Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 85

January 31, 2020

Want More People to Support Your Book? Don’t Make These 2 Mistakes.

Photo credit: floeschie via VisualHunt.com / CC BY

In my latest column for Publishers Weekly, I discuss how authors must refine their approach when seeking support from influencers or the media. (I call this “earned media”—where you get attention or coverage for free. Sometimes publicists help with this.)

First, never assume that the influencer needs to read a copy of the book—or have a copy—in order to support it. Not true. I write:

Consider that reading a book takes hours of time that someone might not have. Though it may seem counterintuitive (and some authors are hurt by the implication that not everyone is eager to read their books), if your targets already know you or your work very well, don’t put them on the spot to read the book. They may already be prepared to support you. Of course, you should always offer to send a copy. Just don’t make that central to your ask—e.g., “May I send you the book?” Instead, think about what you’d like to see happen if they agree to support the book. Do you want them to tweet about it? Post on Instagram? Have you on a podcast?

There’s a second mistake that gets made—read the full column to find out what it is.

January 29, 2020

Jane’s Guide to Getting the Most Out of a Writers Conference

2019 Emerging Writers Festival (L to R: Ally Kirkpatrick, Michelle Koufopoulos, Jane Friedman, Laura Chasen)

I’ve been speaking at writers conferences since 2001. Most years I travel to more than a dozen, and I’ve seen it all, from the biggest events to the smallest. (Scroll to the bottom of my speaking page and you’ll find a running list.)

Here’s what I’ve learned over the past 20 years about making the most of any event, whether you’re an attendee or a speaker.

How to Choose the Best Writers Conference for You

Before you select a conference (or get seduced by its advertising or speaker list), first identify your primary goal in attending one. Most goals fit into one of three areas: improving your craft, networking with others, and pitching agents/editors.

Few conferences can prioritize these goals equally; most market to one goal. For example, the Writer’s Digest Conference in New York City, hosted at a Midtown hotel, offers a pitch slam that features dozens of agents and editors who are there to hear your pitch. Sure, you’ll do some socializing and networking, but it’s a large event with attendees staying all over the city—and thus harder to experience a feeling of community.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the Midwest Writers Workshop in Muncie, Indiana, on the campus of Ball State University, has to cap registration at less than 300 writers. Agents and editors attend, but most of the conference is focused on improving one’s craft and building a supportive community. Intimacy of the environment contributes to that goal.

Once you can articulate your motivation for attending a conference, it’ll be easier to choose one. Here are factors to consider.

Your genre. The vast majority of writing conferences offer programming that’s generally inclusive of all genres, which is not a bad thing, but it can quickly affect the quality of your experience if you need genre-specific guidance. In fact, you can get steered in the wrong direction quickly by a generalist who doesn’t know the special needs or demands of your genre. That’s why children’s writers should strongly consider SCBWI events, if only because more of the programming is tailored to your needs and focused on your genre’s market considerations.

Faculty and speakers. Look for speakers who write in your genre or have accomplished goals that look similar to what you’d like to achieve. Keynote speakers can be entertaining, inspiring, and drive publicity, but the real learning tends to come in the breakout sessions, master classes, or sessions with the speakers who may not be big names. Avoid committing to a conference before the speakers and sessions are announced, assuming your goal is to deepen your mastery of the craft or business. Good rule of thumb: If a keynote speaker failed to show up, would the conference still be attractive to you?

One-on-one feedback or critique. Some writers conferences offer consulting and critique appointments with editors, agents, and other professionals. These can be a cost effective way to receive either editorial or business guidance, but be careful. Agents and editors may be seeing dozens of writers during the conference and may not spend much time on advance preparation, even if you pay to send materials in advance. Conversations can be rushed. The onus is often on the writer to make the appointment useful and direct the conversation in a way that’s beneficial. I’ve seen such meetings offer significant insights and advantages, but for some they can be terribly damaging. Don’t forget that agents and editors are fallible—these appointments shouldn’t be the final word on you or your work.

Agent and editor pitches. Similarly, these can be fun, anxiety-inducing, and soul crushing. I comment at length in a separate post.

Jane speaking at SCBWI 2019 Los Angeles. Photo by Nutschell Anne Windsor

Venue. A majority of writers conferences take place at hotels. If they’re not at a hotel, they’re likely to be at a university. It’s almost always to your benefit to stay at the conference hotel if there is one—it will reduce stress, save valuable time, and increase networking opportunities. If you cringe at the thought of networking, or don’t have the vaguest idea of how to do it, here’s great guidance: Schmoozing for Introverts.

Location. To save on costs, you may want to stick close to home, but there’s also another big benefit. If you meet other writers at the event, they’re more likely to be from your area, too—making it easier to form relationships and collaborate over long periods of time, as your careers grow alongside one another. If you go to a big-city or nationally known conference, attendees are more likely to be from all over the country. That might be to your benefit if you’ve tapped out your local and regional connections and want to expand your network to a national level.

Size. If you want a small, intimate experience, without the feeling of getting “lost,” look for conferences that cap registration around 200-300, or that simply don’t draw more than that number. A small conference is not an indicator of its quality or potential to further your career; evaluate the faculty and programming to help answer that question. Large conferences, where attendance exceeds 600 or so, can feel overwhelming for new writers especially, but may offer more diverse program selection. When attending a large-scale event, look for pre- and post-conference master classes with more intimate gatherings. That can give you the best of both worlds, if you can afford it. Side note: Small, retreat-style events can help you with a deep dive on a manuscript or offer intensive study on a specific topic. In such cases, you may be working with only one teacher, so be confident it’s someone you respect or trust. An application process in these situations is a good sign, to ensure a good experience for everyone. Ask past attendees about the environment and overall vibe if you can.

Cost. I’ve seen no correlation between the cost of a conference and its value. Usually, price is driven by the cost of living in the conference city and how chic the venue is. (Airport hotels often get used by writers conferences for a reason—it’s cheaper to run an event at one.)

Years in operation. The longer a conference has been running, generally the better quality you can expect. The staff or host organization learns over time what works or doesn’t work for their audience and their venue, and they’ve incorporated feedback from attendees into their programming. Beware of attending a conference in its first or second year, especially an expensive one. You may have a great time, but the staff is likely still working out the kinks.

Pre-Conference Prep for Attendees and Speakers

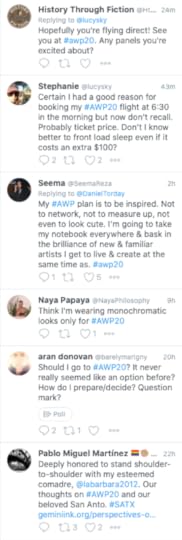

If one of your conference goals is to network and develop better community relationships, then pre-conference prep is critical. If you’re not on social media, now is the time to establish at least one account. The big writing conferences have ongoing Twitter conversations months before the actual event. This is your opportunity to warm up the networking fires and make your conference time all the more valuable.

Find out the conference hashtag. Ask the organizers what the hashtag is if it’s not clear from their website or social media accounts. (Usually it will be mentioned on Twitter.) If they don’t have a conference hashtag, ask them to assign one and publicize it. You’re doing them a favor.

Find out the conference hashtag. Ask the organizers what the hashtag is if it’s not clear from their website or social media accounts. (Usually it will be mentioned on Twitter.) If they don’t have a conference hashtag, ask them to assign one and publicize it. You’re doing them a favor.Research the speakers—especially those you hope to meet in person. At minimum, read their bios. (This actually makes you more prepared than the majority in attendance.) Remembering even a small detail about someone’s publishing history or background is invaluable if you stand in line next to this person at the bar or sit with them at a meal. A benefit of conference-going is making connections you wouldn’t otherwise have. Speakers will be flattered and an instant friend if you know a little something about their work, especially if they’re not a conference headliner. And while you’re at it, read up on the conference organizers, too. They put in a ton of work behind the scenes, and if you show you’re paying attention, you have a lifelong friend.

