to speak, ask him a question or follow him on email, Twitter and Facebook.”

Homepage design tends to be very subjective. The most important thing is that the type of author you are—and the type of work you produce—be recognizable quickly. You don’t want visitors guessing at who you are; you have about 3 to 7 seconds to convey a message before they leave. So don’t get too clever or cutesy with how you state your identity.

Make the homepage navigation or menu system absolutely clear—which usually means having a clear path for people to find out more information about who you are (“About”), how to contact you (“Contact”), and what books you’ve authored (“Books”).

If you blog

Some authors who blog will put their blog front and center on their homepage—or it will end up there by default! This can be a mistake unless your blog is current, popular, and compelling. For most authors I work with, it’s far better to have links to their most recent blog posts apparent on the homepage, and use the homepage to more prominently focus on books. If you decide to have your blog take up most of your homepage, I recommend that you not show the full text of each post. Instead, show an image + excerpt and make people click through to read, so you have room to feature a range of latest posts (without making people scroll forever).

If needed, to change your homepage settings on WordPress (to avoid it showing a default archive of blog posts), go to Appearance > Customize > Homepage Settings.

Customize and personalize your site.

You might not have the resources to do this right away, but it’s helpful to hire a designer to create a custom header image, or otherwise create a custom look that fits your personality and books. This post by Simone Collins offers insight into what this means.

Continue improving your site over time.

Nearly all website building systems make it easy to update your site as you have new ideas or new ways of communicating what you do. Don’t expect to get it perfect the first time; expect that you’ll improve the site incrementally the longer you live with it. You’ll visit other authors’ sites and begin to pick up on subtle details you never noticed before; you’ll want to incorporate their bag of tricks into your own site.

For instance, many authors incorporate “social proof” into their header images—you see the logos of major media outlets that have featured their work. You might not really take notice of this until you have your own site, and realize you want to reflect the same kind of “social proof” that your work has earned.

This is so important I’ll state it again: improve incrementally. Your website is never finished. It is always a work in progress. You’ll improve it, tweak it, experiment with it, and hopefully take pride in how it showcases your work.

If you’re unpublished

All the same principles apply, except you might have a more stripped down version of your site than outlined here. Instead of dedicated pages to your published books, you might have a page devoted to projects in progress, or list shorter works that have appeared online or in print. It’s better to get your site started now, while you’re unpublished, so you own your domain early on, learn how to use the tools, and begin the journey of expressing who you are within digital media environments.

Other considerations

To add e-commerce functionality to your site, you won’t be able to remain on free website plans. If you plan to accept payments directly through your site (known as e-commerce functionality), that’s when you should consider investing in an upgraded WordPress.com account or a self-hosted website. (SquareSpace sites have e-commerce functionality baked right in.) WooCommerce is a WordPress plugin-in that facilitates e-commerce on your site. As for me, I use Gravity Forms + Stripe because my needs are very simple. Keep in mind that, if you do accept payments directly, you need a secure site. Check with your site hosting company about how to do this.

Cheap hosting is OK for low-traffic sites, but outages may be common, and support not so supportive. Years ago, I started out my website on a very cheap hosting plan from GoDaddy. It worked fine and did the job for less than $100/year, but eventually I bought a better hosting plan from SiteGround with additional functionality, such as site staging (so you can easily build a site without it being live), automated nightly backups, and improved caching to improve my site speed. I now pay $1500/year, a cost that’s mostly determined by my site traffic. With cheap (or cheaper) hosting, you might not find your site uptime as reliable, and the support might be lacking. With managed hosting plans—which tend to emphasize their service and support for site owners who aren’t techies or experienced web developers—the added expense can be worth it for peace of mind. WPEngine is a good example of WordPress managed hosting.

WordPress users: only use plugins that you really need. Plugins are bits of functionality that you add to your site. They may be extremely simple, such as a widget that shows the most popular blog posts at your site, or they can be very complex, such as message boards and forum systems—or WooCommerce, which adds e-commerce functionality. Whatever functionality you’d like to add to your site, you can bet there’s a plugin that does it—probably a dozen plugins! And therein lies the challenge. It’s up to you to figure out which one might look best or work best on your site. Plugins may or may not work well with your theme, or they may cause your other plugins to be disrupted. You rarely know what the outcome will be until you try. That’s why it’s important to research your plugins just as you do your themes. Especially if you’re a beginner to site building, choose plugins that are popular and regularly updated, and preferably offer some form of support.

