Jane Friedman's Blog: Jane Friedman, page 90

September 12, 2019

What Happened After I Lost My Agent—Twice

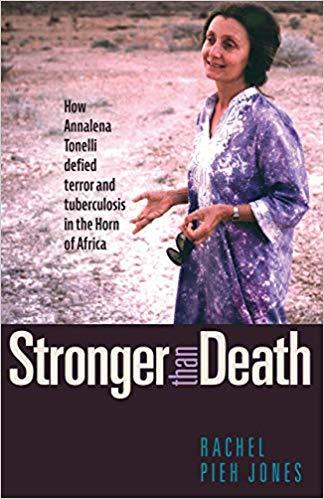

Today’s guest post is by Rachel Pieh Jones (@RachelPiehJones), author of Stronger Than Death.

In 2012 I published a Modern Love essay in The New York Times. The essay led to landing a literary agent for a memoir. For two years, I wrestled with the proposal, which never quite satisfied her standards. I developed a second proposal, which also failed to meet her approval. A third, same failure. There were some bizarre email exchanges and eventually, I ended the working relationship.

I failed. I’d had my chance. I had an agent, but couldn’t produce a book worthy of being published, or even shopped around. I thought this was the most discouraging thing that could happen in my writing career.

A year later, I summoned my courage and sent another round of agent queries for that third book proposal, narrative nonfiction based in Africa. I signed with a new agent! After a cursory round of edits, she sent out the proposal. An editor at a big five publisher was interested. We had an encouraging call but she came back a devastating “no.”

I was told readers didn’t care about Africa. I was told my proposal sounded more like a magazine piece than a book. I was told this wasn’t the time for global stories or biographies.

This agent and I parted ways.

I thought that first agent failure was discouraging. But now, I had been so close, the Big Five! And I’d failed again. It felt like running a marathon and collapsing fifty meters from the finish.

What was wrong with me? I expressed my despair to a writer friend, said I would quit. He said, “You can lay on the floor and cry for one day. Tomorrow, get up and get back to work.”

I did exactly that. But this time I interrogated why, exactly, had I come up short with these proposals, agents, and editors? Was it my writing, my ideas, my methods?

I refused to believe that American readers didn’t care about Africa or that now wasn’t the time for biographies. I knew my story was a book, not a magazine article. It was an epic adventure spanning several decades and multiple countries, a story that turned conversations about race, faith, humanitarian aid, and sexual violence upside down. I’d been told my writing and this story were powerful.

What was I doing wrong?

After a few months of wallowing in my perceived failures, I realized I had not really done the work of targeting. My book was an international story focused on issues of contagious disease, interfaith relationships, and social justice. These words were much more specific than “narrative nonfiction” or “biography.”

I searched for publishers with books in these categories, who would take me without an agent. I wanted to pitch the story the way I saw it, as a woman who lives in Africa and engages in development work, not through the lens of a New York City literary agent.

I searched for publishers with books in these categories, who would take me without an agent. I wanted to pitch the story the way I saw it, as a woman who lives in Africa and engages in development work, not through the lens of a New York City literary agent.

I sent the proposal to Plough Publishing. We had a phone call. I knew immediately this was the place for my book, I could tell they would honor the story, they understood what made this story resonate now. We signed and the book will be published October 1, 2019.

Then they bought my next proposal, which was loosely based off the proposal that landed my first agent way back in 2012.

Here’s what I learned, lessons I believe apply to writers at every stage.

You are not a failure. Your book may have failed to connect with an agent or an editor. This is not a reflection of you, the human. You are not an idiot, loser, or disappointment. You are not ridiculous. I spoke all these words over myself and they were all lies. I felt disappointment, like I had failed, like I had reached ridiculously above my abilities. But I had tried something hard, had made brave choices, hadn’t quit, and knew what I wanted, even if I didn’t quite know how to achieve it.

Press through discouragement. Don’t give up. If this is what you want, keep doing the work. Speak words over yourself like brave, persistent, creative, strong, resilient. Feel the discouragement, don’t deny it, but then don’t settle there, either.

Have a writing community. Find that friend who can let you cry for a day and who will then push you back up. Do the same for your writing friends on their rejection days.

Tweak. Listen to feedback, especially the rejection feedback, and revise. Decide what you are willing to change and what is essential. Yes, kill some darlings. But don’t necessarily kill them all, or you’ll risk losing distinctiveness.

Focus the pitch. Know your niche. The more specific you can be, the stronger your pitch will be, and the easier it will be to target the right agent or publisher, and eventually, the right reader.

Take a risk. Maybe it is time to drop the agent with whom you just aren’t connecting, or who doesn’t grasp your story and vision. This requires courage and humility. It feels really good to say, “my agent.” But if it isn’t a great fit, that phrase might not ever transform to, “my book.” Maybe it is time to Google off the beaten path and find a unique publisher or different agent.

Find your people. Your book is not for everyone. I wrote a guidebook to the country where I live, Welcome to Djibouti. You should not buy it, unless you are coming here for work or touring. Knowing who your book is not for can help you know who it is for. Identify your audience as precisely as possible, even in the early pitching stages.

Know your story. Knowing what happens chronologically is one thing but being able to describe what it means is another. The ‘what happens’ keeps a reader reading, but the ‘what is it about’ compels a reader to feel connected to a story, and this is what will eventually sell the book to an agent or publisher, and your reader.

I’m thankful for the input I received from the two literary agents, even though we weren’t successful together. My writing and my understanding of the publishing world are better because of our interactions. But I’m also glad I was willing to step out on my own and not give up.

You can do this, don’t take no for an answer. Hear it, adjust as necessary, and press on. There is an audience for your work, you just need to find it.

September 11, 2019

How to Evoke a Unique, Human Character—Not a Generic One

Photo credit: D. Scott Lipsey on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

Lainie was scraping the last bit of peanut butter out of the jar when the land-line rang. She didn’t pick up; her friends only called her cell. The ancient answering machine clicked on and a perky, professional voice chirped “Tini Ferrari here, KNWD-TV?” Lainie knew that name. Pronounced teeny. Everything she said sounded like a question. “I’m phoning about a possible New Year’s Eve interview with Madeleine Stanton? I understand you were Ohio’s first millennium baby? I’d love to talk to you about a feature we’re doing, now that you’re turning twelve. Give me a call?” Tini gave a phone number and clicked off.

A feature on 2K-babies, on TV! She’d be the star, having come into the world at precisely midnight at the turn of the millennium to 2000. It had been years since anyone had mentioned it. It might be fun to be in the spotlight for a few minutes. An image of herself surrounded by kids at school flashed through her mind. But what if something went wrong—if she belched, or got sweaty? Or said something stupid? If she messed up on TV? The worst moment of her life would become unerasable entertainment online for the world to see forever—potential boyfriends, colleges, employers—it could end all hope of a normal life!

Anyway, Dad and the Uncs wouldn’t like it. They’d probably freak-out at the attention it would bring to the family. Lainie was wondering whether to ask her dad when she heard the stamp of his boots in the mudroom. A minute later he walked in in his stocking feet, face red from the cold, briefcase under one arm.

“Hey, kitten,” he said, patting her shoulder as he moved past her toward his study.

Lainie followed. “Dad, wait! We—er, I—just got this phone call.”

He went to his desk and started pulling papers out of his case, but raised an eyebrow as though listening, so she pressed on. “That TV reporter Tini Ferrari? She wants to interview me! On TV! They’re doing a story on kids born at the millennium. What do you think? Should I do it?” She blurted out the reason she was afraid he’d say no. “Do you think it would bother the Uncs? I mean, she’s not gonna ask about, well, about what happened . . .”

“Hmm,” he said, pawing through the papers and frowning. “So, do you need a new dress? Or to get your hair done? You can take my credit card.”