On social media: Post that you’re going to the event and use the conference hashtag. Sometimes you may want to tag the conference too (for smaller events), assuming they have a social media account. On occasion, post what you’re looking forward to or how you’re preparing, and tag the presenters if appropriate—on Twitter especially this can be rewarding. You’ll likely identify and start conversations with people who could be conference buddies when you get there (helpful if you’re attending solo). As the event draws closer, more people will be using or searching the hashtag and they will find your posts.

Pick your first choice and backup workshops. I suggest you make selections before you enter the hectic energy of the event. Almost every conference posts the full schedule at their website.

Pre-conference prep for speakers

One of the reasons people speak at writing conferences—which can pay little and sometimes nothing—is to network and get face time with others in the industry. Far in advance, study the bios, websites, and social presence of the speakers and look for what you have in common. Can you envision future collaborations with any? Opportunities for you both? Just like I described for attendees, post on social media prior to the event. Start building connections early. That way, a conversation has already been established once you arrive on the scene.

If you’re on a panel, collect the social handles (Twitter and Instagram, usually) of your other panelists. Start promoting the panel in advance and tag your panelists. Use the conference hashtag.

For a big conference, where there’s lots of advance social chatter, you can ask attendees what they’re hoping to learn. You can even work attendees or other speakers into your presentation if appropriate (in a constructive way!); this makes people feel extra special that you’ve gone the extra mile to customize your talk for them. (This advice is stolen from Rand Fishkin, see tip #13.)

Take note of influencers in attendance who might be important to you or your community. Meeting them in person can be like rocket fuel if, in the future, you ever pitch that person a guest post, ask if you can be on their podcast, etc. (Do not pressure them at the conference if you’ve never met. Build the relationship first. Be a human first.)

Check and double-check the A/V situation and room setup. Ask what tech will be available in the room. Ask about the projector if you have a slide presentation, VGA vs. HDMI adapters, screen size, screen aspect ratio (4:3 or 16:9?), etc. Ask even if you don’t need to know, because the responses will give you an idea of the conference’s sophistication and if it’s ready to handle your needs. Prepared conferences will have you complete a form about microphone preferences, room setup, and A/V requirements—and also warn you if certain things aren’t available (like wifi).

A cautionary note about panels

They can be terrible for everyone involved—moderators, the panelists, and the audience. They are hard to do well and get overused by conference programmers.

The best use for a panel (IMHO) is when the topic demands diverse viewpoints or the whole point is to get as many voices as possible on an issue. A panel is needed, for example, when you’re trying to give writers a sense of market trends or how agents or publishers want to acquire different things. Pitch panels are popular and a great use of the format.

A panel is a terrible idea if you’re trying to teach the fundamentals of something, like how to perfect your first pages or build a good author website—lots of conflicting opinions can just confuse the audience and leave them with no idea how to proceed.

The success of a panel often depends on its moderator. A good moderator knows the differing viewpoints and strengths of the panelists, and understands the questions and priorities of the audience. They know how to frame issues, offer context, and illuminate areas of disagreement in a way that’s insightful rather than confusing.

Too many moderators wing it and let the panelists moderate themselves—or even let the panelists come up with the questions. Bad idea. If you’re in a position to moderate, never put the burden on the panelists to drive the conversation. This will result in the most vocal or opinionated panelists taking over.

Pitch panel at the 2018 Erma Bombeck Writers Workshop, with The Book Doctors, agent Kate McKean, and Jane Friedman (this was a good panel)

Setting up meals and other informal get togethers

Advice for attendees: Most speakers don’t have time for one-on-one meetings or appointments outside of what the conference provides for. Avoid requesting such meetings in advance unless you know for sure the speaker is open to them. If you’d like to try and get some informal chat time, conference mealtime is your best opportunity: maneuver your way to a seat at their table. However, see section below on home-turf advantage for other ideas on what you can do.

Advice for speaker-to-speaker invites: Other colleagues may be open to meeting up, especially if they would recognize your name; just be aware that conference commitments may limit everyone’s free time and some speakers travel with family. If the conference doesn’t provide all meals or you notice large blocks of down time in the schedule, it might be useful and a welcome gesture to coordinate a group outing with speakers free and available to join. It also avoids the pressure of a one-on-one if you don’t know each other well.

For both attendees and speakers: If you have conference downtime that you’d like to use for networking or socializing (and especially if the conference has open schedule gaps of 2+ hours), put out a call on social media with the conference hashtag. For example, let people know you’re going to visit the local independent bookstore at 4 p.m. before dinner, and invite anyone who’d like to come along.

If you have home-turf advantage

If there’s a conference in your town, then you have home-turf advantage. That means you don’t even have to be an attendee of that conference to potentially benefit from the out-of-town talent that’s coming your way. You can potentially invite a speaker out to a meal or for some other type of break from the conference. (But it has to be a real and desirable break—not a sneaky way to get a free consultation.)

Big red flashing light warning: It’s impossible to know the speaker’s existing commitments, travel schedule, or how much free time they have. You should never presume they’re able to get away from the conference, even for a couple hours. And they may treasure the few moments they have to themselves. Still, the further they are from home—and if it’s their first time in a city they don’t know—the more likely they might appreciate an outing with a local, whether you’re a conference attendee or not.

If you plan to approach a speaker with such an idea, your chances of getting a “yes” increase a thousandfold if you’ve already had a series of positive interactions, even if it’s just online through social or email. Invites from total strangers get ignored.

With Vicki Stiefel in Los Angeles

Sometimes it’s better to avoid a direct invite, in fact. You could open up a conversation by offering tips about the neighborhood they’re staying in—like what restaurants are good within a quick walk or cab ride. You could offer to help with any transportation needs they might have. And so on. Then see where the conversation goes.

The other (easier) option is to arrange a group outing or meal for multiple people (speakers, attendees, or a mix), and you act as host. Group outings take the pressure off as long as no one feels “stuck” somewhere. Make it easy for people to retreat back to the hotel or conference venue if needed.

Some of my favorite conference memories involve meeting authors in person I’ve mainly known from online interactions, such as Janie Chang in Vancouver, Alison Williams in Dubai, and Vicki Stiefel in Los Angeles. Each of these lovely people emailed me and suggested an outing to which I agreed.

Attendees: What to Take to a Conference

Business cards. It seems old fashioned, but these remain useful. Include your name, website, and social handles. I like to put the cover image of my book on one side of the card (full bleed).

A note card with your elevator pitch. Even if you’re not pitching, it helps to work on a distilled version of what your book is about—then memorize it. Keep it handy on a note card if you get nervous. You’ll get asked a lot about what you’re working on, and you need a strong answer. You want people to remember you for this.

Something for note taking. Paper journal or laptop, whatever you like.

A selection for a reading. Many conferences have attendee readings. It doesn’t hurt to be prepared if you’re into that sort of thing.

A book (print). Print is important here so that people can see who or what you’re reading. Few things are better for striking up a conversation at a writers conference.

Some other conversation starter. If you’re a shy person, consider if there is something you can wear (a shirt, a pair of socks, a piece of jewelry) that can help draw like-minded people to you.

Speakers: What to Take to a Conference

Books for sale. The conference organizers should provide you with information on how their conference bookstore works—whether you bring your own stock or if it will be ordered and sold by a bookseller.

Your introduction. Even if the conference asks you to provide an introductory bio prior to the event, also bring your own copy to the event in hard copy form. You never know if the person introducing you will be prepared; if not, hand them your bio. This also allows you to customize the intro based on the event and topic.

Business cards. Make sure it includes your email and key social media accounts. Book cover images on one side are ideal.

Giveaway. If you want to build your email newsletter list, bring a giveaway item for your session (your book or others’ books, blank journals, a nice pen, etc). It could also be digital, like a code to download a free ebook. At the beginning of the session, have people put their name and email address on a slip of paper then draw a name at the end of the session. Let people know they don’t have to include their email address if they don’t want to.

A copy of your book(s), plus a display stand. Prop this up during your session or panel so everyone can see the book cover clearly. Alternatively, you can pass out a promo item that has your most recent book cover on it. This could include business cards, bookmarks, postcards, or handouts. Don’t let anyone leave your session without seeing your book cover!

