Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 86

January 10, 2020

5 Common Story Openings to Avoid—If You Can Help It

Note from Jane: The following advice is from me, but I’m also hosting a 1-hour online class taught by former literary agent Mary Kole on how to craft irresistible first pages. Learn more and register.

For unknown and unpublished writers, a lot rides on your story opening because it’s the first impression you make. If it’s a lackluster impression, an agent or editor will rarely wait to see if things improve. Rather, they’ll just move on to the next submission in the hopes that it’s good from page one.

Here are the most common and lackluster story openings I see when reviewing clients’ work. While it’s not wrong to open in these ways—and a great writer can make even the most pedestrian series of events read as fascinating—consider if you can find a more advantageous way to begin.

1. The waking up scene

This is where we meet the character waking up in bed, then perhaps getting ready for school or work. Maybe they’ve woken up because the sun is shining through the window, or maybe they receive a phone call or text. In the case of young adult fiction, a nagging parental figure is frequently seen. It doesn’t really matter how or why they wake up—only that it’s a waking up scene.

Perhaps it’s a very important day for the character and that’s why we’re seeing it from the very first minute. Or perhaps you want to establish the character’s everyday world or routine—then disrupt it.

But morning routines and literal wake-up calls rarely make for great reading. They put a lot of pressure on the writer to have a compelling point-of-view character or literary style—to give the story life, charm, or tension that keeps us reading.

If it is in fact a very important day—one the character has been waiting for—how about starting the story during or after the big thing that will occur? That can help with not just tension, but story pacing.

If you start with an important call or text, does it really need to be dramatized (shown) on the page? Maybe it does. Make sure you’re not starting there by accident or because it was the first idea that came to you.

2. The transit scene

Ideally, we want an opening situation that presents tension—a character who’s not getting what he wants or meets opposition, or that seeds a larger story problem that will emerge and develop.

Transit scenes—describing characters moving from point A to point B—often lack this. Or if there is tension, it’s one that we’re all too familiar with. Traffic. Bad subway companions. Mundane annoyances of life.

In other words, it has a little too much in common with what agents or editors experienced that morning. Transit can make for a slow and ordinary beginning unless something quite odd is going on or we have an entertaining voice.

However, transit scenes can be tempting if the character is embarking on a big and wild trip or heading to some important event. Or they might help establish an unusual setting or world.

Consider: is the pacing brisk enough in your transit scene? Is enough happening, or are you using it as a way to establish back story (see #3 below). Will an agent/editor get impatient with the amount of detail you’re including? Think through every line: Why is this description here? What purpose does it serve for the larger story problem or characterization? Is it needed at this moment?

Sometimes writers are told to “show don’t tell” so often that they show absolutely everything—they slow down every moment, and go over every bit of the setting—without regard for how the detail or perspective might serve the forward-moving story.

3. The rocking chair scene

This can be a cousin to the transit and waking up scene. It’s when your character is typically sitting alone and contemplating life—whether recent events or their entire history—just thinking, thinking, thinking, perhaps with some commentary on the scenery. This might serve to establish the character and give readers the back story needed (in the author’s mind, at least) to understand what’s ahead.

If this sounds like your opening, count how many pages it takes before someone else enters the picture. Rather than having the character think about someone else, can you put them into a scene with that person? Can the character think about past events for a line or two while also engaged in an activity relevant to the forward-moving story?

Extended internal monologue in the opening usually only serves one purpose: to deliver back story to the reader. See if you can convey that back story in a more evocative or interesting way, and parcel it over a series of chapters. The more you can begin with the character engaging with the world rather than reflecting on it, often the better position you will be in from a submissions perspective. It’s of course possible to have a successful reflective opening, but it’s far more difficult to pull off and tends to rely on the author’s command of voice.

4. The crisis scene

If we meet a character who is in crisis or pain from line one, we have something tension-filled on the surface, but it may not raise any interesting questions or reasons to keep reading if there’s not sufficient context. In some openings like this, we don’t even get the character’s name—just the fact they’re in wrenching agony.

Such openings tend to emphasize physical, bodily description, and showing, not telling. They might deliberately avoid identifying characteristics and try to increase tension by making us wonder what’s going on. However, this can be false suspense. This tends to be especially true of vague chase scenes where an unknown character is under extreme duress, but we don’t know why, or who/what the threat is.

While it can be to a writer’s advantage to begin with action, don’t forget the opening also introduces us to character. For a story to take shape, we need to see what’s happening through their distinctive viewpoint. As Peter Selgin says, “No point of view = no story.”

Note that pain in this case could be physical pain or psychological pain. Focusing on a character’s intense grief in the opening can be a risk if the reader lacks insight or context as to how this grief is unusual or important to this particular story.

5. The dream sequence

I often see dream sequences combined with crisis moments: a character is suffering in some way, then at the end of the first chapter, they wake up and it’s a dream. A prophetic dream, usually—it’s an ominous sign of what’s ahead, used as foreshadowing.

This is a common trope and a tired one. Just about anything else would be better unless you’ve found an amazing new way to frame it.

Final advice

Whether you ought to change your opening and revise is never an easy call. Pulling on one strand of a story to fix something possibly minor can unravel the entire thing or introduce new problems. If you receive a pattern of feedback that amounts to the same advice, though, you should strongly consider a revision.

Keep in mind that after the first five or ten pages are another five pages, and another. If challenges exist in the opening, that might indicate other challenges down the line—which is why agents and editors use them as an indicator of overall manuscript quality.

Note from Jane: This post was written by me, but I’m also hosting a 1-hour online class taught by former literary agent Mary Kole on how to craft irresistible first pages. Learn more and register.

January 7, 2020

What Does It Mean to Be A Full-Time Author?

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

A few years ago, I wrote a blog post for my website called Why Writing is a Full-Time Job—Especially if You Don’t Have a Book Deal. In an effort to better advise my clients, I discovered that some of the challenges I was facing as a freelance editor were very similar to those of unpublished writers. For example, I’d noticed that people with corporate jobs tended not to take our work seriously, as our earnings weren’t on par with theirs.

Established or not, most of us in creative fields put in as many hours as those with traditional day jobs—probably more—but how should these hours be spent? How should writers’ daily responsibilities change as their careers gain momentum? And what if their return on investment is low, or it leads to extreme but short-lived financial success, as it did for this writer?

I asked literary agents Jim McCarthy of Dystel, Goderich & Bourret and Paula Munier of Talcott Notch Literary these and other similar questions. As with all my Q&As, neither knew the other’s identity until after they submitted their answers.

Sangeeta Mehta: Given the demanding nature of this work, even the most prolific published writers usually spend only a few hours a day actually writing, though they might allot additional hours to writing-related projects. For full-time writers who are as of yet unpublished, what should be the priority other than writing and revising? Reading inside and outside their genre? Building a writing community? Creating a website?

Jim McCarthy: I hope it doesn’t sound hokey, but I actually mean this very deeply: the best thing you can do to help your writing career is keep writing. Yes, it can be helpful to have a big social media following. And networking with other writers can prove incredibly useful when you’re looking for blurbs or for people to help spread the word. It can pay off to establish connections with your local booksellers. It’s always a good idea to have a website. But those are truly extraneous compared to the act of writing.

Paula Munier: The most important work of a writer is to write and rewrite. But when you have an eye to getting published, there are certain things you need to do. You need to read widely in your category, you need to know your genre well, and you need to be able to talk about your work within the context of that genre.

Writing to sell means understanding the marketplace, your genre and where your book fits in that genre. It means understanding your competition and how you can position your work against that competition. It means befriending writers of all kinds.

You’ll pay it forward when it’s your turn. But in the meantime, you make friends with those writers who are at your level and beyond so that you can get to know not only what it means to be a writer, but what it means to be an author.

Yes, you should have a website and do social media, but that should be part of your being part of the writing community. Join your genre association, participate in your local writers’ groups, attend book signings and other publishing events.

This way, when you are ready to shop your work, you’re more likely to be shopping a project that not only succeeds on a craft level, but one that has a chance of succeeding in the marketplace.

How should writers’ work differ once they have a book deal in place? Once their book is published? For example, should they focus on attending writing festivals? Doing interviews? Providing endorsements for other writers? How much of a say does the writer have in this decision, as opposed to their agent or publisher?