“Dad.”

He looked up blankly.

She couldn’t stop herself from mocking him. “Get my ‘hair done’?”

“I’m sorry, honey—I guess I wasn’t listening. Is it important?”

Lainie sighed with frustration, but seeing the anxiety on his face—anxiety that meant he had another long evening of student papers to grade before he could even think of working on his book—she ran to hug him. “No,” she said. “Never mind. Hey—it’s Grampa’s chili night! With cornbread. I’m starved!”

In her room, Lainie tore through math, then English. Sliding her textbooks back into her pack, she thought of her dad and his weary face. He was so desperate to publish a book. He needed it to keep his job at Kenwood college. The writing was practically done. Still, for some reason he couldn’t quite finish it. The stress was making him weird. Every night he came home and went straight to his study, emerging only for a quick dinner. She couldn’t imagine what else her dad would do if he lost his teaching job. As far as she knew, he didn’t have any actual skills.

First-Page Critique

This first page is really closer to two pages, but I’ve decided to let the overage stand to make a point that I’ll get to later on in this critique. But first let me talk about the things that are working well here. There are many.

This opening starts off with an inciting incident. It does so dramatically, through the action of a telephone (“land-line”) ringing. Of course, from the first sentence we have no way of knowing for sure that the phone call is important, let alone that it’s the action or event that will yank one or more protagonists out of their status-quo existence and into a plot. But given the event’s positioning in what is arguably the most valuable piece of real estate in any story—the first sentence—it’s a safe bet that this phone call will amount to something greater than a robocall or a wrong number.

And note the clever introduction within the same sentence of what at first glance might seem like an arbitrary and irrelevant, if not an impudent, detail: the protagonist, Lainie, “scraping the last bit of peanut butter out of [a] jar.” How can such a trivial detail possibly justify its claim to the front-row center seat of sentences? By doing what every sentence in a work of fiction—or, for that matter, nonfiction—should at the very least try to do: evoking character. I’ve said it elsewhere: Anything we do as writers that evokes character is to the good. Conversely, every sentence or passage we write that doesn’t in any way evoke or convey some quality or essence of humanity, that merely supplies information about or describes things, should arouse suspicion.

And just what does “scraping the last bit of peanut butter out of [a] jar” convey about the character named Lainie? First and foremost: that she’s a human being, for only human beings scrape peanut butter from bottoms of jars, at least as far as I know. But the action also tells us something more about Lainie; namely, that she is the type of person who scrapes peanut butter out of the bottom of a jar. If only we knew whether she does so with one or more fingers, or with knife or fork, it would tell us even more, but never mind; you get the idea. Characters are most efficiently and effectively defined by their actions, by the things they do, and that includes the littlest things, like whether they put their stockings or their skirts on first (to “skirt” a cliché).

The point is that with this first sentence we not only get a telephone ringing, and, with it, the expectation of some important or fateful news, we get a human character—not a generic human character, but one who is already particular.

The next thing this opening does well: it thoroughly and consistently engages the experience of a character by way of its third-person narrator. It does so through a technique called free indirect discourse, also known as free indirect style or method — or, in sexier, r-rolling French, discours indirect libre. All that means is that the narrator is free to dip in and out of the point-of-view character’s (in this case Lainie) interior dialogue or stream-of-consciousness whenever he/she/it (third-person narrators being distinct from their authors and nameless, we can’t assume their sex, or even if they’ve got one) wishes.

And so when we read “The ancient answering machine clicked on and a perky, professional voice chirped …” we intuit that the opinions expressed by the words “ancient” and “perky,” and the comparison of the “professional voice” to a bird’s, reflect not only Lainie’s consciousness, but her vocabulary. They are her words, or anyway they’re the sort of words she would use to describe those things.

Read through the rest of this first page, and time and again you’ll find Lainie’s personality infusing the third-person voice, to where at moments it reads exactly like a first-person narrative: “Anyway, Dad and the Uncs wouldn’t like it. They’d probably freak-out at the attention it would bring to the family.”

Should you as an author ever find yourself torn between first and third-person, you can do worse than avail yourself of the free indirect method. It lets you have your cake and eat it, too.

Now to the issue I mentioned in the first paragraph. My one problem with this opening comes with the last paragraph, where from Lainie’s perspective we learn of the stress her professor father, who must “publish or perish,” has been under, having so far failed to do the former.

Now to the issue I mentioned in the first paragraph. My one problem with this opening comes with the last paragraph, where from Lainie’s perspective we learn of the stress her professor father, who must “publish or perish,” has been under, having so far failed to do the former.

Though this insight into her father’s predicament is valuable, it comes in the wrong place, without motivation, with Lainie tearing “through math, then English” textbooks in her room. For no particular reason in the midst of her studies she thinks of “her dad and his weary face.” Might not the same thought and the awareness that comes with it be better motivated and more moving if it happened earlier, when she sees the anxious look on his face, rather than when she thinks of it later?

Otherwise, this is a very strong first page—or rather two strong ones.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

September 4, 2019

The Challenge of Sensational Story Openings

Photo credit: Petr Meissner on VisualHunt / CC BY

Today’s post is by regular contributor Peter Selgin, the award-winning author of Your First Page. He offers first-page critiques to show just how much useful critical commentary and helpful feedback can be extracted from a single page—the first page—of a work-in-progress. Learn more about getting a first-page critique.

First Page

“When the helicopter comes, we will carry you. You will want to help, but you should do nothing. You must not try to move yourself. We will do everything.”

It was Angel Lady again, her face a few inches from mine. I stared into her strange eyes—big, shiny and metallic blue. In each eye I saw my mirrored reflection. There was two of me. Both of me have a white beanie on. Both of me have an oxygen mask on my face. She began to stroke my forehead, slowly, back and forth, back and forth. Her finger was soft and fuzzy.

“Just relax, think calm thoughts. Think of a place that is warm and peaceful, where you are calm and happy. Relax.” Her voice was soothing but sounded a bit different. Angel Lady was German maybe, or Swiss?

Why am I lying on the ground? Where am I?

“Are you feeling any pain?” she asked. I moved my head slightly, enough to answer “no.”

“Are you warm enough?” I nodded my head “yes.” The slight effort it took to answer was tiring. Trying to think was tiring. The physically conditioned body I had trained so hard for was now motionless—my limp arms and legs too weak to move. My sleeping bag, bundled around me, felt soft and warm. I just wanted to drift into sleep and closed my eyes.

No, NO! Open your eyes, open your eyes—you can’t go to sleep, you have to keep your eyes open or you’ll go to the black place where you can’t breathe! Matt said you have to breathe—he’ll start yelling at you again if you don’t breathe.

I jolted awake, more conscious than I had been for, well, I had no idea how long. I looked at rocky ground all around me. I saw snow-covered giant mountains in the distance.

I know where I am. Renjo La . . . Himalaya mountains.

I remember what happened.

I began to shake, hit by that rare kind of terror that comes with realizing you are probably going to die.

First-Page Critique

The effectiveness of an opening comes down to questions. The questions are always the same: who, what, when, where, how, and why? What varies is which questions are raised and answered and to what extent. Answer too many questions, and you burden readers with irrelevant information and risk undermining suspense; answer too few, and you create false suspense; confusion.

Even when an opening achieves a good balance between questions raised and answers given, those questions and answers may not be the best ones with which to equip readers for the journey through a story or a novel—or, in this case, a memoir.