A/V solutions and backup solutions (h/t Carol Saller). If you have a slide presentation, bring it with you (on your laptop and/or thumb drive) and also have it saved in the cloud. Bring VGA and HDMI adapters if you’re using your own laptop. Think through worst-case scenarios: What if there’s no projector or screen in the room? What if there are no handouts? Etc. It never hurts to email the conference one last time to check on tech if it’s critical to you.

During the Conference

Live tweet or write and post about the conference on social; tag or link to speakers as appropriate. Most speakers are delighted to get the free publicity if you tweet about their session, but keep your ears open for anyone who says “No tweeting” or similar. (And of course be judicious about what you share; the speaker shouldn’t feel that you’re weirdly profiting from sharing their advice online.)

Live tweet or write and post about the conference on social; tag or link to speakers as appropriate. Most speakers are delighted to get the free publicity if you tweet about their session, but keep your ears open for anyone who says “No tweeting” or similar. (And of course be judicious about what you share; the speaker shouldn’t feel that you’re weirdly profiting from sharing their advice online.)Immediately after a session—for speakers whom you admire or would like to build a connection—go up and briefly introduce yourself. Thank them for the talk and mention anything valuable you took away from the session. If it was an incredible session, say so, but there’s no need to flatter. Remember: this exchange has to be brief if you want to remain charming and if lots of other people are waiting. After the conference, the speaker is much more likely to engage with you and remember you if you introduce yourself after their talk.

Take selfies of yourself and others at the conference—both other attendees and speakers. Post using the conference hashtag.

Attend the mixers, social hours, etc, as much as your energy allows. Don’t be afraid to take your book with you if going alone. It will help you strike up a conversation with others.

Right away, follow on social those you meet; it helps you not forget them and stay in touch.

Reminders for speakers

Use the microphone, use the microphone, use the microphone—even if you think you don’t need to, for accessibility reasons.

Make handouts or slide presentations available for download. This provides good value and helps with accessibility.

Post-Conference

Follow up with anyone you’d like to stay in touch with, but not immediately. Wait at least a week, even more; people need time to catch up after being away.

Send friend requests or make other social media connections if you haven’t already. You don’t want to forget about the people you met and this makes it easier to get together in the future.

If you have a blog or a podcast, consider doing a summary of the best advice or tips you took away from the event. However, be respectful: if you’re sharing a large amount of information from a single person, it’s best to ask permission to share it widely. The best time to do that is immediately after the presentation—approach the speaker and ask if they’re comfortable with the sharing you have in mind.

Just for yourself, summarize a few important takeaways from the conference or concrete next steps you’ll want to take, while the conference is still fresh in your mind. Give yourself specific deadlines or hold yourself accountable for acting on what you’ve learned.

Don’t Be That Person

Pitch only during appointments or opportunities reserved for pitching. Agents and editors do not want to be pitched outside of those times. If you’re chatting with an agent or editor at the bar or during a meal, talk about what you’ve read lately, what you’ve learned at the conference, or ask them for their perspective on a publishing industry issue. Do not pitch them unless they explicitly ask about your book. Even then, keep it brief. Make them ask questions if they want to learn more. You’ll impress them far more that way.

Avoid complaining loudly about rejections, past pitch experiences, any unfavorable interactions with agents and editors, etc. You never know who is listening at a conference, and the writing and publishing community is very small indeed. Save the complaining for the people you know well or can trust to offer advice or sympathy. (That said, if something happens to you at a conference that ought to be addressed by the conference organizers—instances of negligence, abuse, or discrimination—tell them.)

When you ask questions at a session, don’t deliver a long soliloquy that’s not really a question. Try to keep the question brief and also general enough that everyone in the room might benefit from the answer.

Agents, editors, and other speakers may politely accept your book or manuscript if you hand it to them at a conference, but this is rarely a good use of your resources or precious copies. (I do wonder how many books like this end up with housekeepers and janitorial staff.) If you feel certain someone should have a copy of your book, follow up after the conference via email and ask if they prefer a print copy or digital copy.

Do you have advice for making the most of a writers conference? Let everyone know in the comments.

January 27, 2020

How Partnerships Can Help Boost Your Pre-Orders: Q&A with Nina R. Sadowsky

Today’s Q&A is by journalist and romance writer Cathy Shouse (@cathyshouse).

Nina R. Sadowsky (@sadowsky_nina) is a recovering entertainment lawyer who worked as a film and television producer and writer for most of her career. She has written numerous original screenplays and adaptations and done rewrites for such companies as The Walt Disney Company, Working Title Films, and Lifetime Television.

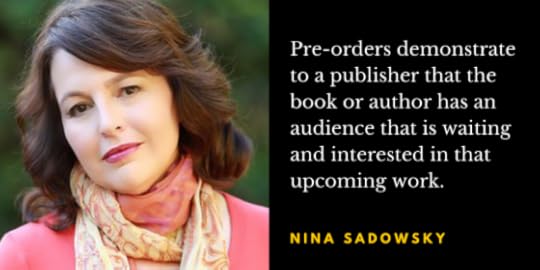

In March 2016, Ballantine released Nina’s first novel, Just Fall, a psychological thriller. Fast forward to January 28, 2020, when Sadowsky’s third thriller, The Empty Bed is about to come out. It’s the second in the Burial Society series. Recently, she answered questions via email about ways she is promoting her book to increase pre-orders.

She’s not the only one. Bestselling Author Lisa Scottoline recently let book buyers who pre-ordered choose a paperback from her backlist. Dana Kaye, founder of Kaye Publicity wrote in her current newsletter, “Pre-orders play a part in an author’s chance to be on bestseller lists. First-week sales are extremely important to media outlets such as the New York Times. An author’s pre-order sales count toward their first week’s sales, which can bump a title’s potential for a bestseller list ranking.”

Cathy Shouse: What is your most significant effort right now to boost your pre-orders?

Nina Sandowsky: Since my protagonist rescues whistleblowers, abused women and other vulnerable and desperate people on the page, I teamed up with the Violence Intervention Program, a Los Angeles organization that helps the most needy (featuring as it does everything from a fetal alcohol clinic to an LGBQT+ center to an elder abuse clinic) to do some good in real life. I will donate a portion of every pre-order to the organization when proof of purchase is sent to EmptyBedVIP@gmail.com.

Pre-orders are particularly important because they demonstrate to a publisher that the book or author has an audience that is waiting and interested in that upcoming work. That demonstrated interest of course affects the number of books ordered in an initial run, but also the marketing and publicity support the publisher brings to the work.

This perspective is largely anecdotal, as traditional publishers like mine can be very close-mouthed about both print runs and marketing expenditures, although my publisher has always welcomed my innovations toward generating pre-orders, supporting my efforts with social media support and book bundles.

Many authors will donate to a charity associated with the book, but you truly went all in with the Violence Intervention Program. Tell us more about that.

My Burial Society series is a form of wish fulfillment for me with my protagonist, Catherine, serving as my badass avatar. I go to marches and sign petitions. She takes action, sometimes morally questionable action, in her aid of the most vulnerable in our society. I wanted to take Catherine’s spirit out of the fiction realm and into reality, so I partnered with the Violence Intervention Program (VIP) and its LGBTQ clinic, the Alexis Project, for the release of The Empty Bed.

I have several connections to VIP: the first is that my dear friend, the extraordinary Robin Sax, is the project manager at the Alexis Project and has been integral in developing its mental health services.

The second connection is Alexis herself: Alexis Arquette starred in the first movie I produced, Jumpin’ at the Boneyard, and her sister Rosanna Arquette was featured in my second. When Alexis passed away in 2016, Rosanna partnered with VIP’s fearless leader, Dr. Astrid Heger, to create the Alexis Project.