JM: The writer definitely has a say. They will be involved in helping to choose their delivery dates. The more successful your books are, the more demands will be made of your time. It becomes increasingly important to be aware of your limits and be comfortable giving voice to those limits rather than striving for unachievable goals. If you become a bestselling author, it’s more likely that you’ll be asked to travel and give talks and work with book clubs and give blurbs. The most important thing becomes your ability to prioritize what is most important to you and your work. What changes most is that things that sound like a lot of fun (which often ARE a lot of fun) can become a drain when they’re part of an aggressive schedule.

PM: Once you have a book deal in place, your first order of business is to follow your editor’s suggestions to make that book as good as it can be before it hits the marketplace. Then your job is to decide along with the help of your marketing and publicity team—whether that’s your own or that of the publisher—who your audience is. That is, who is most likely to buy your book? Which readers of which books by which authors already out there succeeding in the marketplace could be counted on to buy your book as well?

Once you figure out who your audience is, you have to figure out where those readers are and how to connect with them. Are they online? Browsing bookstores? Attending festivals? This is where knowledge of your genre and writing community comes in.

In the old days, you had to rely on your publisher to do the sales and marketing and publicity. Today you don’t have to rely on your publisher, but there’s an expectation and even an obligation for you to do that on your own. So, you have to decide where to spend your time and money and effort: What kinds of marketing and publicity appeal to you? Social media? Lectures? Events? Which will drive readers to your books? Which are going to actually boost sales?

Ask yourself 1) what you’re most comfortable with and 2) what’s most productive in terms of both reaching your audience and fueling sales, and then find a happy marriage between the two that works for you.

When considering new clients, are you sometimes leery of writers with strenuous day jobs who might not have time to make the revisions you recommend? Writers who are unlikely to have flexibility at the pre- and post-publication stage, when publicity must be factored into their schedule? How do you distinguish potential clients’ enthusiasm for being published from their ability to commit to this endeavor?

JM: I give everyone the same benefit of the doubt. I have clients who have become successful enough that they’ve left demanding jobs behind. Or miraculously balanced an intense workload. I also have clients who write full time who can’t make a deadline. I don’t really believe it’s possible to know how someone will be about working on deadline until they’re already there. If there is some magical question to ask that would reveal the answer, I haven’t found it yet, so this isn’t a consideration as much as it is something I keep an eye on as our work together moves forward.

PM: Most people have demanding day jobs, whether they’re raising kids at home or running companies outside the publishing sphere. The majority of my clients have demanding day jobs—doctors, lawyers, educators, scientists among them. I don’t think that matters, because it seems to me that that old adage if you want something done, give it to a busy person holds true.

What I really look for is writers who are ready to become authors. Writing is a solitary endeavor, but being an author is a very public endeavor. It requires a willingness to go to events, a willingness to do social media, a willingness to get the word out about your book in any and every way possible.

I do meet writers who tell me, “I just want to write books. I don’t want to have anything to do with selling them.” Those are not people I can work with. I need people who are going to commit to being authors as well as writers, people who want to be career authors in this for the long haul.

On this same note, should writers be apprehensive of agents with side jobs, whether within a literary agency (selling rights or managing royalties) or outside the publishing field? If an agent is running an editing business for extra income, or they have their own book contract to fulfill, could this be a conflict of interest? Detract from the agent’s ability to represent and advocate for their clients?

JM: As someone who was able to start agenting only because I had a salaried position at the agency working on financial and royalty management, I don’t think there’s any reason to avoid someone specifically because they have another role at their agency. My colleagues who continue to balance their salaried positions and their client lists are some of the best agents I know.

On the other hand, having a job outside of their agency but within publishing? That’s tricky. Anyone who is charging to edit while also looking for clients has a conflict of interest in my mind unless they make it extremely clear that they will not consider anyone that they edit for representation.

As far as agents who are also authors? I have never understood how they do it, but some brilliant agents have published books and managed the workload seemingly without conflict. A tip of the hat to them for managing what must be an incredibly brutal schedule.

PM: Full disclosure: I’m an agent and an author. I’ve been a published writer since college, and I was also an acquisitions editor for many years. I think all that experience benefits my clients. In this era of declining advances where making a living as a writer is even harder than it used to be, making a living as an agent is even harder than it used to be, too. That’s why many agents have more than one income stream, just as many small business owners (not to mention many writers) do. I wouldn’t hold that against them. What’s most important is that you work with an agent who has a solid plan for the marketing of your work and has a track record executing such plans successfully.

When talking with an agent, consider these questions: Is this agent enthusiastic about your current project? Does this agent sell in your genre? Does this agent have the relationships with the editors who buy projects in your genre? Does this agent understand and support your career goals? These are the questions you have to ask yourself.

Conventional wisdom holds that writers should never quit their day job until their royalties exceed their salary. But given the demands involved in being a writer, including self-promotion, is there a point at which they should reduce their hours or take a leave of absence? For those who aren’t in a position to compromise their current job, would you recommend hiring an author assistant to help them with social media, for instance? Or an independent marketing firm to work with the publisher’s marketing department?

JM: Conventional wisdom is right. Publishing is too volatile an industry to depend on long term for your income until you already know that projected money is GUARANTEED to be enough to support you for at least two to three years. If you don’t have a job and can give all your time to publishing? Great. But that shouldn’t be the standard or the expectation. Writing shouldn’t only be for people who have supportive partners who can carry them financially. It might be slower or more challenging to get books finished if you’re holding down a separate job, but there is zero shame in having to work full time to support yourself while you write. And again, I agree that self-promotion is important, but it’s not the make-or-break that some people make it out to be.

PM: I would never advise anyone to quit their day job. That’s a personal decision, and even if you get a six-figure deal, when you run the numbers it’s not as much money as you think (see the blog post I wrote about this). And you may or may not earn out that advance.

Only you can decide how much time you can spend writing, how much time you need to spend marketing and doing social media and going to events and all those kinds of things. Once you get a sense of what you’re good at, what actually works and sells books and where your time and effort and energy is best spent, then you can decide how to allocate your resources. It’s expected that you’ll spend some of your advance on marketing and publicity—and those expenses can add up fast.

I have clients who’ve hired publicists to do marketing campaigns for them around the launch of their book and hired social media managers and used outside book marketers to do special mailings to libraries and independent bookstores. I have clients who’ve run BookBub promotions and gone on blog tours and started newsletters and done keyword search and on and on. There are all kinds of ways to market books. You have to decide where your resources are best spent. The upshot is that there are all these options.

According to this Twitter thread, writing should be treated like a small business, and it generally takes five to ten years to get a small business off the ground. But most small businesses are forced to shut down if they don’t turn a profit within this time period. Does this same thinking apply to writers? Can writers who invest money into their writing career—in the form of MFA programs, conferences, workshops, etc.—expect to recoup it, either directly or indirectly?

JM: Yes, writing is a business. But is everyone looking at a 5-10 year window to profit? No. That’s an impossible construct for most authors. You have to have a clear idea of what your goals are—how often you want to publish, what you can and should expect financially, and how much time you need to know you have available to you, but I don’t want writers to feel like they have to have it all figured out ahead of time. Or that there isn’t room for people who don’t have enough time to invest five years in their project.

I also am very wary of anyone investing money in their career. Is an MFA worth it? Financially, probably not. But if you have the capital to get one and want to hone your craft, then by all means, go for it. I haven’t really seen any for-hire publicists achieving particularly notable results for authors who aren’t already bestsellers. But I have seen them charge a fortune. I’m skeptical of almost all cost-based “help” in a writer’s career.

PM: I think it’s absolutely true that being a writer is like running a small business, but it’s like running a small business as an artist. Writers are artists, and most artists don’t make a lot of money. That’s just the nature of the arts.

That said, you have to find a way to continue to improve your craft, and that means doing whatever you need to do to take your work to the next level. When I was very young and joined my first writer’s group, the most impressive published writer in the group was an older woman who looked me up and down and said, “It takes a million words to make a writer.” And I sat there doing the math in my head, thinking, Oh God, I have 950,000 words to go. And so I did.