If you’re self-hosting your site, install Google Analytics and use Google Search Console. Google Analytics tracks and reports your website traffic. The tool is free and only requires that you have a Google account in order to get started. It’s best to install it from the very beginning even if you don’t see a need for it; Google Analytics starts tracking on the day it’s installed and can’t be applied retroactively. Most authors, once they’re a couple years in, want and can benefit from the data that Google Analytics offers. Something not done as often, but that’s also valuable, is registering/claiming your site through Google Search Console. You can connect Google Search Console and Google Analytics for improved reporting. While Google Search Console is more advanced than what most authors will be able to understand, it still offers functionality you’ll want over the long term. In the short term, use it to send you alerts when Google has problems properly indexing/accessing your site for search purposes.

If you encounter roadblocks or problems, Google it first. This is my No. 1 secret web development tip. I solve about 90% of my website problems or frustrations by searching for error codes, error phrases, or simplistic explanations of the problem I’m having, along with the keyword “WordPress.” More often than not, I find someone else who has encountered the same problem and solved it. If that doesn’t work, I resort to the support community provided by my WordPress theme developer.

For more on author websites

Self-Hosting Your Author Website: How and Why to Do It

10 Ways to Build Long-Lasting Traffic to Your Site or Blog

Your Homepage Is Not As Important As You Think

A Good Memoir Is an Act of Service

Today’s guest post is by Julie Lythcott-Haims (@jlythcotthaims), excerpted from her foreword to Writing Memoir, a new book of writing prompts by the San Francisco collective The Writers’ Grotto.

Memoirists take on the risks associated with telling truths in public, and thus are the bug lighters of the literary world. Critics love to pick on us—they equate the genre to a gathering of nudists whose bodies no one wants to see. Family and friends can be critics, too—they may not like the secrets being revealed or the way they’ve been depicted on the page. But whether memoirists are lauded as heroes or reviled as knaves is beside the point. The truth is worth telling. And sometimes the truth hurts.

Whereas in a novel the reader is aware of three distinct points of view—the author who writes the book, the perspective from which the story is told, and the main character or protagonist who lives the story—in memoir, the author, narrator, and protagonist are one and the same. This requires a bit of psychological sorting, and embedded in the complexity is a critical lesson: A memoirist’s central preoccupation is determining what the self knew (and when) and how the narrator should reveal the protagonist’s journey to the reader, while doing a delicate dance with the changing nature of memory.

Unlike novelists, memoirists choose not to invent a world where anything goes and where the author will have complete deniability. Our oath is to the truth. Yet truth is not as ironclad a concept as it may seem. Think of it as fact versus perception; this seems like a clear distinction, yet is my perception not the pencil that records the facts of my life?

Following Thanksgiving dinner, for example, were you to ask all of your relatives to spend half an hour writing down what happened during the meal, you would get as many versions of that truth as there are relatives. Each of us sees things differently, through the lens of our experiences, biases, fears, and needs. The Thanksgiving scene—who arrived when, who sat where, the food, the conversation, and what caused that clatter in the kitchen—is now part of the past.

The only means we have for resurrecting it are the memories of the humans who were there. Memory, therefore, is a representation (a re-presentation). Even if the whole thing had been recorded and watched on instant replay in the family room, we might know the what of what happened, but we still wouldn’t know the why and the how. Why Uncle Rufus showed up late and how Mom felt when she heard him come through the door. Why Dad had a smirk on his face. Why cousin Iona grew silent. How Emmett felt as he sat there. How, when all was said and done, there was a pile of potatoes on the kitchen floor. Is anyone’s conclusion on these matters more right or wrong than anyone else’s? Not really.

Moreover, we are biased either toward or against ourselves and others; we can’t know what we do not know and often don’t know why we did something, let alone what motivated someone else’s behavior. And what we do know is, by definition, only what our memory has chosen to retain for us. Memoirists aim for accuracy, honesty, and fairness, knowing certainty is impossible to come by.