Once I had the idea for the promotion, I contacted my friend Robin Sax, who arranged an introduction to Dr. Heger. I toured the VIP facilities so that I could speak firsthand about the amazing work they do. I spoke to Rosanna, who gave me a quote to be used for promotional purposes, and I conducted an exclusive interview with her which will be released as part of my first podcast series this month through my newsletter and on my website. I created social media promotional materials which were shared on my platforms and also by Ballantine/Random House and VIP. VIP also highlighted the promotion through their newsletter and Random House offered to sponsor a raffle for a book bundle in conjunction with the promotion.

I’ve heard that some organizations are wary of having their names promoted in this way and are reluctant to help authors publicize. They have expressed concerns about the book’s contents and/or its themes. Did you experience any of that, even initially?

VIP and the Alexis Project have been very welcoming of my support. I gave Rosanna, Dr. Heger and other key members of the team advance copies, but that was not required by the organization.

Have you received feedback? Has the response been different from what you expected and if so, how?

I’ve received a lot of supportive comments and no negative ones. One reaction that I’m a bit stumped about how to address is that people who have wanted to support VIP and the pre-order promotion have ordered the book, but haven’t taken the extra step of emailing their proof of purchase to EmptyBedVIP@gmail.com. And they should. Because when they do, they get a digital packet of rewards, featuring a “killer” book club guide with recipes, cocktails, invitations, and discussion questions, in addition to my making a donation to the work of VIP.

How will you weigh whether this latest initiative was successful?

My initial goal was to raise pots of money for VIP. We’ve got until January 28 and I’m promoting hard until the end. Even if I don’t succeed—whatever the outcome, I’m happy I’ve succeeded in making more people aware of the vital work done by the organization. In my writing, I am always trying to address issues of social justice, and so promoting an organization I care deeply about fired up my marketing drive.

What are some other methods you’ve used to encourage pre-orders and how have they worked?

Although it’s difficult to directly gauge the impact of any marketing effort, I’m constantly trying new things.

I created swag items for both The Burial Society and The Empty Bed and distributed these to influencers, at conferences, and through giveaway promotions.

I’ve experimented a bit with the type of swag, trying to determine what provided the best bang for the buck. While I’ve created canvas tote bags, scented candles, luggage tags and notebooks that were all branded with cover art, the most successful choice was the lens cleaners that I ordered for The Empty Bed. Inexpensive to purchase and mail, and useful to everyone, these have been hugely popular. In fact, I expect to see many copycats at Thrillerfest next year, as that is where I debuted the lens cloths last July to a great reception from other authors!

Since market research tells us it takes 7 to 10 impressions to create awareness and then convert that awareness to a purchase, putting my branding on something that everyone uses daily seemed like a smart move.

Another promotion I tried was a short story contest, 500 words around the topic of “secrets.” The winner got books and swag from me and I enlisted my publisher to send a gift box of other books as an added bonus.

Again, I have no empirical data that tells me if the contest converted to sales, but it was great fun reading the entries! When I received the stories, I asked someone else to sort the entries into a file with the authors’ names concealed, as I was uncertain of the reach of the efforts I had put into publicizing the contest and was afraid I would know all of the writers. While I did end up knowing a few, most of the contestants were unknown to me, as was the first-prize winner.

Since I believe that an author builds an audience one reader at a time, this kind of personal engagement with my growing fan base is an important part of my overall strategy. And my publisher has seconded this, emphasizing that a small, highly engaged fan base can work miracles in spreading the word about a book.

Is there anything you are thinking about doing differently next time around or do you know yet?

I’m still evaluating the success of this promotion, both for my pre-orders and for VIP. I’ll continue to be innovative about how to promote my books because I feel that it’s a necessity to do so. As I have another thriller coming out this summer, Convince Me, I’m sure I’ll be cooking up some fresh ideas pretty soon!

January 22, 2020

Here’s a System and Template for Tracking Your Submissions (Bonus: It Reduces the Sting of Rejection)

Photo credit: lealingo on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Photo credit: lealingo on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-NDToday’s post is by author Emma Lombard (@LombardEmma).

Throwing your new manuscript into the query trenches can be an exhilarating but nerve-crushing experience. I use a systematic and business-like approach to help take the sting out of rejections and keep me focused on moving forward with querying.

Before querying, I ensure my manuscript has been through multiple revisions, critique partners, beta readers and edits to give it its best shot. I also have a polished and professionally critiqued query letter.

1. Find agents who represent your genre

Here are some sites where you can research agents online:

Query Tracker: free service that has a paid option

Manuscript Wish List: aggregates agent and editor conversations that happen on Twitter using the hashtag #mswl

Publishers Marketplace ($25/month)

#PitMad pitch parties on Twitter

Helpful Hint: Properly screening the right agents takes an extraordinary amount of time! Start collating your list of agents during your breaks while you are finishing off the last of your revisions or edits on your manuscript, or else this task will seem monumental if you leave it to the last minute.

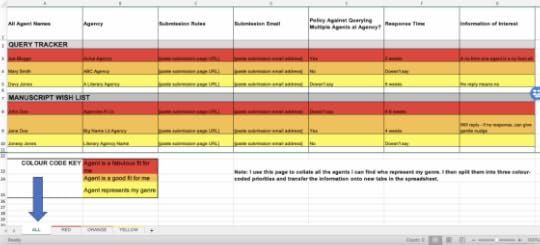

2. Create a spreadsheet to track queries

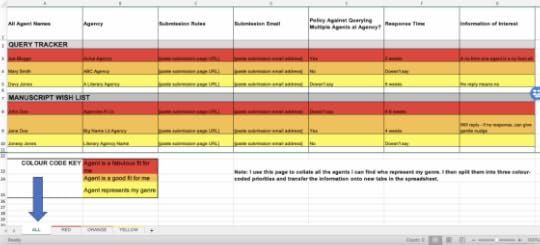

Keep track of all suitable agents, including their contact details and submission rules. Here’s a ready-made tracking spreadsheet template for you to download. Feel free to modify it as required.

How to Use the Spreadsheet or Set Up Your Own

First, I create four tabs on my spreadsheet. On the first tab, “All,” list all agents who represent your genre. Categorize agents depending on where their details are found, and fill out the info in the corresponding columns.

Columns under the ALL tab

Columns under the ALL tabAgent Name

Agency

Submission URL: I don’t enter submission details into the spreadsheet in case they change. I refer to the live URL when the time comes to query that agent.

Submission email: this might be different from the agent’s normal email address

Policy on querying multiple agents at the agency

Response time

Information of interest: jot down any interesting tidbits along the way

Within each category, prioritize the agents by highlighting them:

Red: agent is a fabulous fit for me

Orange: agent is a good fit for me

Yellow: agent represents my genre

Helpful Hint: Even if an agent is currently closed to queries, still add them to your spreadsheet. By the time you get around to querying, they may be open again.

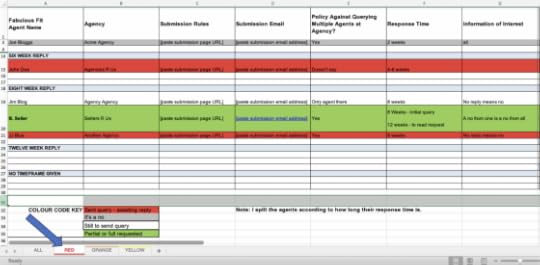

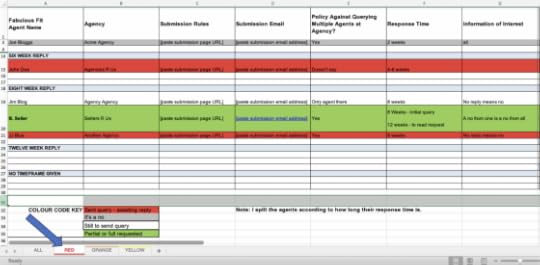

Your other tabs: red, orange and yellow

Your other tabs: red, orange and yellowNext: Transfer the color-coded agents from the ALL Tab onto their own tabulated sheets (red, orange, yellow). Remove all the color highlights after you do this.

Then: Categorize the agents by their response timeframes. Send out queries in batches of ten, ensuring they have different response times, so that responses will start to roll in at different times.