Honestly, expecting that you can attain the level of craft necessary to publish without taking any classes or investing any time, energy, and money into the resources you need to make your work the best it can be is really naive. If you decided to take up watercolor painting, you would take a watercolor class and you would not expect your first watercolor to sell at a gallery or hang at The Met.

There is a level of craftsmanship you have to acquire before you’re ready to be traditionally published, and that means an investment on your part. I’m looking for writers who are willing to make that investment.

It’s not a secret that many people who write full-time—but don’t earn a living from their writing—are financially secure, if not well-to-do. What can the book publishing industry do to elevate those who lack such socio-economic privilege? Create more grants and fellowships? Provide more mentorships? Can you think of any strides the industry has already taken that you’re particularly proud of?

JM: The entire publishing industry focuses in a way that benefits the most financially well-off individuals. I would love to see publishers invest more in grants, scholarships, and mentorships. The most difficult aspect of that is how slim the profit margins are industry-wide. I wish I had a wonderful answer to this. I wish I knew how to raise book prices, get more of the money to authors, and not cause lower sales or damage the ability of libraries to purchase widely.

In terms of what does exist, know that applying for grants is time consuming and requires resources, but they’re out there.

We Need Diverse Books offers the Walter Grant “to provide financial support to promising diverse writers who are currently unpublished.”

Lambda Literary has a resource page for writers looking for grants specific to queer writers.

On a more macro level, there are grants from Arizona Artist Research for state residents, and Kansas City has them for city residents.

I think it’s worthwhile to spend a bit of time googling grants that you may be eligible for and remembering to look for ones based on something as broad as what genre you write in and as specific as where you live.

PM: This is an interesting question. I’m not sure I know enough about it to answer it properly or thoroughly. I can tell you that the writers I meet, the aspiring writers who have yet to publish, come from all kinds of backgrounds and all socioeconomic levels. What they have in common is a love of books and a love of reading and a determination to tell their stories.

Most conferences offer scholarships. Most genre associations have scholarships and grants available to writers as well. It’s important that we hear as many voices as possible. I applaud, for example, Crime Writers of Color and I applaud publishers like Jason Pinter and his new imprint. These are moves in the right direction. But we can always do more to help talented writers get published.

That’s what we agents do for a living. We devote our lives to championing our client’s work—and we don’t get paid until we do. Getting an agent isn’t easy, and each agent can only take on so many clients. I wrote three books on writing because I can’t be everybody’s agent, but at least I can share what I’ve learned along the way.

With all the financial uncertainties that come with the writing life, do you still find yourself encouraging writers to follow their dream and never give up, as the expression goes? How do you reassure those who feel they are investing more into their writing than they are receiving in return?

JM: I absolutely recommend that writers pursue their dreams. But I want people to pursue them responsibly. Having it be a goal that you want to write full time is fantastic, but you need to make sure you can support yourself before you do that. And if you have lean years (as 99.9% of authors do), you should be prepared for that, whatever that means for you—whether having savings you can eat into, other work you can return to temporarily, a partner who can support you. Chase your dreams by all means. Keep trying, and remember that every author has been rejected, and that is just part of the process. But remain clear-eyed about financial realities.

PM: Writing is a calling. It’s a commitment. It’s a practice. Writing is something you do for the love of it, for the want of it, for the need of it. If you’re writing because you want to make money or you want to be on TV or you want to be a “rich and famous writer,” or for any reason other than the absolute commitment to it, then you’re in the wrong business. If you want to make money, you should go be an investment banker.

Which is not to say that you can’t make it—and make it big. As an agent, I’m looking for the next Lee Child or the next Lisa Gardner or the next Stephen King or the next Margaret Atwood. Somebody has to be, and it may as well be you.

That’s what I tell all my clients.

Because I’m living proof. I’ve secretly wanted to be a mystery writer since I read my first Nancy Drew novel as a kid. Fast forward decades later when I’m a grandmother, for goodness’ sake, and I finally publish my first mystery.

I’d given up on that dream, but I’m living it now.

Anything I can do, you can do better.

Jim McCarthy (@jimmccarthy528) is a vice president at Dystel, Goderich & Bourret, where he’s been for his entire 20-year career. He represents adult, young adult, and middle grade, both literary and commercial, and is particularly interested in literary fiction, underrepresented voices, fantasy, mysteries, romance, anything unusual or unexpected, and any book that makes him cry or laugh out loud.

Paula Munier (@PaulaSMunier) is the Senior Literary Agent and Content Strategist for Talcott Notch Literary, where she specializes in high-concept commercial fiction—especially crime fiction and book club fiction—as well as nonfiction. A long-time writer and former acquisitions editor, she’s the USA TODAY bestselling author of the Mercy Carr series from Minotaur. A Borrowing of Bones, the first in the series, was nominated for the Mary Higgins Clark Award. Booklist called the second, Blind Search, a “not to be missed K9 mystery” in a starred review. A writing teacher and yoga instructor, she’s written three popular books on writing: Plot Perfect, Writing with Quiet Hands, and The Writer’s Guide to Beginnings, as well as the acclaimed memoir Fixing Freddie and Happier Every Day: Simple ways to bring more peace, contentment and joy into your life.

January 6, 2020

What Your Choice of Dialogue Tags Says About You

Photo credit: Marc Wathieu on Visual Hunt / CC BY-NC

Today’s post is by editor Christopher Hoffmann from Copy Write Consultants (@CWCauthorassist).

There are so many moving parts an author needs to pay attention to when writing fiction—POV, character development, narrative structure, happy-hour specials—that it’s easy to miss the small stuff, the things that we think we instinctively understand and already do very well.

How dialogue is set off from the rest of the narrative is one of those little things that makes a big difference in how your story reads and what the reader understands about you, including:

Are you a Serious Author, an author of genre fiction, or a clueless dilettante?

In the everyday speech of most people, we really only use a couple of dialogue tags when discussing direct discourse: said and like. Said is used by almost everyone; like is largely limited to people who were born after 1970 (or 1965, or maybe 1960; this isn’t an exercise in linguistic demography).

“Then the judge said to me, ‘You are hereby remanded to state custody for a term of no less than ninety days for the egregious overuse of the words fraught and curated.’ And I was all like, ‘How can I possibly keep my self-help-slash-boutique-spice blog going without those words?’”

But the written word allows us the use of many, many more dialogue tags: exclaimed, answered, yelled, spoke, stated, replied, questioned, shouted, gibbered, opined, etc. (Just to be clear, spoken language allows this as well, we just rarely avail ourselves of them when reporting speech verbally.)

So how do we decide which words to use where? And more importantly, which words not to use, maybe ever?

Said and Only Said (or Asked)

One way to look at it is to consider any movement away from the exclusive use of said or asked a step away from the very “best” writing, from the kind of writing intended to be considered “literary.” If you spend any small amount of time examining blogs or books on writing, you will find that this is a very common directive: use said, asked, and nothing else.

There are a number of reasons for this, but the most common works in conjunction with that other famous maxim: show, don’t tell. If you use the word ranted to describe the speech act of one of your characters, you’re telling your readers how to understand what is happening rather than illustrating through action and dialogue.

The young man stared wild-eyed at the judge. “My blog is the only thing that keeps the demons at bay! How am I going to sell my homemade anchovy bitters now?” he ranted.

Rant means to talk excitedly and vehemently; from the perspective of many literary prescriptivists you should already be giving your reader enough information that she understands this dialogue as ranting without needing it to be colored in for her.

On the other side of things, certain dialogue tags are simply redundant:

Looking the defendant over, the judge opined, “Fish never belongs in a cocktail, young man, and moreover, I find the ensemble you’ve worn to court today to be overly modish and without regard to classic sartorial conventions.”

The reader doesn’t need to be told that the judge opined, as his statement constitutes an opinion and not fact—fish would obviously go well in a cocktail! I mean, if wormwood is really what makes absinthe special to some folks, I don’t see why the je ne sais quoi of a killer Caesar salad shouldn’t be the same for a fantastic tipple. Not that I’m going to try it.

All of which is to say that if you aspire to the more literary side of writing, consider very carefully when using dialogue tags other than said or asked.

Other Words Can Be OK, Too

But what if your main goal is to produce something well-written, entertaining, and, well, maybe even unabashedly commercial? Luckily for you, the conventions of commercial and genre fiction are much more forgiving.