The answers provided by the sensational opening of this memoir are as follows:

Where: Renjo La Pass in the Everest region of the Himalayas

When: Contemporary, certainly within the last half-century

What: An expedition, probably for the purpose of mountain climbing, during which the narrator has been incapacitated and is delirious

How: Probably she took a bad fall and broke one or more limbs, or succumbed to altitude sickness, or both

As for questions, the main one it raises is: Will the helicopter arrive? Will the narrator be rescued? The question calls attention mainly to an anecdotal experience. Anecdote: “a short amusing or interesting story about a real incident or person.” While mountain climbing in the Himalayas, I succumbed to altitude sickness, broke my leg, and had to be airlifted to a hospital. That’s terrific fodder for a tale told to friends over cocktails. But is it enough to draw me into a book-length memoir? Assuming it draws me in, does it point the way to the memoir’s main theme? (The subtitle of this memoir, “A Woman’s Journey to Save Her Wild Child,” leaves me with some doubt.)

But putting that aside, let’s consider two questions not raised by this first page, namely Who? and Why? Who is this narrator? What circumstances and motives brought her to this treacherous mountain pass? If readers wonder at all, they will do so vaguely, their curiosity about such things overshadowed by the sensational drama at hand. Which points to a potential problem with sensationally dramatic openings: they leave very little room for character evocation. Apart from the fact that she’s incapacitated, the one thing we learn about the narrator from this first page is that she’s afraid to die, but then aren’t most of us? Under the same circumstances, who wouldn’t respond more or less as she does? Toward revealing character, the opening doesn’t take us very far.

But supposing, for argument’s sake, that this first page told us something more about the narrator, something to make us as curious about who she is as to whether or not she’ll be rescued? Supposing there were some hint of a tragedy in her recent past, something left behind on this expedition? Supposing we learned that she is eighty-six years old, or that she’s been through a bad break-up, or quit her job as a lawyer for a corrupt pharmaceutical company, or done several tours as a soldier in Afghanistan or Iraq, or survived the collapse of one of the towers at the World Trade Center? Or that before undertaking this voyage she spent the entirety of her life in a small midwestern town. If only we knew any one such thing, how differently this first page would read.

In Black Wave, a memoir about a family sailing trip turned disastrous by a freak storm, within two paragraphs authors Jean and John Silverman do more than just put us into a disastrous situation; they engage character:

Below deck in our catamaran sailboat, my husband, John, stood in the doorway of our tiny stateroom. I can picture him there in that instant before everything changed. Our four children—we had pried them away from their suburban world for a thousand reasons—were busy elsewhere on the boat, settling in for the night. John had just told me how long it would probably take us to get to Fiji, our next destination by way of Tonga. After Fiji and Australia, the plan was for the kids and me to head home to the States while John stayed behind long enough to clean up the Emerald Jane and sell her.

I was propped up in bed with a laptop as John chatted from the doorway. He hadn’t had a drink since his big meltdown in the Caribbean, and I was pretty much in love with him again. We had done what we set out to do two years earlier when we first set sail. Along the way, our children’s eyes had opened to the beauty of the world. The kids were very strong characters now, very different from when we began. We loved them in new ways—maybe deeper ways, because we had taken the time to finally get to know them.

Like the one under discussion, this memoir opens in medias res, “in the middle of things.” It, too, is about an adventure that turns disastrous. But though the opening telegraphs that disastrous event (“before everything went wrong”), the emphasis is on who rather than on what. In two paragraphs we learn:

that the narrator and husband’s marriage has been troubled;

that the husband, John, may be an alcoholic;

that there has been at least one recent “meltdown”;

that the children are growing, changing, forming “strong characters.”

Most telling is that last sentence: “We loved them in new ways—maybe deeper—because we had taken the time to finally get to know them.” Though about the children, from that sentence we infer that something of the kind applies to the narrator and her husband as well, that in confronting disaster they’ll learn things about themselves and each other. Understanding, revelation, and growth: that’s what most good memoirs are, ultimately, about. Not anecdote; awakening.

An anecdotal experience can play a crucial or central role in a memoir and even serve as its main action. But however sensational, unless we know the people to whom they happen, dramatic incidents in and of themselves are fairly meaningless. Ideally, the opening of a memoir should make us as curious about the characters as about what has happened, or will happen, to them. If the author can add that dimension to this opening, it will be very strong indeed. As it stands, it is merely sensational.

An anecdotal experience can play a crucial or central role in a memoir and even serve as its main action. But however sensational, unless we know the people to whom they happen, dramatic incidents in and of themselves are fairly meaningless. Ideally, the opening of a memoir should make us as curious about the characters as about what has happened, or will happen, to them. If the author can add that dimension to this opening, it will be very strong indeed. As it stands, it is merely sensational.

Your turn: How would you assess this opening? (Be constructive.)

September 3, 2019

How to Build a Compelling Narrative Arc for Your Memoir

Photo credit: styf on DepositPhotos

Today’s guest post is by author and nonfiction writing coach Tanja Pajevic (@tpajevic).

After 20 years of teaching writing, I continue to be amazed at the transformation that occurs for writers of memoir. The process of sifting through the pivotal events of one’s life to shape them into a cohesive narrative enables writers to step into their power at a deep level. At the same time, writing about your life can be challenging. What do you include and what do you leave out?

A compelling memoir must be shaped. That’s why I encourage my clients to clarify their narrative arc before they start writing. Otherwise, it’s too easy to go down the rabbit hole—and waste weeks, months or even years of writing time.

Here are five steps to help you build a compelling narrative arc for your memoir. Let’s start with the most important step: clarify your story’s scope.

1. Clarify Your Scope

Compelling memoirs cover a particular time, theme or transformative event. They don’t cover your entire life—that’s autobiography.

Seems pretty straightforward, right? Most folks think so, until they sit down to write. Before they know it, they’re wrestling with an octopus.

You must choose. What you leave out is just as important as what you keep in. The following questions will help you narrow it down:

What is the specific challenge or time period you’d like to write about?

What is the transformation that occurred?

What did you learn as a result?

After my mom died, I wrote The Secret Life of Grief: A Memoir because I wanted to explore how to grieve consciously in a society that barely recognizes grief. This was my main theme.

Once you have that, you can begin to shape your narrative arc. Something needs to be figured out, discovered or transformed. This central question provides the story’s tension or conflict—the key to keeping your reader turning the pages.

2. Start with the Big Rocks

Stephen Covey is well known for his “rock, pebbles and sand” metaphor for time management. Here’s how it works: if you don’t start with the most important projects in your day (the big rocks: work, family, health), something small (email, side projects, etc.) will take up that time or space. Therefore, it’s essential that you start with the big rocks.

I find this analogy works incredibly well when you’re writing your story.

The big rocks in your memoir are the key scenes that support your transformation. Why do we start with these “big rocks?” Because if you start with the pebbles (the stories that are interesting, but not pivotal to the story), it’s easy to get sidetracked.

I see this happen to too many folks when they start writing. It’s also a problem for those who like to work with writing prompts, especially while writing memoir. Although prompts can help, they can also lead to writing scenes or snippets that don’t belong in this particular story.

3. Flesh Out Your Narrative Arc

Once you’ve clarified your story’s scope, the pivotal transformation that occurred and the big rocks that you’ll use to tell your story, you’ll use that information to create a compelling narrative arc.

First, look at the big rocks you identified. How are they connected? Do they tell a clear story of transformation? We want to make sure that each big rock builds upon the last, adding complexity to your journey. If it doesn’t, revisit your list of big rocks. Is each one key to your transformation? If not, place it on a back-up list. Then identify what’s missing.

Although your story builds on one main conflict, additional challenges probably weave their way through the story. These will be your subplots or minor themes.

For example, my impetus for writing my grief memoir was to learn how to grieve consciously in a culture that barely acknowledges grief. At the same time, I was wrestling with the following:

I navigated grief as a member of the sandwich generation. I wanted to know how we raise children while burying our parents. How do we navigate those logistics? How do we fill our well when we’re caregiving on multiple levels?