Then I color code the query rows based on the status; I change the color as new information comes in. These are the colors that I use:

Red: Query sent, awaiting reply

Green: Partial or full request

No color: Still need to send query

Gray: No

I add the following columns of information:

Date first queried

Requested materials sent

Date to follow up

Date to cancel query

Response

If a rejection comes in, highlight the agent gray and immediately send a new query out to another agent. Try to keep ten queries out there at all times. Keep the rejected agents on the spreadsheet so as not to double query them.

Helpful Hint: In the Red, Orange and Yellow categories, pick your top 10 agents who you’d like to query first and place them at the top of the spreadsheets.

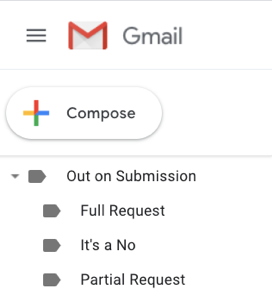

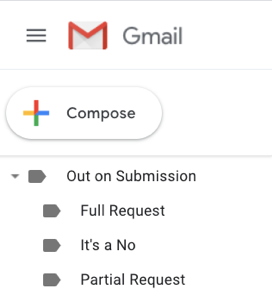

3. Create separate email folders

To keep track of all the emails that come and go, create a main folder with subfolders in the email menu so that they don’t clutter up in the sent and in boxes.

Out on submission: for all sent email queries

Full request: to see who is reading fulls

No: move all correspondence for an agent who says no into this folder

Partial request: to see who is reading partials

Helpful Hint: Set a goal of how many agents you plan to query. For example, I have screened and collated 170 world-wide agents on my three color-coded spreadsheets, and I’m not giving up until I’ve queried every single one of them!

Remember, it’s just business

I find that by using a systematic color-coding system to track queries, and by filing my emails, it’s not as disheartening when a query is rejected because I have a call to action in place to immediately send another query out.

Getting into a business frame of mind helps. It’s a bit like keeping a balance sheet: money in—money out. Or submitting bids: you win some—you lose some. My favorite quote from a literary agent on the topic of query rejections is from Janet Reid (aka The Query Shark), on her Rules for Writers guest post on my blog:

.ugb-0634daf .ugb-blockquote__quote{width:70px !important;height:70px !important}.ugb-0634daf .ugb-inner-block{text-align:left}.ugb-0634daf.ugb-blockquote{margin-top:47px !important;margin-bottom:-49px !important;padding-bottom:0px !important}I tell you this here to illustrate one more time that when you query agents and you get a form rejection, it’s not always about YOU. It could be about ME.

It’s ME if I’m not enamored of the topic no matter how well written;

It’s ME if I’m overwhelmed with work this week, and just can’t read one more partial;

It’s ME if I’ve got a project very similar to yours and can’t sell it for spit;

It’s ME if I can’t think of an editor who would buy this book and have no idea where to even start;

It’s ME if a colleague handles this genre and I don’t want to encroach on his/her turf.

I don’t tell you any of this, and I don’t apologize for using a form rejection in these cases. I do, and you’ll just have to know that.

Janet’s advice helps me focus on the fact that a query rejection is not personal—it’s just business!

How to Take the Sting Out of Query Rejections

Photo credit: lealingo on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Photo credit: lealingo on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC-NDToday’s post is by author Emma Lombard (@LombardEmma).

Throwing your new manuscript into the query trenches can be an exhilarating but nerve-crushing experience. I use a systematic and business-like approach to help take the sting out of rejections and keep me focused on moving forward with querying.

Before querying, I ensure my manuscript has been through multiple revisions, critique partners, beta readers and edits to give it its best shot. I also have a polished and professionally critiqued query letter.

1. Find agents who represent your genre

Here are some sites where you can research agents online:

Query Tracker: free service that has a paid option

Manuscript Wish List: aggregates agent and editor conversations that happen on Twitter using the hashtag #mswishlist

Publishers Marketplace ($25/month)

#PitMad pitch parties on Twitter

Helpful Hint: Properly screening the right agents takes an extraordinary amount of time! Start collating your list of agents during your breaks while you are finishing off the last of your revisions or edits on your manuscript, or else this task will seem monumental if you leave it to the last minute.

2. Create a spreadsheet to track queries

Keep track of all suitable agents, including their contact details and submission rules. Here’s a ready-made tracking spreadsheet template for you to download. Feel free to modify it as required.

How to Use the Spreadsheet or Set Up Your Own

First, I create four tabs on my spreadsheet. On the first tab, “All,” list all agents who represent your genre. Categorize agents depending on where their details are found, and fill out the info in the corresponding columns.

Columns under the ALL tab

Columns under the ALL tabAgent Name

Agency

Submission URL: I don’t enter submission details into the spreadsheet in case they change. I refer to the live URL when the time comes to query that agent.

Submission email: this might be different from the agent’s normal email address

Policy on querying multiple agents at the agency

Response time

Information of interest: jot down any interesting tidbits along the way

Within each category, prioritize the agents by highlighting them:

Red: agent is a fabulous fit for me

Orange: agent is a good fit for me

Yellow: agent represents my genre

Helpful Hint: Even if an agent is currently closed to queries, still add them to your spreadsheet. By the time you get around to querying, they may be open again.

Your other tabs: red, orange and yellow

Your other tabs: red, orange and yellowNext: Transfer the color-coded agents from the ALL Tab onto their own tabulated sheets (red, orange, yellow). Remove all the color highlights after you do this.

Then: Categorize the agents by their response timeframes. Send out queries in batches of ten, ensuring they have different response times, so that responses will start to roll in at different times.

Then I color code the query rows based on the status; I change the color as new information comes in. These are the colors that I use:

Red: Query sent, awaiting reply

Green: Partial or full request

No color: Still need to send query

Gray: No

I add the following columns of information:

Date first queried

Requested materials sent

Date to follow up

Date to cancel query

Response

If a rejection comes in, highlight the agent gray and immediately send a new query out to another agent. Try to keep ten queries out there at all times. Keep the rejected agents on the spreadsheet so as not to double query them.

Helpful Hint: In the Red, Orange and Yellow categories, pick your top 10 agents who you’d like to query first and place them at the top of the spreadsheets.

3. Create separate email folders

To keep track of all the emails that come and go, create a main folder with subfolders in the email menu so that they don’t clutter up in the sent and in boxes.

Out on submission: for all sent email queries

Full request: to see who is reading fulls

No: move all correspondence for an agent who says no into this folder

Partial request: to see who is reading partials

Helpful Hint: Set a goal of how many agents you plan to query. For example, I have screened and collated 170 world-wide agents on my three color-coded spreadsheets, and I’m not giving up until I’ve queried every single one of them!

Remember, it’s just business

I find that by using a systematic color-coding system to track queries, and by filing my emails, it’s not as disheartening when a query is rejected because I have a call to action in place to immediately send another query out.

Getting into a business frame of mind helps. It’s a bit like keeping a balance sheet: money in—money out. Or submitting bids: you win some—you lose some. My favorite quote from a literary agent on the topic of query rejections is from Janet Reid (aka The Query Shark), on her Rules for Writers guest post on my blog:

.ugb-0a43963 .ugb-blockquote__quote{width:70px !important;height:70px !important}.ugb-0a43963 .ugb-inner-block{text-align:left}.ugb-0a43963.ugb-blockquote{margin-top:47px !important;margin-bottom:-49px !important;padding-bottom:0px !important}I tell you this here to illustrate one more time that when you query agents and you get a form rejection, it’s not always about YOU. It could be about ME.

It’s ME if I’m not enamored of the topic no matter how well written;

It’s ME if I’m overwhelmed with work this week, and just can’t read one more partial;

It’s ME if I’ve got a project very similar to yours and can’t sell it for spit;

It’s ME if I can’t think of an editor who would buy this book and have no idea where to even start;

It’s ME if a colleague handles this genre and I don’t want to encroach on his/her turf.