How to begin summoning the best memories you’ve got

Give airtime to the memories that just won’t quit—the ones that form the basis for your impulse to write memoir.

Be curious about investigating the deeper story and harvest the best memories from conversations, interactions, events, experiences, inner feelings, and dreams.

Press on your joy and moments of triumph and ask yourself why those times were so eventful—they are clues as to what matters most to you.

Press on what hurts in order to understand what you fear.

The material you can’t bear to face or write about could ultimately form some of your most impactful writing. See if you can go there. If you don’t, you might make the mistake of telling the story that stands in front of the story that actually wants to be told. Dig up not just what happened to you but what you did to others. Tell yourself you can always take the hard bits out before anyone sees—for that is true—and it will also give you time to get comfortable seeing that stuff on the page.

You have to be okay with your flawed self, and all of the flawed selves in your story. You also have to be fair to everyone else. As my editor told me when I was writing my memoir, “Be the God of all characters,” by which she meant care about everyone equally. Look at every interaction from all angles. Make sure you’re not portraying yourself in rich complexity and everyone else as stereotype. My editor also meant I had to be realistic about myself. She told me, “Readers won’t trust you or root for you unless they know about some of the stupid, shitty, and shameful things you have done.” It felt like a paradox—how are they going to like me if I give them a reason to hate me? But I came to understand her point. All humans are flawed; a willingness to show your own flaws on the page makes you all the more relatable.

Inspired? Scared? Good. Give over to the inner plea: “Something happened to me and I think others should know about it.” If this plea comes with the wild scream of ego needing attention, you might want to check yourself. (Memoir writing can be a wonderful catharsis, but do you need to inflict it on others? Maybe you just need to spend a lot of time writing in your journal.) Yet if the plea comes with quiet certainty that this topic bridges your human experience to that of others—sharpen your pencil. Humans yearn for connection, community, and meaning, and can find it in the well-told stories of others. Hold your primary readers close to your heart. If they know how tamales are made or how black hair should be handled, don’t overexplain it; let those who don’t get it look it up. Put differently, a good memoir is an act of service. The human condition in its alienation, pain, and joy yearns for a faithful scribe. Memoir offers readers that ultimate safe harbor: the knowledge that they are not alone.

3 memoir writing prompts to get you started

Make a list of lies you’ve told, from the small innocuous ones to whoppers that changed the lives of others.

List twenty things you’ve wanted to accomplish in life. (Learn Spanish? Travel to Machu Picchu? Get a dog?) Now cross off those things you’ve already achieved.

List physical characteristics that define you, and how you and others have commented on them.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed today’s post, be sure to check out The Writers’ Grotto’s entire Lit Starts series: writing prompts for memoir, dialog, character, action, humor, and sci-fi/fantasy.

February 17, 2020

Subscription Marketing for Authors: A Primer

Today’s guest post is by Anne Janzer (@AnneJanzer), author of the newly revised Subscription Marketing. While her book is targeted at businesses getting into the subscription market, this excerpt contains valuable advice for authors seeking to build a relationship with their audience.

Much ink has been spilled about how businesses benefit from subscriptions: predictable revenue streams, tighter customer relationships, and more. Nearly every industry now participates in this rapidly growing sector of the economy. Start-ups launch with subscription models, while established businesses are now jumping in. And services like Substack and Patreon make it possible for everyone—including unpublished writers—to get in on the action.

But you need to plan carefully if you want to see results.

How subscription marketing is different from traditional marketing

Traditional marketing strategies focus on leading people to the initial sale. Subscription businesses shift their focus from the point of sale to the long-term, ongoing customer relationship. The subscriber remains a prospect, deserving ongoing engagement and nurturing.

That means, in the Subscription Economy, you’re only doing half of your job as a marketer if you focus on the sale and ignore the reader. If your income depends on subscription-based relationships, then it’s time to adopt the mindset and strategies of subscription marketing.

Subscription marketing resets fundamental ideas you may have about marketing. For example, as a subscription marketer:

Leads are fine. Relationships are better.

Large marketing budgets are helpful. Creativity is priceless.

Interrupt-driven tactics like advertising deliver inconsistent results. Adding value always works.