Identity and ethnicity were important to me because a large part of my identity has always been my Serbian-American heritage. My parents immigrated from the former Yugoslavia, and we spent a good deal of my childhood going back and forth between Chicago and Yugoslavia. Since my husband is Japanese-American, I wanted to explore the cultural as well as familial patterns I was passing down to my children, as well as what I was ready to release.

Take a moment to clarify two or three minor themes that are starting to emerge in your memoir. Next to each, add a specific scene that exemplifies that theme.

For example, after my mother’s death, I ran into an acquaintance speaking German with her child at the grocery store. I made a passing remark about wishing I’d spoken more Serbian with my children when they were younger, which led to a cascade of regret around what I was (or wasn’t) passing down to my children. That was a very specific happening in a specific time and place (i.e.: scene) in which I was forced to grapple with my ethnicity. This is how you can fill out the narrative arc and build a rich, complex story.

4. Jump Into the Deep End

Now that we’ve got a list of your book’s most important scenes, where do you start? How do you open the book?

Start by jumping into the deep end. Don’t wade into your story.

In other words, start with your story’s inciting incident. What was the event that kicked off your crisis? Start there. And start with the raw, beating heart of it, not what happened the day before.

When we don’t know where to start, it’s easy to wade in with backstory: here’s what happened before this incredibly important thing happened. But that doesn’t pull your reader in. Nor does starting with the story of your birth.

What those beginnings do is ask your reader to wait—to be patient, to keep reading in hopes that something important will happen soon. But they might not wait for long. So indicate what’s at stake from the start. Later you can weave in the most important parts of your backstory.

Think about your experience listening to a master storyteller versus the friend who always bungles an anecdote. The master storyteller entices you with tension, making you wonder what will happen next, while the not-so-great-storyteller hems and haws, trying to get the story straight and figure out where to start.

Be that master storyteller. Know where your beats are, including where to start.

5. Recognize That Your Story Will Grow and Change

In all likelihood, the memoir you end up with will be different from the one you started with or envisioned. Early drafts are often for the writer. After all, we write what we need to know. Part of the memoir-writing process, then, is culling that initial material and shifting the focus to telling a great story. There’s a big difference between writing a book for ourselves and writing one for the reader, and we can’t always see see that distinction when we begin.

Knowing this from the start can help keep your expectations in check. It can also allow you to have some compassion for yourself throughout the process. At its heart, memoir is a process of discovery—for the writer as well as the reader.

And here’s the thing: just as your story grows and changes, so will you. The process of writing your memoir may expand the constraints of what you thought was possible for yourself. I’ve seen this with my clients, as well as experienced it myself. Whether or not you end up publishing your memoir, the very act of writing it allows you to move into a deeper, more authentic sense of self. And that is a powerful experience.

August 22, 2019

How to Get Out of the Writing Doldrums

Today’s guest post is by author, editor and writing coach Mathina Calliope (@MathinaCalliope).

No matter how much we love writing, sometimes we find ourselves in the doldrums: the blank page terrorizes us, we question our fitness for this life, others’ successes poke at our inner green monsters, and rejections demoralize us.

When this happens, how do we combat it? Probably too many of us turn to social media for a distraction, but when I do that, it does nothing to lift me out of the muck. Lately, I wondered what might be more fruitful, and I hit on the idea of writer candy—completely accessible, easy ways to nourish our muse and get us back to the page. They’re treats that don’t depend on factors outside our control such as an elusive rush of inspiration or energized productivity or on validation from gatekeepers.

I’ve been feeling discouraged since early spring. A handful of tough rejections have felt like indictments not only of my writing but, given that I write memoir and personal essay, also of me.

Such setbacks can get under our skin and pervade everything about our writer selves in ways both overt and subtle. Although my early summer was jam-packed with immersive, positive writerly experiences (Yale Writers’ Workshop, Denver’s LitFest, Barrelhouse’s Writer Camp), I couldn’t seem to shake the insecurity the rejections provoked.

So when I sat down to write out my intentions* (a fun dose of woo I highly recommend) for August, it surprised me that they all related to writing. Usually they’re spread across various domains of life: fitness, work, friendships, fun. But this month they were a monolith:

I honor my muse and creativity.

I write for the love of it.

My voice is true, powerful, and uplifting.

My writing reminds people of what really matters.

I have an agent.

I believe in my book.

* I state my intentions as positives in the present tense as if they’re already true—it’s a trick yoga teacher training taught me. Theoretically, this helps the Universe help me.

Intentions are funny things. Sometimes they manifest lickety split and sometimes they linger in my notebook and rattle around my brain for months or even years. Once I write them down I try to read them aloud once a day, and if I haven’t been making one of them happen, this can feel like a soft rebuke. That’s how #2 has been for me this month. I seem to have forgotten how to do it or what it even means.

It occurred to me that the way there might be through writer candy—easy-to-access and reliably pleasurable writing-related activities. So I came up with a list of them:

Prompts. They’re quick and low stakes, and they almost always yield something unexpected. Look for lists of prompts online, pick up the book 642 Things to Write About, or take Leslie Pietrzyk’s bitchin’ Right Brain Writing workshop.

Word lists. I’ve been keeping word lists in various notebooks for as long as I’ve been writing. Anytime I come across a word I want to learn or move from my receptive to my productive lexicon, I jot it down. Simply going back to these lists and reading them makes me happy.

Libraries. Just being in a library, I feel myself becoming a better writer. I browse new titles and nearly always come across a book I’ve been wanting to read. It’s invigorating.

Novels. Reading the novel you want to read, not the one you think you should read, just delving into it Netflix style, may be the lowest-hanging fruit there is for climbing our way back into the tree of writerly productivity because it drops us instantly and easily into the language and rhythm of story.

Snarky usage books. Okay, one snarky usage book: Dreyer’s E nglish by Benjamin Dreyer. This guy managed to subtweet The New Yorker in a book: “If you’re going to have a house style, try not to have one that’s visible from space.”

Thesauruses. The physical, hold-in-your-hands, made-of-paper kind. Just browse one! I especially like J.I. Rodale’s The Synonym Finder and the Oxford American Writer’s Thesaurus . It’s fun to pore over how words relate to each other and to fill your brain with exciting new possibilities for your own writing—for when you’re in the mood to write again. Add them to your word list!

Think of all this stuff as writer self-care, maybe even writer kale, not candy.

There are times for ruthless discipline in the writing life, but there are also times for knowing not to push ourselves. In those times, gobbling up writing sweets may be the best reminder of why we do this, the best way to renew and refresh until our muse returns.

I let myself indulge in them this summer, got back to submitting, and even landed an acceptance or two. More important, I wrote again for the love of it.

August 21, 2019

Copyediting Jobs: How to Estimate Hours and Pricing

Photo credit: wuestenigel on Flickr.com / CC BY 2.0

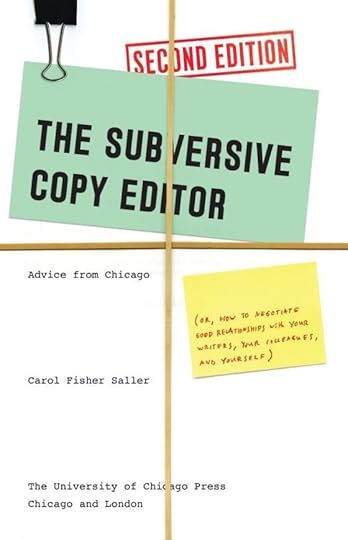

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from The Subversive Copy Editor: Advice from Chicago, Second Edition by Carol Saller (@SubvCopyEd), newly available as an audiobook.

In a blog post listing the best jobs for people with obsessive compulsive personality disorder, people with OCPD are described as “workaholics”:

People with OCPD prefer working in a highly controlled environment, with rigid adherence to rules and regulations without any exceptions. This makes them ideally suited for jobs that require perfection, conscientiousness, and attention to detail, but misfits for jobs that require spontaneity, imagination, flexibility, or teamwork.