I don’t tell you any of this, and I don’t apologize for using a form rejection in these cases. I do, and you’ll just have to know that.

Janet’s advice helps me focus on the fact that a query rejection is not personal—it’s just business!

January 21, 2020

How to Write a Killer Villain

Photo credit: Johnson Cameraface on Visual hunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Today’s post is by author and founder of Top Shelf Editing, Christina Kaye (@topshelfedits).

You can’t have a good thriller without a nasty and formidable opponent for your hero. But it isn’t enough to just write a character and call him “the bad guy.” Just as it’s important to create a well-rounded, three-dimensional hero, you must create a villain who is well-developed and not just your standard killer, robber, or kidnapper.

So how can we write a well-developed villain who is a worthy opponent to your protagonist?

Create a backstory

Unless you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi or the like, your villain will also be human. They will have a personality all their own and, in most cases, they’ll have a painful past, so you must tell their story, just as you would with the hero. You want him to be everything that makes us human—fallible, flawed, and complete with a backstory that explains their motives and their reason for being so downright nasty.

First, think about what made your villain turn out the way he did. Why is he killing people? Or why is he so hostile and angry? Most often, the answer comes from an earlier time in his life, prior to our entry into the story. It’s also possible he was born that way—which may not make for a compelling backstory—but usually something happened to him early on that made him snap, even if he already had a tendency to be bad.

Whatever you decide to use as your villain’s backstory, it should be an experience every human can relate to on some level. But somehow, for some reason, Mr. Bad Guy reacted to this tragedy or event in a way most humans would not.

Create motive for his actions

Beyond the backstory, the villain must have a motive for his bad behavior. There must be a “why” aside from “he is a bad guy.” Give your villain a specific motive for why he is kidnapping, robbing, killing, etc. This serves two purposes. One, it gives the bad guy even more character, and two, it gives your protagonist something to follow or a mystery to solve. So create a specific motive for your villain’s actions, and you’ll notice it helps you further develop your plot. Examples of motives for villains include:

Revenge for a prior wrongdoing

Desire to be loved and accepted

To gain notoriety and/or fame

To instill his own sense of justice

Fear of losing his power

Desperation and self-preservation

To achieve/fulfill his destiny

Give him strengths and weaknesses

Just like your protagonist, a villain should have both strengths and weaknesses. His strengths probably keep him from being caught by the hero during the first part of the story. Ideally, his strengths should be a good foil for the protagonist’s weaknesses. Let’s say your hero is a female sleuth and she’s smart and witty, but she has a weakness when it comes to her self-esteem. Have your villain know this and take advantage of it. Perhaps he, as a former cop, leaves her clues and taunts her because she’s not “a real cop.” This allows your villain not only to have strengths, but to use them to his advantage.

Weaknesses should make the villain fumble a few times and ultimately lead to the protagonist putting an end to his reign of terror. Eventually, your hero discovers the weaknesses and turns them against the villain. There must be something that makes the hero able to stop the reign of terror once and for all.

Parting advice

Be careful to avoid overused tropes such as:

Plans to dominate the world

Living in an underground dungeon

A disfigured, gnarly appearance

A tragic childhood story

Obsessed romantically with protagonist

Has a minion or “sidekick” who does his bidding

Villains with these types of storylines are overused, unoriginal, and predictable. Some of these can be used if you find a unique twist.

A complex and complicated villain will be a worthy adversary for your hero to fight and ultimately defeat, and your readers will not only talk about what a crazy, unique villain you created, but they’ll be grateful for your efforts.

Note from Jane: Subscribers to Christina’s email newsletter receive a free self-editing guide.

January 17, 2020

The Complete Guide to Query Letters

This post was originally published in 2014. It is regularly updated with new information. If you’re seeking one-on-one help with queries, I offer a critique service.

The query letter has one purpose, and one purpose only: to seduce the agent or editor into reading or requesting your work. The query letter is so much of a sales piece that it’s quite possible to write one without having written a word of the manuscript. All it requires is a firm grasp of your story premise.

For some writers, the query will represent a completely different way of thinking about their book—because it means thinking about one’s work as a product to be sold. It helps to have some distance from your work to see its salable qualities.

This post focuses on query letters for novels, although the same advice applies to memoirists, because both novelists and memoirists are selling a story. Nonfiction book queries are addressed here.

Before you query

Novelists and most memoirists should have a finished and polished manuscript before they begin querying. However, some may be tempted to begin early because it can take so long to receive responses from agents and publishers. The thinking goes: Well, the agent probably won’t respond any earlier than a month anyway, and I’ll be done by then, so why not get a jump on it?

But what if the agent responds right away?

Or what if you’re not done in a month? What if you realize your manuscript needs a lot more work?

You’ll wish you hadn’t started querying. You may end up rushing your writing or editing process (undesirable to say the least), or admitting to the agent/editor that it will take you X weeks or months to follow up, by which point, their enthusiasm may have waned.

To avoid creating a high-pressure or awkward situation, I recommend you wait until you feel the manuscript is totally done—the best you can make it. That doesn’t mean you have to hire freelance editors or copyeditors or proofreaders, but it does mean fixing or revising anything you know needs attention.

4 elements of every query letter

I recommend your query include these elements, in no particular order (except the closing):

The housekeeping: your book’s genre/category, word count, title/subtitle

The hook: the description of your story and the most critical query element; 100-200 words is sufficient for most works

Bio note: something about yourself, usually 50-100 words

Thank you & closing: about a sentence

I consider personalization or customization of the query optional. More on that later.

In its entirety, the query shouldn’t run more than 1 page, single spaced, if printed, or somewhere around 200 to 400 words. I recommend brevity, especially if you lack confidence. Brevity gets you in less trouble. The more you try to explain, the more you’ll squeeze the life out of your story. So: Get in, get out.

Opening your query letter

Put your best foot forward, or lead with your strongest selling point. Here are the most common ways to begin a query:

Maybe you’ve been vouched for or referred by an existing client or author; mention the referral right away.

If you met the agent/editor at a conference or pitch event, and your material was requested, then put that upfront.

Starting with your story is a classic opening—and my preferred opening—when you don’t necessarily have a good custom or personalized opening for the person you’re querying.

Some queries start in an informational manner, which is also fine: “My [title] is an 80,000-word supernatural romance…”

Published or credentialed writers might start with their successes, especially if they’ve won awards or received an MFA from a well-known school. However, few fiction writers begin their query by talking about themselves because most are unpublished. (This isn’t a problem, though.)

Many writers don’t have referrals or conference meetings to fall back on, so the story becomes the lead for the query letter.

Personalizing the query letter: yes or no?

Your query is a sales tool, and good salespeople try to develop a rapport with their target. It can be helpful to show you’ve done your homework and that you’re not blasting indiscriminately. It can also set you apart from the large majority of writers querying—if it’s done meaningfully.

Here’s an example of a meaningful personalization: “The acknowledgments of The Ideal American mention you with praise, and F. Scott’s masterful work partly inspired my own novel, The Real Deal.“

If you personalize the query by saying, “I found you in Writer’s Market,” or “I see from your website that you’re seeking mystery,” and you add nothing else, that’s not terribly meaningful. Try to say something that can’t be repeated by another writer or used in another query. Here I comment further on whether to personalize your query.

Identifying what you’re selling

Your book’s title, word count, and genre can be stated upfront, although often it’s better to wait until the end of the query to offer this housekeeping information.

Title. Everyone knows your book title is tentative, so you don’t have to explicitly state the title is tentative.

Word count. If your novel’s word count is much higher than 100,000 words, you have a challenge ahead of you. Eighty thousand words is the industry standard for a debut novel. See this post for a definitive list of appropriate word counts by genre. If you have an off-putting word count, some agents recommend withholding this fact until the end of the letter, once you’ve potentially hooked them. Minimum word count for most novels is 50,000 words.