While opined in the example above might be considered to be redundant or unnecessary by some, in other contexts it might be interpreted rather as giving early color to a bit of dialogue. The reader gets a sense of what is coming before it arrives. It also gives away the perspective of the narrator, something that may be very desirable—this also applies to the example using ranted. Consider:

“When I get out of here, I’m going to come after you, and you’re going to wish you’d never heard of organic oregano,” he said.

The reader needs to rely on context and the content of the speech to form an opinion about what is being said. On the other hand:

“When I get out of here, I’m going to come after you, and you’re going to wish you’d never heard of organic oregano,” he ranted.

Here, the narrator is telling the reader what she thinks about what the young man is saying. Depending on the POV you’ve chosen, this can profoundly affect how the reader interprets what is happening. (For more on POV and how it affects narrative, check out other excellent posts on Jane’s blog, here and here.)

If you choose to use tags other than said and asked, it’s still a good idea to limit these; think of them as dashes of hot sauce—a few can be tasty, but too many ruin a dish.

Some Outliers

There is another subset of dialogue tags that are often disapproved of outside particular genres of fiction, sniffed at and side-eyed by many authors and critics. These include breathed, sighed, and snarled, among others.

Purists will point out that these words do not denote speech acts; one may quibble with the use of rant, but it at least describes a way of speaking. However, there are contexts in which the use of this kind of dialogue tag is accepted and appreciated.

In romance novels, for instance, these tags often find a home because they make the dialogue bodily; they can sensualize dialogue in a way that the words don’t necessarily suggest by associating them with the physicality of the speaker.

As she handcuffed him, the bailiff breathed, “I love organic oregano.”

“I wish I could share some with you,” he sighed.

Given the young man’s outburst in the earlier example, if said was used here instead of breathed, one might interpret the bailiff’s words as sarcasm; instead the reader senses that the words were said softly, perhaps close to the young man’s ear, and represent warm feelings on the bailiff’s part. Likewise, while sigh is not a speech act either, we all have sighed while talking and recognize the bodily actions as simultaneous.

As with other non-said/asked dialogue tags, these should be used sparingly.

For Clueless Dilettantes Only

Finally, some words exert an irresistible pull on novice writers and even those more experienced who have simply been paying too much attention to happy-hour specials. These words are made to function as dialogue tags, but they are incoherent—the usage is forced and the result comes across as amateurish. These include smiled, laughed, sneered, frowned, and hissed (as well as so many others I’ve tried to forget).

“I know that relationships among cellmates can be awfully fraught, but I’d like for us to get things off to a good start,” smiled the young man to the burly convict standing in front of his bunk.

What can it possibly mean to “smile” words to someone? How could one “sneer” something? These don’t add meaning in the way breathe and its compatriots can—they are merely shortcuts that when examined closely prove nonsensical. Save your editor time and yourself money by avoiding these at all costs. The money you save can be used at happy hour.

December 31, 2019

My Must-Have Digital Media Tools: 2020 Edition

Note from Jane: On Jan. 2 at 1 p.m. EST, I’m offering a free, one-hour session to discuss these tools and more. Register here.

Every year, I update this post with tools that have indispensable to my business, productivity, and well-being. Here’s my 2020 list. I have not been paid to recommend any of these services or products, although you will find an affiliate link or two (always disclosed next to the link).

1. Zoom

Zoom is my go-to online meeting service that I find exceptionally reliable; it’s like Skype, only better. I use it for client meetings, personal chats, online courses, and even to pipe in guest speakers for in-person events. It can record all meetings; once the meeting ends, the resulting file is downloaded locally or stored in the cloud (or both). I’ve found it nearly foolproof since participants can join on any device (including a phone), use video, or stick with audio only. Find out more about Zoom (note: this is an affiliate link). You’ll find both free and paid plans.

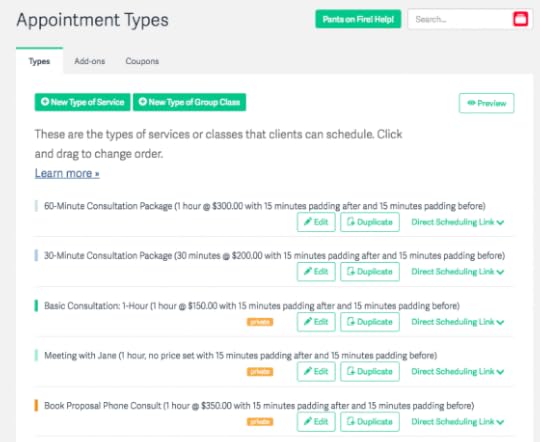

2. Acuity Scheduling

For several years, I’ve used Acuity + Zoom to streamline my client meetings and scheduling. Acuity is a full-featured appointment and scheduling service that allows anyone to book free or paid appointments with you. No more back-and-forth emailing to set up appointment times, and it hooks into availability on your Google calendar (among others). Acuity can be embedded into your site or shared as a link.

Acuity is free to start but you’ll have to pay at least $15/month for the best or most powerful features. Note: This too is an affiliate link, but I wouldn’t recommend them if I weren’t 100% happy with the service.

3. Gravity Forms + Stripe for payments

Since I primarily sell services from my site and not products, I don’t need a shopping cart or fully featured e-commerce solution such as WooCommerce. Instead, I use the premium plugin, Gravity Forms and use Stripe to process credit card payments. This allows people to buy specific service packages by completing a form, then filling out their credit card info. (PayPal is also an add-on option for Gravity Forms, among many others.) Learn more about Gravity Forms.

4. Notion

Once upon a time I used Evernote, but since mid-2019, I’ve switched over to Notion to maintain to-do lists and store other important information about day-to-day business. Notion syncs automatically across all my devices (desktop, laptop, phone, tablet). Every day I use it for quick drafting—for blog posts, research notes, interviews, and conference talk outlines. Form letters and other pieces of writing or information that I use frequently (or even infrequently) get stored for easy copy-paste into email. Writers will find it useful for “composting” ideas, quotes, and book excerpts that might come in handy later.

If you’re the kind of person who has a million stickies on your desktop, or multiple documents where you’re dumping notes (then find it hard to locate what you’re looking for), then take a serious look at Notion—or Evernote, which is cheaper.

5. Dropbox

I couldn’t function on a daily basis without Dropbox, which is cloud-based storage of my work files, especially since I change machines so often. It syncs across my desktop, laptop, mobile devices, and I can also access it through any computer if I have login credentials with me.

6. Google Drive

I use Google Drive in addition to Dropbox as a cloud storage system, but specifically for those documents that I collaborate on where multiple people might need access. I also use Google Drive for storing and sharing PDF handouts or similar public links at conferences and events.

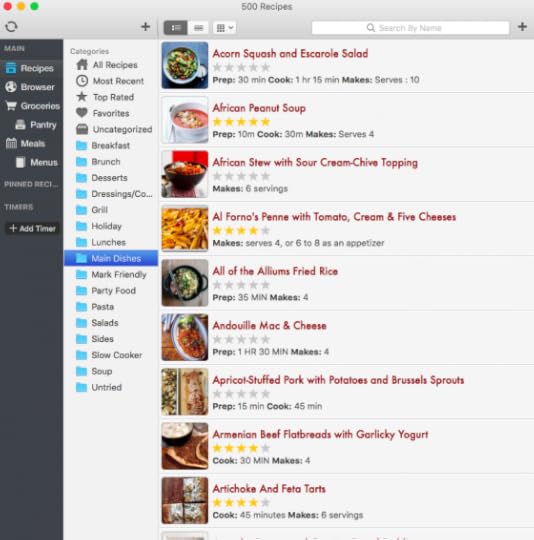

7. Paprika

Paprika is an app where I store all my recipes. It helps me meal plan during the week, generate shopping lists that get sent to email, and categorize recipes according to my own criteria.

8. LastPass

LastPass is a password manager that helps ensure you never forget a password again—or use bad password hygiene (making you vulnerable to attack). It generates strong passwords and stores your login credentials, securely and locally; whenever you go to a site that requires those credentials, it autofills them for you on a browser. You can get started for free.