Third on the list of jobs: copy editors.

Hmm. . . . really? Sometimes I wonder.

One freelancer I asked to do light editing returned a manuscript dripping with red, confessing that he “couldn’t help it.” The next time I hired him, he did it again. Both times, when sending his invoice, he mentioned that he had actually worked quite a few more hours than he was billing me for, and both times I felt that it was obvious why, so I didn’t encourage him to bill for the whole amount. Not only was it awkward wondering whether he felt I was taking advantage of him, but I noticed on the second project that while he had been fiddling with all that rewriting, he had actually missed a few typos and misspellings.

Another editor, a colleague, admitted to me that before she learned how to change all the underlining in a document to italics, she highlighted each one and changed it by hand. She knew it wasn’t necessary—that the typesetter would do it—but she did it anyway.

Copy editors have a propensity for meticulousness and perfectionism, traits that are important to us, and which in fact draw us to careers in editing in the first place. The problem is that there’s no end to the amount of fussing you can do with a document, whereas there’s a limit to the amount of money someone will pay you to do it. At some point it has to be good enough, and you have to stop.

Working to Rule

It’s common for an editing project to be assigned an estimated number of hours. At The University of Chicago Press, we have various formulas for estimating, but we’re aware that they’re rough guides. It’s difficult to guess what kinds of issues might slow the editing until we’re well into the work. Regardless, experienced editors know that there are two kinds of projects:

(1) the kind that deserves no more than the estimated number of hours, and

(2) the kind that takes however long it takes.

The problem is, how do you know which kind you’re doing, and if it’s type 1, how do you “work to rule”?

If you are a freelancer and you’re offered a flat fee for a project, you can assume that the estimated number of hours is what you’re expected to give it, and not much more. If you’re being paid by the hour, it’s usually easy enough to get a sense of a project’s importance by asking the assigning editor. (“If I find that it’s taking longer than estimated, is that okay?”) Not that you’ll get him to say that the job is low priority and the document doesn’t need to be perfect. Rather, he will stress its importance if it’s the kind of project that he’s willing to invest more resources in. He might admit that the estimate was a rough one. He will always want to know if you run into difficulties with a project, but in some instances he’ll be quicker to advise ignoring a time-consuming problem.

Working to a specified number of hours is a skill that develops with experience. When you start a project, divide the total number of estimated project hours by the number of working days before the deadline. This will tell you how many hours a day you are expected to put in. If you can’t manage that many hours per day, perhaps because you are dividing your days among multiple projects, let the assigning editor know right away that the schedule isn’t going to work for you. (And if you’re a newbie, be conservative in guessing how many hours you’ll last before falling face-first into the monitor—it might surprise you that few people can sit and edit eight hours a day.)

Next, figure out how many pages an hour you ought to be editing in order to finish in the specified number of hours. Here’s how to do it. Start with the number of estimated hours. If the estimate includes cleanup, subtract about 15 percent to get the number of hours for editing. (Subtracting 15 percent is the same as multiplying by .85, if that’s easier.) Next, divide the number of pages by the number of estimated project hours to see how many pages per hour you should be editing. You can then multiply the number of pages per hour by the number of hours per day to find out how many pages a day you should aim for.

Monitor your progress. After a few days, if you’re on or ahead of target, fine. But if you’re taking too long, make some adjustments. Figure out what’s slowing you down and how you can economize. You might decide to live with a style that isn’t perfectly in line with yours, if it’s logical and consistent. (This might involve undoing some editing you’ve already done.) If you’ve been straying from spell-checking into fact-checking, dial it back. Sometimes checking facts is part of the job, but often we do it merely because we can’t resist. Resist. If you’ve been writing long-winded queries or taking detailed style notes, try to labor less over them. If you’ve been going online to check the author’s citations or find missing information, stop doing her job. Query instead. Many editors take over authorial tasks to an unreasonable extent. When one of my colleagues finds a surfeit of mistakes in proofs and realizes that the author has done a slapdash job or not actually proofread at all, she tells herself, “You can’t care more about the book than the writer does,” and stops herself from reading the proofs herself.

Non-editing tasks can also be big time-suckers. If you’re juggling several projects at different stages of production, re-examine your habits and procedures to see where you can trim.

You might reasonably worry that making adjustments will entail lowering your standards. But let’s not be silly. Some of our “standards” are just time-consuming habits that don’t really make a difference to the reader. Letting go of them gives us time for more important tasks—and if working for our employers means working to a schedule, working for the reader means using the time we have in the best ways possible. So prepare yourself for the only extended use of italics for emphasis in this book: The document does not have to be perfect.

So how subversive is that? Not very. The document does not have to be perfect because perfect is rarely possible. There’s no Platonic ideal for that document, one “correct” way for it to turn out, one perfect version hidden in the block of marble that it’s your job to discover by endless chipping away. It simply has to be the best you can make it in the time you’re given, free of obvious gaffes, rid of every error you can spot, rendered consistent in every way that the reader needs in order to understand and appreciate, and as close to your chosen style as is practical.

Handling Stress Before It Escalates

If you’re freaking out over the amount of work you have or deadlines that are piling up or a temporary inability to concentrate because of distractions in your personal life, identify the problem and do something about it. If it’s a persistent problem, examine your habits and resolve to make some changes.

If it’s something more particular and immediate, you might have to ask for help in managing your work.

The solution might be to put in some extra hours. Or see a therapist, or get more sleep, or talk to a friend, or watch a funny movie. (My friend Sarah puts on the soundtrack of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.) The important thing is to find a way to shine some light on the end of the tunnel.

Have a Life

Have a LifePut briefly, the way to bring your best to any job is to have a life away from the job. If you bring your best to your work knowing that the manuscript is not your life, you’ll understand why one former colleague and mentor was not lowering her standards or abandoning responsibility when she used to counsel us: “Remember—it’s only a book.”

How deliciously subversive.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out The Subversive Copy Editor: Advice from Chicago, Second Edition by Carol Saller.

August 16, 2019

The Big Memoir Pitfall to Avoid

Photo credit: Sworldguy on VisualHunt / CC BY-NC-SA

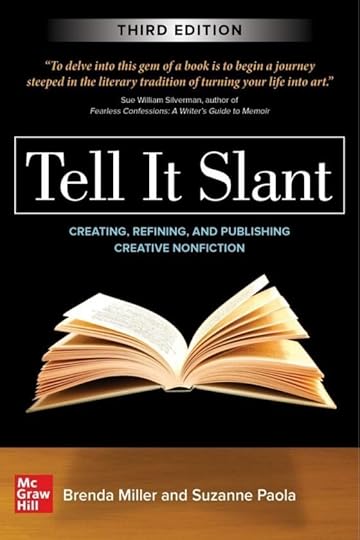

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from the new third edition of Tell It Slant: Creating, Refining, and Publishing Creative Nonfiction by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola.

Ironically, while creative nonfiction and memoir writing can be a tool of self-discovery, you must have some distance from the self to write effectively. You must know when you are ready to write about certain subjects and when you are not—when you are still sorting them out for yourself. Perhaps you will be able to write about a small aspect of a large experience, focusing your attention on a particular detail that leads to a larger metaphorical significance.

This is not to say that creative nonfiction or memoir is devoid of emotion; on the contrary, the most powerful nonfiction is propelled by a sense of urgency, the need to speak about events that touch us deeply, both in our personal history and those that occur in the world around us. The key to successfully writing about these events is perspective.