Genre. If you’re unsure of your genre, you can leave out any mention of it. However, if you do, be sure to draw a comparison between your book and another recent title published within the last five years. You can say that your book is written in the same manner or style as another book or author, or that it has a similar tone or theme. Two comparisons are sufficient; the more thoughtful the comparison, the better. Comparing yourself to a current New York Times bestselling author can come across as arrogant or too easy. Instead, demonstrate a nuanced understanding of where your book falls in the literary landscape. Agents and editors will pay closer attention if it appears you are well read, because that increases the chances your book is well written.

Describing your story (the hook)

For most queries, the hook does all of the work in convincing the agent or editor to request your manuscript. Here are a couple formulas that can help you get started.

Who is your main character (protagonist)?

What conflict is she going through?

What are the choices she must make?

What does your character want?

Why does he want it?

What keeps him from getting it?

Here’s an example of a brief hook for The DaVinci Code:

Robert Langdon is an American academic and an expert in the symbols of the ancient world. While on business in Paris, he’s summoned to the scene of a grisly murder in the Louvre where he’s the main suspect. He must race across Europe, one step ahead of the police chasing him, to solve the murder and prove his innocence. In the process, he uncovers arcane messages hidden in the world’s best-known artworks, solves ancient puzzles, and ultimately discovers secrets about Jesus that could bring down the Catholic Church.

As part of this hook, you may need to establish the setting or time period right away; this is especially true for authors of historical fiction or science fiction and fantasy. For example: “My novel, SCI-FI EPIC, is set in the distant future where humans have abandoned earth and now live on the rings of Saturn.”

A good hook balances character and plot. By the end of the query, the reader should have an idea of why we care about the main character(s) but also the story problem or tension that keeps us turning pages.

While the hook formula looks simple—and it is—your story may sound rather boring when it’s boiled down to these elements.

When a hook is well written but boring, it offers the same old formula without distinction. The protagonist feels one-dimensional (or like every other protagonist), the story angle is something we’ve seen too many times.

The best hooks have some kind of twist or an element that helps your work stand out, that makes it uniquely yours. That is: the idea doesn’t feel derivative of existing bestsellers. For example: Every time an agent comes across a query featuring a YA protagonist with special powers acquired on his birthday, and he must figure out how to control these powers at an unfamiliar school, there’s a good chance the agent is going to pass unless there’s a dramatic twist.

How do you know if your idea is tired—by an agent’s standards? Well, this is why everyone tells writers to read and read and read. It builds your knowledge and experience of what’s been done before in your genre, as well as the conventions.

In Laurie Scheer’s The Writer’s Advantage, she well demonstrates the difference between a boring story hook and an exciting one:

I have heard an eternity of pitches featuring women as victims, survivors, single mothers, etc. If someone pitches me a story about a 43-year-old unmarried woman who has had a successful career in advertising or law or pharmaceuticals or whatever, and decides at the last minute that her biological clock’s ticking and she wants to have a child … I will wait for the writer to tell me the rest of the story.

And there is no rest of the story, because in their mind, that is their story.

To which I say, “Who cares?” Seriously, who will care about that storyline? No one. We have seen numerous stories about women wanting to have children later in life. I could produce a list at least two pages long consisting of books and movies with this plot line.

However, if one of the main characters is a 43-year-old single businesswoman having her first child and, at the same time, her 22-year-old niece is also having her first child—because the niece does not see the benefit of having a career and only wants to be supported by a rich husband—I suddenly see some conflict here.

Whenever I teach a class where we critique hooks, just about everyone can point out the hook’s problems and talk about how to improve them. Why? Because when you’re not the writer, you have distance from the work. When you do come across a great novel hook, it feels so natural and easy—like it was effortless to write.

Examples of brief story hooks

Every day, PublishersMarketplace lists book deals that were recently signed at major New York houses. It identifies the title, the author, the publisher/editor who bought the project, and the agent who sold it. It also offers a one-sentence description of the book. These sentences are inevitably well-crafted, and can help you better understand what is currently exciting to agents and publishers.

There are trends and fashions in publishing, and if you were to read the one-sentence description of every novel that sold in your genre in the last six months, you would see definite themes emerge.

While your query hook would get into more detail than the following two examples, these hooks help illustrate how much you can accomplish in just a line or two.

Bridget Boland’s DOULA, an emotionally controversial novel about a doula with a sixth sense [protagonist] who, while following her calling, has to confront a dark and uncertain future when standing trial for the death of her best friend’s baby [protagonist’s problem] [a doula with a sixth sense? cool.]

John Hornor Jacobs’s SOUTHERN GODS, in which a Memphis DJ [protagonist] hires a recent World War II veteran to find a mysterious bluesman whose music [protagonist’s problem] — broadcast at ever-shifting frequencies by a phantom radio station — is said to make living men insane and dead men rise [twist]

Check for red flags in your hook

How to tell if your hook could be improved:

Does your hook run longer than 200 words? You may be going into too much detail.

Does your hook reveal the ending of your book? Only the synopsis should do that.

Does your hook mention more than three characters? Usually you only need to mention the protagonist(s), a romantic interest or sidekick, and the antagonist.

Does your hook get into minor plot points that don’t affect the choices the protagonist makes? Do you really need to mention them?

Does your hook talk about the story, rather than telling the story? Don’t get bogged down in how you wrote the book or what its themes are. Focus on what happens instead.

Writing the bio in your query letter

For novelists, especially unpublished ones, I think it’s OK to leave out the bio if you can’t think of anything worth sharing. But it’s nice to put in something.

The key to every detail in your bio is: Will it be meaningful—or perhaps charming—to the agent/editor? If you can’t confidently answer yes, leave it out. In order of importance, these are the categories of pertinent info.

Publication credits. Be specific about your credits for this to be meaningful. Don’t say you’ve been published “in a variety of journals.” You might as well be unpublished if you don’t want to name them. If you have no fiction writing credits, you don’t need to state that you’re unpublished. That point will be made clear by fact of omission. If you have a long publishing history, just list the ones you’re most proud of or the ones most relevant to what you’re pitching. I don’t recommend including academic or trade journals, since they don’t convey storytelling ability.

Self-published books. Lots of people have self-published, and a self-publishing history doesn’t hurt your chances with a new, fresh project. However, if you’re trying to get an agent or publisher for a book or series that’s already been self-published, my advice is to not bother trying. (If you must, here’s how to pitch an agent with a self-published book.) Do not make the mistake of thinking your self-publishing credits make you somehow more desirable as an author, unless you have incredible sales success, in which case, mention the sales figures of your books and the average star rating.

Your profession. If your career lends you credibility to write a better story, by all means mention it. But don’t go into lengthy detail. Teachers of K-12 who are writing children’s/YA often mention their teaching experience as a credential for writing children’s/YA, but it’s not, so don’t treat it like one in the bio. (Perhaps it goes without saying, but parents should not treat their parent status as a credential to write for children either.)

Writing cred. Mention any writing-related degrees you have, any major professional writing organizations you belong to (e.g., RWA, MWA, SCBWI), and possibly any major events/retreats/workshops you’ve attended to help you develop your career as a writer.

Special research. If your book is the product of some intriguing or unusual research (you spent a year in the Congo), mention it. These unique details can catch the attention of an editor or agent.

Major awards/competitions. Most writers should not mention awards or competitions they’ve won because they are too small to matter. If the award isn’t widely recognizable to the majority of publishing professionals, then the only way to convey the significance of an award is to talk about how many people you beat out. Usually the entry number needs to be in the thousands to impress an agent/editor.

If you have no meaningful publication credits, don’t try to invent any. If you have no professional credentials, no research to mention, no awards to your name—nothing notable at all to share—don’t apologize for it. Perhaps say something brief about yourself—where you live, your education, your day job, hobbies. Remember: Even if you’re unpublished, you’re still completely respectable. You’re mainly getting judged on the story premise, not your bio.

On the other end of the spectrum: Don’t talk about starting to write when you were in second grade. Don’t talk about how much you’ve improved your writing in the last few years. Don’t talk about how much you enjoy returning to writing in your retirement. Just mention a few highlights that prove your seriousness and devotion to the craft of writing. If unsure, leave it out.