9. Wave

Wave is a free, in-the-cloud accounting service that tracks income and expenses related to your business. All of my bank accounts (including PayPal) are hooked into my Wave account and allow me to see the entirety of my financial situation at a glance. It also generates invoices that clients can pay online by credit card and has payroll services if you need them. Accountants can be granted access to your profiles in Wave.

10. VisualHunt

VisualHunt is my favorite tool for finding Creative Commons and public domain images to use in my online courses, blog, newsletter, and elsewhere.

What tools are part of your daily creative life or business? Let me know in the comments.

Also: Every two weeks, I send out Electric Speed, a free email newsletter about new digital media tools and resources I’ve discovered. Subscribe.

The Exclamation Point: It’s More Than Punctuation

Photo credit: hectorhannibal on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is by author Kristen Tsetsi (@ktsetsi).

Arguing in favor of the exclamation point—which is what I plan to do—might seem like a silly endeavor. Why, people seem to care as much about punctuation in their casual written communication as they do about using turn signals on a dark, wet, winding road.

Which is to say they don’t care as much as they should. Not only are both instrumental in a world in which one person’s actions directly impact others, but they’re also effortless as acts of basic human decency go.

As someone with a background in writing, and as someone who would always rather write than speak if I don’t want to accidentally offend or confuse, I’ve dedicated a lot of time to clarity in writing. Even at home, when I want to broach a subject with my husband that has a high risk of making me nervous, writing saves us both a lot of stress and frustration. A lot.

And in my fiction, every word the characters say has to be right, and each period, question mark, and ellipsis is used carefully. Intentionally.

In recent years, I’ve seen many comments on Facebook that read only:

congratulations

Each is carelessly dropped as a reply to an elated announcement of a job offer, a promotion, a graduate degree, a new house, or some other milestone or celebration.

JOHN IS BACK FROM AFGHANISTAN!! HE JUST SURPRISED ME AT WORK OMGOMG!!!

congratulations

Every time I see it—congratulations—I have a physical reaction to that floating, not-even-capitalized word. It’s a tight twisting under my ribs, something like the adrenaline-fueled and reflexive urge to strike back when hit. It’s made me genuinely angry that someone would respond with such non-commitment to another person’s obviously deeply-felt glee.

But it wasn’t until someone wrote

congratulations

in response to a friend’s announcement that he was going home from the hospital after having survived something potentially fatal that I did the least (really) I could possibly do.

I complained on Facebook:

Can we PLEASE use one extra tiny finger tap for a ! after taking the time to tap out all the letters for “congratulations”? Is it really so hard to hit ONE MORE KEY to express enthusiasm so the recipient doesn’t get the impression that your congratulations are accompanied by an eye roll, a middle finger, or near-apathy? Or, like, if you can’t manage that, could you maybe say nothing at all? It would be more polite.

I expected my fist-banging to be met with waves of support. A great Vive la ! movement, I was sure, would sweep the world of written communication.

Instead, it generated a 54-comment debate that bled into a lunch I had the next day with two friends. One of them had seen the conversation on Facebook and had hoped I’d bring it up.

She didn’t want to use an exclamation point for “congratulations,” she said. In fact, she argued, in many cases, she used “congratulations” in the same obligatory way we might say “please” or “thank you.” Only if she liked the person in real life would she add an exclamation point. If she really cared about them, they’d merit a heart.

“But if you’re not at all excited for someone, why say it at all?” I was so vexed that I was interrogating her with black beans and rice still in my mouth.

“Because it’s just what you do,” she said. “It’s a thing you say. It’s polite.”

“But it’s not!”

That she proved my Facebook post true—people do, in fact, comment “congratulations” with underlying apathy—and that others commenting on my feed thought an exclamation point was implied in the word “congratulations” and would therefore be redundant was pretty irrefutable evidence that its absence could, and did, mean anything.

Or even nothing. One commenter on my Facebook post thought exclamation points had simply been phased out due in part to the “evolution” of writing in text messages. Another attributed it in part to feminism.

But this is the Facebook comment I found most striking, written no doubt with playful exclamation points to match the sarcasm wrapped in the euphemism:

I find it interesting the hills you decide to plant your flag?! You do you girl….!

I agree. It is an interesting hill to plant a flag on. To me, anyway, but I could talk about things like words and punctuation all day. It’s also an important hill, though, and I’ll use two arguments against the exclamation point to illustrate why.

1. “Congratulations” and other words or phrases expressing happiness or excitement don’t require an exclamation point. It’s implied.

“Implied” is a dangerous idea in the communication realm. In The Five Cs of Communication by Forbes Council Member Cheryl Keates, number one on the list is “Be clear.” Bad communication, Keates writes, “creates tension and a negative dynamic and environment.”

Implying and inferring, rather than clearly stating and correctly receiving, are considerable communication problems. How many divorces have been caused by things improperly inferred or implied? Well, we’ll probably never know, but we do know that sixty-five percent of all divorces are caused by communication problems, according to a survey of 100 mental health professionals.

If married people can’t communicate well enough in person to stay together, then it isn’t reasonable to expect that what’s implied in a text-based online conversation will be correctly inferred.

Brent Cole, who updated Dale Carnegie’s work with How to Win Friends and Influence People in the Digital Age, points out that digital tone is just as critical as in-person tone. In person, when given exciting news, we can smile in response. Hug. Jump up and down. Scream. We’ll usually find some physical way to express, “I hear you. I understand how excited you are. I will honor your elation with an appropriately positive reaction.”

Only if we dislike someone or what their news means, and only if we want them to know it, will we offer an expressionless, monotone, “congratulations,” the lack of even a capital C dully bobbing in dead eyes.

Berkeley Well-Being Institute founder Dr. Tchiki Davis, quoted in Tone in Writing 101: How Words Can Trigger Specific Emotions by Devon Delfino, says, “Perhaps because we have become accustomed to exclamation points and emojis, when they are missing, the text can seem angry or cold.” Delfino adds that people often read text as “slightly more negative” than what was intended by the writer.

Excluding emojis, Cole writes, our voice, whether written or spoken, is the only way to offer a digital smile: “Your written words are like the corners of your mouth. They turn up, they remain straight, or they turn down.”

Congratulations!

congratulations

Congratulations.

Why make the effort to convey emotion in person but not in writing?

2. Exclamation points make women look weak or are emblematic of women’s socialization to be chipper, non-threatening, friendly.

A video published by the Wall Street Journal cites a 2006 study of work emails that found 73% of all exclamations were made by women, and that “women use exclamation points more than men in emails to seem more friendly and expressive.”

In the video, three executives—former Cosmopolitan editor-in-chief Kate White, Zillow COO Amy Bohutinsky, and The Corcoran Group founder Barbara Corcoran—each read an email they’ve sent someone in a professional capacity. Bohutinsky, reading an email she’d sent someone she met at a conference, laughs at her own exclamations—“I didn’t really mean it that way”—and revises her message so that periods replace the exclamation points. After reading it aloud in the tone implied with periods, she says almost regretfully, “That sounds boring.”

Corcoran, whose email read, “It’s great to hear from you too” with an exclamation point, defends her punctuation by saying the email was addressed to a man with a big ego who “likes to be appreciated.”

White, reading an email she’d sent her editor that read “I love it” followed by four exclamation points, says she’s embarrassed by them, but, she explains, she wanted to make clear how pleased she was. “I was afraid just a period wouldn’t suffice.”

Corcoran, some time after her admission of having catered to a man’s ego with her exclamation point, says some of the most powerful men she’s communicated with “don’t even bother to put a period at the end.” She later declares that using an exclamation point as a woman “diminishes your power.”

I suppose this is true, but only if men are accepted as the standard of measurement when it comes to how powerful people should conduct themselves in writing.

Should how men do it determine how women do it?

I doubt it.

Using exclamation points, just like using turn signals, is a kindness so simple that it’s almost beautiful. In a situation in which someone is so excited about something that they share it online—where of course they’re hoping to see their delight reflected back at them—one more keystroke after a little word like “great” is a compassionate gesture. It says, “I acknowledge that I’m not the only one here. I won’t make it your responsibility to interpret my tone. I’m not afraid to be friendly or thoughtful. I respect you enough as a human being to communicate clearly.”