As readers, we rarely want to read an essay that smacks either of the discourse appropriate to the “therapist’s couch” or “revenge prose.” In both cases, the writer has not yet gained enough perspective for wisdom or literature to emerge from experience. The writer may still be weighed down by confusing emotions, or feelings of self-pity, and want only to share those emotions with the reader. In revenge prose, the writer’s intent seems to be to get back at someone else. The offender does not emerge as a fully developed character, but only as a flat, one-dimensional incarnation of awful deeds. In both cases, it is the writer who comes out looking bad.

The best writers also show a marked generosity toward the characters in their nonfiction, even those who appear unsympathetic or unredeemable. For example, Terry Tempest Williams, in “The Clan of One-Breasted Women,” writes an essay that is clearly fueled by anger, but it does not come across as personally vengeful or mean-spirited. Most of the women in her family died of cancer, an illness that could have been caused by the government’s testing of nuclear weapons in her home state. By channeling her energy into research, she shows herself as someone with important information to impart, aside from her own personal history. She creates a metaphor—the clan of one-breasted women—that elevates her own story into a communal one. By directing her attention to the literary design of her material, she is able to transcend the emotional minefield of that material. “Anger,” she has said, “must be channeled so that it becomes nourishing rather than toxic.”

The Warning Signs

In your own work, always be on the lookout for sections that seem too weighed down by the emotions from which they spring. Here are some warning signs.

Read the piece aloud and see if the prose has momentum. Where does it lag? Those are the sections that probably haven’t found the right details and scenes.

Seek out any sections that too directly explore your feelings about an event rather than the event itself. Where do you say words such as “I hated,” “I felt so depressed,” “I couldn’t stand”? The “I” here will become intrusive, a monologue of old grievances.

If you find yourself telling the reader how to feel, then you’re probably headed the wrong way. Channel your creative energy, instead, into constructing the scenes, images, and metaphors that will allow readers to have their own reactions.

On the page, your life is not just your life anymore. You must put your allegiance now into creating an artifact that will have meaning outside the self.

Useful Exercises

Try writing out a memory from the perspective of at least two people who were present (members of your family, perhaps). Get their memory down as accurately as you can by questioning them, and write it as carefully and lovingly as you write your own. Think of this as an exercise in the quirks of individual perspective. If you like the results of this exercise, try juxtaposing pieces of each narrative, alternating the voices, to create a braided essay.

Are you doing “the dodge”? Go through your drafts and identify those moments most difficult for you to write. Ask yourself simply: How clear is what is happening here? A series of “it was like” or similar type sentences built on metaphor always needs to be scrutinized, asking the question of whether or not the reader knows what exactly was like that. Likewise, search for broad-brush statements giving “that relationship was a nightmare” kinds of declarations. If you are dodging, write a clear paragraph describing that moment or event purely factually. At this point, decide what of this material you actually need to incorporate into your piece. Or consider other strategies like “breaking the fourth wall.” Let your readers tell you if that move works.

If you have no memory of a crucial event from a time period when your memories are otherwise clear and accessible, you may want to state this fact and probe why that might be the case. Your meditation on this trick of memory might tell us more about that time than the facts of the memory would.

If you have no memory of a crucial event from a time period when your memories are otherwise clear and accessible, you may want to state this fact and probe why that might be the case. Your meditation on this trick of memory might tell us more about that time than the facts of the memory would.Comb through the piece you’re writing to ferret out any hint of therapist’s couch or revenge prose. See if you can replace these moments with concrete details or images instead.

Note from Jane: if you enjoyed this article, be sure to take a look at the new third edition of Tell It Slant: Creating, Refining, and Publishing Creative Nonfiction by Brenda Miller and Suzanne Paola.

August 8, 2019

How to Establish a Long-Term Writing Career: Insight From Two Literary Agents

Today’s guest post is a Q&A by Sangeeta Mehta (@sangeeta_editor), a former acquiring editor of children’s books at Little, Brown and Simon & Schuster, who runs her own editorial services company.

For novelists and nonfiction writers seeking traditional publication, landing a book deal is the dream. And if that deal receives publicity—perhaps due to a multi-publisher auction—then there’s even more reason for the writer to feel like they’ve “made it.”

Some writers will be content with that first deal and have no desire to publish more books. But what about the writers who hope it will be followed by many more—the ones who aspire to make money from their writing, or build a career out of it? How can writers endure in a field that’s known for its instability?

Inspired in part by Cynthia Leitich Smith’s “Survivors” series on how to thrive as a longtime, actively publishing author, I spoke to literary agents Sarah LaPolla and Kim Lionetti about strategies for building a long-term writing career. As with all my Q&As, neither agent knew the other’s identity until after they submitted their answers.

Sangeeta Mehta: So many writers dream of receiving a large advance with a book deal. The assumption is that, the bigger the advance, the more money the publisher is likely to put into marketing their book so as to guarantee robust sales. Is there any truth to this thinking, or is there an advantage to receiving a small advance?

Sarah LaPolla: Like with many things in publishing, the answer is “yes and no.” Big advances can be great. They’re the goal for many writers and agents alike. Big advances can be a sign a publisher is investing heavily in a certain author or book, and by doing that they’re also taking a risk. So, it does often mean they will put more into marketing and publicity than they do for other books to ensure they get a significant return on that investment. Sometimes that ideal scenario does happen and everyone involved wins!

That said, it isn’t always the case. Maybe that big-advance book doesn’t get as many pre-sales as the publisher wanted, or gets mediocre reviews, or underperforms in its first quarter. A publisher at that point might re-strategize, or they might cut their losses, and the author ends up never earning out that big advance. That can hurt in the long-term. When it comes time to sell the next book, a publisher may use those figures against them by offering a lower advance or passing entirely. Publishers want to see that an author will make them money, and that’s done by earning out advances and earning royalties. A smaller advance might not be as exciting, but it can mean an author has a better chance of earning out, proving their monetary worth to the publisher, and potentially having a longer career overall.

Kim Lionetti: There’s certainly some truth to that. If a house has made a substantial investment in the author, then they’ll want to do what they can to build his/her career. That said, a big marketing budget doesn’t guarantee the publisher will earn their money back. Sales aren’t predictable. And if the publisher ends up losing a lot of money on that first book, it will make their support of future books harder.

There are still plenty of opportunities for authors on a smaller level. Depending on the publisher’s budget, the house might want to keep the advance lower to give the author an opportunity to earn out and also apply some of those funds to marketing. The biggest advantage to a smaller advance is that it’s easier to earn out. If your first book/contract earns out, that gives you a much better chance at a second contract.

For a debut author, what’s more important—that their book is well reviewed and nominated for awards, or that it exceeds sales expectations? Does critical success sometimes increase the writer’s chances of being offered a second book deal more than commercial success, because the writer is seen as “up-and-coming”?

SL: This is dependent on what’s more important to the author as an individual and what makes the most sense for the types of book they write. Commercial success is often a driving factor because publishing is a business and we all need to make sure a book will sell as many copies as possible. There are always critical darlings that end up being cult favorites or were never really written with a mass audience in mind in the first place: “quiet” literary novels, experimental fiction, and niche nonfiction, for example. The publishers of those books will have different expectations when it comes to what makes them “commercial” hits, and in those cases critical success will likely play a larger role in what’s considered more important.

KL: Sales track records are pretty important. The book doesn’t necessarily need to have been a huge financial success, but if it had really disappointing sales, that will create an uphill climb for the author going forward. If the book had great reviews, that will certainly help make a case for another deal, and this is when an agent can make a big difference. Part of our job is to find ways to give your career longevity, whether that means “rebranding” or just coming up with ways to pitch you that can overcome a disappointing track record.

Publishing is a business, first and foremost, so commercial success will always be valued. But if you’re not quite there yet, editor and house enthusiasm for you and your work is a huge factor. If they love your work, love working with you, and you’ve received critical acclaim, then they’ll want to stick with you and try to build your career.