If your bio can reveal something of your voice or personality, all the better. While the query isn’t the place to digress or mention irrelevant info, there’s something to be said for expressing something about yourself that gives insight into the kind of author you are—that ineffable you. Charm helps.

Novel queries don’t have to address market concerns

Don’t be tempted to elaborate on the audience or market for your novel. This is often misunderstood since nonfiction writers do have to talk about market concerns. However, when it comes to selling fiction, you don’t talk about the trends in the market, or about the target audience. You sell the story. I often encourage memoirists to follow the same principle and leave out readership information—save it for the book proposal if it’s requested.

Also, novelists don’t need to discuss their marketing plan or platform. Sometimes you might mention your website or blog, especially if you feel confident about its presentation. The truth is the agent/editor is going to Google you anyway, and find your website/blog whether you mention it or not (unless you’re writing under a different name).

While having an online presence helps show you’ll likely be a good marketer and promoter of your work—especially if you have a sizable readership already—it doesn’t say anything about your ability to write a great story. That said, if you have 100,000+ fans/readers on Wattpad or at your blog, that should be in your query letter.

Close your letter professionally

You don’t read much advice about how to close a query letter, perhaps because there’s not much to it, right? You say thanks and sign your name. But here’s how to leave a good final impression.

You don’t have to state that you are simultaneously querying unless the guidelines demand it. Everyone assumes your query is being sent to multiple parties and not to a single person at a time. I do not recommend exclusive queries.

If your manuscript is under consideration at another agency, then mention it if/when the next agent requests to see your manuscript.

If you have a series in mind, this is a good time to mention it. But don’t belabor the point; it should take a sentence, e.g., “This is the first in a planned series.”

Resist the temptation to editorialize. This is where you proclaim how much the agent will love the work, or how exciting it is, or how it’s going to be a bestseller if only someone would give it a chance, or how much your kids enjoy it, or how much the world needs this work. Basically, avoid directly commenting on the quality of your work (whether that’s to flatter or criticize yourself). Your query should show what a good writer you are, rather than you telling or emphasizing what a good writer you are.

Thank the agent, but don’t carry on unnecessarily, or be incredibly subservient—or beg. (“I know you’re very busy and I would be forever indebted and grateful if you would just look at a few pages.”)

There’s no need to go into great detail about when and how you’re available. At the bottom of your letter, include your email address and phone number.

Do not introduce the idea of an in-person meeting. Do not say you’ll be visiting their city soon, and ask if they’d like to meet for coffee. The only possible exception to this is if you know you’ll hear them speak at an upcoming conference—but don’t ask for a meeting. Just say you look forward to hearing them speak. Use the conference’s official channels to set up an appointment if available.

The following stuff doesn’t belong in the query

Your many years of effort and dedication

How much your family and friends love your work

How many times you’ve been rejected or close accepts

How much money you’ve invested in editors or editing

Quotes of praise from anyone, or mentioning how such-and-such well-known person has read your work and/or offered advice on it. Perhaps it’s boosted your ego or confidence that some VIP has read your work or offered a critique. But agents/editors will make up their own mind, and if your VIP really believed in your work, why aren’t they offering you a referral to their agent or editor?

The submissions strategy I recommend

If you’d like to take a conservative approach, divide your agents into buckets: A list, B list, and everyone-else list. Try submitting in rounds of 4-8 at a time (depending on the size of your list), including 1-2 of each agent type. If your A list people immediately and favorably respond, then I’d send out another round right away, a mix of As and Bs, to see if you can gin up competing interest. If responses trickle in with no particular pattern or order, send another round within 2-4 weeks or so. At least every month, send another round until your list is exhausted.

If you immediately see a pattern in the response that indicates something’s amiss, you can adjust your approach for the next round of queries. The reason I recommend this conservative approach is it tends to be easier to manage psychologically. But there’s nothing wrong with sending out your materials to everyone on your list at once. It just means that you don’t get that “next chance” or opportunity to adjust your pitch later. (Once a rejection, always a rejection—or that should be your assumption.)

Query letter example for a novel

Special advice on email queries

Special advice on email queriesEmail and digitally submitted queries tend to get read and rejected more quickly than snail mail queries; with that in mind, you may want to create two separate versions of your query letter, one for email and another for printing. Here’s a formatting process I recommend:

Write your query in Word or TextEdit. Strip out all formatting. (Usually there is an option under “Save As” that will allow you to save as simple text.)

Send the query without any formatting and without any indents (block style).

Don’t use address, date headers, or contact information at the beginning of the e-mail; put all of that stuff at the bottom, underneath your name.

The first line should read: “Dear [Agent Name]:”

Some writers structure their e-queries differently than paper queries—they make them shorter or add more paragraph breaks. Usually the hook should go first, unless you have a strong personalization angle.

If you have an e-mail address for an editor/agent who doesn’t accept e-mail queries, you can try sending your query on a hope and a prayer, but you probably won’t receive a response. In fact, I’ve heard many writers complain that they never receive a response from email queries. (Sometimes silence is the new rejection.) This is a phenomenon that must be regrettably accepted. Send one follow-up to inquire, but don’t keep sending e-mails to figure out if your e-query was received.

You’ve sent your query—now what?

If you don’t hear back, follow up after the stated response time using the same method as the original query. If no response time is given, wait about 1 month. If querying via snail mail, include another copy of the query. If you still don’t hear back after one follow-up attempt, assume it’s a rejection, and move on. Do not phone or visit.

If an agent asks for an exclusive read on your manuscript, that means no one else can read the manuscript while they’re considering it. I don’t recommend granting an exclusive unless it’s for a very short period (maybe 2 weeks).

In non-exclusive situations (which should be most situations): If you have a second request for the manuscript before you hear back from the first agent, then as a courtesy, let the second agent know it’s also under consideration elsewhere (though you needn’t say with whom). If the second agent offers you representation first, go back to the first agent and let her know you’ve been made an offer, and give her a chance to respond.

Additional resources on query letters

QueryShark: run by an agent who critiques queries

AgentQuery: a database of agents, plus a community that can help critique your letter

Looking for more?

Start Here: How to Get Your Book Published

Start Here: How to Write a Book Proposal

Back to Basics: Writing a Novel Synopsis

Need one-on-one help?

Check out my Query Letter Critique Service.

Copy Write Consultants offers agent and publisher research assistance.

January 16, 2020

How to Choose an Agent Amid Competing Offers

Photo credit: derekbruff on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC

Today’s post is an excerpt from Funny You Should Ask by literary agent Barbara Poelle (@Bpoelle), a new book collecting questions and answers from her popular column at Writer’s Digest.

Dear FYSA,

I received an offer of representation for my young adult novel. When I notified the other agents who had the full manuscript that I was withdrawing from consideration, I got an additional five offers! What would you advise I ask of the offering agents in this situation?

Sincerely,

Full Dance Card

Dear Happy Dancer,

Well, first of all, if I am one of the offering agents, I advise you to pick me. I am delightful.

But really, thank you so much for this question, because this happens more often than most authors realize. When multiple agents make an offer on the same manuscript, there are indeed several questions you should ask the offering parties, and yourself, in order to determine which one might be your best match.

I should note for others here that these questions should also be considered even if only one agent is offering. After all, an offer isn’t an obligation—it’s an invitation, right? So invite them into a conversation!

First, let’s assume that each of the offering agents is someone you chose for a particular reason, and not merely the result of a shot of tequila and a handful of darts flung at the pages of the Guide to Literary Agents. I would suggest taking a page out of my client Traci Chee’s approach when the same thing happened to her—open a new document on your computer or grab a legal pad and write every agent’s name and the primary reason why you queried each one at the top.

Next, take a look at how long each agent has been in practice and how many clients he represents. We’ll call the resulting comparison bandwidth versus experience. A newer agent with only a few years under his belt may have a greater bandwidth for more personal attention and editorial work, while an agent with a robust and lengthy client list has the reputation that accompanies years of experience to guide your career. Which is more important to you? (Hint: There is not a wrong answer here.)