December 30, 2019

The Joys (and Perils) of Serial Novel Writing

Today’s guest post is by author and editor Will Willingham (@LW_Willingham).

The first 400 words of my novel, Adjustments, were written mostly to prove to my publisher, who had asked for the story, that I had no novel to write. I was a non-fiction, just-the-facts writer who had read little fiction as an adult, let alone had any interest in writing it.

The next 138,000 or so words were written to outrun the plot bearing down on me like a gravel truck on the highway. My publisher, unconvinced of my alleged novel-writing improbability, not only encouraged me to continue (and I, apparently, acquiesced), but once several thousand words and the faintest outlines of a real plot had started to take shape, she began to publish the story online in serial installments.

“It’s the way Dickens got things going,” she said. “It’ll work out fine.”

Writing a novel serially for release in real-time is a process that, like trying to outrun that truck on the highway, can be both exhilarating and exhausting. You experience the immediate delight of moving a story forward and receiving feedback from readers as the story unfolds. But it also means ongoing pressure that comes when you don’t always see the next act unfolding.

I don’t know if I would write a story in this format again. What I do know is I would remind myself of some things next time.

1. Don’t let up on the writing.

I set aside one day a week to write Adjustments. Or, that was the plan. But sometimes plans don’t work out. Over the course of a few years (the span to write this book), sometimes life events simply took precedence. Having only a few thousand words of a buffer helped me work through temporary blocks and produce week after week.

2. Be ready to improvise.

From the day I sat down and wrote those first 400 words until I wrote the very last pages, I didn’t know how the story would end. But at a certain point, I was bound by events that had occurred earlier. Sometimes as I wrote I forgot those things happened. There is, for instance, a Barbie doll head that makes repeated appearances in the story. In one episode, the main character dropped the Barbie head into his pocket. I forgot that detail when writing a future episode, and wrote as though the doll head had been returned to the glove box in his truck. When the editor caught it, we had to have a conversation about which would be more important: that he put the doll head in his pocket, or that it later reappeared in the glove box.

I recently finished watching all seven seasons of a popular television series. It took me about a month to watch what had been written over a period of seven years. Streaming television series now allow us to compress this long process into a short space, and make plot gaps that would otherwise be pinholes look gaping. The series has ended and I’m still wondering what happened with Alicia’s $6 million malpractice suit in season four.

When a writer completes the entire work before publishing, these pinholes can be filled before they become gaping. When one is writing on the fly (what you could call stand-up writing), it is a greater challenge to ensure they get filled.

At one point, we stopped releasing weekly episodes in anticipation of publishing the completed novel. As part of the editing process, we had to go back and look at those pinholes (and Barbie heads) and ensure the stories remained consistent knowing there would not be years between the chapters.

3. Hold multiple possibilities at once.

Understanding the near-immutability of the story once we had released it, and that I didn’t have a clearly identified story arc, I was careful to leave a lot of options on the table. For much of the time, I had expected a certain character to die (they didn’t). I had expected a certain relationship to launch (it’s not clear that it did). I had intended the Barbie head to mean something (let the reader decide).

And I had been playing with a possible psychological element concerning the main character and his nemesis, a disembodied woman from a prior relationship. I thought for some time that they might be the same person.

I didn’t know whether any of these possibilities would pan out. Or whether they should. So I was careful not to fully commit to any of them in my writing, but neither did I rule them out, until I had to.

4. Think in bite-sized episodes.

You’ve heard that old joke about how to eat an elephant. (One bite at a time.) Since I didn’t know the overall story arc of my elephant, I focused on the single bites. When I sat down each week to write, I had a target length in mind (typically eight to ten longhand pages). I aimed to write a complete scene with a beginning, middle and end—and a tiny sort of cliffhanger at the end to keep a reader coming back for the next installment.

5. Give the ending the time it needs.

When I wanted to bring the story to a close, I wrote an ending that was perfect. I mean, picture perfect. Every loose end was quickly tied up, every mystery rapidly solved.

My publisher gave the ending back to me, wondering if I—tired from outrunning the serial gravel truck—had been a little too eager to be done. There were no big pink bows, but there was (in the text) a large cardboard box sealed up with duct tape. And, several of the relationships that needed a longer, more nuanced closure, had been eclipsed by what the publisher viewed as a writer’s ardent desire to be done, categorically done.

Ironically, perhaps, it took stepping away from the story for two full years, during which time I’m pretty sure my serial readers thought they’d never see another word. Then, one afternoon when the conclusion was truly ready to emerge and I had a renewed sense of energy, I sat down in a coffee shop in my neighborhood and finished the novel. Minus the duct tape and metaphorical bows, we finally had a well-received book.

December 18, 2019

The Wonderful Thing About Line Edits

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress.

First Page

I opened the basement door when I got home from grade school. In the light of a single bulb, my mother thrashed around lifting dirty laundry from knee-high piles sorted into whites, light-colored, dark-colored, work clothes, jeans, and bedding. The odor of dirty wash water, bed-wetted sheets, and dank basement flowered. Twelve steps, no railing, led down.

“Mom, I got a reading certificate from Mrs. Larsen.”

I held it up, a half-sheet of paper listing thirteen titles for the 1960-61 school year.

“Hmm,” she muttered to the spinner as she yanked out a wad of wet clothes.

My mother used a two-part washing machine with a separate agitator and spinner. As she washed, she stockpiled clothes in tubs on the concrete floor while the wash water turned thick gray before going through the whole cycle again for rinsing.

“The certificate has a gold star,” I said, waving it like a wand as I picked my way down the stairs.

“Uff,” she said and lugged my father’s work clothes out of the spinner.

Every Monday, she twirled her lush brown hair into two rows of pin curls and wrapped a red silken scarf around her head. But now, some of the hairs escaped. It was 3:30 p.m. She’d been washing clothes all day, hanging them on the line to dry, and folding clean laundry into precise piles on the dining room table. We had a neighbor who washed at night and hung her first load of laundry out bright and early in the morning, but my mother would never stoop to that kind of laundry-mandering. No. She had integrity in her washing protocols. Monday was wash day. Not Sunday night and Monday.

Now, she surged to the finish with only two more loads to hang on the line before she could brush out her pin curls, put on some lipstick, and whip up a meal in time for a 5 p.m. supper when my father got home.

I knew she was busy. She always was. It wasn’t easy to be a post-war wife in Middle America with the high demands of housewifery bearing down on her.

The certificate flagged in my hand.

I stood beside her, fidgeting with the shiny silver toggle on the spinner. I’d heard a confounding female fact on the playground that day.

I said, “Where do babies come from?”

The tie on the top of her head waggled. She paused, both arms deep in the spinner.

“From a mother’s stomach.”

That was not a satisfactory answer to my seven-year-old mind, not even an S-minus answer, the shaming grade I tried to avoid on my report card.

I said, “Marlys—her mother just had another baby—said they come from a uterus and that they’re born out of a vagina.”

My mother snapped her face towards me.

“That little snot,” she said and sneered at the spinner.

She hit the switch. The spinner whirled in a whiny din as the water poured then trickled from the reddish-pink drain hose. She grabbed the metal perforated spinner basket still spinning. It jerked to a stop, and she wrenched my father’s green work clothes from the cylinder.

“Do they?” I said.

“Do they what?” she said, as she heaped the laundry basket high and mounded as a full-term pregnancy.

“Do they come from a uterus and get born from a vagina?”

These were big words. Maybe my mother didn’t know them. Maybe Marlys was wrong. Marlys was Catholic after all, and as such, her veracity was questionable by worthy Lutherans such as us.

I remained silent. Good thing. Or I might not have heard her exhale a prolonged weary “yes.”

First-Page Critique

When I met with my mentor in his Greenwich Village duplex, we’d sit side by side at his dining room table walled in by hundreds of books. Armed with his trusty Mont Blanc, Don Newlove slashed through my sentences, slathering them with ink, making me read my version first, then his, and tell him why his was better!

For about eight months we did this, until I bridled at my mentor’s “improvements.” By then it hardly mattered, since I’d learned most of what Don had to teach me, which boiled down to this: Never let a dead, droopy, or sawdusty sentence—a sentence not worth reading once, let alone twice—stand. In those eighteen months, thanks to Don I became the next best thing to a poet: a stylist.