Chasing sales is exhausting. Creating value, however, is energizing.

When you’re starting from near zero, nurturing readers seems like a problem for the distant future. But the best time to think about retaining your readers is before you’ve acquired them.

If you want to growth-hack your way to success, work on attracting the right readers from day one. Demonstrate and nurture your readers’ perception of value, and they’ll do the marketing for you.

Here’s how to market your subscription, whether offered through Substack, Patreon or some other platform.

Add value through content. Master the skills of content marketing; they will help you both attract the first readers and nurture them once they’re on board. Great content need not be expensive. A large budget is lovely, but creativity and empathy are available at any budget level. If you can imagine your ideal reader’s perspective, you can create digital books, blog posts, videos, and other content that they’ll love.

Add value through community. Build a community around you, and you’ll achieve multiple objectives: nurturing readers, attracting new ones, encouraging word-of-mouth, and even reducing costs. Most important, you’ll be creating value in relationships between people.

Share meaningful stories. Stories form strong connections. Tell your origin story; develop a brand story; share reader stories.

Share your values. Pick a cause and stand up for it; this can help you earn trust and might deliver earned media you could not otherwise afford.

Nurture free trial and freemium readers. Subscription relationships are built on trust and value. If you’re relatively new, readers may not have enough information yet to trust you. In this situation, a free trial or freemium offering can go a long way toward both establishing trust and demonstrating value.

A world of churn

Churn is what happens when customers leave, or recurring revenues vanish. Churn is the enemy of growth. For every subscriber who leaves, you must find a replacement before your new signups represent growth.

Churn is often the difference between success and failure.

We sign up for services because they are convenient, fun, or affordable. But there are just as many reasons to cut back or unsubscribe. Again, a quick glance into your personal life illustrates the pervasiveness of churn.

Do you ever sign up for a free trial of software that looks interesting, only to forget to use it? (I’m guilty of this one.)

Do you subscribe to online content, then months later, overwhelmed by all the messages in your inbox, go on an unsubscribing binge?

Do you periodically look for ways to dial down recurring subscription costs?

In transactional business models, marketing and sales organizations worry about losing new sales to competitors. In a subscription business, because subscribers pay over time, they decide repeatedly to remain a customer (renew) or leave for a competitor (churn).

A relentless focus on churn (or, if you’re an optimist, its counterpart: retention) is the duty of every marketer in a business with subscriptions. High churn numbers represent an opportunity. If you can reduce churn rates through marketing campaigns or customer success efforts, you can have a significant and lasting effect on revenues and growth.

As your readership grows, replacing subscribers who leave becomes more difficult simply because the numbers increase. If you’re serious about growth, get serious about managing churn.

What if growth isn’t your primary objective?

Most authors, speakers and consultants should focus on nurturing value (not growth), because long-term success is built on relationships, referrals, and returning clients.

I first encountered Paul Jarvis when I took his online MailChimp course. Jarvis writes software, teaches online courses, and is the author of the wonderful book Company of One. He uses that term to refer to any business that questions growth as its main objective. Jarvis writes:

Too often businesses forget about their current audience—the people already listening, buying, and engaging. These should be the most important people to your business—far more than anyone you wish you were reaching.

As a participant in the Subscription Economy, “companies of one” have many advantages over larger organizations. Sure, you may not have the budget of the big guys, but you have something that they don’t: yourself.

Email-based subscription models

Many authors provide goods or services that don’t easily fit a subscription billing model. Perhaps your work lends itself to individual projects rather than ongoing subscriptions. You might sell a few online courses or derive most of your income from one-time transactions or book royalties.

Still, you can find a way to embed subscription relationships into your business. Don’t worry about linking revenue to the subscription at the outset. Focus on building those subscription relationships instead. If you’re not ready to add a membership or subscription offering, consider starting with a simple, non-revenue-producing subscription relationship: the email subscription.

An email subscriber pays you with the currency of attention by giving you permission to send messages and by opening and reading your emails.

However, doing email well can be tricky. To see what I mean, look at the marketing emails in your inbox right now from a subscription perspective. Some are spammy; they abuse your trust by trying to sell, sell, and sell.