Many writers also dream of landing their first book deal at an early age—of declaring themselves published writers without having to associate themselves with any other profession. Do these writers have an edge in that they have more time to find their voice and settle into their careers? Or does it not matter when a writer is first published, so long as they dedicate themselves to writing from this point on?

SL: Sometimes I see writers as young as 14, 18, 22 post about needing to be published already or considering themselves a failure if they didn’t get an agent before they turned 25. There’s no way to convince a young person how young they are, but hopefully there’s a way to put career longevity into perspective. The truth is, not many authors get the chance to grow with their career over time. If the first few books don’t do well, or are perceived as mediocre on a writing level, it makes it harder to convince publishers to keep giving you chances.

Most people don’t find their voice until later in life, and a good author—someone who sees writing as a career and approaches it professionally—should get better with each new book. That means they keep reading, learning, and challenging themselves. Sometimes I love working with younger writers because they’re so eager to learn. Older authors may have more experience and may even be stronger writers, but sometimes they’re less willing to accept criticism. There’s no magic age to becoming a published author. There are going to be pros and cons to everything. What matters more is whether that author waited until their work was ready to share, and whether they will be dedicated to keep growing their career going forward.

KL: Only a very few can count themselves as full-time writers. Most have day jobs and squeeze in writing whenever they can. It doesn’t matter at what age a writer is first published, and it doesn’t matter if they have to keep another job to pay the bills, they just need to find the time to get their stories on the page. Easier said than done, I know, but I think becoming a professional author takes a special kind of drive. If you have that kind of motivation, you can make it happen at any stage of life.

Writing a second book is notoriously challenging for almost any author. In your experience, is “second book syndrome” more common among writers trying to replicate the success of their first book, or those who consider their second book a second chance to prove themselves? How do you encourage writers who fall into either camp?

SL: This is, sadly, not a myth. The second book is the hardest. (Though I’m not sure if any writer would say any book is easy!) Part of this is because a writer may have written Book 1 over the course of 10 years, spent another few months finding an agent, another year working on edits and trying to sell the book. Book 2, meanwhile, is on a deadline. It’s either already under contract with a deadline of less than a year—as opposed to the accumulated decade of planning and drafting that Book 1 got to enjoy. Or the publisher is asking what’s next. Book 1 was successful and now they want more. That’s where the pressure of replicating that success comes in.

I also try to remind writers that they are in a different place with Book 2 than they were with Book 1. They have a support system now, they’ve been through the editorial process before, they know what to expect and where to find help if they need it. I tell my authors to start working on Book 2 while Book 1 is on submission. It’s not only a distraction from submission, but it also provides a framework for when Book 2 comes next. That doesn’t always make the writing process itself easier, but I always go back to what I tell my own authors in these situations: You Got This.

KL: Many authors spend more than a year on their first books. They’ve had many pairs of eyes on it, from the time they had critique partners reading it, to their agent and then their editor giving them notes. It was workshopped several times over. The second book usually needs to happen more quickly, so that the author can start building a readership after that first book is published. I think a lot of the issue is “letting go” of that first book that you spent so much time honing, and fear that you won’t be able to replicate that magic. Authors should lean on their agents for brainstorming, and talk through plot points. I think the key to getting past the “second book syndrome” is to find your way to an idea that you can get as excited about as you did with that first book. Making it a collaborative effort is a great way to do that.

How important are fallow periods in a writing career? Do they tend to inspire creativity—or cause the writer to lose momentum? If a writer takes too long of a break in between books, does this make it harder for them to secure new publishing deals, or is this entirely dependent on how their previous book was received?

SL: No author is a machine, despite how those “one book a year” authors make it look! Taking breaks is essential to fostering and protecting creativity. Losing momentum is entirely up to the author, and I hope they’d maintain a support system that keeps them motivated. That’s not always the case. I think a lot of getting back into a publishing career can depend on how their previous books were received.

We hear of writers all the time who release their first novel in 10 years to wide anticipation, or of readers anxiously waiting for the next novel in a series. Building a strong fanbase early in your career often means those fans will be there waiting for you. For writers who haven’t built those devoted fanbases yet, taking a long time between books can make it a little harder to secure a new deal. That author (and their agent) may need to approach a new deal like a debut novel again, which can be an exciting way to re-launch a career, but also feel like you’re starting over.

KL: I recommend to my clients that they always be thinking about their next project. I’m sure there are exceptions, but I think it’s easy to get stuck in a break and never come out of it. And yes, if you’re trying to build a fanbase, it’s difficult to do that if you have long stretches between books. Readers will forget about you and stop following your career.

Honestly, I’m not an expert on the creative process. Perhaps some authors do benefit from the breaks. But from the standpoint of someone trying to help build your brand, I think it certainly makes things more challenging.

If an author is very established in a certain category or genre but is eager to try something new—say switch from adult books to children’s books or from historical fiction to commercial fiction—would you encourage them to experiment, perhaps with a pen name? Or is it in their best interest to keep building their brand?

SL: I think it’s very common for an author to eventually want to try a new genre. If they are very established in the sense that they are a household name, then a publisher may want to capitalize on that name regardless of what they write. I don’t think a pen name is necessary if the switch isn’t drastic. For example, writing picture books and writing erotica under the same name might not go over well with readers or publishers. Writing YA fiction and adult mainstream fiction, however, wouldn’t require a pen name but the author can still opt to keep those careers separate if they choose.

KL: There are so many variables that come into play here. Do the genres have a crossover audience? How successful/established are you in that first category? How fast do you write? Could you maintain a momentum in the category you’re already known for, while you make a foray into this new genre?

If you’re doing well in a certain genre, then it certainly behooves you to keep writing to that audience and continue building that brand. But if you can write quickly enough to also experiment in other genres, then all the better. The use of a pen name, etc. would depend on those other factors. Is your name big enough to bring a crossover audience to these other books? Is there just a natural crossover appeal in the types of books you’re writing? There are many things to consider.

On the flip side, if you have an author who has made a name for him or herself in a genre that is losing steam, would you advise them to give another genre a try, even if they would rather continue on the same path? Aside from major bestselling authors, do you think every writer must reinvent themselves sometime in their career?

SL: Being able to change as the market changes is an important part of maintaining a publishing career. Genres get trendy and then cool down all the time. If a writer establishes themselves in one genre, they might not feel the effects of a downward trend the way writers new to the genre will. But the industry itself changes all the time—publishers merge, marketing budgets shrink, books are produced in new ways, authors find income from different sources, etc. Everyone involved needs to diversify in order to survive in this industry, and for individual authors who may find their genre of choice is no longer selling well, that could mean finding a new one.

KL: I do think authors need to be open-minded and flexible. “Reinvention” sounds drastic and something like that isn’t always necessary, but often there are ways to tweak the books you’re writing to allow agents to pitch them in different ways. Part of my job is to recognize your strengths and how they could be used in a way that’s currently marketable to publishers.

A lot of the trends are cyclical. Even if the genre you’ve been writing is going through a rough patch, you may very well see it come back around again in a few years. In the meantime, though, you might need to explore other options.

If you had to name one quality that’s essential for writers looking to play the long game, what would it be? Drive? Flexibility? Optimism? Confidence? Do you have any other advice on how writers can embrace the inevitable twists and turns of our industry?

SL: Patience is the most important quality to maintain in publishing. I think with patience comes flexibility and optimism, and those would be my other choices if I were allowed to name more than one quality! My biggest advice to writers is to focus on what you can control—writing, making connections in your local literary communities—and not harbor resentment or anxiety over the things you can’t. Always look to what happens next, and not what didn’t happen before.

KL: Resilience. Honestly, I think that quality encompasses all of the words you used above and more. This industry can be quite humbling along the way. The most successful authors, with the longest careers, use those challenges/setbacks as fuel to keep pushing for the next level of success. They learn from them and just keep moving forward with a positive attitude.