I chose this first page as the last of this series of critiques (I’m taking a break) since I felt it was pretty strong and wanted to end on a positive note. That said, it can stand improvement. At the macro level it suffers from a blurred or misplaced focus: the reading certificate isn’t the point of the scene, really; the fact learned on the playground is. The certificate is just a subterfuge or decoy. But unless we know that up front our attention is misdirected, and the scene’s source of tension is lost.

Rather than discuss the page, for this last critique instead I thought I’d do for it what Donald Newlove used to do for me: revise line-by-line. Some of my revisions come down to cutting, changing, or moving a word or two; others are more substantial. The point of line edits isn’t to say, “My way is better!” (though Don’s revisions usually were), but to give a fellow author the gift of a fresh pair of eyes and ears and alternatives to reflect upon. The great thing about line edits: unlike many gifts, they can be accepted or rejected as one sees fit.

Compare my revision with the original. Even if you don’t agree with my changes, you might consider why I made them. Is the sentence in the right place? Does it land on its feet, i.e. with the most important part saved for last? Does it say things that might be better left implied? Is it true? Substantial? Relevant? Concise? Grammatical? Elegant?

Finally, assuming you agree that the original page here wants some revising, how would you revise it differently, while still preserving the author’s style and voice?

Revision

I opened the basement door. Under the light of a single bulb, my mother thrashed around, lifting dirty laundry from knee-high piles, sorting it into plastic tubs: whites, lights, darks, work clothes, jeans, bedding. Smells of wash water, bed-wetted sheets, and dank basement flowered. Twelve steps—no railing—led down. I’d come home from school with something on my mind and something in my hand.

“I got my reading certificate from Mrs. Larsen,” I announced, brandishing the half-sheet of paper listing thirteen titles for the 1960-61 school year.

“Hmm,” Mom muttered to the spinner. She yanked out another wad of wet clothes.

“It’s got a gold star,” I said, waving the certificate as I picked my way down the stairs.

“Uff.”

Mom yanked Dad’s work overalls out of the spinner. She used a two-part machine with a separate spinner. Before going through each rinse cycle the water turned thick gray. Monday mornings, she’d twirl her lush brown hair into twin rows of pin curls and wrap it under a red silk scarf. By now some of the hairs escaped. It was 3:30. She’d been doing laundry all day. Our neighbor, Mrs. Fisk, washed on Sunday nights and hung her first loads out bright and early Monday mornings. Mom would never stoop to such laundry-mandering. She had integrity. Monday was wash day. Not Sunday night. Monday. With only two more loads to hang before she brushed out her pin curls, smacked on some lipstick, and whipped up a meal by five p.m., when my father got home, Mom surged to the finish. To be a wife in post-war Middle America wasn’t easy.

I stood next to her, my right-hand fidgeting with the silver toggle on the spinner, my left clutching the drooping certificate, remembering the confounding fact I had learned from Marlys during recess. I asked:

“Where do babies come from?”

Mom paused, both arms deep in the spinner. The tie on the top of her head waggled.

“From a mother’s stomach.”

To my seven-year-old mind this was not even an S-minus answer.

“Marlys said they come from a uterus and that they’re born out of a vagina.” (Marlys mother had just had another baby—her fifth.)

My mother snapped her face towards me. “That little snot.”

She hit the switch. With a whiny din, the spinner whirled. Gray water poured then trickled from the reddish-pink hose. She grabbed the perforated, still spinning basket, jerked it to a stop, and wrenched Dad’s overalls from its maw.

“Do they?”

“Do they what?” Mom heaped laundry.

“Come from a uterus and get born from a vagina?” These were big words. Maybe Mom didn’t know them. Maybe Marlys was wrong. Marlys was Catholic, after all, and as such questionable by worthy Lutherans like us. The din ended. A good thing, or I might have missed Mom’s weary reply:

“Yes.”

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

Note: The publisher of Your First Page is offering free shipping if you order the book directly from their site. Use code YFPfreeship.

December 17, 2019

Art Versus Commerce: Q&A with Author-Cartoonist Bob Eckstein

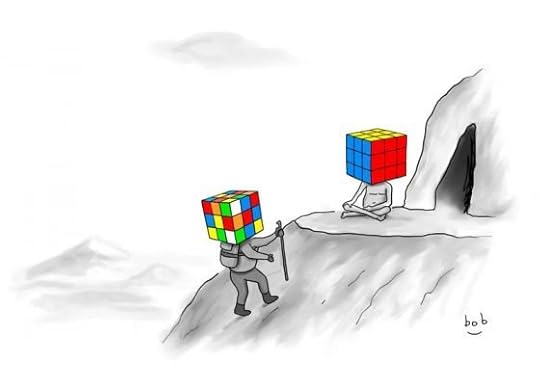

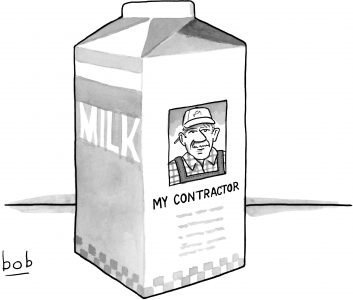

In this interview, Bob Eckstein discusses art vs. commerce, newspaper/magazine cartoons vs. television as communication delivery systems, the influence of just the right validation, and much more.

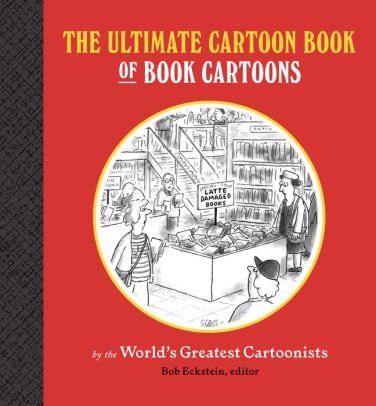

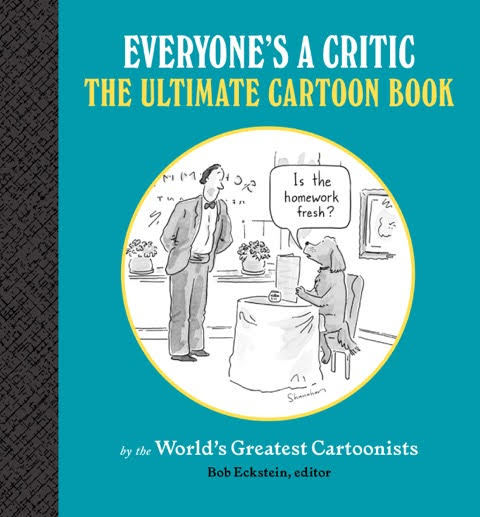

Bob Eckstein (@BobEckstein) is a New York Times best-selling author, an award-winning illustrator, New Yorker cartoonist, and the world’s leading snowman expert. He was nominated Gag Cartoonist of the Year twice by the National Cartoonist Society. His work has appeared worldwide, and he was a columnist for many publications like New York Newsday and TimeOut New York and was a regular contributor for The Village Voice, New York Times, New York Daily News, National Lampoon, SPY, Playboy, MAD, and many publications worldwide. He has spent the past years speaking publicly and writing OpEds against online shopping and raising awareness for independent bookstores.

Atlas Obscura calls him a national treasure. His new book is Everyone’s A Critic: The Ultimate Cartoon Book by the World’s Greatest Cartoonists and The Illustrated History of the Snowman.

He lives in New York City and teaches writing and drawing at New York University.

KRISTEN TSETSI: With a skill like yours and the availability of things to sketch on and with, it seems like it could be a challenge to not sketch all the time the same way people, with the ease and availability of smart phone cameras, take pictures so frequently that morning show people tell us to put down the phone, live the moment rather than seeing it through a bright screen.

Do you ever find it hard to sit and absorb rather than take out a drawing or writing instrument?

BOB ECKSTEIN: I love your question, but it’s actually not the case at all. Not that I don’t love my work, but I am never doodling for fun or drawing for recreation as I have so many assignments and clients patiently waiting for work from me.

Like that old episode of I Love Lucy with the conveyor belt in the chocolate factory, my deadlines are relentless and if I’m drawing it’s with a purpose.