Others deliver real value. They’re informative or funny. Some are welcome reminders of your relationship with the sender. Those are effective value-nurturing emails.

Seth Godin is a prolific author and a genuine thought leader in the marketing space. He emails his subscribers every day. Yes, every day. These posts (which live on Seths.blog) are short, but inspiring. By showing up and providing value daily, he earns the right to occasionally tell his subscribers about his latest courses and books.

Why do all this work when there’s no revenue tied to it?

If you’ve read this far, you know one answer: Use emails to sustain and nurture relationships with existing and past readers, and future ones.

The discipline of regularly producing content for your audience forces you to put yourself in their shoes, learn about their issues, and empathize with their situations. This makes your future work better, whether you’re writing books, coding software, or crafting furniture.

This email list can also be the gateway to subscription revenue. For example, the email content may become part of something bigger, like a book or podcast. Godin’s book What to Do When It’s Your Turn (and It’s Always Your Turn) curates and compiles inspirational posts from his blogs in a beautiful package.

Or consider premium email subscriptions. You might offer both free and paid email subscriptions, giving paid subscribers early access, personalized input, or extra content.

While the revenue from paid subscriptions may be small, the benefits are outsized. For example, Jane Friedman publishes The Hot Sheet, which puts her at the forefront of publishing industry news, and connects her with people in her industry and beyond. It reinforces her core value as someone who understands the publishing industry. She is making a subscription product from the ongoing research she would do anyway.

And even if you’re earning revenues, the primary benefit of a subscription email may be the opportunity to forge a closer connection with your audience. People who pay to subscribe to your blog will put aside the time to read the emails more carefully and will contact you with questions or insights.

Parting advice

Large organizations often struggle to put a human face on the brand. They may rely on spokespeople or talking geckos to personify the brand. They worry about fonts and logos. You’ve got something better than a logo—yourself. Add value to every interaction by being yourself, as part of any subscription offering, even if you rely on automation to simplify your operations.

February 6, 2020

When Revising Your Novel, Look for These 4 Problem Areas

Photo credit: David de la Mano on Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s guest post is an excerpt adapted from The Novel Editing Workbook: 105 Tricks and Tips for Revising Your Fiction Manuscript by Kris Spisak (@KrisSpisak).

Editing is energizing, where you take your solid creation and nudge it into brilliance. It’s taking a pile of words and shaping it into something that resembles the story you envisioned. Sometimes, a book looks mighty ugly in its early draft form, but even rough, flawed words are so much better than a blank page. You’ve already conquered the blank page. No problem, right? Now it’s time to push up your sleeves again. Here are four exercises to help you notably improve your story.

Ensure your protagonist has agency

We all want to be active players in our own life, right? Not someone pushed around by everything that happens to us. Characters are the same way. Reading a day-by-day accounting of someone is not as thrilling as reading a day-by-day, turn-by-turn, twist-by-twist story of a character taking charge of whatever situation they are in for better or worse, for guts and glory.

Do things happen to your character, or are they an active player in the story? A powerful protagonist should not only react to different circumstances. They need to make choices on their own. They need to have agency. They need to be an active player in their own story.

All of a character’s choices and actions do not need to be the right choices and actions. Sometimes a choice fits a character’s sense of self and their motivations, but this action is still something that can make your readers hold their breath. That terrible choice not only can redefine who they are as a character in a moment of struggle, but it may create a turning point in the plot of your story. Your reader might further connect to them as a flawed but relatable individual because of that terrible choice. We all try to be good people. However, if you write a perfect protagonist who is always doing the right thing, that’s not a very exciting story to read.

Exercise: Find all of the moments in your story where the direction of the plot changes because of a character’s choice. If you can’t find any, you have some work to do.

Reassess your sitting and talking scenes

Dialogue can sometimes be the best part of a book, but the story needs to lead the way, not the characters repetitively talking it out.

Discovering things about yourself, your world, the meaning of life, or the meaning of the clue that answers the murder mystery all within a conversation might be a life-changing for a person but not always for a reader. Readers are pulled into stories. Wait, let me clarify that. Readers are pulled into stories when they are transported into a moment with your character, experiencing the same hopes, fears, anticipation, and every other emotion by that character’s side.