There’s been a ton of change in this industry since I first started working in it 25 years ago. When the shake-ups happen, it always feels a bit scary at first, but results in some pretty exciting, innovative stuff. Publishers are thinking outside of the box now more than ever, and that brings more opportunities to all of us.

Sarah LaPolla (@sarahlapolla) has been an agent at Bradford Literary Agency since 2013. She started her career working in the foreign rights department at Curtis Brown, Ltd. in 2008, the same year she received her MFA in Creative Writing from The New School. Sarah primarily represents Middle Grade and Young Adult fiction in a variety of genres, as well as select Adult fiction. Regardless of age demographic or genre, Sarah would like to see more hope and humor even in the darkest of stories. She is especially interested in diverse casts of characters and in authors who shine a light on voices that have been historically underrepresented. Sarah’s authors tend to reflect larger themes within a character-focused story that, whether overtly or subtly, challenge the status quo. Find out more.

Kim Lionetti (@BookEndsKim) is Senior Literary Agent at BookEnds Literary Agency. Having started her twenty-five-year career in the industry as an editor at Berkley Publishing, Kim enjoys helping authors shape their works into books their readers will love. She works with bestsellers and award winners in a variety of genres, including women’s fiction, romance, suspense, and young adult. She’s eager to add more diverse voices to her list, and as an autism mom, she’s most passionate about stories featuring neurodiverse characters, and those with special needs. Learn more.

August 2, 2019

Before You Market Your Book, Set Your Objectives

Photo credit: thumeco on Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-ND

Today’s guest post is an excerpt from One Million Readers: The Definitive Guide to a Nonfiction Book Marketing Strategy that Saves Time, Money, and Sells More Books by author and nonfiction writing coach Boni Wagner-Stafford (@bclearwriting).

The very first thing you want to nail are the marketing objectives for your book. You’re likely familiar with objectives and the key role they play in any business (or personal) endeavour.

The many authors that discount, overlook, or dismiss setting objectives for their books as irrelevant miss out on the key strategic link that objectives provide between dreams and reality.

What Are Objectives?

The objectives are the pillars for everything you plan and do related to the marketing of your book. It’s your why, your goals, your dreams, all wrapped up into an action-focused package.

Objectives describe exactly what you want to achieve through your marketing approach. Here’s an example using a special vacation as an analogy.

Your objective for the vacation might be to unwind, relax, and recharge your batteries. Or, it might be to experience a thrilling physical adventure, such as climbing Mount Everest, rowing across the Atlantic, or some other experience where you’ll push yourself beyond your current boundaries.

Understanding your objectives for your vacation will help you:

Choose the location. A five-star beach resort will be perfect for the relaxation objective but not so much for the adventure.

Decide how you’ll get there. A direct flight, perhaps in first class, will be perfect for the relaxing beach vacation. Backpacking, hitchhiking, or train might allow you to experience more of the region you’re visiting for your adventure vacation.

How much money you’ll spend in order to meet your vacation objectives.

It’s the same thing with the objectives for your book marketing strategy.

Why Determine Objectives Before You Begin

Ideally you will have examined your objectives for the book early in the writing process, as objectives will affect everything including your content, tone, design, and length.

Your objectives are going to help you decide everything you do to market your book and yourself as an author. They will be objectives unique to you and your book.

How to Set Objectives

How do you figure out what your marketing objectives are? It might be easy. You might know them without doing any work at all. If you don’t know them, or even if you think you do, think hard and dig deep so that you can get specific.

In general, the objectives of most authors will fall into these three broad categories: awareness, engagement, and book sales. Start by drilling down into each of these categories.

Here’s what you need to ask:

Awareness

What kind of awareness do you want to raise? Is it for you as an author? For your book, or for the subject you’re writing about? All of the above?

Who is it that needs to be more aware?

Is this awareness a prerequisite to some change you’re advocating?

Engagement

Do you want to speak at conferences and events?

Do you want to engage with readers by doing book readings or signings?

Do you want to speak at schools, libraries, or business meetings?

Do you want to build an online community of loyal readers, or build an engaged email list of readers who will want to buy your next book, and the one after that?

Book sales

How many books do you want to sell? Be realistic and also bold in your answer to this one. Don’t say two, but also probably don’t say two million.

How do you know what’s a realistic goal? It depends on the genre; it depends on the marketing strategy; it depends on the quality; it depends on your marketing budget; and it depends on whether you have a team or you’re marketing solo.

Research how other books are selling in your genre. Use tools like KDP Rocket, or KDSpy, or even start with a simple Google search. My search using the term, “global book sales by genre,” led me to statistics where, for example, I re-discovered that more money is spent buying business books than all fiction categories combined.

You can also do some manual searching on Amazon, though both KDP Rocket and KDSpy source Amazon data, so if you have access to those tools then your job is a little easier. Get a good sense of what the bestsellers in your genre are doing, be realistic about your chances, and set yourself a stretch goal. Make it something that’s going to make you proud once you’ve achieved it.

Here are two quick examples. Sheila has written a book about her business. Joe has written a memoir about his family’s story. Their marketing objectives are going to be different, even though they will each have objectives in the broad categories of awareness, engagement, and book sales.

If you fail to nail your objectives before you begin to work on the rest of your book marketing plan, you risk including too many irrelevant tactics or not enough of the right ones. And you will have a harder time achieving the objectives you set.

General Versus Specific

At Ingenium Books, crafting marketing strategies on behalf of authors is a collaborative effort. We ask authors to complete a series of questionnaires and we have one or more conversations to get them thinking and to be sure we can extract and articulate clear and authentic objectives.

In this collaborative process, however, most authors do not show up with the level of specificity we want them to reach for, in particular around the objectives. Broad objectives are better than no objectives, but specific objectives are far better than broad objectives.

Why Awareness Always Comes First

Let’s say, for example, that an author’s stated objective at the start of our process is to get hired for speaking engagements. In this case, an author may say they don’t really care about becoming well known and they don’t care that much about book sales.

What has to be in place before they receive offers to speak at conferences and events? The person making the offer must be aware that the author and the book exist. Therefore, awareness must come first. No one will hire an author they don’t know about.

We could leave this author’s marketing strategy with those two objectives: raise awareness and get hired for speaking gigs. However, book sales play a key role.

Getting hired for speaking gigs—the author’s number one objective—requires awareness on the front end and book sales for credibility on the back end. It’s great if Sam the Conference Organizer finds out there’s an author who has written a book about the specific topic the conference wants to address. It’s better, by far, if there is evidence that people are actually buying the author’s book. If there’s demand for the book, Sam knows there will be an engaged and interested audience at his conference.

Getting hired for speaking gigs—the author’s number one objective—requires awareness on the front end and book sales for credibility on the back end. It’s great if Sam the Conference Organizer finds out there’s an author who has written a book about the specific topic the conference wants to address. It’s better, by far, if there is evidence that people are actually buying the author’s book. If there’s demand for the book, Sam knows there will be an engaged and interested audience at his conference.

It’s this third pillar, book sales, that is the most common objective for most authors. Including tactics in your marketing strategy around awareness is critical for achieving book sales: readers are less likely to buy a book from an author they’ve never heard about.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, check out One Million Readers: The Definitive Guide to a Nonfiction Book Marketing Strategy that Saves Time, Money, and Sells More Books by Boni Wagner-Stafford.

August 1, 2019

Masterful Wordsmithing with Metaphor and Imagery

Today’s guest post is by author and editor C. S. Lakin (@cslakin).

Metaphors, similes, and creative imagery can be useful, creative tools for relaying emotion. In case you don’t remember, a metaphor, according to Reedsy, is “a literary device that imaginatively draws a comparison between two unlike things. It does this by stating that Thing A is Thing B.” A simile compares things, usually with as or like.