There have been times when I presented myself with a day off and went outside with oil paint and did something, but even then the end results turned out to be for a book cover. I think I did it in response to criticism that I work mostly on computer. I work in traditional materials every so often to prove to myself I’m not a fraud, or something.

The advancement of technology has been helpful in addressing the new time demands of my clients, but I see it just as my evolving toolbox and it hasn’t changed the frequency or infrequency that I draw and work. Listening and absorbing has always been a big part of getting ideas (and jokes), and I think my attention span for that remains the same.

I love what you say (in a PBS segment featuring you at the Miami Book Fair) about the magical metamorphosis that takes place somewhere in the space and time between one of your cartoons being shown to someone privately and the same cartoon being published:

When I do cartoons, I can show it to a friend, or my wife, and she’ll say, “Oh, it’s okay…,” but when it gets printed in The New Yorker, all of a sudden, “Wow, that’s funny!” All of a sudden, it changes its status.

My husband and I were just talking about that phenomenon, and he reminded me of an episode in the final season of Seinfeld. Elaine, who can’t figure out why everyone around her is calling a New Yorker cartoon brilliant, meets with the New Yorker editor under the guise of wanting to find cartoonists for the J. Peterman catalog. Finally, she gets around to demanding an explanation of the cartoon, but the editor can’t give one. He has no idea what it means—he just liked the art.

What are your thoughts about the power of publication (or production) by the right entity to persuade many us to believe—right or wrong—“Yes, this is wonderful”?

Ahh, the evil of validation. While I did say that, and I believe it true, I do think it’s unfair.

Ideally, we would all be able to follow that advice of, Write for yourself. Make cartoons that make YOU laugh. Etc. Life is not like that. It’s about the response of others and the New Yorker is, wrongly, the touch of God that tricks us into thinking that because it’s in those hallowed pages it must be comedy gold.

Ideally, we would all be able to follow that advice of, Write for yourself. Make cartoons that make YOU laugh. Etc. Life is not like that. It’s about the response of others and the New Yorker is, wrongly, the touch of God that tricks us into thinking that because it’s in those hallowed pages it must be comedy gold.

Now, I have always followed one bit of advice that echoes in my head, and it’s that as a writer or illustrator or cartoonist your number one job description is to communicate properly your idea. Being self-indulgent is for fine artists.

So I’m not suggesting one work in a vacuum, but I’m with Elaine on this one. Good for you if you got published in the New Yorker or New York Times, but that’s not the end-all measurement of the worthiness of your writing or how funny you are. At least that’s what my mom told me.

Regarding communicating properly—and at the risk of this sounding like a silly question, please know I take punctuation seriously—what are your feelings about the general use, misuse, overuse, or underuse of the exclamation point? This question is inspired by a recent post in my Facebook feed in which a man survived what should have been a fatal heart incident, and to which someone responded:

congratulations

I love to discuss this as I DO think I know something about this.

Correspondence with friends should be not held to the same standards as writing for mass consumption. It’s ridiculous. I even allow for bad publication. Friends don’t judge friends.

Now, if you want to have an argument over whether or not your Facebook friends are really your friends, that’s a whole other discussion. But I say, exclamation marks can be used to reflect the personality of that friend to their heart’s content, or the heart at least stabilized in the case you cited.

Now, for professional writing, you better have a good reason to use this punctuation, and it should surface only when absolutely necessary, like when the quote is being screamed like, “Throw me flotation device!”

You say in an interview at Cartoon Collections that choosing to be a cartoonist wasn’t the smartest business move, that professionally, in the cartoonist hierarchy, you’ve grown “Zero.” You also say, though, that you don’t put in the work it would require to be what you call a top tier cartoonist because you’re busy doing other things.

As examples of those things, you recently spent a busy few days live-drawing the Miami Book Fair, participating in a podcast, appearing on TV, and giving a talk.

If you were to decide being your definition of a “top tier” cartoonist were your priority, how much would you have to give up to allow yourself the time to work toward it, and what would you miss most about what you’d be losing?

Ooo, these questions have some bite to them. I like it. I forgot I said that, but can clarify what sounds, to my ears, as a little flippant.

It’s true I don’t put in as much focus as it requires to be an excellent humorist. My day is filled with too many meetings and such which my other projects require. I contend when one finishes a book that’s when the real work begins, and I do what’s necessary to create exposure for a new title.

I am being disrespectful to the profession of cartooning if I have the arrogance to think spending a few hours a week on it is enough. And I’m disappointed when I hear others who think they are weekend cartoonists. It’s disrespect. I don’t say I’m a weekend heart surgeon. I’m certainly not going to improve that way, either, without the devotion to the craft.

But with so many great venues for cartoons now gone, like Playboy and MAD, it is a bit foolish not to shift my attention to where I can reach the most amount of people. At this moment, that is me public speaking (often for one of the issues I feel strongly about, like raising awareness for independent bookstores) or books.

In the same interview at Cartoon Collections, you say your interest in cartooning came late. What were you interested in before that, and what is “late”? What’s a typical age, and what inspired your first cartoon (or cartoons?), if you recall?

I have found the cartoonist community to be warm and kind. I have become good friends with many. I have heard over and over how they drew cartoons as a kid, read comics and so forth.

I loved drawing as a kid, but I loved Sports Illustrated and did not follow cartoons. Never dreamed of doing them. Didn’t read the New Yorker except once in a blue moon.

I loved drawing as a kid, but I loved Sports Illustrated and did not follow cartoons. Never dreamed of doing them. Didn’t read the New Yorker except once in a blue moon.

I wanted to illustrate in magazines and took myself too seriously. I was writing humor on the side but wasn’t thinking cartoons until later. And that was on a dare from a friend who was a cartoonist, the great Sam Gross.

I started drawing gag cartoons when I was 45. That’s starting late. And I sincerely regret it. I goofed. But since I did, I have been trying to make up for lost time. I jumped all in trying to read every old New Yorker and studying cartoon books. I have now a pretty good knowledge of cartoons.

You answer some readers’ questions on Goodreads, and in one of them you credit the TV show The Odd Couple with having taught you humor and ultimately as being responsible for your career as a humorist. What was it about their humor in particular—versus that of Get Smart, say—that grabbed you? What did they teach you about humor writing?

My answer could’ve been Get Smart. It just so happened it was the Odd Couple that was on the TV set. I didn’t vet the shows, but there were subconscious lessons there from comedies I loved, like the Mary Tyler Moore Show or shows that were too old for me, like All In The Family.

It was only much later could I tell you exactly what I learned when I studied old Bob & Ray tapes or every word George Carlin uttered, learning timing (yes, cartoons have timing) and tension and so forth. I learned a lot about humor as a kid watching The Odd Couple, but exactly what I’m not sure except that being funny was powerful and could get you attention. I learned I wanted to be funny.

How did you choose your signature—just Bob, underlined?

It began when signing snowman books. I stumbled across making my name into a smiling face. Later, when I started making cartoons, I used it as it was the simplest way to sign my name.

It began when signing snowman books. I stumbled across making my name into a smiling face. Later, when I started making cartoons, I used it as it was the simplest way to sign my name.

Can’t get more unpretentious than just bob.

You’re finishing a graphic novel, now, an 1850s diary about the search for Arctic explorer Sir John Franklin, who by 1850 had been missing at sea—presumed dead, but not found—for four or five years. What attracted you to the story of Franklin? And whose diary is it?

It’s the diary of a fictional character in a fictional adventure that is based on the real facts surrounding one of the greatest Gothic mysteries in history, which until now wasn’t solved (the missing ships were recently located!).

That’s the set-up. The story is about the human condition, love, and all of our quests for validation. It’s a comedy and romance.

In a sit-down on the Weekly Humorist podcast Talkward, you discuss the adaptation of your book Footnotes from the World’s Greatest Bookstores into a TV series. You say the show doesn’t necessarily need to focus only on big-time bookstores but could also include new bookstores, or “bookstores that people should learn about.”

In a sit-down on the Weekly Humorist podcast Talkward, you discuss the adaptation of your book Footnotes from the World’s Greatest Bookstores into a TV series. You say the show doesn’t necessarily need to focus only on big-time bookstores but could also include new bookstores, or “bookstores that people should learn about.”