Brilliant dialogue is something to celebrate, but remember your job as a novelist is to craft more than only brilliant dialogue, especially when that dialogue is not surrounded by anything that actually happens. If you’re writing a novel, you can’t forget the character’s story, the problem driving the plot, and the internal and external forces at play.

Sometimes sitting-and-talking scenes—in a car, at a diner, on a park bench, leaning on a pillow, or anywhere else—are either talking for the sake of talking or talking for such a duration that the story’s plot and its urgency are lost.

Actions speak louder than words. It’s true for your characters as much as yourself.

Exercise: Seek and destroy sitting-and-talking scenes. Just kidding. Well, I’m only kind of kidding. They should only exist rarely and only make the final cut if something is accomplished in that conversation more than a review of happenings or a Socratic dialogue.

Review the scaling of emotions

Every one of us can be set off in one way or another under the right circumstances. But you should be careful with characters who go from happy-go-lucky to irate within the beat of a single sentence.

Sometimes writers forget that emotional build is necessary. Imagine watching an angry character slowly become calmer then pacified then intrigued by something then excited about it. That emotional variance within a single scene can pull a reader in if you do it well. If you don’t, it becomes jumpy, and your characters become a little manic—and that’s not what you’re going for.

Exercise: Every time your characters have a shift in emotions during the scene, reexamine how you do it. Is it too fast? Do you allow your readers time to go on the emotional journey with your characters? Allow them to see and experience the subtleties that trigger the changes.

Strike the realizations

Some words indicate the writer is cheating. Do I mean cheating where whistles are blown and flags are tossed onto the field? No. Though, if I had my way, it might be something like that. I mean “cheating” because the writer is taking the easy way out, and their writing suffers for it.

When it comes to the word “realize,” would you rather have your reader hear about what is being discovered, or would you rather have your reader make the discovery along with your characters? What is more exciting?

What is more powerful: a line about a character realizing the solution to the mystery or a moment that allows your reader to have the same epiphany as your protagonist at the same time?

What will strike your reader more profoundly: an injustice experienced through a scene or the pointing out that something is not fair?

What might draw your reader in more: the witnessing of the exact second she understands she loves him or the narration where this revelation is explained to the reader?

It’s harder. It takes more time. But it pays off.

Exercise: Search out the word “realize” in your manuscript—and when I say search out the word “realize,” I actually mean to search out “realiz” because if you stop at the “z,” you will catch the words “realize,” “realized,” “realizing,” and every other version that might pop up. Of course, “realize” is not the only epiphany-weakening culprit. Think about other wordings you use in the same way too. Then take these opportunities to elevate the possibilities. Your reader will appreciate it.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out Kris’s new book The Novel Editing Workbook: 105 Tricks and Tips for Revising Your Fiction Manuscript.

February 4, 2020

Using Partnerships to Help Land a Nonfiction Book Deal

Today’s guest post is by Aimee Aristotelous, co-author of Almost Keto.

When I started writing a book on food and nutrition, I assumed potential publishing houses would perceive me as qualified enough to author a book. After all, I’m a nutritionist. But I received countless rejections. I realized I needed something more than just credentials or expertise.

As I perused the aisles of health, nutrition, and cookbooks in Barnes and Noble, trying to figure out who the published authors were, I saw that most were celebrities, MDs, or PhDs. So I decided I needed one of those highly regarded terminal degrees attached to my book. Finding and securing the right type of author partnership isn’t easy, though. Here’s what was instrumental in my process.

Choose the type of partnership that’s right for you

There are several ways to partner on a book.

Co-author. While you can have a co-author who will be responsible for writing a large portion of the book, this is basically like choosing a business partner, so choose wisely. My husband is my co-author on my second book and he is probably the only person I know who I would co-author with. Choose someone you know extremely well and have a formal contract that covers every possible aspect of the partnership. (Here’s a co-author contract template from the SFWA.)

Contributors. Alternatively, you can reach out to contributing writers who offer snippets of commentary and provide insight on areas where you don’t have much expertise. For example, in one chapter of my pregnancy nutrition book, I discuss nutritious introductory foods for a six month old, and one contributing writer, a pediatric nurse, gave added commentary about the mechanisms of the a newborn’s gastrointestinal tract.